Research Article

Research Article

Trends and Strategies of International Cooperation Against Terror: Terrorist Conflicts and United States’ Security Assistance in Nigeria Revisited

Okeke, Christian Chidi Phd1* and Ezeamama, Ifeyinwa G. Phd2

¹Department of Political Science, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria

²Department of Political Science, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu University, Igbariam Campus, Anambra State, Nigeria

Okeke, Christian Chidi Phd, Department of Political Science, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State, Nigeria.

Received Date: June 20, 2023; Published Date: July 05, 2023

Abstract

The study examined the nexus between terrorist conflicts and the United States’ security assistance in Nigeria within the ambit of international cooperation against terror. For over a decade now, Nigeria has witnessed some of the most devastating terror attacks in the world by sub-national groups, such that it is consequently classified as one of the most dangerous and terrorized states globally. Between 2015 and 2021 in particular, over 2,470 terrorist incidents were recorded with over 17, 751 deaths and 7, 345 injured, among which were 318 suicide acts. This has continued regardless of the foreign security assistance from the international community, particularly the United States Government.

The key concern, therefore, is the factors that may have constrained the effectiveness of this assistance. Anchored on the relative deprivation theory, the qualitative mechanism of data collection and analysis was applied in the study. Among other things, the study found out that Nigeria is grossly constrained in terms of financial, technological, and military-related possessions to solely and effectively tackle terrorism in her territory, thus necessitating security assistance from the United States Government. It also found out that the assistance is threatened by certain factors including gross human rights violations perpetrated by Nigeria’s security forces. In view of the findings, the study therefore recommended the need for swift security reform and huge investment in military technology, training, increase in personnel and proper funding for better anti-terrorism outcome.

Keywords:Terrorism; security assistance; US Government; Nigeria; Boko Haram

Introduction

Terrorism in Nigeria has assumed a more dangerous and audacious dimension since 2009. As a seed sown in early 2000, the terror campaign championed by the Boko Haram sect and its Islamic-State-affiliated splinter faction, the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), has today become complicated and circumventing what could have become international solidarity towards containing the challenge and wiping its impacts. Issues of corruption among the political elites, worsened by desperation and poverty by impoverished Nigerian youths mainly led to terrorism upsurge [1]. The net effect is that the country ranked third in the list of most terrorized countries in the world in 2019 for a six consecutive time since 2014 behind Afghanistan and Iraq with an index of 8.6 [2].

Today, Nigeria is at crossroads as a result of terrorism. National development has stagnated. It amounts to misnomer to say that Nigeria has witnessed development [3]. In fact, the terrorists have succeeded in holding Nigerian government hostage [4]. Worse still, the security assistance from the United States Government to support the war against terrorism seems to have been constrained by certain factors. There have been calls for an evaluation of how the United States security assistance has assisted the war against terrorism in Nigeria from 2015 to 2021.or otherwise and to suggest steps that need to be taken in order to make the United States security assistance to Nigeria on war against terrorism effective. Previous studies have paid scanty attention to this concern. This study was therefore undertaken to fill that gap by carrying out an evaluation of the correlations between terrorist conflicts and the United States security assistance in Nigeria from 2015 to 2022.

Statement of the problem

Providing security for citizens is a duty that is of paramount importance to every responsible government. It is seen as a topmost priority since actualizing developmental objectives of the State depends on provision of security. Broadly speaking, achieving world peace was not only the main concern of the defunct League of Nations but is the most important reason or purpose for the United Nations Organization. Beyond that, more advanced economies have come to embrace the task of assisting less developed countries to effectively tackle their security challenges. In particular, the United States of America has taken the lead in this direction since September 11, 2001 terror attack on the soil of the U.S. The U.S. interest in maintaining zero tolerance for international terrorism gave rise to the establishment of Section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act 2001 (as amended) which empowers the U.S. Secretary of State with the approval of the President to designate any violent group(s) found to be involved in terrorist activities outside the United States and whose activities are a threat to the United State security as foreign terrorist organization [5]. Principally, it is believed that such measure can help to tame the tide of international terrorism. In particular, the U.S. Government has provided security assistance to Nigeria in order to strengthen counterterrorism efforts of the latter. This cuts across a widespectrum of security concerns. For instance, from 2016-2020, the Department of State provided $7.1 million in International Military Education and Training (IMET) funding to the Nigerian military [6].

Be that as it may, that Nigeria faces multifaceted security challenges, particularly terrorism, has been established. As Okeke and Omojuwa [7] aptly pointed out, many challenges currently plague Nigeria’s federalism. The challenge is that the situation has worsened over time and has become the defining characteristic of the Nigerian geo-political space. It has lingered since the politics and policies of the ruling elites are characteristically skewed to exclude and disfavor most of the citizens. For instance, Nurudden [1] averred that the substantive issue of poverty experienced by the impoverished youths and the inability of the leaders to accord attention to the social, economic, and political contradictions in the country mainly led to Boko Haram upsurge and provided a fertile ground for the upsurge.

Today, Nigeria is ranked as the world’s third most terrorized country, after Afghanistan and Iraq [8]. Not only is the country regarded as one of the most dangerous countries with devastating attacks, the risk of terrorist attacks in Nigeria over the past years can only be classified as extremely high [9]. Boko Haram, in particular, has been responsible for thousands of deaths throughout the Lake Chad Basin region of West Africa as the salafi-jihadi insurgency has led to 35,000 combat-related deaths and 18,000 deaths from terrorism since 2011, mainly in Nigeria [10]. It accounts for largescale displacement, several incidences of kidnapping, death, and injuries [11]. In fact, there were more than 2 million internally displaced persons in Nigeria as of 31 December 2018 largely attributed to the rampage by terrorists in the country [12]. The key concern, therefore, is to what extent has the assistance by U.S. helped the war against terror in Nigeria, particularly from 2015- 2022? What factors constrain the effectiveness of assistance on the war against terrorism? These are the core issues which this study sought to investigate.

Objectives

The broad objective of the study is to examine the correlations between terrorist conflicts and the United States security assistance in Nigeria from 2015 to 2022.

The specific objectives are:

i. To examine how terrorist conflicts have engendered United States security assistance in Nigeria from 2015 to 2022.

ii. To interrogate the factors that constrained the effectiveness of United States security assistance against terrorist conflicts in Nigeria from 2015 to 2022.

iii. To suggest steps that need to be taken in order to make United States security assistance to Nigeria effective.

Research questions

The following research questions were formulated to guide this study:

i. How has terrorist conflicts engendered United States security assistance in Nigeria from 2015 to 2022?

ii. What factors constrained the effectiveness of United States security assistance against terrorist conflicts in Nigeria from 2015 to 2022?

iii. What steps need to be taken in order to make United States security assistance to Nigeria effective?

Methods

The qualitative mechanism of data collection and analysis was applied in the study. In essence, documentary method for data collection was adopted in this study where secondary sources of data were utilized. As such, data were collated from institutional materials, conference papers and journals, among others while qualitative descriptive method was used for data analysis.

Theoretical framework

This study is anchored on relative deprivation theory which offers an explanatory inroad into the causative factors that underlie collective actions. It holds that feelings of deprivation and frustration account for individuals’ decisions to engage in collective action (Grenshaw, cited in Adedire et al., 2016).

Basically, the relative deprivation theory is attributed to a sociologist, Samuel A. Stouffer whose work on relative deprivation was representative of the shift in sociology from a focus on social reform to theory. It attempts to postulate on the origins of social movements or deliberate voluntary effort to organize individuals who act in concert to achieve group influence and make or block changes.

According to Adedire et al., [13], the central idea of relative deprivation theory suggests that individuals or groups feel deprived when their current circumstances are negatively compared to the situation of others. By implication, the relative deprivation theory is a view of social change and movements according to which people take action for social change in order to acquire something (for example, opportunities, status and wealth) that others possess and which they believe they should have, too. This condition therefore engenders violence within the given society.

This theory aptly reveals the intrinsic cause of terror-linked violence, in this context, in Nigeria. In other words, the conflict is orchestrated by deprivation experienced by the actors who resort to violence against the Nigerian State as a result. Effectively tackling the conflicts requires not just local efforts but international collaboration. It is in this context that unearthing the challenges to the United States security assistance on the war against terrorism was made the central objective of this study.

Review of Literature

Terrorism: perspectives and trends

Terrorism is a concept which does not easily yield itself to a single internationally accepted definition. The term is inherently difficult to use in a precise or unequivocal way [14]. In essence, it has been variously defined by different authorities such that there are as many definitions of terrorism as there are people, scholars and institutions grappling with it [15,16]. In fact, Simon cited in Onuoha, [16] identified no fewer than 212 different definitions of terrorism in use, with 90 of them used by governments and other institutions.

The avalanche of definitions associated with the concept of terrorism has been traced to a number of reasons. For instance, Wilkinson [14] attributed this to three reasons. First, according to him is that the concept is frequently employed in a number of undifferentiated ways to mean variously a concept, human activity, felony, specific event, an emotion, method of intimidation or condition of being terrorized. The second is that the concept is emotion-laden with expressive content, the function of which is to evoke feelings, attitudes, or emotions. This emotive quality therefore causes distortion when attempting to communicate a precise meaning. Third is the problem of achieving a precise definition, one that would be universally acceptable.

On the other hand, Cronin [17] situated the problem in the fact that the concept is intended to be a matter of perception and is thus seen differently by different observers. This is obviously the point that Onuoha [14] tried to argue and which must have prompted Toros [18] to insist that any article on terrorism must enter the labyrinthine debate on what the concept means and how it is to be defined. Precisely, that could have dragged this study into undertaking the enormous task of attempting a conceptual clarification which brings out the various debates on what the concept represents as postulated by the different scholars.

Be that as it may, the concept, like its social sciences counterparts, has been viewed from liberal and radical lens. In other words, liberal and radical scholars have as usual congregated around their various schools of persuasion to attempt definitions of the concept. This is the point which Onuoha [14] tried to make when he argued that efforts have been made to explain the meaning of terrorism from two major perspectives. He went further to hint that liberal scholars use the concept in a pejorative connotation. According to him, this group of scholars attaches the label of terrorism to some acts of violence whose underlining objective they do not accept such that if one side to a dispute succeeds in attaching the terrorist label to its opponent, it has gained an important psychological advantage.

To that end, liberal scholar Edward [14] defined the concept as the use or threat of use of anxiety-inducing extra-normal violence for political purposes by an individual or group, whether acting for or in opposition to established governmental authority, when such action is intended to influence the attitudes and behaviours of a target group wider than the immediate victim. In essence, one can say that liberal scholars agree that terrorism involves the use of violence for the actualization of politically related objectives. Another point that is worth stressing is their belief that terrorism can be initiated and supported by governmental authority. The import is that those in authority can, indeed, deploy terrorism as a strategy to meet certain premeditated objectives. Little wonder that the concept of state-sponsored terrorism has been introduced into the terrorism lexicon.

Conversely, radical scholars view terrorism from the prism of forms of protest and political participation which have moral foundation expected of normal members of a society who are desperate for one reason or the other. Thus, Mojekwu [14] argued that the atrocities associated with terrorism, although reprehensible, should rather be viewed as acts of protest which the technological and modern society has neglected to look into at the initial stage. What his argument implies is that radical scholars have unflinching persuasion that terrorism is not, after all, an insane act premised on or motivated by an inherent urge towards destruction.

Irrespective of the divergent opinions on terrorism as canvassed by liberal and radical scholars, however, the consensus remains that certain characteristics distinguish terrorism from other forms of violence. The first is that the act must be violent, whether premeditated or instantaneous. Second is that the direct targets of such violent attack are usually non-combatants who usually do not have direct relation or influence on the real motive behind the attack. Third is that the act takes place largely in an environment of relative peace. And fourth, the ultimate motive for the violence is to cause fear in the psyche of the public in order to influence those in political authority to respond to the demands of the individual or group behind the attack [14,16,19]. In essence, traditional crimes centre around their victims, are motivated by material acquisition, and executed without the need for publicity, contrary to terrorism.

In contributing to the debate, Institute for Economics and Peace [8] noted that in order to be included as an incident in the global terrorism data, the act has to be an intentional act of violence or threat of violence by a non-state actor, meaning that an incident has to meet three criteria in order to be counted as a terrorist act, which are:

i. The incident must be intentional-the result of a conscious calculation on the part of a perpetrator.

ii. The incident must entail some level of violence or threat of violence-including property damage as well as violence against people.

iii. The perpetrators of the incidents must be sub-national actors.

However, it highlighted that in addition to the baseline definition, two of the following three criteria have to be met in order to be included in the national consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) database:

i. The violent act was aimed at attaining a political, economic, religious, or social goal.

ii. The violent act included evidence of an intention to coerce, intimidate or convey some other message to a larger audience other than to the immediate victims.

iii. The violent act was outside the precepts of international humanitarian law.

Be that as it may, those are some of the differences in distinguishing between terrorism and other crimes and explain why, regardless of his deficiency in not holistically taken into account all the essential characteristics of the concept, Radu [20] defines terrorism as any attack or threat of attack against unarmed targets intended to influence, change or divert major political decisions. The view is echoed by Igwe [21] when he contended that terrorism is a premeditated attack against non-belligerent targets and an activity aimed at intimidating the opponent either through covert, unconstitutional or unlawful warfare, or the use of illegal weapons and methods, sometimes in an undeclared and ill-defined war, with doubtful political objectives.

Practically, the view captures the irreducible elements of terrorism and accounts for why the definition given to terrorism by the Institute for Economics and Peace [8] as the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to obtain a political, economic, religious or social goal through fear, coercion or intimidation is inadequate to the extent of its silence on the victims, despite expanding the scope of the goals of the perpetrators, unlike other clarifications by some scholars. In essence therefore, one can say that terrorism symbolizes adaptive strategies and rational acts of violence by aggrieved persons or groups which instill fear and cause discomfort among victims necessarily not influential among real targets for the purpose of extracting political and indeed multilayered purposes.

Basically, apart from state and state-sponsored or executed terrorism whose effect is felt the other way round, many of the acts of terrorism carried out by individuals and groups are targeted at governments. However, those who fall victims have little or nothing to do with the very grievances complained against by the perpetrators, and this is almost the case all the time. Also, incidences of plane hijackings and bombings, street explosions, hostage takings, public water and environmental poisonings, train derailments, road vehicle attacks and extra-judicial murders, the killing and poisoning of individuals and public figures, hired assassinations, and other forms of criminal bloodshed and blackmail are acts which had been part of the 20th century’s legacy of terrorist conflicts by sundry organizations and individuals [21]. And these have remained conspicuous features of terrorism in the 21st century.

Causative factors of terrorism in contemporary nigeria

Various attempts have been made by scholars to explain the causes of terrorism in contemporary Nigeria. In essence, available literature is replete with what they consider as the genesis of terrorism in Nigeria, some of which are, however, a misrepresentation of facts; therefore, highly defective. For instance, Olisa et al. [15] opined that terrorism crept in Nigeria through the ideas, public statements and secret activities of unhappy politicians and public figures frustrated by the overall result of Nigeria’s 2011 presidential elections from which Dr Goodluck Jonathan emerged as the president. As they wrongly asserted, these frustrated politicians rejected the success of Jonathan and stated that they would make governance difficult in Nigeria if the results of the 2011 presidential elections were not cancelled and some months later, the terrorist group now known all over Nigeria as Boko Haram emerged and began terrorist activities in Nigeria. This assertion, however, is highly misleading, biased and smacks of ignorance of the facts.

However, before examining the crux of origin of terrorism in contemporary Nigeria, it suffices to point out, as enunciated by Igwe [21], that terrorisms whether local or international, have their roots in the nature of the domestic policies of nations within which the gangs germinate and against which they supposedly act. Put differently, what supplies oxygen for survival of terrorism in any given geo-political space is undetached from local politics and policies which are characteristically exclusive. It is usually against these unfavourable, and mostly unjust elitist practices that the deprived persons attempt to upturn through multi-dimensional terrorism.

Principally, both Nurudden [1] and Oyeshola [22] agree to the fact that the Boko Haram upsurge in Nigeria, for instance, can be situated within the context of structural violence where the identifiable culprit is the government represented by the operating social system which deprives the victim (mainly a section of the citizens) through differential access to social resources. By implication, it is safe to say that the bulk of Boko Haram members are victims of willful deprivation who are pushed to the wall to exploit the prevailing political and social norms to vent their grievances against the state. And this is based on the belief that a frustrated citizen is likely to be less committed to the stability and continuity of a system he/she views as a failure.

It is this fact that drove Nurudden [1] to aver that the substantive issues of corruption, desperation and poverty experienced by the impoverished youths and inability to accord attention to the social, economic and political contradictions in the country mainly led to Boko Haram upsurge. He even went further to insist that it is these avoidable contradictions that provide fertile ground for the upsurge because idle people living in destitution can easily be recruited into any form of mischief. Also, Oromareghake et al., [23] minced no words in lamenting that the youths engage in self-seeking and criminal activities with a unifying factor in not being satisfied with their present state.

Historical facts underlining terrorism in Nigeria

Nurudden [1] has considered immediate and remote genesis of terrorism in Nigeria by focusing on Boko Haram. As such, he contended that the Boko Haram as a sect and movement started in Maiduguri as Al-Shabbah (translated as the youth) on the eve of Nigeria’s return to civil democratic rule in 1999 with people associating them with different names like Yusufiyya (coined from the movement leader’s surname Yusufu) and others simply calling them Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal Jihad. As such, it was founded as a Salafist Muslim reform movement but has expanded since 2009 to become one of the world’s deadliest terrorist groups to the extent that the United State Department has designated Boko Haram, IS-WA, and a separate splinter faction known as Ansaru as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) under Section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (as amended) and as Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs) subject to U.S. financial sanctions under Executive Order 13224 [24].

Internal rifts led Boko Haram to split into factions, which now appear relatively distinct with the largest splinter group being the ISIL-aligned Islamic State West African Province (ISWAP), led by Musab al-Barnawi. ISWAP is reported to control territory on the shores of Lake Chad and collect taxes in north-east Nigeria while the rival to ISWAP is the Shekau faction, once led by late Abubakar Shekau. While ISWAP predominantly targets the Nigerian military and government agents, the Shekau faction is known for considering any Muslims that do not follow him as potential targets. And this ideological difference is thought to have motivated their split [25].

Incidentally, Boko Haram was among the four terrorists’ groups- Taliban, Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, and the Khorasan Chapter of the Islamic State-responsible for the most terrorism deaths in 2018 with 9, 223 deaths, representing 57.8 percent of total deaths in that year [8]. In fact, Boko Haram maintains leads in terror organization causing most deaths globally as shown in Figure 1.

implication of the figure is that for the first time since 2013, ISIL was not the deadliest terrorist group as it was overtaken by the Boko Haram. Today, terrorist conflicts in Nigeria have earned the country the status of one of the most-terrorized countries of the world. Table 1 highlights the global ranking on world’s most terrorized countries.

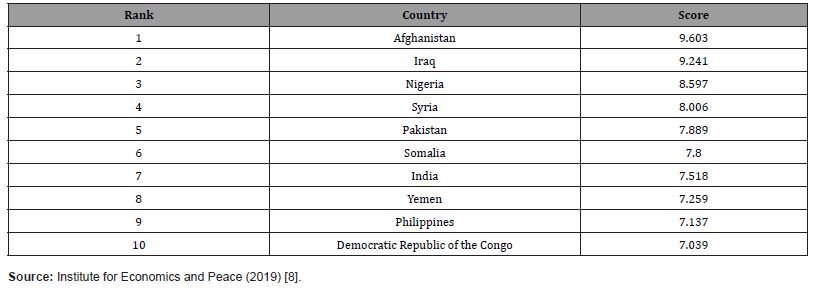

Table 1:World’s 10 Most Terrorized Countries, 2019

As the table shows, Nigeria occupied third position and ranked among the countries with very high impact of terrorism globally. In 2019 in particular, the country garnered a score of 8.597 to trail Afghanistan and Iraq which had 9.603 and 9.241 respectively.

Periscoping general aspects of nigeria-US relations

For centuries now, Nigeria and the United States of America have maintained robust relations. Those relations cover many fields and have remained dynamic. In fact, scholars believe that the interactions between both countries are strategic as a result of strong factors which characterize the two sovereign states. Instructively, the U.S.-Nigeria ties improved after Nigeria’s transition to civilian rule in 1999. The prime of it is often associated with President Trump’s phone call to President Buhari in 2017 which was his first to any sub-Saharan African leader. Also in April 2018, Buhari became the first sub-Saharan African leader to meet with President Trump at the White House.

According to Nagy [26], Nigeria is the United States’ secondlargest trading partner in Africa, with over $9 billion in two-way goods trade in 2017. As he pointed out, hundreds of American companies already operate in Nigeria, and in 2017, U.S. investment stood at $5.8 billion. Practically, Nigeria routinely ranks among the top recipients of U.S. foreign assistance globally. Available records indicate that the State Department and the agency for international development, USAID, allocated $451.4 million in bilateral aid for Nigeria in 2020, nearly 90% of which supported health programs. The State Department and USAID allocated $468.6 million in humanitarian funding in response to the Lake Chad Basin crisis in 2019, including $346.9 million for Nigeria [27].

United States Department of Commerce [28] reported that as of 2019, Nigeria was the United States’ second-largest trading partner in sub-Saharan Africa (after South Africa) and third-largest beneficiary of U.S. foreign direct investment in the region (after Mauritius and South Africa). Notably, Nigerian exports to the United States are dominated by crude oil, which at $4.4 billion accounted for 88% of U.S. imports from Nigeria in 2019. Equally according to U.S. International Trade Commission data, Nigeria consistently ranks as the top source of exports to the United States under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA, P.L. 106-200, as amended) trade preference program; crude oil accounts for nearly all such exports. Conversely, Nigeria is a major regional destination for U.S. exports of motor vehicles and refined petroleum products (e.g., gasoline), which are among the fastest-growing U.S. exports to Africa. On the other hand, agricultural products and machinery are other top U.S. exports to the country [29].

In the area of bilateral relations, bilateral engagements between both countries include the U.S.-Nigeria Binational Commission (BNC) which is a mechanism for convening high-level officials for strategic dialogue that was launched in 2010. There is also the U.S.-Nigeria Commercial and Investment Dialogue which aims to enhance bilateral trade and investment, with an initial focus on such issues as infrastructure, agriculture, digital economy, investment, and regulatory reform. On the other hand, the United States maintains an embassy in Abuja and a consulate in Lagos, while the State Department supports American Corners in libraries throughout Nigeria to share information on U.S. culture.

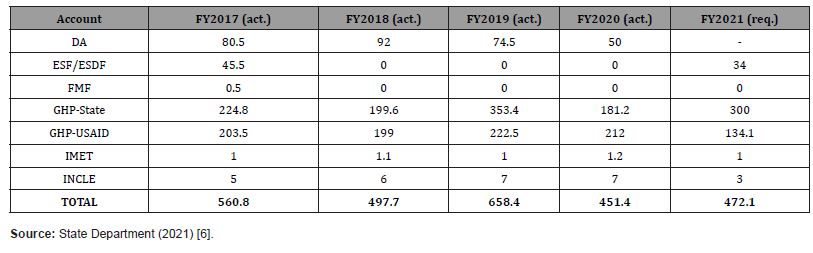

It is on records that Nigerians comprise the largest Africanborn population in the United States, according to U.S. Census data. Equally, Nigeria is a focus country under the President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) as well as Feed the Future, an agriculture development program. U.S. assistance under the Power Africa initiative has supported gas and solar power generation, off-grid energy projects, and regulatory reform in Nigeria [29, 30]. Table 2 shows State Department and USAID-administered assistance to Nigeria from 2017 to 2021.

Table 2:State Department- and USAID-Administered Assistance to Nigeria (selected non-humanitarian accounts, current $ in millions, allocations by year of appropriation)

History and objectives of US security assistance to Nigeria

Available records show that the United States and Nigeria have enjoyed a strong security partnership for more than five decades. The partnership is correlated to one of the U.S. national interests in Nigeria which deals with maintenance of regional peace and security. The other interests, however, are stable democracy with business-friendly environment and free flow of crude oil.

In all ramifications, it can be postulated that the U.S. interest in maintaining zero tolerance for international terrorism gave rise to the establishment of Section 219 of the Immigration and Nationality Act 2001 (as amended) which empowers the U.S. Secretary of State with the approval of the President to designate any violent group(s) found to be involved in terrorist activities outside the United States and whose activities are a threat to the United State security as foreign terrorist organization [5]. In principle, United States security assistance to Nigeria seeks to achieve certain objectives which include to advance global peace. It is in that light that scholars have argued that the US Government has developed and sustained a deep interest in terror-related phenomena across the globe following the events of September 11, 2001. That accounts for the sustained analyses on peace and security within the international system which have sought to give the United States a favorable commentary in her engagements to eliminate global terrorism.

Generally speaking, the U.S. security assistance to Nigeria has sought to bolster peacekeeping capacity, enhance maritime and border security, combat transnational crime, support civilian law enforcement, and strengthen counterterrorism efforts. It therefore cuts across a wide spectrum of security concerns. According to the Department of State [6], from 2016-2020, the Department provided $7.1 million in International Military Education and Training (IMET) funding to the Nigerian military. Nigeria while also being a partner in the Africa Military Education Program (AMEP) equally received $1.1 million to support instructor and/or curriculum development at Nigerian military schools. Specifically in 2016 and 2017, Nigeria received a combined $1.3 million in Foreign Military Financing to support maritime security, military professionalization, and counterterrorism efforts. Being an active member of the Trans- Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership (TSCTP), it received $9.3 million worth of training, equipment, and advisory support for counterterrorism efforts.

According to available records, the United States has $590 million in active government-to-government sales cases with Nigeria under the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) system. Recent and significant sales include up to 12 A-29 Super Tucano aircraft worth $497 million to support Nigerian military operations against Boko Haram and ISIS West Africa and counter illicit trafficking in Nigeria and the Gulf of Guinea. In 2019, the United States also authorized the permanent export of over $127,525 in defense articles to Nigeria via the Direct Commercial Sales process [6].

From 2011 and 2015, Nigeria received $15 million in defense articles granted under the Excess Defense Articles program, to include 24 Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected (MRAP) vehicles and two Hamilton-class U.S. Coast Guard high endurance cutters, the USCGC Chase and the USCGC Gallatin, which entered service in the Nigerian Navy as Thunder and Okpabana in 2011 and 2014, respectively. In 2016, the United States and Nigeria signed an Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement to exchange common types of support, including food, fuel, transportation, ammunition, and equipment. In March 2017, the Department of Defense donated demining and EOD equipment to Nigeria and provided mine action training for Nigeria’s EOD teams at the Nigerian School of Military Engineering [6].

According to Congressional Research Service [31], Nigeria participates in the State Department’s Trans-Sahara Counterterrorism Partnership which is an interagency effort to build regional counterterrorism capabilities and coordination. The country also has benefitted from the provision of U.S. training and equipment to the Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) coalition in the Lake Chad Basin while in addition to funds administered by the State Department, Department of Defence planned roughly $50 million security assistance for Nigeria under its global train and equip program. This falls outside additional assistance which Nigeria received from the United States Department of Defence through regional programs. Instructively, the U.S. has shown its willingness to further assist in some other related categories.

Effects of terrorism in Nigeria and nexus with security assistance

The effects of terrorism in Nigeria are unquantifiable. This could have been possible as Boko Haram, according to Institute for Economics and Peace [8], ranked as the fourth deadliest terrorist group in 2018, and remains the deadliest in Sub-Saharan Africa. For instance, Boko Haram and IS-WA have abducted thousands of civilians, including several thousand children [32]. There have also been three reported mass kidnappings-Boko Haram’s abduction of 276 girls from Chibok (Borno State) in 2014, IS-WA’s abduction of 110 girls from Dapchi (Yobe State) in 2018 and the abduction of 344 boys of Government Science Secondary School Kankara (Katsina State) on December 11, 2020. The sect is equally responsible for 11 suicide bombings, 68 fatalities while the suicide bombings accounted for 6 percent of all terror-related incidents by the terror group in 2019. In fact, Nigeria is currently ranked the third most terrorized countries in the world Knoema [2].

Since its rise in 2009, Boko Haram has been responsible for thousands of deaths throughout the Lake Chad Basin region of West Africa as the salafi-jihadi insurgency has led to 35,000 combatrelated deaths and 18,000 deaths from terrorism since 2011, mainly in Nigeria [10]. Its use of women and children in suicide operations is phenomenal as according to Bigio and Vogelstein [33], two-thirds of Boko Haram suicide attackers are female; of these, one in three are minors.

On the other hand, there were more than 2 million internally displaced persons in Nigeria as of 31 December 2018 largely attributed to the rampage by terrorists in the country. The International Displacement Monitoring Centre [12] informed that there were more than 540, 000 persons displaced by such conflict and violence in 2018 alone. The situation is such that 49 percent of households in the Northeast was experiencing at least one event of the conflict or violence against a household member between 2010 and 2016 [34]. According to United Nations Development Programme [11], the Boko Haram group accounts for large-scale displacement, several incidences of kidnapping, death, and injuries.

In fact, according to World Bank [35], 22 percent of households in the Niger Delta (South-South) region of Nigeria reported at least one terror event between 2010 and 2017, with bandits and criminals accounting for 42 percent of the events. Similarly, 49 percent of households in the North-East had reportedly been victims of a conflict event, more than 66 percent of which were reportedly caused by Boko Haram while 25 percent of households in the North-Central region recorded at least one such event, attributed to attacks by pastoralists (45 percent) and insurgents (21 percent) which left expectedly severe consequences for household welfare. This figure is affirmed by the United Nations Development Programme [11] which hinted that poverty and deprivation manifesting in joblessness and lack of skill by youths supplied the oxygen for radicalization and roles in terrorist conflicts by members of the Boko Haram sect. However, terrorism index in Nigeria decreased to 8.31 in 2019 from 8.60 in 2018, according to Tradingeconomics [36] and revealed by Figure 2.

As the figure reveals, the terrorism index in Nigeria was 9.31 in 2015. It was 8.60 in 2018 and 8.31 in 2019. Its lowest point was in 20002 when it stood at 3.86. The index measures the direct and indirect impact of terrorism, including the effects which it has on lives lost, injuries, property damaged as well as the psychological aftereffects.

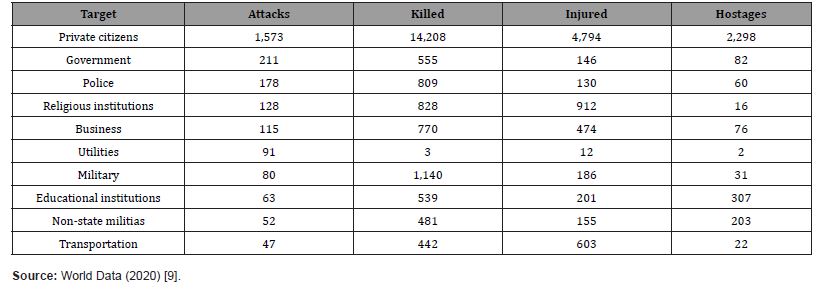

Painting the gory picture of terrorism in Nigeria, World Data [9] hinted that the risk of terrorist attacks in Nigeria over the past years can be classified as extreme high and that worldwide, Nigeria is one of the most dangerous countries with the most and devastating attacks. It was thus its contention that a total number of 2,470 terrorist incidents have been recorded over the past five years in which 17,751 people have been killed and 7,345 injured, among them were 318 suicide attacks. In fact, it further revealed that in 372 incidents, a total of 2,811 people have been kidnapped or taken as hostage. Table 3 presents general list of most frequent attack targets in Nigeria.

Table 3:Most Frequent Attack Targets in Nigeria, 2013-2017

Although the table failed to separate terror incidents from the rest of the other attacks in Nigeria, but it tried to justify the fact known about terrorism to the effect that non-combatant groups (private citizens) are mostly the target and victims of conflicts orchestrated by terrorists. For instance, a total of 14, 208 private citizens were killed in the various attacks in Nigeria between 2013 and 2017. This is, nonetheless, followed by security formations (military and police) where a total of 1,140 and 809 security agents respectively were killed.

Attacks on government-related institutions also featured prominently within the period under review with 211 attacks and 555 deaths. Instructively, abduction of students was high with 307 hostages taken within the period. This is outside the figure of 2,298 private citizens equally taken hostages. Curiously, northern Nigeria is the region most affected by terrorist conflicts and other attacks as Table 4 shows.

Table 4:Nigeria States Most Affected by Attacks, 2013-2017

As the table indicates, northern state of Borno where Boko Haram activities started has witnessed more attacks, number of deaths, injured and hostages than any other state in Nigeria with 981 attacks, 10,044 deaths, 3,275 injured and 1,901 hostages. Two other states in the same northeast zone as Borno - Adamawa and Yobe - followed the trend with 1,247 and 1,233 deaths respectively. The states equally recorded high number of injured and hostages within same period under review. This therefore shows that northern Nigeria and in particular the northeast is the epicenter of violence in the country. Instructively, even though no state in the southeast zone featured among the most attacked states in Nigeria, acts of terrorism has heightened in the area of late.

US security assistance: A game changer or constrained by circumstances?

The assistance notwithstanding, certain conditions within the Nigerian security system have continued to constrain the rendering of major security assistance by the U.S. For instance, the U.S. has not hidden its concerns with human rights abuses by Nigerian security personnel. Such abuses have become notorious and have grabbed international headlines, such that they smear Nigeria’s international image and limit access to international assistance. Specifically in January 2020, former President Trump issued Proclamation 9983 which added Nigeria to the list of countries whose nationals are subject to restrictions on entry to the United States. It was introduced under Executive Order (EO) 13780 (the “Travel Ban”) and Proclamation 9983 particularly stated that Nigeria does not adequately share public-safety and terrorism-related information required for U.S. immigration screening. The action suspended the entry of Nigerian immigrants except as Special Immigrants, subject to waivers and exceptions.

Through the years, various administrations in the country have made attempts to reform the security sector, particularly the police with little or no success. The situation was characterized by waking up almost on a daily basis to the news of extrajudicial executions, inhuman treatment, excessive use of lethal force and crude acts of torture on alleged criminals and innocent citizens by the Nigerian security forces [37]. In particular, during the days that it held sway, the Special Anti-Robbery Squad was notorious for its brutality and fragrant abuse of human rights in the country, such that it was feared for this. It was this notoriety that eventually resulted in protest for its ban as well as its concomitant demise. Such unfortunate records trail other security agencies, including the military.

Obviously, these abuses by the security forces of Nigeria have constrained U.S. security assistance, including counterterrorism aid. In fact, Leahy Laws prohibits U.S. security assistance to security forces credibly accused of gross human rights violations. It is therefore in that light that the Obama Administration in 2014 blocked a transfer of U.S.-manufactured military helicopters from Israel to Nigeria. Also, Obama Administration froze the sale of 12 A-29 Super Tucano attack aircraft to Nigeria in early 2017 after a Nigerian jet struck a camp for displaced people during a bombing raid. The Trump Administration nevertheless revisited that decision, and in late 2017 approved the sale of the aircrafts delivered in 2021.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Nigeria is plagued by terrorism. This has created not just a general sense of insecurity in the country but has become a major factor that hinders her journey towards greatness. Obviously, Nigeria is grossly constrained as far as financial, technological, and military-related capabilities to effectively tackle terrorist conflicts in her territory are concerned. This accounts for the unending and in fact, blossoming nature of the terrorist conflicts. It further explains the rationale behind foreign assistance, particularly from the United States Government in order to enable Nigeria to overcome the debacle.

Nevertheless, the assistance is threatened by certain factors which include gross human rights violations perpetrated by Nigeria’s security forces. Evidence of extra-judicial killings by security agents in Nigeria abound. Efforts to achieve security reform have not succeeded. The resultant effect is that international assistance is often reconsidered or limited. This delays victory over terrorist conflicts in the country. It is not only that the present administration of President Buhari which promised to holistically tackle insecurity has failed to do so, there is little hope that Nigeria will ever record anticipated breakthrough. This brings to fore the need for swift security reform and huge investment in military technology, training, increase in personnel and proper funding for a better anti-terror outcome.

Acknowledgement

None.

Competing Interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Enugu: Great AP Express Publishers Ltd.

References

- Nurudden M (2010) Civil violence and the failure of governance: A reflection on Boko Haram uprising in northern Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Political Science 14(1-2): 39-53.

- Knoema (2020) Global terrorism index.

- Okeke C (2022) Internal insecurity and national development in Nigeria: Problematizing herdsmen and farmers’ conflicts in Anambra State. Asian Research Journal of Arts and Social Sciences 17(1): 1-21.

- Nwanolue B, Ezeamama I, Okeke C (2022) Oil terrorism and politics of environmental protection in Nigeria: The Niger Delta conflict revisited. International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities 11(3): 112-125.

- Ikechukwu U (2016) The United States’ national interests and the fight against Boko Haram terrorism in Nigeria. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 7(3): 478-485.

- United State Department of State (2021) US security cooperation with Nigeria: Fact sheet.

- Okeke C, Omojuwa K (2022) Effects of the practice of federalism in Nigeria on its international image. Scholars Journal of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences 10(6): 299-313.

- Institute for Economics and Peace (2019) Global terrorism index 2019: Measuring the impact of terrorism.

- World Data (2020) Terrorism in Nigeria.

- Warner J, Matfess H (2017) Exploding stereotypes: The unexpected operational and demographic characteristics of Boko Haram’s suicide bombers. Combating Terrorism Centre at West Point.

- United Nations Development Programme (2018) National human development report: Achieving human development in north east Nigeria. New York: UNDP.

- International Displacement Monitoring Centre (2019) Nigeria: International displacement monitoring centre.

- Adedire S (2016) Combating terrorism and insurgency in Nigeria: An international collaborations against Boko Haram. Fountain Journal of Management and Social Sciences 5(1): 67-74.

- Onuoha J (2008) Beyond diplomacy: Contemporary issues in international relations. Enugu: Great AP Express Publishers Ltd.

- Olisa M et al (2016) Government and politics for schools and colleges. Onitsha: Africana First Publishers Plc.

- Onuoha F (2013) Terrorism. In H Saliu, F Aremu (eds). Introduction to International Relations. Ibadan: College Press and Publishers Limited.

- Cronin A (2004) Behind the curve: Globalization and international terrorism. In Air War College. National security and decision making: Part 1 of international security studies. Alabama: Air University, USA.

- Toros H (2008) We don’t negotiate with terrorists: Legitimacy and complexity in terrorist conflicts. Security Dialogue 39(4): 407-426.

- KidNai S (2002) US and international terrorism. In V Grover (ed). Encyclopedia of International Terrorism, vol 2. New Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications Limited.

- Radu M (2002) Terrorism after the Cold War: Trends and challenges. Orbis, A Journal of World Affairs 46(2): 275-287.

- Igwe O (2007) Politics and globe dictionary. Enugu: Keny and Brothers Enterprise.

- Oyeshola D (2005) Conflict and context of conflict resolution. Ile-Ife: Obafemi Awolowo University Press.

- Oromareghake P (2013) Youth restiveness and insecurity in Niger Delta: A focus on Delta State. Global Journal of Human Social Science 13(3): 46-53.

- Husted T, Blanchard L (2020) Nigeria: Current issues and U.S. policy. Congressional Research Service.

- Campbell J (2014) Boko Haram: Origins, challenges and responses.

- Nagy T (2018) The enduring partnership between the United States and Nigeria.

- United States International Development Agency (2019) Lake Chad Basin-complex emergency, fact Sheet: Washington DC: USAID.

- United States Department of Commerce (2020) International trade and investment: Country factsheets. Washington DC: USDC.

- United States Congressional Service (2014) Human rights vetting: Nigeria and beyond. Washington, DC: US Congress.

- United States International Development Agency (2020) Nigeria: Power Africa fact sheet. Washington, DC: USAID.

- Congressional Research Service (2020) Nigeria: Current issues and US policy.

- Hinshaw D, Parkinson J (2016) The 10, 000 kidnapped boys of Boko Haram.

- Bigio J, Vogelstein R (2019) Women and terrorism: Hidden threats, forgotten partners. Council on Foreign Relations.

- Azad M (2018) Conflict and violence in Nigeria: Results from the north east, north central and south south zones (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

- World Bank (2019) Nigeria economic update: Jumpstarting inclusive growth, unlocking the productive potential of Nigeria’s people and resource endowments. Nigeria: World Bank Group.

- Tradingeconomics (2020) Terrorism index in Nigeria.

- Obiakor N (2021) Impunity in Nigeria’s security forces: A case of the Special Armed Robbery Squad, 1992-2020. Journal of African Studies and Sustainable Development 4(3): 121-139.

-

Okeke, Christian Chidi* and Ezeamama, Ifeyinwa G. Trends and Strategies of International Cooperation Against Terror: Terrorist Conflicts and United States’ Security Assistance in Nigeria Revisited. Iris On J of Arts & Soc Sci . 1(4): 2023. IOJASS.MS.ID.000516.

-

Nigerian military, Political contradictions, Social, Economic, Foreign Military Sales

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.