Research Article

Research Article

Strengthening Healthcare through Safe Staffing Levels: A European Policy Perspective on Safe Nurse-to- Patient Ratios and Workforce Sustainability

Paul De Raeve1*, Hannes Vanpoecke2,3*, Manuel Ballotta4, Andreas Xyrichis5, Yannai DeJonghe6 and Ivana Žilić7*

1EFN Secretary General at the European Federation of Nurses Associations, Belgium

2PhD-researcher at Department of Marketing, Innovation and Organisation, Ghent University, Belgium

3PhD-researcher at Center for Service Intelligence, Ghent University, Belgium

4EFN Policy Advisor at the European Federation of Nurses Associations, Belgium

5Reader at King’s College London, United Kingdom

6PhD-researcher at Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Ghent University, Belgium

7PhD Candidate in Nursing Care, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Maribor, Slovenia

Paul De Raeve, EFN Secretary General at the European Federation of Nurses Associations, Belgium

Received Date:June 25, 2025; Published Date:July 09, 2025

Introduction: Safe staffing levels (SSL) are essential to ensuring patient safety, nurse well-being, and health system resilience. Although a strong evidence base links nurse staffing to care quality, legislative and policy approaches across Europe remain inconsistent and fragmented.

Methods: This comparative policy analysis combined a structured literature review with primary data from the 2025 EFN Safe Staffing

Survey. Responses from 33 national nursing associations were analysed to explore the existence and nature of nurse staffing legislation, national

calculation methodologies, skill-mix frameworks, accountability systems, training provisions, and the role of professional associations. Findings

were supplemented by national legislative documents and policy reports.

Results: Out of 33 EFN member countries, 23 reported having legislation or formal policy on SSL, though legal enforceability and monitoring

mechanisms vary. Only nine countries apply a nationally approved methodology for staffing calculation. Fixed nurse-to-patient ratios are mandated

in a minority of jurisdictions, while most rely on flexible or needs-based models. National nursing associations play an active policy role in some

countries but remain marginalised in others. Few countries provide structured training or enforceable accountability measures. Protection for

nurses working under unsafe conditions is largely absent.

Discussion: The results highlight major gaps between policy aspirations and implementation. While progress is evident, many European

countries still lack robust legal and institutional frameworks to ensure safe staffing. Strengthening SSL governance requires harmonisation,

enhanced data systems, and greater involvement of the nursing profession in shaping policy.

Keywords:Safe staffing levels; Nurse-to-patient ratios; Nursing legislation; Health workforce governance; Skill mix; National nursing associations; Healthcare policy; EFN survey; Patient safety; Comparative policy analysis

Introduction

In a continuously changing world, adequate policy responses are essential, especially when it comes to strengthening healthcare systems across the European Union. To ensure a resilient and equitable healthcare ecosystem, it is crucial to invest in a welleducated nursing workforce and to guarantee safe staffing levels and working conditions that support both care quality and workforce sustainability.

A growing body of research has consistently shown that higher nurse staffing levels and appropriate skill mix are strongly associated with improved patient outcomes, reduced mortality, and enhanced nurse well-being [1-4]. Systematic reviews and large observational studies across various countries confirm that inadequate staffing leads to higher rates of in-hospital deaths, infections, falls, missed care, and adverse events [3,5]. As a result, safe nurse staffing is increasingly recognised not only as a clinical issue but as a matter of patient safety, ethical healthcare, and workforce protection.

The burden of insufficient staffing falls heavily on nurses, with excessive workloads being strongly associated with increased clinical errors, moral distress, and burnout. This places nurses’ well-being and patient safety at risk [6,7]. Nurses working under such high-pressure conditions are more likely to experience emotional and physical exhaustion, which contributes to higher turnover rates and deepens existing workforce shortages.

The World Health Organization (WHO) projects a shortfall of nearly 1.8 million healthcare professionals in Europe by 2030, with nurses representing the majority of this deficit [8]. Already today, Member States are experiencing consequences such as unsafe care environments, increased staff turnover, and declining interest in the nursing profession. These elements are contributing to a vicious cycle. The deterioration in working conditions and job satisfaction leads to even higher turnover and reduced interest in entering the profession—further deepening the staffing crisis [9]. Breaking this cycle requires urgent, systemic action to support and sustain the nursing workforce.

Safe staffing levels (SSL) are defined as the appropriate number and mix of nurses required to meet patients’ needs safely and effectively. While patient acuity tools have been developed in many countries to guide workload distribution, evidence shows they are not effective unless combined with legislated nurse-to-patient ratios. Acuity tools alone do not ensure safe conditions if staffing baselines are not guaranteed [10].

Beyond individual outcomes, SSL also contributes to healthcare system resilience and financial sustainability by reducing hospitalacquired complications and unnecessary readmissions [11] (McHugh et al., 2019). Countries such as Australia and the United States have introduced legislation mandating minimum nurse-topatient ratios, showing positive results in nurse retention, patient satisfaction, and cost-efficiency (Twigg et al., 2013; McHugh et al., 2019). Importantly, these models are not “one-size-fits-all”: They vary by type of unit and care setting, allowing flexibility while maintaining essential safety thresholds [12].

In contrast, EU countries lack harmonised legislation, and the implementation of SSL varies widely across national and regional contexts. Some rely on voluntary frameworks or internal tools, while others lack any formal staffing methodology or regulatory oversight [13,14]. This fragmented approach creates significant disparities in care quality and staff safety across Europe.

Despite the existing evidence, several challenges persist in establishing safe nurse staffing policies. These include political reluctance, cost concerns, decentralised governance structures, and chronic shortages of nursing personnel. Furthermore, the lack of standardised data collection and transparent monitoring hinders accountability. Notably, legislation on safe staffing levels protects frontline nurses by shifting accountability to employers through mandatory reporting systems, offering a legal safety net [10].

The European Federation of Nurses Associations (EFN), representing over 3 million nurses across 36 European countries, has been advocating for the inclusion of SSL in EU legislation for more than a decade. In its recent Policy Statements [13,14], EFN emphasises that nurse staffing is not only a workforce issue but a fundamental human right, linked to dignity, safety, and quality of care. It also highlights the ethical problems posed by the overreliance on international recruitment to fill domestic staffing gaps, especially when sourced from countries already facing health workforce shortages.

To support this advocacy, the EFN developed a Policy Brief [10] based on data collected from its members and national nursing associations. The brief synthesises evidence, identifies good practices, and outlines actionable recommendations for policymakers. It reveals a concerning picture: while some countries have made efforts to regulate staffing levels, many still operate without enforceable standards or systematic evaluation. Furthermore, the absence of legal frameworks makes it difficult to respond effectively to emerging challenges such as demographic ageing, multimorbidity, or health emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic.

This article builds upon EFN’s policy work by translating its core findings into an academic format. It aims to inform both policymakers and academic audiences about the necessity of coordinated EU-level legislation on safe staffing levels. By combining policy analysis with a synthesis of best practices and international comparisons, the article makes a compelling case for recognising SSL as a cornerstone of sustainable healthcare systems.

Safe nurse staffing is no longer a question of professional advocacy alone—it is a public health priority. The evidence is clear, the stakes are high, and the time for action is now.

Methods

This study employed a descriptive, exploratory policy analysis

based on two primary sources of data:

1) A structured desk review of scientific and grey literature,

and

2) A survey-based inquiry conducted by the European

Federation of Nurses (EFN) across its national member

associations.

The objective was to map the current status of Safe Staffing Level (SSL) policies in Europe, identify implementation trends and gaps, and examine the role of National Nursing Associations (NNAs) in shaping safe staffing legislation and practice.

A structured desk review was conducted between November 2024 and February 2025 to synthesise available evidence on nurse staffing, skill mix, and healthcare outcomes. This phase was carried out simultaneous with the development and dissemination of the EFN member survey to ensure that the survey instrument was informed by current knowledge and policy debates.

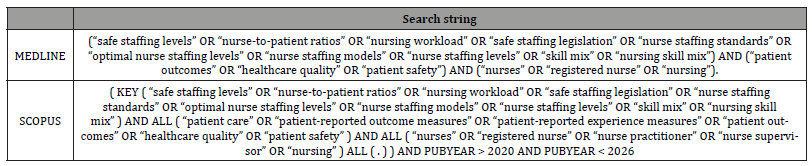

Searches were performed in Medline and Scopus using a search string developed and validated by two researchers (see Table 1). The inclusion criteria were: (1) Systematic or high-quality narrative reviews; (2) Focus on nurse staffing, skill mix, and patient outcomes; (3) Published between 2021 and 2025; (4) English or Dutch language; and (5) Geographical focus on Europe, the United States, Canada, the UK, Australia, Japan, China, and South Korea.

The initial search retrieved 247 records. After title, abstract, and full-text screening, and the removal of duplicates and nonreview papers, 16 reviews were retained for thematic synthesis. Only nine of these directly addressed staffing legislation, ratios, or skill mix standards.

To complement peer-reviewed sources, a targeted search for grey literature was conducted. This included: (1) EFN policy statements, white papers, and briefings; (2) National legislation, staffing regulations, and official government reports; (3) Position statements and toolkits published by NNAs, ministries of health, and international bodies (e.g., WHO, ICN); (4) Reference tracking from included reviews (snowballing approach); and (5) Targeted keyword-based searches on official websites of European health authorities and professional organisations.

The combined findings informed the construction of the analytical framework for categorising survey responses.

Following the initial desk review, a structured survey was administered to all 35 EFN member countries between 25 November 2024 and 3 February 2025. The survey was designed to collect comparative, country-level data on: (1) Existence and nature of SSL legislation; (2) Methodologies used to calculate staffing levels and skill mix; (3) Types of tools available at national or institutional levels; (4) The role and involvement of NNAs in policymaking; (5) Training and implementation mechanisms; and (6) Systems for reporting staffing violations and accountability provisions.

The survey comprised eight open-ended questions, drafted by the EFN Secretariat and reviewed by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. A total of 33 countries submitted complete responses, which included both narrative descriptions and, in many cases, supporting documentation (laws, frameworks, agreements, tool specifications).

Survey respondents were senior representatives of NNAs, submitting data with institutional consent. Where applicable, responses were supplemented with external documents for validation.

Data analysis

The analysis combined descriptive statistics and thematic coding.

Quantitative data from closed survey items (e.g., presence or absence of legislation, tool availability) were summarised using frequency counts and percentages.

Qualitative data, including open-ended survey responses

and policy documents, were analysed using a deductive thematic

approach based on five predefined categories:

(1) Legal frameworks and legislative instruments

(2) Staffing calculation methods and planning tools

(3) Accountability and escalation mechanisms

(4) Role of NNAs in policy development and governance

(5) Availability of training and implementation support

Manual coding was performed independently by two researchers, with iterative comparison and refinement to ensure analytical coherence.

The integration of data sources (survey, literature, grey documentation) was achieved through triangulation to identify cross-cutting themes, policy gaps, and areas of convergence between evidence and practice.

Ethical considerations

This study did not involve human subjects or patient-level data.

All data sources were either:

• Publicly accessible, or

• Provided by EFN member institutions with their consent

for analysis and publication.

As such, ethical approval was not required under current European research guidelines.

Results

Findings from the literature review

The desk research yielded 247 articles, from which 47 were selected for full-text review. The literature review identified substantial international variation in nurse staffing levels, policy approaches, and skill-mix regulations. Sixteen systematic reviews and key national reports were analysed, highlighting two dominant regulatory models for nurse staffing: fixed minimum nurse-topatient ratios and flexible, needs-based models. Additionally, innovative staffing tools and skill-mix requirements were explored, though evidence remains fragmented and inconsistent.

Nurse-to-patient ratios

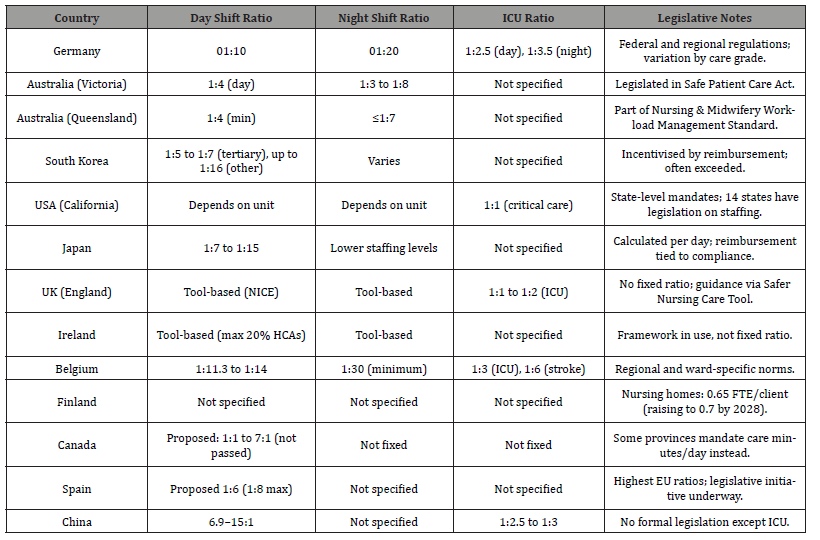

Research on nurse staffing levels at a global scale highlights a focus on general hospital wards significant variations, and the intensive care unit (ICU). General hospital wards show wide disparities: daytime ratios range from 1:3 to 1:10, while night shifts may exceed 1:18 (Ball et al., 2021) [15-17], (Table 2). ICU ratios on the other hand, have a commonly observed standard of 1:1 or 1:2 globally, with some variation depending on national policies, resource availability, and workforce planning (Adynski et al., 2022; Falk et al., 2022) [1].

Table 1:Search string.

Table 2:Comparative country analysis of minimum hospital staffing standards across selected countries.

Nurse-to-patient ratio legislation has only been enacted in a minority of countries and regions. For example, Belgium, California, Victoria and Queensland have mandated ratios, while UK, Germany, and Japan apply national or regional tools or reimbursement-based incentives. The ICN [18] and EFN [19] have repeatedly called for legally binding staffing standards, particularly in acute and longterm care settings.

Other staffing approaches and tools

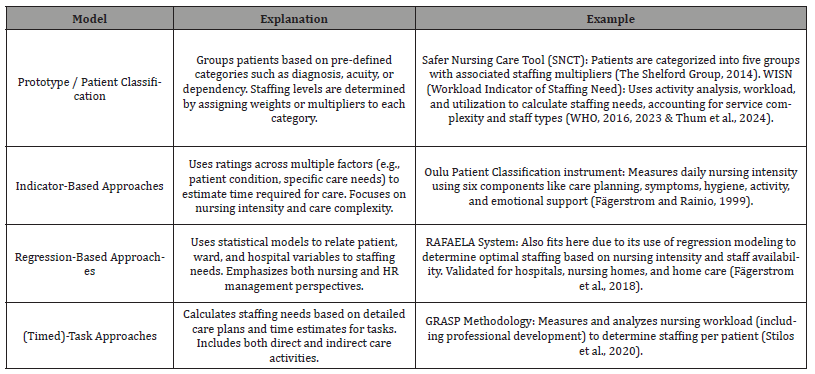

In contrast to these fixed minimum ratios, countries like the United Kingdom and Ireland rely on more flexible, needs-based methodologies that utilize internal staffing committees and validated patient acuity tools to determine appropriate staffing levels. These models are categorised by Griffiths et al. (2020) in four categories: 1) Patient/prototype approaches, 2) Indicatorbased approaches, 3) Regression-based approaches and 4) Timedtask approaches (Table 3). Other approaches include budget-based, benchmarking, team based and professional judgement approaches (Griffiths et al., 2020) [20].

Commonly used tools include the Safer Nursing Care Tool (SNCT), Workload Indicators of Staffing Need (WISN), and the RAFAELA system. These tools integrate clinical factors such as patient acuity, complexity of care, and task-based metrics to estimate optimal staffing needs (Griffiths et al., 2020) [8]. While they can enhance local decision-making, their effectiveness is often constrained by implementation fidelity and contextual barriers. Recently, interest has grown in AI-based dynamic staffing models. Studies show positive effects on health outcomes and patient satisfaction, but widespread adoption remains limited due to technological infrastructure demands and gaps in digital literacy (Schäfer et al., 2023 & Othman et al., 2025).

Table 3:Needs-based methodology approaches.

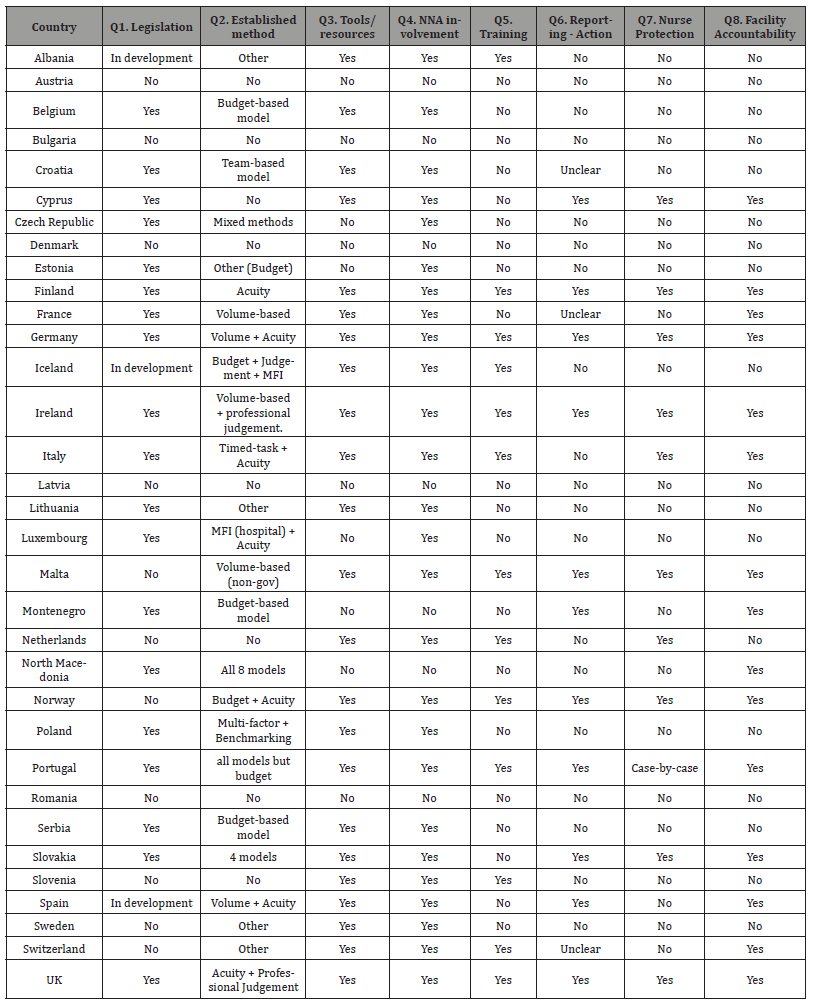

Table 4:Overview of nurse staffing legislation, methodologies, and governance elements in 33 EFN member states (2025 survey data).

Non-hospital healthcare facilities

There is little evidence on optimal staffing levels in nursing homes, long-term care facilities and home nursing. Some legislations are in place (e.g. South-Korea, USA, Belgium, Finland and Canada (Alberta, British Colombia and Ontario) but vary in staffing levels [21-23]. Due to the complex needs of elderly, or people with disabilities or chronic illnesses, the staffing is determined by a multidisciplinary direct care team instead of only nurses. Included in these direct care teams are for example caregivers, personal care aides, home health aides [24] (Annear et al., 2016). The direct care workers-to-resident ratios range from 1:2-1:40 in night shifts. The RAFAELA instrument is the only flexible staffing approach that is also validated for nursing homes and home care (Flo et al., 2018).

Skill-mix ratios

Only a few countries explicitly regulate nurse skill-mix, despite its known impact on care quality and cost-efficiency. Ireland, for instance, mandates a staffing ratio of 80% Registered Nurses (RNs) to 20% Health Care Assistants (HCAs) (Brady et al., 2025). California limits Licensed Practical Nurses (LPNs) to 50% of the nursing team, while Victoria requires a minimum of 80% RNs. In Queensland, only RNs and Enrolled Nurses (ENs) are considered in official staffing calculations.

Evidence suggests that higher RN proportions, typically 80– 85%, are associated with improved patient outcomes, shorter hospital stays, and lower overall healthcare costs (Li et al., 2025). However, systematic reviews remain inconclusive about the optimal skill-mix proportions due to methodological variability and the complexity of cross-national comparisons [16,25].

Despite a substantial body of evidence linking nurse staffing and skill mix to improved patient safety and nurse well-being, significant gaps persist in research and policy implementation. Notably, there is no harmonised EU legislation mandating safe staffing levels or defining skill-mix standards. Many countries lack integrated data systems for collecting and analysing staffing metrics, which hinders transparency and evidence-informed policy-making. Furthermore, the long-term care sector remains underrepresented in both research and legislative efforts, despite its increasing importance due to demographic ageing. Finally, inconsistencies in terminology, measurement tools, and outcome indicators limit the comparability of studies across countries, posing challenges for international benchmarking and policy harmonisation.

Survey findings from EFN member states

In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the current state of nurse staffing legislation and governance across Europe, the European Federation of Nurses Associations (EFN) conducted a structured survey addressed to all 35 of its member organisations. By the end of the data collection phase in February 2025, 33 countries had submitted valid responses. The survey instrument, consisting of eight open-ended questions, aimed to explore the existence and scope of national legislation on Safe Staffing Levels (SSL), methodologies for calculating staffing needs, the involvement of national nursing associations (NNAs), training provisions, and mechanisms for accountability.

A full comparative overview of country-level responses is provided in Table 4, summarising the key dimensions of nurse staffing governance across the 33 responding EFN member states. This table synthesises survey results on the existence of legislation, staffing methodologies, tool availability, NNA involvement, training, reporting procedures, nurse protection, and facility accountability.

Of the 33 respondents, 23 countries reported having in place either a legislative instrument, a formal policy framework, or a government-supported initiative aimed at defining and promoting safe nurse staffing. However, the nature and enforceability of these frameworks vary significantly. Binding legal provisions with specified nurse-to-patient ratios were reported in countries such as Belgium and Germany, where legislation mandates minimum standards and includes monitoring mechanisms. In contrast, countries such as Finland and Portugal reported having national guidelines or policy declarations that outline principles for staffing but do not impose legal obligations or include sanctions for noncompliance.

Several countries described fragmented governance structures. For example, in Italy, staffing policies differ across regions, reflecting the decentralised nature of the healthcare system. Similarly, in Bulgaria and Latvia, national frameworks are still under development, with nurse staffing discussed in strategic planning but without concrete regulatory instruments. In Lithuania, the absence of binding legal instruments was noted, despite existing policy-level discussions.

Only nine countries reported using a nationally endorsed and government-approved methodology for calculating staffing levels or defining appropriate skill mix. The methodologies applied include a diverse range of models, reflecting varying degrees of complexity and reliance on data systems. For instance, Austria reported the use of budget-based and professional judgement models, whereas Belgium relies on a combination of patient acuity scoring and multi-factorial indicators integrated into hospital workflows. Cyprus described the application of benchmarking methods, supported by national authorities.

In Finland, the RAI model is used nationally to assess client needs in long-term care settings, though it is not formally linked to dynamic daily staffing adjustments.

In Germany, a range of methodologies is used, including patient classification tools and volume-based indicators, but integration into national digital infrastructure was not confirmed.

Ireland and Portugal employ hybrid models, combining volume-based inputs with patient condition indicators to establish minimum staffing standards. Slovakia applies four staffing models, including professional judgement, acuity-based, and volume-based approaches. Serbia mentioned the use of professional judgement tools, although respondents noted variability in their application and limited formal oversight.

In countries without an approved methodology, hospitals or health systems may resort to legacy models, internal benchmarks, or managerial discretion, raising concerns about transparency and consistency in staffing decisions.

The degree of involvement of NNAs in policymaking and governance processes related to staffing was found to be highly variable. In countries such as Ireland, the Netherlands, and Slovenia, NNAs play an active role in policy development, contributing empirical expertise, participating in regulatory consultations, and occasionally co-authoring legislative proposals. These NNAs often engage in structured dialogue with ministries of health and other stakeholders, positioning themselves as authoritative voices in workforce planning.

The survey revealed that few countries offer structured training programmes to support the implementation of safe staffing methodologies. Sweden and Norway were among the exceptions, with established leadership development initiatives that include content on staffing policy, workload measurement, and team planning. These programmes are typically embedded in continuing professional development curricula for nurse managers and health administrators.

Elsewhere, most respondents noted a lack of formal education or training on SSL, even in contexts where staffing models are available. This mismatch between policy ambition and implementation capacity was frequently identified as a barrier to the effective use of staffing tools. The absence of such training was particularly pronounced in countries with decentralised or emerging regulatory frameworks.

Formal systems for monitoring compliance with staffing standards and addressing breaches were largely absent or underdeveloped in most countries. Only a few respondents, particularly from Finland, Belgium, and the United Kingdom (specifically Wales), reported the existence of structured reporting protocols and accountability frameworks. For example, Wales integrates escalation pathways into its statutory staffing law, allowing staff to report unsafe conditions with the expectation of institutional response.

Equally concerning is the widespread absence of legal protections for nurses who are forced to work under unsafe staffing conditions. Very few countries have established liability waivers or formal statements of organisational accountability, leaving individual professionals vulnerable to blame in the event of adverse outcomes. This lack of institutional responsibility not only undermines professional safety but also erodes trust in the healthcare system’s ability to respond equitably to systemic challenges.

The results of the 2025 EFN survey illustrate both progress and persistent gaps in the development of SSL governance across Europe. While a growing number of countries have introduced policies or legislation to regulate staffing levels, these efforts are fragmented and uneven in their scope and implementation. The limited use of government-endorsed methodologies, the variable involvement of nursing associations, the scarcity of training provisions, and the near absence of enforceable accountability measures all contribute to a policy landscape that is still evolving, and in many cases, inadequate to meet the demands of modern healthcare systems.

These findings call for strengthened coordination at both the national and European levels, with an emphasis on standardisation, nurse leadership, and cross-country learning. They also highlight the importance of protecting frontline nurses from the legal and ethical burdens associated with systemic understaffing. Only through such comprehensive reform can safe staffing be realised as a cornerstone of quality, safety, and sustainability in European healthcare.

Policy context from EFN position documents

Findings from the survey were reinforced by analysis of EFN policy outputs, particularly the EFN Policy Statement on Safe Staffing Levels [26], the EFN Policy Statement on the EU Nursing Workforce within a Global SSL Context [27], and the EFN Policy Brief on Safe Staffing Levels [28].

These documents highlight that:

• Only a minority of Member States have legal frameworks

or national methodologies for nurse staffing.

• The majority rely on local-level, non-binding approaches,

with limited or no central oversight.

• Ethical concerns, such as nurse burnout or the right

to refuse unsafe workloads, are largely absent from policy

discussions.

• Some governments continue to rely on international

recruitment without safeguards, exacerbating global

inequalities in health workforce distribution.

The EFN documents emphasise the urgent need for an EU-wide directive that recognises safe staffing as a human rights issue and sets safe staffing standards across Member States, with robust mechanisms for enforcement and data collection.

The combination of literature review, survey data, and EFN policy analysis leads to a consistent conclusion: nurse staffing across Europe remains inadequately regulated and under-monitored. Although evidence for the impact of safe staffing is strong, national responses are fragmented and non-cohesive. Without binding EUlevel legislation, disparities in workforce protection and patient safety are expected to widen.

Limitations

This study is subject to several limitations that affect both the desk research and the survey-based components.

First, there is a notable scarcity of recent, comprehensive, and peer-reviewed research focusing specifically on nurse staffing legislation and optimal skill-mix configurations across European countries. Much of the existing literature has focused on the consequences of inadequate staffing, particularly in terms of patient safety, mortality, and quality of care, rather than on defining or validating evidence-based standards for staffing levels or skill-mix ratios. Furthermore, the majority of studies are hospital-centric, while long-term care, primary care, and community health settings remain under-researched despite their increasing relevance.

Second, there is considerable heterogeneity in the definitions, staffing models, regulatory structures, and research methodologies across countries. The classification of nursing roles (e.g., RNs, LPNs, healthcare assistants), the understanding of “skill mix,” and the thresholds for “safe staffing” vary widely. This variability hampers comparability and synthesis of findings, and limits the ability to generalise conclusions or formulate harmonised European recommendations.

Third, the literature search was conducted primarily in English and Dutch. While efforts were made to access grey literature and policy documents, relevant sources published in other languages may have been missed, particularly in countries where national legislation is not translated into English or is not publicly available.

To address some of the limitations associated with secondary data sources, this study incorporated first-hand data collected through the 2025 EFN survey. The survey was disseminated to all 35 EFN member countries, inviting national nursing associations to provide structured responses regarding the status of nurse staffing legislation, policy frameworks, implementation mechanisms, and the involvement of professional bodies. By the end of the data collection period, 33 countries had submitted valid responses, which were subsequently enriched with national policy documents and legislative excerpts. Despite this, the primary data collection process is not without limitations. As the survey relied on voluntary self-reporting, there remains a risk of reporting bias, interpretative discrepancies, and inconsistent access to official sources across countries.

The EFN survey relied on self-reporting by national nursing associations and designated EFN representatives. This introduces the potential for reporting bias, incomplete responses, or differing interpretations of survey questions. In some cases, survey participants may have lacked access to official legislative texts or may have provided responses based on perception rather than verified documentation. Additionally, countries with inactive EFN members or limited organisational capacity were underrepresented or entirely absent, most notably Greece and Hungary, which submitted no data.

The study did not incorporate economic modelling or patientlevel outcome data, which would strengthen the policy case for legislated staffing ratios. Nor did it explore in depth the political, institutional, or cultural barriers to implementing SSL legislation, which remain key challenges in many Member States.

Despite these limitations, the integration of survey data with a structured policy review provides valuable insights into the fragmented nature of safe staffing legislation in Europe and offers a timely foundation for further comparative and policy-oriented research.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study presents the first comprehensive cross-national policy and literature-based analysis of Safe Staffing Levels (SSL) and nurse skill mix across Europe. Based on structured responses from 33 EFN member countries and an extensive review of the scientific and grey literature, the findings expose a persistent and systemic disconnect between the evidence supporting adequate nurse staffing and the current status of legislation, policy frameworks, and implementation strategies.

Although decades of empirical research confirm the association between adequate nurse staffing and improved patient outcomes, reduced nurse burnout, and greater health system resilience [29] (McHugh et al., 2019; Aiken et al., 2023), progress in Europe remains fragmented. By 2025, 23 countries reported having some form of legislation or national framework on SSL or were in the process of developing one—more than double the 11 countries reported in 2023. These include countries such as Germany, Finland, and Portugal, which have adopted structured approaches involving patient acuity and skill mix assessments, while others— such as Belgium and Italy—have introduced broader frameworks that vary in enforceability.

However, the implementation of SSL remains limited in scope. In most European countries, staffing policies are non-binding or lack accountability mechanisms, and only a few incorporate systematic tools or transparent monitoring structures. By contrast, countries such as California and Queensland have introduced enforceable nurse-to-patient ratios and demonstrated measurable improvements in care quality and nurse retention (Twigg et al., 2013; McHugh et al., 2019).

Another critical issue is the limited inclusion of nurses and their professional organisations in policymaking. According to EFN data, National Nursing Associations (NNAs) are often only consulted informally, if at all, during the development of staffing frameworks. This exclusion undermines the legitimacy, contextual relevance, and practical application of policy measures. The literature reinforces that participatory governance structures enhance policy implementation and alignment with frontline realities [12] (Drennan et al., 2023).

Ethical concerns also emerge prominently. Chronic understaffing contributes to moral distress among nurses and jeopardises patient safety, yet national staffing frameworks rarely acknowledge SSL as a human rights issue. Many policies frame staffing as a technical or financial matter, omitting its ethical and professional dimensions. Addressing these blind spots is critical, particularly in light of evidence linking inadequate staffing to missed care, adverse events, and workforce attrition.

While the increase in countries with SSL legislation or

frameworks is a positive trend, Europe still lacks a coordinated,

enforceable, and ethically grounded policy approach. The European

Commission has the opportunity to lead the way by introducing an

EU-level directive on Safe Staffing Levels, much like the Working

Time Directive. This directive should incorporate:

• Safe nurse-to-patient ratios tailored to care settings

• Skill mix standards reflecting evidence-based workforce

models

• Obligatory participation of nursing representatives in all

stages of policy development

• Monitoring systems tied to funding and performance

reporting (e.g., through the European Semester).

The study also highlights the urgent need for further research to develop harmonised indicators for SSL, explore economic and ethical implications of staffing models, and expand evidence for community and long-term care settings, where data remain scarce.

Safe nurse staffing is not only a workforce issue but a public health imperative. Without binding legislation, transparent mechanisms, and the active involvement of nurses in shaping policies, European health systems will continue to face risks to care quality, nurse well-being, and patient safety. This study provides a data-driven and ethically grounded call to action: policymakers, healthcare leaders, and professional bodies must move from aspiration to action, ensuring that every patient receives care from an appropriately staffed and qualified nursing workforce.

Recommendations

Building on the growing body of evidence and best practices identified in Section 3, the following comprehensive, multi-level recommendations are proposed. They aim to transition from fragmented and reactive approaches toward a cohesive and sustainable safe staffing framework that protects both patients and nurses across Europe.

Policy-level recommendations EU-level action

A coordinated EU-wide approach is essential to create a

sustainable and equitable framework for Safe Staffing Levels (SSL).

The EU should:

(1) Adopt a binding Directive on Safe Staffing Levels,

establishing safe nurse-to-patient ratios tailored to different

care settings and acuity levels, while allowing for limited

national adaptation.

(2) Integrate SSL indicators into EU governance tools, such as

the European Semester, EU4Health, Horizon Europe, and ESF+

funding streams.

(3) Establish a central EU monitoring and support structure,

ensuring implementation across Member States with

consequences for non-compliance.

(4) Develop a complementary Directive on Psychosocial

Risks, formally recognizing unsafe staffing as a contributor to

occupational harm among nurses.

Sustainable financing

(1) Create a dedicated EU Healthcare Workforce Capacity

Fund, providing targeted support for implementation of SSL

and retention strategies.

(2) Encourage Member States to invest in staffing as a longterm

cost-saving and quality-enhancing strategy.

Harmonised metrics and data infrastructure

(1) Standardise definitions and metrics related to staffing

levels, skill mix, and patient acuity to enable meaningful crosscountry

comparisons.

(2) Develop accessible reporting systems for staffing levels,

outcomes, and safety alerts, supporting transparency, early

warnings, and public accountability.

National-level recommendations Legislation and enforcement

National governments should:

(1) Enact or strengthen national laws mandating safe staffing

levels, appropriate skill mix, and transparent monitoring

systems.

(2) Ensure ethical principles are embedded into staffing

regulations, promoting workforce justice, equity of care, and

protection of nurses.

Capacity-building and resilience

(1) Develop robust national databases to support real-time

monitoring and performance improvement.

(2) Legislate accountability mechanisms that ensure staffing

adequacy and safeguard nurses from legal liability when

working in understaffed conditions.

Recommendations for healthcare institutions Operational implementation

Healthcare providers should:

(1) Use validated, dynamic workload assessment tools that

consider real-time patient acuity and team composition.

(2) Ensure transparency in staffing decisions, including

escalation protocols when staffing levels are unsafe.

(3) Align staffing with care complexity, promoting healthy

work environments and interprofessional collaboration.

Nurse protection and support

(1) Formalise organisational responsibility for staffing

decisions and introduce liability waivers to protect nurses

working in understaffed settings.

(2) Implement training for nurse managers in staffing

methodologies and workforce planning, including digital tools

and decision support systems.

Role of professional and regulatory bodies National Nursing Associations (NNAs)

NNAs should:

(1) Institutionalise the role of frontline nurses as co-creators

of staffing policy through inclusive governance structures.

(2) Develop educational resources and toolkits to support

staffing advocacy, implementation, and workplace negotiation.

(3) Support research into advanced roles and skill mix

models, including APNs, HCAs, and team-based care delivery.

Research priorities

Despite strong evidence supporting safe staffing, critical gaps

remain:

(1) Extend research to community, home, and long-term care

settings, which remain underexplored.

(2) Investigate the role of advanced practice nurses (APNs) in

optimising staffing models and patient outcomes.

(3) Standardise SSL indicators and definitions, enabling

stronger international benchmarking.

(4) Explore ethical and psychosocial impacts of unsafe

staffing on patients and nurses.

(5) Apply implementation science to identify strategies for

embedding evidence-based staffing models under resource

constraints.

(6) Promote inclusion of non-English literature and

underrepresented regions to strengthen global relevance.

Implementation roadmap

To achieve sustainable change:

(1) Short-term: Establish working groups at EU and national

levels, including nurses and stakeholders, to draft SSL

legislation.

(2) Medium-term: Launch formal legislative processes,

implement monitoring systems, create the EU Capacity Fund,

and adopt nurse protection protocols.

(3) Long-term: Ensure full integration of SSL in all healthcare

settings, supported by predictive workforce modelling that

reflects demographic and technological trends.

Safe Staffing Levels represent not only a technical aspect of workforce planning, but a core determinant of healthcare quality, equity, and sustainability. The findings of this study confirm that while evidence supporting safe staffing is abundant, policy implementation remains fragmented and insufficient across the EU. Without coordinated legal action, strategic investment, and full integration of nursing voices into policy-making, staffing disparities will persist, jeopardising care quality, professional retention, and public trust in health systems.

This paper contributes to the growing policy discourse by presenting data-driven, ethically grounded, and pragmatically framed arguments for advancing SSL regulation in Europe. It serves as a call to action for the European Commission, Member States, and healthcare leaders to translate evidence into enforceable, context-sensitive, and inclusive policy reform [30-56].

Funding Acknowledgments

Disclaimer: This work has been developed towards the Nursing Action, a WHO-led project funded by the European Commission. This article does not represent the view of the European Commission or WHO.

References

- Dall Ora C, Saville C, Rubbo B, Turner L, Jones J, et al. (2022) Nurse staffing levels and patient outcomes: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies 134: 104311.

- Griffiths P, Maruotti A, Recio Saucedo A, Redfern OC, Ball JE, et al. (2019) Nurse staffing, nursing assistants and hospital mortality: retrospective longitudinal cohort study, BMJ Quality & Safety 28(8): 609–617.

- Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, Van Den Heede K, Griffiths P, et al. (2014) Nurse staffing and education and hospital mortality in nine European countries: A retrospective observational study. The Lancet 383(9931): 1824–1830.

- Ball J, Catton H (2011) Planning nurse staffing: are we willing and able?. Journal of Research in Nursing 16(6): 551-558.

- Aiken L et al. (2021) Effects of nurse-to-patient ratio legislation on nurse staffing and patient mortality, readmissions, and length of stay: A prospective study in a panel of hospitals.

- Ball JE, Murrells T, Rafferty AM, et al. (2014) Care left undone’ during nursing shifts: associations with workload and perceived quality of care. BMJ Quality & Safety 23: 116-125.

- Phelan A and McCarthy S (2016) Missed Care: Community Nursing in Ireland. University College Dublin and the Irish Nurses and Midwives Organisation, Dublin.

- WHO (2022) Ticking timebomb: Without immediate action, health and care workforce gaps in the European Region could spell disaster.

- Lasater KB (2025) Eliminating hospital nurse understaffing is a cost-effective patient safety intervention. BMJ Quality & Safety, bmjqs-018677.

- Aiken L (2025) Safe staffing: Protecting the health and safety of nurses and patients (Policy Brief). Center for Health Outcomes and Policy Research, School of Nursing, University of Pennsylvania.

- Dall Ora C, Ball J, Reinius M, et al. (2020) Burnout in nursing: a theoretical review. Human Resources for Health 18(1): 41

- Buchan J (2024) Navigating nurse safe staffing approaches in the UK. The Health foundation.

- EFN (2023) EFN Matrix 3+1.

- EFN (2024) EFN Policy Statement on EU Nursing Workforce within a Global Safe Staffing Levels Context.

- McHugh MD, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Windsor C, Douglas C, et al. (2021) Effects of nurse-to-patient ratio legislation on nurse staffing and patient mortality, readmissions, and length of stay: a prospective study in a panel of hospitals. The Lancet 397(10288): 1905–1913.

- Twigg DE, Kutzer Y, Jacob E, Seaman K (2019) A quantitative systematic review of the association between nurse skill mix and nursing‐sensitive patient outcomes in the acute care setting. Journal Of Advanced Nursing 75(12): 3404–3423.

- Morioka N, Okubo S, Moriwaki M, Hayashida K (2022) Evidence of the Association between Nurse Staffing Levels and Patient and Nurses’ Outcomes in Acute Care Hospitals across Japan: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 10(6): 1052.

- ICN (2023) New ICN position statement highlights safe staffing and health workforce safety as priority areas for patient safety. ICN - International Council of Nurses.

- EFN (2022) EFN Policy Statement on Safe Staffing Levels.

- Van Den Heede K, Bruyneel L, Beeckmans D, Boon N, Bouckaert N, et al. (2020) Safe nurse staffing levels in acute hospitals.

- Abdulai ASB (2024) Nursing Home Staffing Levels and Resident Health Outcomes: Is the Role of the Physical Therapist Undervalued? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 26(2): 105422.

- DeJonghe Y, Ricour C, De Meester C, Malter A, Primus-De Jong C, et al. (2022) An explorative survey to inform staffing policy in nursing homes: a study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Huhta J, Mäntyranta T (2023) Minimum staffing level in 24-hour care for older people to remain unchanged until 1 January 2028. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

- Bae S, Kim H (2020) Level of Resident Care Need and Staffing by Size of Nursing Home under the Public Long-term Care Insurance in South Korea. Journal Of Korean Gerontological Nursing 22(1): 1–9.

- Cermak CA, Bruno F, Jeffs L (2023) Evaluating Skill-Mix Models of Care. JONA The Journal Of Nursing Administration 54(1): 25–34.

- Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation (2023) ANMF position statement – Staffing and standards in home and residential aged care pp. 1–4.

- Department of Health (2024) Framework for safe nurse staffing and skill mix: Phase 3. Government of Ireland.

- Global Nurses United (2025) Global Crisis, Collective Solution: Addressing the Worldwide Nurse Staffing Crisis.

- Griffiths P, Ball J, Drennan J, Dall Ora C, Jones J, et al. (2016) Nurse staffing and patient outcomes: Strengths and limitations of the evidence to inform policy and practice. A review and discussion paper based on evidence reviewed for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Safe Staffing guideline development. International Journal of Nursing Studies 63: 213–225.

- Aiken LH, et al. (2002) Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction, JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 288(16): 1987-1993.

- Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, Van Den Heede K, Sermeus W (2012) Nurses’ reports of working conditions and hospital quality of care in 12 countries in Europe. International Journal of Nursing Studies 50(2): 143–153.

- Aiken LH, Sloane D, Griffiths P, Rafferty AM, Bruyneel L, et al. (2016) Nursing skill mix in European hospitals: cross-sectional study of the association with mortality, patient ratings, and quality of care. BMJ Quality & Safety 26(7): 559–568.

- Auditor General of Alberta 2014, Health and Alberta Health Services - Seniors Care in Long-term Care Facilities Follow-up, Auditor General of Alberta, Canada.

- Bartmess M, Myers CR, Thomas SP (2021) Nurse staffing legislation: Empirical evidence and policy analysis. Nursing Forum 56(3): 660–675.

- Boal AS, Silas L (2015) Canadian Nurses Association, & Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions. (z.d.). Evidence-based Safe Nurse Staffing Toolkit. In Evidence-based Safe Nurse Staffing Toolkit pp. 3–58.

- British Columbia Ministry of Health (2017) Residential Care Staffing Review, British Columbia Ministry of Health, Canada.

- Fajarini M, Setiawan A, Sung C, Chen R, Liu D, et al. (2024) Effects of advanced practice nurses on health-care costs, quality of care, and patient well-being: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Nursing Studies 162: 104953.

- Fernández-García E (2021) Adecuación de la ratio paciente-enfermera y complejidad de los cuidados: un reto para las organizaciones sanitarias. Enfermería Clínica 31(6): 331–333.

- Griffiths P, Saville C, Ball J, Jones J, Pattison N, et al. (2019) Nursing workload, nurse staffing methodologies and tools: A systematic scoping review and discussion. International Journal of Nursing Studies 103: 103487.

- Griffiths P, Saville C, Ball J, Dall Ora C., Meredith P, et al. (2023) Costs and cost-effectiveness of improved nurse staffing levels and skill mix in acute hospitals: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 147:104601.

- Htay M, Whitehead, D (2021) The effectiveness of the role of advanced nurse practitioners compared to physician-led or usual care: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances 3: 100034.

- Kwon H, Kim J (2024) A comparative analysis of nurses’ reported number of patients and perceived appropriate number of patients in integrated nursing care services. Nursing And Health Sciences 26(3).

- Nurse Staffing Levels (Wales) Act 2016.

- Olley R, Edwards I, Avery M, Cooper H (2018) Systematic review of the evidence related to mandated nurse staffing ratios in acute hospitals. Australian Health Review 43(3): 288.

- Queensland Nurses and Midwives’ Union (QNMU) (2018) Ratios Save Lives Phase 2 Extending the care guarantee.

- Registered Nurses' Association of Ontario (2018) Transforming long-term care to keep residents healthy and safe.

- Roberts A (2023) The states with Nurse-Patient Ratio laws | NurseJournal.org. NurseJournal.org.

- Rothgang H, Wagner C (2019) Quantifizierung der Personalverbesserungen in der stationären Pflege im Zusammenhang mit der Umsetzung des Zweiten Pflegestärkungsgesetzes. Bundesministerium für Gesundheit.

- Royal College of Nursing (2023) Impact of Staffing Levels on Safe and Effective Patient Care.

- Royal College of Nursing (2024) The nursing workforce in Scotland.

- Shin S, Park JD, Shin JH (2020) Improvement Plan of Nurse Staffing Standards in Korea. Asian Nursing Research 14(2): 57–65.

- Song Y, Anderson RA, Corazzini KN, Wu B (2014) Staff characteristics and care in Chinese nursing homes: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Nursing Sciences 1(4): 423–436.

- Tait D, Davis D, Roche MA, Paterson C (2024) Nurse/midwife-to-patient ratios: A scoping review. Contemporary Nurse 60(3): 257–269.

- WHO (2010) Code on Ethical Recruitment of Health Personnel.

- Ying L, Fitzpatrick JM, Philippou J, Huang W, Rafferty AM (2020) The organisational context of nursing practice in hospitals in China and its relationship with quality of care, and patient and nurse outcomes: A mixed‐methods review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 30(1-2): 3-27.

- Zaranko B, Sanford NJ, Kelly E, et al. (2023) Nurse staffing and inpatient mortality in the English National Health Service: a retrospective longitudinal study. BMJ Quality & Safety 32: 254-263.

-

Paul De Raeve*, Hannes Vanpoecke*, Manuel Ballotta, Andreas Xyrichis, Yannai DeJonghe and Ivana Žilić*.Strengthening Healthcare through Safe Staffing Levels: A European Policy Perspective on Safe Nurse-to- Patient Ratios and Workforce Sustainability. Iris J of Nur & Car. 5(4): 2025. IJNC.MS.ID.000616.

-

Safe staffing levels, Nurse-to-patient ratios, Nursing legislation, Health workforce governance, Skill mix, National nursing associations, Healthcare policy, EFN survey, Patient safety, Comparative policy analysis

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.