Research Article

Research Article

The Impact of Mothers’ Knowledge and Attitudes on Malnutrition Prevention Practices Among Children Under Five in Thulamela Municipality, South Africa

Ratshibvumo A Annah1, Luhalima T Rhoda2* and Tshitangano T Grace3

1Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Public Health University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa

2University of Venda, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Advanced Nursing Sciences, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa

3University of Venda, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Public Health University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa

Luhalima T Rhoda, University of Venda, Faculty of Health Sciences, Department of Advanced Nursing Sciences, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, South Africa.

Received Date:January 02, 2023; Published Date:January 20, 2023

Abstract

Malnutrition is a global public health problem affecting most countries. Mothers’ knowledge and attitudes on malnutrition prevention practices are significant in tackling children’s malnutrition. The study investigated mothers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices of malnutrition preventive measures in children under the age of five in the Thulamela Municipality of South Africa. A quantitative approach was used, stratified sampling was adopted to sample clinics, and convenient sampling was used to sample 329 respondents. A self-administered questionnaire was used for data collection. SPSS version 25.0 was used for data analysis. Multiple regression was used to assess how knowledge and attitudes affected the prevention of malnutrition measures. The study findings indicated that 261 (92%) participants were knowledgeable about malnutrition preventive measures. The findings further revealed that respondents had positive opinions regarding feeding their children. The study recommends taking advantage of social media through awareness campaigns about childhood malnutrition and those communities be provided with health education regarding the importance of breastfeeding to promote a healthy lifestyle.

Keywords:Attitude; Children; Impact; Knowledge; Malnutrition prevention; Mothers; Thulamela Municipality

Introduction

Malnutrition is a public health problem affecting predominantly developing countries [1]. The World Food Program (WFP) defines malnutrition as “a state when a physical function of a person is impaired to the extent that it can no longer maintain sufficient bodily performance processes such as growth, pregnancy, lactation, resisting and recovering from an ailment”[2]. Child malnutrition in particular, is a major epidemiological problem in developing countries especially in Africa [3]. Countries are off-track to meet five out of six global maternal, infant, and young children nutrition (MIYCN) targets, on stunting, wasting, low birth weight, anaemia and childhood overweight [4]. In 2021 alone, there were about 149.2 million children under the age of 5 years who were stunted globally, 45.2 million were wasted and 38.9 million were overweight [4]. These challenges expose children to the risks of non-communicable diseases that can be prevented through breastfeeding.

The study conducted by Vember and Loots [5] in South Africa showed that millions of children in Africa are affected by malnutrition, particularly those under five-years-old. Malnutrition can be influenced by a lack of micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals [6]. This condition is common in poor communities and households of low educational status. In Africa, an estimated 56.6 million children are shorter for their age or are suffering from chronic undernutrition [7]. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, 41% of children under the age of five are malnourished. In South Africa, 3 out of 10 children are stunted [8]. Stunting is the most common anthropometric result of malnutrition that has a negative impact on children’s health. Stunting is being too short for one’s age because of long-term undernutrition. According to Dukhi [9] stunting was estimated to be 27% among South African children; whereas in 2018 alone, the proportion of stunted, underweight, and wasted children aged between 1 and 5 years in Gauteng Province was 17%, 6%, and 3%, respectively. The proportions of stunted, underweight, and wasting among 1–5-year-old children in the province of Limpopo were 24%, 12%, and 4%, respectively [9]. In addition, a higher proportion of 1–5-year-old children in the Limpopo Province had iron (14%) and vitamin A (76%) deficiencies compared to Gauteng, where the percentages were (65%) and 10%, respectively. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) [7], South Africa has a higher prevalence of stunting compared to Gabon, Libya and Egypt, and a lower prevalence of stunting compared to Botswana. Stunting is associated with poor brain development, which affects a child’s cognitive development, educational attainment, and productivity in adulthood which in turn affects the development potential of a nation [7]. Being malnourished in early childhood elevates the risks of infant and child morbidity and mortality and increases healthcare costs and social safety net expenditures [7].

According to Senekal, et al. [10], determinants of stunting are multi-factorial and mainly associated with households’ low socio-economic status and food insecurity, feeding practices, repeated infectious episodes in infants, and maternal health before, during, and after pregnancy. Nutrition-sensitive early childhood development and hygiene promotion are amongst the nutritionsensitive interventions suggested by UNICEF [7]. However, these interventions can be best implemented by people who are looking after children. Thus, women’s empowerment in terms of knowledge and attitudes regarding these malnutrition preventive interventions determines practice.

A review conducted by Adinma, et al. [1] indicated that poor breastfeeding habits where only 37% of children are exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life lead to waste in Nigeria. The review further revealed that anaemia is a serious side effect of nutrition deficiency during pregnancy [1]. In Bangladesh, a study was conducted to examine the extent of malnutrition among children between 0-59 months and it was found that malnutrition is the major cause of disease burden in developing countries [11]. Furthermore, an estimated 70% of malnourished children live in Asia [11]. This is a serious concern that should be addressed through a multidisciplinary approach.

Malnutrition causes long-term damage to the physical and mental development of children [12]. In 2012, the United Nations Children’s Fund recorded 9.2 million deaths of children under the age of five [7] because of malnutrition. About 200 million children globally fail to reach their potential in cognitive development because of poverty, poor health, and nutrition [13]. Millions of children in South Africa are affected by malnutrition and mortality and morbidity from poor diets is a major concern. A study by Loots et al [15] examined key factors associated with malnutrition among children aged between six months and five years in a semirural area of the Western Cape, South Africa [14] and emphasized the fundamental role of breastfeeding in the mental and physical development of children. It is imperative to make informed decisions about issues affecting children’s health to prevent deaths caused by malnutrition. This study investigated the impact of mothers’ knowledge and attitudes towards the suggested interventions on malnutrition prevention practices of mothers of children under five in the Thulamela Municipality, South Africa.

Methodology

Study design

The study adopted a cross-sectional descriptive design. A quantitative approach was used to investigate mothers’ knowledge, attitudes and practice of malnutrition preventive measures among children under the age of five in the Thulamela Municipality of South Africa.

Study setting

The study was conducted in Sibasa which is in Thulamela Local Municipality of the Limpopo Province. The area was purposively selected because it has a high record of malnutrition cases compared to other areas. All 07 clinics and 01 community health center located in Sibasa were included in the study. The area comprises about 700 000 Venda-speaking people and a few Tsonga-speaking individuals who are also fluent in Tshivenda [16].

Study population

The target population for this study was all mothers of children under five years, who were attending child immunization services in clinics in the Sibasa Local Area (Table 1).

Source: Department of Health, (2018).

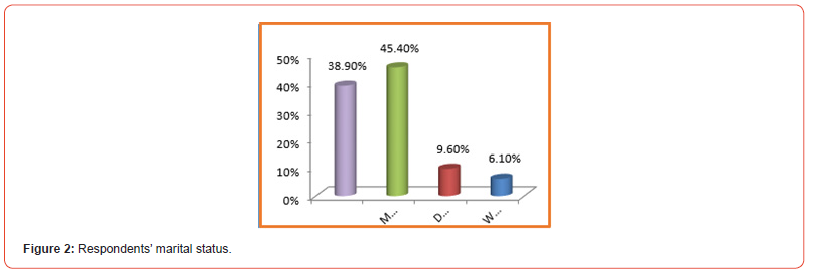

Calculation of sample of sample size and sampling

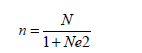

The sample size was calculated using the Slovin (1960) formula as cited by Manohar, et al. [17].

n=sample size of adjusted population

N=population size

e=accepted level of error usually set at 0.05

(Table 2) The total study sample size was calculated using Slovin’s formula above. The population size which makes the sum of 1876 was added with value 1 and multiplied by the level of error 0. 052. Therefore, the population size which is a denominator was divided by the numerator obtained after adding population size with the value of 1 multiplied by 0.052.

Data collection and tools

The data collection instrument was developed by the researcher based on nutrition literature and it was categorized into four sections namely section A (multiple choice) - demographic data, section B (multiple choice) - knowledge of malnutrition prevention, Section C (Likert scale)- attitude towards malnutrition preventive measures and Section D (multiple choice) – Malnutrition preventive practices. The instrument was pre-tested among mothers under five years visiting Thohoyandou health center, to check for clarity of questions, the time needed to complete the questionnaire and completeness of concepts. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into Tshivenda, Xitsonga, and Sepedi languages.

Data analysis

The SPSS version 25.0 was used for data analyses and results are presented in bar charts, graphs, and frequency tables. Since the study data was ordinal, a multiple regression test was performed to determine the impact of knowledge and attitudes on mothers’ malnutrition preventative practices. The level of significance was set at P=0.05, with any value above 0.05 regarded as significant (no association).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was sought and obtained from the University of Venda’s Higher Degrees and Ethics Committee (Registration number: SHS/19/PH/08/1604). Permission was obtained from the Limpopo Provincial Department of Health to use the clinics for meeting mothers of children under five years and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Result

Respondents’ demographic information

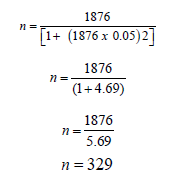

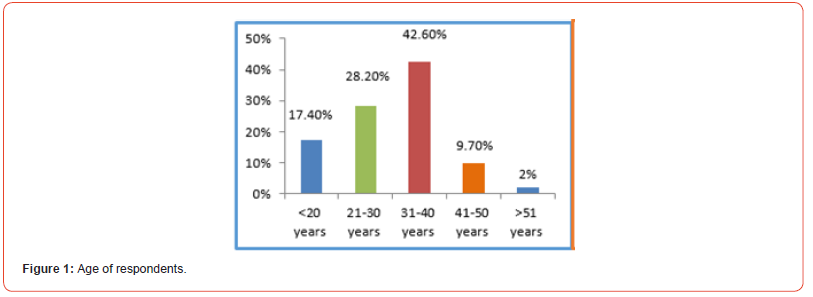

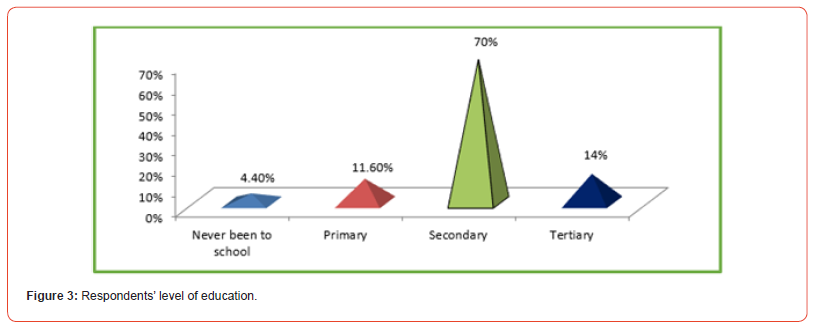

A total of 329 mothers participated in the study with a response rate of 100%. There were 127 (42.6%) participants whose age ranged from 31 to 40 years old, and 84 (28.2%) respondents were aged between 21 and 30 years. Almost half of the participants 134(45.4%) were married, while 113 (38.9%) were single. 205 (70%) of participants had a secondary level of education and 41 (14%) had tertiary education (Figure 1-3).

Knowledge on malnutrition

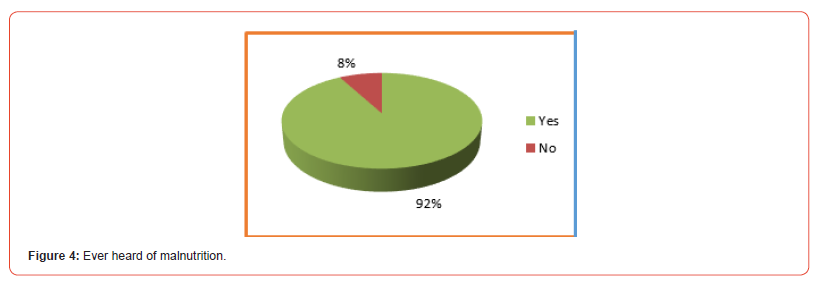

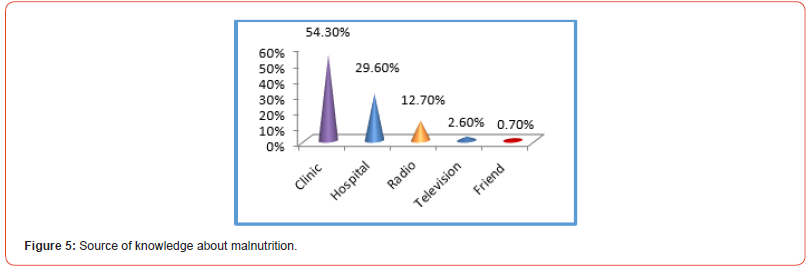

Figure 4 below indicates that 261(92%) respondents have heard about malnutrition, while 23(8%) never heard about it. Figure 5 indicates that 145(54.3%) participants had heard about malnutrition from the clinic and 79(29.6%) had got the information from the hospital. Significantly, radio was the third most common source of malnutrition information as reported by 34(12.7%) followed by television with 7(2.6%) respondents. Friends were the least source of knowledge with only 2(0.7%) respondents having obtained information this way (Figures 4&5) (Table 3).

Table 3 above indicates that the majority of participants (n=184; 62.8%) knew that lack of nutrients in the body as the cause of malnutrition, while 61(20.8%) thought that HIV/AIDS is the cause. Notably, 38(13%) respondents perceived that cholera is the cause of malnutrition, and 10(3.4%) said it was caused by diarrhea (Table 4).

Association between respondents’ level of education and knowledge of malnutrition causes: Table 4 above indicates a high number (116) of respondents with a secondary level of education reporting lack of nutrients in the body as the cause of malnutrition. Only 3 respondents who have been to school reported HIV/AIDS as the cause of malnutrition. Thus, there is a statistically significant relationship between the level of education and knowledge of the causes of malnutrition (p<0.001).

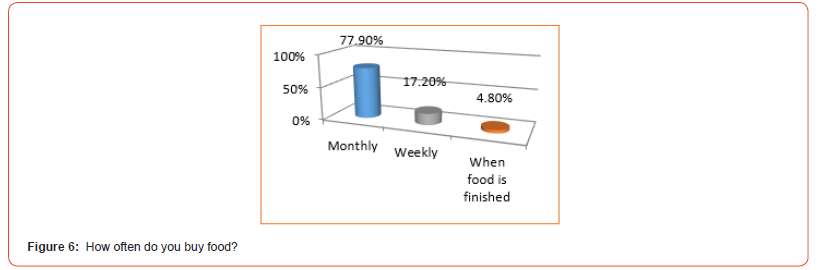

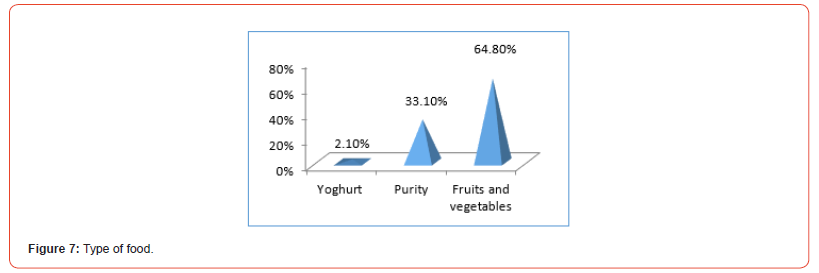

Malnutrition preventive practices: Table 5 shows that most participants 259(88.4%) knew that eating balanced diet can prevent malnutrition. Seventeen (5.8%) thought that malnutrition can be prevented by eating potatoes, whereas about 12(4.1%) thought that eating meat prevents malnutrition. Only a small proportion (n=5; 1.7%) of respondents thought that eating Simba prevents malnutrition. The majority of participants (64.8%) knew that fruits and vegetables are the best types of food to prevent malnutrition (Table 5) (Figures 6&7).

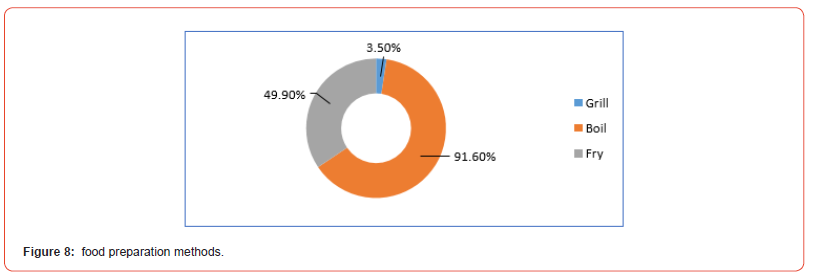

Food preparation knowledge: Figure 8 below reports food preparation practices where, most of the participants 263 (91.6%) knew that boiling is the best food preparation method. Only a small percentage 14(4.9%) of participants said thought that frying, and 10(3.5%) grilling were best methods (Figure 8).

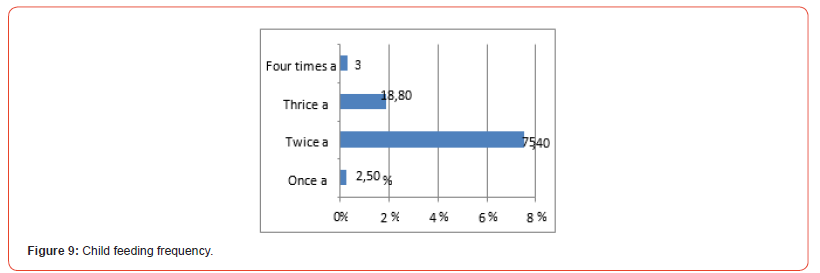

Feeding practices: When respondents were asked how often they feed their children, in figure 9, about 208(75.4%) of participants said they feed their children twice a day, while 52(18.8%) said they feed their children three times a day. Nine (3.3%) respondents said they feed their children four times a day. Only 7(2.5%) respondents said they feed their children once a day. Furthermore, respondents were asked to indicate the type of food they give their children, and response in Table 6 gave more than one answer. Overall, soft porridge was the most common food type given to children with 167 (58.4%) respondents. Cereals were the second common food type with 149 (52.1%) respondents and133 (46.5%) gave their children bread (Table 6) (Figure 9).

Association between respondents’ level of education and malnutrition prevention practices prevention: Table 7 shows that a high number of respondents (178) with secondary level education indicated that eating a balanced diet can prevent malnutrition. Only 3 respondents who have never been to school reported that eating meat every day prevents malnutrition. However, there is statistically a significant relationship between the level of education and the knowledge of malnutrition prevention (p<0.05) (Table 7).

Attitude towards malnutrition: Table 8 indicates that the majority (55.4%) of participants agree that they should feed their children 3-5 times a day. About 66.8% agree that it is their responsibility to buy healthy nutritious food. About 65% agree that they should always feed their children on a balanced diet. About 80.8% agree that it is their responsibility to avoid buying junk food for their children (Table 8).

The impact of knowledge and attitude on mothers’ malnutrition preventative practices using multiple regression test: Multiple regression was used to access the impact of knowledge and attitude on malnutrition preventive practices. Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity. Tables 9, 10, and 11 below provide the more details (Table 9).

The model summary shown in Table 9 shows that the multiple correlation coefficient R = 0.114 indicates a weak correlation between malnutrition, attitude, and knowledge. In terms of variability in observed malnutrition accounted for by the fitted model, this amounts to 0.013 or 1.3% (Table 10). Table 10 (ANOVA) does not show enough evidence to support a statistically significant relationship between malnutrition, attitude, and knowledge, since the F-test for the hypothesis is given by (F (2,174) =1.138, p>0.05 (Table 11).

Discussion

Knowledge of participants

Findings indicate that the majority (62.8%) of participants knew that lack of nutrients is the cause of malnutrition; about 88.4% knew that eating a balanced diet can prevent malnutrition; 88% knew that boiling is the best food preparation method; 64.8% knew that fruits and vegetables are the best to prevent malnutrition. Similar findings were discovered by [17] who indicated that majority 216 (62.2%) (95% CI = 56.9% - 67.4%)] of the respondents had good knowledge of factors associated with malnutrition. These findings concur with those by Cumber et al [18] who found that out of 120 mothers, 69 (57.5%) had adequate knowledge, 36 (30%) had somewhat adequate knowledge, and 15 (12.5%) had inadequate knowledge. Similarly, the study conducted by [19] revealed that most mothers (62.8%) know that a lack of nutrients in the body causes malnutrition. A similar study in India found that the majority 112(56%) of mothers had moderately adequate knowledge and moderately adequate practice 116(58%) regarding dietary practices in prevention of malnutrition [20].

Malnutrition prevention practices

About 75.4% of participants fed their children soft porridge twice a day compared to those who fed cereals (52.1%) and bread (46.5%). that caregivers were lacking knowledge regarding nutritious food to be given to their children [21]. A similar study by [22] indicates that maize meal porridge (87.5%) and bread (54.2%) were consumed daily by most of the children. A study by [23] confirms the findings by indicating that poor food diversity with low consumption of animal foods was observed for children aged six to 24 months. There was a significant relationship between malnutrition preventive practices and level of education at p<0.05. In addition, very few (4.8%) of participants could afford to buy additional food anytime they run out. These results are similar to the ones by [24] indicating that only 33.2% of households were food secure, 29.3% were at risk of hunger, and 37.5% experienced hunger [25,26].

Malnutrition preventive practices attitudes

Majority (55.4%) of participants agree that they should feed their children 3-5 times a day. About 66.8% agree that it is their responsibility to buy healthy nutritious food. About 65% agree that they should always feed their children on a balanced diet. About 80.8% agree that it is their responsibility to avoid buying junk food for their children. These findings are similar [27], who found that majority of mothers had fair to good KAP regarding nutrition of under-five children and prevention of malnutrition.

The impact of knowledge and attitude on mothers’ malnutrition preventative practices using multiple regression test

An analysis using multiple linear regression indicated that there is a linear relationship between knowledge, attitude, and malnutrition preventative practice but the relationship is not statistically significant (p-value=0.323). This means that health care workers should not trust that caregivers will practice good nutrition by virtue of them having adequate knowledge and attitudes. More efforts to keep monitoring and motivation should be done including addressing other determinants of poor feeding practices [28,29].

Limitations

The study cannot be generalized since it was only limited to the Thulamela Municipality of the Limpopo Province.

Conclusion

Mother of children under five years of age had moderate knowledge and positive attitudes towards malnutrition preventive measures. However, their malnutrition preventive practices such as choice of foods that constitute a balanced diet as well as feeding frequencies were not consistent with the level of knowledge and attitudes. This may be attributed to the fact that very few could afford to buy additional food anytime when they run out.

Recommendations

To address malnutrition in children under the age of five, the South African Department of Health should continue providing health promotion program targeting mothers. Social media should be used to ensure that all mothers and especially new mothers have access to information about malnutrition as well. Communities sensitized about the value of eating a healthy, nutritious, and balanced diet. The South African Department of Social Development should intervene to stop malnutrition by identifying households that are below the poverty line and giving them financial aid for nutrient-dense food. The South African Department of Basic Education should continue with the school nutrition programs and ensure that they run effectively. Communities should get training, information, and resources from the South African Department of Agriculture to effectively practice subsistence farming.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Adinma JI, Umeononihu OS, Umeh MN (2017) Maternal nutrition in Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 34(2): 79-84.

- Peter ES, Aliyu SH, Hassan RS (2019) Nutrition Assessment and Factors Influencing Malnutrition among Children under Five in Adjumani District Uganda. J Adv Med Res. Published online 30: 1-7.

- Labuschagne L (2022) Mothers and caregivers need nutrition education to protect children in food-insecure environment. Mail & Guardian.

- (2021) Global Nutrition Report: The state of global nutrition. Bristol, UK: Development Initiatives.

- Yan B, Vember H, Loots R (2021) Effectiveness of Intervention Practices in Preventing Childhood Malnutrition in a Semi-rural Area of the Western Cape. Child Care in Practice 14: 1-8.

- Wakeel A, Farooq M, Bashir K, Ozturk L (2018) Micronutrient malnutrition and bio fortification: recent advances and future perspectives. Plant micronutrients use efficiency 1: 225-43.

- (2022) UNICEF.

- Modjadji P, Molokwane D, Ukegbu PO (2020) Dietary diversity and nutritional status of preschool children in Northwest Province, South Africa: A cross sectional study. Children 7(10): 174.

- Dukhi N (2020) Global prevalence of malnutrition: evidence from literature. Malnutrition 1: 1-6.

- Senekal M, Nel JH, Malczyk S, Drummond L, Harbron J, et al. (2019) Provincial Dietary Intake Study (PDIS): Prevalence and Sociodemographic Determinants of the Double Burden of Malnutrition in A Representative Sample of 1 to Under 10-Year-Old Children from Two Urbanized and Economically Active Provinces in South Africa. International journal of environmental research and public health 16(18): 3334.

- Said Mohamed R, Micklesfield LK, Pettifor JM, Norris SA (2015) Has the prevalence of stunting in South African children changed in 40 years? A systematic review. BMC public health 15: 534.

- Das S, Gulshan J (2017) Different forms of malnutrition among under-five children in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study on prevalence and determinants. Bmc Nutrition 3(1): 1-2.

- Troeger C, Colombara DV, Rao PC, Khalil IA, Brown A et al. (2018) Global disability-adjusted life-year estimates of long-term health burden and undernutrition attributable to diarrhoeal diseases in children younger than 5 years. The Lancet Global Health 6(3): e255-e269.

- Ghosh S (2020) Factors responsible for childhood malnutrition: A review of the literature. Current Research in Nutrition and Food Science Journal 8(2): 360-70.

- Watkins K (2016) The State of the World's Children 2016: A Fair Chance for Every Child. UNICEF. 3 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017.

- Loots R, Yan B, Vember H (2021) Factors Associated with Malnutrition among Children Aged Six Months to Five Years in a Semi-Rural Area of the Western Cape, South Africa. Child Care in Practice 9: 1.

- Rao SA, Goswami BN, Sahai AK, Rajagopal EN, Mukhopadhyay P, et al. (2019) Monsoon mission: a targeted activity to improve monsoon prediction across scales. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 100(12): 2509-32.

- Guilford JP, Fruchter B (1973) Fundamentals statistics in psychology and education.

- Manohar B, Reddy NS, Vyshnavi P, Sruthi PS (2018) Assessment of knowledge, attitude, and practice of mothers with severe acute malnutrition children regarding child feeding. Int J Pharm Clin Res 10(5): 5.

- Cumber SN, Ankraleh N, Monju N (2016) Mothers’ knowledge on the effects of malnutrition in children 0–5 years in Muea health area Cameroon. Journal of Family Medicine and Health Care 2(4): 36.

- Edith M, Priya L (2016) Knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) survey on dietary practices in prevention of malnutrition among mothers of under-five children. 2(2): 19.

- Rodriguez OO, Barrera LS, Ospina JM (2019) Knowledge, attitudes and food practices in caregivers and nutritional status in infants from Ventaquemada, Boyaca, Colombia. Archivos de Medicina (Col) 19(1): 74-86.

- Clarke P, Zuma MK, Tambe AB, Steenkamp L, Mbhenyane XG (2021) Caregivers' Knowledge and Food Accessibility Contributes to Childhood Malnutrition: A Case Study of Dora Nginza Hospital, South Africa. International journal of environmental research and public health 18(20): 10691.

- Motebejana TT, Nesamvuni CN, Mbhenyane X (2022) Nutrition Knowledge of Caregivers Influences Feeding Practices and Nutritional Status of Children 2 to 5 Years Old in Sekhukhune District, South Africa. Ethiopian journal of health sciences 32(1): 103–116.

- Raji IA, Abubakar AU, Bello MM, Ezenwoko AZ, Suleiman ZB, et al. (2020) Knowledge of Factors Contributing to Child Malnutrition among Mothers of Under-five Children in Sokoto Metropolis, North-West Nigeria. Journal of community medicine and Primary Health Care 32(2).

- Kumwenda W. Parental and caregivers’ nutrition knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, and practices on infant and young child feeding (aged zero to 24 months) in Mzimba-north district, Malawi. Unpublished MSC nutrition dissertation.

- Thabathi TE, Maluleke M, Raliphaswa NS, Masutha TC (2022) Perceptions of Caregivers Regarding Malnutrition in Children under Five in Rural Areas, South Africa. Children 9(11): 1784.

- Srijat Dahal, Mausam Shrestha, Sanjeeb Shah, Babita Sharma, Mandip Pokharel, et al. (2020) Attitude and Practice Towards Malnutrition among Mothers of Sunsari, Nepal. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications 10(1): 178.

- Sangra S, Nowreen N (2019) Knowledge, attitude, and practice of mothers regarding nutrition of under-five children: A cross-sectional study in rural settings.

-

Ratshibvumo A Annah, Luhalima T Rhoda* and Tshitangano T Grace. The Impact of Mothers’ Knowledge and Attitudes on Malnutrition Prevention Practices Among Children Under Five in Thulamela Municipality, South Africa. Iris J of Nur & Car. 4(2): 2023. IJNC.MS.ID.000581.

-

Attitude, Children, Impact, Knowledge, Malnutrition prevention, Mothers, Thulamela Municipality, Pregnancy, Nutrition deficiency, Demographic data, Hypothesis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.