Research Article

Research Article

Weaving Tradition: The Ancient Art of Dhabhla in Kutch

Arooshi1 and Dr. Neeraj Rawat Sharma2*

1Research Scholar, Design Department, Bansathali Vidyapith, Rajasthan

2Assistant Professor, Design Department, Bansathali Vidyapith, Rajasthan

Dr. Neeraj Rawat Sharma, Assistant Professor, Design Department, Bansathali Vidyapith, Rajasthan.

Received Date:February 04, 2025; Published Date:February 18, 2025

Abstract

The Kutch, the desert area of India is the origin of an elegant weaving technique known as the Dhabhla. Traditional Dhabhla art has advanced throughout time because of cultural influences and generations. The Dhabhla cloth was primarily produced by the people of the Vankar community mostly found in the Kutch region of Gujarat. In the presented work, efforts have been made to properly document the journey of the Dhabhla weaving from its origin to its current status. The study integrates several literature sources such as books, articles, museums etc. for proper information about the history of the craft. In the later stage of the article, various visits were made to the different exhibition centers in the Kutch region, and interviews with craft persons from different villages were conducted to determine the current status of the craft, designs, tools, techniques and the profile of the artisans were documented in detail.

Keywords:Traditional; Vankar; Techniques Dhabhla

Introduction

India is well known as a textile-rich country. The handlooms have impressed a distinct status for themselves. The practice of weaving by hand is a part of the country’s social ethos. Handlooms, also being supported by royalty, have also been woven for the common people. They have been significant items of trade. People have specialized in various techniques and designs for periods and pass on their skills to the next generation. An exclusivity of traditional Handloom is found not only in colors and designs but also in qualitative raw materials and techniques to produce it [1].

Gujarat is known for its rich textile tradition and handloom weaving has played an Important role in the state cultural and economic landscape for centuries. Gujarat handloom textiles are famous for their intricate designs, vibrant colors, and craftmanship. Some key aspects of Gujarat handloom-Patola (single and double ikat silk), Khadi (hand spun &handwoven) and Mashru (a blend of silk and cotton) (Figure 1).

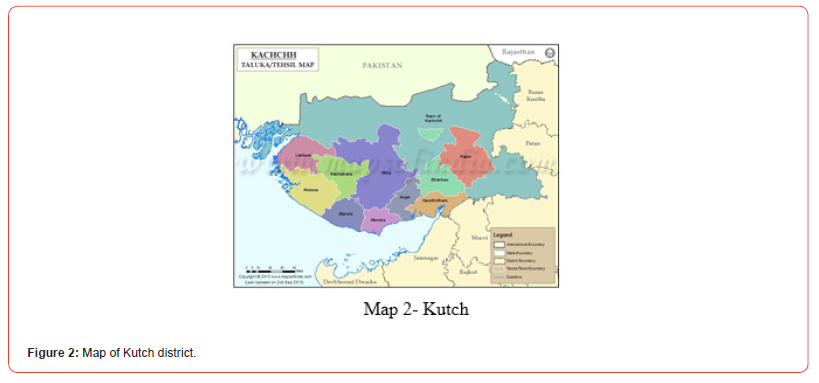

Kutch, often referred to as Kachchh is a district located in the westernmost part of the Indian state of Gujarat. It is the largest district in Gujarat and shares its borders with Pakistan to the west. Kutch is very dry, besides environmentally dissimilar from the rest of the country as most of its area is covered with salt desert ecosystems. The shallow soils of Kutch with the dry climate allow indigenous grasses to flourish, creating pastoralism as a good method to yield food. The Rann of Kutch, a wildlife sanctuary and a seasonal salt marsh are the two prominent geographical features of the region. In the Kutch area of Gujarat, there is sufficient access to sheep wool from the local Rabaris community (Figure 2).

Indian handloom and handicraft articles have been extremely famous all over the creation for centuries. They have formed their particular place in customers’ observations and preferences. Gujarat has its share in the handicraft market of the country. Among various crafts of Gujarat, Dhabhla is a type of handloom shawl, blanket or wrap woven by the artisans of Kutch for generations. It is traditionally worn by the people of Kutch as a part of their everyday attire. The preservation of this age-old bond between humankind and nature is further enhanced with the identification and use of pigments and natural dyes, which now help in the enhancement and revival of the traditional craft. As per the literature, Dhabhla weaving started in Kutch when the Vankar section of the Meghwal community migrated from the neighboring state of Rajasthan to the Kutch region of Kutch. The Vankar community were traditionally the weaver’s community, but the locals in Kutch needed to gain weaving skills. To fulfil the needs of both communities, the association between the Vankar and Rabaris community members grew with time. The former would weave shawls using the locally available resources, and the latter would use them during the cold winter months. The resultant craft became known as Dhabhla weaving, now famous worldwide for its natural colors and traditional weaving technique. Dhabhla is a big handy shawl that can be used as rain cover during monsoons, as a rug to sit on, wind-cheater and as a quilt during the night. It is vibrant in colour and adorned with extra weft motifs in different shades and hues. However, the main occupation of various ethnic groups of Kutch is agriculture and raising animals. Tribes started and survived their traditions, customs and rituals. With time, many of the Vankar and Rabaris communities have become full-time weavers. ‘Vankar’ is the widespread identity term used by a 2-3 decades old community to state themselves [2-5].

The maintenance of the age-old bond between humankind and nature is further enhanced with the identification and use of pigments and natural dyes, which now help to enhance and revive the traditional craft. Natural colors were used to produce the traditional Dhabhla, 100 inches in length. Traditional Dhabhla blankets were weighed between 2.5 Kg and 3 kg, made using thick wool, and of size 4.5ft x 8ft to wrap the body by the Rabaris. The Rabaris also used the Dhabhla cloth for sleeping while travelling through the forests. The Rabaris women would meticulously weave a Dhabhla- a conventional blanket worn by the males of the hamlet. The Dhabhla was historically constructed of single and two-ply wool and was rather heavy. Due to its delicate patterning, raindrops could not penetrate the cloth. Males also wore the Dhabhla to keep them comfortable throughout the day [6,7].

(Times of India, 2012), Story linked to the origins of this craft tells of ‘Ramdev Pir,’ who once visited Narayan Sarovar during his journey. His followers built a temple in his honor and asked him to bring his family from Rajasthan to help manage it. This migration led to the establishment of shawl weaving in Kutch.

(Chaand, Yadav, Sachan, N Tewari, 2011), “The main motifs of Dhabhla craft comprise jaad, lath, satkhadi, and chaumukh. Tiny dots encircling the satkhadi motif, with a diamond shape at its center, represent the essence of traditional Dhabhla weaving.”

This study sought to investigate the traditional Dhabhla craft of Gujarat and the innovative approaches for its revival. It concentrated on documenting the distinct features of Kutch’s Dhabhla art, including its techniques, materials, tools, raw resources, and surface embellishment methods. The research also assessed the current status of handloom production. Another important goal was to analyze the socioeconomic profiles of the artisans involved in this traditional craft [8,9].

Methodology

To achieve the objectives of the study, a descriptive research approach was designed. The initial step involved gathering data from a range of primary and secondary sources. Field visits were conducted in selected areas of the Kutch district to collect primary data, focusing on obtaining firsthand information about the manufacturing process and other aspects of the craft. For secondary data, various university libraries and museums were visited, and information was also obtained from individuals knowledgeable about the craft.

In line with the research strategy, a comprehensive study of the socio-economic profiles of artisans involved in Dhabhla weaving was conducted, along with the documentation of the Dhabhla craft itself. Data collection utilized various methods, including focused personal and telephone interviews, field visits, informal discussions, and direct observations. To meet the study’s objectives, a structured interview schedule was developed, featuring a questionnaire with both closed-ended and open-ended questions to gather in-depth information [10].

The research focused on six villages in the Kutch district- Bhuj, Mandvi, Anjara, Mindro, Nirona, and Tukma. Using purposive sampling, 50 artisans were selected, from which detailed case studies were conducted with five Dhabhla artisans. The selection criteria emphasized artisans with a traditional family history in Dhabhla craft who are currently active in the field. Data was gathered through the structured interview schedule, informal discussions, and observations of the selected 50 Dhabhla workers, including the five case study participants. Documentation of the craft was enhanced with photographic evidence.

All discussions, meetings, and interactions took place in the local language, with responses documented in English. Secondary data was collected from various academic institution libraries, as well as from design and research organizations, museums, exhibitions, and trade fairs. The data was analyzed systematically, and the findings were presented in tables to provide a comprehensive overview of the craftsmen’s socio-economic backgrounds, living conditions, health status, job allocation patterns, sources of raw materials, production processes, challenges at each stage of production, trade terms, working conditions, market dynamics, existing technologies, designs and colors used, the role of developmental agencies, current infrastructure, legislation, social security coverage, critical issues affecting the traditional Dhabhla craft, and awareness of ongoing development programs and policies [11-13].

Results and Discussion

The data collected from various primary and secondary sources has been compiled, and the findings are presented below:

Documentation

Dhabhla, the graceful weaving of the deserts, has its origins in the Kutch area of Gujarat, India. The Rabari women would meticulously weave a Dhabhla- a conventional blanket worn by the males of the hamlet- until it was finished. The Dhabhla was historically constructed of single and two-ply wool and was rather heavy. Due to its delicate patterning, raindrops could not penetrate the cloth. Males also wore the Dhabhla to keep them comfortable throughout the day. The Dhabhla cloth is produced by the Vankar people in the Indian state of Gujarat. On the other hand, the Ahir population does not weave and primarily relies on agriculture and livestock. Despite their modest population, the Meghwal’s or Vankar are well-known for their bhojsari embroidery design. The Meghwal people are responsible for creating kashida pattu and Baladi checks.

The occupational structure of Dhabhla Weavers, a traditional craft, within a specific community context. Traditionally Meghwal community-Dhabhla making is described as intrinsically a craft of the Meghwal in the community being studied. This suggests that it has deep roots within Meghwal culture and history. Education and Entrepreneurial Traits: Meghwal Community involved in Dhabhla making tend to have higher levels of education and possess progressive entrepreneurial traits. This may indicate that they viewable Weaving making as a business opportunity and are self-employed in this trade. For Meghwal Community families involved in Dhabhla making, it is their main source of income. This implies a deeper reliance on the craft within Meghwal households, possibly due to historical or economic factors. Varying Employment Status: Meghwal’s Family engaged in Dhabhla making have varying employment statuses, indicating a range of involvement and dependence on this craft for livelihood among different households.

The findings indicated that the income generated by artisans from Dhabhla weaving is not sustainable, as it must be shared among a large family. These factors have led many artisans to pursue alternative income-generating activities that can provide them with higher earnings [14].

Origin and history of Dhabhla weaving

Based on discussions with senior Vankars and available

records, a timeline of change and transformation among the Vankar

community is outlined below:

500-600 years ago: The Meghwal community from Rajasthan

drifted to Kutch. The Vankars in Kutch are primarily Marwadas from

this traditionally oppressed community, which was historically

regarded as “untouchable.” These Marwadas who were landless

cohabited with the local pastoral Rabari community and other

groups such as Darbars, Ahirs, and Patels, forming hereditary

commercial relationships.

19th century to post-independence: This period saw weavers heavily impacted by the introduction of inexpensive mill-made textiles. As hand-spun yarn and employment opportunities declined, poverty increased. The interdependence among the aforementioned communities weakened as the country modernized. With the local market deteriorating, weavers began serving more customers from urban region and experimented with diverse raw materials and techniques.

1935 onwards: The Mahatma Gandhi introduced Khadi during his 1925 visit, marked current era. It was also a time of co-operatives, or Vankar Mandalis, aimed at protecting the economic, social, and cultural interests of the community. The first Khadi organization, Charkha Madhi, was established in Gadhshisha around 1940.

1947: Approximately 5,000 to 5,500 weavers gathered for a Weavers Sammelan in the presence of Shri Ravishankar Maharaj, a prominent Gandhian, to discuss pressing issues, particularly the shortage of yarn.

1959: The introduction of the fly shuttle enabled the weaving of wider fabric, which increased production capacity.

Pre- and post-1960: Previously, Marwada weavers primarily catered to local communities. However, in the 1960s, many Marwada families transitioned to other professions and moved to different villages. The establishment of Kandla SEZ marked a significant infrastructural development during this time.

Raw material and process of Dhabhla weaving

An outline of the raw materials and the process involved in

making a Dhabhla:

A. Raw Materials:

Cotton or Sheep Wool Yarn (desi oon): Traditionally, Dhabhla

are woven using either cotton, Goat or wool yarn. Desi wool is a

kind of wool produced by native sheep in Kutch. The choice of

yarn depends on factors such as climate, personal preference, and

cultural traditions. Traditionally to the Rabaris, they would collect

wool from the local sheep twice a year: first before the rainy season

and again near the conclusion of the winter season Cotton yarn is

lighter and suitable for warmer climates, while wool yarn provides

warmth and is preferred in colder regions.

Natural dyes: Artisans may use natural dyes derived from

plants, minerals, or insects to add color to the yarn. Natural dyes

can create a range of hues, including earthy tones and vibrant

shades, contributing to the aesthetic appeal of the Fabric. Allnatural

ingredients, such as onion scraps, lac, and madder, are used

in the dyeing process of vegetable colors. Dyed wool has seen an

uptick in popularity in recent years due to the growing popularity

of colored fabrics.

B. Process:

Yarn preparation: The first step in making a Dhabhla involves

preparing the yarn. If natural dyes are used, the yarn may be dyed

in batches to achieve the desired colors. Once dyed, the yarn is

typically dried thoroughly before it is ready for weaving.

Setting up the loom: Dhabhla are woven on traditional pit

looms, which are set up either in the artisan’s home or in small

workshops. The loom consists of a frame with horizontal and

vertical threads, known as the warp and weft, respectively. The

warp threads are attached to the loom and tretched tightly to create

a base for weaving.

Weaving: The weaving process begins by interlacing the weft

yarn through the warp threads using a shuttle. Depending on

the design of the shawl, the artisan may employ various weaving

techniques, such as plain weave or intricate patterns like stripes,

checks, or geometric motifs. This step requires skill and precision to

ensure that the patterns are evenly woven, and the edges are neat.

Finishing: Once the weaving is complete, the Dhabhla

undergoes several finishing processes to enhance its appearance

and durability. This may include trimming any loose threads,

washing the shawl to remove any excess dye or dirt, and pressing it

to give it a smooth finish.

Embellishments (optional): Some Dhabhla may feature

additional embellishments such as tassels, embroidery, or mirror

work, which are added by hand after the weaving process. These

embellishments can add texture and decorative elements to the

shawl, making it more visually appealing.

The findings regarding the designs and colors of Dhabhla weaving indicated that most production is now driven by incoming orders, making it difficult to identify specific reasons for the choice of colors or designs. While Dhabhla makers have taken steps to address health hazards associated with fabric production, only a small number of artisans have implemented effluent treatment measures, which have become a significant source of water pollution. Many artisans have participated in programs initiated by developmental agencies and have benefited from these efforts. However, the majority are seeking genuine external institutional support, particularly in marketing, to enhance their current conditions (Figure 3 & 4).

Feedback from the selected sample highlighted several urgent needs, including a greater focus on the quality of raw materials and finished products, further exploration of design possibilities, and the development of versatile products. Additionally, there is a need for initiatives aimed at upgrading the skills of the craftsmen. The current situation is one of responding to local market needs. It has become more common for the Vankar of Kutch to create textiles for the urban market in more significant numbers than ever before. This strategy is used throughout the weaving process because of its adaptability. There is no need for ordering forms or written instructions for weavers who receive orders verbally. The only metal things in the room are a bucket, scissors, and a few pegs in a woodworking loom. Local water and sunlight and the expertise of the weavers’ hands allow them to pursue their goals and provide for their families.

Conclusion

The survey revealed valuable insights into the traditional crafts, noting significant transformations in design, materials, products, and end markets due to evolving lifestyles and market dynamics. Local wool has largely been replaced by cotton or processed wool, and natural dyes have shifted to synthetic alternatives, while local markets have expanded to a global scale. Younger weavers are increasingly collaborating with NGOs and businesses to explore new markets. They are utilizing finer yarn counts to create saris, stoles, and dress materials in colors and designs tailored to buyers’ preferences. Despite these changes, Dhabhla remains a vital part of life for the people of Kutch, Gujarat.

Acknowledgement

The researcher would like to extend thanks to the master weavers ( Vankar Babu bhai & Vankar Shyam ji bhai) of Kutch for providing their precious time for the execution of the research.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anthropological Survey of India (1998) People of India: Rajasthan. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan Pvt. Ltd.

- Kacker R (1994) Traditional Woven Textiles of Gujarat: Multidimensional Approach. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Faculty of Family and

- Community Sciences, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Department of Clothing and Textiles, Vadodara.

- Chaand A, Yadav A, Sachan K, Tewari N (2011) Shawls and Dhurries of Kutch. Gandhinagar: National Institute of Fashion Technology.

- Torimaru T, Rousso K, Filloy Nadal L, de Ávila BA (2018) Warp and weft twining, and tablet weaving around the Pacific.

- Dholakia K, Mishra J (2018) Preserving identity through geographical indication.

- Singh MH (1891) The Castes of Marwar. Jodhpur: Books Treasure

- Tomar S (2019) Pachhedi-a Study on Vernacular Cotton Textiles of Gujarat (Doctoral dissertation, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda (India)).

- Mishra SS, Mohapatra AD (2014) Women entrepreneurship in handloom sector: prospects and challenges.

- Raval HN, Mevada NP (2015) Kachchh Shawls: Rematerializing Products with Contemporary Motifs using Natural Dyes. A treatise on Recent Trends and Sustainability in Crafts & Design: 3.

- Patel B, Patel HJ, Chudhary NP (2002) A study about motifs & yarns used in artistic weaving of Kutch district (Gujarat).

- https://passionlilie.com/blogs/designersjournal/kutchweaving?srsltid=AfmBOorilk_MVksxHjzXFMUQOg7uuvHnqtxHf_S3pQ1bb6fAXwdS9RHf

- https://gaatha.org/Craft-of-India/bhujodi-weaving-kutch/

- https://kalpavriksh.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Kutch-Short-Report-final-2019.pdf

-

Arooshi and Dr. Neeraj Rawat Sharma*. Weaving Tradition: The Ancient Art of Dhabhla in Kutch. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech 11(3): 2025. JTSFT.MS.ID.000762.

-

Traditional, Vankar, Techniques Dhabhla

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.