Research Article

Research Article

Local Communities’ Participation in Formulation and Management of Payments of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): A Case Study of Mining Communities in Birim North District, Ghana

Julius Kwasi Ofori, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology Ghana.

Received Date: February 24, 2023; Published Date: April 03, 2023

Abstract

In exploring the nexus of CSR and its influence on local development, a discussion on community engagements and participation becomes eminent. The impacts of these CSR payments on communities as well as the companies over the years have been diverse but whether beneficiary communities are involved in the CSR payments is a subject to be looked at. It is in line with this, that the study sought to look at local community’s participation in the formulation and management of payments of Corporate Social Responsibility in Birim North District in the Eastern Region of Ghana. The study used both quantitative and qualitative approaches to gather the data. A simple random sampling technique was used to select respondents and a questionnaire survey conducted to obtain the quantitative data. Chi square tests and cross tabulation analysis were employed in the data analysis. From data gathered and analyzed, the study revealed that a more significant number of beneficiary communities and formal institutions were involved in the formulation of CSR payments. Again, evidence on levels of participation suggested that though the majority of respondents were engaged at various levels of CSR formulation, it has been shown that little participation took place at the decision-making and implementation stages. There was a significant relationship between the communities and levels of participation. Findings gathered from the study further revealed that the management of the completed CSR payments was a collaborative effort among Akyem Newmont mining company, the District Assembly and the beneficiary communities with the view to ensure the sustainable use of these facilities.

Keywords:CSR payments, Formulation, Participation, Management, Community, Sustainability

Introduction

Studies on development practices have identified that sustainable community development needs to be founded on the highest level of participation of the intended beneficiaries [1]. Again, literature covering the community development within the context of the extractive industry has progressed from a discussion on corporate social responsibility to more recently on a focus of social license to operate [1]. In exploring the nexus of CSR and its influence on local development, a discussion on community engagements and participation becomes eminent. Maconachie and Hilson [2] highlight the gap between corporate programmes and local needs and further asserts that programmes without appropriate mechanisms to integrate grass root participation will struggle to meet local needs.

Frynas [3] in addressing the reasons CSR initiatives fail to meet the needs of communities identifies lack of participation in community development projects, a “top-down” orientation that characterizes the formulation of CSR initiatives and the lack of broad consultation. Hence, although the promises and investment in CSR may be quite significant, its impacts are less obvious. In this regard, Macdonald [1] suggests that for the substantial investment in CSR to yield tangible benefits, the process must embrace indigenous authored and managed programs with community members at the center. The ability of CSR to stimulate sustainable development from the extractive sector has come under scrutiny, as there is evidence of a gap between the stated intentions of companies and their actual conduct and impact in the real world [3].

In Ghana, corporate social responsibility is growing in the mining industry, with a significantly greater section of the gold mining industry engaged in some form of CSR [4]. To further underscore the commitment of mining corporations to CSR, $24 million as of 2011 had been invested in the sector [5]. However, despite the strides of mining corporations to incorporate CSR there is a heightening sense of resentment among Ghanaians towards the mining industry [6]; Standing and Hilson, 2013). Indigenes of mining communities have often felt exploited by mining corporations [7-8] because the required benefits of mining have not been handed back to the community [9]. Also, such discontentment among citizens even in the face of the desire to seek community development through CSR is explained by lopsided engagements with powerful minority groups such as chiefs and opinion leaders whose approval are patronised in exchange for financial benefits [7]. Such unethical practices only serve to heighten acrimonious sentiments among citizens within mining-affected areas.

Furthermore, Jenkins and Obara [10] in a study of CSR practices of two multinational mining corporations in the Western Region of Ghana, an area which accounts for fifty percent of the country’s gold mines, revealed that CSR practices rather engendered a sense of dependency among inhabitants which tends to undermine concerns for sustainability of livelihoods. They further conclude this situation arises, among other reasons, as a result of inadequate community engagements and broad-based consultations. Frynas (2005) underscores this point with the observation that where engagement with the communities takes place, it is rather inadequate and most often not all-inclusive. Hence, a major limitation to the effectiveness of CSR, as Frynas [3] points out, is the failure to involve the affected communities in CSR initiatives. Frynas [3] recommends that communities must be engaged and enabled to continuously participate in community development projects rather than being passive beneficiaries of initiatives from mining companies. The situation is further exacerbated by the absence of a national policy framework that guides the conduct of CSR.

The Mineral Commission CSR guidelines (2012) provide a loose framework that guides CSR in the mining sector in Ghana. The guidelines mainly consist of voluntary benchmarks for the conduct of CSR [11]. The Minerals Commission guidelines in relation to stakeholder engagements stipulate that “mining companies operating in Ghana should implement effective and transparent engagements, communication and independently verified reporting arrangements with their stakeholders” [12]. Further, in relation to community development, the guideline states that “mining companies operating in Ghana should contribute to the social, economic and institutional development of the community in which they operate” (Minerals Commission guidelines as cited in Andrews, p.13 [11]. This therefore leaves room for ambiguity as to the extent to which communities must be engaged in the formulation and implementation of CSR that ensures sustainable development; places the incorporation of community inputs at the discretion of mining corporations. That notwithstanding, mining corporations are resolute in their commitment to contribute to community development through CSR and have adopted CSR to enhance their image and ensure sustainable and successful operations [4]. Literature provides evidence of CSR practices in the mining industry; however, the bright prospects of CSR is not as obvious. This speaks volumes about the fact that there is the need for further insight into corporate social responsibility within the Ghanaian mining industry to ensure sustainable development [6,13].

It is in this light that this research seeks to contribute to the growing body of knowledge and fill the gaps in research in the Ghanaian mining industry by exploring the local communities’ participation in the formulation and management of CSR programs in the Birim North districts in the Eastern region.

Literature Review

Corporate social responsibility is a growing, large-scale initiative in the Ghana’s mining industry [4]. Mining organizations cannot reach the GOLD ranking without a formal corporate social responsibility policy [14]. As of the year 2011, the total corporate social responsibility expenditure was $24 million [5]. The majority of gold mining firms are engaged in some level of corporate social responsibility, which Sadik (2013) [4] attributed to an attempt to mitigate Ghanaians’ negative perceptions of the mining industry. Mining organizations should seek possible ways of improving the livelihood of individuals living in mining communities and also offer better ways of carrying out their activities sustainably [15].

According to Armah et al., [7] and Preuss et al., [16], Ghana’s gold mining industry lacks a benchmark for corporate social responsibility on the legislative level, which may contribute to the inconsistency in socially responsible business activities. Standing and Hilson [5] reports that although the mining industry in Ghana as a system must provide positive benefits to the community, in reality, corruption and mismanagement led to diminished efficacy of policies requiring companies to distribute a proportion of mining rents to local authorities and traditional leaders.

In addition, Lawson and Bentil [6] and Standing and Hilson [5] recommended that through increased transparency, social accountability, and changes to the distribution system, corruption, and mismanagement could be reduced drastically. Specifically, well-designed corporate social responsibility that directly targeted improvements for citizens can improve public perceptions of the gold mining in Ghana [6]. Although studies over the past four decades have seen increased scholarly attention on participation in community development, it has only recently gained much prominence [1]. Community participation refers to the process by which individuals are equipped to become actively and effectively involved in identifying issues of concern to them, in terms of decision-making about the factors that affect their lives in formulating and implementing polices, in planning and delivering services and in acting to achieve change (Doherty, 2002 as cited in Calistus et al. 2006 p.71). Muangi [17] further stated that participation may take various forms, ranging from contributions in terms of cash and labour to consultancy services, behavioral changes, administration involvement, management, and decisionmaking. Community participation therefore goes beyond merely satisfying statutory requirements by organizations but represents a means through which community needs and interests can be identified and served [18].

According to Young [19] true participation is a means of a person’s ability to engage in decision-making through expression of their opinions and perspectives on issues. Thus, people should have a direct involvement in matters that concern them and their actions. Fraser [10] notes that equity in participation can be denied, and the extent of inclusion or otherwise is determined by the social structures in place. Again, Mulwa [20] emphasizes the essence of participation, expressing the view that unless people are major players in the activities that impact their lives, the effect of interventions would either be negative or insignificant. Blau cited In Chitere [21] notes that participating in development activities is a goal-driven phenomenon, which is based on the attainment of benefits. People are therefore likely to participate in projects that have the potential to deliver benefits to them. In identifying the relevance of participation, Chamala [22] emphasizes that the involvement and engagement of stakeholders and community players at all levels from national to local ensures efficiency in sustainable resource management. Participation therefore improves project effectiveness through community ownership of development effort and aids decision-making [23]. Kelly [24] views participation as a means to facilitate learning, which in turn influences behavioral change. In the view of Gow and Vansant [25] the relevance of participation can be summed up in four observations, namely;

i. People react best to problems they consider most essential;

ii. Local people tend to make efficient decisions in the context of their circumstances and environment;

iii. Voluntariness in terms of provision of labour, time, money, and materials to a project play a significant role in avoiding dependency and passiveness;

iv. The extent of local influence over development activities such as control over amount, quality, and benefits of development activities has a positive bearing on the sustainability of the project.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework of this study is hinged on Pretty et al (1995) typology of participation. This typology explains the extent of stakeholder participation and how much real power stakeholders have to determine the process and outcomes. Pretty et al (1995) typology of participation is based on seven stages namely;

i. Manipulative participation,

ii. Passive participation,

iii. Participation by consultation,

iv. Participating for material incentives,

v. Functional participation,

vi. Interactive participation,

vii. Self-mobilization.

For manipulative participation, participation is by pretense involving nominated representatives with little or no power. Interaction between local stakeholders and institutions of management is mostly limited or non-existent. Passive participation involves unilateral decisions without proper regard for people’s views. Participation here mainly involves people being informed about what has already been decided. The decision making process is in the domain of professionals. In the case of participation by consultation, problem identification and the process of information gathering is defined and informed by external agents. Such agents also have control over data analysis. The decision-making process is exclusive to professionals who are under no obligation to adopt people’s views and the people have no or little influence over proceedings.

Participating for material incentives is where participation is motivated by the promise of material incentives. Example is the provision of labour in return for cash, or other incentives. On the other hand, people are less motivated to participate if such incentives are not forthcoming. Decisions remain exclusive to management. With functional participation, external agents embrace participation to meet predetermined objectives. Participation is regarded as an opportunity to achieve project goals and save cost.

The nature of this type of participation may be characterized by interaction and shared decision making. However, this type of participation is utilized only after the important decisions have been determined by external agents. Local people are involved only to realizing external goals. For interactive participation, participation is sought in joint analysis, formulation of action plans and the development and enhancing the capacity of local institutions. Participation is viewed as a right not just as an external obligation. Finally, self-mobilization occurs by local people acting independently of external institutions to effect systemic changes. It involves a primary transfer of power and responsibility for resources.

Methodology

The study was conducted in Birim North District of the eastern region of Ghana in the following communities namely; Ntronang, Afosu, Adausena, Obohemaa, Mamanso, Old Abirem, Amanfrom, New Abirem, Yayaso and Hweakwae (Figure 1).

Figure 1:A map of Ghana showing Areas of operations of Newmont Ghana Ltd and the study communities (Ntronang, Afosu, Adausena, Obohemaa, Mamanso, Old Abirem, Amanfrom, New Abirem, Yayaso and Hweakwae).

This District was carved out from the former Birim District Council in 1987. It shares borders with Kwahu West Municipal to the North, west by Asante Akyem South and Adansi South Districts; south by Akyemansa District, and to the east by Atiwa and Kwaebibirem Districts. The district has a population of 78,907 which represents 3.0 percent of the region’s total population (GSS, 2010). The district has large deposits of gold in the Southern part around Ajenjua Bepo surrounded by Ntronang, Afosu, Adausena, New Abirem, Yayaso and Hweakwae communities. Annually, it is estimated that an amount of 500,000oz (ca. 19 t) of gold will be mined over the next 15 years with an 8.5Mtpa processing plan (ERCC,2017). The district is endowed with a wide variety of flora and fauna and is home to ten well managed forest reserves. The Birim and Pra Rivers have their confluence located near Otwereso. Hilly areas sometimes reach an altitude of over 61 meters. The Pra and Birim Rivers are the two main rivers in the district. River Pra serves as a boundary between the district and two other Districts in Ashanti region, whilst the Birim River serves as a boundary to the southern District.

A mixed method was employed for the study, since the research examines community participation in influencing the effectiveness of CSR payments. The mixed approach has the benefit of eliminating the biases inherent in other methods and offers triangulation of seeking convergence across qualitative and quantitative methods. To address the research questions, the case study approach was used drawing on insights from community stakeholders of Birim North and the Newmont mining company since it focused on the mining affected communities of the Birim North district whose livelihoods have been impacted by mining operations and seeks to build insights into their involvement in influencing CSR payments as well as their level of satisfaction with the outcomes of CSR payments.

Survey research design was used to discover the interrelationship between variables. Questionnaires were used to gather information from respondents, and semi-structured interviews were conducted for key stakeholders. The respondents for the study included all the ten (10) beneficiary communities, the District Assembly, officials of the CSR department of Akyem Newmont and traditional authorities. Two hundred (200) respondents were selected from the ten (10) beneficiary communities using simple random sampling for the quantitative study involving the use of a questionnaire. Ten (10) Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were conducted in the ten major mining areas on specific issues. Each group was made up of five (5) to eight (8) people, totaling seventy-five (75). Further, a total of 25 representatives of stakeholder groups were selected for the key informant interview using the purposive sampling techniques (10 chiefs, 5 respondents from NMGL and 10 respondents from the Birim North District Assembly). In all, a total of 300 respondents were sampled for the research.

Results

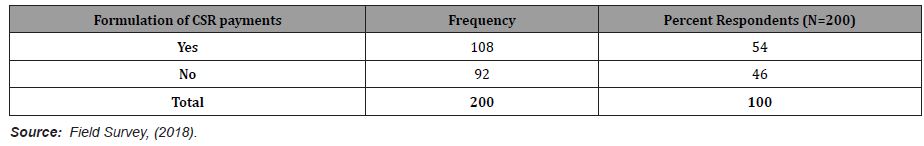

Formulation of CSR payments

Fifty-four percent (54%) of respondents indicated that, they have been directly involved in the formulation of CSR payments whereas 46% had not been involved in the payment’s formulation in their communities (Table 1).

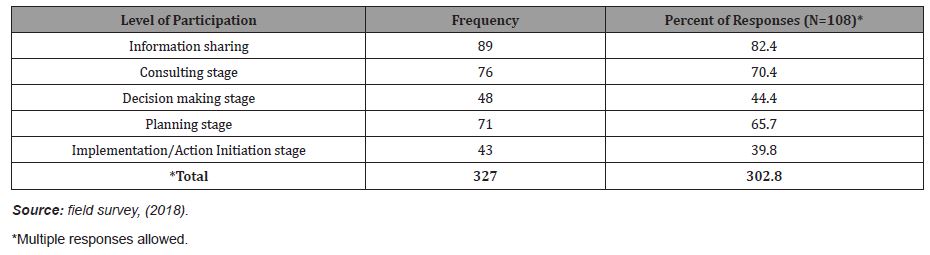

Level of Participation

With the various levels of participation of the local people in the execution of CSR payments as implemented by the mining company in the district, the majority of respondents indicated that, they were informed on CSR payments as stakeholders. More than 70% of respondents also revealed that they were consulted on such payments, whereas 39.8% take part in the implementation stage or the Action initiation stage (Table 2).

Table 1:Formulation of CSR payments.

Table 2:Level of Participation.

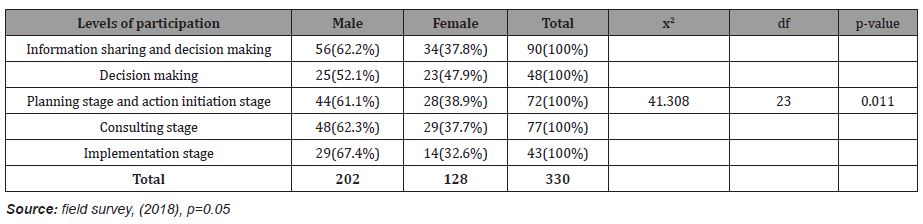

Gender and Level of participation

Table 3:Cross tabulation and Chi square tests on Gender of respondents and level of participation.

Table 3 shows 2×5 Pearson Chi square contingency test between respondents’ gender and level of participation. There is a significant relationship between these variables (x2 = 41.308; df=12; p =0.011˂ 0.05 for n = 108). This concludes that, male respondents were more engaged in different levels of participation than their female counterparts.

Community of respondent and level of participation

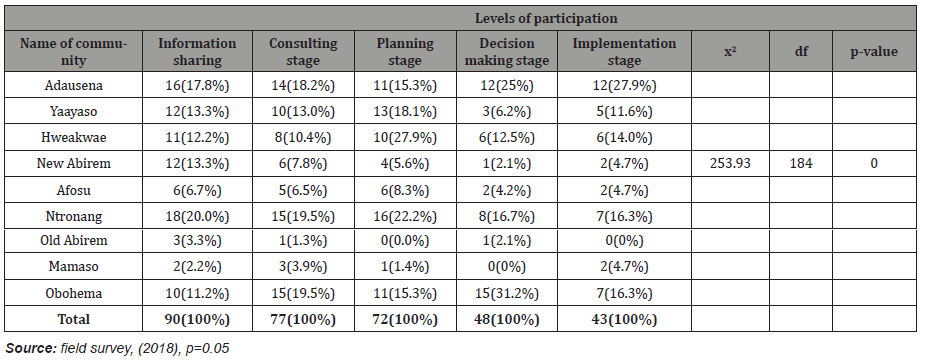

Table 4:Cross tabulation and Chi-Square Tests between community of respondent and level of participation.

The 10×5 Pearson Chi square test revealed that there is a significant relationship existing between the communities and level of participation (x2 = 253.930; df = 184; p = 0.000 ˂ 0.05 for n = 108) (Table 4). This implies that, respondents in these communities, at least, participate in one of the various levels of participation (either information sharing, Decision-making, planning, implementation, or consulting).

Institutions involved in the CSR payments of Newmont

The interview conducted with the formal institutions including, the Birim North District Assembly (BNDA), District Directorate of the Ghana Education Service (GES), Ghana Health Service (GHS) revealed that, BNDA is well integrated into the CSR payments of Akyem Newmont Ghana through the Newmont Akyem Development Foundation (NAkDEF). An opportunity is given to the Assembly to nominate two representatives (i.e., District Development Planning Officer and the District Engineer) to represent it. The CSR architecture creates space for representation of the District Assembly and other institutions in the district. These include;

i) The district works and planning officer;

ii) 1-unit committee member;

iii) 1 assembly man/woman;

iv) The district director of education;

v) The district health director; and

vi) Two representatives each from the communities.

Key informant interview with the District Director of Education revealed that Newmont involves stakeholders in CSR payments and GES plays a key role according to him, “the directorate works hand in hand with Newmont in every stage of their educational interventions from payment planning, design, decision-making, initiation and consultation stage”. (District Director of Education, 2018).

The District Director of Health Services also emphasized that, “The health directorate staff are represented in most Newmont committees and payments”. Additionally, the majority of the chiefs of the affected communities revealed that, they were involved in the formulation and execution of CSR payments at all levels of participation (planning, information sharing, consultation, decision-making and implementation/ action initiation stage).

Management of CSR Payments

CSR payments are managed by both communities and the mining company. For instance, an informant during the FGD indicated that “Upon completion, payments are managed by the mining company for a period of five (5) years before handing over to the District Assembly and the beneficiary communities”. (Participant, FGD 2018). Some participants noted that because maintenance of such payments was still done by the mining company, sustainability is enhanced. Interview with formal institutions and the Chiefs revealed that management of CSR payments was a collaborative effort and shared responsibility between the mining company, District Assembly and beneficiary communities.

Discussions

Formulation of CSR payments

The more than 50% involvement of the beneficiary communities in the formulation of CSR payments shows an indication of sense of responsibility and belongingness. Ofori and Ofori [26] emphasized the centrality of community involvement in programmes identification, design, implementation, and evaluation. According to them, the product of such participation leads to a sense of project ownership with the tendency to ensure economic development and contribute to project sustainability. Drienikova and Sakal (2012) [27] reinforces this point by noting that to identify, support and harmonise relevant interests of stakeholders, the company should have engagements with a multiplicity of significant groups. Opponents of CSR express misgivings that development projects that do little to address specific stakeholder interests and involvement of beneficiaries of CSR in project formulation will fail (Frynas) [3].

Level of Participation

Gao and Zhang [28] articulate the point that significant stakeholder engagement in the process should employ information sharing vis-a-vis proper dialogue between stakeholders and management of the organization. A summary view of the level of participation of the respondents, indicates that the majority of them participated at the information sharing level. This was followed by the consultation and planning levels, respectively. There was little participation at the decision-making stage and the action initiation stage. Arnstein [29] cited in Peprah (2001) and Tosun (2000), however, suggest that self-initiated actions are indicators of citizen empowerment and a measure of the extent of citizen power and value in participation.

Whiles the findings have shown generally that there is a significant relationship between the communities and levels of participation; it is evident from the study that the principal stakeholders as well as the beneficiary communities of CSR framework were not factored in the important levels of decision and implementation of CSR payments. This finding is in tandem with that of Maconachie and Hilson [2] when they caution that a deliberate involvement of citizens in ‘the community development programs’ financed by extractive companies does not necessarily guarantee local community participation in the decision-making process. This represents a caution that the opportunity for local actors to steer their own developmental path through making critical decisions that affect their development cannot be assumed merely on the invitation of stakeholders to participate in corporate funded activities. The implication is that without the efficient and effective involvement/participation of beneficiary communities in decision-making and implementation of CSR payments, conflicts and consistently weak local developments within host communities are envisaged [30]. The level of participation has a positive bearing on the sustainability of CSR payments.

According to Okafor [31] local communities’ participation in CSR payments yield better payments outcomes. The low level of community’s participation impacts the socio-economic development of beneficiary communities, which poses a threat to the sustenance of CSR projects. Communities’ level of participation in payments constitutes mainly being informed about what has already been decided, and the decision-making process emanates from the domain of professionals. Beneficiary communities’ levels of participation were passive and manipulative. Interaction between local communities’ was mostly limited or non-existent and people were being informed about what had already been decided and according to Tang-Lee [32] communities’ non-involvement in decision-making does not ensure equitable distribution of power and project benefits.

Further, it has been shown from the results that a significant relationship exists between gender and the level of participation. According to Keenan and Kemp [33], in assessing gender participation in CSR negotiations between companies and communities, they share the view that women have a higher tendency of involvement in a participatory, open and transparent process. They further assert that a significant approach of companies in the extractive sector to the design of their community development programme emphasizes a participatory approach with focus on gender balance. Discussions with key people within three formal institutions (namely the Birim North District Assembly(BNDA), Ghana Education Service (GES), Ghana Health Service(GHS) that play important roles in the formulation of CSR payment revealed their active involvement at all levels from information sharing to implementation stages. Responses from people within the BNDA revealed that the Assembly’s involvement in CSR was mainly through it representative on the Newmont Akyem Development Foundation (NAkDEF), namely; the District Development Planning Officer and the District Engineer.

Furthermore, views gathered from the district education directorate of the GES indicate the collaborative relationship between Newmont and the District Education Directorate in ensuring the sustainability of education related CSR. Respondents further added that the GES was fully involved in all levels. Again, since healthcare constitutes a critical focus area for Newmont, the DHMT plays a critical role in providing technical direction in CSR payments. Information obtained from the District Directorate revealed that staff of the directorate is well incorporated into Newmont’s committees that have oversight over payments. As a result of this, the district Health Directorate is fully involved in all stages of CSR payments.

Findings of the study further revealed that the chiefs who constitute the traditional representatives of the local inhabitants as well as the customary custodians of the lands were fully involved and participated at all levels of CSR payments. Formal stakeholder institution’s level of participation was seen as interactive and their participation was viewed as a right, not just as an external obligation. These findings which indicate full participation from the formal stakeholder institutions as well as traditional authorities are however at variance with findings obtained from the local population which provides a picture of limited participation, especially at the decision and implementation levels. This is in line with the findings of Van Alstine and Afiotis, (2013) in a study of the Kansanshi copper mine in Zambia. They identified a highly centralized decisionmaking process that mainly centered on discussions between the company and some institutional stakeholders, leaving little room for local participation. Cochrane [34], notes that for the long-term success of community development projects to be ensured, projects need to be self-formulated and implemented by the beneficiaries, with assistance from partners and donors. He further adds that there exist disparities between what communities perceive to be their needs and what “experts” claim they need, and this has consequences for project failure.

The interest of the beneficiary communities represented by the District Assemblies should be paramount in negotiating CSR payments. Since the District Medium Term Development Plans (DMTDPs) are a product of the aspirations and active inputs of local communities, the researcher therefore believes that the engagement of other stakeholders in the formulation of CSR frameworks on behalf of the mining company may not ensure payment support by local communities and hence sustainability might be adversely affected. The communities through their representative District Assemblies must be active participants in determining the nature of the CSR framework. This suggests that the development of CSR frameworks should be based on the DMTDPs, which serves as the major blue-print that guides developmental programs in the District. Again, in the formulation of CSR payments, the researcher believes that the District Assemblies must approve all structural designs, as there are standards. Besides, for quality assurance and safety of occupants, it is prudent for the works department of the District Assemblies to certify the consultant engaged by the mining company. The active participation of communities and District Assemblies would trigger community support and acceptance that would ensure sustained use of the payments.

Management of CSR payments

Findings gathered from the study revealed that the management of the completed CSR payments was a collaborative effort between Akyem Newmont mining company, the District Assembly and the beneficiary communities with the view to ensure the sustainable use of these facilities. Perspectives of some Chiefs and participants of FGDs indicated that, to prevent conflicts of interest, there should be enhanced shared responsibility among stakeholders in formulation and management of CSR payments. These views are in line with Harvey and Bice [35] who call for ‘collaborative moderation’-explained as working in conjunction with affected stakeholders to achieve consensus on matters deemed significant within the local context; as opposed to attempts to deal with a myriad of issues the relevance of which is determined exogenously by regulators and agencies. It was learnt that since companies have the technical capacity to ensure payment management therefore, continual company involvements in post CSR payments promote ownership and sense of interest [36, 37].

Conclusion

This study investigated Local community’s participation in formulation and management of payments of corporate social responsibility from large scale gold mining in Birem North District, Ghana. The study results revealed that more than half of the respondents were involved in the formulation of CSR payments. Again, the majority of respondents were informed on CSR payments as stakeholders. The study has further shown that communities were involved in various levels or stages in CSR payments including planning stage, decision-making stage, implementation stage and information sharing stage. However, the least amount of participation was at the implementation and decision-making stages.

Further, the results of the study showed a significant relationship between gender and level of participation, as well as community and level of participation. The study further revealed that the principal institutional stakeholders within the study communities including; Birim North District Assembly (BNDA), District Directorate of the Ghana Education Service (GES), Ghana Health Service (GHS) as well as the traditional custodians (Chiefs), were provided with necessary opportunities for involvement in the formulation and management of CSR payments. Furthermore, CSR payments are managed by both communities and the mining company, whereupon completion payments are managed by the mining company for a period of five (5) years before handing over to the District Assembly and the beneficiary communities.

Acknowledgment

Acknowledgment

Conflict of Interest

Conflict of Interest

References

- Macdonald C (2017) The role of participation in sustainable community development programmes in the extractives industries. WIDER Working Paper, pp. 28.

- Maconachie R, G Hilson (2013) Editorial Introduction: The Extractive Industries, Community Development and Livelihood Change in Developing Countries. Community Development Journal 48(3): 347-359.

- Frynas JG (2005) The false developmental promise of corporate social responsibility: evidence from multinational oil companies. International Affairs 81(3): 581-598.

- Sadik A (2013) Corporate social responsibility and the gold mining industry: The Ghana experience (Doctoral dissertation, Montclair State University). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database.

- Standing A, Hilson G (2013) Distributing mining wealth to communities in Ghana: Addressing problems of elite capture and political corruption. U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, CMI 4(5).

- Lawson ET, Bentil G (2014) Shifting sands: Changes in community perceptions of mining in Ghana. Environment, Development and Sustainability 16(1): 217-238.

- Armah FA, Obiri S, Yawson DO, Afrifa EKA, Yengoh GT, et al. (2011) Assessment of legal framework for corporate environmental behaviour and perceptions of residents in mining communities in Ghana. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 54(2): 193-209.

- Solomon M (2013) bSouth African mining in the contemporary political-Economic context. Journal of the Southern African Mining Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 113: 1-2.

- Siegel S (2013) The missing ethics of mining. Ethics& International Affairs 27(1): 3-18.

- Fraser N (2008) Scales of Justice, Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World. Polity Press, Cambridge.

- Andrews, Nathan (2015) Challenges of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in Domestic Settings: An Exploration of Mining Regulation vis-à-vis CSR in Ghana forthcoming in Resources Policy.

- Minerals Commission (2012) Guidelines for Corporate SociNal Responsibility in Mining Communities.

- Abugre JB (2014) Managerial role in organizational corporate social responsibility: Empirical lessons from Ghana. Corporate Governance 14(1): 104-119.

- EPA AKOBEN (2010) What is AKOBEN programme?

- Murombo T (2013) Regulating mining in South Africa and Zimbabwe: Communities, the environment and perpetual exploitation. Law, Environment and Development Journal 9(1): 20-31.

- Preuss L, Barkemeyer R, Glavas A (2016) Corporate social responsibility in developing country multinationals: identifying company and country-level influences. Business Ethics Quarterly 26(3): 347-378.

- Mwangi SW (2004) Community Organization and Action, With Special Reference to Kenya, Egerton University, Kenya.

- Calistus LA, Kevin OM, Evans BO (2016) Community Participation in Corporate Social Responsibility Projects: The Case of Mumias Sugar Company, Kenya. IOSR Journal of Business and Management 18(8): 70-86.

- Young IM (2011) Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton University Press, Princeton and Oxford, USA.

- Mulwa F (2004) Managing Community Based Development: Unmasking the Mystery of Participatory Development. Nairobi: Kijabe Printing Press, Kenya.

- Chitere O, Mutiso R (1991) Working with Rural Communities: A Participatory Action Research in Kenya. Nairobi University Press, Kenya.

- Chamala S (1995) Overview of participative action approaches in Australian land and water management. In ‘Participative approaches for Landcare. (Ed. K Keith), pp. 5-42.

- Kelly K, Van Vlaenderen H (1995) Evaluating participation processes in community development. Evaluation and Program Planning 18: 371-383.

- Kelly M (2001) The Divine Right of Capital: Dethroning the Corporate Aristocracy, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, CA.

- Gow D, Vansant J (1983) Beyond the rhetoric of rural development participation: How can it be done? World Development 11: 427-443.

- Ofori DF, Ofori AT (2014). Mining Sector CSR Behaviour: A Developing Country Perspective. African Journal of Management Research 22(1): 62-79.

- Drienikova K, Sakal P (2012) Respecting Stakeholders and their Engagement to decision making-the way of successful corporate social responsibility strategy. Slovak University of Technology in Bratislava.

- Gao S Zhang J (2001) “A comparative study of stakeholder engagement approaches in social auditing”, in Andriof J and McIntosh M (Eds.), Perspectives on Corporate Citizenship, Greenleaf Publishing, Sheffield, UK, pp. 239-255.

- Arnstein SR (1969) A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Planning Association 35(4): 216-224.

- Campero C, and JR Barton (2015) ‘“You Have to be with God and the Devil”: Linking Bolivia’s Extractive Industries and Local Development through Social Licences. Bulletin of Latin American Research 34(2): 167-183.

- Okafor C (2005) CDD: Concepts and Procedure. Paper delivered at the LEEMP workshop in Kainji National Park, New Bussa, pp. 2-10.

- Tang-Lee D (2016) Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Public Engagement for a Chinese State-backed Mining Project in Myanmar-Challenges and Prospects. Resources Policy 47: 28-37.

- Keenan, JC, DL Kemp (2014) Mining and local-level development: Examining the gender dimensions of agreements between companies and communities. Brisbane, Australia: Centre for Social Responsibility in Mining, The University of Queensland, Australia.

- Cochrane G (2009) Festival Elephants and the Myth of Global Poverty. Boston: Pearson.

- Harvey B, S Bice (2014) ‘Social Impact Assessment, Social Development Programmes and Social Licence to Operate: Tensions and Contradictions in Intent and Practice in the Extractive Sector’. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal 32(4): 327-335.

- Jenkins H, Obara L (2006) Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in the mining industry the risk of community dependency. ESRC Centre for Business Relationships, Accountability, Sustainability and Society (BRASS), Cardiff University, UK.

- Van Alstine J, S Afiotis (2013) Community and Company Capacity: The Challenge of Resource-led Development in Zambia’s New Copper belt. Community Development Journal 48(3): 360-376.

-

Julius Kwasi Ofori*. Local Communities’ Participation in Formulation and Management of Payments of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): A Case Study of Mining Communities in Birim North District, Ghana. On J of Arts & Soc Sci. 1(3): 2023. IOJASS.MS.ID.000511.

-

Self-mobilization, Mobilization, Beneficiary Communities, , Ghana Health Service

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.