Research Article

Research Article

Self-Concept and Lesbian Tendencies Among Secondary School Girls in Osun State: Implications for Sexual Counseling

Ilugbami Joseph Olanrewaju*

Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, Owo-Rector’s Office, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria

Ilugbami Joseph Olanrewaju, Rufus Giwa Polytechnic, Owo-Rector’s Office, Owo, Ondo State, Nigeria

Received Date: February 06, 2023; Published Date: February 15, 2023

Abstract

There is a need for effective sexual orientation and counselling for girls in Nigeria’s secondary schools. This study examines self-concept and lesbian tendencies of girls in secondary schools in Osun State for the purpose of achieving appropriate sexual orientation and counselling. Null hypotheses were formulated following the research design. The research population covers 1,000 girls in secondary schools across the 50 public and private secondary schools in Osun State. 873 respondents were later selected using a multistage sampling technique. “Self-Concept and Lesbian tendencies Questionnaire (SCLTQ)” with Cronbach reliability of between 0.74 and 0.86 estimates were the instrument used for data collection. Descriptive statistics were employed to analyse the collected data, while the null hypotheses were all tested using inferential statistics on SPSS version 23. The study found that the level of lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools of Osun State is low; there is a positive and significant relationship between self-concept and lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools (R= 0.534; p < 0.05). Based on these findings, recommendations were suggested with counselling implications for appropriate sexual orientation.

Keywords:Self-concept; Lesbian tendencies; Counselling; Sexual orientation

Introduction

Self-concept is an individual’s perception of themselves, including their beliefs, attitudes, and values. It is a key aspect of persons’ identity and is impactful on the mental and emotional well-being of an individual [1]. Lesbian tendencies refer to a woman’s romantic and/or sexual attraction towards other women. Self-concept has been shown in different researches that it is an avenue for the development of lesbian tendencies. Girls who have a positive self-concept may be more likely to explore and accept their sexual orientations, including those that do not conform to societal expectations (National Association of School Psychologists) [2]. Conversely, girls with negative self-concepts may feel anxious to conform to societal expectations and may be less likely to explore or accept their non-heterosexual orientations [3].

Adamczyk (2017) [4] is of the opinion that sexual orientation is a multi-faceted and complex aspect of identity that may be predisposed by varying factors, such as societal expectations, family, self-concept, and culture. Therefore, it is essential to understand that self-concept is not the only most significant factor influencing the acceptance of lesbian tendencies [3]. School enhances the creation of an inclusive and safe environment for all students, regardless of their sexual orientation. This includes providing appropriate and accurate information about sexual orientation and promoting acceptance and understanding of diversity [4].

Senior secondary school education in Osun State is an essential stage of a student’s education. It is the final stage of secondary education after junior secondary education, and before tertiary education. The secondary school education in Osun State usually lasts for three years, with students typically entering the system at age 15 or 16. The curriculum is designed to prepare students for higher education and to develop the skills and knowledge necessary for success in the tertiary institution [5].

In Osun State, secondary schools are divided into two main categories: government-owned and private-owned schools. Privateowned schools are funded and managed by private individuals or organizations and are mostly situated in urban areas. Governmentowned schools are owned and operated by the government and are situated in both urban and rural areas. Both types of schools offer a similar curriculum and follow the same national educational policies and guidelines [5].

According to Uzoeshi (1996) [6], counselling enhances the pertinent role of supporting and equipping students with selfconcept and sexual orientations in secondary schools. It provides a safe space for students to explore their identities and work through any challenges they may be facing. Counsellors should be trained to work with students on these issues in a non-judgmental and sensitive manner and to provide appropriate referrals and resources as needed (National association of school psychologists) [2]. Taiwo et al. (2017) [5] recommended in their study that schools should come up with an enabling environment for counsellors to provide appropriate support for students in the areas of selfconcept and sexual orientations.

Self-concept entails a wide range of emotional, behavioural, and cognitive aspects of human self-perception, and it plays a crucial role in shaping the ideology of an individual and the world at large [7]. It is the attitude and belief of individuals about themselves. In the context of sexual orientation, self-concept can affect how individuals understand and accept their sexual identity [8]. For instance, [1] noted that there is high tendency that a person with positive self-concept will be willing to accept sexual orientation and be more comfortable expressing their identity. Conversely, a person with negative self-concept may find it difficult to accept sexual orientation and may experience feelings of fear or shame.

Self-concept is also closely related to self-esteem, which is the overall evaluation of one’s self-worth [9]. Individuals with high selfesteem tend to have a positive self-concept and view themselves in a positive light, while individuals with low self-esteem tend to have a negative self-concept and view themselves in a negative light. Selfesteem can be influenced by various factors, including childhood experiences, socialization, and cultural norms [10].

According to Caglar (2009) [11], self-concept is not fixed and it can change over time. This means that an individual’s self-concept can improve or worsen depending on their experiences and interactions with others. For example, a positive experience, such as receiving a compliment or achieving a personal goal, can boost self-concept, while a negative experience, such as facing rejection or failing a test, can decrease self-concept [12]. Hossain, et al. (2019) [12] went ahead to explain that it is also important to note that self-concept can be influenced by cultural and societal factors. For example, in a culture that promotes traditional gender roles, an individual who deviates from these roles may experience a negative self-concept and struggle with their sexual orientation.

Counsellors should support students with positive self-concept, by initiating individual and group counselling sessions, facilitating support groups, and working with school administrators to create a safe and inclusive environment for all pupils [13]. Additionally, they can guide teachers on how to support pupils with different sexual orientations and how to create a positive and accepting classroom environment [7,14, 15]. Concerning the development of sexual orientation among pupils in secondary schools in Osun State, selfconcept is particularly relevant.

Lesbian tendencies refer to an individual’s attraction to or interest in other individuals of the same gender. This can include romantic, sexual, and emotional attractions. The term “lesbianism” is typically used to describe female-to-female attraction, and it is one aspect of female homosexuality [16]. According to Dahl & Galliher (2010) [17], it is important to note that sexual orientation, including lesbian tendencies, can develop and evolve and is not something that can be changed. It is a normal and natural aspect of human sexuality, and individuals who experience lesbian tendencies should be accepted and treated with dignity and respect.

Nonetheless, in some cultures and societies, lesbian tendencies may not be accepted or understood, and individuals who experience them may face discrimination, stigma, and prejudice. This can have a negative impact on their self-concept and overall well-being [18]. Therefore, it is important for schools and communities to promote acceptance and understanding of all sexual orientations, including lesbian tendencies, and to provide support to individuals who experience them. This can include providing education and resources, creating safe and inclusive environments, and addressing negative attitudes and stereotypes [18, 19].

According to Sybil (2019) [20], Hossain et al. (2019) [12], and Meyer (2003) [21] in the cases of lesbian tendencies, societal attitudes and messages about homosexuality can impact an individual’s self-concept and the expression of their sexual orientation. In some cultures and societies, there may be negative attitudes and stereotypes associated with homosexuality, leading to discrimination and stigma. This can make it difficult for individuals who experience lesbian tendencies to accept and embrace their sexuality and can negatively impact their self-concept.

Conversely, individuals are more likely to develop a positive selfconcept and feel confident in expressing their sexual orientation in supportive environments. This can lead to better mental health outcomes and a more fulfilling life experience [12]. The aim of this study is to determine self-concept and lesbian tendencies among secondary school girls in Osun State. The specific objectives are to examine the level of lesbian tendencies among girls; to examine the relationship between the two concepts of lesbian tendencies and self-concept; and to examine the relationship between the two concepts of sexual orientation and counselling.

Methodology

The study areas are Ilesa and Osogbo in the Osun State of Nigeria. The ex-post facto research design was employed for this study. From the study population of 1000 secondary school girls, a sample of 50 secondary school girls was selected through the simple random sampling technique. The Self-concept and Acceptance of Lesbianism Tendency Questionnaire (SALTQ), comprising two sections were employed for data collection. The first section provided demographic data while the second section entails 30 items on the variables of the study on a four-point Likert Scale of strongly disagreed (SD), Disagreed (D), Agreed (A), and Strongly Agreed (SA). The instrument was face-validated by submitting it to one expert in guidance and counselling and one in test and measurement for scrutiny. The instrument was subjected to a trial test using 14 students selected from two secondary schools in the Local Government. These were not part of the study participants, but they had similar characteristics to them. A Cronbach alpha reliability estimate of between 0.74 and 0.86 for the instrument was established; the instrument was deemed reliable as affirmed by Adeniran (2019) [22] that a Cronbach alpha of 0.7 and above is suitable.

The instruments for data analysis were one sample or population t-test and an independent t-test. To be able to use the independent t-test, the respondents for this research were divided into two groups viz high and low based on whether they scored above the average score or below the average score. From the weighting of the instrument, the highest expected score and lowest expected score by a respondent are 20 and 5 respectively.

The independent variables were measured by five items each. The average score was derived as follows:

[1*5] + [2*5] + [3*5] + [4*5]

= 5+10+15+20 =50.

50 divided by 5 (items used to measure the independent variables) =10.

Therefore, a respondent that scored 9 and below was categorized as low while one that scored 10 and above was categorized as high.

The following null hypotheses were tested in the course of the study:

H01: The level of lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools of Osun State is high; and

H02: There is no significant relationship between self-concept and lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools in Osun State.

Results

Table 1:One sample t-test.

The results in Table 1 indicate that the mean rating of lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools in Osun State is 21.44 which is below the test value of 26 with a mean difference of 3.779. The significance level (p-value: 0.000< 0.05) at 872 degrees of freedom shows numerical evidence to reject the null hypothesis which states that the level of lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools of Osun State is high. Hence, the alternate hypothesis which states that the level of lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools of Osun State is low will be affirmed.

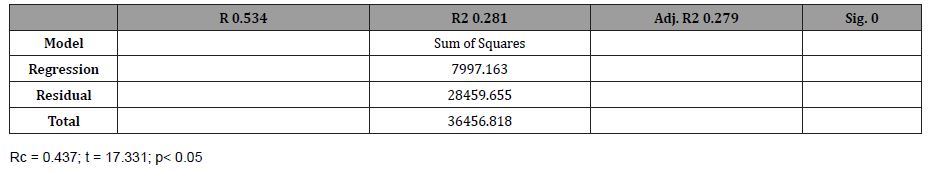

Regarding the second hypothesis which states that there is no significant relationship between self-concept and lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools in Osun State, simple linear regression analysis was performed at a 0.05 significant level. The results of the analysis are presented in Table 2.

Table 2:Linear regression.

The result presented in Table 2 shows (R = 0.534, 0.000< 0.05) gives numerical evidence to reject the null hypothesis which states that there is no positive and significant relationship between physical self-concept and lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools in Osun State. Hence, the alternate hypothesis which states that there is no positive and significant relationship between physical self-concept and lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools in Osun State will be affirmed.

The results in Table 2 also showed that physical self-concept could be held accountable for 28.1% of the total variance in lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools. By implication, the remaining 71.9% could be explained by other independent variables not included in the model. The regression coefficient (Rc) indicates that other things being equal, a unit increase in the standard deviation of physical self-concept will lead to a 0.437 increase in the standard deviation of lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools in Osun State.

Discussion of Findings

This study established through its first major findings that the level of lesbian tendencies among secondary school girls in Osun State is low. This finding is unsurprising because the notion of lesbianism is a strange practice in Osun State. The government’s sanction of 14 years imprisonment for anybody identified as a lesbian may also be the reason such practice is low among girls in secondary schools. Another reason may be the low level of awareness of the concept of lesbianism in secondary schools.

This finding disagrees with some studies conducted by Canali et al., (2014) [23], Rosario et al., (2006) [24], Henderson, Simoni and Lehavot (2010) [25], which found a high practice of lesbian tendencies among ladies, and that both lesbians and heterosexual women possess a similar constellation of factors. The difference in the results may have been due to differences in the study areas as almost all these studies were conducted in foreign countries. This finding, Nonetheless, agrees with the results of Seigler (2015) [8] which was conducted in Nigeria and found that the rate of lesbianism is low, especially after the signing of the 14 years imprisonment act. Nonetheless, the study showed further that the acceptance of lesbians, gays, and bisexuals people in Nigeria is gradually increasing.

Furthermore, it was discovered that there is a positive significant relationship between physical self-concept and lesbian tendencies among girls in Osun State secondary schools. Physical self-concept could be held accountable for 28.1% of the total variance in lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools. This result may have appeared this way since an individual’s perception of herself may affect her disposition and the things she accepts. For instance, a person with a highly positive physical selfconcept may see herself as being too beautiful to be used by a fellow woman for sexual satisfaction. Some ladies that view themselves as sexually over-active, may forgo having sexual intercourse with men if they believe that cannot satisfy them and may opt to go for female sexual partners.

This finding agrees with the findings of Giuliano and Gomillion (2011) [26] which established a significant relationship (R: 0.76) between self-concept and homosexual identity (gay, lesbian, and bisexual), but disagree with the findings of Lynch (2005) which revealed that there is no significant relationship between physical self-concept and level of involvement in lesbianism, gay, and transgender activities. Also, it does not agree with the findings of Eames, DClinPsy and DClinPsy (2016) [27] which found that there is no significant relationship between self-concept and attachment to lesbianism.

Conclusion

Cultural norms and religious beliefs can play a significant role in shaping self-concept, particularly concerning sexual orientation. In Nigeria, homosexuality is widely stigmatized and many pupils may feel pressure to conform to traditional gender roles and heteronormative expectations. This can make it difficult for pupils who have lesbian tendencies to explore and accept their sexual orientation, and may contribute to a negative self-concept [28].

Moreover, the education system in Osun State is facing several challenges, including inadequate funding, poor infrastructure, and a lack of qualified teachers. These challenges can make it difficult for pupils to develop a positive self-concept and understand their sexual orientation. For example, poor academic performance can lead to feelings of inadequacy and low self-esteem, which can make it difficult for pupils to explore and accept their sexual orientation. Similarly, a lack of support from teachers and peers can lead to feelings of isolation and rejection, which can also have a negative impact on the development of self-concept [17].

Although the level of lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools of Osun State is low and the fact that there is no positive and significant relationship between physical self-concept and lesbian tendencies among girls in secondary schools in Osun State, counsellors can still help pupils navigate the challenges that may arise as a result of their sexual orientation, such as discrimination and stigmatization. This can include providing support in dealing with harassment, bullying, and violence, and helping individuals find ways to connect with others who have similar experiences [29-35].

It is important for counsellors to be knowledgeable about the cultural and societal context of lesbian tendencies and to be aware of any legal and policy implications related to sexual orientation. This can include being familiar with the laws and policies related to (Lesbian Gay bisexual, and transgender) LGBT rights, as well as being aware of any cultural and religious norms that may impact an individual’s experiences and beliefs related to their sexual orientation.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Trautwein U, Ludtke O, Marsh HW, Nagy G (2009) Within-school social comparison: How students perceive the standing of their class predictions and academic self-concept. Journal of Educational Psychology 101(4): 853-866.

- National association of school psychologists (2003) Adolescent Medicineand Health 20(3): 275-282.

- Uzoeshi KC (2019) Lesbianism: causes and effects.

- Adamczyk A (2017) Cross-national public opinion about homosexuality: Examining attitudes across the globe. The University of California Press pp. 3-7.

- Taiwo P, Bamidele B R, Agbana RD (2017) Knowledge and effect of sex education on adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Osun State, Nigeria. Developing Country Studies 7(9).

- Uzoeshi KC (1996) Masturbation: Causes and Effects, Implication for Counselling. Port Harcourt Journal of Psychology and Counselling 3: 1-5

- Azubuko AH (2019) Self-concept and lesbian tendencies among senior secondary school girls in Uvwie L.G.A. of Delta State. An unpublished undergraduate thesis, University of Calabar.

- Seigler C (2015) Acceptance of lesbian, gay and bisexual people increasing slowly in Nigeria.

- Heinz JE, Horn S (2014) Do adolescent’s evaluations of exclusion differ based on gender expression and sexual orientation?Journal of Social Issue v. 70(1).

- Purvis A (2017) Coming-out, discrimination, and self-esteem as predictors of anxiety and depression in the lesbian community. PhD thesis submitted to Walden University College of Social and Behavioural Sciences.

- Caglar E (2009) Similarities and differences in the physical self-concept of males and females during late adolescence and early adulthood. Adolescence 44(174): 407-419.

- Hossain F, Ferreira N (2019) Impact of social context on the self-concept of gay and lesbian youth: A systematic review. Global Psychiatry 2(1): 1-28.

- Edobor JO, Ekechukwu R (2015) Factors influencing lesbianism among female students in Rivers State University of Education, Port Harcourt. International Journal of Academic Research and Reflection 3(6): 43-51.

- Duruamaku-Dim JU (2019) Self-concept and lesbian tendencies of girls in senior secondary schools in Cross River State: Counselling implications for appropriate sexual orientation. Calabar Counsellor 8(1): 111-124.

- Arop FO, Madukwe EC, Owan VJ (2019) Adolescent’s perception management and attitudes towards sex education in secondary schools of Cross River State, Nigeria. International Journal of Management Sciences and Business Research 8(3): 32-38.

- Russell ST, Toomey C, Diaz RM (2014) Being out at school: The implications for school victimization and young adult adjustment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84(6): 635-643.

- Dahl A, Galliher R (2010) Sexual minority young adult religiosity, sexual orientation conflict, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health 14(4): 271-290.

- Harper G (2007) What is good about being gay? Perspectives from youth. Journal of Lesbianism, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth (LGBT) 9(1): 22-41.

- Grossman A (1997) Growing up with a spoiled identity. Journal of Gap and Lesbian Social Services 6(3): 45-56.

- Sybil S (2019) Female homosexuality (lesbianism) and bisexuality.

- Meyer IH (2003) Social stress, prejudice and mental health in LGB populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 129(5): 674-697.

- Adeniran AO (2019) Application of Likert Scale’s Type and Cronbach’s Alpha Analysis in an Airport Perception Study. Scholar Journal of Applied Science Research 2(4): 01-05.

- Canali TJ, Oliveira SMS, Reduit DM, Vinholes DB, Feldens VP (2014) Evaluation of self-esteem among homosexuals in the southern region of the state of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 19(11): 4569-4576.

- Rosario M, Schrimshaw EW, Hunter J, Braun L (2006) Sexual Identity Development among LGBT Youths: Consistency and Change Over Time. Journal of Sexuality Research 43(1): 46-58.

- Henderson AW, Lehavot K,Simoni JM (2010) Ecological models of sexual satisfaction among lesbian/bisexual and heterosexual women. Arch Sex Behav 38(1): 50-65.

- Gomillion SC, Giuliano T (2011) The influence of media role models on gay, lesbian, and bisexual identity. Journal of Homosexuality 58(3): 330-354.

- DClinPsy KB, Eames C, DClinPsy PW (2016) The role of self-compassion in the well-being of self-identifying gay men. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Mental Health 10(1): 1-20.

- Liddle BJ, Schuck KD (2001) Religious Conflicts Experienced by Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Psychotherapy 5(2): 63-82.

- Campbell J (1990) Self-esteem and clarity of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59(3): 538-549.

- Garofalo R, Wolf RC, Kessel S, Palfrey J, Durant RH (1998) The association between health risk behaviours and sexual orientation among a school-based sample of adolescents. Paediatrics 101(5): 895-902.

- Henry MM (2013) Coming out: Implications for self-esteem and depression in gay and lesbian individuals. M.S. Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Science. Humboldt State University.

- Hershberger S, D’Augelli A (1995) The impact of victimization on the mental health and suicidality of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Developmental Psychology 31(1): 65-74.

- Osamanga F (2017) The impact of self-esteem on attitudes towards homosexuality. European Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies 3(3): 171-176.

- Snapp S, Watson R, Russel S, Diaz R, Ryan C (2015) Social support networks for LGBT young adults: Low-cost strategies for positive adjustment. Family Relations 64(3): 420-430.

- Woodford MR, Paceley MS, Kulick A, Hong JS (2015) The LGBQ Social Climate Matters: Protests, Placards and Polices and Psychological Well-Being Among (Lesbian Gay bisexual, transgender) LGBT, Emerging Adults. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services 27(1): 116-141.

-

Ilugbami Joseph Olanrewaju*. Self-Concept and Lesbian Tendencies Among Secondary School Girls in Osun State: Implications for Sexual Counseling. On J of Arts & Soc Sci. 1(1): 2023. IOJASS.MS.ID.000505.

-

Cultural and societal context, Sexual orientation, Physical self-concept, Violence, Harassment, Heteronormative expectations, Secondary schools, Alternate hypothesis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.