Research Article

Research Article

How Mobile Working Impacts Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Cross-Sector Scholarly Literature Review

Inez Bijker1, Marvin Merken1, Yara Werdermann1 and Nadine Ladnar2*

1FOM University of Applied Sciences, Germany

2CEINDO-CEU Doctoral program in Economy & Law, IFS Institute for Strategic Finance, FOM University of Applied Sciences, Germany

Nadine Ladnar, CEINDO-CEU Doctoral program in Economy & Law, IFS Institute for Strategic Finance, FOM University of Applied Sciences, Essen, Germany.

Received Date: May 15, 2023; Published Date: June 12, 2023

Abstract

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the factors influencing job satisfaction of employees changed, as well as their organizational commitment to the current employer. Due to contact restrictions and temporary workplace closures, there was a need to rethink the way where work is performed. In 2019 12.8% of employees worked from home. In the next two years this percentage almost doubled to 24.8% in 2021. This paper applies a scholarly literature review approach and a case discussion comparing findings from literature with practical examples from Switzerland and the United States. The investigation answers the questions, (1) how job satisfaction is measured, (2) what influences organizational commitment, and (3) how mobile working models affects job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The findings include a number of influence factors, but a clear correlation between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Keywords:satisfaction; Organizational commitment; Mobile working

Introduction

In 2019 the number of individuals employed exceeded 45 million in Germany for the first time. Around 44 % of individuals employed who were older than 25 years stated, that they had been with their current employer for at least 10 years [1]. An additional 19% of individuals employed stated that they have been working for the company that they are employed at for at least 5 years. Over 95 % of these two groups are in permanent employment. The duration of the employment with the current employer can serve as an important indicator for stability, which influences the job satisfaction of employees [2].

Since 2020 the COVID-19 pandemic put another factor into play that influences job satisfaction of employees, as well as their organizational commitment to the current employer. Due to contact restrictions and temporary workplace closures, there was a need to rethink the way where work is performed. In 2019 12.8% of employees worked from home. In the course of the next two years this percentage almost doubled to 24.8% in 2021 [3].

Materials and Methods

Scientific research covers investigations on organizational commitment and job satisfaction. An overview of the literature is not provided. This research gap is closed with the present research article.

The objective of this paper is to show the influence of mobile working on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The paper focuses on office workers whose job offers the possibility to work remotely. The focus will be on the following questions:

1. How is job satisfaction measured?

2. What influences organizational commitment?

3. How do mobile working models affect job satisfaction and organizational commitment?

In this research paper, a scholarly literature review is applied. English and German literature between the years 1935 and 2022 is analyzed. A focus is on Journal articles and books published during this time. Furthermore, the research is enriched by governmental publications on employment.

Apart from the literature review, a case study is applied. Two examples from Switzerland and the US are described to enable a comparison between literature findings and practical evidence.

Results and Discussion

Overview of factors influencing job satisfaction

Chapter 1 already highlighted theories including several factors to influence job satisfaction positively or negatively. Herzberg, in his Motivator-Hygiene Theory, describes hygiene factors as dissatisfiers that can lead to dissatisfaction. Examples are hard facts that clearly define the job in an organization, such as pay, position and the associated prestige, but also working conditions and policy. Likewise, however, he also describes the motivations that are defined as satisfiers and can generate satisfaction. These include various subjective factors. Is the work valuable, demanding, or is the performance recognized? In addition, one’s own development opportunities and the job itself also play a major role. In the following we will describe different approaches to measure how these examples and other factors influence job satisfaction. Improving human relations by involving employees and treating them with respect also increases job satisfaction and the motivation of individual employees to work and thus promotes employee performance. This finding is also known as the Hawthorne effect. Hawthorne’s study initially focused on the relationship between lighting in the workplace and the associated work performance. However, employee involvement increased work motivation and performance across the board [4].

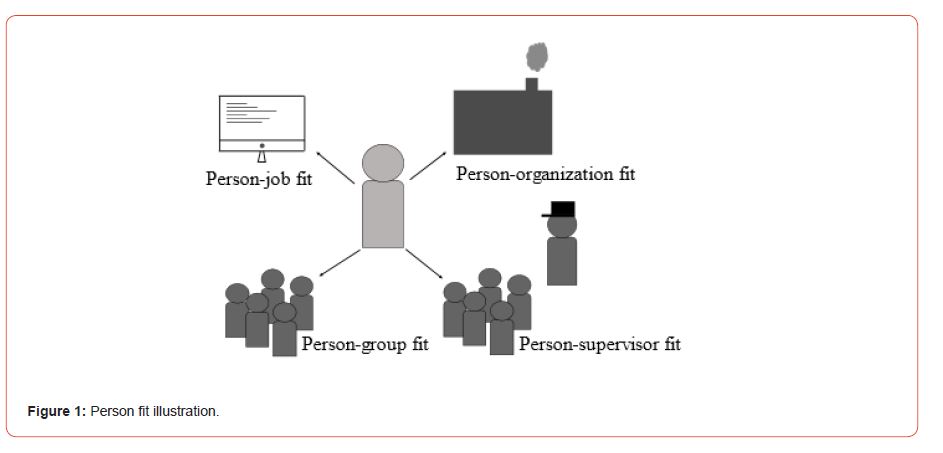

According to Kristof-Brown (2005), the person-fit plays a major role in employee satisfaction. Here, a distinction is made between four areas: person-job fit, person-group fit, person-supervisor fit, and person-organization fit. General job satisfaction is most influenced by the person-job fit. It is defined as the fit between a person’s abilities and the demands of the job or a person’s desires and the tasks of the job. Person-group fit promotes teamwork and satisfaction in a group, which affects the individual employees. The person-supervisor fit describes the fit between a person and the respective manager. The person fit, influences organizational commitment (Figure 1) [5].

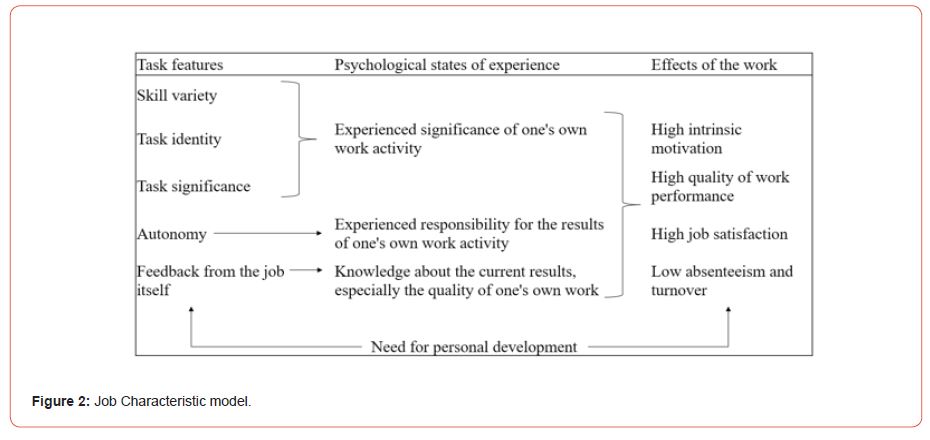

The Job Characteristics Model by Hackman and Oldham from 1980 describes which characteristics of the job are ultimately decisive and via which psychological processes these effects are mediated. According to this model, for work to be satisfying (and intrinsically motivating) it must fulfil three basic psychological requirements: The job must be experienced as meaningful, the workers must feel responsible for the results of their work, and the workers must know the results of their current work, especially its quality.

These psychological states of experience are triggered by five characteristics of the task. These are:

1. Skill variety: the task should not only require a single or few skills of the employees, but as many motor, intellectual and social skills as possible. In this case, they can use different skills and knowledge in the work and, moreover, are not stressed one-sidedly.

2. Task identity: This refers to the degree to which an employee completes a coherent product or a complete service. The opposite is illustrated by simple tasks in which only reduced subtasks are carried out. Holistic tasks convey to employees the meaning and importance of their work.

3. Task significance: This refers to the impact of the task on the lives and work of others: those who recognize how their activity benefits customers, how it relates to the tasks of their colleagues, but also to the work of other departments in the company, will understand their contribution to the goals of the company and thus recognize the importance of their work.

The first three characteristics combined determine whether the activity is experienced as significant, i.e. these characteristics can also compensate each other in their effect. The two remaining characteristics, on the other hand, are to be considered independently.

4. Autonomy: This characteristic is present when employees are able to choose the means of their work on their own responsibility and to set partial goals independently. In this way they experience that they are not without influence and significance, which in turn strengthens their self-esteem and increases their willingness to take on responsibility.

5. And finally, feedback from the job itself, i.e. feedback that is directly inherent in the task. Feedback enables employees to correct mistakes on their own and they always know where they stand on the way to achieving their goals (Figure 2) [6].

One factor that affects employee satisfaction is the behaviour of managers, as Gastil found in 1994. In his meta-analysis, he evaluated studies that dealt with a participative versus authoritarian leadership style: the average correlation was r = 0.23 (positive values indicate a positive correlation between the democratic/cooperative (participative) leadership style and satisfaction. Authoritarian leaders contribute to employees feeling little job satisfaction [7]. In their meta-analysis, Judge et al. found a correlation of r = 0.40 for the relationship between managers’ orientation toward employees and employees’ job satisfaction [8]. The correlation between task orientation and job satisfaction was about half lower. Further leadership style results can be found in the meta-analysis by Judge and Piccolo in 2004 [9]. Here, the extent of laissez-faire-oriented leadership correlates with job satisfaction with ρ = -0.28 after reduction correction for predictor and criterion as well as correction for sample size. In contrast, the relationship between leaders who convincingly perform their role model function and thereby earn trust, respect, appreciation, and loyalty (transformational leadership) and job satisfaction is positive and stronger (ρ = 0.58). This means that both a democratic, cooperative (participative) and a leadership style that is positively oriented toward employees have small to moderate effects on job satisfaction. Transformational leadership has strong positive effects, whereas a leader who does not perform his or her leadership duties is responsible for negative job satisfaction. This negative correlation also applies to the relationship between destructive leadership, i.e. hostile leadership behaviour, and job satisfaction [10].

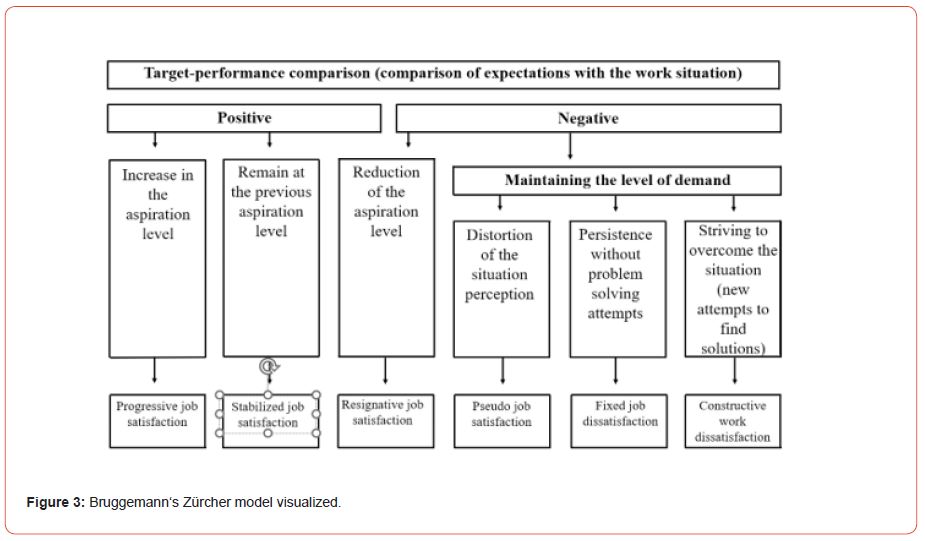

Another look at the topic of job satisfaction is provided by Brüggemann’s Zürcher model from 1976. The model shows various forms of job satisfaction. The starting point is a comparison between one’s own individual needs and expectations (should) and their actual realization in the world of work (is). If the result is negative, the employee tackles it through various strategies (coping strategies). If the demands decrease, however, a kind of resigned job satisfaction develops (it could be worse, the employee is satisfied overall). There is also the possibility that the level of demand is maintained, which in turn distorts the perception of the situation, nothing is done about it, or the employee tries to solve the situation on his own. This results in further forms of job (dis)satisfaction: pseudo job satisfaction, fixed job dissatisfaction, constructive job dissatisfaction. If the target-performance comparison turns out to be positive, the worker can increase or maintain his or her level of aspiration. A stabilized job satisfaction results from the maintenance and a progressive job satisfaction from the increase. While stabilized job satisfaction aims to maintain the status quo, progressive job satisfaction gives rise to new objectives, which in turn can also result in a negative actual-target comparison (Figure 3) [11].

Overall, it is difficult to measure job satisfaction accurately, as many different influencing factors play significant roles. If one decides to measure job satisfaction in different dimensions, then certain aspects of job satisfaction must be selected (selection of aspects of job satisfaction). The various aspects play an important role in the determination of job satisfaction. The subjectivity of reality is important, since everyone interprets job satisfaction differently based on a diffeerent set of values (subjectivity of reality). Well-being and state of mind can also influence judgment (mood and rating). If an employee feels that there is a certain expectation, his response may be different in order to meet the demands and expectations of his counterpart (social desirability). It also happens that the same structures are evaluated individually, for example through experience (subjective structures). No general assessments can be made by closed questions, but only predetermined assessments (availability heuristics). Finally, the employee is dependent on his memories, which does not always lead to answers that are close to reality (reconstruction and rationalization) [12].

Thus, job satisfaction can only be measured in part, but never comprehensively. There will always be areas, circumstances or situations that cannot be considered in the measurement.

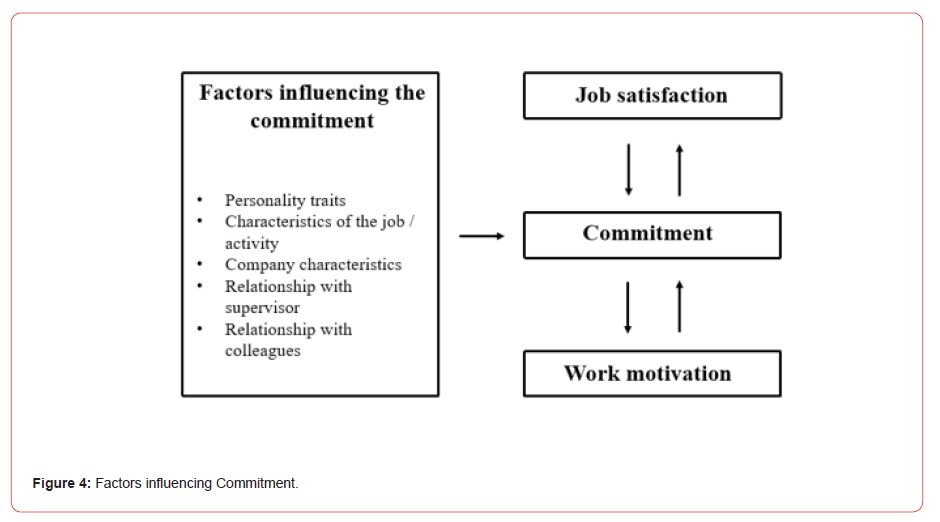

Overview of factors influencing organizational commitment

While job satisfaction is strongly dependent on every-day and fast-moving influencing factors such as superiors or specific working conditions, organizational commitment is oriented toward continuous, permanent conditions. Among other things, this can be illustrated by the higher correlations of organizational commitment to turnover intentions compared to job satisfaction [13]. The influencing factors in general must be divided into two different sections, person-related and work-related factors, which differ in detail [14]. A third feature, organizational characteristics, was included in the construct of organizational commitment by Meyer et al. Person-related and work-related factors influence the layers of affective, normative and, continuance commitment in different ways. All three levels are characterized by their own variables, which in combination describe the relationship of an employee to an organization [15].

By person-related factors we mean, age, marital status, qualification, gender, education, emotional intelligence, and company affiliation [16]. Summed up, they are simply factors describing an individual by its personal characteristics (Figure 4).

Since organizational commitment, as already described in the previous chapters, represents a relationship of the person to an organization, person-related factors provide the framework for this relationship. An individual thus chooses an organization according to the criteria relevant to his or her personal situation in order to enable a long-term relationship. Company affiliation as part of the person-related factors is not only a factor but also the aim of organizational commitment itself. That means that the ability of organizations to influence organizational commitment regarding person-related factors is limited but aim to increase one of them. Since person-related factors cannot be changed, only one of them can be influenced from outside. The qualification of an employee represents a snapshot, which is, however, changeable. As part of human resources, the development of employed people is an element within the concept of organizational commitment.

As opposed to person-related factors, work-related factors are influenceable. Nonetheless, they have the same influence on organizational commitment as person-related factors, as shown in the following figure. Work- related factors describe the environment of an employee inside an organization. Job involvement, general job satisfaction, occupational commitment, job performance and organizational citizenship behavior were defined as antecedents of organizational commitment by Meyer et al. [15]. Furthermore, stress, work-family conflicts, fluctuation, and termination cognitions need to be considered when it comes to beneficial aspects of organizational commitment [17]. The figure as shows that job satisfaction and work motivation are excluded from the collected influencing factors. Although both have a direct effect on the commitment itself, both are enormously correlated with the commitment, so that they must be clearly identified as independent factors. In the course of research on organizational commitment, clear interactions between these fields have already been found. However, these interactions have to be put into perspective, since job satisfaction as well as work motivation can influence organizational commitment. At the same time both can also have a strong impact independently of organizational commitment [15]. This will also be presented in more detail in the following sub-chapter.

Organisational characteristics are not psychological factors, they are also important for long-term commitment. In today’s world, many more aspects than working hours and pay play a major role when it comes to judging employers. It is more about creating a brand of the organization that can be marketed to commit existing talent and potential [18]. Organizational characteristics cannot be distinguished from work-related factors quite as clearly as personal and work-related factors. Although both groups are mentioned in the literature, they are sometimes treated separately and sometimes together. Both, however, deal with the positioning of work-related issues, and thus also with organizational characteristics in terms of their influence on employees. Due to the complexity of organizational commitment and its influencing factors, organizations are forced to develop their organizational commitment strategies in the increasing battle to attract and engage the best professionals.

A tool used in the field of human resources is the employer branding which combines the influencing factors of organizational commitment in one expression [19]. To position themselves in the labour market as the best option for the most valuable employees, companies must design strategies and implement actions that help the company. Therefore, the creation of the employer brand can be seen as a strategy to promote the dimensions of organizational commitment [20]. Employer branding is much more than a human resources tool for generating organizational commitment, but it includes many other issues that can affect individual employees and their organizational commitment. Blasco et al. described the goal of employer branding as developing a bond with employees that is based on the values and goals of the organization, but at the same time are universal but defined by the company. These are based on the active involvement of current employees to improve their motivation and retention. A resulting benefit is committed employees who also act as the best ambassadors for the company [21].

As can be seen, organizational commitment depends on many influencing factors, but all of them only serve to retain employees in the long term. The modern working world, however, this is shaped by another component: mobile working. In the next chapter, we will examine the extent to which mobile working and its variants have an impact on organizational commitment. We will also provide practical examples based on the points mentioned above.

Correlation of job satisfaction and organizational commitment

In the previous subchapters we gave an overview of influencing factors for the exact purpose of job satisfaction and organizational commitment. In this subchapter we will display the correlation between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

While job satisfaction is strongly dependent on every-day and fast-moving influencing factors such as superiors or concrete working conditions, organizational commitment is oriented toward continuous, permanent conditions. Among other things, this can be illustrated by the higher correlations of organizational commitment to turnover intentions compared to job satisfaction [13].

Although job satisfaction and organizational commitment are different concepts, they have a strongly correlated with each other. The meta-analysis shows that the general job satisfaction has the highest influence on affective and normative organizational commitment. Job satisfaction shows the employees response towards the job while organizational commitment is a response to values and goals of the organization [15].

Emotionally attached employees are more motivated to deliver a top performance. A strong bond between the employee and the organization can therefore be achieved through an emotional attachment of the employee to the goals of the organization. Emotional attachment is to be considered independently of the satisfaction of an employee, since also indifferent employees can be satisfied, without identifying themselves with the organization [22]. On the other hand, employees can be unsatisfied with their jobs and at the same time have positive feelings towards the organization, its values, and its objectives [15].

Thiele assumed that a high job satisfaction leads to a strong/ strengthened organizational commitment. That means that the more an employee is satisfied the higher the employees’ organizational commitment is. Although both constructs are linked to one another job satisfaction does not play a decisive role in organizational commitment and vice versa. One analogy between the two constructs is that if an employee has a strong organizational commitment or a high job satisfaction both lead to a higher motivation and less fluctuation which then leads to a higher value of the employee for the company [23]. In another study a moderate to strong connection was found between organizational commitment and job satisfaction stating that job satisfaction leads to organizational commitment [24]. In 2016 study showed a positive relationship between job satisfaction and affective and continuance commitment. The relationship between normative commitment and job satisfaction did not show any significance. The results also showed that there is no difference between job satisfaction and organizational commitment in terms of the employee’s age. The study also showed a difference between male and female employees. The female employees have a slightly lower score (Mn= 3.34) than male employees (Mn= 3.44) [25]. One more assumption is that there is correlation between the two concepts with one not being the result/consequence of the other. This leads to an alternate influence on one another in the sense of a causal chain. Thus, job satisfaction leads to organizational commitment and in return increases the job satisfaction of the employee [13]. Despite many similarities, both constructs should be considered independently. Theoretically, there are two criteria that can be used to distinguish the two constructs: first, stability over time and second, specificity of the reference subject. Thus, job satisfaction exhibits a higher degree of specificity with respect to different situations and conditions and consequently proves to be less stable over time. Job satisfaction differs from organizational commitment, the particular reason for this circumstance is that job satisfaction results from a short-term variable of the current work situation, whereas organizational commitment describes a more stable and long-term commitment [26].

A healthcare professional study has shown that emotional competence tends to correlate with the job satisfaction and organizational commitment. It also concludes that healthcare professionals with emotional competence can remain their organizational commitment unaffected while they deal with dissatisfaction in the workplace [27]. In Northwest Haiti a study was conducted and concluded that there is a strong positive correlation between affective commitment and job satisfaction. A significant relation between total satisfaction and normative commitment was found. They conclude that the higher the employees’ job total satisfaction is, the greater the effective and normative commitment is. Thus, total satisfaction is highly related to the overall commitment [28]. To conclude, one can, say that job satisfaction and organizational commitment are two different concepts. Both concepts have a high correlation to one another and can be seen as co-dependent on each other.

Discussion on mobile working influencing organizational commitment

Mobile working in general is generally considered a positive work condition, but mobile working has not only advantages for organizational commitment, but also disadvantages. These advantages and disadvantages will be presented in this subsection. A 2020 study during the COVID-19 pandemic drew inconclusive conclusions about the impact of mobile working on the productivity of on different workers. In general, the study concludes that mobile working can lead to greater flexibility, higher motivation, and a better work-life balance of the employees. Bao et al. also concluded the importance of recognizing individual differences – if a mobile worker is not very productive the organization needs to offer training for these employees. The results also show that the right resources must be prepared at the beginning of a project in order to reduce the risks of mobile working during a project [29]. In a metaanalysis from 2012 a small but positive correlation between mobile working and organizational commitment was found, although they did not distinguish between the three dimensions of organizational commitment nor the extent of mobile working. Mobile working is believed to increase productivity, ensure employee retention, strengthen organizational commitment, and improve performance within the organization. In other words, it is indeed beneficial for organizations [30].

Another research was done in 2020 by Wang et al. concluding that the affective organizational commitment is negatively influenced by the mobile workers psychological isolation, while the continuance organizational commitment is positively correlated to psychological and physiological isolation. These results indicate that mobile workers remain with their employer du to time, emotional energy, weakened marketability or perceived benefits instead of an emotional connection towards their colleagues and/ or organization [31]. The benefits that were found in 2020 by Boa et al. were again supported in 2021. The results suggest that most employees experience with mobile working was more positive than negative during the COVID-19 pandemic. Three factors represent the main benefits of WFH: Work-life balance, improved work efficiency, and greater work control were the three main benefiting factors of mobile working. Home office constraints, work insecurities, and inadequate work resources were the three main disadvantages from mobile working. Mobile working can have several advantages for both employees and companies. However, mobile working can also have disadvantages for both of them. The way mobile working is implemented plays an important role in balancing out the advantages against the disadvantages. Due to the technological development and its significant advantages, remote work is on the rise. Just like Bao et al. the research emphasizes the importance of recognizing individual differences [32].

In 2021 by Wang et al. challenges of mobile working were identified. There are four challenges: work-home interference, ineffective communication, procrastination, and loneliness. They also concluded that mobile working characteristics relate to employee well-being and performance which then influences organizational commitment. Especially lower levels of mobile working challenges relate positively to social support. Work autonomy is negatively related to loneliness and the workload and supervision lead to a higher work-home interference, while the workload leads to a lower procrastination [33].

In 2022 the results of a study were able to show that mobile working did not have a detrimental effect on the constructs studied, even during the pandemic. When considering the construct work interruption, the quantity (extent of home office) is relevant. However, for the other three work-related constructs of job satisfaction, affective commitment, and social support, it is not the quantity of mobile working that seems to matter, but the quality, in this case the decision to use mobile working. These results demonstrate the importance of the flexible use of mobile working and thus the perceived possibility of deciding for oneself whether to work from home or not [34].

Nevertheless, organizations that structure work in a flexible way in terms of location should consider that each location attracts attention through its special significance, or the behavioral settings found there, for example, by evoking the social category of family in the office at home - despite all the quiet. Therefore, it should not be disregarded that other, possibly rather unconsciously acting identification mechanisms in such environments limit the identification with the organization or even direct it to a different focus. Thus, the results suggest that the more public the work environments are, the more the identification with the organization is impaired by work outside the office. Since in these more public the work environments the physical and social environmental elements/stimuli are less under the control of the individual and are of less identity-relevant significance or symbolism. Offices, on the other hand, focus on organizational commitment through the environmental elements found there, are generally well equipped to enable organizational members to achieve optimal work performance, and contribute to a homogenization of individual and collective attitudes, values, and behaviors in the form of an organizational behavioral setting [35].

Another qualitative study from 2022 showed that the advantages of mobile working that meet the employees’ expectations than lead to a stronger commitment from the employee. The resulting advantages of mobile working are work-family balance, productivity, organization, responsiveness, and organizational commitment [36]. In summary, it can be said that mobile work/ home office brings many advantages to the employees and the organization. Only a few of the many advantages are for example that the employee is offered more flexibility, the work performance is increase and trips to the office can be saved. Nevertheless, it is clear that the disadvantages should not be underestimated, for example loneliness and/ or the general psychological strain is a major challenge. It is also made clear that organizational commitment does not suffer as a result. Generally, mobile working influences organizational commitment.

Comparison of practical mobile working approaches

The topic of mobile working is still relatively young and, as already described in one of the previous chapters, has only received a significant push in the industrialised countries since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020. Before that, the lack of technical possibilities was often a brake on mobile working. If the technical possibility of teleworking existed, however, acquisition and implementation costs were a further obstacle. In addition, the employer feared that it would change the communication and synergy between teams and affect their productivity in terms of too many distractions [37]. The associated loss of control, as well as difficulties in terms of leadership, were a concern in many organisations. Another barrier to mobile working in the early days was security issues related to data protection. Until the beginning of the pandemic, old-fashioned corporate cultures were also a clear obstacle to working outside the company’s premises. One of the first experiments in teleworking was carried out by the Swiss credit institute in 1989. It employed about 65 people in six so-called “work centres” in Switzerland. The results of this experiment were positive in terms of productivity [38]. A conclusion on oranizational commitment is not mentioned in this experiment. Moreover, since the employees worked in rooms provided by the organisation, it can be concluded that many of the previously mentioned obstacles were not relevant. The work centres were more like branches of an organisation.

Another attempt at teleworking was made by Hunton in the USA in 2005. He later described the results of this experiment with Norman, the execution of which was published in the Journal of Information System in 2010. Already at that time, the two outlined that the structure of telework varies from company to company, but most arrangements allow employees to perform their work tasks from different locations. There are many factors in favour of employers considering such arrangements for their employees, for example to motivate them to perform better and to promote commitment to the company. Using data collected during the longitudinal experiment reported in 2005, Hunton and Norman sought to better understand how organisations can achieve these goals by examining the effects of alternative telework arrangements on employees’ organisational commitment and assessing the relationships between telework arrangements, organisational commitment, and task performance. Respondents in 2005 who participated in three of the telework conditions showed significant increases in affective, continuance and normative commitment compared to the control group. However, one of the test groups, working exclusively at home, showed equivalent results with the control group in terms of organizational commitment. Although Hunton and Norman expected that participants with a greater number of work-at-home alternatives would show a greater increase in all three dimensions of organisational commitment, this expectation was only slightly confirmed. They find a positive relationship between organizational commitment and task performance under all treatment conditions in that organizational commitment mediates the relationship between telework arrangements and task performance [39].

Although there have always been experiments or approaches to mobile working as the two in advance, a lot of companies would not have considered working from home for the particular reason that there was no incentive to do so. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the development of companies therefore tended to follow the examples of Silicon Valley, where employees were offered everything at the workplace in order to stay in the facilities as long as possible and to raise the productivity and identification in order to push the organizational commitment of individual employees to a maximum. With the onset of the pandemic, a momentum shift emerged. Companies were forced to rethink and create the conditions for mobile working as quickly as possible due to the regulations to contain the pandemic. Different variants of hybrid working, but also working exclusively from home, became the norm [40]. The classic five-day-a-week on-site job is outdated. High salaries and good jobs and even social benefits like in Silicon Valley are no longer the compensation for long commutes. The hybrid models combine everyday office life with flexible working days from outside. During the Corona pandemic, some organisations relied exclusively on remote working. Others gave their staff the option of working from home part of the week and coming into the office only on a few days. This way, alternating days avoided staff meetings. In addition, with hybrid models, employees did not become too distant from the work environment and, despite the necessary distance, still had a place that connected everyday life with the respective organisation.

However, various studies during and after the pandemic have shown that feared circumstances (e.g. lack of control, descending productivity, descending organizational commitment, etc.) have failed to materialise. On the contrary, employees who work exclusively remotely have been found to be more diligent and productive. This remote working also affects the social component of employees. The biggest challenges remote workers face are loneliness and a poorer work-life balance. Employees who work remotely tend to work longer hours compared to office-based employees. The risk that a person will overwork and be mentally distressed is therefore much more pronounced among remote workers. The mental well-being of a team cannot be underestimated, as burnout can lead to performance problems and cause employees to look for other opportunities [41]. In a study published very shortly before the pandemic, teleworkers’ affective commitment is shown to be negatively related to psychological isolation, while their continuous commitment is positively correlated with both psychological and physical isolation. It can also be inferred that teleworkers stay with their employers because of perceived benefits, such as saving resources and time and emotional energy, or weakened marketability, rather than because of an emotional attachment to their colleagues or company [31]. It can therefore be concluded that a loss of general organizational commitment can result from a too great perceived commitment to the organization (NOC). The practical examples show that the ongoing qualification of employees through mobile working must not be omitted. In particular, older employees must be taken into account, as digital work and communication technologies represent a special challenge [42].

Organizations are therefore faced with the question of how to create an ideal working environment for employees to improve both the performance of the organization (e.g., coordination, knowledge sharing, organizational culture) and individual outcomes (e.g., productivity, satisfaction, well-being, etc.) [43]. The quality of the workplace can also be a part of employer branding to attract, retain, motivate, and engage qualified employees [44]. In addition, physical office space offers more opportunities for events and bonding activities that can improve the company culture. Interpersonal relationships among colleagues are easier to build locally than when people only know each other from afar. Research by Deloitte has shown that a strong workplace culture is important for business success, according to 94% of managers and 88% of employees. So, fostering a corporate culture in a physical office environment is critical to success [45]. As the first wave of the pandemic subsided, the preference for a particular work environment quickly became a plaything of emotions. Employees who were forced by their organizations to return to the office sought new employers in order to continue to enjoy the comforts of working outside the office. The organizations with high churn rates faced an exodus of talent, which combined with other factors led to the great resignation that still haunts companies around the world. Which working model is most effective is still hotly debated two years after the first lockdown. Companies now offer remote and hybrid workplaces as a strategy to retain talent rather than for performance reasons [41].

Critical appraisal and recommendation for action

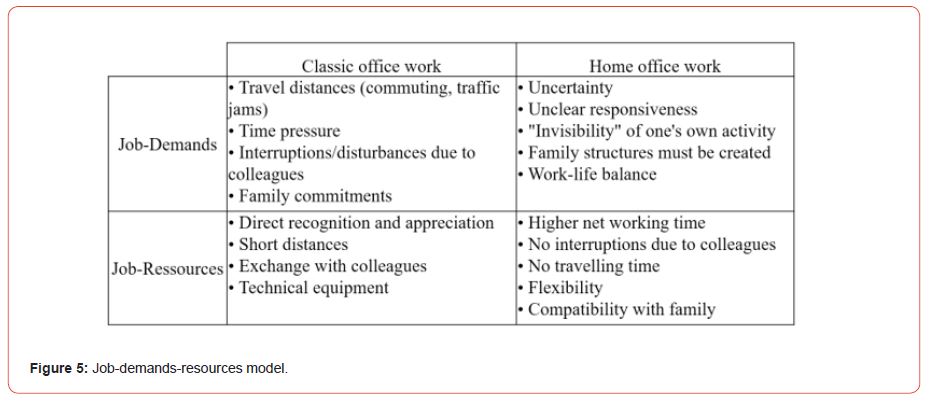

At first glance, one sees many parallels between the discussion and the practical example. The topic COVID-19 has influenced and revolutionized a lot in the field of telework. For the first time, companies were forced to offer their employees this flexibility to keep the company and its daily business running as smoothly as possible. Of course, this has posed a great challenge to many employers and employees alike. Meetings suddenly became video conferences; conversations became emails and events were postponed indefinitely. One model that can be used to illustrate the scope of the shift away from office work to home office work is the job-demands-resources model. This initially assumes that stressful factors (job demands) such as high time pressure, complex tasks or high coordination requirements have a negative impact on employees performance, commitment, satisfaction, well-being and health. However, these adverse effects can be compensated for by the presence of resources (job resources). These include social resources such as support from colleagues but also recognition from the boss, individual promotion, positive feedback from customers and much more. Job demands and job resources should balance each other out to produce positive effects [46]. These points also clearly emerge from the issues previously addressed (Figure 5).

Grunau confirms the aforementioned advantages and disadvantages in a 2019 study. 56% of employees who had already experienced teleworking said they were better able to perform their jobs. 55% said they saw travel time savings as a major advantage. 52% of respondents see work-life balance as a major benefit to telework. In addition to these advantages, however, many employees also report disadvantages. For example, 59% say that working with colleagues is more difficult. 56% of those surveyed said that their work and private lives are mixed. For 54%, the technical prerequisites are not in place. On the part of the employers the flexibility of the employees with 62%, the higher productivity with 45% and likewise the compatibility of occupation and family with 55% are the determining advantages of telework. On the part of the companies, there is a clear picture of what speaks against the introduction of home office. Thus, 90% of the companies state that the main reason is that the job does not allow it. In addition, 22% of companies believe that it is difficult for colleagues to work together. Data protection concerns also come up to 16% [47].

Another point that clearly stands out from the topics elaborated so far is the burden on mental health when working from a home office. Particularly with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large proportion of employees were exposed to complete isolation. Social isolation in general can be associated with various negative mental health consequences such as depression and anxiety disorders for both older and younger people [48].

A clear recommendation for action to prevent psychological harm in isolation is given by Bentley et al. They suggest that social isolation in the context of home office employment is favored when there is insufficient support. In addition to technical support and the trust of management and executives, this support also includes the coordination of activities and collaboration with colleagues. In order to achieve continuous communication in a digitally collaborating team that is conducive to health, it is a good idea to embed regular media-based communication in the work structures, e.g., through virtual team meetings. To counteract a perceived social isolation and positively influence the psychological stress experience of the employees, social and organizational support offers on the part of the company can also be included. For example, depending on the size and structure of the company, it is advisable to provide company support in the event of problems, e.g., through contact persons for challenges relating to virtual teamwork, company social counseling, employee assistance programs, newsletters, psychological and/ or social counseling on work-related topics (e.g., social isolation, short-time work, job insecurity, work-family conflict) [49].

According to Golden and Veiga, organizational commitment suffers when there is a lot of telework. However, with some controlled use of this freedom, commitment increases . As this study dates from 2008, and much has changed since then, this is not confirmed in the previously established facts. With the COVID-19 pandemic, the offer of home office has revolutionized and many companies have been forced to use this method. Many companies were even forced to use it for the first time. Organizational commitment suffered less from telework use during this time, as there were few other options. At least this is reflected in the aforementioned compiled research. In summary, it appears that companies are slowly moving away from the home office, but the possibility of teleworks is firmly embedded in our working behavior due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It has also become apparent that mental health has become a bigger issue, especially due to the social isolation that many employees suddenly and abruptly felt. However, the freedom and flexibility that the introduction of telework has given us should not be underestimated. The work-life balance has increased, and it also shows that there are many parallels between theory and practice, both in terms of the advantages, freedoms, and benefits, but also the disadvantages and dangers of teleworking and organizational commitment.

Conclusion

In the beginning of this paper it we pointed out, that we will focus on the following three questions:

a) How is job satisfaction measured?

b) What influences organizational commitment?

c) How do mobile working models affect job satisfaction and organizational commitment?

Based on our analysis we come to the following conclusions.

There are many different approaches to measure job satisfaction. However, there is not one universally accepted correct way to measure job satisfaction. Due to the complexity of this topic, it does not seem possible to get a full view of all relevant factors. Many factors are subjective and defined differently by different organizations and individuals. In order to answer the question “How is job satisfaction measured?” It is necessary to narrow down the many factors on which the research is focused.

We find different factors being relevant to answer the question “What influences organizational commitment?” During our investigation we found that both, employees and organizations, can influence organizational commitment. But there are factors that are just not influencable due to the fact that they are person related factors and defined by an individual’s character traits. Since organizational commitment has an impact on the performance of a company, it is important to pursue several otions to positively influence organizatiopnal commitment. Employer branding can be a holistic approach to address this issue. However, it constantly needs to be adapted in order to meet the changing requirements of employees.

There clearly is a correlation between job satisfaction and organizational commitment. While both variables can be analyzed separately, they are related to each other. The answer to our third question builds on the answers to the first two questions. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the influencing variables have been examined more closely. Contrary to the assumption that mobile working could lead to a loss of organizational commitment and performance, employees feel much more committed to their employer when working on the move or from home, as they enjoy the resulting advantages and no longer want to do without them. During our investigation, we found that there are few recent metaanalyses on these topics. COVID-19 has changed work habits and mobile working has become more widespread. The traditional 5-day work week in the office is not likely to come back. Companies should strive to make the use of their office space attractive again. Modernizing buildings and infrastructure, upgrading technical equipment and providing benefits for the physical wellbeing can serve this purpose. We assume that there will soon be more research on these changes.

In summary, we found that job satisfaction and organizational commitment are difficult to measure, but can have a major influence on each other. Although there are many studies on these topics, the subject has not been fully explored yet and, due to the constant changes in working behavior, there is an ongoing need for additional research on these issues.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

-

Inez Bijker, Marvin Merken, Yara Werdermann and Nadine Ladnar*. How Mobile Working Impacts Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Cross-Sector Scholarly Literature Review. Iris J of Eco & Buss Manag. 1(2): 2023. IJEBM.MS.ID.000506.

-

Green business management, Customer satisfaction, Environmental sustainability, Communication, Marketing, Advertising campaigns, Products, Services

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.