Research Article

Research Article

Stepwise Addition Evaluation of Soybean Production Systems

Richard Edward Turner1*, Wayne Ebelhar2, Steve Martin3, Teresa Wilkerson4, Bobby Golden5, and Trent Irby6

1*Assistant Research Professor, College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, University of Missouri, USA

2Retired Professor, Delta Research and Extension Center, Mississippi State University, USA

3Extension Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics, Mississippi State University, USA

4Assistant Research Professor, Department of Agricultural Science and Plant Protection, Mississippi State University, USA

5Director of Agronomy for Simplot Grower Solutions, USA

6Professor, Department of Plant and Soil Sciences, Mississippi State University, USA

Richard Edward Turner, Assistant Research Professor, College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, University of Missouri, USA

Received Date:December 05, 2025; Published Date:December 11, 2025

Abstract

Soybean Glycine max (L.) is grown for grain on more hectares in Mississippi than any other row crop. The objective of this research project was to evaluate the interaction of row configuration (Single-Row [SR] compared to Twin-Row [TR]) and two planting populations, 258,300 (MP) and 387,500 (EHP) seed ha-1(whole plot), with five commonly used management strategies used in Mississippi (subplot). Management strategies included fungicide (F), desiccant (F+D), P and K fertilization (F+D+PK), and N and S fertilization (F+D+PK+NS) all compared to standard practice control (C). A multi-year field study was evaluated near Stoneville, MS at the Delta Research and Extension Center (DREC) on a Commerce silty clay loam. Grain yield was 2.5% greater when using the TR system when compared to SR systems. Planting population EHP increased grain yield by 1.6% when compared to MP population. Addition of fungicide (F) increased soybean grain yield by 4.9% when compared to no fungicide application (C). Based on economic analysis, the data suggest using the TR configuration at a MP population and using no additional management (C) or fungicide only application (F). Routine applications of fertilizer P, K, N or S without soil testing could lead to undue expense with no economic return. Scouting usually pays for itself both when problems are present and when they are not.

Introduction

Two strategies to manage disease pressure have emerged recently: i) scout for disease pressure, then make the appropriate fungicide application or ii) make a blanket (automatic) fungicide application at the growth stage (R4). Allen [1] concluded that any application made before R4 will not result in season long residual activity. Results also showed that 50-60% of the time fungicide provides a break-even response when applied at R3 to R4 under a high yielding environment. Timing for the harvest aid application to soybean production application is critical. Timely application allows the producer to harvest 3 to 14 days sooner when compared to an untreated crop if applied at growth stage R6.5 and environmental conditions are favorable [2,3]. However, desiccation application too early in the growing season can also reduce yield. Boudreaux [3] concluded that application of desiccant before the soybean growth stage (R6.5) had the potential to reduce yield by 17%. If harvest aid is applied and harvest occurs in a timely manner then no yield loss, grain weight decrease, or quality can be affected [4-6]. Whigham and Stoller [6] concluded that paraquat shortened the days until harvest when compared to other desiccation herbicides. Paraquat had a slight effect on seed germination, loss of seed weight, and yield loss was greatest when compared to other herbicides. However, when applied 14 d before harvest there was not a significant difference between treated and untreated plots.

Soybean fertilization is a popular practice to maximize yields and is especially important on nutrient limited soils. Bhangoo and Albritton [7] showed a yield increase from fertilization with nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K) combinations that ranged from 14.7 to 32.8% compared to an untreated check in Southeast Arkansas. Their data showed a 14% increase from N fertilization, 7.4% increase to P fertilization and 19.4% increase from K fertilization. Soil tests revealed soils that were low in available P and exchangeable K and should have responded to both P and K fertilizer applications. Nitrogen increased yield all three years of study, K only increased two years and P one year. This variability in fertilization response is likely due to nutrient buildup over the course of the experiment.

Materials and Methods

Description of Sites

Multi-year field experiments, (two each in 2017, 2018, and 2019) were conducted to determine the economic impact of soybean agronomic inputs in the Mississippi Delta. Studies were established at the Mississippi State University Delta Research and Extension Center near Stoneville, MS. The experiment was conducted on fields composed of a Commerce silty clay loam soil that is commonly cropped to soybean within Mississippi and rotated with corn.

Composite soil samples were collected from each plot (n=160) at a depth of 0 to 15-cm from each experimental site after harvest. Each composite sample consisted of eight to ten, (2.5-cm diameter) cores. Soil samples were air-dried, ground to pass through a 2-mm sieve, and extracted using Lancaster. Lancaster extracts were analyzed using inductively coupled atomic plasma spectroscopy (ICPS), [8]. Soil water pH was determined in a 1:2 soil weight: water volume ratio using a glass electrode.

Each year, weeds were controlled with a mixture of cloransulam-methyl at 0.002 kg ai ha-1 (N-[2-carbomethoxy-6- chlorophenyl)-5-ethoxy-7-fluoro (1,2,4)triazolo-[1,5-c]pyrimidine- 2-sulfonamide), plus 1.4 kg ai ha-1 S-metolachlor (2-chloro-N- (2-ethyl-6-methylphenyl)-N-[(1S)-2-methoxy-1-methyethyl] acetamide), plus 0.7 kg ai ha-1 glufosinate-ammonium (RS)-2- Amino-4-(hydroxyl(methyl)phosphonoxyl)butanoic acid) applied to the soil surface prior to soybean emergence. This was followed by a V3 growth stage application mixture of S-metolachlor at 1.3 kg ai ha-1 (2-chloro-N-(2-ethyl-6-methylphenyl)-N-[(1S)-2-methoxy-1- methyethyl] acetamide) plus 0.7 kg ai ha-1 glufosinate-ammonium (RS)-2-Amino-4-(hydroxyl(methyl) phosphonoxyl) butanoic acid). Soybean management closely followed the Mississippi State University Extension Service recommendations for pest and irrigation management.

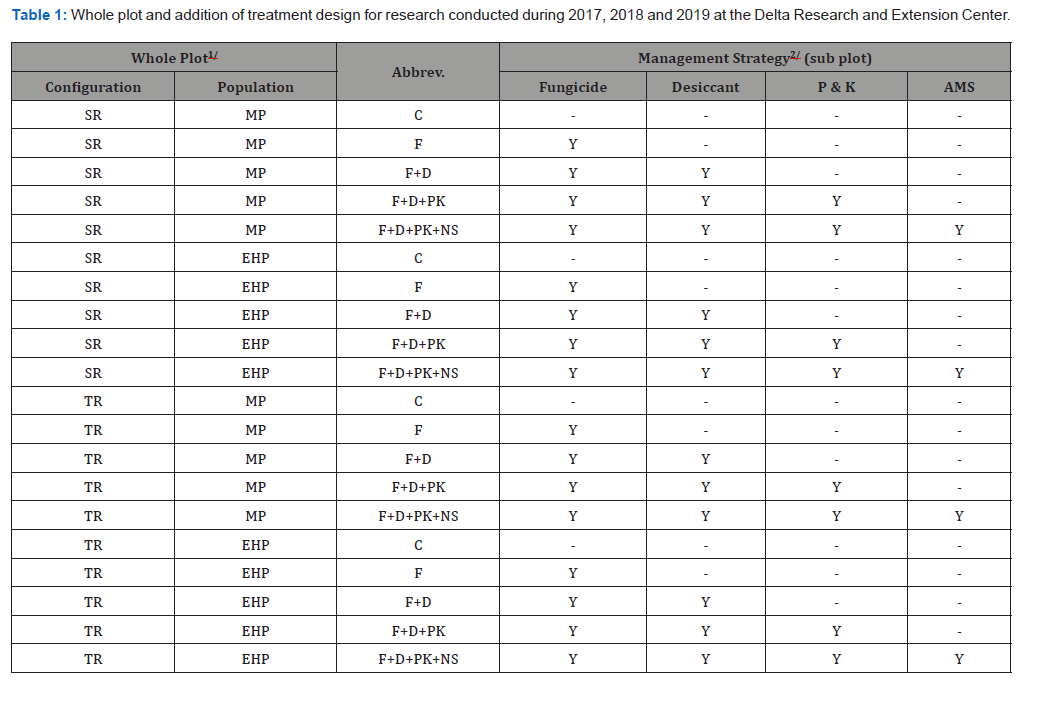

Treatments

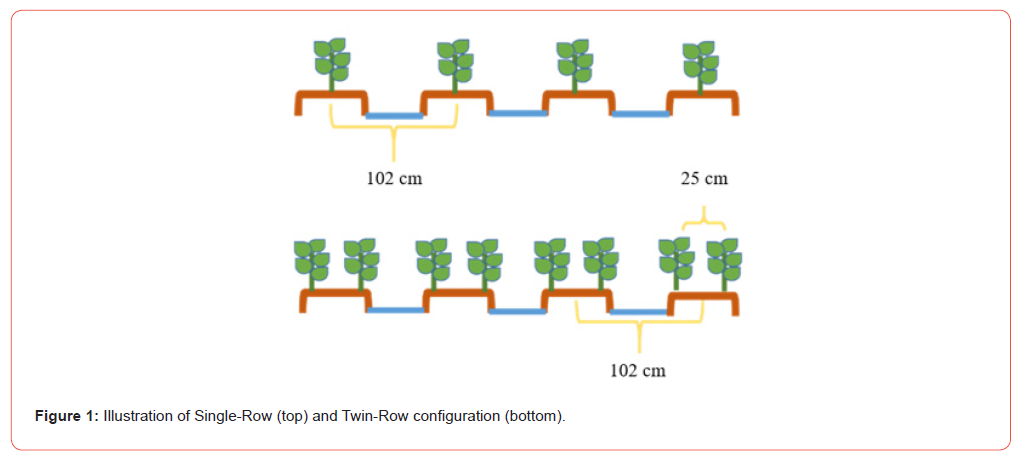

The soybean cultivar ‘Credenz 4748 LL’ was seeded into conventionally tilled plots measuring 4.06 × 30.48-m at 258,300 seed ha-1 to represent the medium planting population (MP) and 387,400 seed ha-1 to represent the extra high planting population (EHP) via John Deere Max Emerge 2 planter (John Deere, Deer and Company, One John Deere Place Moline, IL) for the SR system. A Twin-Row Monosem planter (Monosem Inc. 1001 Blake St. Edwardsville, KS) was used to plant each population in the TR system. Each plot consisted of four beds spaced 101.6 cm apart separated by a perpendicular alley 5-m across (Table 1 for treatment layout and Figure 1 for row configuration design). Replications were established down the slope based on drainage and irrigation direction.

Management strategy applications consisted of: i) control (C), ii) fungicide applied at R4 (F), iii) fungicide at R4 + desiccant applied at R7 (F+D), iv) fungicide at R4 + desiccant applied at R7 + 0-0-60 and 0-46-0 applied at crop emergence (F+D+PK) and v) fungicide at R4 + desiccant applied at R7 + 0-0-60 and 0-46-0 + AMS applied at crop emergence (F+D+PK+NS). Fertilizer applications included ammonium sulfate (AMS; 21-0-0-24S), muriate of potash (0-0-60), and triple superphosphate (0-46-0). Sources were chosen for their availability and common use in the mid-southern U.S. All fertilizer sources were broadcast by hand (simulated aerial or ground application) to randomly assigned plots at 112 kg P2O5 ha-1, 112 kg K2O ha-1, and 112 kg AMS ha-1. Pre-weighted samples were applied and incorporated by cultivation.

1/ (SR = single-row; TR = twin-row; MP = medium; EHP = extra high).

2/ management strategies [C = control; F = fungicide @ R4; F+D = F + desiccant @ R7; F+D+PK = F+D+P and K fertilization at emergence; F+D+PK+

NS = F+D+PK+ Nitrogen and Sulfur (AMS) fertilization at emergence].

Fungicide applied at R4 soybean growth was 0.5 L ha-1 of Quadris Top SBX (Syngenta Crop Protection AG, P.O. Box CH-4002 Basel, Switzerland) applied at 15 L ha-1 spray volume. This material is a combination of difenoconazole and azoxystrobin. The fungicide was designed to represent a “blanket” automatic application that can be used without scouting for disease pressure. A desiccation was applied at R7 using 1.2 L ha-1 of GramoxoneTM (Syngenta Crop Protection AG, P.O. Box CH-4002 Basel, Switzerland) paraquat dichloride (1,1’-dimethyl-4,4’-bipyridinium dichloride) plus 0.25% COC applied at 15 L ha-1 spray volume.

Measurements/Data Collection

A small-plot combine (Kincaid Equipment, 210 West First St., P.O. Box 400; Haven, KS) was used to harvest the middle two rows of each plot. Harvest moisture and estimated bushel test weight were determined from a sub sample with a Dickey-John model GAC 2100b moisture meter (Dickey-john, 5200 Dickey John Rd. Auburn, IL). Soybean yield was collected and adjusted to 13% moisture content for yield analysis. A sub sample was collected at harvest to determine grain moisture and bushel test weight.

Statistics

Individual experiments were designed as a split plot with twenty treatment arrangements using four replications and two site years in each year (2017 -2019). Means for yield component data were calculated across replicates for each site year and 3-yr average for each measurement. Type III statistics were used to test treatment effects, and least square means were separated at the p < 0.05 significance level using Fisher’s Protected LSD. Classified by site year, data were subjected to ANOVA using the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS v. 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. 100 SAS Campus Drive Cary, NC 27513-2414, USA). Least square means were calculated, and mean separation (p < 0.05) was produced using PDMIX800 in SAS, a macro for converting mean separation output to letter groupings if a significant response occurred [9].

Results and Discussion

Grain Yield

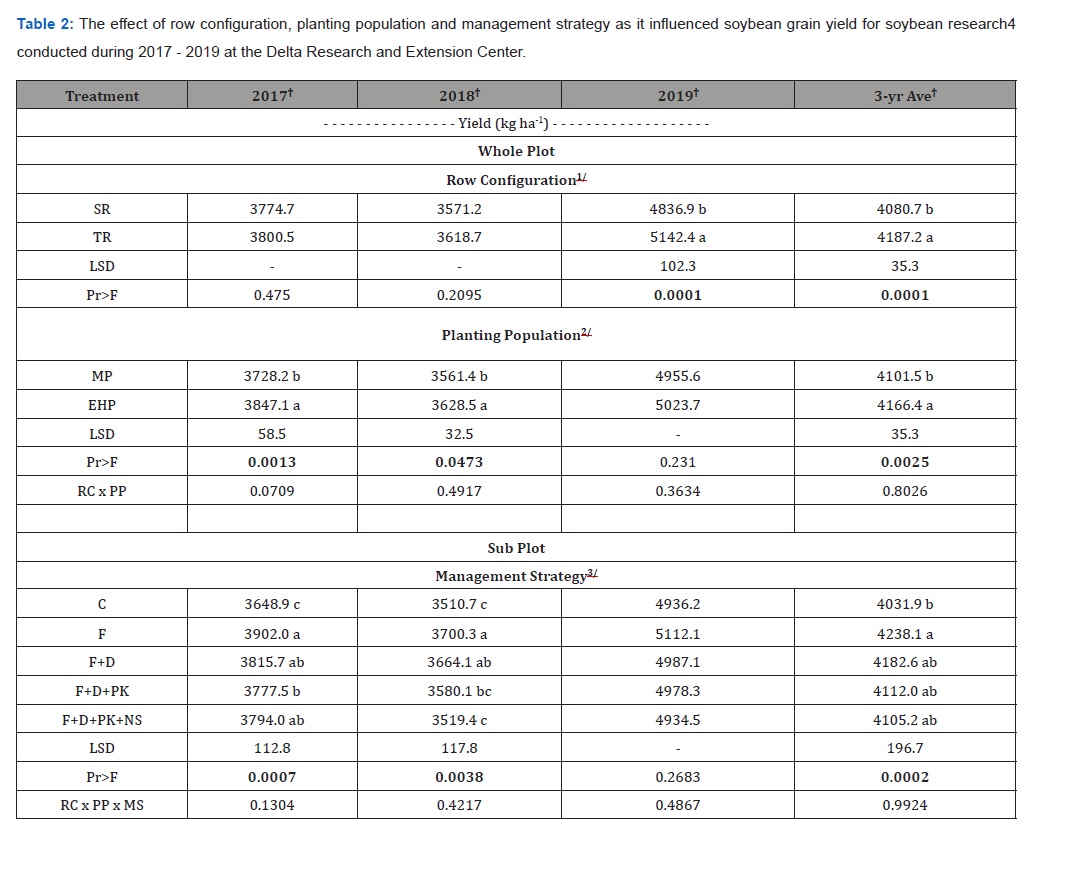

In 2019 and 3-yr average, soybean grain yield was greatest when using the TR system compared to SR by 5.9 and 2.5%, respectively (Table 2). In 2017 and 2018, differences in soybean grain yield when comparing TR to SR were 0.7 and 1.3%, respectively (differences not significant). Bruns [10] in Mississippi and Mascagni [11] in Louisiana reported increased soybean grain yields by up to 13% when comparing TR to SR systems. They reasoned that increased soybean grain yield was likely due to reduced plant-to-plant competition and increased pods plant-1.

For business management and the economy, this marks a significant shift: loyalty is transactional and based on proven effectiveness. Business management strategies must pivot from image creation to demonstrating functional value and operational transparency, recognized as the best marketing is a product that consistently delivers on its promise.

are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

2/ (mean of 8 replicates and 2 row configurations with 5 management strategies (n = 80). † (Means within a column followed by different letters are

significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

3/ (means of 8 replicates and 2 row configurations with 2 planting populations (n = 32). † (Means within a column followed by different letters are

significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

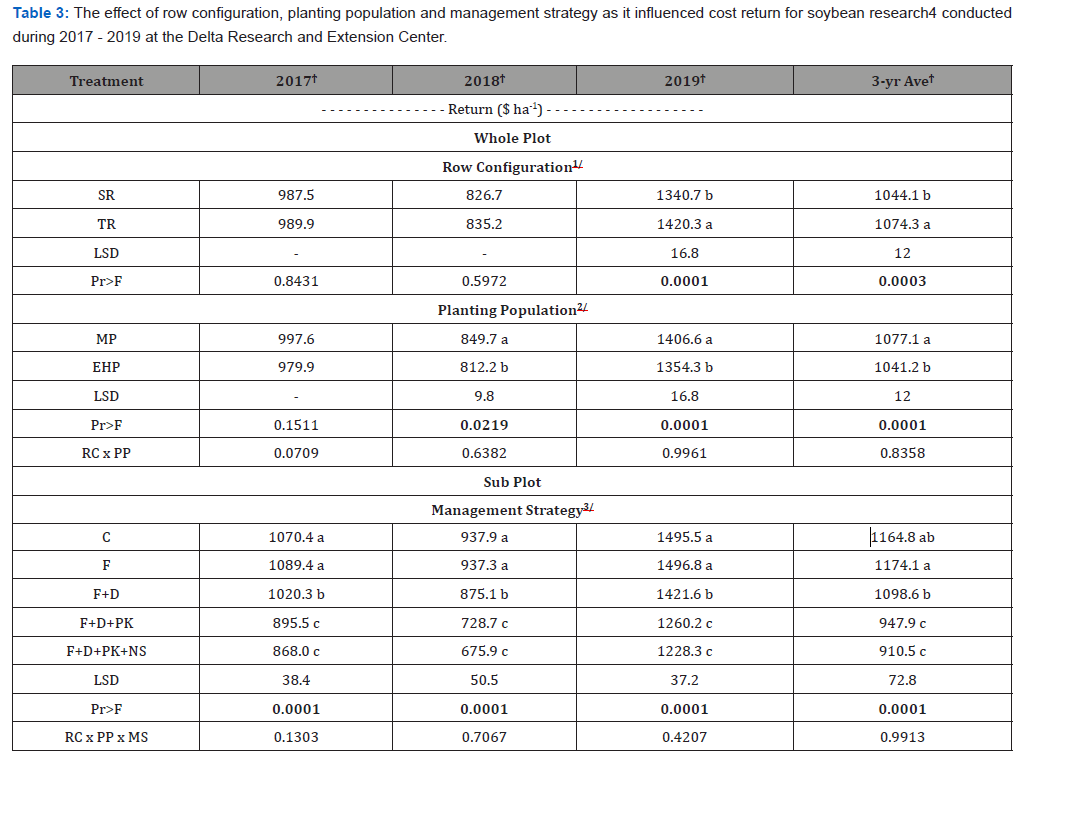

4. Research sponsored in part by the Mississippi Soybean Promotion Board (SR = single-row; TR = twin-row; MP = medium; EHP = extra high).

In 2017, 2018, 2019 and 3-yr average, differences in soybean grain yield when comparing EHP population to MP population was 3.1, 1.8, 1.4 and 1.6%, respectively (not significant in 2019). Stivers and Swearingin [12] reported that small skips in soybean stand will not reduce grain yield. However, large skips do have the potential to reduce grain yield. If a thin stand is uniform early, soybean can compensate and similar yields can be achieved over a large range of soybean populations [13-16]. In 2019, averaged across both populations soybean grain yield was 27.9% greater when compared to 2018.

For the 3-yr average, F increased soybean grain yield when compared to no additional management control (C). Addition of management strategies other than fungicide never increased soybean grain yield. In 3-yr average, use of fungicide increased soybean grain yield by 4.9% when compared to no management (C). Mahoney, et al. [17] reported a 4.5% soybean yield increase when utilizing a fungicide applied at R3 in Ontario, Canada. Fungicide application increased soybean grain yield between 253 kg ha-1 in 2017 to 175.9 kg ha-1 in 2019 when compared to a no-fungicide management. Nelson [18] in Missouri reported yield increases up to 390 kg ha-1.

Use of desiccant consistently resulted in a reduction in grain yield when compared to F (fungicide alone). In 3-yr average, desiccant reduced soybean grain yield by 55.5 kg ha-1 this was mainly due to a 42% increase in seed loss at the time of harvest compared to a non-desiccant (C and F) treatment. When comparing F to F+D, a yield loss of 1.3% occurred due to application of desiccant. Philbrook and Oplinger [19] reported an average yield loss of 10% due to shattering, lodging and harvesting; losses could be greater when using a desiccant. During this study adverse weather conditions occurred in 2017 and 2018 in the form of excess rainfall from nearby hurricanes. Plots that received a desiccant could not be harvested until all plots were 15% moisture or less. Delayed harvest after desiccant application may have contributed to some yield 0decline when compared to non-desiccant (C and F) treatments. Recommendations call for harvest within 10 – 14 days following the desiccant application.

Addition of fertility (P and K) or (N and S) failed to increase soybean grain yield. Research reported in literature has shown application of N has shown to reduce the number of nodules formed on soybean roots [20-22] consequently maintaining or reducing soybean grain yield [23,24] reported increases in soybean grain yield up to 9% when applying K fertilizer on already medium to high K level soils. Kamprath and Jones [25] reported an increased soybean yield response when soil S was below 4 mg kg-1 and unresponsive at soil levels of 8 mg kg-1.

Economics

In 2019 and 3-yr average, the TR system resulted in a greater net profit when compared to the SR system (Table 3) even though TR equipment cost $6.35 more ha-1. In 2019 and 3-yr average, the TR system resulted in 5.6 and 2.8% greater net profit when compared to SR system, respectively. The increase in net profitability during these years was due to increased soybean grain yield in those years associated with TR configuration. In 3-yr average, the TR system produced $30.20 ha-1 more compared to SR that surpassed cost for increased operation costs. Earlier, Bruns in Mississippi, reported an economic advantage when comparing TR to SR systems. If herbicide applications can be reduced, using the TR system then economic benefit would be even greater when compared to the SR system. If TR can increase grain yield of other grain crops grown in the region such as corn, then equipment costs can be spread over additional production hectares.

1/ (mean of 8 replications and 2 planting populations with 5 management strategies (n = 80). † (Means within a column followed by different letters

are significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

2/ (mean of 8 replicates and 2 row configurations with 5 management strategies (n = 80). † (Means within a column followed by different letters are

significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

3/ (means of 8 replicates and 2 row configurations with 2 planting populations (n = 32). † (Means within a column followed by different letters are

significantly different at P ≤ 0.05.

4 Research sponsored in part by the Mississippi Soybean Promotion Board (SR = single-row; TR = twin-row; MP = medium; EHP = extra high).

In 2018, 2019, and 3-yr average, MP was more profitable when compared to EHP population even though EHP population produced greater soybean grain yields in 2017 and 3-yr average. This is due to the increased cost associated with planting seed. Similarly, De Bruin and Pedersen [26] reported small gains from increased planting populations did not pay for the additional planting seed required. Planting population MP is 33% less seed planted ha-1 when compared to EHP population and net return was 3.3% greater for MP population. Planting population MP cost $116.13 ha-1 compared to EHP population cost at $174.20 ha- 1. The saving of $58.07 ha-1 on seed cost offsets the 64.9 kg ha-1 yield increase that is gained using the EHP population. These prices and differences will vary depending on the cost of seed and seed treatments.

Other management strategies never increased net profitability compared to no management. However, F was the only management strategy that produced similar profitability in all years of this study. Very little increases of 0.1% in net profitability were observed in 2018 and 2019 but the differences were not statistically significant. Use of foliar-applied fungicides are not always economical [17,27]. However, a 1.7% net profitability increase occurred in 2017. Changes in profitability of fungicide applications show the variability in disease presence across years and how an automatic application can be more beneficial in high disease pressure circumstances.

Management strategies that apply P and K fertilizer + cost of application cost have $131.23 ha-1, while ammonium sulfate fertilizer (21-0-0-24s) + application only cost $51.72 ha-1 (these values change depending on the annual cost of the fertilizer material). Heatherly et al, [28] reported that use of N fertilizer lowered net returns by $28 to $50 ha-1 (fertilizer prices could have been much different in 2003 as compared to 2019). Fertilizer additions often increase yield to cover cost of application and cost of product if soils are in the low category. Soils that are in the medium, high and extra high soil test categories tend to be less responsive when compared to field with low soil test values. Thus, the probability of response to added fertilizer goes down as soil test level goes up. Nitrogen additions to soybean often do not provide an economic return if fertilizer is applied to these fields [23,29-31]. The data presented justified the importance of a soil sample that cost approximately $17.30 ha-1.

Summary

The TR system also resulted in greater soybean grain yield when compared to the SR system. Planting population EHP resulted in greater grain yield, but the increase cost associated with higher planting seed reduced net returns. Use of harvest aids is important in Mid-South soybean production, especially when adverse weather conditions can be approaching such as long periods of rain, hard wind and hurricanes. When conditions such as these are long-range forecasted, harvesting R6.5 soybeans are critical, and harvest aids can and should be applied. Using additional fertility did not increase grain yields or net returns when applied without soil testing. Soil sampling is a much cheaper alternative when compared to automatic fertilizer applications if the fertilizer is not required. Soil fertility buildup to high levels in the soil can provide some security and backup should fertilizer price rise. However, high levels can also lead to potential field loss and damage to the environment. Use of fungicide (F) was the only management strategy that did not result in less net return when compared to no management applied. This data suggests that a producer should plant a MP population using the TR configuration, scout for disease pressure, and apply fungicide if needed while maintaining soil fertility (soil testing).

- Allen T (2015) Automatic soybean fungicide applications: Timing, product choice, rates in product combination.

- Boudreaux JM, JL Griffin (2011) Application timing of harvest aid herbicides affects soybean harvest and yield. Weed Technolo 25(1): 38-43.

- Boudreaux JM, JL Griffin, LM Etheredge Jr (2008) Utility of harvest aids in indeterminate and determinate soybeans. Proc. South. Weed Sci Soc 660: 91.

- Ratnayake S, DR Shaw (1992) Effects of harvest-aid herbicides on sicklepod (Cassia obtusifolia) seed yield and quality. Weed Technol 6: 985-989.

- Wilson RG, JA Smith (2002) Influence of harvest-aid herbicides on dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) desiccation, seed yield, and quality. Weed Technol 16(1): 109-115.

- Whigham DK, EW Stoller (1979) Soybean desiccation by paraquat, glyphosate, and ametryn to accelerate harvest. Agron J 71: 630-633.

- Bhangoo MS, DJ Albritton (1972) Effect of fertilizer nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium on yield and nutrient content of Lee soybeans. Agron J 64: 743-746.

- Soltanpour P, GW Johnson, SM Workman, JB Jones Jr, RO Miller (1996) Inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometry and inductively coupled plasma-mass spectroscopy. P. 91-140. In: D. L. Sparks (Ed.,). Methods of soil analysis. Part 3. SSSA Book Series 5. SSSA, Madison, WI.

- Saxton AM (1998) A macro for converting mean separation output to letter grouping In ProcMixed. PP: 1243-1246 in: Proceedings of the 23rd SAS users Group International. Car, NC: SAS Institute.

- Bruns HA (2011) Comparisons of single-row and twin-row soybean production in the mid-south. Agron J 103(3): 702-708.

- Mascagni HJ, E Clawson, D Lancios, D Boquet, R Ferguson (2008) Comparing single-row, twin-row configurations for Louisiana crop production. LA Agric 51(3): 16-17.

- Stivers RK, ML Swearingin (1980) Soybean yield compensation with different populations and missing plant patterns. Agron J 72: 98-102.

- Wilcox JR (1974) Response of three soybean strains to equidistant spacing. Agron J 66: 409-412.

- Lueschen WE, DR Hicks (1977) Influence of plant population on field performance of three soybean cultivars. Agron J 69: 390-393.

- Hoggard AL, JG Shannon, DR Johnson (1978) Effect of plant population on yield and height characteristics in determinate soybeans. Agron J 70: 1070-1072.

- Costa JA, ES Oplinger, JW Pendleton (1980) Response of soybean cultivars to planting patterns. Agron J 72: 153-156.

- Mahoney KJ, RJ Vyn, CL Gillard (2015) The effect of pyraclostrobin on soybean plant health, yield and profitability. Can. J. Plant Sci 95: 285-292.

- Nelson KA, P Motavall, WE Stevens, D Dunn, CG Meinhardt (2010) Soybean response to preplant and foliar-applied potassium chloride with strobilurin fungicides. Agron J 102(6): 1657-1663.

- Philbrook BD, ES Oplinger (1989) Soybean field losses as influenced by harvest delays. Agron J 81: 251-258.

- Beard BH, RM Hoover (1971) Effect of nitrogen on nodulation and yield of irrigated soybeans. Agron J 63: 815-816.

- Salvagiotti F, JE Specht, KG Cassman, DT Walters, A Weiss, et al. (2009) Growth and nitrogen fixation in high-yielding soybean: impact of nitrogen fertilization. Agron J 101(4): 958-970.

- Allos HF, WV Bartholomew (1959) Replacement of symbiotic fixation by available nitrogen. Soil Sci 87(2): 61-66.

- Welch LF, LV Boone, CG Chambliss, AT Christiansen, DL Mulvaney, et al. (1973) Soybean yields with direct and residual nitrogen fertilization. Agron J 65: 547- 550.

- Bharati MP, DK Whigham, RD Voss (1986) Soybean response to tillage and N, P and K fertilization. Agron J 78: 947-950.

- Kamprath EJ, US Jones (1986) Plant response to sulfur in the southerstern United States, In M.A. Tabatabai, Ed., Sulfur in Agriculture, Agron. Monogr. 27, ASA, CSSA, and SSSA, Madison, Wi 323-343.

- De Bruin JL, P Pedersen (2008) Soybean seed yield response to planting date and seeding rate in the Upper Midwest. Agron J 100(3): 696-703.

- Hanna SO, SP Conley, GE Shaner, JB Santini (2008) Fungicide application timing and row spacing effect on soybean canopy penetration and grain yield. Agron J 100: 1488-1492.

- Heatherly LG, SR Spurlock, KN Reddy (2003) Influence of early-season nitrogen and weed management on irrigated and nonirrigated glyphosate-resistant and susceptible soybean. Agron J 95(2): 446-453.

- Purcell LC, R Serraj, TR Sinclair, A De (2004) Soybean N2 fixation estimates, ureide concentration, and yield responses to drought. Crop Sci 44(2): 484-492.

- Ray JD, LG Heatherly, FB Fritschi (2006) Influence of large amounts of nitrogen applied at planting on non-irrigated and irrigated soybean. Crop Sci 46(1): 52-60.

- Johnson HS, DJ Hume (1972) Effects of nitrogen sources and organic matter on nitrogen fixation and yield of soybeans. Can. J. Plant Sci 52: 991-996.

-

Richard Edward Turner*, Wayne Ebelhar, Steve Martin, Teresa Wilkerson, Bobby Golden and Trent Irby. Stepwise Addition Evaluation of Soybean Production Systems. Iris J of Eco & Buss Manag. 3(3): 2025. IJEBM.MS.ID.000563.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.