Case Report

Case Report

The Uniform Project 2016 – 2023: A Guided Inquiry Approach to Understanding Overconsumption of Fashion Goods

Alexandra Howell Abolo, Associate Professor, Fashion Design, Department of Design, Drexel University, 3501 Market Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Received Date:July 03, 2024; Published Date:July 17, 2024

Abstract

Between 2016 and 2023, a unique project was offered to undergraduate students studying fashion design and merchandising. For seven consecutive days, students were challenged to wear the same outfit, documenting their experience in written and photo journals. This project, originally inspired by Sheena Matheiken’s 2009 “The Uniform Project,” aims to bring the issue of overconsumption more directly into students’ lives. Existing literature shows that consumers generally, and students specifically, demonstrate cognitive dissonance between their understanding of sustainability in the fashion industry and their actions. They often cite the problem of overconsumption while actively engaging in the practice.

Throughout the evolution of the project, the teaching method shifted from problem-based learning (PBL) to a more specific inquiry-based learning (IBL) approach. The guided inquiry approach helped students address the complex problem of sustainability in the fashion industry, particularly regarding overproduction and overconsumption. Student responses and outcomes to the project have always been strong. However, with the integration of IBL, students are demonstrating deeper learning on the subject matter and communicating a sense of agency about sustainability as a cornerstone of their fashion education. The ongoing project aims to inform fashion students about the complexity of sustainability in the fashion industry and build the agency to contribute to long-term meaningful change in the industry.

Keywords:Sustainability; Overconsumption; Guided Inquiry; Problem-Based Learning; Inquiry Based Learning

Abbreviations: PBL: Problem-Based Learning; IBL: Inquiry-Based Learning

Introduction

Sustainability in fashion curricula is nearly ubiquitous. The scope of what sustainability factors are covered vary greatly in both depth and breadth by institution. To that end, sustainability often becomes a buzz word in student lexicons, but carries little meaning beyond the classroom. Existing research suggests that consumer behavior and consumer action are incongruent [1,2]. There is dissonance between what college-aged students (18 – 22 years old) know about sustainable practices, particularly as they relate to the fashion industry, fashion supply chain, and their personal consumption behaviors [3]. Students often perceive their behaviors as sustainable, noting their general knowledge of how the fashion industry is a top contributor to the climate crisis., “…students’ comments confirmed that the project had helped them expand their awareness of how unsustainable consumption behaviors manifest themselves both in theory and in practice” [3]. Student consumption behaviors are often contradictory, purchasing and disposing of fashion goods in rapid succession with little consideration to the lifecycle of a product [4]. Students frequently overconsume fashion goods, contributing significantly to the sustainability issues in the fashion industry.

Denoting the existing literature on the topic of fashion sustainability, cognitive dissonance, and behavior gaps the Uniform Project (UP) was developed. Originally offered in the fall of 2016, the project was adapted from Sheena Matheiken’s (2009) “The Uniform Project,” wherein Matheiken (2009) aimed to wear and style the same A-line dress for an entire year [5]. Matheiken’s original project came to fruition in the early days of internet virality, seeking crowd-sourced donations to fund children’s education in India. Matheiken sought to reinvent her daily look changing only the way she styled the A-line dress with thrifted accessories; her approach was inherently sustainable, not purchasing or disposing of any fashion goods.

After evaluating Matheiken’s work, I saw the potential to use this framework to help undergraduate students grasp overconsumption in the fashion industry. Matheiken repeated a single garment for 365 days, this idea seems outrageous in a system where the average American consumer produces 81.5 pounds of textile waste, annually. This is the byproduct of consuming more and disposing of garments more frequently, “the number of times a garment is worn has declined by around 36% in 15 years” [6]. En masse the U.S. generates 11.3 million tons of textile waste each year [7]. While these Figures are staggering, they often do not resonate, meaningfully to the student population. Matheiken’s worthy endeavor translated clearly as a project in a college course. Using Matheiken’s structure, to wear the same garment, and focus on not buying or wearing anything new. Students are challenged to repeat the same outGit for seven consecutive days, approximately 2% of the total time Matheiken repeated her own outGit. In the case presentation that follows, a more detailed overview of the project is presented [5].

Case Presentation

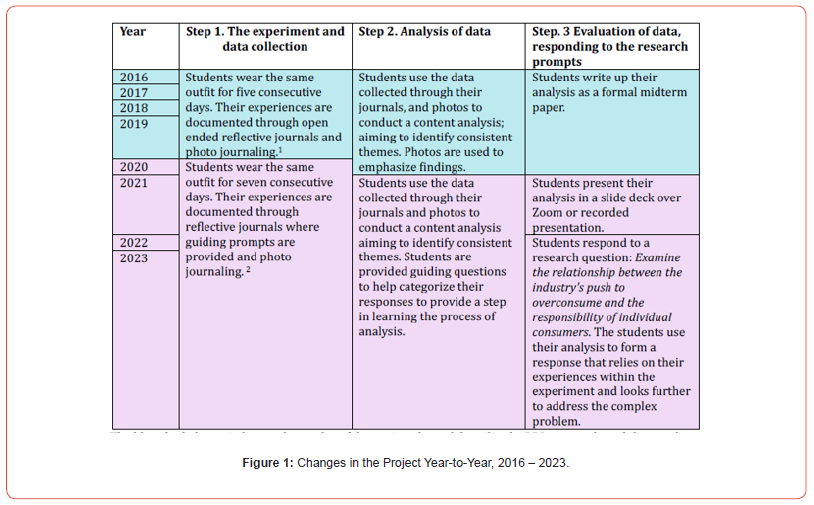

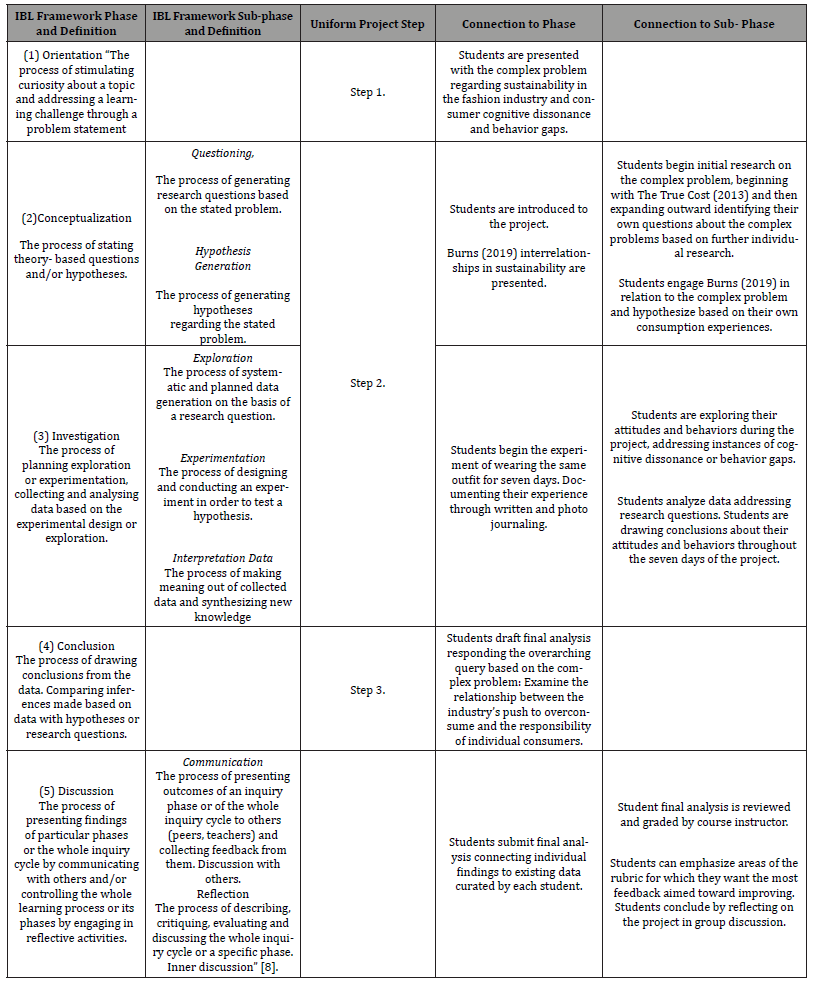

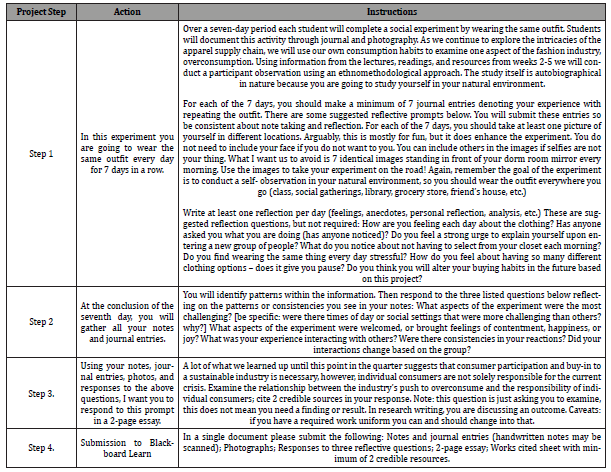

The following case presentation introduces the Uniform Project in its current format. The project is broadly organized into categories that are labeled in the project outline as steps. Step 1. The experiment and data collection; Step 2. Analysis of data; Step 3. Evaluation of data, responding to the research prompts; and Step 4. Submission of project. In Figure 1, the changes to the project year-to-year between 2016 – 2023 are presented and categorized recognizing the transition from PBL to IBL approach. In Figure 2 [8] phases and sub-phases of IBL are defined and categorized to demonstrate how IBL Gits the Uniform Project, Figure 3. Lays out the organizational steps, actions, and instructions for the most recent project cycle, 2023. Finally, Figure 4 is the most recent grading rubric with the IBL phases categorized into the rubric standards.

Table 1:Defining and categorizing the IBL framework phase in connection to the step in the Uniform Project.

Contextual guidance for how IBL framework fits into the Uniform Project.

Table 2:The Uniform Project outline for the 2023 cycle.

The organizational steps, actions, and instructions for the Uniform Project in its most recent iteration, fall 2023.

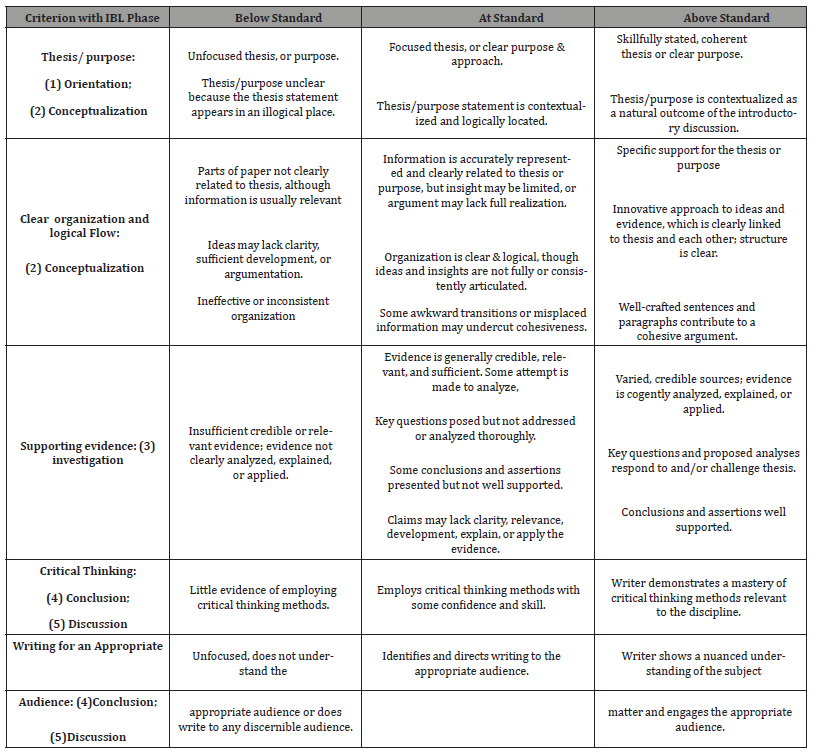

Table 3:Grading Rubric Fall 2023 with IBL Phases Categorized in Rubric Standards.

Contextual guidance for how the Uniform Project is evaluated using the IBL framework.

Guided Inquiry, Problem-Based and Inquiry-Based Learning

In 2016, at the genesis of project development, a problembased learning (PBL) approach was instituted. In PBL students are presented with complex problems often with meaningful realworld outcomes, the students are challenged to seek out resources, to find solutions to the problem” [9]. Compared to a more “traditional” approach where students often receive information from the instructor that layout a problem and provide structural guidance to help the students “solve” the problem. More to the point, students are reciting solutions often learned in a classroom with resources provided by their instructor. To address the complex problem of both sustainability in the fashion industry and the known dissonance and behavior gaps identified among student populations; engaging a PBL approach was logical.

Between 2016 and 2019, the Uniform Project was offered once per academic year for a total of four cycles. Outcomes from two of these cycles were presented at the International Textiles and Apparel Association (ITAA) annual conference in 2019, The Uniform Project Reimagined: An Introduction to Sustainable Fashion for Undergraduate Students.

A total of 35 (n=35) students participated in the project over the two semesters, submitting 245 journal entries and 175 photos. There are several thematic writing patterns that emerged from the student journals stress/anxiety, embarrassment, discomfort, feeling “dirty,” acceptance, and realization. The outcomes of this project are largely positive as students demonstrably grow in their knowledge and understanding of sustainability in the fashion industry. The goal of this project is to help lower-level fashion students gain exposure to sustainability concepts early on in their fashion education. The longer-term goal is that they will apply this knowledge to future coursework to improve sustainability in the fashion industry on a larger scale [10].

Feedback from this presentation assisted in improving the project moving forward. Notably, in initial iterations, engaging PBL, I was prescribing for the students’ questions, research, and ideas which left outcomes to be narrow and canned, lacking full discovery. Further evaluation of PBL as a teaching method introduced inquirybased learning (IBL). The IBL approach provided two significant changes to the project. First, offering students a guided approach to learning the subject matter and second providing greater latitude for discovery on the topic of overconsumption in the fashion industry; thus, allowing students to evaluate questions of dissonance and behavior gaps. The newer versions of the Uniform Project were offered between 2019 – 2023, including during the period of the pandemic (spring 2020 and spring 2021) utilizing an IBL approach.

The blue shaded area indicates that cycles of the project that solely utilized a PBL approach, and the purple shaded area indicates where transitions within PBL aimed to engage guided inquiry via IBL.

Holistic Sustainability

Just as the teaching framework evolved, the application of sustainable theory also evolved. Initially, the project looked at sustainability with a narrow lens, simply at the environmental impact of the overproduction and overconsumption of fashion goods can have. In this vein, students would watch The True Cost documentary, learning about the reaches of the environmental impacts of the fashion industry. The Film aptly introduces social, cultural, and economic sustainability through the stories of global garment workers, farmers, and textile dyers and impacts on their lives. Utilizing, Burns LD [11] an emphasis on a multi-faceted framework of sustainability improved learning outcomes. The focus on the interrelationships between economic,

Pedaste, et al. [8] conducted a meta-analysis on inquirybased learning utilizing n=60 research articles, resulting in the IBL framework that identifies five primary phases of inquiry supplemented by seven sub- phases [8]. At the conclusion of the 2021 project cycle, this framework was mapped onto the existing project. The project was then amended to align with the IBL framework created by Pedaste, et al. [8] to achieve the optimum outcome for the Uniform Project. This new IBL orientated project was offered in the 2023 cycle to significantly positive outcomes.

The original ideation of the Uniform Project from 2016 was adapted between cycles, however, when aligning the project with Pedaste, et al. [8]. IBL framework, the most significant change occurred in phase four, “conclusion, the process of drawing conclusions from the data. Comparing inferences made based on data with hypotheses or research questions” [8]. The notable change from previous iterations of the project was that the students were providing an analysis without any guiding questions. True to the original PBL outline, they aimed to address the large complex problem. However, as the IBL process is structured through Pedaste, et al. [8] the students have latitude to explore within a guided inquiry, thus the query, Examine the relationship between the industry’s push to overconsume and the responsibility of individual consumers, allows students some structure for their responses. In the evaluation section below further exploration of each phase as they align with student outcomes is presented.

Project Outline

The current iteration of the Uniform Project was offered during the 2023 – 2024 academic term in a first-year fashion design class that covers sustainability within the fashion supply chain.

Evaluation

The evaluation of the project is vested five primary areas, as listed below, thesis/purpose; clear organizational and logical flow; supporting evidence; critical thinking; writing for an appropriate audience. As referenced above in the introduction this project transitioned from one that was developed with PBL approach to one now utilizing guided inquiry IBL. The transition of this teaching method created grading categories that align best with the IBL framework.

Students are evaluated on the rigor of their inquiry and not a scale of completion of the experiment overall. The benefits of this create a deeper student investment in the project and willingness to experiment, research, and write with earnest that is divested from the grading outcome. In the discussion I will explore outcomes of the project for which students have failed to complete the experiment timeline but demonstrated a depth of understanding in the meaning of their failure connecting it back to the complex problem of overconsumption in the fashion industry.

Discussion

The importance in examining the changes in the project from its inception in 2016 to the more recent iteration in 2023 demonstrates the value in moving from a PBL-based project to an IBL-based project. Student outcomes and understanding evolved with these changes. As Pedaste, et al. [8] indicates the purpose of IBL is to develop knowledge on a subject to further exploration [8]. In the case of sustainability in fashion, students at the introductory level are better equipped to carry this intellectual curiosity forward, now armed with learning skills that give them agency in the process.

Student outcomes from the changes in this project are significant beginning 2016 and continuing today. In the analysis done in 2019, students often cycled through emotions in the project beginning with anxiety and ending with content often linked to a growth in knowledge or a meaningful change in behavior, “The final two themes acceptance and realization generally come together for a majority of the students at the end of the project. Students begin to examine the amount of clothing they have in their closets” [10]. By integrating IBL into the project students can more meaningfully question why they are driven to purchase more fashion goods. This recognition, minor on the surface, demonstrates a deepening understanding that the corporation and the consumer are responsible for the overproduction and overconsumption of fashion goods.

This expansive understanding of sustainability in the fashion industry, allows students to think more critically about their fashion education and work toward more meaningful change for a sustainable future. This is best evidenced by students who cannot complete the experiment. Commonly, there are usually a small proportion of students who give up on the experiment. Their abandonment is not subversive, often I find these analyses to be the most insightful. These students are questioning why they gave up, what social and environmental influences, both internal and external, brought them to this point. Due to the nature of IBL, students have the latitude to explore the topic and investigate, as Pedaste, et al. [8] describes in phase Give, sub-phase “reflection, The process of describing, critiquing, evaluating and discussing the whole inquiry cycle or a specific phase” [8].

In the most recent iteration of the project, 2023, a student wrote in their essay that they just “gave up,” because they recognized the dissonance in their behavior. The student described a hunger for the end of the project to begin selecting new clothes and styling new outfits. To which they acknowledge, is the problem of overconsumption in the fashion industry. This student concluded by examining their design practice and how they might contribute to change in the industry, and ways they may continue to uphold some standards that are counterproductive to the sustainability movement overall.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Cairns HM, Ritch EL, Bereziat C (2022) Think eco, be eco? The tension between attitudes and behaviours of millennial fashion consumers. International Journal of Consumer Studies 46(4): 1262-1277.

- Kagawa F (2007) Dissonance in students' perceptions of sustainable development and sustainability: Implications for curriculum change. International journal of sustainability in higher education 8(3): 317-338.

- Jestratijevic I, Hillery JL (2023) Measuring the “Clothing Mountain”: Action Research and Sustainability Pedagogy to Reframe (Un)Sustainable Clothing Consumption in the Classroom. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 41(1): 10-25.

- Paulins VA, Hillery JL, Cavender R, Jestratijevic I (2020) Consumer Behaviors Regarding Sustainability that affect Demands Shaping Corporate Social Responsibility Policies in Fashion and Hospitality Industries. International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings 77(1).

- Matheiken S (2009) Year 1 – How it all began. The Uniform Project.

- Igini M (2023) 10 Concerning Fast Fashion Waste Statistics. Earth.org.

- Textiles: Material-Specific Data (n.d.) Facts and Figures about Materials, Waste, and Recycling. Environmental Protection Agency.

- Pedaste M, Mäeots M, Siiman LA, de Jong T, van Riesen SAN, et al. (2015) Phases of inquiry-based learning: DeGinitions and the inquiry cycle. Educational Research Review 14: 47-61.

- Duch BJ, Groh SE, Allen DE (edts.) (2001) The power of problem-based learning: A practical how to for teaching undergraduate courses in any discipline. Taylor & Francis.

- Howell AL (2019) The Uniform Project Reimagined: An Introduction to Sustainable Fashion for Undergraduate Students”, International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings 76(1).

- Burns LD (2019) Sustainability and Social Change in Fashion. Fairchild.

-

Alexandra Howell Abolo*. The Uniform Project 2016 – 2023: A Guided Inquiry Approach to Understanding Overconsumption of Fashion Goods. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech 10(4): 2024. JTSFT.MS.ID.000749.

-

Sustainability, Overconsumption, Guided Inquiry, Problem-Based Learning, Inquiry Based Learning

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.