Research Article

Research Article

Beyond the Rural Pipeline Approach: Policy Considerations in the Making of a Rural Workforce

Nontsikelelo O Mapukata*

Division of Public Health Medicine, Health Sciences Campus, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Nontsikelelo O Mapukata, ntsiki.mapukata@uct.ac.za

Received Date: September 11, 2025; Published Date: September 18, 2025

Abstract

The enduring health workforce crisis, which has culminated in the maldistribution of healthcare professionals, particularly in rural South Africa, is considered a global challenge. This crisis was further exacerbated by the emergence of the novel coronavirus in 2019. In 2020, as part of a doctoral thesis, an examination was conducted into the influence of habitus in the professionalisation of twenty-one rural-origin final-year health sciences students studying at the University Cape Town to become doctors and health and rehabilitation therapists. Using an integrative methodology, the literature on pipeline strategy, which was presented two decades ago as a preferred approach for recruiting and retaining a rural health workforce, was reviewed. Furthermore, the relationship between policy and practice implementation was examined, along with an evaluation of universities’ contributions to meeting the health needs of South Africans. As an outcome of this policy review, solutions to address ongoing workforce challenges are presented. Participants’ lived experiences revealed that, despite having a generative habitus that had the capacity to transform, poor policy implementation and universities’ failure to meet transformation targets had implications for their practice. Thus, beyond the rural pipeline, a multimodal approach is proposed as an alternative to making a rural workforce.

Transdisciplinary contribution: The successful implementation of key priority areas could contribute to attaining universal health coverage in South Africa and beyond.

Keywords: health workforce; multimodal approach; pipeline approach; policy review; rural workforce

Background

The chronic shortage of healthcare workers in rural areas is well-documented. It is attributed to inadequate production, poor recruitment, inadequate retention, and staff mismanagement [1- 4]. The urban-rural dichotomy in the health workforce distribution was considered an obstacle in achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) [5]. In South Africa (SA), Mulaudzi and colleagues described the human resources for health (HRH) crisis as a challenge in the attainment of MDGS 4, 5, and 6 [6]. It remains an obstacle in the attainment of Sustainable Development Goals [7].

Due to the emergence of the novel coronavirus as a global pandemic in 2019, entrenched health inequalities were exacerbated, placing enormous burdens on frontline healthcare workers [8]. The pandemic threatened what was already regarded as a fragile health care system [9]. This compounded existing challenges as the WorldHealth Organization (WHO) predicted a global shortfall in HRH of 18 million workers by 2030. This will likely disrupt scheduled plans to achieve universal health coverage [10,11].

This shortage is even more pronounced in Africa, as only seventeen countries submitted a full strategy policy document that responds to HRH challenges according to Afriyie and colleagues [12]. In contrast to the challenges cited by Afriyie et al., the National Department of Health in SA has been actively publishing a five-year strategy document on HRH [13]. Yet, particular circumstances in all categories of healthcare workers have resulted in ongoing shortages and maldistribution of the workforce in rural areas [4,10]. As the thesis inquiry had identified gaps between policy implementation and outcomes [14], it was prudent to understand the relationship between policy and practice. Moreover, examining universities’ contribution and responsibility in meeting South Africans’ health care needs was just as critical. An integrative review and thematic analysis approach was used to understand the tensions in recruiting and retaining health professionals in rural SA.

The rural pipeline strategy as a global response

As an outcome of the gaps in policy referred to earlier, the World Health Organization recommended a complete overhaul of university admissions policies in 2010 to address the imbalances in the health workforce [15]. Consequently, national governments were required to prioritise drawing future generations of the health workforce from communities with an identified need. Based on scholarly evidence from local and international studies, the consensus among researchers is that equitable access to healthcare would be possible if the future workforce were drawn from rural communities [1,2,5,16]. This was premised on growing evidence that students of rural origin have a higher propensity to return to their communities to practice as healthcare professionals (HCPs), provided they are socialised in context [1,2,5,17-19].

Presented as a two-pronged approach [20], targeted recruitment is a well-established programme locally and internationally. It involves creating opportunities for students of rural origin to register for health sciences programmes [2,5,16-20]. This is achieved by providing rural exposure during undergraduate training through community site visits [1-3,5,19], rural electives [21], exposure to primary health care settings [1,3,16,17,19,22] as well as targeted training in rural practice at postgraduate level [23]. Funding is available as bonded scholarships or student loans that must be serviced upon graduation. In the early 2000s, two scholarship programmes were launched in SA — the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits) Initiative for Rural Health Education (WIRHE) and Umthombo Youth Development Foundation (UYDF). These two scholarships successfully recruited students from rural communities in the North West, Limpopo, Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal provinces. Supported exclusively by private funders at inception, students sign a year-on-year contract to provide service at the end of the study period. In return, students must return to facilities close to their communities at the end of the training period to provide health care [17,18]. Despite these initiatives, poor retention continues to be a challenge in rural communities. Additionally, the South African government introduced specific policy initiatives to address the maldistribution of the health workforce. These included a rural allowance [24,25,26], Occupational-Specific Dispensation (OSD) [27,28] and a year-long community service [24,29,30].

Rural allowance is a non-pensionable recruitment allowance ranging from 8-12% %. It is payable to healthcare workers based in rural nodes and underserved areas as defined by the Department of Public Works in South Africa. Within this category is a Scarce Skills allowance ranging from 10-15% paid to designated categories of healthcare professionals with specialised skills who work full time in rural areas. Examples include a psychiatrist or a professional nurse, a critical care nurse.

Occupational-specific dispensation provides differentiated remuneration dispensations across all sectors of the public sector health service. It caters to the unique needs of the different occupations and prescribes grading structures and job profiles to eliminate inter-provincial variations. It also provides adequate and clear salary progression and career-pathing opportunities.

Whilst these allowances were valued, they had limited success in retaining HCPs. Factors influencing their decision to stay or leave, besides professional development, included job satisfaction, relationships with colleagues, and safety and security [26,28]. In a paper reporting on rural allowances in KwaZulu-Natal, Mburu and George highlighted that apart from problems like water and electricity disruptions, unavailability of equipment and stock shortages, there were also conflicts between allopathic and Western medicine approaches. The patients’ health-seeking behaviour and cultural beliefs were considered to hinder effective healthcare delivery efforts [26].

On the other hand, the OSD allowance in Mpumalanga guaranteed staff retention only in rural facilities with academic affiliation. In non-affiliated rural facilities, staff complained about certain HCPs departing to find schools that would meet their children’s educational requirements [28]. As reported by Reid et al., a year-long community service program achieved its short-term goal, as access to healthcare improved each year that graduates were based in rural facilities [24]. Yet, despite positive encounters with their clients, as van Stormbroek and Buchanan reported, rehabilitation therapists placed in rural communities reported various challenges. Key amongst these were a lack of supervision and linguistic difficulties [29]. Thus, senior healthcare professionals who were established in their careers were most likely to commit to rural areas for extended periods. On the other hand, younger HCPs, particularly those self-funded or with no contractual obligations to funders, prioritised professional development and opportunities to specialise over short-term financial gains [24,30].

Overall challenges in implementing the rural allowances included policy ambiguity regarding the definition of rural areas and the categories of staff who qualified for the rural allowance [24-28]. Universities only presented limited exposure to health care facilities in rural communities, and at times this exposurewas only offered to students in their final year [22]. Although there is some improvement in other South African universities, at the University of Cape Town (UCT), rural exposure remains limited, similar to the findings reported in a study carried out at the University of the Witwatersrand [22]. Except for those who had received bonded scholarships or grown up in rural communities, many rehabilitation therapists were ill-prepared to provide care in rural areas beyond the obligatory period [29]. Based on the above, although universities had good intentions, these graduates did not perceive themselves as having a role in addressing the HRH crisis [14].

The maldistribution of a health workforce

Wary of the disparities between policy intentions and implementation hurdles, the researcher’s interest lay in grasping the impact on healthcare delivery in rural South Africa. Several articles were reviewed, specifically focusing on depicting the South African situation. Using data that was extracted from the Health Professions Council of South Africa’s database to forecast future demand for medical doctors in South Africa, Tiwari et al. [32], reported that the profession continued to be dominated by older white males and younger white females. Furthermore, there were concerns about the national shortage of the rehabilitation workforce in South Africa [11], as their distribution was primarily concentrated in three of South Africa’s nine provinces, further validating this issue. Practitioners preferred work placements in affluent cities in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and Western Cape provinces [33]. As a result of the inequitable allocation of rehabilitation therapists, many are based in the private sector servicing only 17 per cent of South Africa’s population [34]. Other contributing factors cited by Ned et al., were racial inequality (66 per cent white) and feminisation of the workforce (95 per cent females) [33]. Similarly, in a discrete choice experiment, medical students at UCT and the University of the Witwatersrand cited a preference for city living as this would increase access to academic hospitals and thus, opportunities to specialise [31,35]. This finding was consistent with earlier reports by Reid on the limited effectiveness of rural allowances [24].

Thus, as evidenced by the researcher’s earlier arguments, financial and non-financial incentives were inadequate in addressing ongoing challenges and in retaining a rural workforce. As higher education institutions (HEI) are tasked with the responsibility of enrolling students who come from communities where there is a shortage of HCPs, universities must integrate these students into the communities they will serve upon graduation. Considering the statements above, the mandate to actualise transformation targets (racial, gender, recruitment, and training) falls within the ambit of South Africa’s HEIs. Similarly, Ntuli and Maboya [28] argue for a parallel process focusing not only on increasing the number of HCPs, but also addressing push factors that have impeded the implementation of MDGs and pose similar threats to SGDs.

Why is this important in South Africa?

Equitable access to health care is a social justice issue [24] and is considered a constitutional mandate. Considering the problems cited previously (such as the limited efficacy of financial and nonfinancial incentives, graduates’ inclination towards urban living, and the difficulties HEIs face in achieving transformation targets), three guiding documents were scrutinised that outline strategies for the education and training of a future workforce. These documents include the two policies aimed at ensuring equitable access to universal health coverage. These are the “Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030” published by the World Health Organization [11] and the “2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy: Investing in the Health Workforce for Universal Health Coverage” published by the National Department of Health of the Republic of South Africa [13]. The third document focusing on training health professionals for the 21st Century, the recommendations offered by the “2010 Lancet Commission” were an outcome of structured deliberations by a team of global experts over a year to consider public health needs and health sciences education in an era of rapid globalisation [36]. The three documents highlight the HRH crisis, particularly in rural and remote areas. Thus, the skills imbalance and maldistribution of the workforce impacted health outcomes mostly in rural South Africa.

All three frameworks categorised interventions into four broad areas in response to the challenges referred to earlier. Three of the four interventions examined in this study were found to be relevant: inadequate production, insufficient recruitment, and low retention rates, all of which contribute as key factors driving efforts to scale up education and training for healthcare workers. Staff mismanagement was beyond the scope of the study. The analysis was informed by the main points within each of the three policy recommendations, which were presented as goals and objectives for each framework. The WHO “Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030” presents recommendations for low- and middle-income countries focusing on initiatives to improve access to primary health care and promote universal access to healthcare [11]. The National Department of Health’s “2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy” is committed to producing competent and caring multi-disciplinary healthcare workers, and it has called for teaching and training that is transformative, equitable, and socially accountable [13]. Lastly, the Lancet Commission recommended adopting a competency-based approach and enrolling students who are ‘fit for purpose’ [36], wherein students of rural origin can be capacitated to provide healthcare in rural areas. The other expectation is that graduates’ knowledge must be locally relevant, and they must be familiar with disease processes and the healthseeking behaviour of their patients. Their training must also consider the global perspective. For example, with the outbreak of COVID-19, teaching and training in South Africa’s universities were adjusted to facilitate a process whereby health sciences students gained knowledge about the virus. At UCT, a few students were sufficiently skilled to assist during the roll-out phase of the vaccine through their participation in contact tracing [37]. However, one of the prevailing challenges, as presented earlier, in South Africa and globally, is the absence of a uniform definition of rural and rurality, except that in SA these areas reflect the broader history of colonialism and dispossession [43]. Definitions are contextspecific or purpose-driven. In a forthcoming article, the researcher proposes new descriptors of rurality. Having considered the HRHchallenges and the absence of a uniform definition of rurality, the influence of habitus in the professionalisation of health sciences students (HSS) from rural SA was explored.

Lived experiences of rural-origin students and key findings

During the recruitment phase, the researcher established that records obtained from UCT’s Institutional Planning Division classified 13 % of the 2020 final-year class (n=369) as students from rural schools based on the last high school they attended as an indicator of rurality. The study revealed that 7% of the 2020 class were misclassified as they attended private and elite schools in the Quintile five band. These schools have the best resources and are geographically located in exclusive locations in rural SA. On the other hand, low-resourced schools in the Quintiles one to three band, are often based in rural and underserved areas lacking basic amenities in schools such as libraries, computers and books or have limited supplies and frequently have interrupted or no electricity and water [44]. As such, there was a small pool of true rural-origin students as these students are often underrepresented especially in historically white institutions such as UCT and Wits [43, 44]. Twenty-one final-year rural-origin HSS students studying to become doctors and health and rehabilitation therapists at UCT consented to participate in a qualitative study that employed indepth interviews and journal reflections to gather data about their lived experiences. Drawing from Bourdieu’s social constructivism theory, which was adopted as the conceptual framework, the broad study examined the interplay between socialisation, experience, and professional practice (Figure 1).

The habitus the researcher aimed to investigate comprised unconscious acts and dispositions performed routinely, encompassing both subjective and objective experiences influenced by context, as described by Bourdieu. The researcher was interested in exploring the influence of their rural habitus on their training and in evaluating the forms of capital that rural origin students had access to, as described in a 2020 paper [42].

Capital in this paper is dived into social capital (sum of resources that accrue to an individual or a group through networks.), symbolic capital (prestige and wards, status (mentors, committee members, council members and legitimate authority (cultural practice), cultural capital (institutionalized – matric certificate and awards and embodied forms – (accent, habits, tastes mannerisms, style and tastes) that serves as currency that helps navigate institutional culture and economic capital (assets such as computers and property that can be converted into cash).

Secondly, the researcher sought to understand the relationship between rural origin and rural education to consider the field’s influence and how this would impact the participants’ future practice [42].

The field includes the school and university as a space for generating cultural capital. Players in the field include teachers, lecturers, clinical educators, patients, and other students. Administrators are the agents who enforce rules.

In clinical spaces, participants experienced a series of shifts and transformation of their habitus and could identify mentors and role models. Some reported a second phase of constrictions in their habitus particularly in the academic hospital. They experienced incidents of racism and subsequent discrimination from patients who only cooperated when approached by another student of the same race. Similarly, in the same facility a few clinicians refused to teach them even when they were in a mixed group with other students. Drawing from a relational habitus, they gravitated towards African patients to moderate incidents of racism. Their social attributes (greeting and showing respect) translated into professional attributes. Study outcomes suggested a mutually beneficial relationship between rural origin and health sciences students’ sensitivity to the needs of their patients. This is, in addition to participants defining a role for district health platforms in facilitating multiprofessional learning. In spite of empirical evidence linking rural origin to rural practice, considering these findings and the earlier discussion of policy challenges, relying solely on the rural pipeline approach presents a linear view to what is a complex problem.

In the absence of a policy review, this understanding about the influence of habitus on professionalisation of rural-origin HSS and its value in graduating health professionals who prioritise a patient-centred approach, does not, on its own, generate a future workforce. The thesis offered insights about attributes of a primary habitus rooted in family and community and a transforming secondary habitus as this contributed to the generation of academic capital. This study identified inherent vulnerabilities as contributors to their disorientation to the university context. As participants were prone to mental health challenges in addition to navigating racism and discrimination, a shift in the recruitment approach of a future workforce is suggested [14].

What should policymakers do?

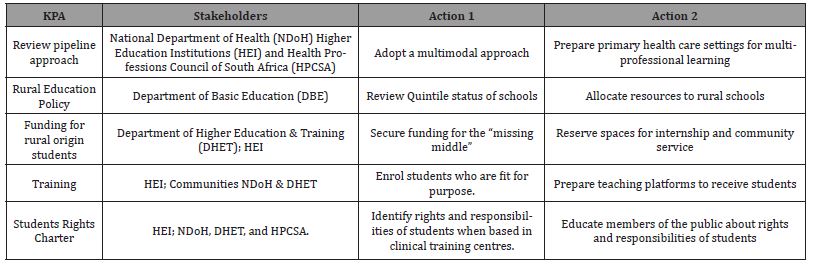

Considering the types of capital students of rural origin have access to (Table 1), this shift must prioritise them and incorporate a multi-modal approach to creating a rural workforce.

Some of the study participants who attended rural schools in the Quintile one to three band faced numerous challenges similar to those reported in papers that explored the university experiences of students from low-resource settings [43,44]. These experiences are congruent with findings documented in the Stats SA Report on the status of nodal areas in rural South Africa [39]. The nodal areas were notably poor, predominantly occupied by black African families and lacking basic resources. These limitations imposed endless burdens on the participants’ educational journey. As such, although some of the study participants were high achievers in school, they were illprepared for university. As stated earlier, 50% of the students classified as rural-origin students attended elite and private schools, which provided them with access to a wide range of resources. Consequently, this misclassification of schools extended undue privilege to students educated in elite and private schools (Quintile five). This was in contravention of the pipeline approach and had an impact on enrolment targets of students of rural origin. This in turn manifested as challenges in the retention of recently graduated health professionals [31,35]. Accordingly, the Rural Education policy as part of the amended National Education Policy Act No. 27 of 1996 [38], must be reviewed such that the classification of schools reflects the true Quintile status. Considering the domino effect as an outcome of poor implementation of the Rural Education policy, resources should be directed to schools based on their Quintile status to ensure that rural-origin students are adequately prepared for university [38].

Table 1: Key Priority Areas (KPAs): A multimodal approach.

Currently in South Africa, beyond community service, placement of rehabilitation therapists favours affluent cities in the three major provinces: Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal, and the Western Cape Province [30,33]. Given the above, universities should admit health sciences students whose profiles mirror the communities to which the graduates will be required to provide health care. Rural classification should extend beyond the school location to include indicators that evaluate students’ experiences in and out of school.

Secondly, universities should structure their curricula to ensure early exposure to rural health practice. Thirdly, the role of communities in facilitating training of health sciences students should be redefined in a mutually beneficial partnership to enable universal access to health care. Fourthly, there should be a shift in the training approach so that graduates are effective during their community service and are sensitised to the kinds of clients and patients they will interact with.

As such, primary health care centres as decentralised training platforms must be strengthened to meet the goals of multiprofessional learning. Congruent with the recommendations of the Lancet Commission [36], a competency-based approach should be the focus of all training so that graduates function as reflective practitioners and are considerate of their clients’ and patients’ socioeconomic status. Lastly, universities must address the feminisation and racial profile of health sciences students and plan for positive learning experiences in rural communities.

In strategic collaborations with faculties of health sciences, the National Department of Health (NDoH) should fund specific bonded scholarships for South African students of rural origin whose family income is above the threshold of R350 000 per annum and falls into the category known as the ‘missing middle. Cloete describes the missing middle as a “group of students who do not qualify for the National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) funding and at the lower middle-class end, cannot easily access bank loans” as they often do not have the required security to guarantee a loan [40, p.127]. Such students must be socialised to practice in their communities throughout the study period by facilitating structured placement that accrues curriculum credits. The NDoH should, in turn, ensure that students funded through bonded scholarships have secure internship placements. Additionally, such graduates must be supported in their plans to pursue postgraduate training, provided they demonstrate a commitment to return to their communities to provide health care.

As indicated by the study findings, where some participants were not taught during clinical rotations, considering the vulnerability of rural-origin HSS to mental health challenges and discriminatory practices, UCT should prepare academic hospitals and affiliated platforms to receive such students. In closing gaps in providing a just and fair approach in training a future workforce, lessons can be drawn from the National Patients’ Rights Charter [41]. This Charter outlines the standard of healthcare that patients have access to, including their rights and responsibilities when they present at public health facilities throughout South Africa. In this regard, universities should come together to develop a National Students’ Rights Charter. This should inform the rights and responsibilities of health sciences students when they are based in clinical training centres.

Conclusions

The policy considerations presented in this paper should inform policymakers and educators in developing a fair and just approach to training the future rural workforce. The successful implementation of the key priority areas outlined in Table 1 is expected to contribute to achieving universal health coverage in South Africa and beyond.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HRECM180308) at the University of the Witwatersrand, where this research was conceptualised, and by the HREC at the University of Cape Town (Ref 619/2019), where the study was located. All 21 participants submitted written consent to participate in the research and publication of findings.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the study participants and the promoters. This article is drawn from findings in a thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Public Health at the University of the Witwatersrand entitled ‘Making a rural workforce: exploring the habitus of health sciences students from rural South Africa’ and supervised by Professors Manderson and Reid.

URL: https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/34355

Competing Interests

The author declares they have no financial or personal relationships that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ contributions

Sole author.

Funding information

The study was funded through an institutional grant – the Emerging Researcher Grant.

Data Availability

Data sharing does not apply to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated agency of the author and the publisher.

References

- Wilson NW, Couper ID, De Vries E, Reid S, Fish T, et al. (2009) A critical review of interventions to redress the inequitable distribution of healthcare professionals to rural and remote areas. Rural and Remote Health 9(2): 1-21.

- Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Wortman JR (2008) Medical school programs to increase the rural physician supply: A systematic review and projected impact of widespread replication. Academic Medicine 83(3): 235-243.

- Tumbo JM, Couper ID, Hugo JF (2009) Rural origin health science students in South African universities. South African Medical Journal 99(1): 54-56.

- Malema RN, Muthelo L (2018) Literature review: Strategies for recruitment and retention of skilled healthcare workers in remote rural areas. EQUINET (Harare) and University of Limpopo (South Africa) Report (115).

- Strasser R, Neusy AJ (2010) Context counts: training health workers in and for rural and remote areas. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 88: 777-782.

- Mulaudzi FM, Phiri SS, Peu DM, Mataboge ML, Ngunyulu NR, et al. (2016) Challenges experienced by South Africa in attaining Millennium Development Goals 4, 5 and 6. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine 8(2): 1-7.

- World Health Organization & World Bank (2017) Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report. World Health Organization.

- Scheerens C, De Maeseneer J, Haeusermann T, Santric Milicevic M (2020) Brief commentary: why we need more equitable human resources for health to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Public Health 8: 573742.

- Hofman K, Madhi S (2020) The unanticipated costs of COVID-19 to South Africa’s quadruple disease burden. South African Medical Journal 110(8): 698-699.

- Shisana O, Dhai A, Rensburg R, Wolvaardt G, Dudley L, et al. (2019) Achieving high-quality and accountable universal health coverage in South Africa: a synopsis of the Lancet National Commission Report. South African Health Review 2019(1): 69-80.

- World Health Organization (2020) The African regional framework for the implementation of the global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030, 2020. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Africa.

- Afriyie DO, Nyoni J, Ahmat A (2019) The state of strategic plans for the health workforce in Africa. BMJ global health 4 (Suppl 9): e001115.

- National Department of Health, South Africa (2020) 2030 Human Resources for Health Strategy: Investing in the Health Workforce for Universal Health Coverage. Pretoria: Government printers, 2020 [Google Scholar].

- Mapukata NO. Making a rural workforce: exploring the habitus of health sciences students from rural South Africa (Doctoral dissertation), July 2022. University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- World Health Organization (2010) Increasing access to health workers in remote and rural areas through improved retention. Global policy recommendations. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- De Vries E, Reid S (2003) Do South African medical students of rural origin return to rural practice? South African Medical Journal 93(10): 789–793.

- Ross A, MacGregor G, Campbell L (2015) Review of the Umthombo youth Development Foundation scholarship scheme, 1999-2013. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine 7(1): 1-6.

- Mapukata NO, Couper I, Smith J (2017) The value of the WIRHE Scholarship Programme in training health care professionals for rural areas: Views of participants. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 9(1): 1-6.

- Woolley T, Sen Gupta T, Murray R (2016) James Cook University's decentralised medical training model: an important part of the rural workforce pipeline in northern Australia. Rural and Remote Health 16(1): 1-11.

- Carson DB, Schoo A, Berggren P (2015) The ‘rural pipeline’ and retention of rural health care professionals in Europe's northern peripheries. Health Policy 119(12): 1550-1556.

- Couper I (2015) Student perspectives on the value of rural electives. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine 7(1): 1-8.

- Nyangairi B, Couper ID, Sondzaba NO. Exposure to primary healthcare for medical students: experiences of final-year medical students. South African Family Practice. Google Scholar 52(5): 467-470.

- Strasser R (2016) Learning in context: education for remote rural health care. Rural and Remote Health 16(2): 1-6.

- Reid S (2004) Monitoring the effect of the new rural allowance for health professionals [Research project report]. Durban: Health Systems Trust, Google Scholar

- Ditlopo P, Blaauw D, Bidwell P, Thomas S (2011) Analysing the implementation of the rural allowance in hospitals in North West Province, South Africa. Journal of Public Health Policy 32: S80-93.

- Mburu G, George G (2017) Determining the efficacy of national strategies aimed at addressing the challenges facing health personnel working in rural areas in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine (1): 1-8.

- Ditlopo P, Blaauw D, Rispel L, Thomas S, Bidwell P (2013) Policy implementation and financial incentives for nurses in South Africa: a case study on the occupation-specific dispensation. Global health action 6(1): 19289.

- Ntuli ST, Maboya E (2017) Geographical distribution and profile of medical doctors in public Care and Family Medicine (1): 1-5.

- Van Stormbroek K, Buchanan H (2016) Community Service Occupational Therapists: thriving or just surviving? South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 46(3): 63-72.

- Reid SJ, Peacocke J, Kornik S, Wolvaardt G (2018) Compulsory community service for doctors in South Africa: A 15-year review. South African Medical Journal 108(9).

- George A, Blaauw D, Thompson J, Green-Thompson L (2019) Doctor retention and distribution in post-apartheid South Africa: tracking medical graduates (2007–2011) from one university. Human Resources for Health 17: 1-9.

- Tiwari R, Wildschut-February A, Nkonki L, English R, Karangwa I, et al. (2021) Reflecting on the current scenario and forecasting the future demand for medical doctors in South Africa up to 2030: towards equal representation of women. Human Resources for Health 19(1): 1-2.

- Ned L, Tiwari R, Buchanan H, Van Niekerk L, Sherry K, et al. (2020) Changing demographic trends among South African occupational therapists: 2002 to 2018. Human resources for health 18(1): 1-2.

- Rensburg R (2021) Healthcare in South Africa: How inequity is contributing to inefficiency. The Conversation.

- Jose M, Obse A, Zuidgeest M, Alaba O (2023) Assessing Medical Students’ Preferences for Rural Internships Using a Discrete Choice Experiment: A Case Study of Medical Students in a Public University in the Western Cape. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(20): 6913.

- Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, Cohen J, Crisp N, et al. (2010) Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. The Lance 376(9756): 1923-1958.

- Zweigenthal V, Perez G, Wolmarans K, Olckers L (2023) Health Sciences students’ experience of COVID-19 case management and contact tracing in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Medical Education 23(1): 1-9.

- Department of Basic Education (DBE) (2020) Government Gazette No. 41399 dated 26 January 2018: Rural Education Draft Policy, September 2017. Pretoria: Government Printing Works.

- Stats SA 2016. Monitoring Rural Development. South Africa Statistics.

- Cloete N (2015) The flawed ideology of “free higher education”. University World News 389(6).

- Health Professions Council of South Africa (2016) HPCSA guidelines for good practice in the health care profession. National Patients’ Rights Charter. Booklet 3. 1:1-8.

- Mapukata N (2020) Embodiment of particular ways of being: Habitus as an autobiographical narrative. Ubuntu: Journal of Conflict and Social Transformation 9(1): 9-24.

- Walker M, Mathebula M (2020) Low-income rural youth migrating to urban universities in South Africa: opportunities and inequalities. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 50(8): 1193-1209.

- Khupe C, Mapukata N (2024) University as border crossing: Exploring the experiences of health sciences students from low-resourced school communities. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South 8(3): 1-24.

-

Nontsikelelo O Mapukata*. Beyond the Rural Pipeline Approach: Policy Considerations in the Making of a Rural Workforce. Iris J of Nur & Car. 5(4): 2025. IJNC.MS.ID.000619.

-

Health workforce, Multimodal approach, Pipeline approach, Policy review, Rural workforce

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.