Research Article

Research Article

Integrating Nurses into Cybersecurity Governance: Assessing Preparedness in European Healthcare Systems

Paul De Raeve1*, Manuel Ballotta2, Andreas Xyrichis3 and Ivana Žilić4

1EFN Secretary General at the European Federation of Nurses Associations, Belgium

2EFN Policy Advisor at the European Federation of Nurses Associations, Belgium

3Reader at King’s College London, United Kingdom

4PhD Candidate in Nursing Care, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Maribor, Slovenia

Paul De Raeve, EFN Secretary General at the European Federation of Nurses Associations, Belgium

Received Date:June 10, 2025; Published Date:June 11, 2025

Introduction: The digitalization of healthcare systems across the European Union brings significant benefits in care delivery but also increases the vulnerability of healthcare institutions to cyberattacks. Although national cybersecurity strategies exist, the role of nurses, key actors in care continuity, is often overlooked in these plans and related training programs.

Aim: This study investigates the extent of nurses’ involvement in national and regional cybersecurity plans within the EU, as well as the

availability of cybersecurity education and training specifically for nurses.

Methods: Data from a 2025 survey conducted by the European Federation of Nurses Associations (EFN), covering 20 countries, were analysed

alongside a comparative bibliographic review of 31 National Cybersecurity Strategies (NCS) from EU and associated countries. The study combined

quantitative survey analysis with thematic document review.

Results: Most countries have adopted national cybersecurity plans, but implementation at regional and local levels remains inconsistent. Only

25% of countries involve nurses in cybersecurity planning, and just 20% provide structured training. Nursing staff are rarely mentioned in national

strategies, and clear continuity plans (“Plan B”) for healthcare delivery during cyber incidents are largely absent.

Conclusion: Integrating nurses into cybersecurity governance is critical for strengthening healthcare resilience and patient safety. The study

recommends formal inclusion of nurses in cybersecurity planning, development of targeted educational programs, and EU-funded initiatives to

enhance preparedness for cyber crises. Such measures would improve coordination between digital security and clinical practice.

Keywords: Nurses’ engagement; Cybersecurity governance; Policy co-creation; Healthcare resilience; EU health systems

Introduction

The growing interdependence between digital technologies and healthcare systems has transformed hospitals and healthcare providers into critical nodes within the European Union’s cybersecurity landscape. Digitalisation has enabled wide-scale deployment of electronic health records, AI-supported diagnostics, connected medical devices, and cloud-based data platforms. These technologies significantly improve healthcare delivery, but they also expose the sector to complex cyber risks and operational vulnerabilities [1-4].

In recent years, cyberattacks targeting healthcare systems across the EU have escalated rapidly. Ransomware, phishing, distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, and data breaches now threaten institutional continuity, patient safety, and data integrity. According to the European Commission’s Cybersecurity Action Plan for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers, healthcare has become the most frequently attacked sector in the EU, with ransomware accounting for over half of all major cyber incidents since 2020 [3]. ENISA reports that more than 215 significant incidents have been recorded across Europe’s healthcare sector between 2021 and 2023 alone, revealing the vulnerability of outdated IT infrastructure, fragmented governance, and insufficient cybersecurity training [5,6].

Notable incidents such as the 2021 ransomware attack on Ireland’s Health Service Executive (HSE), the attack on CHU Rouen in France, and the breach of Düsseldorf University Hospital in Germany illustrate the devastating real-world impacts of digital insecurity on care delivery [7,8]. These attacks resulted in largescale service disruptions, cancelled procedures, and exposed patient dana, demonstrating how digital threats quickly become clinical threats.

Despite these risks, national cybersecurity strategies often fail to meaningfully address the healthcare sector, and when they do, frontline health professionals, especially nurses, remain largely excluded. Nurses are the largest professional group in the European health workforce and play a pivotal role in maintaining patient safety, continuity of care, and operational workflows, particularly during system failures [9,10] (Billingsley & McKee, 2016). Yet, they are rarely considered in cybersecurity policy design, emergency simulations, or institutional risk assessments [11,12].

This policy blind spot undermines the EU’s ambition for a resilient digital health infrastructure. Research shows that many nurses lack even basic cyber hygiene training, and few have access to protocols or guidance for responding to cyber incidents, leaving them unsupported and legally exposed during outages or attacks [7,11,13]. Despite their frontline exposure, nurses are treated as passive end-users rather than active agents of digital resilience.

To address this gap, the European Federation of Nurses (EFN) has called for the integration of nurses into cybersecurity governance. In its 2025 policy statement and survey report, EFN advocates for national strategies to recognise the operational and policy contributions of nurses in safeguarding healthcare infrastructure [4,14] (EUSurvey, 2025). The Federation urges stronger collaboration between cybersecurity agencies and nursing organisations, capacity-building through nursing education, and the inclusion of nurses in simulation and preparedness planning.

These calls align with emerging research in the cybersecurity community promoting “human-centric” approaches that incorporate the behavioural, ethical, and organisational dimensions of digital security in healthcare [15-17]. Studies from projects such as PANACEA and EU-CIP reveal the widespread disconnect between cybersecurity frameworks and clinical workflows, especially in Southern and Eastern Europe [18] (Muzhanova et al., 2024).

The 2025 Action Plan by the European Commission proposes several key reforms, including the creation of a Cybersecurity Support Centre for Healthcare under ENISA, targeted funding for smaller providers, and the development of training resources by 2026 [3]. Yet, these measures still fall short in recognising the strategic role of nurses in ensuring patient safety during digital crises.

This article addresses that gap by analysing how the role of nurses is represented, or omitted, in the National Cybersecurity Strategies (NCSS) of EU Member States and associated countries. Through a structured review of NCSS documents and EFN’s 2025 data, this paper maps current practices, identifies strategic shortcomings, and highlights opportunities for more inclusive governance. Embedding nursing expertise in digital health resilience is not only a policy imperative, it is a prerequisite for protecting patient lives in an increasingly digitised care environment.

Study aims and scope

This article investigates how nurses are represented in the context of cybersecurity within national policy frameworks. It is based on a document analysis of the most recent National Cybersecurity Strategies (NCSS) available for selected EU Member States and associated countries.

The study also draws on complementary data gathered through EFN’s 2025 policy activities, including an EU-wide survey and national reports contributed by nursing associations.

The analysis focuses on:

• Whether and how the healthcare sector is addressed in

NCSS

• The degree of recognition of nurses as stakeholders in

cybersecurity

• The availability of cybersecurity-related education and

training for nurses

• And the presence of institutional or legal frameworks

supporting workforce preparedness

The aim is to inform future EU-level policy and funding initiatives, particularly in relation to the 2025 Cybersecurity Action Plan, by highlighting critical gaps and opportunities for integrating nurses into cybersecurity governance.

Methods

Study design

This study employs a combined methodological approach, integrating a quantitative cross-sectional survey with a systematic document analysis. The objective is to investigate nurse involvement in cybersecurity governance within European healthcare systems by assessing national strategies, workforce engagement, training availability, and supporting policies.

Quantitative survey

A structured online survey was developed by the European

Federation of Nurses Associations (EFN) and distributed to 35

National Nurses’ Associations (NNAs) across Europe in early 2025.

The survey contained questions addressing:

• The existence of cybersecurity plans at national, regional,

and hospital levels

• Nurse involvement in policy development and

implementation

• Availability and formats of continuing professional

development (CPD) related to cybersecurity for nurses

• Legal or institutional obligations for training provision

The survey also included a limited number of open-ended questions to capture examples of good practice and challenges. Twenty complete responses were analysed using descriptive statistics for quantitative data and thematic coding for textual responses.

Systematic document analysis

A systematic content analysis was conducted on 31 publicly

available National Cybersecurity Strategies (NCSS) from selected

European countries, identified via the ENISA NCSS Interactive Map.

Documents were examined for:

• Recognition of healthcare as critical infrastructure

• Explicit references to nurses or nursing staff

• Provisions for healthcare personnel training in

cybersecurity

• Publication year

• Inclusion of operational continuity plans (“Plan B”)

This structured analysis facilitated cross-country comparison of policy focus, gaps, and exemplary approaches.

Findings from both data sources were combined to provide a comprehensive overview of nurse involvement in cybersecurity governance.

Ethical considerations

This research did not involve the collection or analysis of individual-level health data or any personal identifiers. All data were obtained from officially recognised professional nursing associations acting as representatives of their national constituencies. The study protocol underwent internal review and approval by the executive leadership of the European Federation of Nurses Associations (EFN). All participants received clear information regarding the study’s purpose, scope, and data usage, ensuring transparency and voluntary participation.

Limitations

This study has several important limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the data were collected through self-reporting by national nursing associations, which may reflect organisational knowledge and perspectives rather than comprehensive or system-wide evidence. This may introduce a bias, as the responses represent the views of professional bodies rather than all stakeholders involved in cybersecurity governance within healthcare systems.

Second, there is variability in how key terms such as “cybersecurity plan” or “mandatory training” are understood and implemented across different countries. This lack of standardisation can affect the comparability of data and may obscure nuanced differences between national strategies and practices.

Third, while the survey achieved responses from twenty countries, several EU Member States and associated countries were not represented. This incomplete geographic coverage limits the generalisability of the results to the entire European region.

The study did not include corroborating data from other relevant stakeholders such as ministries of health, IT departments, or hospital administrators. The absence of such triangulation restricts the ability to cross-validate findings and to build a more holistic understanding of cybersecurity governance in healthcare.

Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable insights into patterns of nurse involvement, preparedness, and policy fragmentation across Europe. These insights provide a solid foundation for informing policy discussions and identifying priorities for future research.

Results

From the 35 National Nurses’ Associations (NNAs) contacted within the EFN network, 20 completed the survey fully and provided data suitable for analysis. These responses represent a wide geographic and health system diversity, covering countries from Northern, Southern, Eastern, and Western Europe, as well as EU and non-EU members. Countries included are Ireland, Estonia, Germany, Netherlands, Denmark, Iceland, Austria, Norway, Portugal, Switzerland, Czech Republic, Sweden, Italy, Malta, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Spain, France, Belgium, and Poland.

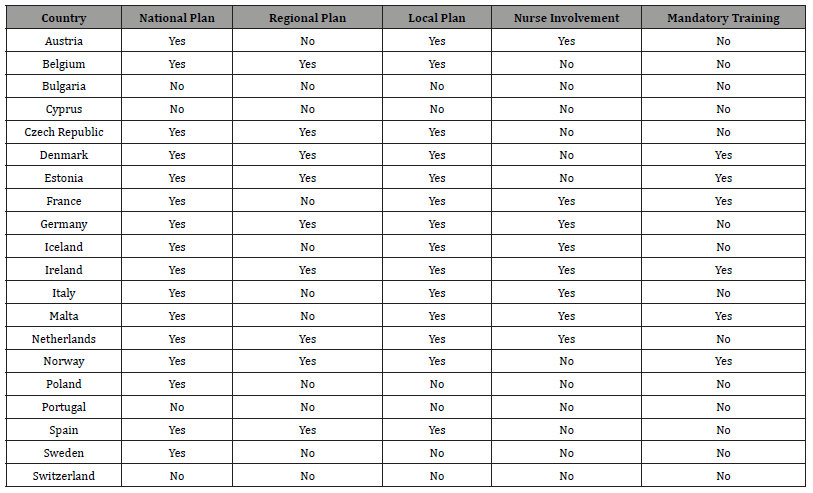

The survey captured multiple dimensions of cybersecurity preparedness, nurse involvement, and training availability, allowing a comprehensive cross-national comparison (see Table 1).

Table 1:Detailed EFN survey responses by country.

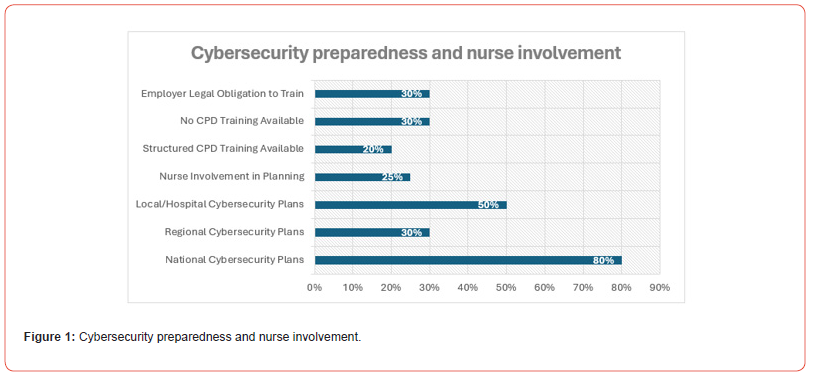

Presence of cybersecurity strategies

Among the 20 countries surveyed, 16 (80%) confirmed the existence of a national cybersecurity strategy or equivalent legal framework covering the healthcare sector. However, the adoption of cybersecurity strategies at regional and local (hospital) levels was markedly less consistent, with only 6 (30%) and 10 (50%) countries respectively reporting such plans (Figure 1).

Notably, countries with decentralized health systems, such as Germany and Denmark, more frequently reported regional strategies, but even here the legal binding nature and visibility of these strategies varied. At the hospital level, some countries like Iceland and Estonia demonstrated strong leadership, with Iceland’s Landspitali hospital developing a nurse-led cybersecurity plan and Estonia mandating national digital security standards across all healthcare institutions.

Conversely, countries such as Portugal, Cyprus, Bulgaria, and Switzerland reported little or no formal cybersecurity planning at sub-national levels, indicating potential vulnerabilities in operational readiness.

A striking finding was the low degree of formal nurse involvement in cybersecurity governance. Only 5 of the 20 countries (25%) reported structured or formal participation of nurses in cybersecurity planning processes. Examples include Iceland, where nurses authored the hospital cybersecurity plan; Austria and Malta, where nurses participate in working groups or reporting mechanisms; and Germany and the Netherlands, where involvement tends to be informal and limited to nurses with additional informatics or managerial roles.

The remaining 75% of countries either reported no nurse involvement or only informal and situational consultation, with cybersecurity governance largely led by IT or administrative departments. This siloing between clinical staff and cybersecurity decision-making poses risks to operational resilience, given the frontline role nurses play during cyber incidents.

Regarding education and training, only 4 countries (20%) provide structured and mandatory cybersecurity training for nurses. Ireland, for example, introduced mandatory training after the 2021 HSE cyberattack, while Norway and Denmark require e-learning or participation in national awareness campaigns. Half of the countries offer training sporadically at institutional levels, with formats ranging from voluntary e-learning modules to post-incident briefings. The remaining 30% reported no cybersecurity training opportunities for nursing staff, often perceiving cybersecurity as outside the clinical scope.

Legal obligations mandating employers to provide cybersecurity training exist in only 6 countries (30%), commonly embedded within broader national digital health strategies, GDPR policies, or occupational safety regulations. Many countries lack explicit legal frameworks, resulting in uneven and often voluntary training availability.

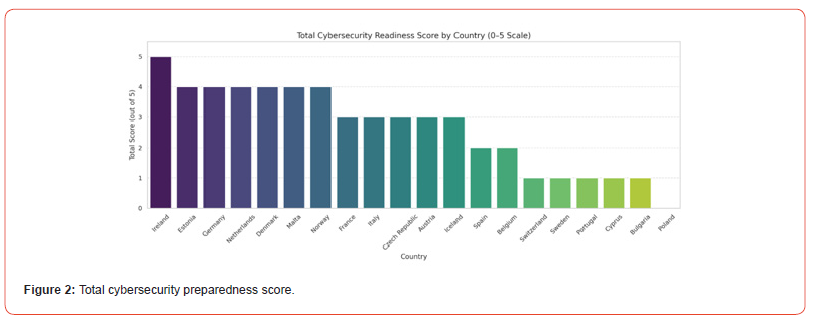

Total cybersecurity preparedness score

To provide a comparative snapshot, countries were scored on five indicators: presence of national, regional, local plans, nurse involvement, and mandatory training, yielding a maximum score of 5. Ireland achieved the highest score of 5, reflecting comprehensive national planning, nurse engagement, and mandatory training. Estonia, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, and Malta followed closely with scores of 4.

At the lower end, countries such as Cyprus, Bulgaria, and Poland scored 0 or 1, indicating substantial gaps in cybersecurity preparedness and nurse inclusion. This scoring highlights the disparity in readiness across Europe and underscores the uneven integration of frontline nursing staff in cybersecurity governance (see Figure 2).

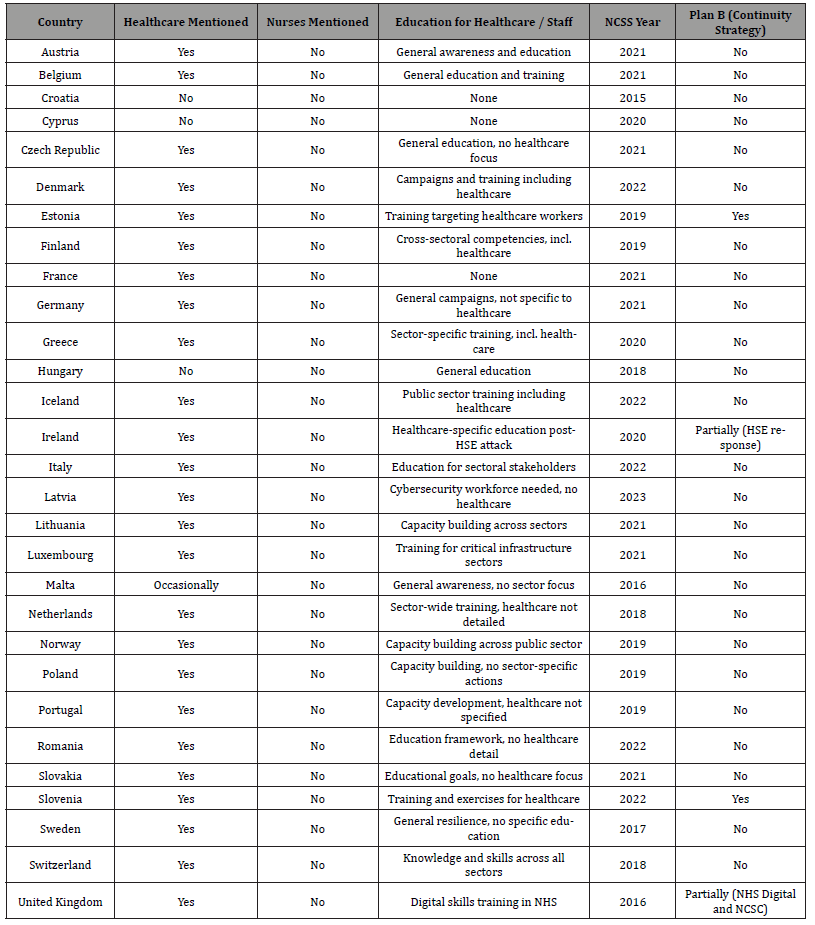

Bibliographic analysis of national cybersecurity strategies (NCSS)

The review of 31 NCSS documents showed that healthcare is widely recognised as critical infrastructure in 26 countries. Yet, none explicitly mention nurses, reflecting a major oversight given nurses’ frontline role in patient care continuity during cyber incidents.

Education or training initiatives specific to healthcare personnel appear in only a few countries, notably Estonia, Slovenia, and Ireland. Operational continuity plans, or “Plan B” strategies, designed to maintain healthcare services amid cyber disruptions, are found only in Estonia, Slovenia, and the UK.

Many strategies date from 2015 to 2023, with most updated within the last five years, but a systemic lack of nursing representation and sector-specific resilience planning persists. This gap between policy rhetoric and operational integration represents a critical challenge for Europe’s cyber health security (see Table 2).

Table 2:National cybersecurity strategies.

Discussion

The findings from the EFN survey and the analysis of National Cybersecurity Strategies (NCSS) reveal a significant and persistent gap between European cybersecurity policy frameworks and their practical application within healthcare systems. While most EU Member States have adopted national cybersecurity plans recognizing healthcare as critical infrastructure [19,20], this recognition rarely translates into concrete operational strategies at regional, local, and clinical levels. The EFN survey found that only 35% of countries reported regional cybersecurity plans, and merely 50% indicated the existence of hospital-level protocols, reflecting the fragmented nature of cyber resilience within health services [4,20].

This gap between policy and practice poses serious risks. Frontline healthcare workers, especially nurses, play a pivotal role in maintaining care continuity during cyber incidents. Nurses operate at the intersection of digital systems and patient care, often required to improvise workflows and revert to manual processes when technology fails [9,10]. Yet, despite their central role, nurses remain largely excluded from cybersecurity planning, training, and governance. Only 25% of surveyed countries involve nurses formally in cybersecurity planning, and structured training targeted specifically at nurses exists in only 20% of the cases [4,11].

The bibliographic analysis of 31 NCSS documents confirms this exclusion at a strategic level: while healthcare is almost universally mentioned as critical, none explicitly recognize nurses or nursing staff as integral to cybersecurity preparedness or response [14,19]. Only a handful of countries, such as Estonia, Ireland, and Slovenia, include provisions for healthcare staff training or continuity planning, and even these lack explicit inclusion of nurses (Muzhanova et al., 2024) [20]. This omission represents a missed opportunity to leverage the largest and most patient-facing health workforce for digital resilience.

Real-world case studies highlight the consequences of this oversight. The 2021 ransomware attack on Ireland’s Health Service Executive disrupted acute care services extensively. Nurses were essential in developing and executing manual workaround procedures, from paper documentation to medication tracking, ensuring patient care continuity despite system failures [14]. However, these efforts were often ad hoc and unsupported by formal training or institutional protocols, underscoring the need for systematic inclusion of nurses in cybersecurity preparedness.

Beyond operational considerations, this exclusion reflects a deeper structural challenge. Cybersecurity in healthcare is frequently conceptualized as a technical issue managed by IT departments and external consultants, marginalizing clinical staff and underestimating the complexity of clinical workflows [21]. The concept of “human-centric” cybersecurity, advocated by Salminen & Hossain [15] and Zojer [16], stresses the integration of behavioural, social, and ethical dimensions into cyber resilience strategies, with nurses positioned as key stakeholders due to their frontline roles and holistic understanding of care systems.

The European Federation of Nurses (EFN) has been at the forefront of advocating for the formal recognition of nurses in cybersecurity governance. EFN’s 2025 reports and policy statements emphasize the necessity of tailored capacity building, interdisciplinary collaboration, and empowering nurses as active contributors to digital resilience [4,14]. These calls align with the European Commission’s Cybersecurity Action Plan for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers [6], which introduces a Cybersecurity Support Centre for Healthcare and funding for capacity building but stops short of explicitly including nurses as central actors [3].

Effective cybersecurity preparedness requires robust education and training programs for healthcare professionals, particularly nurses. The survey revealed that where training exists, it is often generic, IT-led, and disconnected from clinical realities, limiting its impact [17]. The WHO’s Health Workforce Resilience framework similarly identifies inadequate digital skills training as a barrier to frontline readiness and recommends embedding cybersecurity competencies within pre-licensure and continuing professional development (CPD) curricula [22].

Some countries have made strides in integrating nurses into cyber preparedness activities. For example, Estonia’s national campaign “Cyber Hygiene for Health Professionals” mandates role-specific training for nurses and includes them in incident response plans (Muzhanova et al., 2024). Denmark’s Region Midtjylland involves nurses in live cyber simulations, resulting in improved coordination and patient-centred crisis management [23]. However, such examples remain the exception rather than the rule, with many regions, especially in Southern and Eastern Europe, relying on voluntary or ad hoc training initiatives [4].

Economic analyses also support investing in nurse-inclusive cybersecurity strategies. Cyberattacks cause substantial financial losses due to operational disruptions, delayed care, and increased administrative burden. Nurses’ ability to rapidly adapt workflows and implement fallback procedures mitigates these costs [24]. Pears & Konstantinidis [17] demonstrate through economic modelling that integrated training and preparedness can reduce recovery time by up to 50%, lowering both direct and indirect costs associated with cyber incidents.

The institutional silos separating IT and clinical functions hinder the development of resilient health systems. Closing this gap demands stronger collaboration between nursing organisations, cybersecurity agencies, and policymakers. Nurse associations’ political visibility and legal frameworks enabling their engagement in digital health governance vary across Member States, influencing their capacity to shape policy [25,26]. Enhanced inclusion mechanisms, potentially through the European Health Data Space (EHDS) and the NIS2 Directive, could standardize nurse involvement across the EU [3].

Cybersecurity in healthcare must evolve from a technical challenge into an integrated organisational responsibility. Nurses, as the backbone of patient care, must be empowered through formal inclusion in governance, tailored education, and operational planning. Developing a nurse-informed “Plan B” for cyber crises, encompassing preparedness standards, fallback drills, and ethical protocols, is imperative for safeguarding patient safety and healthcare system resilience. The European Commission’s forthcoming actions and EFN’s advocacy provide a timely foundation for this transition, promising a more secure, resilient, and patient-centred digital health future for Europe.

To close this gap, the EU must move toward a clericalized model of cybersecurity preparedness. A dedicated “Plan B” framework, codeveloped with nurses and other frontline actors, could transform digital risk governance in healthcare.

Such a plan should include:

• Minimum preparedness standards for hospitals and

community care

• Mandatory fallback drills involving all staff, not just IT

• Integrated CPD programs with case-based cyber failure

scenarios

• Clear ethical protocols for clinical decision-making during

outages

This would bring digital preparedness in line with the ethical, operational, and organisational standards demanded by modern care environments. It would also fulfil the objectives of ENISA’s 2025 Cybersecurity Action Plan and the WHO’s global recommendations.

Ultimately, the survey’s findings reinforce a simple reality: cybersecurity cannot remain the domain of IT departments alone. It must become an integrated organisational function, embedded in the culture, practice, and education of all healthcare workers. Nurses, given their scope of responsibility and digital exposure, are essential to this transition.

Policy Implications and Conclusion

The findings of this study underscore a critical reality: policy mandates alone are insufficient to achieve robust cybersecurity resilience in European healthcare systems. Without the embedded participation of clinical staff, particularly nurses, cybersecurity policies risk remaining theoretical frameworks, detached from the operational realities they intend to safeguard.

Professional nursing organizations, such as the European Federation of Nurses Associations (EFN), hold a unique intermediary position between high-level policymakers and frontline healthcare workers. EFN has consistently advocated for the integration of digital competencies into nursing continuing professional development (CPD) and for a formal role of nurses in shaping health security strategies [4,14]. However, as highlighted by Arabi et al. [25], nurses’ capacity to influence policy is closely linked to their political visibility and the governance frameworks within healthcare systems. Member States with strong nursing unions and well-established regulatory bodies, like Finland and Sweden, demonstrate greater nursing participation in digital health policymaking compared to countries were nursing lacks formal political representation.

Excluding nurses from cybersecurity preparedness not only compromises operational efficiency but also generates significant economic costs. Cyberattacks impose direct financial burdens, including system recovery expenses and regulatory penalties, alongside indirect losses due to cancelled procedures, delayed diagnoses, and increased staff burnout. Studies from the UK and Germany estimate that each hour of digital downtime costs hospitals between €40,000 and €90,000, with nurses playing a central role in mitigating these costs through workflow adaptation and manual processes [24]. Economic modelling indicates that investing in structured training, fallback drills, and inclusive planning can reduce mean recovery time by 35–50% in large hospital systems, significantly lowering post-incident costs [17].

Simulation-based preparedness has emerged as a gold standard for building resilience. While ENISA’s biennial “Cyber Europe” exercises involve broad governmental and IT sector participation, the clinical workforce, especially nurses, remains underrepresented. Evidence from Denmark’s Region Midtjylland demonstrates that including nurses in live cyber simulations enhances institutional coordination, accelerates recovery, and fosters more patient-centred responses during crises [23]. Scaling such initiatives EU-wide necessitates dedicated funding and legal mandates but promises substantial improvements in healthcare cybersecurity resilience.

The EFN survey indicates that European healthcare cybersecurity is at a critical juncture. Policy frameworks and technological investments continue to evolve, yet they remain fragile without grounding in clinical practice and workforce realities. Nurses are the connective tissue between digital systems and patient care. Their meaningful inclusion in policy development, training programs, and operational governance is essential to achieving sustainable digital health resilience.

Urgent structural reforms are required to reposition cybersecurity as a shared clinical responsibility. A nurse-informed “Plan B” framework should include minimum preparedness standards, mandatory fallback drills involving all clinical staff, integrated CPD programs featuring realistic cyber failure scenarios, and clear ethical protocols guiding clinical decision-making during digital disruptions. Such measures would align cybersecurity with the ethical, operational, and organizational demands of modern healthcare, fulfilling objectives outlined in the ENISA 2025 Cybersecurity Action Plan and the WHO’s Health Workforce Resilience framework.

To ensure that nurses are not merely passive technology users

but active resilience partners, the European Commission should

consider the following policy actions:

1) Amend implementation guidelines under the NIS2

Directive to mandate structured involvement of frontline

clinical professionals, starting with nurses, in cybersecurity

governance.

2) Require Member States to designate nursing

representatives in hospital and regional digital crisis

management teams.

3) Link eligibility for EU funding (e.g., Digital Europe,

Recovery and Resilience Facility, Horizon Europe) to nurse-led

cybersecurity simulations and fallback preparedness activities.

4) Establish an EU-funded “Plan B” contingency framework

co-developed with frontline healthcare workers, including

templates for manual workflows, role-shift protocols during

digital collapse, and sector-specific fallback playbooks hosted

by ENISA.

5) Declare cybersecurity CPD for health professionals a

legal right and employer obligation, supported by a verifiable

European Cybersecurity Passport system.

6) Prioritize targeted support and capacity-building for

Member States with low readiness scores, ensuring solidarity

based on need.

7) Promote nurses’ engagement and co-creation in the digital

health transition by ensuring their inclusion in governance

structures, providing funding for nursing involvement in digital

transformation programs, and supporting research into nursedriven

cybersecurity innovation [27-42].

The exclusion of nurses from cybersecurity governance represents a critical vulnerability in European healthcare systems. This study demonstrates that without their formal inclusion, even the most comprehensive policies will fail in practice. Empowering nurses through structural inclusion, targeted training, and participatory governance is not only a policy imperative but a prerequisite for safeguarding patient safety and healthcare continuity in an increasingly digital future.

Acknowledgment

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Kruse CS, Frederick B, Jacobson T, Monticone DK (2017) Cybersecurity in healthcare: A systematic review of modern threats and trends. Technology and Health Care 25(1): 1-10.

- Kim Lee (2021) Cybersecurity and related challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing 51(2): 17-20.

- European Commission (2025a) Communication on the European Action Plan on the Cybersecurity of Hospitals and Healthcare Providers. COM (2025)10 final. Brussels: European Commission.

- EFN (2025a) EFN Report on EU Cybersecurity – with National Reports. Brussels: European Federation of Nurses.

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) (2023) Threat Landscape for Health Sector – 2023.

- European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) (2025) National Cyber Security Strategies – Interactive Map.

- Kamerer JL, McDermott DS (2023) Cyber hygiene concepts for nursing education. Nurse Education Today 130: 105940.

- Nikbakht Nasrabadi A, Norouzkhani N, Manookian A, Cheraghi MA, Mohammadi M, et al. (2024) Safeguarding Patient Information as an Issue Faced by Nurses: A policy brief. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management 19(2).

- Avci DIA (2020) The Integral Role of Nurses in Healthcare Transformation; Leading Change and Innovation. Asia Pacific Journal of Nursing Research 1(1): 1-3.

- Živanović D, Javorac J, Dimoski Z, Šumonja S (2021) Profesija sestrinstva u savremenom sistemu zdravstvene zaštite i javnom zdravlju - nove uloge i izazovi. Zdravstvena zaštita 50(2): 73-86.

- Rajamäki J, Rathod P, Kioskli K (2023) Demand Analysis of the Cybersecurity Knowledge Areas and Skills for the Nurses: Preliminary Findings. European Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security. Proceedings of the 22nd European Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security 22: 1.

- Nahm Eun-Shim, Poe Stephanie, Lacey Darren, Lardner Michelle, Van De Castle, et al. (2019) Cybersecurity Essentials for Nursing Informaticists. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing 37(8): 389-393.

- Oducado RMF, Dinero EMG, Fuentes IKM, De la Peña JFL, Ermita GB (2022) Cybersecurity skills of Filipino nursing students at a public tertiary institution. WVSU Research Journal 11(2): 1–7.

- EFN (2025b) EFN Policy Statement on Cybersecurity in Healthcare. Brussels: European Federation of Nurses.

- Salminen M, Hossain K (2018) Digitalisation and human security dimensions in cybersecurity: an appraisal for the European High North. Polar Record 54(2): 108-118.

- Zojer G (2020) Moving the human being into the focus of cybersecurity. In: M Salminen, G Zojer, K Hossain, (eds.) Digitalisation and Human Security. New Security Challenges. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan pp. 353–363.

- Pears M, Konstantinidis S (2021) Cybersecurity Training in the Healthcare Workforce – Utilization of the ADDIE Model. 2021 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) pp. 1674–1681.

- Kalliopi Anastasopoulou, Pasquale Mari, Aimilia Magkanaraki, Emmanouil G Spanakis, Matteo Merialdo, et all. (2020) Public and private healthcare organisations: a socio-technical model for identifying cybersecurity aspects. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance (ICEGOV '20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, pp. 168–175.

- European Commission (2023) Cybersecurity in the health sector: Increasing resilience in critical infrastructures.

- ENISA (2022) ENISA Threat Landscape for the Healthcare Sector – 2022. European Union Agency for Cybersecurity.

- Christou G (2017) The EU’s approach to cybersecurity. European Security 26(1): 126–144.

- WHO (2021) Health Workforce Resilience during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Review and Policy Recommendations. World Health Organization.

- Skias S, Tsekeridou S, Polemi N (2022) Demonstration of alignment of the Pan-European cyber incident response framework with healthcare sector resilience. Journal of Information Security and Applications 67: 103165.

- Biasin E (2020) Healthcare Critical Infrastructures Protection and Cybersecurity in the EU: Regulatory Challenges and Opportunities. SSRN Electronic Journal [online].

- Arabi, Akram, Forough Rafii, Mohammad Ali Cheraghi and Shahrzad Ghiyasvandian. “Nurses’ policy influence: A concept analysis.” Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 19 (2014): 315 - 322.

- Zalon Margarete L, Ludwick Ruth, Patton Rebecca (2024) Strengthening Nurses' Influence in Health Policy. AJN, American Journal of Nursing 124(9): 28-36.

- Al Harthi, M, Al Thobaity A, Al Ahmari M, Alotaibi R (2021) Nurses’ disaster preparedness: A systematic review. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 15(4): 486–494.

- Albert D, Walton S (2020) Voice of the Nurse. In: Sreeramoju P, Weber S, Snyder A, Kirk L, Reed W, Hardy-Decuir B (eds) The Patient and Health Care System: Perspectives on High-Quality Care. Springer, Cham.

- Fraher EP, Spetz J, Naylor MD (2015) Nursing in a Transformed Health Care System: New Roles, New Rules.

- Hollnagel E, Braithwaite J, Wears RL (2015) Resilient Health Care, Volume 2: The Resilience of Everyday Clinical Work. CRC Press.

- McBride M, Kilgore C, Gunowa, NO (2024) The role of community and district nurses. Clinics in Integrated Care 27: 100231.

- O’Reilly M, Dempsey M, Gleeson A (2022) Understanding frontline healthcare workers’ experiences during the HSE ransomware cyberattack: A qualitative study. BMJ Health & Care Informatics 29(1): e100538.

- OECD (2022) Strengthening health system resilience through digital health. OECD Health Working Papers No. 139. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Perla Lisa (2002) The Future Roles of Nurses. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development (JNSD) 18(4): 194-197.

- Pirinen R, Ratho, P, Gugliandolo E, Fleming K, Polemi N (2024) Towards the Harmonisation of Cybersecurity Education and Training in the European Union Through Innovation Projects. 2024 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON).

- Polemi N, Kioskli K (2023) Enhancing Practical Cybersecurity Skills: The ECSF and the CyberSecPro European Efforts. Human Factors in Cybersecurity.

- Rushton CH, Schoonover-Shoffner K, Kennedy MS (2019) Executive summary: Transforming moral distress into moral resilience in nursing. The American Journal of Nursing 119(2): 52–56.

- Smith EL, et al. (2016) Cybersecurity in the Clinical Setting: Nurses’ Role in the Expanding Internet of Things’, The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing. SLACK Incorporated 47(8): 347–349.

- Spanou I (2024) The EU Cybersecurity Skills Academy: A silver bullet to the skills gap? Cybersecurity in Europe Policy Brief Series.

- Taft SH, Nanna KM (2008) What Are the Sources of Health Policy That Influence Nursing Practice? Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice 9(4): 274-287.

- Tasheva Iva (2017) European cybersecurity policy – Trends and prospects. EPC Policy Brief.

- Zvozdetska O (2019) EU Cybersecurity in the Context of Increasing Cyberthreats in the Modern Globalized World. Mediaforum: Analytics, Forecasts, Information Management 7: 27-46.

-

Paul De Raeve*, Manuel Ballotta, Andreas Xyrichis and Ivana Žilić. Integrating Nurses into Cybersecurity Governance: Assessing Preparedness in European Healthcare Systems. Iris J of Nur & Car. 5(3): 2025. IJNC.MS.ID.000615.

-

Nurses’ engagement, Cybersecurity governance, Policy co-creation, Healthcare resilience, EU health systems

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.