Research Article

Research Article

Shared Governance for Digital Garment Production: Towards a Dynamic Model

Marco RH Mossinkoff*

Senior lecturer and research fellow @Fashion & Technology Professorship, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Netherlands.

Marco RH Mossinkoff, Senior lecturer and research fellow @Fashion & Technology Professorship, Faculty of Digital Media and Creative Industries, Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, Netherlands.

Received Date: May 26, 2025; Published Date:June 13, 2025

Abstract

The problem with investments in digital technology arise when much wanted and needed small companies and entrepreneurs have to invest in costly device the benefits of which are largely unforeseen, or unpredictable. An example of this is the use of 3D whole garment knitwear machines, there not only the machine itself is costly, not only the outcomes unpredictable in terms of sale, but also and mostly the development of knowledge necessary to create and translate fashion into informatic tools is more unique than rare. In the specific case of fashion as a creative industry, unpredictability of outcomes poses serious problems to making joint investments. So how can multiple small companies best share such investments and benefits from these? Mostly in the context of local production (eco)systems, this is a fundamental question to be answered. In this paper we further elaborate on the question using the pivotal framework as developed by Ostrom E [1] and further elaborated by Bridoux F, et al. [2]. We discuss three possible collaborative frameworks in the specific context of fashion and textiles production.

In the paper we look at the case of a shared 3D whole-garment knitwear machine to test and further develop this framework of collaboration. The paper ads to theoretical knowledge where we do contribute to adding insights from the creative industry into existing knowledge of collaborative efforts, or the literature on shared ownership, which is mainly applied e.g. in the context of finance of real estate ownership. The practical relevance lies in the applicability of the model to implement and foster the use of technologies carrying a high financial risk, to promote local, communitybased ecosystems of production (and consumption).

Keywords: Ownership; Governance; Commons. Creative Industries; 3D Fashion

Introduction

The textiles and fashion sector are still considered one of the most labour intensive ones. Nevertheless, digital production technologies could change that picture, moreover the use of 3D production technology allows for the creation of better products that are more aligned with the needs and preferences of the client. Recent developments underscore the potential of digital production technologies in fashion. For example, Unspun’ s collaboration with Walmart to produce 3D-woven work pants demonstrates how 3D weaving technology can reduce emissions and waste typically associated with traditional textile production.

Designers are involved in the production process, allowing them to experiment and easily adapt products to meet design requirements (both aesthetic and functional) as well as production possibilities. This process is currently very time- and energy consuming. The product could be better aligned with its intended use. For example, different parts of a garment may require different resistance properties. These can quickly be modeled, virtually tested, and produced and on-demand production could become an affordable reality.

In theory, an instance of a so-called ‘virtual supply chain’ is possible, where collaborations temporarily come together to achieve a specific goal (the creation of a collection).

However, a typical chicken-and-egg dilemma still exists: the costs of producing digital knitwear are still too high, making the price of a product too high to reach the economies of scale necessary for mass production. This is also tied to the well-known ‘standard setting’ problem: machines from different companies and brands must be able to communicate seamlessly. Shared ownership of resources would undoubtedly help overcome these challenges. A further step involves the need to develop shared databases accessible to everyone.

Lastly, but importantly, there is a shortage of specialized personnel.

In order to address these issues, we have formulated the following questions:

How is it possible to create and manage a joint institution responsible for the development of knowledge (and thus the training of personnel) in this area? Sub-questions include: What knowledge is already available and usable? How can the acquisition of such knowledge be made attractive?

What are the conditions for the successful establishment of spontaneous, ad-hoc, flexible, yet goal-oriented temporary collaborations? And how can these be used to advance a ‘designdriven’ business model where products are continuously tested for market acceptance?

What are the requirements for a secure environment (business, contractual) that facilitates the exchange of ‘sensitive’ information?

Following we try answering these questions but first giving a short literature overview on topics related to shared governance applied to the 3D textiles production context. We have also done an exploratory case study empirical research that combined with the findings from the literature review has led to the creation of a governance model ‘specifically’ adapted for the creative industries.

The topic pf shared governance has been dealt with, one could say, from when the first men species became sedentary and started breeding cattle. Still now the common governance of natural resources however presents an issue [3]. Not intending to go back to the origins of man species, Garrett Hardin’s influential article “The Tragedy of the Commons” [4] argues that the lack of regulation and private ownership leads to the depletion of common resources. This has led to discussions about government action versus market mechanisms [5,6]. This theory resulted in the privatization of many common resources, such as energy production and telecommunications. Elinor Ostrom’s commons theory [1] emphasizes that communities can sustainably manage shared resources without private ownership or government intervention. This requires clear rules developed and enforced by the community. In the realm of digital data sharing this presents typical problems, so the case for digital information presenting new challenges of common governance brings again under the attention the problem of common ownership and how to organize that [7].

Ostrom’s theory challenges the idea that only government intervention or private ownership guarantees sustainability. She advocates community-based management, which has led to projects such as cooperatives and community land trusts. More recently Tiwana A [8] explores platform evolution, focusing on how governance mechanisms adapt to co-evolving platform architectures and dynamic environmental conditions. Tiwana emphasizes that platform governance must balance control and flexibility—a concept that can be applied to the shared use of digital knitting machines and technology in fashion. Tiwana introduces the importance of modular governance in dynamic environments, where governance is not static but evolves with changes in technology and market demands. This modularity can be applied to the fashion industry, where small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) need flexible governance models to manage shared digital resources, such as 3D knitting machines. Tiwana’s framework helps explain how fashion companies can manage shared ownership of digital assets. By using governance models that adapt over time, SMEs can better manage shared investments, technology standards, and resource control. For European SMEs looking to share digital machines and resources, Tiwana’s insights on platform governance provide a framework for controlling access to shared resources (such as knitting machines) and ensuring fair distribution of benefits, such as shared profits or data insights. Several authors, including David Bollier [9] and Yochai Benkler [10], have written about commons-based economic approaches and the role of digital technologies. Benkler argues that decentralized governance and open access to resources can lead to innovation by enabling individuals to contribute according to their skills and interests. This can be directly applied to how fashion designers, manufacturers, and technologists collaborate on shared platforms or technologies like 3D knitting machines. Benkler’s work also highlights the potential for peer-to-peer collaboration in the digital fashion industry. For SMEs in Europe, adopting a commons-based approach could enable them to share technologies and innovations freely, fostering a creative ecosystem that is competitive with larger companies.

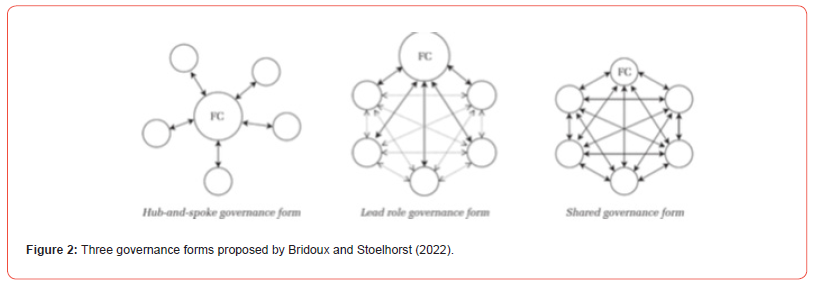

Building on Elinor Ostrom’s work, Bridoux and Stoelhorst propose three governance forms: hub-and-spoke, lead role, and shared governance [11]. This model balances centralized leadership with stakeholder input, ensuring equitable access, efficient resource management, and conflict resolution. However, while shared governance promotes fairness, it may slow decisionmaking in fast-moving sectors like fashion. Moreover, in the specific case of fashion as a creative industry, unpredictability of outcomes poses serious problems to making joint investments [12].

Methodology

To build upon the models that have been briefly introduced above, an iterative, interpretive approach has been applied as it is the most appropriate in the context of a ‘real world problem’ that needs to be further explored and at the same time tested using theoretical insights. That means that the data collected during meetings and workshops have been collected in a ‘semi-structured’ way; the sample was purposive as each data collection phase has led to refining the outcome, or final framework, and vice-versa.

For this research we have looked at the specific case of a 3D Wholegarment Knitwear – Shima Seiko - machine project held at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences. In this project, multiple iterations have been made in order to come to an end product that would be satisfactory for all partners involved. An example of these partners involved are the University itself, Musea, Fishing organizations (as the project regarded the making of a personalized fisherman’s sweater, see this link for more details).

Results and Analysis

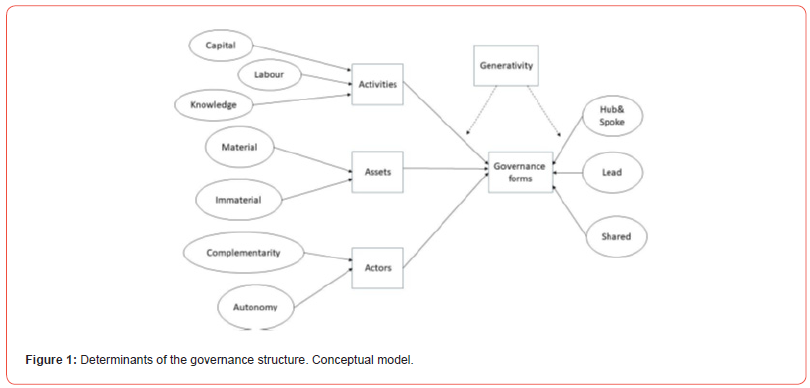

The iterations between data collection and literature exploration have led to the creation of the model as depicted underneath that will serve as the basic framework for the Fluid Ownership (solid benefits) prototype (Figure 1).

In the above Figure 1 you can see three forms of governance, as represented by the dependent variables, taken from Bridoux and Stoelhorst’s classification. Recently the author has claimed that their approach is anything but static and well integrates in a more systemic perspective, as we envisage to do [2]. In the following picture FC stands for the focal firm, and the virtual networks composed of stakeholders and relationships formed around this initiative taker are shown. Amore specific graphic representation of these is given in Figure 2.

Factors leading to different configurations can be classified according to the three inputs employed resources. These are: Activities, Assets, Actors.

Activities

Capital intensive activities are typically those where negotiations are held to discuss allocation of resources. These can be complex and intertwined, as well as clearly defined beforehand (as is the case with external financing and legislative safeguards that are due to e.g. standard terms of trade). In the context of a digital knitwear machine the costs involved amount to about 200 thousand Euros (for a Shima Seiki Wholegarment machine, indicative price, the final one is depending on the requirements). Several actors can be involved in the initial financing process, but also one party (the focus firm) could take up this investment. That leads to different decision- and hence governance structures.

Even though the aim is to automate the production of a garment, this is still a relatively labour intensive process. The labour process on the other hand knows a very steep learning curve. Developing the software and modifying designs according to the requirements of the machine requires a continuous trial & error process the outcome of which is for a large degree uncertain. However, once a standard is set, the production does not require much labour intensive activity, except for monitoring.

Knowledge sharing is the most delicate of activities. Combining people from a design, more creative and aesthetics- based and a software engineering background is a major challenge.

Depending on the level of complexity these activities may require different governance structures. Where for example the terms of trade in the industry are set (financial investments) and the outcomes in terms of expected production are easy to define, the governance structure will be more explicit. Where the collaboration between designers and software developers is more complex and surrounded by uncertainty, governance structures are more open and less formal.

Assets

Material assets involve the machine itself, as well as the inventory needed to produce the garments. This inventory is specific, because the yarns needed to produce the garment with such machine need to be particularly long and resistant. These, for now, cannot be produced in the Netherlands for a viable price and need to be important, mostly from Italy. This means these investments have a somewhat disposable nature. That is also and mostly true for immaterial assets, that is the knowledge produced. In as much as a large part of the software coding can be applied interchangeably on different machines, that design characteristics are not because of the physical requirements, but also because of the competitive issues involved (see the part about ‘actors’ underneath). The extent to which these assets are or are not reusable (or else: the extent to which these can be shared and used again by different stakeholders) has consequences for the governance structure, whether this is more formal and centralized, or not.

Actors

We have used the term ‘stakeholders’ a few times. This term implies some degree of goals alignment. In the literature ‘goal alignment’ is one of the major drivers of ‘good governance’ or due diligence in structuring and mostly managing the governance structure. Although the final success of the enterprise is in everyone’s interest, the extent to which one party benefits more, or less then another one can lead to problems due to unbalanced feelings of equity (a large part of the literature shows that perception of equity does have a large impact on economic and non-economic satisfaction). Moreover, complementarity also regards the level of interdependency amongst partners; whether the activities of one stakeholder are for instance necessary or not for the other to be able to work. Complementors can be High or Low autonomy ones, where the latter are more involved technically in the value creation process; in the mechanism that lays at the basis for the collaboration. Taken together another characteristic of the system is ‘generativity’ which is defined as the “overall capacity to produce unprompted changes driven by large, varied, and uncoordinated audiences” [13]. High levels of complementarity and autonomy ask for more explicit and formal contracting, whereas more competitive yet less autonomy-based collaborations ask for more complex, implicit governance structures.

Conclusions

This project on fluid ownership within the creative industry highlights the importance of collaboration, shared resources, and innovative governance structures in fostering sustainable development in sectors such as digital knitwear production. The proposed fluid ownership model introduces a shared governance framework, where stakeholders collectively manage high-cost resources like digital knitting machines, software, and expertise. This model not only lowers the financial barriers for smaller companies but also encourages collaboration between designers, manufacturers, and technologists, resulting in a more flexible, adaptive, and inclusive ecosystem.

The project underscores the potential for this governance model to address critical challenges, such as the lack of specialized personnel and financial means, technological risks, and the cultural acceptance of digitally produced garments. By emphasizing the importance of shared decision-making, , the model promotes both economic efficiency and social equity.

To address further research, we are interested in knowing about other cases on horizontal collaborative efforts based on new technologies in the fashion and textiles sector, as well as in existing studies which look at these governance forms from a more dynamic, evolutionary perspective.

Acknowledgements

This research project is an initiative of the Centre of Economic Transformation, as a collaboration between the professorship of Fashion Research and Technology and the professorship of Corporate Governance and Leadership at the Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences. I wish to thank the funding organization ‘Regieorgaan SIA -KIEM’for granting the funds. I also am indebted to Deborah Tappi for her contributions, and to Troy Nachtigal and Fran Jan de Graaf for the fruitful collaboration.

Conflict of Interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Ostrom E (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Bridoux F, Stoelhorst JW (2024) The Problem of Stakeholder Governance. Business Ethics Journal Review 11(3): 15-21.

- Becchetti L, Bova DM, Raffaele L (2025) Win together or lose alone: Circular economy and hybrid governance for natural resource commons. Journal of Cleaner Production 486: 144520.

- Hardin G (1968) The tragedy of the commons. Science 162(3859): 1243-1248.

- Theriot M, Block WE (2024) Navigating Past the Tragedy of the Commons. Journal of New Finance 3(3): 1.

- Wejnert B (2025) The Tragedy of the Commons Revisited. The Global Rise of Autocracy: Its Threat to a Sustainable Future.

- Bühler MM, Calzada I, Cane I, Jelinek T, Kapoor A, et al. (2023) Unlocking the power of digital commons: Data cooperatives as a pathway for data sovereign, innovative and equitable digital communities. Digital 3(3): 146-171.

- Tiwana A (2010) Platform Ecosystems: Aligning Architecture, Governance, and Strategy. Morgan Kaufmann.

- Bollier D (2021) The Commons: A New Narrative for Our Times. Amherst College Press, USA.

- Benkler Y (2013) The Penguin and the Leviathan: How Cooperation Triumphs Over Self-Interest. Yale University Press, USA.

- Bridoux F, Stoelhorst JW (2019) Stakeholder governance: Solving collective action problems in stakeholder ecosystems. Academy of Management Review 44(3): 363-385.

- Mossinkoff MR, Stockert AM (2008) Electronic integration in the apparel industry: the Charles Vögele case. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 12(1): 90-104.

- Zittrain J (2005) A history of online gatekeeping. Harv JL & Tech 19: 253.

-

Marco RH Mossinkoff*. Shared Governance for Digital Garment Production: Towards a Dynamic Model. J Textile Sci & Fashion Tech 11(4): 2025. JTSFT.MS.ID.000768.

-

Forecasting, Demand, Fashion, Social network

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.