Mini Review

Mini Review

Assessing Patient Fall Risk on Psychiatric Units: A Comparison of Three Fall Risk Scales

Marshall B*, Giuliani DA, Kolodziej J, O Hagan G and Pradhanang L

Department of Nursing, William Paterson University, USA

Marshall B, Department of Nursing, William Paterson University, New Jersey, USA.

Received Date: February 12, 2020; Published Date: February 21, 2020

Introduction

Background: Patient falls in a hospital setting are considered serious, never events and vary according to unit specialty [1]. Around 2% of in patients will fall during their hospital stay [2], reflecting a number of different reasons and risks [3]. The National Database of Nursing Quality Indicators (NDNQI) collects data on multiple nursing events from over 2000 hospitals, categorizing specific nursing quality events for benchmarking (Press Ganey, nd) [4]. This allows for evaluation of nursing and hospital performance on events and issues of importance to patient safely and care. More often than not (76.6%) patients who fell were assessed for risk of falling [1]. Assessment of the sensitivity of the falls risk assessment tools, as well as their specificity for the type of clinical unit is important [3].

Psychiatric specific challenges: Intentional fall events, or those instances where a patient descends to the floor on purpose, are seen more frequently in psychiatric units than medical units [5]. NDNQI defined intentional fall events in an expansion of a review of defining falls, actually excluding intentional fall events out of the fall’s category of reporting. The amount of research that has occurred regarding inpatient safety on psychiatric units is limited, despite the fact that 26% of Americans have a diagnosable mental illness [6]. Sometimes, in a psychiatric unit, physical areas can be identified as increased risk factors. Five areas were defined using risk levels from 1-5, with 5 being the highest risk area. These areas were 5b) seclusion areas with patients who are experiencing aggressive behaviors, 5a) admitting areas where patients are not yet aware of the rules and boundaries and are new to interactions with staff, 4) Patients bedrooms and bathrooms, 3) activity rooms and group lounge rooms (IE TV rooms), 2) corridors and other areas where patients are easily being observed by staff, and 1) nurses stations and other staff only areas [7]. Hunt and Sine (2009) identified the architectural design as a factor in understanding patient and staff safety issues, supporting the need for designing psychiatric units with patient and staff safety in mind. The three factors identified by Hunt and Sine (2009) for falls in psychiatric units are flooring material, presence of grab bars and adequate lighting in halls and bedrooms. The study conducted by Hunt and Sine evaluated falls, among 6 other elements, over a 7-year period. Their study identified level four as having the most number of falls (390) and level 3 also at high risk (135). The total number of falls reported on the unit made up for 44% (n=582) of the seven larger categories of safety issues.

Wong and Pang assessed two fall risk assessment tools, The Morse Falls Scale (MFS)and The Wilson Sims Fall Risk Assessment Tool (WSFRAT), with psychogeriatric in patients. The pilot program was a part of the development of a fall’s prevention program. Their program identified time of day (nights), toileting, advanced age, dementia and gender (female) as increasing the risk factor for falls. Their conclusion was that the WSFRAT was a better indicator of risk for falls in their psychiatric units [8].

The current study examines and compares three fall risk assessment tools, The Morse Falls Scale (MFS) The Wilson Sims Fall Risk Assessment Tool (WSFRAT) and the Edmonson Psychiatric Falls Risk Assessment tool (EPFRAT) on an inpatient psychiatric unit. The aim of this study was to determine which assessment tool best identified risk for falling and provided nursing with information for patient fall prevention and management.

Method

Design: Randomized, comparative archived chart review.

Sample: The sample of charts were randomly drawn from hospital ID numbers of previous in-patients from the psychiatric ward. Three nurse researchers each randomly retrieved five archived charts.

Setting: A psychiatric dedicated, in-patient unit in a suburban medical center in New Jersey.

Procedure: Three nursing researchers were trained in chart review to identify the criteria for each of the fall’s assessment tools. Patient account numbers representing patients who had been discharged in the preceding year were randomly chosen. Each nurse evaluated five to seven charts. This provided a double-blind method concealing the identity of the patients. All charts were independently reviewed using each of the criteria from the three tools.

Each chart was reviewed to identify the variables established and measured by each of the three measurement tools. The criteria were cross listed to determine where the assessment tools shared criteria and where they differed. The final scores were compared across the three tools to identify where there was agreement between the surveys, with a focus on identifying those at highest risk for falls. Risk factors were tallied according to the scales and compared for consistency in results indicating level of patient fall risk. Total scores were compared across each patient. Twenty-four variables were identified across the three scales with an additional two variables identified by nurses for inclusion in any future scale.

Results

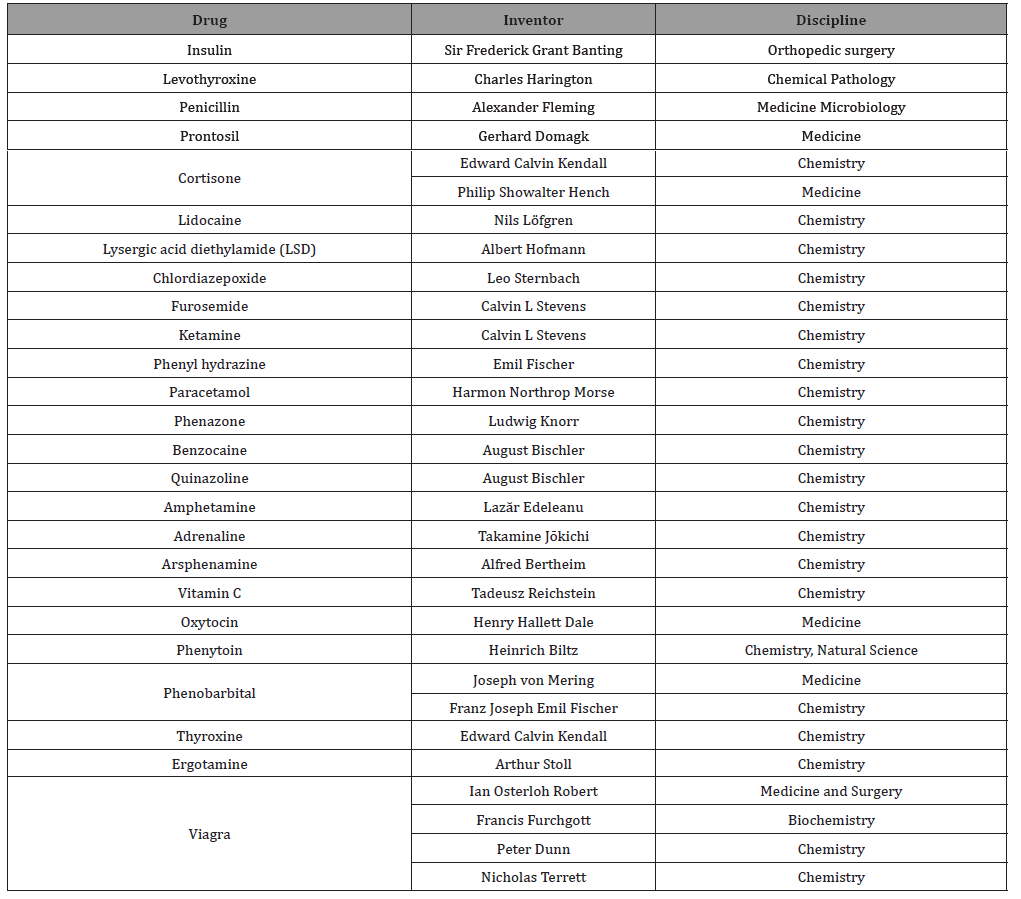

The final number of charts reviewed were 14. One chart was removed as the evaluation sheet was incorrectly completed on two scales. Scales were compared to see what variables were included in each of the scales. Twenty-four variables were identified between the three scales: Age, gender, mental status, cognition, physical status, elimination, impairments, gait/balance, history of falls, diagnosis, secondary diagnosis, ambulatory aids, IV therapy, nutrition, sleep disturbances, medication (general), mood stabilizers, benzo, diuretics, narcotics, sedative hypnotic, atypical antipsychotic, detox protocol and an area for clinical nursing judgment. . Table one reflects how age and gender are recorded on the three scales and the percentage of patients whose score identified those patients at risk for falls secondary to age or gender. Age as a fall risk was only considered in the Wilson Sims (WSFRAT) and Edmonson Scales (EPFRAT) scales, and gender only on the Wilson Sims (Table 1).

Table 1:Comparing three scales on Age and Gender as falls risk.

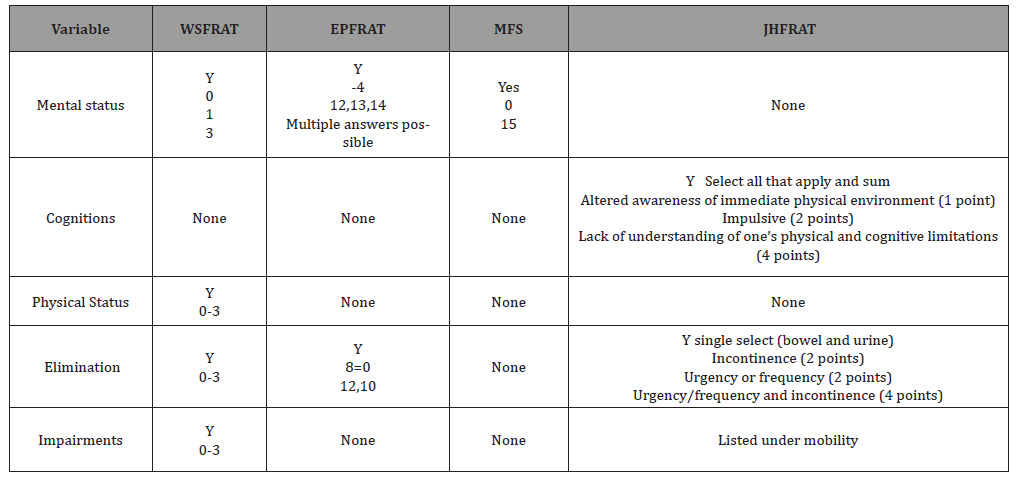

Mental status, elimination patterns, impairments and gait/balance variables were evaluated across the three scales

Table 2:Comparing four scales on Mental/physical status and mobility issues.

The WSFRAT lists three-point categories for mental status, 0 for oriented and cooperative, 1 for oriented and uncooperative, and 2 confused, memory loss, forgets limitations, intoxicated. Four-point categories exist on the Edmonson Scale, ranging from -4 for fully alert/oriented at all times, 13 agitation/anxiety, 13, intermittently confused, 14 confusion/disorientation. The Morse Scale provides two-point options, 0 for oriented to own ability, and 15 for forgets limitations. Elimination was identified in the WSFRAT and the Edmonson only (Table 2).

The scales were compared on the variables of: History of falls, Diagnosis, secondary diagnosis and ambulatory aids. History of falls and Ambulation/Gait/Balance/Mobility were identified in all four scales. History of falls differed between scales based on time sensitivity-immediate or within 3 months on the MFS and EPFRAT and within six months on the WSFRAT and JHFRAT. Diagnosis, Nutritional status, and sleep disturbances were only identified on the Edmonson scale, Secondary diagnosis, ambulatory aids and IV therapy were only identified on the Morse scale. The final score on all of the fall scales is tallied by the nurse, adding up the different points from the multiple variables.

Results the total scores from the three scales were in agreement related to falls risk approximately 80% of the time, (n=11) with the remaining 20% (n=3) reflecting differences in the level of risk (high and very high), not the disparity between risk or no risk. Correlations between the three falls scales were obtained. All three were significantly, highly correlated with each other. Wilson Sims correlated at a .907, p.000 with Edmonson and .930, p .000 with Morse, Edmonson and Morse correlated at .905, p.000 indicating the high level of relationships between all three scales.

Discussion

The randomized chart review reflected patients from an acute, voluntary in-patient unit. The high correlation of the three scales with this patient population demonstrates the strength of all three scales to identify patient falls risk in a psychiatric population. A number of major differences were identified between these three scales. Only the WSFRAT scale includes a place for nursing judgement to be recorded. The three scales differ greatly in the number of questions that need to be answered which reflected the amount of time the nurse would need to correctly fill out the scale.

Missing variables related to psychiatric falls, identified by nursing staff during the review, included 1) withdrawal risk, 2) medication change in last 48 hours , 3) suicide risk, and 4) constant Observation 1:1. Three major barriers and work arounds identified by nursing staff included additional time required to fill out the forms, lack of uniform use by all nursing staff, and the belief that the forms were not considered important by the medical staff or hospital administration. An administrative concern identified the lack of verification of proper use and communication of the results of the scale. Additionally, adequate training in the proper completion of the scale and handoff report was voiced.

Psychiatric in-patient units focus their specialized care on patients living with multiple mental health disorders. Unlike other specialty units, most of the patients are ambulatory, encouraged to socialize and required to attend meetings and mealtimes out of their rooms. Many patients have co-occurring medical problems, are prescribed polypharmacy, and may experience distortions in any their five senses all factors that exacerbate fall risk [9] identified multiple root causes of falls in psychiatric units using the Veterans Health Administration National Center for Patient Safety database that included patient mobility, use of bathroom and behavior related activities as the top patient risk factors for falls. Poor communication (8.9%) was identified as a non-patient risk for falls, and need for better falls assessment tools (8.9), increased staff education (19.9%) and developing better falls documentation tools (17.2%) were identified as remedial steps [9]. Seventy percent of falls with sustained injury on a psychiatric floor, identified by Lee et al., involved problems with policies, rules and procedures (almost 30% of the time), environmental/equipment hazards (24.6%) and communication (19.6%). Staff fatigue/scheduling problems, staff training, and characteristics of the facility made up another 18%, leaving only 8.9% of falls originating with patient characteristics.

Conclusion

This study indicated that the three scales were all reliable to each other in identifying patients risks for falls on an inpatient psychiatric unit. Risk identification can be accurately determined by any number of fall-risk tools. Identifying the risk for fall from patient characteristics is only one component of a multi-factorial organization problem. Patients risk can be determining as low moderate or high, but even the lowest risk patient can fall when staff fatigue, incorrect assessment or environmental hazards are present. Interventions for patient determined risk factors are utilized on patients who fall in the high-risk category. In order to address the organizational factors interventions, need to also be focused on the organizational tiers of responsibility from the staff to the development and implementation of policies and procedures. As indicated in the study by Lee et al (2012), 90% of the fall risk is grounded in physical, administrative and educational jurisdictions. By focusing our attention only on the 10% risk presented by a patient’s characteristics, the greater arena that is under the control of nursing and administration can be neglected. The nurses in this study expressed their concerns related to work arounds and barriers to proper implementation of the scales, which may present a larger hazard to patient safety than previously studied. Future studies might focus on the relative reduction of risk when environment, policy and procedures, and nursing education/ communication are the variables.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Bouldin EL, Andresen EM, Dunton NE, Simon M, Waters TM, et al. (2013) Falls among adult patients hospitalized in the United States: prevalece and trends. J Patient Saf 9(1): 13-17.

- Yauk S, Hopkins BA, Phillips CD, Terrell S, Bennion J, et al. (2005) Predicting in-hospital falls. Development of the Scott and White Falls Risk Screener. J Nurs Care Qual 20: 128-133.

- Chapman J, Banchand D, Hyrkas R (2011) Testing the sensitivity, specificity and feasibility of four falls risk assessment tools in a clinical setting. J Nurs Manag 19: 133-142.

- Press Ganey (nd). Improving Care Quality, prevent adverse events with deep nursing quality. South Bend, Indiana, USA.

- Staggs V, Davidson J, Dunton N, Crosser B (2015) Challenges in Defining and Categorizing Falls on Diverse Unit Types. J Nurs Care Qual 30(2): 106-112.

- Bayramzadeh S (2017) An Assessment of Levels of Safety in Psychiatric Units. HERD 10(2): 66-80.

- Hunt J, Sine D (2009) Common mistakes in designing psychiatric hospitals. AIA Academy Journal.

- Wong M, Pang P (2019) Factors associated with falls in psychogeriatric inpatients and comparison of two fall risk assessment tools. East Asian Arch Psychiatry 29(1): 10-14.

- Lee A, Mills PD, Watts BV (2012) Using root cause analysis to reduce falls with injury in the psychiatric unit. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 34(3): 304-311.

-

Marshall B, Giuliani D, Kolodziej J, O Hagan G, Pradhanang L. Assessing Patient Fall Risk on Psychiatric Units: A Comparison of Three Fall Risk Scales. Iris J of Nur & Car. 2(4): 2020. IJNC.MS.ID.000545.

-

Patient, Psychiatric, Risk Scales, Risk Assessment Tools, Medical Units, Diagnosable Mental Illness, Physical Areas, Nurses, Diuretics, Narcotics, Sedative Hypnotic, Atypical Antipsychotic, Detox Protocol, Clinical Nursing Judgment, Psychiatric Population

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.