Research Article

Research Article

Fulfillment of Informational Needs and Anxiety in High-Risk Pregnant Women Hospitalized for Preterm Birth

Ela Raizman*

Academic consultant, Department of Nursing, Hadassah Mt. Scopus University Hospital, Israel

Ela Raizman, Academic consultant, Department of Nursing, Hadassah Mt. Scopus University Hospital, Israel.

Received Date: September 24, 2019; Published Date: November 12, 2019

Abstract

Objective: Prenatal hospitalization of high-risk pregnant women is associated with numerous stressors. Effective antenatal education may be an important step in decreasing the perceived stress. Current study explores learning needs of high-risk pregnant women during a stressful period of antepartum hospitalization.

Design: Descriptive study.

Setting: The study was conducted in antepartum unit in a community hospital in Jerusalem.

Participants: Women considered at risk of preterm birth and hospitalized in the unit at least 48 hours.

Methods: Women were asked to fulfill Preterm Birth Learning Needs Questionnaire and State Trait Anxiety Inventory State form before and 24 hours after education session.

Results: Sixty women participated in the study. There was a significant difference between importance and fulfillment scores at total and all the domains of the learning needs. State Anxiety score was significantly lower after education session (43.60 (6.49)) than before (45.03 (5.33)) (p=0.045). Anxiety reduction was significantly correlated with the difference between importance and fulfillment of learning needs in total (r = -282, p<05), bio physiological (r = -319, p<05) and neonatal (r = -390, p<05) domains.

Conclusion: Hospitalized pregnant women have informational needs and seek more than factual information from healthcare providers.

Keywords: High-risk pregnancy; Hospitalization; Informational needs; Anxiety

Introduction

A pregnancy is considered high-risk when maternal or fetal complications that could affect the health or safety of either the mother or baby [1] are present. Management of pregnancy complications can involve activity restriction, bed rest and hospital stays extended sometimes until birth [2,3]. Antepartum hospitalization has been associated with a variety of physiologic, psychological and behavioral maternal and fetal adverse effects, and is often a negative experience for women [4,5]. A high-risk patient who is hospitalized antepartum may feel uncertain and tense about her pregnancy and the health of her fetus. Lack of information about her condition makes the situation even more complex and unpredictable [6].

High-risk pregnancy stress is often assessed through general measures of state anxiety and depressive symptoms [7,8]. Increased psychosocial anxiety has been demonstrated to contribute to poor pregnancy outcome [9,10].

Education is a core focus of patient-centered hospital care. Provided in different settings, education has been found to reduce patient anxiety in surgical procedures [11,12] and with oncology patients [13,14], imaging [15], prenatal counseling in low [16,17] and in high risk pregnancy. The purpose of patient education is to provide knowledge and skills, in order to empower the patient and increase his or her self-awareness [18]. For this kind of empowerment to succeed it is necessary to be aware of patients’ knowledge expectations and factors that influence them and also to be informed about the information that the patient has already received [19]. The aim of this study was to assess important educational needs in hospitalized pregnant women, to evaluate if these needs were fulfilled, and to explore if the need gap is related to patients’ characteristics and anxiety level.

Methods

The study was conducted in a 10-bed antepartum unit in a community hospital in Jerusalem that has over 5400 deliveries per year.

Participants

For the purpose of this study, a “high risk” pregnancy was defined as one between 18 and 36 weeks completed gestation with a diagnosis of any of the following: threatened preterm labor, preterm-premature rupture of membranes, cervical incompetence, placenta abruption, placenta previa, or preeclampsia. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Jewish women above 18 years old, hospitalized in the maternity unit for a minimum of 48 hours, considered at risk of either spontaneous or indicated preterm birth, had a singleton pregnancy with a gestational age ≤36 weeks, and with no previous history of psychiatric disorder.

The study protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Hadassah Medical Center. All participants in this study were informed about the scope and purpose of the study. Eligible women were also assured that the collected data would be used only for the purpose of the study, and that their decision to withdraw would not compromise the standard of the received care.

Women were approached individually, explained the purpose of the study and that it included a nurse-led education session. After agreeing to participate, a self-report Preterm Birth Learning Needs Questionnaire (PBLNQ) and State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) State form was administered to each subject. Every woman participated in the structured nurse-led educational program that includes all the topics mentioned in PBLNQ. 24 hours after participating in the education session, participants were asked to fill out the Fulfillment of Preterm Birth Learning Needs Questionnaire (FPBLNQ) together with the STAI-State form. To better understand the learning the needs of these women their prior relevant knowledge bases were measured before commencement of the educational session using PBLNQ [20], which consists of 18 topics commonly included in educational programs for women at risk for preterm birth. Respondents were asked to rate each topic on a continuum, from (1) “not very important to know” to (20) “very important to know” using a 20-point scale.

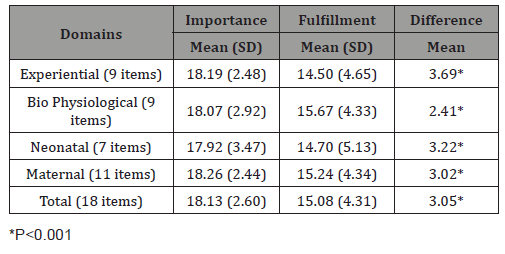

Fulfillment of the same needs was measured 24 hours after educational session using the same topics. Respondents were asked to rate each topic on a continuum, from (1) “not fulfilled at all during the education session” to (20) “very much fulfilled during the education session” using a 20-point scale. For the purposes of this study, we categorized learning needs into the bio-physiological (preterm labor, symptoms, treatment) and experiential (emotions and hospital experiences) domain as suggested by Leino-Kilpi and colleges [21], and maternal (issues of the pregnant women herself including preterm labor) and neonatal (issues of prematurity) domain as suggested by Petersen and colleges [22]. Reliabilities are presented in (Table 1).

Table 1: Reliabilities of study measures.

State anxiety was measured by the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)-State form developed by Spielberger [23]. State anxiety is defined as an unpleasant emotional condition that emerges in the case of threatening demands or dangers. The state scale consists of twenty items that ask people to describe how they feel at a particular moment in time rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1= not at all to 4= very much so; total scores for state anxiety range from 20-80, with higher scores indicating greater intensity of anxiety. The STAI has been validated in Hebrew and has been found to have satisfactory psychometric properties [24]. Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 was obtained in the present study. Basic demographic and medical information were collected and included: age, religion, marital status, level of education, employment status, pregnancy number, gestational age, parity, past preterm birth, living children, and complications during previous and/or current pregnancy.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS. In order to examine study measures reliabilities, Cronbach’s α was computes for PBLNQ and FPBLNQ total and each domain scores. Descriptive statistics, such as means, standard deviations, and frequencies, were used to present subjects characteristics. Means, standard deviations were used to present (F)PBLNQ individual items, total and domains scores. Pearson correlations were used to measure the associations between (F)PBLNQ individual items, total and domains scores.

One-way ANOVA were used to measure the associations between categorical and Pearson correlations between interval subjects characteristics and (F)PBLNQ total and domains scores, state anxiety score before and after educational session. In order to create new measures which expressed the difference between expected and fulfilled knowledge, FPBLNQ total and domains scores were decreased subsequently from PBLNQ total and domains scores. Change in state anxiety score was computed decreasing state anxiety score after educational session from state anxiety score before the session. Pearson correlations were used to measure the associations between these new variables. P-value of 0.05 was set as statistical significance.

Results

Sixty women took part in the study. The mean age of the participants was 32 (SD= 6.51 years). 48 (80%) of women were Israeli born, 36 (60%) considered themselves orthodox, while the rest defined themselves as traditional 13 (21.7%) or secular 11 (18.3%). Furthermore, 37 (62.1%) had academic degree, and 45 (75.9%) worked outside the home in paid employment. Gestational age ranged from 24 to 35 weeks with a mean gestational age of 29.5 weeks (SD = 3 weeks). For 18 (30%) of the women in the study, this was their first pregnancy, for 10 (16.7%) this was their second pregnancy and for 32(53.3%) this was their third or more pregnancy. 34 (56.7%) had children, 10 (16.7%) had experienced a previous preterm birth,18 (30.5%) had received preterm labor antenatal counseling.

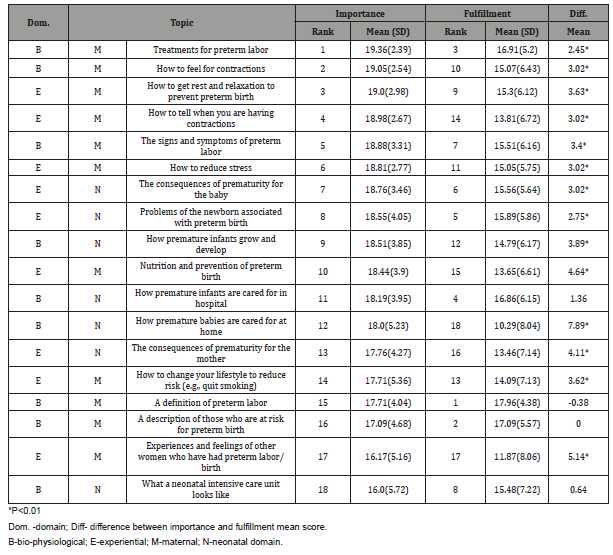

(Table 2) presents the pregnant women’s ranking of importance and fulfillment of their learning needs after the education session. (Table 3) presents descriptive statistics of difference and correlation of importance and fulfillment of learning needs in each domain. As can be seen in the table, there was a significant difference between importance and fulfillment scores at total and all the domains of the learning needs. Israeli born women showed higher scores of importance of learning needs in total (r = 0.31, p<0.05), biopsychological (r = 0.338, p<0.01), neonatal (r = 0.264, p<.05) and maternal (r = 0.306, p<.05) domains than of non-Israeli origin. Also, religious women showed lower scores of importance in bio physiological (r = -0.256, p<0.05) and neonatal (r = -0.273, p<.05) domains of learning needs than non- religious women.

Table 2: Importance and fulfillment of women` learning needs.

Introduction

Table 3: Scores of learning needs importance and fulfillment by domains.

No demographic and obstetric characteristics of the women in this study were found to be significantly correlated with fulfillment of learning needs in any domains.

STAI score was significantly lower after the education session (43.60 (6.49)) than before (45.03 (5.33)) (p=0.045), means reduction in state anxiety. The older the woman was, the lower was her STAI score before education session (r = -.292, p<.05). The higher the gestational age of pregnancy was, the lower was her STAI score after education session (r= -.269, p<.05). No significant difference was found between any demographic and obstetric characteristics and reduction in STAI scores of the women in the study. Reduction in STAI scores was significantly correlated with the difference between importance and fulfillment of learning needs scores in total (r= -.282, p<.05), bio physiological (r= -.319, p<.05) and neonatal (r = -.390, p<.05) domains.

Discussion

This current study explores the learning needs of highrisk pregnant women during a stressful period of antepartum hospitalization, which is associated with numerous strains, such as lack of activity, bed rest, tests and treatments, separation from family and home, boredom, feelings of uncertainty and lack of control [25,26].

Effective antenatal education which provides information that the patient wants, may be an important step in decreasing the perceived stress that hospitalized high-risk pregnant women face. Patient education begins with providing factual information to the patients, but also includes the interpretation and integration of information in such a manner as to bring about attitude or behavior changes that benefit a person’s health status [27]. Patient education is an essential nursing practice standard [28]. Richter et.al recommended that topics such as ways to reduce the side effects of prolonged bed rest, diagnostic tests, fetal development, and labor and delivery with a special emphasis on the unique differences of a premature birth should be included in the education of highpregnant women [29]. Education may include written material, supportive counseling and a tour of the nursery.

Women in this study rated each learning need as relatively important for them. Some women expressed that they wished to be told “everything.” The most important learning needs were ‘‘Treatments for preterm labor” and “How to feel for contractions”. The topics “How to get rest and relaxation to prevent preterm birth” and “How to tell when you are having contractions” were also rated as highly important. These priorities reflect women’s major concern regarding prevention of preterm labor.

Of the 18 items, “What a neonatal intensive care unit looks like” was rated as the least important learning topic. Women in this study considered “experiences and feelings of other women who have had preterm labor/birth’ relatively unimportant. It was rated as second from last. The maternal domain found to be more important than neonatal domain unlike the findings by Gupton & Heaman. Experiential and bio-physiological domains were rated at similar importance.

Motherhood is the chief ideological icon and primary identity for most Israeli women regardless of their education, employment or career aspirations. Leichtentritt et al. found that Jewish women with high risk pregnancies in an Israeli hospital expressed emotional ambivalence: women wanted to prolong the pregnancy as long as possible, while worrying about the health of the fetus and fearing giving birth to a disabled child, and at the same time wished to deliver as soon as possible. Women during high-risk pregnancy express feelings of responsibility for keeping the baby in as long as possible for the sake of their unborn child. They became much more conscious or aware of their body’s signals and are willing to cooperate with medical staff in order to deliver the baby as late as possible. [30-32].

The risk of preterm infants developing deficits and delays [33] are frequently explained during antenatal visits. Women have high expectations that modern technology and medical intervention can prevent preterm birth. These women recognize that compliance with odious and invasive treatments may increase the odds that their child will not be born prematurely. Israeli women hospitalized with high-risk pregnancy psychologically resist enforced medical compliance [34]. Although a majority of hospitalized women don’t continue their pregnancy until term, they are not prepared to discuss the possible complications of a premature birth.

“A definition of preterm labor” and “A description of those who are at risk for preterm birth” were the most fulfilled topics, while” How premature babies are cared for at home” and “ experiences and feelings of other women who have had preterm labor/birth” were the least. The bio physiological domain was fulfilled the most, while the neonatal domain the least. Even though spirituality and hope are essential to parents at risk of preterm labor, many health care providers view their main role as providers of factual information and inconsistently address social and parental issues. Gaucher found that women felt overall well informed; although 39% felt they received too much information [35].

“A definition of preterm labor”, “ A description of those who are at risk for preterm birth” and “ What a neonatal intensive care unit looks like”, “ How premature infants are cared for in hospital “, “ A description of those who are at risk for preterm birth “ were topics that their importance was the ranked the same as their fulfillment after the education session for women. Twelve topics were fulfilled significantly less than perceived being important. The only topic fulfilled significantly more than perceived being important was “A definition of preterm labor”.

Women’s educational needs were far from being fulfilled, at total and in all categories. Most high-risk pregnant women receive limited education while hospitalized [36]. Lack of information during prenatal care and unpreparedness for adverse effects may cause the fear of dying or losing their child [37]. In the Internet Era patients still have gaps in their informational needs. Faller et. al found that unmet information needs were prevalent in 36-48 % of cancer patients [38].

Discussions with healthcare providers is still an important source of information for pregnant women, while the internet plays a significant role in information seeking for less than half of the women [39]. Kraschnewski et. al also found that the internet cannot replace health care professional education during pregnancy [40]. In the current study we use State Anxiety to evaluate the stress level of high-risk pregnant women 48 hours after their hospitalization due to threaten preterm birth. The mean anxiety score was about 45 – while score over 40 point on moderate anxiety level [41].

Studies in different cultural settings found lower or higher [42- 44] anxiety level than our study has. In the current study anxiety level was found to be significantly related to age, with younger women being associated with higher anxiety level, similar to other researches [45]. Hospitalized patients experience physical and psychological stress, including high levels of anxiety and depression due to fears, worries, and uncertainties [46]. Anxiety level positively correlated with individual perception of risk [47].

In the current study education session influence the anxiety level- a more congruence between degree of importance and fulfilment in total, maternal and biophysical domains was, the greater was reduction of anxiety. Low satisfaction with informational support, unmet information needs in hospitalized pregnant women were related to higher anxiety and more depression symptoms [48]. Recent research in anxiety reduction in high-risk pregnant women concentrated in body-mind intervention to induce mental relaxation [49,50].

A recent review by Moreno-Peral found a small, but statistically significant benefit of educational and psychological interventions in prevention of anxiety [51]. Teaching content may not be assimilated until the patient’s anxiety is reduced [52,53]. The relationship between satisfaction with provided information and anxious symptoms might thus be bidirectional.

Limitation

Our study included Hebrew speaking hospitalized high-risk pregnant women only, without a control group of low-risk pregnant women or homebound pregnant high-risk women. We did not include spouses in this study. We measured anxiety by a general and not pregnancy-specific instrument as an expression of maternal distress, which is multidimensional. Anxiety symptoms decreased throughout the course of hospitalization due to pregnancy progression and the decreasing probability of fetal complications together with increase of positive effect and optimism regarding the pregnancy outcome [54].

Implications for Nurses

In the era of easily accessible information from the internet, hospitalized pregnant women have different informational needs. These women expect the nurses to provide education information, mostly concerning the topic of how to prevent preterm labor. Implementing classes and diversional activities for high risk patients provides a unique opportunity for perinatal nurses to carry out supportive and educational roles in the hospital setting. Pregnant women seek more than factual information from providers. Health care professionals may not be aware of how anxious women are (Barber & Starkey, 2015). The information obtained from this study can assist caregivers in educating these women to decrease anxiety levels and improve fetal and maternal outcomes. Nurses need to spend more time assessing and educating hospitalized high-risk antepartum women according to their needs, as well as considering their social and spiritual needs as a topic of future research.

Conclusion

Implementing classes and activities for high risk patients provides a unique opportunity for perinatal nurses to carry out supportive and educational roles in the hospital setting. Hospitalized pregnant women have informational needs and seek more than factual information from healthcare providers. Not only is providing patient education important, but perhaps more critical to reducing patient anxiety is providing education on the topics they consider important. Identifying these topics begins with individual patient assessment, as this may vary considerably based on personal and situational characteristics

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflict of interest.

References

- Patel KP, Joshi HM, Patel VJ (2016) A study of morbidity and drug utilization pattern in indoor patients of high-risk pregnancy at tertiary care hospital. International Journal of Reproduction, Contraception, Obstetrics and Gynecology 2(3): 372-378.

- Lederman RP, Boyd E, Pitts K, Roberts Gray C, Hutchinson M, et al. (2013) Maternal development experiences of women hospitalized to prevent preterm birth. Sex Reprod Healthc 4(4): 133-138.

- Loyet M, McLean A, Graham K, Antoine C, Fossick K (2016) The fetal care team: Care for pregnant women carrying a fetus with a serious diagnosis. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 41(6): 349-355.

- Currie J, Barber C (2016) Pregnancy gone wrong: Women’s experiences of care in relation to coping with a medical complication in pregnancy. New Zealand College of Midwives Journal 52: 35-40.

- Kent RA, Yazbek M, Heyns T, Coetzee I (2015) The support needs of high-risk antenatal patients in prolonged hospitalisation. Midwifery 31(1): 164-169.

- Lee S, Ayers S, Holden D (2014) A metasynthesis of risk perception in women with high risk pregnancies. Midwifery 30(4): 403-411.

- Tan PC, Zaidi SN, Azmi N, Omar SZ, Khong SY (2014) Depression, anxiety, stress and hyperemesis gravidarum: temporal and case-controlled correlates. PloS one 9(3): e92036.

- Thiagayson P, Krishnaswamy G, Lim ML, Sung SC, Haley CL, et al. (2013) Depression and anxiety in Singaporean high-risk pregnancies-prevalence and screening. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 35(2): 112-116.

- McDonald SW, Kingston D, Bayrampour H, Dolan SM, Tough SC (2014) Cumulative psychosocial stress, coping resources, and preterm birth. Arch Womens Ment Health 17(6): 559-568.

- Shapiro GD, Fraser WD, Frasch MG, Séguin JR (2013) Psychosocial stress in pregnancy and preterm birth: associations and mechanisms. J Perinat Med 41(6): 631-645.

- Fan K, Siah K, Tan MN, Hasnah M, Chen Y, et al. (2014) Investigating knowledge gaps & level of anxiety of patient undergoing colonoscopy: a colonoscopy patient education questionnaire study. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 29: 1-5.

- Kalogianni A, Almpani P, Vastardis L, Baltopoulos G, Charitos C, et al. (2016) Can nurse-led preoperative education reduce anxiety and postoperative complications of patients undergoing cardiac surgery? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 15(6): 447-458.

- Garcia S (2014) The Effect of Patient Education on Anxiety Levels in Patients Receiving Chemotherapy for the First Time. Evidence-Based Practice Project Reports 1-47.

- Lee J, Hardesty LA, Kunzler NM, Rosenkrantz AB (2016) Direct interactive public education by breast radiologists about screening mammography: impact on anxiety and empowerment. J Am Coll Radiol 13(11): R89-R97.

- Abraham B, Sukumar S, Johnson A, Pothiyil DI (2016) Efficacy of educational program on anxiety of the patient undergoing magnetic resonance scan. International Journal of Pharma and Bio Sciences 7(2): B-107.

- Consonni EB, Calderon IM, Consonni M, De Conti MH, Prevedel TT, et al. (2010) A multidisciplinary program of preparation for childbirth and motherhood: maternal anxiety and perinatal outcomes. Reprod Health 7(1): 1-28.

- Vlemmix F, Warendorf JK, Rosman AN, Kok M, Mol BWJ, et al. (2013) Decision aids to improve informed decision‐making in pregnancy care: a systematic review. BJOG 120(3): 257-266.

- Attard J, Baldacchino DR, Camilleri L (2014) Nurses' and midwives' acquisition of competency in spiritual care: A focus on education. Nurse Educ Today 34(12): 1460-1466.

- Ingadottir B, Johansson Stark Å, Leino Kilpi H, Sigurdardottir AK, Valkeapää K, et al. (2014) The fulfilment of knowledge expectations during the perioperative period of patients undergoing knee arthroplasty–a Nordic perspective. J Clin Nurs 23(19-20): 2896-2908.

- Gupton A, Heaman M (1994) Learning needs of hospitalized women at risk for preterm birth. Appl Nurs Res 7(3): 118-124.

- Leino Kilpi H, Jaana V (1994) The patient's perspective on nursing quality: developing a framework for evaluation. Int J Qual Health Care 6(1): 85-95.

- Petersen JJ, Paulitsch MA, Guethlin C, Gensichen J, Jahn A (2009) A survey on worries of pregnant women-testing the German version of the Cambridge Worry Scale. BMC Public Health 9(1): 490.

- Spielberger C (1970) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (Self-evaluation questionnare). Consulting Psychogyists Press-Palo Alto, California, USA.

- Teichman Y, Malineck F (1978) Manual for the Hebrew state-trait anxiety inventory. Tel Aviv, Israel: Tel Aviv University, Israel.

- Leichtentritt RD, Blumenthal N, Elyassi A, Rotmensch S (2005) High-risk pregnancy and hospitalization: the women's voices. Health Soc Work 30(1): 39-47.

- Mettling K, Rubarth L (2012) Examining the relationship between antenatal education and stress levels of high-risk pregnant women on bed rest. [Thesis]. United States, Omaha: Creighton University, USA.

- Thompson D (2017) A framework to guide effective patient education. Primary Health Care 27(2).

- Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, Zeitz K (2013) What are the core elements of patient‐centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs 69(1): 4-15.

- Richter MS, Parkes C, Chaw Kant J (2007) Listening to the Voices of Hospitalized High‐Risk Antepartum Patient. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 36(4): 313-318.

- Curran L, McCoyd J, Munch S, Wilkenfeld B (2017) Practicing maternal virtues prematurely: The phenomenology of maternal identity in medically high-risk pregnancy. Health Care Women Int 38(8): 813-832.

- Höglund E, Dykes AK (2013) Living with uncertainty: A Swedish qualitative interview study of women at home on sick leave due to premature labour. Midwifery 29(5): 468-473.

- MacKinnon K (2006) Living with the threat of preterm labor: women’s work of keeping the baby in. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing 35(6): 700-708.

- Saigal S, Doyle LW (2008) An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet 371(9608): 261-269.

- Remennick L (2006). The quest for the perfect baby: why do Israeli women seek prenatal genetic testing? Sociol Health Illn 28(1): 21-53.

- Gaucher N, Nadeau S, Barbier A, Janvier A, Payot A (2016) Personalized Antenatal Consultations for Preterm Labor: Responding to Mothers' Expectations. J Pediatr 178: 130-134.

- Harrison MJ, Kushner KE, Benzies K, Rempel G, Kimak C (2003) Women's satisfaction with their involvement in health care decisions during a high‐risk pregnancy. Birth 30(2): 109-115.

- Souza NLd, Araújo ACPF, Azevedo GDd, Jerônimo SMB, Barbosa LdM, et al. (2007) Maternal perception of premature birth and the experience of pre-eclampsia pregnancy. Rev Saude Publica 41(5): 704-710.

- Faller H, Koch U, Brähler E, Härter M, Keller M, et al. (2016) Satisfaction with information and unmet information needs in men and women with cancer. J Cancer Surviv 10(1): 62-70.

- Grimes HA, Forster DA, Newton MS (2014) Sources of information used by women during pregnancy to meet their information needs. Midwifery 30(1): e26-e33.

- Kraschnewski JL, Chuang CH, Poole ES, Peyton T, Blubaugh I, Pauli J, et al. (2014) Paging “Dr. Google”: does technology fill the gap created by the prenatal care visit structure? Qualitative focus group study with pregnant women. J Med Internet Res 16(6): e147.

- Grant KA, McMahon C, Austin MP (2008) Maternal anxiety during the transition to parenthood: a prospective study. J Affect Disord 108(1): 101-111.

- Gourounti C, Karapanou V, Karpathiotaki N, Vaslamatzis G (2015) Anxiety and depression of high-risk pregnant women hospitalized in two public hospital settings in Greece. International Archives of Medicine 1-8.

- Gourounti C, Karpathiotaki N, Vaslamatzis G (2015) Psychosocial Stress in High Risk Pregnancy. International Archives of Medicine 1-8.

- Kartal YA, Oskay UY (2017) Anxiety, Depression and Coping with Stress Styles of Pregnant Women with Preterm Labor Risk. International Journal 10(2): 716.

- Denis A, Michaux P, Callahan S (2012) Factors implicated in moderating the risk for depression and anxiety in high risk pregnancy. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 30(2): 124-134.

- Barber CC, Starkey NJ (2015) Predictors of anxiety among pregnant New Zealand women hospitalised for complications and a community comparison group. Midwifery 31(9): 888-896.

- Lee S, Ayers S, Holden D (2012) Risk perception of women during high risk pregnancy: a systematic review. Health, risk & society 14(6): 511-531.

- Barlow JH, Hainsworth J, Thornton S (2008) Women's experiences of hospitalisation with hypertension during pregnancy: feeling a fraud. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 26(3): 157-167.

- Newham JJ, Westwood M, Aplin JD, Wittkowski A (2012) State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) scores during pregnancy following intervention with complementary therapies. J Affect Disord 142(1-3): 22-30.

- Rahimi F, Ahmadi M, Rosta F, Majd HA, Valiani M (2015) Effect of relaxation training on pregnancy anxiety in high risk women. Safety Promotion and Injury Prevention 2(3): 180-188.

- Moreno Peral P, Conejo Cerón S, Rubio Valera M, Fernández A, Navas Campaña D, et al. (2017) Effectiveness of psychological and/or educational interventions in the prevention of anxiety: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA Psychiatry 74(10): 1021-1029.

- Dijkstra H, Albada A, Cronauer CK, Ausems MG, van Dulmen S (2013) Nonverbal communication and conversational contribution in breast cancer genetic counseling: are counselors’ nonverbal communication and conversational contribution associated with counselees’ satisfaction, needs fulfillment and state anxiety in breast cancer genetic counseling? Patient Educ Couns 93(2): 216-223.

- Mann KS (2011) Education and health promotion for new patients with cancer: A quality improvement model. Clin J Oncol Nurs 15(1): 55-61.

- Byatt N, Hicks Courant K, Davidson A, Levesque R, Mick E, et al. (2014) Depression and anxiety among high-risk obstetric inpatients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 36(6): 644-649.

-

Ela Raizman. Fulfillment of Informational Needs and Anxiety in High-Risk Pregnant Women Hospitalized for Preterm Birth. Iris J of Nur & Car. 2(2): 2019. IJNC.MS.ID.000534.

-

Anxiety, High-Risk Pregnant, Preterm Birth, Informational Needs, Hospitalization, Health, Pregnancy Stress, Hospital Care, Oncology Patients, Psychiatric Disorder, Educational Program, Demographic, Bio Physiological, Neonatal, Maternal, Behavior Changes

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.