Research Article

Research Article

Aurora’s Pearls. Niccolo Giannettasio’s Variant of the Classical Myth of Eos

Petra Aigner*

Austrian Archaeological Institute, Dep. Classics, Religious studies, Austrian Academy of Science, Austria

Petra Aigner, Austrian Archaeological Institute, Dep. Classics, Religious studies, Austrian Academy of Science, Austria

Received Date:April 14, 2025; Published Date:October 15, 2025

Abstract

The Jesuit Niccolò Giannettasio or Parthenius (1648-1715) was one of several Italian poets, who clearly saw the timelessness and versatility of the ancient myths, and playfully used to create new myths, based on the classic model. One of his works, the Halieutica, a didactic poem on fishing, composed in 1689, reveals a story about the nymph Drymo, who is hopelessly in love with the fisherman Ianthus, a son of the Ganges nymph Chrysorhoe, whom she finally conquers with the help of Aurora using a love potion made of pearls. The story tells us about fishing and the aition of the pearl. The depiction of the scene was artistically taken up by Francesco Solimena and creates a contemporaneous connection between literature and art. Although the works have been reprinted several times, there is still no critical edition. Some researchers, such as C. Schindler and Y. Haskell, have studied the author and his works in depth. Of his numerous mythographic re-creations, only a few have been edited by the author and her colleagues (see www.oeaw.ac.at/antike/mythdb). This is a representative example of how Giannettasio experimented with myths, varying genealogies or creating new ones, or setting known mythological stories in a new time and place, and the like. His works were known beyond the borders of Italy and as a Jesuit he taught for more than thirty years. Nevertheless, Giannettasio moved in some anti-Jesuit and heretical circles in Naples. However, he escaped prosecution and retired to the locus amoenus Cocomella, where he continued to write.

Keywords:Early Modern Age, Niccolò Giannettasio, Halieutica, Aurora, Drymo

Introduction

Giannettasio was a successful author in his time and his works were read beyond the borders of present-day Italy in England, France and Germany, among other places. He was highly successful in integrating his didactic poetry based on the ancient form with the Jesuit ideal of education, and was skilfully employing and creatively transforming classical myths to serve pedagogical purposes1 [1]. An example of the mythological figures of Aurora and Drymo will show here how the author poetically played with the myths and skilfully interwove them with historical and geographical circumstances to attract, entertain, and instruct the reader. He used the classical, ancient mythical figures, freely reshaped them, changed the location and the events, and combined them with new figures, so that a completely new version of the myth was created. In this way, he is in the tradition of the authors of the Renaissance, especially in Italy, who also made numerous rearrangements and new versions of myths. What is distinctive about the myth discussed here is that artistic interpretation occurred simultaneously with its literary original.

The Jesuit ratio studiorum2 of 1599 provides clear instruction on the use on pagan Latin literature in the curriculum of the Society of Jesus’ schoolmen3 [2,3]. More than 80 years later, however, at the time of our Neapolitan poet Giannettasio (1648-1715), there was still only a small step between being honoured for one’s poetry and being accused of heresy.

Nicola or Niccolò Partenio Giannettasio was born on March 5th, 1648, in Naples, where he was the only member of his immediate family to survive the plague of 1656 with any help4 [4]. So, he learnt to look after himself from an early age and taught himself mathematics, Latin, Greek and Hebrew. After studying philosophy and law, he entered the Jesuit order in 1666 at the age of eighteen 5[5]. Assigned to the teaching profession, he taught Greek, Latin, theology and philosophy at various Jesuit schools in southern Italy before being recalled to the Collegio Massimo in Naples, where he taught mathematics until 1705. He then retired and moved to Sorrento, where he continued to work until his death7 in Massa Lubrense, Sorrento, in 1715. The poet’s oeuvre included textbooks of cosmography, geography, a three-volume history of Naples(1713), and above all several collections of poems which became well known during his lifetime8 [6-8]. Unfortunately, to date there is no critical edition of his works9 [9]. To give two examples of his popularity, the Florentine librarian Antonio Magliabechi (1633- 1714) recommended the works of the Jesuit poet (‘buon poeta latino’) to the German philosopher and mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)10, who in turn recommended them to the Scottish lawyer Thomas Burnett of Kemney (1656-1729)11 [10,11].

He composed his various epic didactic poems about fishing, fishermen, seamanship, naval warfare and cosmography12 in the tradition of antiquity and the Middle Ages13. This tradition was picked up by the Jesuits in Italy and France in the 17th century, as Haskell and Schindler have described in great detail14 [12-14]. But in his poetry Giannettasio follows not only Ovid and Virgil, but none other than Giovanni Pontano (1429-1503) and the Neapolitan author Jacopo Sannazzaro (1457-1530)15 [15], both members of the Academy at Naples. In Schindler’s article she divides three types of narratives in the didactic poetry of our author, the historical, historical-biographical, and the classical myths with the invented ones16 [16]. One example of the last type just mentioned is to be introduced representatively of how Giannettasio combines ancient myths and his own inventions in a very refined and poetic way. His writing is full of geographical, historical, topographical and of course mythical references. His language is clear but verbose and long-winded. Many of his mythical narratives, such as those dealing with the figures of Columelis17 and Pausilippus18, were set in the surroundings of Sorrento, near the Jesuit villa Cocomella19, where he had already often spent time during the decades preceding his final retirement in 1705 [17-19]. This estate was situated on the seaside, founded as a convent by Jesuits in 1597. In its beautiful ambience he had apparently written his didactic poetry inspired by the idyllic environment. It seems that Cocomella served as a refuge from political and military turbulence and due to his poor health20 [20]. Giannettasio himself, in his letter of dedication to Carlo II de Cárdenas (1652-1694) in his book Halieutica, says that there was a famine in Naples (aetatis nostrae acerba nimium tabes, & penitus intoleranda). While much of Europe had been involved in the War of the Spanish Succession21 since 1701 and Prince Eugene of Savoy (1663-1736) had been expelling French and Spanish populations from Italy. Naples, until the Austrian occupation in 1707, had sometimes been close to civil war22 [21,22].

FootNotes

* For their suggestions and help I am grateful to Heinz Havas†, Gerhard Holzer and Thomas Stockinger. – All translation are made by the author, if not otherwise specified.

1 Schindler (2016: 31).

2 See chapters Regulae professoris rhetorice 10; 18 (affigantur carmina), regulae professoris humanitatis 1; 9; 10 (affigantur carmina) of the Ratio atque institutio studiorum Societas Iesu (1599). The implementation of the Jesuit theatre within the ratio studiorum in 1599 makes it clear that the regulae were loosened and not practiced down to the last dot ad comma. More than 100 000 plays were performed during 200 years, see McNaspy (2001: 3708). For the ratio studiorum see Bangert (1986²: 106); O’Malley (2006, repr. 2007: XXX-XXXI); Loach (2006, repr. 2007: 66-85).

3 Bangert (1986²: 106).

4 For further biographical information see Haskell (2003: 70-75); Haskell (2007: 188-89); Tarzia (2000: 448-449; Schindler (2001: 145; 2014: 30; 2016:24-26). A biography written by himself and intimates in the Opera Omnia Poetica I (1715: 1-9), published posthumously in the Giornale de Letterati d’Italia 38,1 (1727), 269-289. Mazzarella (1816: 5 pp.).

5 Haskell (2003: 71-72).

6 Collegio di Amantea in Calabria (Latin and Greek), Collegio di Palermo and Naples (theology, philosophy), Reggio di Calabria (philosophy), Naples (mathematics). See Tarzia (2000: 448-449), also Haskell (2007: 188).

7 Schindler (2002: 245-260).

8 Piscatoria (thirteen eclogues) et nautica (eight books) (1685, 1686, 1692), Universalis Cosmographiae elementa (Naples 1688, 1701), Halieutica (Naples 1689, 1715), Universalis geographiae elementa (Naples 1692), Naumachica seu de bello navali libri V (1694, 1715), Aetates Surrentinae (1696), Bellica (fifteen books, 1697, 1699), Autumni Surrentini (1698), Ver Herculanum (1704), Opera omnia poetica (Naples 1715), Historia Neapolitana (Naples 1713), Hyemes Puteolanae (posthumously edited in the Annus eruditus 1722), Xaverius Viator seu Saberidos (unfinished, posthum Naples 1721), and various poems. On the popularity of Giannettasio’s poetry, see Grant (1965: 216) and (2022: 399-400).

9 See the translation of the 8th book of the Nautica by Navarro Antolín (2023).

10 Letters of Antonio Magliabechi an Leibniz: in May 1699, Nr. 105, see Gädeke-Van den Heinzel (2001: 135), in November 1694, Nr. 437, see Utermöhlen- Scheel-Müller (1979: 631), in July 1692 Nr. 195, see Scheel-Müller-Gerber (1970: 329).

11 A letter in July 1696, Nr. 469 Leibniz an Thomas Burnett of Kemney, “Il faut les exhorter à entreprendre quelque belle matiere, à l’example des peres Rapin et Giannettasius. Je me plaisois autresfois à la poësie.”, see Bungies-Heinekamp (1990: 731).

12 See note 8.

13 See Haye (1997: 39-44; 132-167; 303; 348), Roellenbleck (1975: 7-26), see in general with the introduction of Haskell – Hardie (1996). See Malatesta Fiordiano’s catalogue of fishes (Operetta non meno utile che dilettevole, della natura, et qualità di tutti i pesci … Rimini: Pasini 1576).

14 Schindler (2014: 36-39; 2016: 24-40) with the latest bibliography. Haskell in her comprehensive and excellent monography Loyola’s Bees (2007) and her chapter about Giannettasio pp. 70-82; Haskell – Hardie (1999).

15 Nash (1966: 7-26, especially 8-9), his academy-name was Actius Syncerus.

16 Schindler (2002: 246-247); Schindler (2003: 298).

The Didactic Latin Poem Halieutica (Naples 1689)

Giannettasio’s Halieutica in ten books, a didactic epic poem about fish and fishing, was first printed in 1689 and reissued in 1715 as part of his Opera Omnia Poetica. The subject was one that had been dealt with since ancient times23 [23]. The Halieutica of Oppian (c. 200 AD) and Nemesianus (c. 250 AD)24 (whose poem of the same name is sometimes attributed to Ovid) had been handed down from late Antiquity. In the Middle Ages Oppian was frequently used, as can be seen from the large number of surviving manuscripts25, and was commented on, e.g. by Tzetzes (c. 1100 - c.1180/85)26 [24-26]. Various editions followed at the beginning of the 16th century27 [27]. But as Giannettasio himself noted in the introduction to his Nautica, his role model was the Neapolitan poet Jacopo Sannazzaro (1458-1530). He had been the first to introduce fishermen instead of or beside the traditional shepherds of pastoral poetry28, and the setting of his five Eclogae piscatoriae had not been Arcadia, Sicily or the like, but the surroundings of Naples29 [28,29]. Sannazzaro himself had been inspired by the poetry of Vergil (70-18 BC) and Theocritus’ (c. 300 – c. 260 BC) Idyll 21 (Ἁλιεῖς)30 [30]. That Giannettasio was taken with the theme of fishing becomes evident not only in the 13 eclogues of his book Piscatoria (1685), but also in the Autumnus Surrentinus ‘Autumn in Sorrento’ as part of his Annus eruditus. There he also discussed his approach to combining pastoral and didactic poetry, stating that his work was fictitious in terms of events and characters, but that he took no liberties with the description of art or history [31]31.

His tenth book of the Halieutica begins with a description of the origin of pearls32 and of the different types of pearl-oysters found in the Indian and Arabian world. Here our poet follows the ninth book of Pliny’s (23 – 79 AD) Naturalis Historia, but expands on some of the details. He tells us where and how the pearls are collected: mostly, oysters are taken by net, sometimes by divers known as urinatores33 (Hal. p. 234), who use pegs or clips for their noses and olive-oil for their ears. They hang by a rope from the boat, or cymba, and have a heavy stone bound to their lower legs. Some have to fight against a kind of seal34: turmatim vituli cursant, turpesque nefando | ore canes …. Hos tuberones Indi cognomina dicunt. (“Calves in hordes swim around them, terrible dogs with a horrid maw … These the Indians call the hunchbacked ones”, Hal. p. 235). The Indian fishermen overcome these beasts by singing: has Indi suevere … rapaces | thessalico de more feras vincire canendo (“the Indians usually … bound these wild beasts in a Thessalian mode by singing”, Hal. p. 235). The fishermen first have to lay hands on the reges concharum (“the king-oysters”), at which point totum gemmiferae gentis captabitur agmen (“the whole flock of the pearlbearing oysters will be taken”, Hal. p. 237). In this, too, Giannettasio follows Pliny’s description of concharum … duces35 [32-35].

Foot Notes

17 Giannettasio, Naut. 9, p. 210f.; Hal. 3, p.77.

18 Giannettasio, Hal. 9, p. 212f.; Bell. 2, p. 108f.

19 In 1711 Schinosi claimed that the villa and its surroundings had been called Cocomella since ancient times, see Schinosi (1711: 336-341, esp. 340): “…chiamato ab antico La Cocomella…”; Iapelli (2003: 247-257); Haskell (2003: 73-74). Today it serves as a hotel. There, Giannettasio wrote like his idol Sannazzaro, who, apart from his three-year exile in France, wrote in his Villa Mergellina on the Gulf of Naples.

20 See the paper by Haskell (2007: 187-213), especially p. 194-195.

21 1701-1714, where at the end Giannettasio’s hometown Naples fell to the Austrian Emperor Charles VI together with Milan, Toscana and Sardinia.

For the decline of Naples in the 17th century and development of an impressive new intellectual life see Stone (1997: 1-23).

22 Like the Macchia conspiracy against the Spanish viceroy in Naples in 1701, which was put down; the Prince of Macchia fled to Vienna, where he died. For the political situation, see Musi (2013: 144-145). Giambattista Vico (1668-1744) wrote a panegyrical historiographical work (in support of Charles VI) on these events, the Principum neapolitanorum conuirationis anni MDCCI historiae, in 1703; Stone (1997: 148).

23 See for further literature and information Haye (1997: 303, 348); Colonna (1963: 101-104). Giannettasio, as Haskell (2003: 81, note 26), suspects, ‘may have consulted’ the Jesuit Johannes Eusebius Nieremberg’s (1595-1658) Historia naturae, Antwerp 1635, for the zoological information.

24 For an introductory bibliography see Bartley (2003: 1-4), Fajen (1999: VI-XIII). Giannettasio follows Oppian in the description of his ideal fishermen concerning their physical and mental qualities, see Haskell (2003: 79, note 22) and Giannettasio, Hal. 3, p. 29-49. For Oppian’s probable Greek sources (Leonidas of Byzantium, Demostratos, Alexander of Myndos), see Fajen (1999: XI, n.21); Wellmann (1895: 171, 173); Keydell (1937: 430-434).

25 Oppian’s Halieutica in five books on salt water fishing survived in 58 manuscripts, Bartley (2003: 2).

26 See the edition of Dübner, Fr. – Bussemaker, U. Cats. 1849. Scholia in Theocritum… scholia et paraphrases in Nicandrum et Oppianum, Paris: Diderot, and for other scholia see Leverenz (1995:101-103).

27 Editio princeps Venetiis 1517, for further editions see Fajen (1999: VI, n. 2).

28 Giannettasio, Nautica, Ad lectorem: Qui primus … piscatores introduxit in eclogis, see Schindler (2003: 298 with n. 26).

29 Grant (1957: 71-72); Grant (1965: 205), see also Putnam (2009: XIV), and for further bibliography Nash (1996: 67).

30 Nash (1966: 18-20, 23).

31 Giannettasio, Autumnus Surrentinus, Lib.2, cap.2: … at cum artem quampiam versu tradimus, aut historiam referimus, nulla nobis scribendi libertas conceditur. “… but when we hand down any art in verse, or report history, we are allowed no liberty in writing.”

32 See Pliny, NH 9, 107-109.

33 See Pliny NH 9, 111 (55/35).

34 See Pliny, NH 9, 110 (55/35). In alto quoque comitantibus marinis canibus “those, which lie out in the main sea are generally accompanied by sea dogs” transl. Bostock-Riley.

At this point, our author raises the question of who first brought the originally divine pearls to mankind: Nunc age, qui primus Titanidis aurea nobis | Aurorae ostendit divino numine dona

(“Now tell us, who was first to show us the golden gifts of the Titanide Aurora by a divine sending”, Hal. p. 239). The myth of Aurora’s pearls is then related on six pages.

But first, an overview of the facets of figure of Aurora in antiquity, to see how Giannettasio varied this myth.

Aurora in Antiquity

The myth of Eos or Aurora itself has a comparatively homogeneous tradition since Homer and Hesiod, with some variations in the genealogy and in the selection of her various amorous stories. More often she is the personification of dawn or stands for the East itself. Giannettasio’s role model Sannazzaro had likewise used Aurora primarily in a metaphorical way36 [36]. The Greek goddess Eos (Ἠώς) of dawn37, with the epitheton the ἠριγένεια38, ‘born in the early morning’ (ἦρι), the Latin Aurora39, is well-known in various stories in antiquity. Hesiod tells us she is the daughter of Theia and Hyperion40, sister of Selene and Helius, mother of the strong-hearted winds Zephyrus, Boreas, Eurus and Notus, whom she bears to Astraeus (the starry), further Eosphorus (the dawn-bringer, the morningstar41) and the stars42 [37-42]. Ps. Apollodorus (1st - 2nd c. AD) writes that she repeatedly falls in love with mortal men because Aphrodite has cursed her for having a liaison with Ares43. Among these mortals are the handsome hunter Orion, who dies through Artemis’ arrows, because the gods envy Aurora44 or Cephalus, whom she steals away from his beloved Procris45 and by whom she becomes, again according to Hesiod, the mother of Phaethon46 [43-46]. But mainly, Eos, the ‘rosy-fingered’ (ῥοδοδάκτυλος47) goddess, is connected with Tithonus, a son of Laomedon and brother of Priam48, whom she abducts to Ethiopia or to the Oceanus49 and to whom she bear Memnon and Emathion50 [49-50]. She is represented as rising from Tithonus’s bedside to bring the light of morning to mankind and gods51 [51]. Their sons appear as allies of the Trojans, Memnon is dying in a duel with Achilles52 [52]. Eos carries off his body to mourn for him53, as is told in detail by Quintus Smyrnaeus (3rd c. AD) in his second book54, and as she is crying her tears fell to the earth like dew55. This dew (gr. ἡ ἔρση, ἡ δρόσος, lat. rōs, rōris m.56) is her gift to mankind. Further epithets for Eos include ‘fair-haired’ (εὐπλόκαμος), ‘goldenthroned’ (χρυσόθρονος), ‘gold-sandaled’ (χρυσοπέδιλλος59); Homer describes her as riding in a golden chariot drawn by winged horses60. Likewise Homer, ibid., narrates her most famous role beside her love affairs, where Athena holds back Eos on the Oceanus without letting her harness the horses Phaëton and Lampus, while Odysseus and Penelope are enjoying their reunion [53-59].

Foot Notes

35 Pliny, NH 9, 111 (55/35).

36 Some examples: Sannazzaro epig. 2,48,8; de partu Virginis 1,18; 1,369; 1,434; 3,6; ecl. 5, 65. Apart from an exception in a love poem, like epigr.

16,25 iam non maluerim mihi beatas Aurorae Venerisque habere noctes (“I would not now prefer to have the blissful nights of Aurora and Venus…”)

37 For Eos as day or daylight is documented by Eur. Troad. 847, Paus. 1,3,1. And some Scholia to Pindar’s Ol. 2, 148; Nem. 6,85 and Scholia to Homer

Il. 3, 151, whereas Homer knows her only as dawn.

38 Hom. Od. 22,197; Apoll. Rhod. 2,450.

39 Eos, Hunger-Harrauer (1998: 158ff.); Ov. met. 9,420 is the only to call her Pallantias (daughter of Pallas, a Titan and brother of Hyperion), see Ov.

fast., 4,373, 15,700; 6,567) but different Ov. fast. 159 Hyperionis (daughter of Hyperion), see, Haupt-Korn, 2, ad 421, p. 98. Eos, Roscher I,1, 1252-

1278. Eos, Jacob Escher-Bürkli, RE V,2, (1905, repr. München 1987), 2657-2669; Hes. Theog. 371-373: “And Theia was subject in love with Hyperion

and gave birth to great Helius (Sun) and clear Selene (Moon) and Eos (Dawn), he who shines upon all is on earth and upon the immortal Gods who

live in the wide heaven”. Θεία δ’ Ἠελιόν τε μέγαν λαμπράν τε Σελήνην | Ἠῶ θ’, ἣ πάντεσσιν ἐπιχθονίοισι φαείνει | ἀθανάτοις τε θεοῖσι, τοὶ οὐρανὸν

εὐρὺν ἔχουσι, | γείναθ’ ὑποδμηθεῖσ’ Υπερίονος ἐν φιλότητι. Theog. 378-80: “Eos bore to Astraios the strong hearted winds, brightening Zephyrus and

Boreas, headlong in his course and Notus, a goddess mating in love with a god. And after these Erigenia [Eos] bore the star Eosphorus (Dawn-bringer),

and the gleaming Astra (Stars) with which heaven is crowned.”. Ἀστραίῳ δ’ Ἠώς ἀνέμους τέκε καρτεροθύμους, | ἀργέστην Ζέφυρον Βορέην

τ’αἰψηροκέλευθον | καὶ Νότον, ἐν φιλότητι θεὰ θεῷ εὐνηθεῖσα. Daughter of Helios Pind. Ol. 2,35, daughter of the Night Aeschyl. Ag. 265.

40 Hyperion and Euryphaessa see Hom. Hymn. 31,6. Daughter of Helios see Pind. Ol.2, 58; Dionys. Hymn. 2,7, Orph. hymn. 8,4. Daughter of Euphrone

(Nyx) see Aeschyl. Ag. 265, Nyx see Quint. Smynrn. 2,625, Tzetzes Hom. 285.

41 Eosphoros as dawnbringer precedes Eos, see Ov. Her. 17,112; Met. 11,296.

42 Further children Dike/Iustitia Arat, phainomena 98; Schol. Hyg. Astr. 2,25.

43 Apollod. Bibl. 1,27 Aphrodite made her constantly fall in love (συνεχῶς ἐρᾶν, ὅτι Ἄρες συνευνάσθει), because Eos had an affair with her husband

Ares. These men were Orion, Tithonos, Kephalos and Kleitos.

44 Hom. Od., 5,121ff. or Apollod. Bibl. 1,4,5. with other causes of death.

45 Eur. Hipp. 454 f., Apollod. Bibl. 1,9,4; Ov. Met. 7,700ff; Paus. 1,3,1. (“On the tiling of this portico [the Royal Portico at Athens] are images of . . .

Hemera (Day) [i.e. Eos the dawn] carrying away Kephalos, who was in love with him. His son was Phaethon, afterwards ravished by Aphrodite . . .

and made a guardian (daimon) of her temple. Such is the tale told by Hesiod, among others, in his poem on women.” (transl. Jones.); Hyg. Fab. 189.

46 Hes. Theog. 986 ff. “Then [Eos], embraced by [a mortal] Kephalos, she engendered a son, glorious Phaethon, the strong, a man in the likeness of

the immortals; and, while he still had the soft flower of the splendour of youth upon him, still thought the light thoughts of a child, Aphrodite, the lover

of laughter, swooped down and caught him away and set him in her holy temple to be her nocturnal temple-keeper, a divine spirit (Daimon Dios) [i.e.

a star]” (transl. Evelyn-White). See Paus. 1,3,1.

47 Different explanations, on the one hand rosy colored rays similar to the hand’s fingers (Welcker, Griechische Götterlehre, 1, 683) or (Preller 1,343;

Jordan, Jahrbuch für Philologie 1873, 80) as seizing roses etc. her garment often named κροκόπεπλος yellow or saffron-colored, see Homer Il. 19,1

Ἠὼς μὲν κροκόπεπλος ἀπ᾽ Ὠκεανοῖο ῥοάων | ὄρνυθ᾽, ἵν᾽ ἀθανάτοισι φόως φέροι ἠδὲ βροτοῖσιν, her wings are white λευκόπτερος; Il. 8,1; see Eur.

Troad. 847.

The picture drawn by the author is that of a sublime goddess

living in her luxurious palace but helping a young nymph to fulfill

her desires. The content of the narrative closely resembles a fairytale.

A young maiden in love has to win her beloved’s heart with a

love potion. But Giannettasio embeds the whole story in his didactic

poem, using it to explain the genesis of pearls, and he moves the

setting to the river Ganges, introducing three new characters to

interact with Aurora. The first one is Chrysirhoe (gr. χρυσορόης “streaming of

gold”), a nymph of the Indian river Ganges. She is the mother of the

fisherman Ianthus; both have no ancient equivalent. Giannettasio

provides her with no further characterization. The third protagonist

is the nymph Drymo61, Δρυμώ. This name is attested as that of a

Nereid in Vergil’s Georgica62, and Hyginus (64 BC – 17 AD) lists her

in the preface of his Fabulae63, without giving any characteristic or

story behind her. Sannazzaro also mentions her only by name64.

Giannettasio introduces her simply as “a very beautiful nymph”

(Hal. p. 240) [59-63]. The setting is in India, by the river Ganges, near and in a

cave (spelunca), where Ianthus, a handsome fisherman of the

Agarid lineage lives: Extremo quondam, ut perhibent, piscator

Eoo | Agaridum de gente fuit, cui nomen Iantho (“Long ago in the

extreme East, as they say, there was a fisherman, whose name was

Ianthus, from the Agarid line”, Hal. p. 239). This genealogy has been

mentioned already some lines before: vati vos, ò Chryseides, & et vos,

| Agarides, monstrate viam per caerula Divae (“O you Chryseids and

you Agarids, show this singer the way through heaven to the deity

[Aurora]”, Hal. p. 239). Giannettasio had previously introduced

these nymphs in the opening verses of book eight of his earlier

didactic poem, the Nautica (1685): & umbroso Bepytri a vertice

nymphae | Agarides rutilaeque vocant Chryseides auro, | omnes

Aurora genitae, & Titanides omnes (“and from the shady peak of

Bebytrus the Agarid nymphs and the golden-shining Chryseids call,

they are all Aurora’s offsprings and all Titanids”65). Thus, if Aurora

cares for the fisherman Ianthus, it is because he is a descendent of

her own line. The Agarids, as is explained in a footnote, derive their

name ab Agarico sinu, qui Gangetici pars est (“from the Agaric Bay,

which is part of the river Ganges”66). This geographical information

may derive from the seventh book of Ptolemy’s geography. While

in general, the geography67 of India had been well known through

Portuguese exploration and conquest from 1505 onward, the

Ganges River mouth in Bengal was not as thoroughly investigatedas one might have expected by the early 18th century68. 48 Diod. 4,75,4.

49 When a goddess abducts a mortal, this could be understood as the death of the concerned person, see L. Radermacher, Das Jenseits im Mythos

der Hellenen, Bonn 1903, 113ff. See Ganymed through Zeus or Endymion, Hunger-Harrauer, 158f.

50 Hes. Theog. 984ff., Apoll. Bibl. 3,147.

51 Hom. Il.11,1f. ἠὼς δ᾽ ἐκ λεχέων παρ᾽ ἀγαυοῦ Τιθωνοῖο ὄρνυθ᾽, ἵν᾽ ἀθανάτοισι φόως φέροι ἠδὲ βροτοῖσι. “Now Dawn rose from her couch from

beside lordly Tithonus, to bring light to immortals and to mortal men”, transl. Murray. Hom. Od. 5,1f. She forgot to wish the lover immortality, so that in

the end he was transformed into a cicada, Schol. Hom. Il. 3,151,11,1; Hom. Hymn. Aphrod. 218ff., where he babbles endlessly. Mimnermos fragm.4

(“He [Zeus] gave Tithonos an everlasting evil, old age, which is more terrible than even woeful death.”).

52 Hom. Od. 4,188, Hes. Theog. 984f., Pind. Ol. 2,83, Apollod. Bibl. 3,12,4; Arctinus Milet, Aethiopis fragm. 1, Quintus Smyrnaeus 2.549, Pind. Nem.

6, 49-53; Diod. 4.75.4, Callistratus Descriptions 9; Ov. Fast. 4.713.

53 Ov. Met. 13,581f., Sen. Troad. 239f., Callistratus, descr. 1; 9; Philostratus Elder, 1,7.

54 Quintus Smyrnaeus 2.594-666.

55 Ov. Met. 13,621f. (Luctibus est Aurora suis intenta, piasque | nunc quoque dat lacrimas et toto rorat in orbe “Aurora intent on her own grief: now still

her loving sorrow she renews and with her tears the whole wide world bedews”, transl. Melville; Verg. Aen, 8, 384; Serv. Aen. 1,489.; Serv. Georg.3,

328).

56 roscidus dewing, let dew falling; oldindic rasā wet.

57 Hom. Od. 5, 390.

58 Hom. Od. 15,250.

59 Sapp. fr. LP 103, 13; LP 123, 1.

60 Hom. Od. 23,243-46 Ἠῶ δ᾽ αὖτε | ῥύσατ᾽ ἐπ᾽ Ὠκεανῷ χρυσόθρονον, οὐδ᾽ ἔα ἵππους | ζεύγνυσθ᾽ ὠκύποδας, φάος ἀνθρώποισι φέροντας, | Λάμπον

καὶ Φαέθονθ᾽, οἵ τ᾽ Ἠῶ πῶλοι ἄγουσι. The chariot of Helios is missing in Homer.

61 For Drymo see W. H. Roscher, Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie, 1,1, 1203. RE V,2, 1745, Jacob Escher-Bürkli (repr. Munich

1987).

62 Verg. Georg. 4,336 ff. At mater sonitum thalamo sub fluminis alti | Sensit. Eam circum Milesia vellera Nymphae | Carpebant hyali saturo fucata

colore, | Drymoque Xanthoque Ligeaque Phyllodoceque, | caesariem effusae nitidam per candida colla,… „But his mother heard the cry from her

bower beneath the river’s depths. About her the Nymphs were spinning fleeces of Miletus, dyed with rich glassy hue – Drymo and Xantho, Ligea and

Phyllodoce, their shining tresses floating over snowy necks.” (transl. Fairclough).

63 Hyg. Fab.praef. VIII. Ex Nereo et Doride Nereides quinquaginta, Glauce Thalia […] Drymo …].

64 Sannazzaro, ecl. 4, Proteus, 56 candida Drymo (“snow-white Drymo”) receiving Nesis.

65 Giannettasio, Naut. p. 221.

Drymo, as Giannettasio tells us, is flushed with love for Ianthus

(Illum … ardebat, Hal. p. 240). But Ianthus is not impressed and

withstands (aversatus) all her entreaties (mollia verba et preces

multae, sacrae taedae coniugii, “tender words and frequent asking,

and the sacred conjugal torches”), because he wants to preserve

his purity (fixum est animo servare pudorem). So Drymo travels by

divine chariot (caeruleis bigis) to the Far East (Hal. p. 240). The bigae

in Antiquity are reserved for gods like Luna, Aurora, Venus, and for

chariot races69. There she comes to Aurora, whom she addresses

as “Mother Dawn” (mater Eos), in her palace (Hal. p. 240)70, which

is described in great detail. The house rests on a hundred white

pillars, reaching to the highest (poloque aequata supremo); it has

a shining silver roof with a thousand sparkling stars. The walls

are of diamond and jasper with crimson shining points. The floor

gleams with flowers, the wide doors with gold. There is a bright

temple with twelve columns, where a thousand everlasting flames

nurtured with Arabian balsam-oil and incense are burning. So Drymo asks for help and recounts her sorrows to Aurora:

Tu, Dea, praeduram pueri da flectere mentem, | qui dulces spernit

thalamos, & foedera sancti | coniugii, fastuque preces, & dona superbo

| contemnit Nymphae, magno quae sanguine Divùm | creta est, &

Divos inter, Nymphasque sorores | Agaricis71 late dives dominatur in

undis (“You, Goddess, let the stubborn mind of this boy be changed,

who spurns the sweet nuptials and the holy bonds of matrimony,

who disdains with haughty pride the pleas and gifts of the Nymph,

she who is sprung from the famous blood of the Gods, and who rules

in plenty far and wide among the divines and her sister nymphs in

the Agaric waves”, Hal. p. 240f.). Drymo wants a legitime marriage

(legitimum peto coniugium). Aurora answers her “don’t doubt, Drymo, my blood” (ne dubita,

Drymo, sanguis meus). The goddess accepts her as a blood relative

and, well known for her experience in love affairs, advices her to

mix a potion made of pearls dissolved in vinegar: accipe, & aurati

transfer te Gangis ad ora. | Hic tibi nativam divini roris in undam

| Acre coruscantes gemmas dissolvat acetum. | Amplaque gemmato

replebis pocula succo | … Adveniet, diique bibet nova pocula roris,

| Duritiem ex animo ponet, fastumque superbum (“Take them [the

pearls] and proceed to the mouth of the golden Ganges. Here in

the native water of the divine dew may strong vinegar dissolve the

shining pearls. | You will fill capacious mugs with the pearl-juice …

He will come and drink from the new mug with the divine dew, |

and will put off the hardness from his mind, and the haughty pride”,

Hal. p. 241). Pliny tells us a similar, famous story in his ninth book: that

of Cleopatra’s extremely precious pearl, which she dissolved in a

strong solution of vinegar to win a bet against Antonius as to who

could spend more money on a single banquet72. Here the nymph

Drymo is instructed to serve him the solution in a cup decorated

with pearls and then hide herself. Her beloved Ianthus comes home

very tired from fishing and thirsty. He drinks the love-potion and

wonders about the pearls, and when Drymo appears, he falls in love

with her. She teaches him pearl-fishing and tells him the story of

origin of the pearls: namely, that Aurora is crying over her dead son

Memnon and Sol turns her tears into pearls. What, then, are the differences and the parallels between this

and the familiar ancient myth? Aurora is introduced as Tithanis,

daughter of a Titan; in Antiquity, her father was the Titan Hyperion

or occasionally Pallas. The poet, who refers to himself as vates,

wants to be guided through the air to the divine goddess73. Four

of her sons are mentioned: aside from Memnon, the winds Notus,

Eurus and Favonius, a mild west wind corresponding to Zephyrus.

Also familiar from ancient myth are the chariot and the dense cloud,

but the description of the palace in great detail is new. Moreover,

the version of how Aurora learns of the death of her son Memnon

and how she copes with it is considerably embellished. Her son, a

dark-faced man (ora niger) but handsome (sed pulcher erat, Hal. p.

243), as a nephew of Priam fights on the Trojan side and falls by

Achilles’s weapons after having slain Nestor’s son Antilochus74. Up

to this point, Giannettasio has more or less followed the ancient

model, but then he continues: 66 Giannettasio, Naut. 221; In the same marginalia of the augmented reprint of 1715 in Naples, p. 222: Chryseides see note 3 A sinu Magno, qui &

Chryse dicitur “from the Great bay (nowadays bay of Martaban), which is called too Chryse”. This last mentioned Chryse might be Aurea Chersonesus

(Plin. HN 6,21; Pomp. Mela 3,7; Ptol. Geogr. 7,2,5). See Virgil, Georgica 3,27 where he refers to the Gangarides. Besides the Agarides are mentioned

as the Arabian off-springs of Sarah’s Egyptian handmaid Hagar/Agar and Abraham, see Gen. 16 and 21.

67 India intra et extra Gangem, see Berggren – Jones (2001: 109, 140-141; 173). For the knowledge of India in antiquity and in the didactic epic Cynegetica

(of a Syrian author of the beginning of the 3rd century AD) see Bartley (2003: 4; 287).

68 Prasad (1980), 153-154, 254. Lach - Van Kley (1998: 142-143; 259).

69 Hurschmann, Rolf. 2015. “Bigae.” Brill’s New Pauly. Antiquity volumes edited by: Hubert Cancik and Helmuth Schneider. Brill Online, 2015. Reference.

Universitaet Wien. 20 March 2015 http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/brill-s-new-pauly/bigae-e217040, first appeared online: 2006;

Pollack, E. 1897 (1991). “Bigae”. Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Neue Bearb. Hrsg. Von Georg Wissowa, 5, 465-

467, München Druckenmüller (repr. München-Zürich: Artemis & Winkler).

70 Compare with Lucan’s depiction of Cleopatra’s palace Lucan. 10,111-135.

71 Ἄγαρα, see Ptol. Geogr. 7, 1, 67, the city in India within the river Ganges on the Agaricus bay.

72 Pliny, NH 9, 120 (58/35).

73 Guided by Chryseides and Agarides, Hal. p.239.

74 The tradition goes from Hom. Od. 4, 190ff. to late antiquity.

Et jam Tithoni linquens Aurora cubile,

Non pexis de more comis, nec concolor ostro,

Sed ferrugineis surgebat lutea bigis,

Venturi ceu gnara mali, cum Vespere ab atro

Flebilis ldææ referens insigne cupressi,

Conspectus lentis properare Favonius alis.

Ilicet inspecta ferali Aurora cupresso,

Palluit, & reliquum defluxit ab ore decoris.

(“And already Aurora, leaving the marital bed of Tithonus,

neither decently combed as usual, nor the same purple color, but

rather yellow-golden, rose in her dark-colored chariot, as if aware

of the coming evil; when from the dark western sky she saw

Favonius flying hurriedly on his gentle wings, bearing the sign of

the mourning Trojan cypress. When Aurora caught sight of the

funereal cypress, she turned pale, and the remnants of composure

fled from her face”, Hal. p. 243). Apparently, after Memnon’s death Aurora has a premonition

of what has happened. She leaves Tithonus’s bed and rises with

her chariot in a dishevelled state rather than in her usual glory.

The subsequent scene in which she encounters her son Favonius

bearing a cypress branch is completely new. It replaces the more

usual burial scene, which may be exemplified by Ovid’s account in

the thirteenth book of his Metamorphoses75. Here Memnon’s body

is burnt on a funeral pyre, birds (the memnonides) are formed out

of the rising ashes, and their fighting against each other and their

dying again is repeated every year. Aurora typically watches this

scene and turns pale, which has an impact on the cycle of day and

night, and sheds her tears, the dew, onto the earth76. In Giannettasio’s scene, Favonius informs Aurora of her son’s

fate, and she breaks down. When Sol sees her drenched in tears, he

learns what has happened. He tries to comfort her because many

of her tears are falling down as dew. So, Sol turns them into white

pearls: Et nostras olim lacrymas, nunc munera Solis (“And my former

tears are now Sol’s gifts”, Hal. p. 241). Rorantes reduci perfundens

lumine guttas, | Protinus in niveas jussit concrescere gemmas (“By

filling the dew drops with his returning light, immediately he caused

them to harden into snow-white gems”, Hal. p. 244). Thereupon,

the oysters in the sea greedily devour the falling dew-pearls, then

wonder because the unusual pearls are shining brightly in their

bellies: … Rores | Deciduos avido ceperunt gutture Conchae. | Miratae

insolitas utero candescere baccas (“The mussels seized the falling

dew in eager maws, wondering that in their belly unusual pearls

were shining bright”, Hal. p. 244). This is the story told by Drymo,

who adds that if the oysters consume the dew in the morning, they

produce white pearls, and if in the evening, red and dark-flecked

ones will result77. The story of the falling dew generating pearls is generally

known from Pliny’s ninth book: pandentes se quadam oscitatione

impleri roscido conceptu tradunt, gravidas postea eniti, partumque

concharum esse margeritas pro qualitate roris accepti78 (“It is said

that, yawning, as it were, it opens its shell, and so receives a kind

of dew, by means of which it becomes impregnated; and that at

length it gives birth, after many struggles, to the burden of its shell,

in the shape of pearls, which vary according to the quality of dew”.

Transl. by Bostock-Riley v. 2, 1855: 431) [1]. According to Pliny, the

more beautiful the pearl is, the better the quality of the dew, and the

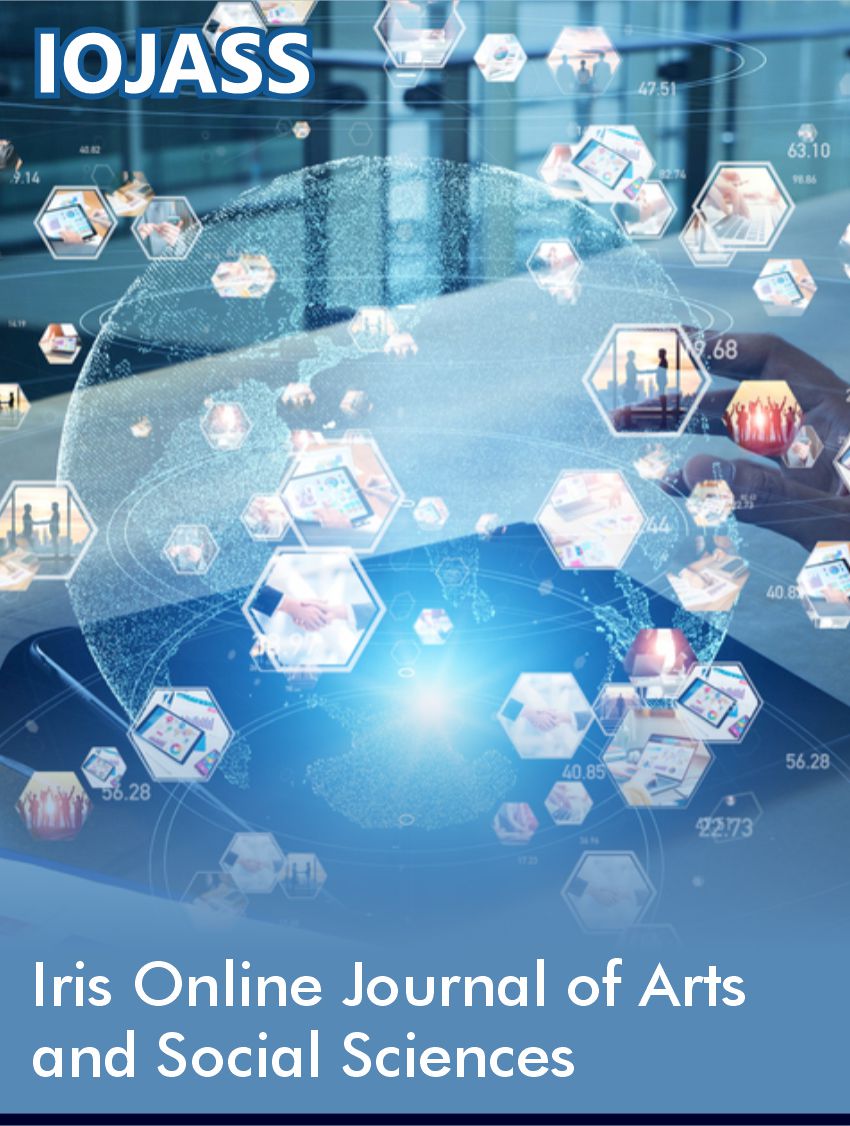

calmer the sea will be. To embellish his story and maybe also to help the reader to

better understand, Giannettasio requested a friend of his to enrich

his book of 1689 with eleven illustrations. This was Francesco

Solimena (1657-1747), together with the engravers Hubert Vincent

(fl. 1680-1730) und François de Louvemont (c.1648- c. 1695)79.

The image (p. 222, Naples 1669) that goes with this myth is that of

Aurora holding the torch in her right hand. On the left is Zephyrus,

her son, with the funereal cypress, and in the water is a male figure,

presumably a sea-God, half standing in the sea, collecting Aurora’s

tears in form of dew-pearls with an oyster. In the foreground there

are two females with half-open oysters. (Figure 1) 75 Ov. Met. 13, 600-623. View the black figured Vase of the beginning 6th century, where Eos holds her dead son Memnon in her hands and above

them a black bird, interpreted as Memnon’s soul http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/56.171.25 [2014-05-25].

76 Paus. 5,19,1; Ov. Met 13, 580-622. 77 See Pliny HN, 9, 107 (35/54) he too tells the story, when dew falls in the opened oysters, they give birth to pearls. The clearer the dew, the whiter

the pearl. 78 Pliny, NH 9, 107 (35/54). 79 François de Louvemont (1648 - c.1695) was born at Nevers. Very little is known about him, view Thieme-Becker 23 (1992: 419); Santoro-Segatori

(2013: 203); Hubert Vincent, born in Lyon, was a French engraver who spent years at Rome in the beginning of the 1680ies till 1727, view Füssli

(1816: 3080), Thieme-Becker 34 (1992: 381). Francesco Solimena (1657-1747), known as l’abbate Ciccio80,

nine years younger than Giannettasio, was born in Canale di Serino

in Campania, but settled and prospered in Naples. He received his

early training from his father Angelo, later by Francesco de Maria

and Giacomo del Po. By around 1700, he became the head of a

famous painting school81. He developed his own style, characterized

by brownish shadows, which is indebted to Giovanni Lanfranco and

Mattia Preti. Shadow and light and the clarity of line are typical,

even when the figures are nearly conventional82. He had patrons

like Prince Eugene of Savoy and the French king Louis XIV83.

Among his pupils were among others Paul Troger, Daniel Gran.

Apart from a visit to Rome he never left the kingdom of Naples,

but nevertheless he acquired an international reputation, as Pisani

shows very clearly in his article84. He was still famous at the end

of the eighteenth century, when students of painting visited Naples

and painted after him85. Solimena first came into contact with the Jesuits at the age of

twenty86, the illustrations for the Halieutica of 1689 were not his

first for Giannettasio. Together with Louvemont, he had already

created ten illustrations for the Piscatoria et nautica in 168587. He

is also known to have created paintings on mythological subjects,

including an oil-on-canvas scene of Aurora taking leave of Tithonus88,

executed in 1714. 80 Pisani (2002: 69 with n. 105); Santoro-Segatori (2013: 191-192).

81 For his life see Bologna (1958: 177-201); Pisani (2002: 44-56); Hojer (2011: 11), Stone (1997: 21-23). For his connection to the Accademia dell’Arcadia

see Lotoro (2016: 119-122).

82 View for his metaphorical imagery Pisani (2002: 56-61).

83 J. P. Getty Museum site: http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artMakerDetails?maker=762&page=1; Pisani (2002: 43).

84 Pisani (2002: 43).

85 Walch (1979: 247-248).

86 Pisani (2002: 45), frescoes in the Capella di Sant’Anna in the Gesù Nuovo church, Naples in 1677; Bologna (1958: 180; 259).

87 Bologna (1958: 181; 284). Solimena also worked together with the engraver Andrea Magliar (fl. c. 1690) decorating the books Universalis Geographiae

Elementa (Napoli 1692) and the Bellica (Napoli 1699).

88 Oil on canvas 1714, Los Angeles, The J. P. Getty Museum (84.PA.65) http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/artObjectDetails?artobj=856&handle=li

[2023-05-25]

89 Rodini (2000:70).

The pearl was interpreted as a divine gift, symbolizing purity

and chastity, with its formation attributed to dewdrops descending

from the moonlit heavens. Within Christian allegorical tradition,

the pearl became emblematic of the Virgin Mary or Christ, while the

dewdrops were analogized to the Holy ghost and the Immaculate

Conception of Mary. The precious and shimmering pearls are

also used in art to decorate crucifixes89 and as jewellery for Mary.

Solimena’s artistic representation features a radiantly haloed figure,

deliberately ambiguous in its iconography to allow interpretation

as either the Virgin Mary or the dawn goddess Aurora. Far from being confined to his Jesuit90 environment,

Giannettasio also interacted with the ‘modern philosophers’91 of

counter-movements, such as the famous lawyer and ‘acknowledged

leader of the Neapolitan intellectual life in the 1680s and 1690s’

Giuseppe Valletta92. He was one of the founders of the Accademia

degli Investiganti, some of its members were accused of atheism

and heresy. His huge private library (18.000 books) was famous

in Naples and often used by his friends, even from abroad, and a

meeting point for intellectual life. Valletta also established a chair in

Greek at the University of Naples because of his own knowledge of

and strong interest in the language93. Giannettasio even dedicated

some pages of his Historia neapolitana to Valletta, and also made

his friend the protagonist of his eclogue Antigenes, the third in the

collection Piscatoria. The argumentum of the 1715 edition explains

that of the two protagonists, Antigenes represented Valletta and

Argilochus the artist Francesco Solimena (1657-1747): Per Antigenem intellegit poeta familiarissimum suum Josephum

Vallettam jurisconsultum eximium, & Latinis, Graecisque litteris

florentissimum,…, per Argilochum innuit Franciscum Solimenam,

pictorem sui temporis egregium, antiquis ipsis vel invidendum,

Musisque Ethruscis perpolitum. (‘By Antigenes, the poet understood

his very close friend Giuseppe Valletta, an excellent lawyer, who

was very famous for his knowledge in Latin and Greek letters, …,

by Argilochus he indicated Francesco Solimena, a distinguished

painter of his time, to be envied even by the painters of antiquity,

very accomplished in Tuscan Muses’)94. Valletta as a member of the Accademia degli Investiganti95 was

involved in a trial concerning the ‘affair of the atheists’ starting

at the end of the 1680s. He published these matters not only in a

letter to Pope Innocent XII (1693), but also in his Istoria filosofica

(c.1704), for which he and the leaders of the Accademia were

attacked by the prefect of the Jesuit school in Naples96. Among them

was another patron of Giannettasio, the wealthy Neapolitan Carlo II

de Cardine97, who is addressed in the tenth book of the Halieutica98.

Giannettasio himself does not seem to have ever been directly

involved in this trial99. However, these events may have played a

role in Giannettasio’s decision to leave Naples at the age of 57 years

in 1705 and to withdraw from teaching to the Villa Cocomella near

Sorrento. 90 On the general history of the Society of Jesus, see Bangert (1986²); O’Malley (2000 [repr.]).

91 See for the discussion about the ‘modern philosophers’ at this time in Naples, Robertson (2005: 97-99).

92 Giuseppe Valletta (1636-1714) member and one of the founders of the Accademia degli Investiganti, wrote an Istoria filosofica (1703-04). See Piaia

(2011: 246-249).

93 Stone (1997: 2), he had a remarkable collection of Greek vases too; Piaia (2011: 246-247).

94 See Giannettasio, Piscatoria et nautica (1685: 13), see Stone (1997: 20-21), who stresses that the pairing of both “indicates the connections between

intellectuals and artists”; Bologna (1958: 181).

95 Accademia degli Investiganti was closed after the trials against the Atheists (reopened only for a short period in 1735-1737), see Galera Gomez the

chapter “Los investigadores” (2003: 81-127, especially 103, n. 317).

96 The others accused included Leonardo di Capua, Luc’Antonio Porzio and Francesco d’Andrea, see Robertson (2005: 98). For the “affair of the

atheists” see. Robertson (2005: 98-101), Wright (2013: 134), Piaia (2011: 249-250, 266); Osbat (1974: 11-12; 450-69).

97 Cardine, or Carlo II de Cárdenas (d. 1694), from a noble Neapolitan family was a generous friend of Giannettasio, Grant (1965: 248); Schindler

(2003:297). Another one is the archbishop and Cardinal of Naples Giacomo Cantelmo (1665-1702), see Comparato (1975: 267-271), whom he dedicated

the 13th eclogue of his piscatoria, Grant (1965: 376); Schindler (2003: 294). He took part in the trial against the Ateisti, see Nuzzo (2008: 194).

98 Giannettasio, Hal. 10, p. 1 Cardenide, nostris semper memorande Camoenis (“Cardine, you who is always in our Muses’ minds”); he mentions him

also in the Piscatoria, ecl. 14 Cardenides (“descendents of Cárdenas,” 114 verses).

99 Robertson (2005: 98) points out that in the 1690s the prefect of the Jesuit school in Naples Giovan Battista de Benedictis had at the same time to

defend the Jesuits against the hostilities of the Jansenists. According to Nuzzo (2003: 192-194) Giannettasio was indirectly involved in the conflict

between de Benedictis and Leonardo di Càpua (1617-1695), a founder of the Accademia degli Investiganti and defender of the Cartesian method. At

the same time an anonymus Francesco wrote a Dialogue Giannettasius vel de animarum transmigratione Pythagorica (ed. first by Luigi de Franco,

Firenze 1978), where Giannettasio was one of the interlocutors, see the discussion Stone (1997: 61-63 with n. 20). This myth of Drymo and Aurora is representative of the Early

Modern practice of altering classical myths and composing new

ones. From Boccaccio onward, the authors of the Renaissance,

whether clerics or laymen, began to imitate and tried to excel

the famous authors of antiquity with their new creative poetry.

Unfortunately, it is rarely possible to prove how this neomythological

literature directly influenced or was influenced by

new trends in music and art. The Jesuit teacher Giannettasio is a

very late example in the time of Enlightenment, a man who tried

to emulate both Antiquity and the poetry of a hundred years

earlier, in an old-fashioned but creative and playful way. To this

end, he situated the aforementioned myth within the challenging

and complex genre of didactic poetry, thereby demonstrating

Jesuit erudition. While the pearl has held allegorical significance

in Christian tradition since its biblical mention (Matthew 13:45–

46) and later evolved into a symbol of the Virgin Mary’s chastity

and purity, Giannettasio’s work conspicuously avoids engaging

with this hermeneutic framework. Neither does he incorporate

Christian allegorical or moralistic exegesis reminiscent of 12thcentury

Renaissance interpretive practices. Instead, his approach

remains firmly anchored in classical traditions and the neoclassical

poetics of his Renaissance predecessors, such as Giovanni Pontano

and Jacopo Sannazaro. Though Naples was affected by a plague epidemic, an agrarian

crisis and a decline of trade in southern Italy, the internal difficulties

between the Atheists and the inquisition, and finally the struggle

against occupation during the Spanish War of Succession, its

scientific and cultural life was still lively and fruitful. This ambiguity

in his poetry, which evokes an unreal world of myth and a locus

amoenus while eschewing political realities, positions his oeuvre

as a vehicle for escapism from the actual conditions of his time.

With this mythological didactic poem, versified by Giannettasio and

visually interpreted by Solimena, we encounter the rare instance

in which literary text and work of art were conceived almost

simultaneously; this refined decorative engraving thus not only

corresponds to but also accentuates Giannettasio’s literary creation

(Figure 2). None No conflict of interest.Giannettasio’s Version of Aurora

Foot Notes

Foot Notes

Giannettasio’s Version of Aurora in Art

Foot Notes

Christian Allegorical Interpretation of the Pearl

Giannettasio’s Heterodox Circle of Friends and his

Sphere of Influence

Foot Notes

Acknowledgement

Conflict of Interest

References

- Bostock, John Riley, H. T. (1855) The Natural History of Pliny vol. 2. London: Bohn.

- Bungies, Wolfgang, Heinekamp, Albert (1990) Wilhelm Gottfried Leibniz. Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe, Reihe 1 Allgemeiner, politischer und historischer Briefwechsel Bd. 12. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- Collegio Societas Iesu (1599) Ratio atque institutio studiorum Societas Iesu. Neapoli (Naples): Longhi (Longo).

- Gädeke, Nora, Van den Heinzel, Gerd (2001) Wilhelm Gottfried Leibniz. Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe, Reihe 1 Allgemeiner, politischer und historischer Briefwechsel Bd. 17. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

- Nash, Ralph (1996) The Major Latin Poems of Jacopo Sannazaro. Translated into English prose with commentary and selected verse translation. Detroit: Wayne State Univ. Pr.

- Nash, Ralph (1966) Arcadia & Piscatorial Eclogues. Translated with an introduction. Detroit: Wayne State Univ.

- Putnam, Michael C. J. (2009) Latin Poetry (The I Tatti Renaissance Library 38). Cambridge/ Ma.:Harvard Univ. Pr.

- (1722) Nicolai Parthenii Giannettasii Neapolitani e societate Jesu Annus eruditus in partes quatuor seu stata tempora distributus, Neapoli: Apud Dominicum Raillard.

- (1689) Nicolai Parthenii Giannetasii neapolit. Soc. Jesu Halieutica, Neapoli: ex officina Jacobi Raillard.

- (1715) Nicolai Parthenii Giannettasii neapolitani e societate Jesu Opera Omnia Poëtica, tomus secundus complectens Piscatoria, Nautica, et Halieutica, Neapoli: apud Bernardum-Michaelum Raillard.

- (1685) Nicolai Parthenii Giannettasii neapolit. Soc. Jesu Piscatoria et nautica, Neapoli: Typis regiis.

- Scheel, Günter, Müller, Kurt, and Gerber, Georg (1970) Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Allgemeiner politischer und historischer Briefwechsel 1692.Bd. 8. Bd. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- Utermöhlen, Gerda, Scheel, Günter, and Müller, Kurt (1979) Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Allgemeiner politischer und historischer Briefwechsel 1694 Bd. 10. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- Bangert, William V. (1986). A History of the Society of Jesus (The Institute of the Jesuit Sources, 3, 3). St. Louis: Institute of Jesuit Sources.

- Bartley, Adam Nicholas (2003) Stories from the Mountains, Stories from the Sea. The Digressions and Similes of Oppian’s Halieutica and the Cynegetica (Hypomnemata 150). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Berggren, John L., Jones, Alexander (2001) Ptolemy’s Geography: An Annotated Translation of the Theoretical Chapters. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Pr.

- Bologna, Ferdinando (1958) Francesco Solimena. Napoli: L’arte tipografica.

- Colonna, Aristide (1963) Il commento di Giovanni Tzetzes agli ‚Halieutica‘ di Oppiano. Lanx satura N. Terzaghi oblate. Miscellanea philological. Genova: Univ. di Genova, pp. 101-104.

- Comparato, Vittor I. 1970 (repr. 1988) Giuseppe Valletta. Un intellettuale Napolitano della fine del Seicento. Napoli: Istituto Italiano per gli studi Storici.

- Comparato, Victor (1975) Cantelmo, Giacomo. Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani Roma: Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, pp. 267-271.

- Fajen, Fritz (1999) Oppianus Halieutica. Einführung, Text, Übersetzung in deutscher Sprache, ausführliche Kataloge der Meeresfauna. Stuttgart-Leipzig: Teubner.

- Friedrich, Markus (2022) The Jesuits. A History. Princeton-Oxford: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Füssli, Johann R (1816) Allgemeines Künsterlexikon, oder kurze Nachricht von den Leben und Werken der Maler, Bildhauer, Vol. 2. T-Z. Zürich: Orell, Füssli.

- Galera Gómez, Andres (2003) Ciencia a la sombra del Vesubio. Ensayo sobre el conocimiento de la naturaleza. Madrid: Solana e Hijos.

- Grant, William Leonard (1957) New Forms of Neo-Latin Pastoral. Studies in the Renaissance 4: pp. 71-100.

- Grant, William Leonard (1965) Neo-Latin Literature and the Pastoral, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Harrauer, Christine, Hunger, Herbert (2006) (9th edn.), Lexikon der griechischen und römischen Mythologie: mit Hinweisen auf das Fortwirken antiker Stoffe und Motive in der bildenden Kunst, Literatur und Musik des Abendlandes bis zur Gegenwart. Purkersdorf: Hollinek.

- Haskell, Yasmin A. (2003) Loyola’s Bees. Ideology and Industry in Jesuit Latin Didactic Poetry. Oxford, New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Haskell, Yasmin (2007) Poetry or Pathology? Jesuit Hypochondria in Early Modern Naples. Early Science and Medicine 12(2): pp. 187-213.

- Haskell, Yasmin, Hardie, Philipp (1999) Poets and Teachers: Latin Didactic Poetry and the Didactic Authority of the Latin Poet from the Renaissance to the Present. (Proceedings of the Fifth Annual Symposium of the Cambridge Society for Neo-Latin Studies, Clare College, Cambridge, 9-11 September). Bari: Levante.

- Haye, Thomas (1997) Das lateinische Lehrgedicht im Mittelalter. Analyse einer Gattung. Leiden-New York-Köln: Brill.

- Hofmann, Heinz (1988) Das Neulateinische Lehrgedicht. Acta Conventus Neo-Latini Guelpherbytani. Proceedings of the Sixth International congress of neo-Latin Studies, Wolfenbüttel 12 August to 16 August 1985. Ed. Stella P. Revard et alii. Binghamton, N.Y.: CEMERS.

- Iapelli, Filippo (2003) Da residenza gesuitica a grande albergo, La Columella. Societas: Rivista dei Gesuiti dell’ Italia Meridionale 5(6): pp. 247-257.

- Keydell, Rudolf (1937) Oppians Gedicht von der Fischrei und Aelians Tiergeschichte. Hermes 72(4): pp. 411-434.

- Lach, Donald F., Van Kley, Edwin J. (1998) Asia in the Making of Europe. Vol. 3. A Century of Advance. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press.

- Leverenz, Lynn (1995) Four Manuscripts of Unattached Scholia on Oppian’s Halieutica by Andreas Darmarios. Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 36: pp. 101-114.

- Loach, Judy 2006 (repr. 2007) Revolutionary Pedagogues? How Jesuits Used Education to Change Society: The Jesuits II. Cultures, Sciences and the Arts 1540-1773. O’Malley et al. (Ed.s), Toronto: Univ. Press, pp. 66-85.

- Lotoro, Valentina (2016) ’Pittore degnissimo, & eruditissimo letterato’. La grafica di Francesco Solimena. Il capitale culturale 13: pp. 117-152.

- Martuscelli, Domenico (1816) Biografia degli uomini illustri del regno di Napoli. Napoli: N. Gervasi.

- McNaspy, Clement (2001) Teatro jesuita. Diccionario Histórico de la Compañía de Jesús, Vol.4. Ed. Charles E. O’Neill, Joaquin M. Domínguez. Madrid: Univ. Pontificia Comillas, pp. 3708-3714.

- Mazzarella da Cerreto, Andrea (1816) Niccolo’ Partenio Giannettasio. Biografia degli uomini illustri del regno di Napoli. Ornata de’ loro rispettivi ritratti. Compilata da diversi letterati Nazionali. Napoli: Nicola Gervasi, p. 5.

- Navarro Antolín, Fernando (2023) Navigación al extremo oriente (Nautica VIII, Nápoles, 1685-1686) Niccolò Partenio Giannettasio, S.J. Huelva: Univ. de Huelva.

- Nuzzo, Enrico (2003) Gli occultamenti dell’’Io’ e il tempo della Guerra. La vita di D. Andrea Cantelmo di Leonardo di Capua. Autobiografia e filosofia. L’esperienza di Giordano Bruno. Atti del Convegno. A cura di Nestore Pirillo. Roma: Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura.

- O’Malley, John W. (2000) (repr.). Introduction: The Historiography of the Society of Jesus: Where does it stand today? The Jesuits: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540-1773. Ed. O’ Malley et alii. Toronto a.o.: Univ. of Toronto Press, pp. 3-37.

- O’Malley, John W. (2007) Introduction: The Pastoral, Social, Ecclesiastical, Civic, and Cultural Mission of the Society of Jesus. The Jesuits II: Cultures, Sciences, and the Arts, 1540-1773. Ed. O’ Malley et alii. Toronto a.o.: Univ. of Toronto Press, pp. XXIII-XXXVI.

- Musi, Aurelio (2013) Political History. A Companion to Early Modern Naples. (Brill’s Companion to European History Vol.2) ed. by Tommaso Astarita (Eds.), Leiden: Brill, pp. 131-151.

- Osbat, Luciano (1974) L’inquisizione a Napoli. Il processo agli ateisti, 1688-1697 (Storia e politica, raccolta di studi e testi 32). Roma: Edizioni di storia.

- Piaia, Gregorio (2011) Giuseppe Valletta (1636-1714). Models of the History of Philosophy. vol. 2 From the Cartusian Age to Bruckner. Gregorio Piaia, Giovanni Santinello (Eds.). International Archives of the History of Ideas. Heidelberg a. o.: Springer, pp. 246-268.

- Pisani, Salvatore (2002) ’Ce peintre étant un peu délicat…’: Zur europäischen Erfolgsgeschichte von Francesco Solimena. Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 65,1: pp. 43-72.

- Prasad, Ram Chandra (1980) Early English Travellers in India. a Study in the Travel Literature of the Elizabethan and Jacobean Periods with particular reference to India: a Study Motilal Barnarsidass, Delhi.

- Rodini, Elizabeth (2000) Baroque Pearls. Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 25(2): pp. 68-71,106.

- Roellenbleck, Georg (1975) Das epische Lehrgedicht Italiens im fünfzehnten und sechzehnten Jahrhundert. Ein Beitrag zur Literaturgeschichte des Humanismus und der Renaissance. München: Fink.

- Robertson, John (2005) The Case for the Enlightenment. Scotland and Naples 1680-1760 (Ideas in Context). Cambridge a. o.: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Santoro, Marco, Segatori, Samanta (eds.) (2013). Mobilità dei mestieri del libro tra quattrocento e seicento. Convegno internazionale Roma, 14-16 Marzo 2012 (Biblioteca di “Paratesto 8). Roma-Pisa: Fabrizio Serra Editore.

- Schindler, Claudia (2001) Nicolò Partenio Giannettasios Nauticorum libri VIII. Ein neulateinisches Lehrgedicht des 17. Jahrhunderts. Neulateinisches Jahrbuch 3: pp. 145-176.

- Schindler, Claudia (2002) L’invenzione della realtà. Brani biografici e storici presenti nei poemi didascalici di Nicolò Partenio Giannettasio(1648-1715). Studi Umanistici Piceni 22: pp. 245-260.

- Schindler, Claudia (2003) Vitreas Crateris ad undas. Le egloghe piscatorie di Nicolò Partenio Giannettasio (1648-1715). Studi Umanistici Piceni 23: pp. 293-304.

- Schindler, Claudia (2014) Wissen ist Macht. Nicolò Partenio Giannettasio (1648-1715) und die neulateinische Gelehrtenkultur der Jesuiten in Italien. Scientia Poetica 18(1): pp. 28-59.

- Schindler, Claudia (2016) Exploring the Distinctiveness of Neo-Latin Jesuit Didactic Poetry in Naples: The Case of Niccolò Partenio Giannettasio. Exploring Jesuit Distinctiveness. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Ways of Proceeding within the Society of Jesus. Jesuit Studies 6. Robert A. Maryks, Leiden (Eds.), Boston: Brill, pp. 24-40.

- Schinosi, Francesco (1711) Istoria della Compagnia di Giesù appartenente al Regno di Napoli. 2, Napoli: Mutio.

- Stone, Harold S. (1997) Vico’s Cultural History. The Production and Transmission of Ideas in Naples, 1685-1750 (Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History vol. 73), New York-Köln: Brill.

- Tarzia, Fabio (2000) Nicola Partenio Giannettasio. Dizionario biografico degli Italiani, 54: pp. 448-449.

- Thieme, Ulrich Thieme, Felix (1992) Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon der Bildenden Künstler von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart. München: Deutscher Taschenbuchverlag. Leipzig: Seemann Verlag.

- Walch, Peter (1979) Foreign Artists at Naples: 1750-1799. The Burlington Magazine 121: p. 913.

- Wellmann, M. (1895) Leonidas von Byzanz und Demostratos. Hermes 30(2): pp. 161-176.

- Wright, Anthony D. (2013) Early Modern Papacy. From the Council of Trent to the French Revolution 1564-1789. Oxon-New York: Routledge.

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

-

Petra Aigner*. Aurora’s Pearls. Niccolo Giannettasio’s Variant of the Classical Myth of Eos. Iris On J of Arts & Soc Sci . 2(4): 2025. IOJASS.MS.ID.000543.

-

Aurora’s Pearls, Jesuit Niccolò Giannettasio, Cosmography, Geography, Didactic Latin Poem Halieutica

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- The Didactic Latin Poem Halieutica (Naples 1689)

- Aurora in Antiquity

- Giannettasio’s Version of Aurora

- Giannettasio’s Version of Aurora in Art

- Christian Allegorical Interpretation of the Pearl

- Giannettasio’s Heterodox Circle of Friends and his Sphere of Influence

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgment

- Conflict of Interest

- References