Research Article

Research Article

Impact of the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cervical Cancer on the Sexual Health of the Couple

Antonieta Silva M1* and Teresa Urrutia2

1Nurse-Midwife, PhD in Nursing degree, Teacher at Obstetrics and Childcare School, Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile

2Nurse-Midwife, PhD. Research Professor, School of Nursing, Universidad Andres Bello, Chile

Antonieta Silva M, Nurse-Midwife, PhD in Nursing degree, Teacher at Obstetrics and Childcare School, Universidad de Valparaíso, Chile

Received Date:March 12, 2024; Published Date: March 19, 2024

Summary

The efficacy of treatment for cervical uterine cancer (CUca) results in increased survival for women, but with significant side effects that affect the quality of marital sex life. Objective: to explore the evolution and impact of the diagnosis and treatment of the CUca in the couple´s sexual health, from the woman´s point of view. Methodology: qualitative, multicenter, descriptive, and interpretative study in 17 women affected by the disease. Results: 5 dimensions emerge, sexual accompaniment of the couple, contagion, infidelity and promiscuity, desire of not having a partner, to please the partner and infidelity or abandonment by the partner. Women value the effective sexual accompaniment of their partners; they are clear that they have caught the cancer through sexual intercourse, and they are afraid of getting it again. Being alone emerges as an option to be safe and calm. Those who fear infidelity and abandonment, assume dyspareunia despite the lack of desire and sexual enjoyment, even accepting the use of noncoital alternatives to sexually satisfy their partners. Conclusions: The diagnosis and treatment of the CUca impacts the sexual health of the couple that requires advice and support to adapt to the physical and/or emotional changes that the disease entails.

Keywords: Sexual behavior; Uterine Cervical Neoplasms; Sexual health

Introduction

The cervical uterine cancer (CUca) corresponds to 10% of cancers in women worldwide. Although it is a preventable and curable disease, it continues to be a public health issue and a threat to women´s lives [1].

The efficacy of the treatment improves survival by 71%, rising to 92% in early stages [2-5]. After diagnosis and during the treatment, women try to balance the expression of their sexuality in the face of the threat of the disease, trying to maintain intimacy with their partners, despite the physical and psychological deterioration caused by the diagnosis and treatment [6].

The quality of sexuality of women with CUca evolves over time from a physical perspective as a sexual act to a more global and emotional dimension, influenced by a different perspective of life, the support of their sexual partner and the coexistence of side effects of the treatment [7]. The resumption of sexual activity after diagnosis or treatment for CUca is complex mainly due to the presence of physical symptoms, but when communication deficiencies coexist in the couple, it can compromise sexual life and the bond [8].

Al though there is information on the quality of life and sexual function of these relation (is still a lack of knowledge about the impact on the couple´s relationship after the diagnosis and treatment of CUca, in order to establish interventions aimed at reducing the negative consequences in the conjugal relation [9,10].

The objective of the study was to explore the evolution and impact that the diagnosis and treatment of CUca has in the couple´s sexual health, from the woman´s point of view.

Methodology

The research corresponds to a multicenter, descriptive, and interpretative study and under the qualitative paradigm, shaping reality through meanings and interpretations built by the women themselves [11], in relation to the impact that can occur in the sexual sphere of the couple´s relationship, after the transcendent and exceptional event of being diagnosed and treated for CUca. The study was carried out during the months of January and October 2020. It was approved by the ethics committees of Carlos Van Buren and Gustavo Fricke hospitals, both belonging to Valparaíso San Antonio and Viña del Mar Quillota Health Services accordingly. Each interviewee was invited to participate voluntarily after signing an informed consent, safeguarding psychological well-being, privacy, and confidentiality, in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration as revised in 2013 [12].

7 in-depth interviews were conducted, a number that made it possible to reach information saturation [13]. The sample was for convenience. The inclusion criteria included women between 25 and 64 years old, at least six months after being diagnosed and treated for cervical uterine cancer with FIGO staging in stages I and II, with a partner, an active sexual life, and a stable relationship of at least 3 months before being diagnosed.

The interviews had an average duration between 40-60 minutes, were carried out in hospital facilities, were audio recorded and later transcribed in Word. Notes were taken during each interview to strengthen the analysis process [14].

The guiding question of the interview was: How has the couple´s relationship evolved in the sexual sphere after the diagnosis and treatment for CUca?

Data analysis was carried out using a Krippendorf content analysis [13]. The technique in surveying the dimensions and categories required compliance with principles such as: mutual exclusion, homogeneity, relevance, fidelity, and productivity [15,16]. The coding was reviewed according to the characteristics of the relevant experiences shared by the interviewees, in addition to their evolution over time within the CUca context. The analysis was carried out by the two authors of this article.

Results

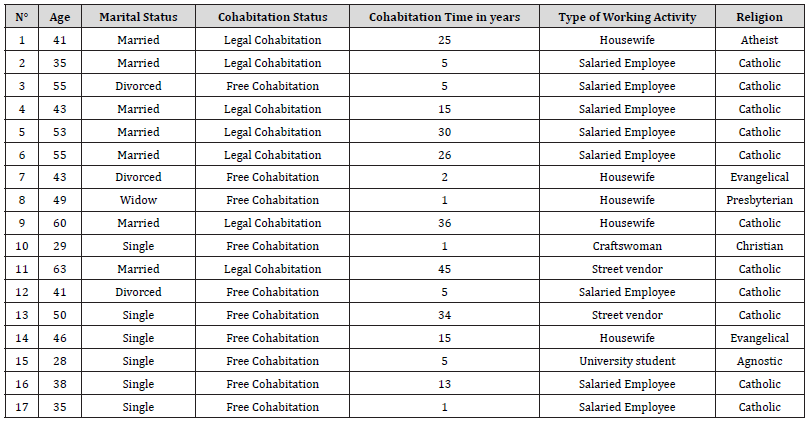

The average age of the women was 45 years old, with a range between 28 and 63 years old. With a predominantly high school and technical school education level, in addition to diverse working activities. Most of them expressed professing the Catholic religion. Seven of the participants maintained a legal cohabitation, while the rest maintained a free cohabitation, all with an average time of duration with the last partner of 16 years (see table 1).

Table 1:Demographic characteristics of the women interviewed.

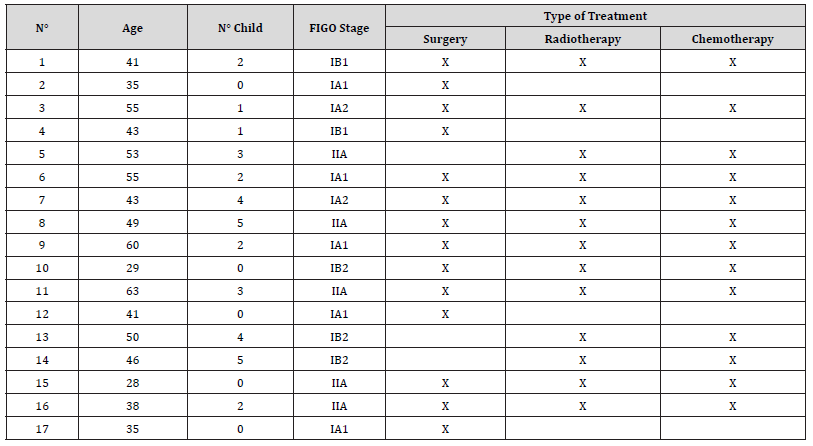

In relation to the biomedical characteristics, (see table 2) 29% of the women (n=5) stated that they did not have children. Regarding the treatment received, it stands out that the highest percentage of them had undergone both surgery and radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Table 2:Biomedical characteristics of the women interviewed.

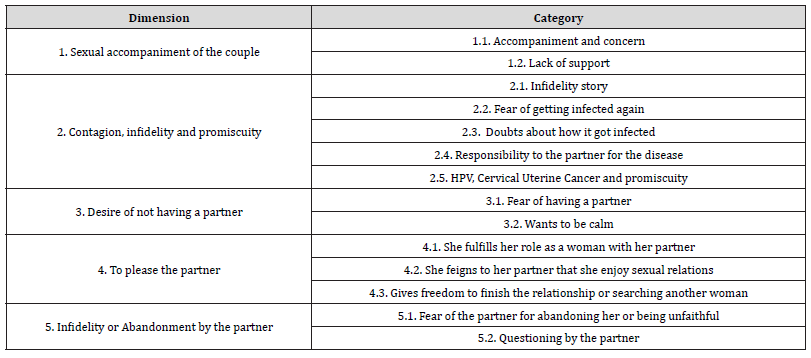

In relation to the evolution of the couple´s relationship, in table 3 we can observe the 5 dimensions and corresponding categories extracted from the 17 interviews. The evolution in the sexual field considered aspects of accompanying the couple during the process experienced, as well as how the history of the couple becomes relevant during this process. The abandonment, the infidelity are aspects that arise in the stories of these women. Sexual pleasure and the ways to achieve it were also a reason for reflection during the interviews.

Table 3:Dimensions and Categories found.

Dimension 1: Sexual accompaniment of the couple

In this dimension, the phenomenon of accompaniment of the couple is revealed in a dual way, on the one hand, there is the recognition that women make in the face of understanding and respect, valuing the affection, concern and not feeling pressured by their partners, and on the other hand are those women who report a lack of support from their partners in the sexual sphere.

Those who experience this period “accompanied” value the respectful attitude of their partners during their disease, feeling loved and trusted, especially when they take the time to accompany them sexually. They value “the patience” of their partners in waiting for them, not pressuring them, giving themselves time and being careful with them in an intimacy that they report as “modified”.

“I greatly appreciate the attitude of my partner throughout this process, because he has been very respectful and collaborative in sexual matters” (VB13)

“Then, the first time that we, that after all this and I was given permission and what to say all, it hurt me, and he told me… I don´t want to hurt you. I never thought that he would be so understanding” (VB3)

Likewise, there are those women who perceive a lack of attention, affection, and sexual support in intimacy from their partners and the feeling of distance from them. They describe a lack of affection, understanding or patience, pointing out the “need” that men have beyond caresses or kisses:

“One can give caresses, kisses, but the man asks for more… From his side there was very few hugs, very few…. That is why I made the decision to separate. It was difficult…, I mean is not a bad man, not a bad father, but not anymore, he changed a lot…things have changed, I´m not saying it was only his fault, because problems are always shared by two, but I was expecting more from my partner, more understanding and there was none” (VB1)

Dimension 2: Contagion, infidelity, and promiscuity

This dimension brings together stories in relation to women´s doubts about how they got cancer. Some are aware of the causal agent and blame their partners for having infected them, which is related to the stories of infidelity and the fear of having a new partner.

Painful stories of infidelities experienced with the partner are revealed and testimonies of physical and/or psychological violence emerge. They are disillusioned, distrustful and assume unlike the men, that as women they idealize the relationship committing themselves emotionally:

“For me it was very shocking to know about my husband´s infidelity, the most painful and complex and above all that he continued doing it during the period of my disease. I felt disappointed as a woman, you feel… The most difficult was to put myself together again after that” (VB9)

Some women are clear that they have acquired CUca through sexual intercourse, so they are afraid of re-infection.

“…and the other thing that I´m also afraid of is that I could get sick with some other disease that may not be the same, but some venereal disease, because with this I have started to study, to read, everything, is like I have my brain full of things. Everywhere I´m seeing that I can get something, it is like something traumatic” (VB 5)

However, some women reveal doubts about how and when they got sick.

“I know that this comes from the human papilloma through sexual intercourse, but I don´t know more than that. I didn´t use condoms because I had a stable partner. Actually, I rarely used condoms with my previous partners, rarely really. I don´t know when I finally got sick, or to whom I got sick, so who I am going to blame at this point” (VB 15).

The association between human papilloma virus with infidelity and dirt appears in some stories, which causes them shame, since others may think that they have had a disorderly and promiscuous sexual life.

“Because it makes me feel a little embarrassed… “The issue of human papilloma is…, it means like dirt, something like… For me it is a topic like promiscuity, dirt and all that. So, saying that I have cervical uterine cancer people may think that I am promiscuous, something like that. Yes, that is what the doctor explained to me, so I think that is. As if I had many partners, a disorderly sexual life and is not like that. I have had a very quiet life, so that makes me feel really bad” (VB 5)

Dimension 3: Desire of not having a partner

The stories of this dimension point out the desire of women to be calm and not be sexually pressured by their partners. There is fear of having sexual relations and maintaining a relationship. They want to be without obligations or dependencies, and even when they want to feel loved and trust again, they don´t feel ready yet.

The stories orient towards the need to be well with themselves first to trust and be loved again. Some of them carry stories of infidelities by their partners, arising the fear of being cheated on again, infected and living the experiences that cancer meant makes them not want to give themselves another chance to be in couple, despite being encouraged by family and friends.

“I need to be well myself in order to be well with somebody else, but I don´t see myself with someone, I don´t see myself in a relationship again” (VB 5)

“Well, when I was diagnosed for me, it was like everything collapsed and I don´t want any more partners, I don´t want any more men…I don´t know why I’m scared, I imagine that I can become infected with something else because of them. So, I can´t tell you that tomorrow or the day after I´m going to find a partner and have sex again, I can´t” (VB 7)

Wanting to be quiet refers to not feeling sexual desire and not wanting to be intimately touched by her partner. Women are afraid of sexual relations; they do not want to feel sexual pressure.

“Now I´m fine on my own, I enjoy my solitude, I don´t want to be pressured and being with someone I would feel a bit pressured to have sex” (VB 15)

“Now I want to be calm, if I want, I get up, if I want, I cook, if I want, I wash, I don´t want to be pressured…, but with a partner you don´t have your own life, you have to be dependent on what they want” (VB 11).

Dimension 4: To please the partner

This dimension talks about the concern to sexually please their partners. They understand that sexual matters are important for men and therefore they feign pleasure and silence the pain so that they remain satisfied. They accept and promote the incorporation of other non-penetrative sexual enjoyment alternatives to satisfy their partners, as well as giving their partners freedom in terms of the affective bond.

The woman is considered herself in a role, which is to “sexually comply with her partner”, bearing the lack of sexual desire or discomfort that this involves. In turn, if she cannot “fulfill” with this role, it comes the guilt and the need to know the satisfaction degree reached by her partner.

“I do it just to make him happy, but I don´t feel comfortable, I don´t enjoy it, it hurts, it´s not the same…” (GF 3)

“But I ask him first, if he enjoyed as much as before, if he has found any difference, because it seems to me that must different than before and then he asks me the same and I deny. But it has been only twice and since I´m just starting I don´t pay too much attention to it. He tells me he enjoys it just the same” (VB 14)

The need to lie and feign sexual satisfaction in front of her partner is revealed, hiding the discomfort so that he doesn´t worry and thinks that she also enjoys the relation.

“Sometimes I remain in silence so that he can properly finish, and I keep myself toughing it out, even if it hurts” (VB2)

“He asks me if I felt, if I liked it, but I lied to him, I tell him it was fine so he doesn´t worry” (VB 14)

It gives them peace of mind to incorporate other non-penetrative sexual alternatives in order to sexually satisfy them.

“We have talked about it anyway, because we freely talk about those issues, so we look for ways to make it painfulness, some other ways, do you understand?” (VB 13).

“But as woman I worry about it, but it makes me feel better that we can have fun in other ways too” (VB 12)

Faced with the inability to make their partners sexually happy because of their disease, they prefer to break up with their partners and set them free so that another woman can fulfill this role:

“I also told him, that maybe because of this we were to change, I even told him that if he wanted, he would find another one, or if he wanted to break up, I would understand, because if he stayed, he would need to be really patience” (VB 14)

“I had told him that with this of my disease it was time to restart his life in some other place and find another woman who could make him happy, that I had problems and that I would have no time for him” (VB 12)

Dimension 5 Infidelity or Abandonment by the partner

This dimension addresses reports of fear by women to abandonment or infidelity by their partners, as well as the questioning that the same partners make to the women as a result of their sexual behavior.

Concern of being abandoned by their partners or being cheated is revealed, associating the sexual dissatisfaction that their condition causes with the perceived distance from their partners:

“I have had fears for my partner due to insecurities…I imagined that he could leave me and have a child with another woman. Insecurities that he could leave me because of the condition I had. I have talked about it, but he gets angry... (smiling). He tells me not being a fool, that how can I imagine those things, that he is with me, that he fell in love with me” (GF2)

“I was never afraid of being abandoned, but of him looking for someone else. I was not afraid, but it was not pleasant thinking this could happen, I don´t know if I could have tolerated that” (VB9)

Some interviewees have felt questioned by their partners in front of alleged infidelity, believing that they are not loved anymore:

“In the sexual aspect he says that he understands, and he understands it hurts me and he does not demand it. In fact, he has never been so demanding, outspoken, but sometimes you notice them, because men get in a bad mood and sometimes, he tells me he will have to find another one, is like if I’m not useful anymore, something like that, he has told me” (VB 11)

“He believed in a certain moment that I had stop loving him and that there was another one…” (VB 14).

Discussion

The presence and company by the partner turn out to be a relevant dimension in the evolution that women live during recovery. However, while some women appreciate the closeness of their partner in the process of their disease and treatment, both in the family and sexual spheres, some others on the other hand, feel sexual pressure from their partners, in addition to experiencing lack of support and affective distance. This finding is consistent with the literature, where a journey through a sexual adaptation is described where the support of the partner constitutes a cornerstone to determine the success of this process [8,17]. This research confirms the importance of affective and sexual communication in the couple, because when the level of sexual dialogue is more open, the partners are usually more tolerant and capable as a couple to better face the adaptation process that involves recovery [18]. However, with couples with less solid ties and difficulties prior to the disease, the conflict becomes even more evident when new problems in the sexual sphere are added, showing the need for professional support that involves the partners [19].

Those who know the relationship between the CUca with the Human Papilloma Virus, associate this cancer with guilt, promiscuity, they fear being infected again or have the cancer reappeared, blaming the partner for their disease, an important factor for not wanting to restart a sexual life or having a partner again, a situation also found in the literature, where women modify the perception of their sexuality generating feelings of shame, guilt or rejection towards their partners”. The promiscuity and infidelity of their partners is usually a factor which is present in these women, as well as the characteristic of maintaining several sexual partners by the woman or her partner is considered by the literature to be an important behavior risk for infection” [20-23].

Women avoid sexual relations and do not want to feel sexual pressure from their partners, this is why some of them opt for partner rejection and isolation. Guilt and shame prevail in addition to the fear of sexual relations and/or of having a partner. Even when they want to feel loved and trusted again, they feel physically and emotionally unprepared and want to protect themselves from a disease contracted through sexual intercourse. According to the literature there is a stigma surrounding sexually transmitted infections in these women, creating a psychological and emotional burden as well as a stereotyped self-perception of the dynamics of their sexuality that can explain the behavior of avoiding, moving away or rejecting their partner [24-27]. In the same way, the Merle Mishel Model supports the appearance of these emotions and adopted isolation, as a protection mechanism in response to the uncertainty generated by this disease [28].

Some participants maintain sexual relations despite the pain or discomfort it may cause them, just to please their partners and fulfill their role as women, even though there is neither sexual desire nor enjoyment in them. While the woman faces the loss of her health and everything related to her disease, she begins to feel herself powerless, useless and a burden or obstacle for her partners to achieve their individual goals and the joy that a satisfying sexual relationship can give them, showing concern for pleasing her partner, fulfilling her role as a woman and leaving away the constant threat of abandonment by her partner [27]. Similarly, the literature points out that they experience guilt and sexual communication problems with their partners, by associating sexual abstinence with potential partner dissatisfaction, becoming a predictor factor of sexual dysfunction [20]. In this way, sexually pleasing their partners can become a responsibility that they assume, as well as a trial or challenge of permanent concern [29].

Experiences of infidelity with their partners are part of their life stories, so the fear of infidelity and abandonment are a constant concern and also present in their partners, as an explanation for the woman´s lack of desire, expressing her concern when she perceives some distancing from her partner, revealing the importance of maintaining and protecting this affective relationship. The literature agrees on the fear of losing their partners by not sexually satisfying them, the fear of invisibility and disinterest or lack of attraction in the face of changes in their image emerge disturbingly, situation aggravated by misinformation and low professional support [30,31]. Likewise, studies show that oncology patients usually opt for secure adherences, in this way the partner and the family are the bonds chosen as affective bonds and are considered protective factors against the threat of abandonment or loneliness, since it gives them confidence and security [29,32,33].

Conclusions

The accompaniment of the partner in the sexual sphere is significant for women, especially when they respectfully assume sexual abstinence until they can fully resume sexual activity. In the absence of accompaniment, they prefer to be alone, without a partner, calm and not pressured in the sexual sphere. When they are aware about CUca, they associate the disease with dirt, promiscuity, blaming their partner for cancer. They fear being re-infected by their partners and/or that the cancer will reappear, an important component for not wanting to have a partner again or wanting to postpone restarting their sexual life. Nevertheless, they fear an eventual infidelity or abandonment by their partners, so they are capable of accepting non-penetrative sexual alternatives and/or having sexual relations, assuming coital pain and lack of sexual enjoyment, just to satisfy their partners, in addition to fulfill the role of woman they feel they have to fill. In this way, the prevalence and linkage of socially established cultural patterns that must be necessarily contextualized in these women such as familism, male chauvinism and marianism, which seem to intervene and powerfully influence the process of recovering their sexual health are revealed in the stories. Therefore, it is recommended to incorporate them when developing future health interventions.

In the sexual sphere, the couple undergoes important changes after the diagnosis and treatment of CUca that require professional attention. The need to investigate, educate and accompany the couple in the sexual sphere is noted. It is suggested in future studies to incorporate the perspective of the partner in the search for more information that allows the health professional to efficiently advise the couple.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (World Health Organization) (2018) Papilomavirus humanos (PVH) y cáncer cervicouterino (Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) and cervical uterine cancer) [Internet]. World Health Organization.

- American Cancer Society (2017) Survivorship and Quality of Life [Internet]. Investigación y Calidad de Vida.

- Pfaendler KS, Wenzel L, Mechanic MB, Penner KR (2015) Cervical Cancer Survivorship: Long-term Quality of Life and Social Support. Clinical Therapeutics [Internet] 37(1): 39-48.

- Sociedad española de Oncología Médica (Spanish Society of Medical Oncology) (2017) Cáncer Cérvico Uterino (Cervical Uterine Cancer) [Internet]. Cáncer Cérvico Uterino (Cervical Uterine Cancer).

- Zhou W, Yang X, Dai Y, Wu Q, He G, et al (2016) Survey of cervical cancer survivors regarding quality of life and sexual function. J Cancer Res Ther [Internet] 12(2): 938-44.

- Robinson L, Miedema B, Easley J (2014) Young Adult Cancer Survivors and the Challenges of Intimacy. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology [Internet] 32(4).

- Shi Y, Cai J, Wu Z, Jiang L, Xiong G, et al (2020) Effects of a nurse-led positive psychology intervention on sexual function, depression, and subjective well-being in postoperative patients with early-stage cervical cancer: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies [Internet] 111(74): 103768.

- Sekse RJT, Hufthammer KO, Vika ME (2017) Sexual activity and functioning in women treated for gynecological cancers. Journal of Clinical Nursing [Internet] 26(3-4): 400-10.

- Vermeer WM, Bakker RM, Kenter GG, Stiggelbout AM, ter Kuile MM (2016) Cervical cancer survivors’ and partners’ experiences with sexual dysfunction and psychosexual support. Support Care Cancer [Internet] 24: 1679-87.

- Wilson C, McGuire D, Rodgers B, Elswick R, Menendez S, et al. (2021) Body Image, Sexuality, and Sexual Functioning in Cervical and Endometrial Cancer: Interrelationships and Women’s Experiences. Cancer Nurs [Internet] 44(5): 52-86.

- Creswell J (2009) Research Design. Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches [Internet]. 3a. Edicion. SAGE, editor. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Los Angeles: University of Nebraska-Lincoln, pp.143-171.

- 64a Asamblea General, FB octubre 2013 (2014) Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM. Principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos (2013). Biodebate 73: 15-18.

- Krippendorff K (2019) Metodología de análisis de contenido: teoría y práctica (Content analysis. An introduction to it. Methodology) [Internet]. 4a. Edició SAGE Publications Ltd., editor. Los Ángeles: University Pennsylvania, p.279.

- Hernández Sampieri R, Fernández C, Baptista P (2014) Capítulo 14: Recolección y análisis de los datos cualitativos (Chapter 14: Collection and analysis of qualitative data). In: McGraw Hill, editor. Metodología de la Investigación (Investigation Methodology) [Internet]. Sexta Edic. Mexico, pp.427-634.

- Arias MM (2000) La Triangulación Metodológica: sus principios, alcances y limitaciones (Methodology triangulation: principles, scopes and limits). Invest Educ Enferm [Internet] 18(1): 13-26.

- Arias MM, Giraldo C (2011) El rigor científico en la investigación cualitativa (Scientific rigor in qualitative research). Invest Educ Enferm [Internet] 29(3): 500-14.

- Bakker RM, Kenter GG, Creutzberg CL, Stiggelbout AM, Derks M, et al. (2017) Sexual distress and associated factors among cervical cancer survivors: A cross-sectional multicenter observational study. Psycho-Oncology 26(10): 1470-1477.

- Liberacka-Dwojak M, Izdebski P (2021) Sexual Function and the Role of Sexual Communication in Women Diagnosed with Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review. Int J Sex Heal [Internet] 33(3): 385-95.

- García Padilla D, García Padilla M del P, Ballesteros B, Novoa M (2003) Sexualidad y Comunicación de Pareja en mujeres con Cáncer de Cérvix: Una Intervención Psicológica (Sexuality and Couple Communication in women with Cervical Cancer: A Psychological Intervention). Universitas Psychologica [Internet] 2(2): 199-214.

- Cano-Giraldo S, Caro-Delgadillo F, Lafaurie-Villamil M (2017) Vivir con cáncer de cuello uterino in situ: experiencias de mujeres atendidas en un hospital de Risaralda, Colombia, 2016. Estudio Cualitativo (Living with cervical uterine cancer in situ: experiences of women treated at a hospital in Risaralda, Colombia, 2016. Qualitative Study). Revista Colombiana de Obstetricia y Ginecología (Colombian Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology) [Internet] 68(2): 112-9.

- Cordero J, García M (2015) Citologías alteradas, edad, inicio de las relaciones sexuales, número de parejas y promiscuidad. Revista de Ciencias Médicas 21(2): 357-370.

- Grion R, Abullet L, Baccaro F, Abullet A, Vaz F (2016) Sexual function and quality of life in women with cervical cancer before radiotherapy: a pilot study. Arch Gynecol Obstet [Internet] 293: 879-86.

- Léniz J, van de Wyngard V, Lagos M, Barriga MI, Puschel Illanes K, Ferreccio Readi C (2014) Detección precoz del cáncer cervicouterino en Chile: tiempo para el cambio. Revista Médica de Chile (Early detection of cervical uterine cancer in Chile: time for change. Chilean Medical Journal) [Internet] 142(8): 1047-55.

- Arellano Gálvez, M del C, Castro Vásquez, M del C (2013) El estigma en mujeres diagnosticadas con VPH, displasia y cáncer cervicouterino en Hermosillo, Sonora. Estudios Sociales (Hermosillo, Son.) 21(42): 259-278.

- Lichtenstein B, Edward W. Hook III E, Sharma A (2005) Public tolerance, private pain: Stigma and sexually transmitted infections in the American Deep South. Cult Health Sex [Internet] 7(1): 43-57.

- Newton D, PcCabe M (2005) The impact of stigma on couples managing a sexually transmitted infection. Sexual and Relationship Therapy 20(1): 51-63.

- Osamor PE, Grady C (2018) Autonomy and couples’ joint decision-making in healthcare. BMC Medical Ethics 19(1): 1-8.

- Mercado J (2017) Incertidumbre frente a la Enfermedad: Aporte de Merle Mishel a la Enfermería (Uncertainty in the face of the Disease: Merle Mishel´s contribution toNursing). Revisalud Unisucre [Internet] 4072(1): 31-5.

- Retana-Franco BE, Sánchez-Aragón R (2020) El peso del apego y de la cultura en las estrategias de rompimiento amoroso percibidas por los abandonados. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 23(1): 53-65.

- Corradina J, Urdaneta J, García N, Contreras N, Nasser Baabe M (2017) Calidad de vida en supervivientes al cáncer de cuello uterino (Quality of life in cervical uterine cancer survivors). Rev Venez Oncol [Internet] 29(3): 219-28.

- De Araujo S, De Olivreira T, Sanches M, Dos Santos M, De Almeida A (2016) Representaciones sociales acerca de la enfermedad de las mujeres con cáncer cérvico uterino (Social representations about the disease of women with cervical uterine cancer). Rev Latino-Am Enfermagem [Internet] 8(1): 3679-90.

- Flórez-Rodríguez YN, Sánchez-Aragón R (2021) La pareja con cáncer: ¿de qué manera el estilo de apego afecta la soledad, el bienestar subjetivo y la satisfacción con la relación? Psicología y Salud (The cancer couple: How does attachment style affect loneliness, subjective well-being, and satisfaction with relationship?) (2): 31-43.

- Guzmán M, Contreras P (2012) Estilos de apego en relaciones de pareja y su asociación con la satisfacción marital. Psykhe 21(1): 69-82.

-

Antonieta Silva M* and Teresa Urrutia. Impact of the Diagnosis and Treatment of Cervical Cancer on the Sexual Health of the Couple. Iris J of Nur & Car. 4(5): 2024. IJNC.MS.ID.000597.

-

Complementary therapy; Psychiatric disorder; Depression; Conventional therapy; Vitamin D; Medication

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.