Review Article

Review Article

Post Blunt Trauma Suffering and the Need for Care and Caring

Louis D Filhour PhD, RN*

Albany Medical College, Albany Medical Center, Albany, New York, USA

Louis D Filhour PhD, RN, Albany Medical College, Albany Medical Center, Albany, New York, USA.

Received Date: September 03, 2019; Published Date: September 18, 2019

Introduction

As a hospital-based healthcare provider, you find yourself needing to care for a patient who has just experienced blunt trauma. For many patients, this is their first significant injury and experience of hospitalization. As the healthcare provider, do you know how your patient is suffering? Do you understand why your patient is suffering? Do you know if your patient is aware of his or her own suffering? And, importantly, do you know how your care can make your patient’s suffering better or even worse? This work describes the concept of suffering and two studies conducted to help gain an understanding of how and why patients experience suffering. The results of the studies identified the importance of the patient feeling cared about emotionally, socially, and spiritually as they are being cared for physically to help them better bear their suffering, find meaning in it, and be transformed by it. Examples are given reflecting how healthcare providers can make suffering better or worse for their patients through their care and caring. Understanding the experience of suffering is fundamental if healthcare providers hope to help their patients find meaning and regain their lost sense of wholeness.

Background/Significance

Human beings, as integrated bio-psycho-social-spiritual beings, dynamically interact with their environment [1,2]. Their sum is greater than their parts reflective of their unity [3]. Dynamic interaction with the environment may be positive or negative, influencing man’s ability to maintain a sense of wholeness and health [4]. Blunt trauma alerts life because it results in the victim’s perceived or real loss of wholeness, revealing itself as suffering [5].

Individuals worldwide can be victims of blunt trauma, regardless of socioeconomic status, occupations, or where they live [6]. Occurring more frequently than penetrating trauma, blunt trauma is more likely to impact multiple organ system, making it a serious injury [7]. National trauma data for 2016 demonstrated blunt trauma as the result of a fall or motor vehicle accident accounted for 62% of all traumatic mechanisms of injury for males and 83% for females with 87% of all trauma events being unintentional [8].

Blunt trauma results in experiences of suffering. Suffering is a complex, unique and subjective human experience, resulting from a perceived or actual threat of one’s sense of wholeness [9- 11]. While healthcare providers such as nurses and physicians share a desire to relieve suffering, the phenomenon of suffering is poorly understood by providers and frequently not viewed by them in relation to the sufferer’s lost sense of wholeness [12,13]. Technological advancements permit more victims to survive blunt trauma events, subsequently extending experiences suffering for longer periods [14]. Although a focus of health care and a motive for nursing care, there is inadequate knowledge about suffering resulting in a lack of effective nursing care interventions to address it [15]. Human beings manage their suffering by finding meaning in it and nurses can assist them with that process [16]. Because of its prevalence and significance, suffering by victims of blunt trauma is an important issue for nurses and serves as the focus of these phenomenological studies.

Purpose

Nursing philosophy should guide practice, enhanced and developed through acquisition, substantiation, and verification of nursing knowledge [17,18]. The experience of suffering results in a need for care and caring, making the phenomenon of suffering important to nursing’s philosophy. “The living experience of suffering is an important phenomenon of interest to be studied”. Little research has focused on patient’s suffering and the nursing care to alleviate it [19]. Research is needed to provide knowledge and understanding to guide providers in recognizing and addressing patient suffering [20,21] first studied the lived experience of suffering by male victims of blunt trauma, replicating study with female victims in 2018 [22]. The results of these two studies are presented in this work.

Nurses could assist patients make suffering bearable or alleviate it by helping them find meaning in it. However, if nurses are unable to view patients holistically, their ability to identify patients’ existential suffering is decreased, resulting in a lack of caring and neglect. Failure by nurses to recognize and address more than physical needs increases their patients’ risk for additional or avoidable suffering. Holistically caring for and about their patients empowers nurses to address various forms of suffering such as anxiety, stress, pain, fear, confusion, isolation, loss of control, and despair.

Research question

What is the lived experience of suffering for adult males or females who survived three to 12 months after the life-impacting event of blunt trauma served as the research question for these two studies? Sub-questions can refine the central question and help provide specificity [23]. Sub-questions for these studies addressed: How or in what forms did participants suffer? What made their suffering more bearable or unbearable? How were they transformed by their suffering?

Methods

Using a phenomenological approach, two studies were conducted, one with 17 men and the other with 11 women, all of whom having had a blunt trauma event in the previous six to 12 months. Participants were recruited using the registry of a Level 1 trauma hospital following investigation approval by the hospital’s IRB. Participation was voluntary, and no compensation was provided. Interviews, using questions previously provided to participants, were recorded so they could be transcribed verbatim, allowing participants to review and revise to ensure the transcription documents reflected their experiences. Validated transcriptions were then used for data analysis following steps suggested by Cohen, Kahn, and Steeves [23] based on the work [24]. NVivo software was used to facilitate the coding process [25].

Coding followed by the reduction process resulted in experiences of suffering clustering into five groups: physical, emotional, social, economic, and spiritual. While not a conscious act, the researcher’s clustering aligned with nursing’s concept of man possessing wholeness: unitary, integrated bio-psychosocial- spiritual beings. Examples of things which made suffering more or less bearable clustered into factors intrinsic or extrinsic to participants. Themes developed through further data analysis were shared with participants for feedback and validation. Having participants validate the proposed themes helped to ensure the themes reflected meaning participants gave their lived experiences of suffering [26]. Twenty-six of 28 participants returned their reviews, all validating the proposed themes.

Results

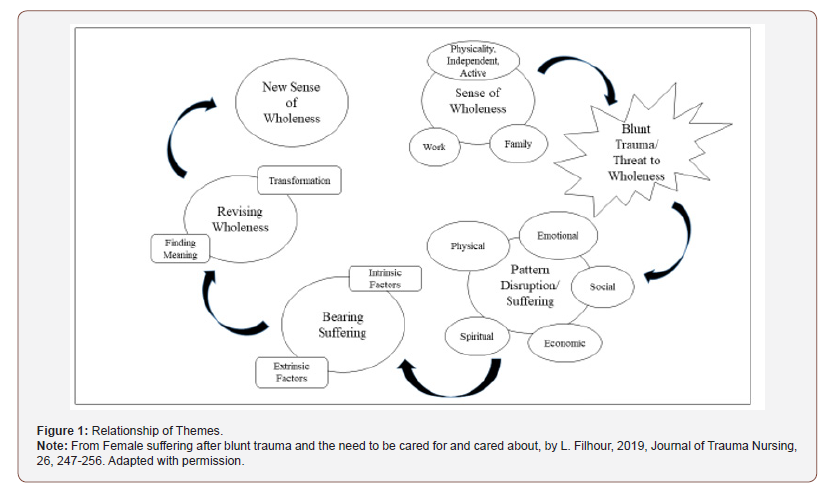

Validated themes were the same from both studies. Themes reflected participants’ (a) Perceived or real threat to their sense of wholeness, (b) Disruption of normal patterns manifested as suffering, (c) Regaining a sense of wholeness by bearing suffering, and (d) Revising a sense of wholeness by finding meaning in their suffering and thus being transformed by it. Subthemes for the “Threat to Wholeness” related to how participants defined themselves or their source of meaning: Physicality/Activity/Independence, Family, or Work. Subthemes for the “Pattern Disruption” reflected five forms of manifested suffering: Physical, Emotional, Social, Economic, and Spiritual. Subthemes for “Regaining Wholeness” were associated with intrinsic and extrinsic factors making suffering more or less bearable. Relationship of these themes is demonstrated in (Figure 1).

Theme 1: Threat to meaning and wholeness

Responses from the interview provided evidence as to how participants defined themselves; their meaning. Male participants found meaning through their physicality, families, or work. Female participants found meaning through their independence and activities, families, or work. Disruptions to normal patterns, in both studies, manifested experiences of physical, emotional, social, economic, and spiritual suffering. The journey to regain wholeness was helped or harmed by intrinsic and extrinsic factors, making suffering more or less bearable.

Theme 2: Pattern disruption and suffering

It is through dynamic interaction with their environment that human beings develop patterns reflecting mutual, simultaneous, and interactive processes [27]. The unintentional event of blunt trauma disrupts these patterns [5]. Suffering results because of the person’s perceived impending or actual destruction to his or her patterns or wholeness and continues until either the perceived threat passes or wholeness and pattern restoration is achieved through some other fashion [5,9].

Coding of participants’ pattern changes reflected experiences of suffering, which aligned with the concept of wholeness. Both studies found participants verbalized physical, emotional, social, economic, or spiritual pattern disruptions as experiences of suffering [5,22]. The forms of suffering were found through analysis to be interrelated and not mutually exclusive. Forms of suffering were also not experienced equally by all participants. Participants in both studies experienced mostly physical and emotional suffering, followed by social, economic, and spiritual suffering in that order.

Physical suffering: Physical suffering was the most frequently experienced form of suffering by all participants. For males, physical suffering clustered into five major types: pain, decreased activity tolerance, sleep disruption, memory loss, and constipation. For females, physical suffering clustered into five major types: decreased activity tolerance, pain, sleep disruption, constipation, and personal hygiene. Suffering related to a change in their decrease in activity was experience by all 11 participants. Both males and females identified physical suffering as contributing to emotional suffering in the form of depression and social suffering because decreased activity tolerance led to isolation.

Emotional suffering: Injuries decreased physically ability to do typical patterns of activities, thus decreasing the emotional joy normally experienced from doing those things, threatening participants’ senses of wholeness. For many participants, this blunt trauma event resulted their first experience with a significant, life altering injury. Unknowns about outcomes abounded, contributing to emotional suffering reported as worry, doubt, concern, or stress. Both male and female participants recognized and verbalized feelings of depression. They shared feeling demoralized, vulnerable, humbled, insignificant, frustrated, and disappointed, also reflecting emotional suffering. Both sexes reported behavioral changes including impatience and aggression.

Social suffering: Social suffering resulted from changes in previous patterns of social interactions. New interactions were experienced with hospital staff while previous patterns with spouses, children, other family members, friends, or acquaintances changed because of a change in roles, relationships, or ability to socialize. Injuries from blunt trauma forced participants to change their normal social role of caretaker to one needing care. Social suffering related to participants’ emotional suffering, not wanting to be a burden to others. Dependence on others was the most frequently reported form of social suffering.

A perception of not being listened to by hospital staff resulted in participants not only experiencing social suffering, but also emotional and at times physical suffering. “Good friends” who failed to help when needed also resulted in social and emotional suffering. The significant decrease in mobility negatively impacted previous levels of social interactions resulting in feelings of isolation or loneliness, contributing to the emotional suffering of depression. Some participants needed to change where they slept in their homes because of their physical limitations, which impacted socialization with their spouses.

Economic suffering: Economic suffering occurred because of decreases in income secondary to the inability to work because of the physical injuries, expenses not covered by insurance, or a lack of insurance. The high cost of the helicopter transportation not covered by insurance resulted in economic suffering, especially when the trauma victim had no input as to the choice of transportation. Economic suffering also contributed to emotional suffering by increasing doubt and worry about being able to pay the bills. Female participants acknowledged suffering because of additional uncovered expenses related to needed equipment at home to help with the recovery or extra expenses for childcare.

Spiritual suffering: Spiritual suffering, the least experienced form of suffering, reflected a threat to the participant’s normal state of spirituality. Only four male and three female participants reported experiences reflecting spiritual suffering. Participants suffered, questioning why their God would allow this to happen to them; “Why me?” Rather than a significant source of suffering, these studies found spirituality played a role in helping most participants better bear their suffering.

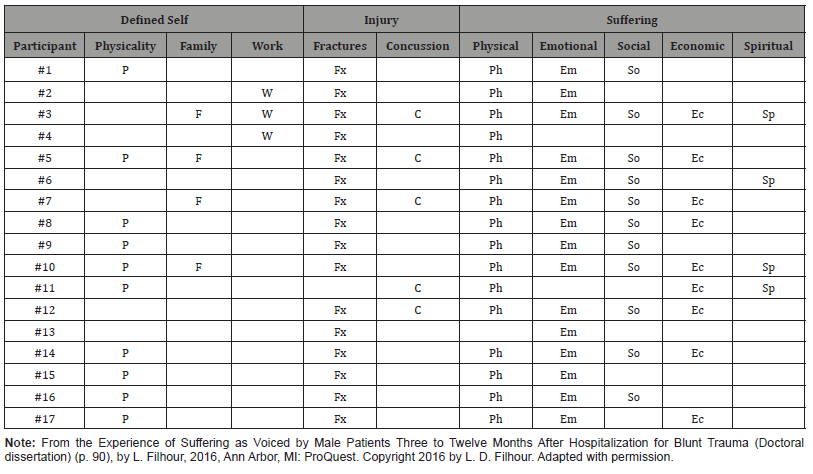

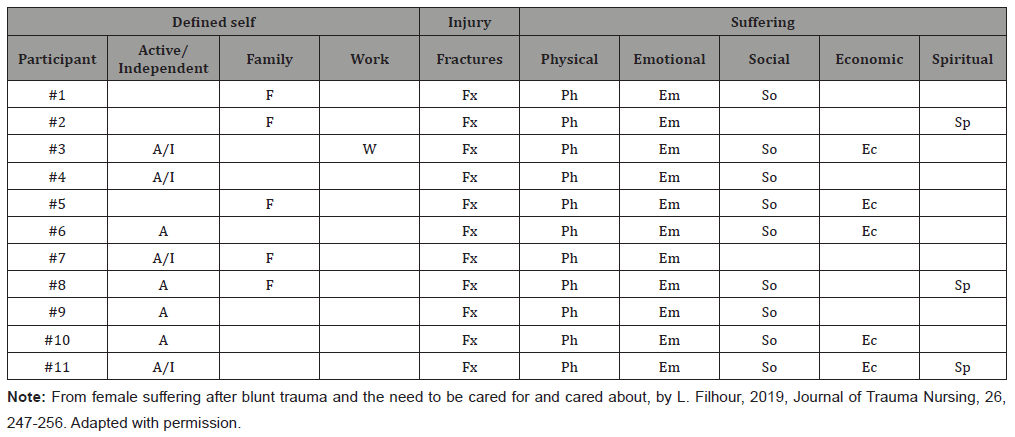

Summary of suffering: (Table 1) lists information on male participants and (Table 2) on female participants. Pattern changes contributed to experiences of suffering. How participants defined themselves, what gave them meaning, related to the forms of suffering they experienced. Deriving meaning from their physicality, activities, or independence, resulted in suffering because of their lost ability to do those things. If they derived their meaning from their role in relation to their family, then they suffered because of a change in that role, from caretaker to one in need of care. Defining themselves by their work resulted in suffering from the loss of that work. In all three of these situations, the participants suffered as a result of a loss of their meaning and sense of wholeness.

Table 1: Relationship Among Male Participants’ Self Definition, Injuries, and Forms of Suffering.

Table 1: Relationship Among Female Participants’ Self Definition, Injuries, and Forms of Suffering.

Physical suffering was most frequently verbalized by participants followed by emotional, social, economic, and spiritual. Analysis revealed the interrelatedness of the five forms of suffering rather than being mutually exclusive. For example, physical suffering such as pain and limited mobility underwrote emotional suffering of depression, social suffering because of decreased social interactions, economic suffering because of a decreased ability to work, and spiritual suffering as to how God could allow this to happen.

Theme 3: Regaining wholeness

Blunt trauma resulted in injuries that threatened participants’ sense of wholeness and meaning. These pattern disruptions manifested experiences of suffering: physical, emotional, social, economic, or spiritual. Recovery from physical injuries including healed fractures, resolved subdural hematomas, and decreased symptoms of their concussions, eventually reduced threats and helped them regain their sense of wholeness. However, the recovery process following blunt trauma required several months and care from others. Participants were asked during the interview process what made their suffering more or less bearable during this long recovery process. Analysis revealed factors intrinsic and extrinsic to participants. Intrinsic factors were found to make suffering more bearable. No intrinsic factors were identified making suffering unbearable. Some extrinsic factors were found to make suffering more bearable for participants, while others made it more unbearable.

Intrinsic factors: Intrinsic factors were related to the participant himself or herself. Key intrinsic factors identified through the analysis of the data included attitude, motivation, knowledge, control, and spirituality. These intrinsic factors enhanced participants’ ability to make suffering more bearable as they journeyed through the process of recovery, regaining wholeness and meaning.

A positive attitude and strong desire to get well was a significant intrinsic factor for many participants. Knowledge from previous experiences or newly acquired knowledge obtain from care providers helped participants regain control and better bear their suffering. Blunt trauma injuries exposed participants to unfamiliar experiences, resulting in a world of unknowns and loss of control. Participants were better able to bear suffering when they regained control by making decisions about their care. The intrinsic factor of spirituality was also found to help some participants better bear their suffering.

Extrinsic factors: Participants readily identified and shared extrinsic factors making their suffering more or less bearable, thus helping or impeding their recovery. The most important extrinsic factor was positive support provided by others: hospital staff, spouses, children, family, and friends. Because of their injuries, participants needed support in the form of physical care and emotional caring. They needed to be cared for to help make the physical suffering bearable and care about to make the emotional, social and spiritual suffering bearable. While positive support made suffering more bearable, negative or inappropriate support made it more unbearable. Inappropriate or total lack of physical or emotional care by others resulted in participants experiencing avoidable increases in physical, emotional, and social suffering.

Summary of regaining wholeness: Participants experienced threats to their sense of wholeness or meaning. These threats resulted in changes in their normal patterns which manifested experiences of physical, emotional, social, economic, and spiritual suffering. As bones mended and concussion healed during the lengthy recovery process, participants progressed toward regaining wholeness. These studies found their journeys were made easier by things that helped them to better bear their suffering and was made more difficult by things that increased their suffering. Positive intrinsic factors such as attitude and motivation to get well helped them to bear better their suffering. Participants’ knowledge, either from previous experiences or newly acquired, made suffering more bearable as well as helped them regain lost control, also making suffering more bearable.

Extrinsic factors such as positive support was essential in helping participants through their lengthy process of recovery and regaining wholeness. Beneficial support from others reflected physical caring for and emotional, social, economic and spiritual caring about the participant. Some extrinsic factors made suffering more unbearable, negatively impacting the participants’ journeys. Poor quality care or social interactions by healthcare providers were the most significant negative extrinsic factors. They were unbeneficial and did not reflect caring for or about participants, contributing to avoidable increased suffering.

Theme 4: Revising wholeness

Blunt trauma caused significant injuries threatening participants’ senses of wholeness and disrupting patterns resulting in experiences suffering. During the long recovery process, suffering was made more bearable by intrinsic and extrinsic factors, with positive attitude and motivation being the most important intrinsic factors while support and quality care were the most important extrinsic factors. Poor quality care or a lack of caring made suffering more unbearable.

The long recovery allowed time for participants to reflect on their experiences, which led to a transformation; a revised sense of wholeness. They recognized the fragility of life and their own vulnerability which served as the motivation for these transformations; a change in what they felt was important. Because of these new insights, participants changed their focus to more on today and less about the future while also reporting a decrease in risk taking and a greater focus on time with their families. For many participants, this was their first experience being significantly injured and someone in need of care. As a part of their transformation, many reported increased empathy for others with injuries or disabilities. Another common change included a slowing in the pace of their activities so that they could better appreciate “the little things.”

Recommendations for Nursing Practice

Hyatt, Davis and Barroso [28] identified knowledge of challenges and suffering experienced by patients following a significant injury is important if nurses are to promote care and caring in support of the patient’s need to regain wholeness. These studies add knowledge which can inform nursing practitioners. It provides knowledge about the human experience of suffering within the philosophy of nursing science and informs nursing practice on opportunities to relieve patient suffering.

Nurses must first understand a patient’s experience before they can develop new interventions and measures to address it [28]. These studies expand the understanding of the adult, blunttrauma patient’s experience of suffering and thus support the development of new interventions and measures. Use of strengthsbased nursing [30] can enable nurses to provide an environment of moral support, facilitating patient’s generation of self-awareness. This ethical practice of nursing care, using affective awareness and empathy, supports person-centered care which not only gives patients a sense of being cared for physically but also being cared about emotionally, socially and spiritually.

Suffering is important to nursing because it is a universally experienced phenomenon [16,31] caring human science theory offers a structure to guide nursing practice related to the experience of suffering. Watson’s [32-36] caring theory identifies the usefulness of the transpersonal caring relationship between the nurse and patient to protect, enhance, and preserve the patient’s wholeness [34]. Using a transpersonal caring relationship empowers nurses to help patients in their search for meaning to relieve suffering, achieve transformation, and restore or revise wholeness. Nursing’s role in helping patients through transpersonal caring to better bear their suffering aligns with the caring concepts proposed by Swanson and Eriksson [37,38].

Suffering is a motive for care and caring by nurses, with its main focus on helping patients realize relief. Suffering is a unique experience resulting from the personal meaning given by the patient [39]. It is imperative nurses understand and respect culturally held beliefs and values of their patients if they are to help them address their suffering because culture provides the foundation for the beliefs and values the patient uses to interpret their experiences and give it meaning [40,41].

Nurses own the quality of the care they provide and should role model the desired behaviors for other care providers. Poor quality care and a lack of caring at the hands of care providers can result in avoidable and increased patient suffering. The findings of these studies confirm the importance of listening fully to patients to understand the meaning they give their experiences and to use that understanding to guide the nursing care provided. By assisting patients with understanding their condition and care, nurses play an important role in helping them better bear their suffering. Nurses, by empowering their patients to make decisions about their care through strengths-based nursing, help patients regain control and reduce suffering. Using the human caring concepts by Watson [42,43], Swanson, or Eriksson [37,38] to guide practice, nurses can provide care and caring, reducing suffering while making the patient feel truly cared for and cared about.

Summary

Surviving blunt trauma resulted in participants confronting their own fragility and vulnerability. Participants struggled understanding the many changes and unknowns of their new world and trying to find meaning in it. Through needed supportive help of others such as healthcare providers, spouses, family, and friends, and their own cognitive processing, participants embarked of the journey of rebuilding their assumptive worlds. Poor quality care and a lack of caring needlessly increased participants’ suffering. Study findings suggest ways nurses can provide care and caring, reducing suffering while aiding healing and transformation. Aware of their new sense of vulnerability, participants transformed through meaning-making with a focus on their significance and worth, creating a revised sense of wholeness and meaning.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflict of interest.

References

- Deal B (2011) Finding meaning in suffering. Holistic Nursing Practice 25: 205-210.

- Fantus RJ, Fildes J (2003a) NTDB data points: The blunt majority? Bull Am Coll Surg 88(80029: 42.

- Parse RR (2014) The human becoming paradigm: A transformational worldview. PA: Discovery International, Pittsburgh, USA.

- American College of Surgeons (2016) Executive Summary, Committee on Trauma. NTDB Annual/Pediatric Report 2016. Chicago, Illinois.

- Eriksson K (1997) Understanding the world of the patient, the suffering human being: the new clinical paradigm for nursing to caring. Adv Pract Nurs Q 3(1): 8-13.

- Watson J (2005) Caring science as sacred science. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis, USA.

- Malpas J, Lickiss N (2012) Introduction: Human suffering. Perspectives on human suffering, New York, USA, p: 1-5.

- Ferrell BR, Sun V, RM Carroll-Johnson, LM Gorman, NJ Bush (2006) Suffering. In, Psychosocial nursing care along the cancer continuum (pp. 155-168). PA: Oncology Nursing Society Publishing Division, Pittsburgh.

- Eriksson K (2002) Caring science in a new key. Nurs Sci Q 15(1): 61-65.

- Watson J (1999) Nursing: Human science and human care, A theory of nursing. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett & National League for Nursing.

- Bender M, Feldman M (2015) A practice theory approach to understanding the interdependence of nursing practice and the environment: Implications for nurse-led care delivery models. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 38(2): 96-109.

- Chiu L (2000) Transcending breast cancer, transcending death: A Taiwanese population. Nurs Sci Q 13(1): 64-72.

- Cohen M, Kahn D, Steeves R (2000) Hermeneutic phenomenological research: A practical guide for nurse researchers. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Arman M, Rehnsfeldt A, Lindholm L, Harmin E, Eriksson K (2004) Suffering related to health care: A study of breast cancer patients’ experiences. Int J Nurs Pract 10(6): 248-256.

- Watson J (2002) Assessing and measuring caring in nursing and health science. New York, USA.

- Watson J (2008) Assessing and measuring caring in nursing and health science (2nd ), New York, USA.

- Cassell E J (1991) Nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. NY: Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Holt J (2014) Nursing in the 21st century: Is there a place for nursing philosophy? Nursing Philosophy 15: 1-3.

- Hyatt KS, Davis LL, Barroso J (2015) Finding the new normal: Accepting changes after combat-related mild traumatic brain injury. J Nurs Scholarsh 47(4): 300-309.

- Rehnsfeldt A, Eriksson K (2004) The progression of suffering implies alleviated suffering. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science 18: 264-272.

- Filhour LD (2016) The experience of suffering as voiced by male patients three to twelve months after hospitalization for blunt trauma (Doctoral Dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest. (Accession No. 1011617).

- Ploeg J (1999) Identifying the best research design to fir the question. Part 2: qualitative designs. Evidence Based Nursing 3: 36-37.

- Eriksson K (2007) Becoming through suffering-the path to health and holiness. International Journal of Human Caring 11: 8-16.

- Ferrell BR, Coyle N (2008) The nature of suffering and the goals of nursing. NY: Oxford University Press, New York, USA.

- Fantus RJ, Fildes J (2003b) NTDB data points: The critical aspect of blunt trauma. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons, 88: 43.

- Fawcett J, DeSanto-Madeya S (2013) Contemporary nursing knowledge: Analysis and evaluation of nursing models and theories (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis, USA.

- Baumann SL, Wright SG, Settecase-Wu C (2014) A science of unitary human beings perspective of global health nursing. Nurs Sci Q 27(4): 324-328.

- Paiva L, Rossi L, Costa M, Dantas R (2010) The experiences and consequences of a multiple trauma event from the perspective of the patient. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem 18(6): 1221-1228.

- O Mahoney C (2005) Widening the dimensions of care. Emerg Nurse 13(4): 18-24.

- Filhour LD (2019) Female suffering after blunt trauma and the need to be cared for and cared about. J Trauma Nurs 26(5): 247-256.

- Gottlieb LN (2014) Strengths-based nursing: A holistic approach to care grounded in eight core values. American Journal of Nursing 114: 24-32.

- Filhour LD (2017) The lived experience of suffering of males after blunt trauma: A phenomenological study. J Trauma Nurs 24: 193-202.

- Watson J, M. E. Parker (Ed.) (2001) Jean Watson: Theory of human caring. Nursing theories and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Davis, USA, pp: 343-354.

- Milton CL (2013) Suffering. Nursing Science Quarterly 26: 226-238.

- Rydahl Hansen S (2005) Hospitalized patients experienced suffering in life with incurable cancer. Scand J Caring Sci 19(3): 213-222.

- Scott P, Matthews A, Kirwan M (2014) What is nursing in the 21st century and what does the 21st century health system require of nursing? Nurs Philos 15(1): 23-34.

- Swanson K, AS Hinshaw, S Fleetham, J Shaver (1999) What is known about caring in nursing science? Handbook of Clinical Nursing Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp: 31-60.

- Van Manen M (1990) Researching lived experience. London, Ontario: University of Western Ontario, Canada.

- Watson J (1979) The philosophy and science of caring. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co, USA.

- Watson J (1985) Nursing: Human science and human care: A theory of nursing. CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts, Norwalk.

- Watson J (2012) Human Caring Science. A Theory of Nursing. MA: Jones and Bartlett, Sudbury.

- Yu A (2014) The encounter of nursing and the clinical humanities: Nursing education and the spirit of healing. Humanities 3: 660-764.

- QRS International (2018) NVivo.

-

Louis D Filhour PhD, RN. Post Blunt Trauma Suffering and the Need for Care and Caring. Iris J of Nur & Car. 2(2): 2019. IJNC. MS.ID.000532.

-

Blunt Trauma, Healthcare, Injury, Patients, Penetrating Trauma, Nursing’s Philosophy, Nurses, Phenomenological, Suffering, Emotional, Social, Economic, Physicality, Families, Emotional Suffering, Physical Suffering, Sleep Disruption, Memory Loss, Constipation

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.