Research Article

Research Article

Beyond the First Look at the Post-Urban World Paradigm: Innovative Global Economies and Emergent Transformation of Cities & Regions1

Tigran Haas1* and Hans Westlund2

1PhD is the Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Urban Design at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden

2Professor in Regional Planning at KTH, Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, and a Professor in Entrepreneurship at Jönköping International Business School (JIBS), Sweden

Tigran Haas, 1PhD is the Associate Professor of Urban Planning and Urban Design at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden.

Received Date: September 02, 2023; Published Date: September 15, 2023

Abstract

Many global cities and towns have experienced unprecedented economic, social, and spatial structural change in recent decades. Today, we find ourselves between a post-urban and a post-political world, presenting new challenges to our metropolitan regions, municipalities, and cities. Many megacities, declining regions, and towns are experiencing an increase in complex problems regarding internal relationships, governance, and external connections. In particular, a growing disparity exists between socially excluded citizens within declining physical and economic realms and those in thriving geographic areas. This conceptual and analytical paper, which falls in the areas of urban economics, city planning, urbanism, and economic geography, conveys how forces of structural change shape the urban landscape. In this paper, we discuss the Post Urban World Paradigm from different theoretical standpoints and various methodological approaches and perspectives; this is alongside the challenges and new solutions for cities and regions in an interconnected world of global economies. A short reflection is also given on the conceptual clarification of Trans urbanism, Post Urban World & Beyond as well as the important idea and urban phenomenon of Regional Cities. The paper also takes a unique perspective on Social Capital and the Phenomenon of Third (Public) Places in Post-Urban Regions, but not going deeper into the issue. The discussion and position paper are aimed at academic researchers interested in regional development, economic geography, and urban studies and practitioners and policymakers in urban development.

1Corresponding Author*** Dr. Tigran Haas (tigran@kth.se). “A New Perspective on Urban Development” first appeared on the RSA BLOG; Regional Studies Association 2023 | Reg Charity No. 1084165 | Reg. in England and Wales Company No 4116288 | VAT No. 393 7705 16. This paper contains small parts of that article, while this is a new, expanded, and unabridged version. (RSA BLOG portions used by permission of authors Hans Westlund and Tigran Haas, who both work in the Department of Urban and Regional Studies at the KTH Institute of Technology. They recently co-edited the book “In The Post-Urban World Emergent Transformation of Cities and Regions in the Innovative Global Economy”, an internationally peer-reviewed book.

Introduction

The complexities of contemporary global urban, political, economic, and environmental issues are evident. It is not hyperbole to say that human beings are now confronted with the most significant challenge that we have ever faced; in fact, it is a matter of life and death. The planet has recently been experiencing a convergence of natural and man-made crises that are unprecedented in our lifetime. We are also facing the consequences of accelerating and rapid urbanization, the scarcity of natural resources and their mismanagement, the impact of major errors in our responses to disasters, and the increasing demand for and complexity of greatly expanding transportation flows.

In addition, our societies have undergone rapid and radical shifts in age and class, increasing inequities between the rich and poor, and intense demand for affordable and high-quality housing. All of these significant challenges require immediate solutions from architects, urban planners, human geographers, urban economists, regional scientists, urban designers, landscape architects, urbanists, and not least, policymakers; actually, we need the combined efforts of all good people who are concerned with the physical condition and future of our cities. We need these professionals and experts to contribute their most imaginative, pragmatic, resilient, innovative, and just solutions.

Mankind has spent almost its entire history in what we nowadays call the countryside. Cities emerged as small islands in ‘oceans of countryside’ when agriculture had become efficient enough to feed a non-farming population. Except for a few cities with solid management and transportation systems (such as ancient Rome), most cities, by today’s standards, remained small until the Industrial Revolution. It has been estimated that the urbanization rate in the world in 1800 was not more than 3% (Raven et al. 2011). Edward L. Glaeser has pointed out that cities with a million inhabitants before the year 1800 were all capitals of empires, and the reason that they could reach that size is that they were the best-governed cities in the world.

The Industrial Revolution would change the urban-rural balance forever. Industrialization meant urbanization by the growth of existing cities or the emergence of new urban agglomerations. However, urbanization also meant increased demand for rural products, such as food, building materials, firewood, and not most minor raw materials for the new industries. In this way, industrialization also triggered the development of rural areas – but not enough, so for millions of Europeans, emigration to America was the opportunity for a better life.

The industrial crisis of the Western world in the 1970s marked a transformation of the world economy. The old industrial-manufacturing economy took a significant step back, and a new economy, based on the technological shift from mechanical to digital technology, the knowledge economy, started to rise.

The expansion of the knowledge economy is strongly intertwined with the globalization spurred by technological development and political/institutional decisions. On the one hand, the digitalization of banks and the international financial system meant a globalization of the financial sector and that national governments could no longer control financial flows across national boundaries. On the other hand, the economic reforms of China in 1978, the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, and the transformation of the European Economic Community (EEC) to the European Union (EU) in 1993 and its subsequent enlargement were some of the critical political/ institutional steps in the world’s globalization.

The knowledge economy’s integration with globalization has brought enormous changes to the world. This book focuses on one of many aspects of these changes, viz., the transformation of cities in the wake of the global knowledge economy’s breakthrough. This is certainly not the first book that addresses these issues. However, it is the first book that simultaneously addresses cities’ internal spatial transformations and extensions to new types of city regions and their global networks, in Edward Soja’s words, ‘post metropolitan’ regions. Combining these two aspects, we conclude that we are entering a post-urban world.

The industrial crisis of the 1970s was not only a result of rising oil prices but also of the emergence of new competitors in some of the core industries of the western world: steel and engineering industries, including even such an advanced industry as the automotive industry. The breakthrough of the knowledge economy saved the western nations from economic stagnation but did not save all regions from the opposing sides of this transformation. Some cities and regions were winners, and some were losers. However, at national levels the breakthrough of the knowledge economy was strong enough to prevent protectionist policies in favor of the declining sectors. This opened for the rapid industrialization of China and other developing countries – and with that, the most rapid urbanization that the world had experienced. (It should be underlined that the current, rapid urbanization of developing countries not only is caused by industrialization).

Post Urban World Paradigm Features

A first feature of the post-urban world is that while the crisis of the 1970s was accompanied by counter urbanization in many of the developed countries [3,8], the following decades have mainly been characterized by re-urbanization. In contrast to the traditional urbanization that consisted of migration from countryside to cities (and often within the same region) this re-urbanization of the western world has been based on other sources:

a. migration from declining manufacturing cities and regions to expanding knowledge- and service sector cities and regions – or from the centers of declining manufacturing cities to suburbs;

b. upward migration within the national urban hierarchies, i.e., from smaller urban settlements to bigger ones, and;

c. increasingly, on immigration from low-income, or war affected countries.

Another strong tendency in the current wave of urbanization is densification of city regions, in particular densification of suburbs. Edward Soja discussed the transformation of big cities from dense centers with sprawling low-density suburbs, to polycentric city regions with relatively high density all over. “Where this process is most pronounced, the longstanding urban-suburban dualism of metropolitan urbanization has almost disappeared, as the age of mass suburbanization shifts to one of mass regional urbanization, a filling in so to speak, of the entire metropolitan area” [33]. The result is according to Soja a ‘Post metropolitan’ region; a new spatial framework in which the idea of place is weakened and the limit between what is urban and what is non-urban are blurred and tend to dissolve.

A third important trend is the ‘region enlargement’ in the form of spatial extensions of labor markets due to improved transportation infrastructure and public transportation, among others in the form of upgraded and more frequent commuter trains. This enhancement of the transportation infrastructure and its traffic has contributed to the abovementioned densification of the suburbs and extended commuter traffic and thus, larger labor markets. This means that the city regions have not only been densified within a given area, but also ‘sparsified’ when more distant centers (and their suburbs and adjacent rural areas) have become integrated in the metropolitan transportation networks.

The fourth and last trend of the emerging post-urban world that we want to highlight is the downgrading of the relations between city regions and their hinterlands and the upgrading of their networks to other city regions that has emerged with the expansion of the knowledge economy. One of the most important differences between the knowledge economy and its predecessor is that human capital has replaced raw materials and physical capital as the primary production and location factors. City regions’ large, diversified labor markets have become a key location factor for both businesses and labor. The more peripheral cities, towns, and rural areas suffer of a lack of sufficient concentrations of the now most important production factor, human capital, which means that their labor markets remain small and the knowledge economy has difficulties developing there. With the decreased relative importance of raw materials, these areas have less and less to offer the city regions. Instead, the city regions’ exchange mainly takes place with other city regions, whose import and export markets are much larger than those of their peripheral hinterlands. From the countryside’s perspective, this means a division into two parts: one cityclose part being integrated into the extended city regions and one peripheral part that is less and less needed in the knowledge economy. These changes are expressions of that neither the city nor the countryside is what it was and that a stage that we can call post-urban has occurred (Figure 1).

The four features of the post-urban world sketched above are expressions of the dissolution of two dichotomies that have formed much of our thinking on urban development: the urban-rural dichotomy and the urban-suburban dichotomy. These dichotomies were based on the well-grounded perception that the urban fundamentally differed from the rural and the sub-urban, respectively. This is no longer the case. The emergence of city regions where small towns, as well as rural and natural areas, are included, while other, more peripheral rural areas and smaller cities end outside the positive influence fields and gradually fade away, means that the traditional urban-rural dichotomy is being dissolved. The emergence of densified, multinuclear city regions also signals that the dichotomy between dense city centers and sparse suburbs withers. Edward Soja has denominated This latter process as ‘post metropolitan’. Together, these two processes have formed the base for the post-urban world.

Post-Urban World in the Wake of the “New Paradigm Agenda”

Many authors point to a major urban transition underway in Saudi Arabia and around the world – what has been described by various authors as a so-called “new paradigm” (e.g., see Clos, Sennett, Sassen and Burdett, “The Quito Papers,” 2018. Authors note that the process was already well underway before the pandemic, but the disruptions of this period have given it a new impetus. At the same time, the pandemic has revealed the extent of the often- hidden problems created by the previous paradigm.

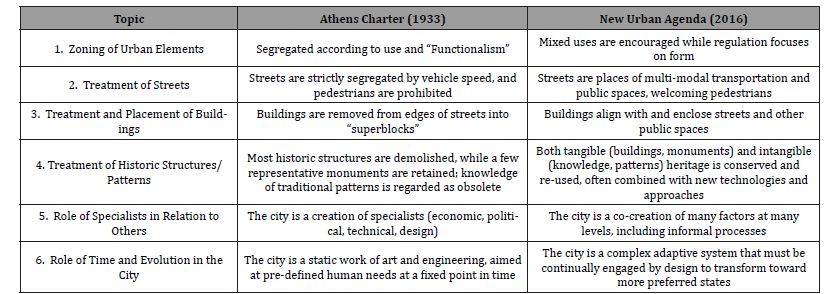

This “old paradigm” – still very much the dominant one – is the late 20th-century model of auto-centric planning, with a lower priority on walkable public spaces and a mix of uses. The new paradigm emphasizes walkability, the human scale, and a re-conception of public space as a continuously walkable, well-connected network or fabric rather than a collection of individual drive-to destinations. More specifically, the “old paradigm” has been described (e.g. in an analysis by [21]) as featuring six key characteristics: segregated zoning by use, segregation of automobiles onto functionally classified roadways, buildings floating loosely within superblock systems, large-scale demolition of historical patterns and structures, the city as technically determined creation of specialists, and the city as a static structure designed to meet fixed human needs that are technically deterministic. These features were described in detail in the Athens Charter of 1933, published later by the architect Le Corbusier. One of the clearest articulations of the “new paradigm” is in the New Urban Agenda, the outcome document of the Habitat III conference in 2016, later adopted by acclamation by all 193 member States of the United Nations. It contains language very much in contrast with the Athens Charter. Instead of segregated zoning by use, the city contains a mix of uses at the scale of neighborhoods, blocks, and even buildings. Instead of segregating automobiles onto functionally classified roadways, the city mixes pedestrians and vehicles, prioritizing pedestrians, and bicycles. Instead of buildings floating loosely within superblock systems, streets, and public spaces are lined with buildings with active ground-floor uses that open to the public spaces. Instead of large-scale demolition of historic patterns and structures, the city’s history (and of its natural environment) is preserved and built upon, with the regeneration of patterns and structures. Instead of the city as a technically determined creation of specialists, the city is coproduced with the residents and stakeholders, including many institutions and individuals acting at various subsidiary scales of space and time. Finally, instead of the city being conceived as a static structure designed to meet fixed human needs that are technically deterministic, the city is seen as a complex evolutionary structure, and design interventions are meant to guide and enhance, not suppress, this natural evolution. A summary of these six points of divergence is included below (Table 1).

Table 1: Key characteristics of the Athens Charter of 1933, and the New Urban Agenda of 2016.

The New Urban Agenda is certainly a landmark in the history of urbanism, with its unprecedented formal adoption as urbanization policy by all 193 countries of the United Nations. Yet in many ways, it describes changes already underway in many Saudi cities: a greater focus on human needs and “humanization”; embrace of mixed-use, with zoning more focused on form; a new emphasis on livability, walkability, and urban greening; a commitment to creating better-quality public spaces, including streets, with a better alignment of active building fronts framing their edges; better use of historic resources, structures and patterns, which, since they have already endured, are more likely to endure into the future; and the involvement of stakeholders and other collaborators as co-producers of an evolving, dynamic city structure.

The common denominator that gives cities its decisive prowess is its ability to concentrate people; this is because the convenience of proximity benefits all, allowing the city to thrive by bringing people and ideas together. However, if gone unmanaged, cities can lose out to the ‘demons of density’, paradoxically giving rise to negative consequences of urban concentration [13]. The advent of rapid globalization and rapid urban growth has initiated a process of urban transformation, posing new challenges for planning, and managing cities. As cities grow, the lack of infrastructure, open spaces, and public amenities begin to undermine the well-being of its inhabitants. Thus, as new cities and conurbations emerge globally, and older ones grow or decay in urban prosperity or urban blight, it is imperative that we be thoughtful in planning and designing their futures. The cities that will do best in the future will be those that capsulize the public realm and the people who utilize these places. This is because public spaces have the potential to systematically support a complex agenda of livability and sociability, economic prosperity, community cohesion and overall sustainability for cities. The inclusion of public space in the New Urban Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals is a welcomed shift towards improving quality of life in cities. In doing so, it encourages urban planners and decision makers to shifts away from the natural tendency of viewing the city as an assemblage of urban infrastructure, to instead focusing on building integrated and holistic cities that deliver the experiences and interactions desired by its citizenry. However, success will not be achieved on its own.

As elements of the New Urban Agenda are cemented into urban plans, strategies, and frameworks around the globe, it will take bold leadership from elected officials and the public to realize the true value of public space as a tool capable of defining the city’s image. Cities, both in the north and south, have fallen short in dealing with the most burning problems of our society and also recent critical transformations in the becoming: those of mass and hyper immigrations, financial crisis, breakdown of the traditional industries, globalization and more. They cannot fall short or fail on the public space agenda. Therefore, those cities currently experiencing rapid urban growth need to be thoughtful in how they deal with public assets and amenities; those that do not plan ahead will find the public realm under serious threat. Thus a need to encourage national and local governments need to establish legislation, policies, norms, and best practices that enable a public space agenda to thrive and thus promote a holistic and integrated approach to planning and designing cities [2]. Unlike other infrastructure, public spaces afford a human element to the city, allowing residents to improve their health, prosperity, and quality of life and enrich their social relations and cultural understanding. Although critical decisions have already been taken in the policy arenas of 2015 and 2016, the future of cities is still in the hands of the stakeholders. Any attempt to establish a public space agenda that does not place the citizens at the center of it will face severe constraints in their attempt to build livable cities.

Post Urban World & Beyond: Post and -or Transurbanism Geographies

Post does not mean anything more than something undergoing rapid change with an unknown destination and uncertain outcome. The prefix “post-” is derived from Latin and is commonly used in English to indicate a position or state that comes after or follows something else. It signifies a shift, a departure, or a movement beyond a particular phase or era.

“Post-” often suggests a break from traditional or established norms, ideas, or practices when applied to various contexts. It implies recognizing that the previous state or condition has been surpassed or that new perspectives, developments, or challenges have emerged. It can also signify a critical examination and reflection on what came before. For example, in cultural and intellectual movements, the prefix “post-” is frequently used to describe a departure from a specific movement or school of thought. For instance, “postmodernism” refers to a departure from modernism and its principles, embracing a more fragmented, self-aware, and skeptical approach to art, literature, architecture, and philosophy. Similarly, “postcolonialism” reflects a period or discourse that emerged after the end of colonial rule. It examines colonialism’s legacies, power dynamics, and cultural implications in formerly colonized societies.

The prefix “post-” is derived from the Latin word “post,” which means “after” or “beyond.” The prefix “post-” indicates a subsequent stage, period, or development that follows or goes beyond a particular concept, movement, or era. It suggests a shift, a departure, or an evolution from what came before. When used with a particular concept or movement, “post-” typically implies a critical reflection or response to the ideas and practices associated with that concept or movement. It suggests a departure from traditional approaches and exploring new perspectives, theories, or practices that emerge after the initial phase.

For example, we often encounter terms like “postmodernism,” “postcolonialism,” or “post-industrialism.” In each case, the prefix “post-” indicates a departure from the dominant ideas and structures of modernism, colonialism, or industrialism, respectively. It represents a critical reevaluation and a recognition of the limitations or shortcomings of those earlier paradigms, leading to the exploration of alternative theories, approaches, or worldviews. “Post-” does not necessarily imply a complete rejection or abandonment of the preceding ideas or movements. Instead, it signifies a recognition that new developments, complexities, or challenges have emerged and that a fresh perspective or framework is needed to address them. In summary, the prefix “post-” represents a subsequent stage or development that goes beyond a particular concept, movement, or era. It suggests a departure from the past and exploring new perspectives, theories, or practices that emerge after the initial phase. The term “post-urban world” refers to a hypothetical future or a conceptual framework that envisions a significant transformation like urban environments. It suggests a departure from traditional notions of urbanism and explores alternative forms of human settlement and spatial organization.

In a post-urban world, there may be a shift from dense, centralized cities to more dispersed, decentralized forms of habitation. Technological advancements, changes in work patterns, environmental considerations, or social dynamics could drive this. The concept of a post-urban world recognizes the challenges and limitations of traditional urbanism, such as congestion, pollution, inequality, and social isolation. It imagines new models of urban living that prioritize sustainability, livability, and resilience.

Post-urbanism often emphasizes the integration of nature into urban areas, the creation of green spaces, and the promotion of walkability and public transportation. It may also embrace concepts like mixed-use developments, smart cities, and digital connectivity to enhance the quality of life. Moreover, a post-urban world may involve reimagining social and economic structures, focusing on local self-sufficiency, community empowerment, and cultural diversity. It’s important to note that the term “post-urban world” is not a concrete reality but a conceptual framework that stimulates thinking about the future of urban environments. It encourages discussions about alternative urban models and strategies to address the complex challenges of urbanization in the 21st century.

Urbanization, Regional Cities, Cultural Urbanism, Compact Neighborhoods – Macro, Meso & Micro

Urbanization and growth of cities work threefold: natural population growth, inward migration, and spatial expansion and consolidation incorporating peri-urban or rural populations. Cities have always been the most critical places for cross-cultural connections and local and long-distance trade, incubators, and transfer grounds of innovation. There is a strong belief that culture can become a launch base for the city’s development and sustainable urbanization - from an economic and social point of view, a foundation for its competitive recovery. In essence, the city is a culture. The fact that culture today is once again a center and a driving force for development is no surprise. Urbanism is not a monolithic term but complex, diverse, and centrally located in history. The aspect of urbanism that reflects the local culture and encourages social interface we can call “Cultural Urbanism” – i.e., culturally and regionally authentic places. Cities are fundamentally social forms, not necessarily built forms. City-making is a social process and the intricate and close relationship between urban environments’ social and physical shaping and the local and regional.

So, there is no question that we live in “regional cities” in “regional places”. Our economies are regional, not statewide, national, or just local. That is why one part of a state or nation can succeed economically while others can fail. There is a local dimension, but in fact, it is the region that functions in the global economic and cultural landscape. Culture is the software of the cities in the same way as the built environment is its hardware. So, urbanism and urbanization coupled with culture is essential to create valuable places where each place is unique and where there is a universal human trait that sets the essential DNA of those hit-filled, innovative, fair, and creative cities: the human scale, diverse decisiveness, and social interaction [5].

The issues of culture and contextualized urbanity seem to be an unavoidable element. Suppose we see the city as the spatial product and the product of social processes, the kinetic and static elements coming together. In that case, the rising paradigm of cultural urbanism becomes even more pivotal in the city’s struggle for just and all-inclusive gendered spaces. Cultural urbanism is an approach that has seven major elements: of paying attention to the context and history of the place as well as narratives, understanding the local preferences of all inhabitants, one which allows for a diversity of users and uses, providing a variety of products, taking a chance to be different in space and place, establishing high-quality open space and public realms and one that creates higher real estate value because of all the above [22].

Urbanization has most substantial impacts on the environment and ecology around us. Environmental impacts are felt regionally, not city by city or neighborhood by neighborhood. Air and water pollution do not stop when they cross a municipality and local, city line. Open (green) urban space systems and wildlife and nature do not obey the arbitrary boundaries we have created in our cities. So, when we come to urban and natural conservation, we can’t continue to do it piecemeal; we’re forced to think regionally. Socially we live in a regional world. As important as it is to have neighborhoods that are coherent and walkable, our social lives, our cultural and civic lives operate at a regional scale. City-making is a social process, but the idea that city fabric is one of the ways by which social, economic, legal processes become real in space and time. Also, it is not simply that (urban) infrastructure deployment in cities produces and reproduces conditions of living, but that it may be constituted, in many instances, by real, living humans, which brings us to three main issues concerning cities and urbanism as a way of life (in the spirit of Louis Wirth): size, density, diversity [38]. The most important one is that of density, which brings us back to the notion of culture again; the point about cities, pace Wirth, is not simply that they contain many people and that they tend to pack them tightly, but that they support and intensify social, economic, and cultural heterogeneity. That is where cultural urbanism starts to play a role as “Cityism” (could be urbanity or publicness or similar) – which means the availability of space for unpredicted social practices [35].

The link between urban society (urbanization), culture, public space, and planning approaches becomes essential in understanding the complexity of urban transformation in the city and its public and private realms [1]. As we celebrate our local and regional differences and build environments that promote community interaction, we should also see what makes our cities unique and exciting and create genuine and authentic places. Sustainable urbanization – functioning built environments and urban networks are only possible when we think, plan, and design systems on a regional city level. These systems incorporate social and economic life, urban politics, culture, and arts. We see research “lacunas” that need to be investigated. In that sense, our proposal is for significant research questions in future studies: To determine the main factors that affect urbanization towards social and cultural changes among different municipalities and the effects that regional city might have on neighborhood’s urban and social fabric; second, to investigate the main attributes that give the positive or negative impact towards urbanization using size, density, diversity in measuring successful cultural landscapes and urban economies at the local scale. Third, to identify whether urbanization impacts social and cultural changes among different actors on the ground and the differences between those that see their localities as part of the regional network regarding the economy, social changes, and culture and those that do not. Finally, fourth, to theorize if urbanization and urban environments that face ever-increasing flows of human movement and an accelerated frequency of natural disasters and iterative economic crises can dictate capital allocation toward the physical components of cities (Figure 2).

A Regional City is not a novel concept. The small, one-dimensional town Sinclair Lewis painted on Main Street disappeared from the American (urban) landscape as he wrote it 80 years ago [20]. At least a century ago, as emerging hubs of the industrial economy, New York, Chicago, and other cities grew to abnormal sizes, the concept of a “metropolis”—a big and complex urban environment— was first proposed [5]. Since then, our metropolitan areas have grown consistently more significant. Metropolitan life throughout the urban regions now rests on a new foundation of economic, ecological, and social patterns, all operating in unprecedented fashion at a regional scale [5,18]. We now live in a regional cocurated metropolitan world clustered with regional cities. A regional city is a central urban hub within a larger region, offering various services and opportunities. Regionalism is an approach that recognizes and supports the distinctiveness of different regions within a larger geopolitical entity, promoting local decision-making, cooperation, and equitable development. In our discussions and meeting with Peter Calthorpe, he explains, as he does in his books [5]. The Regional City, Planning for the end of [9]. Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change, Island Press: Washington DC):

‘There is no question in my mind that we live in regional cities, in regional places. Our economies are regional, not statewide or national. There is a local dimension, but in fact, it is the region that functions in the global economic landscape. Environmental impacts are felt regionally, not city by city. Air pollution and water pollution do not stop when they cross a jurisdictional line. Open space systems and wildlife do not obey our created arbitrary boundaries. So, when we come to conservation, we cannot continue to do it piecemeal; we are forced to think regionally. Finally, I think socially, we live in a regional world. As important as it is to have coherent and walkable neighborhoods, our social, cultural, and civic lives operate at a regional scale. And yet, we do not have regional governance. It is as if we have a blind spot.’

The metropolitan area has become the fundamental building component of this new regional economic system since the conclusion of WWII and the Cold War, as our economy’s globalization, regionalization, and glocalization have accelerated. In the modern global economy of the post-urban world, we discuss regions and regional cities as their spearheads rather than nations competing for global economic domination. Additionally, we have made rapid advancements in our understanding of (urban) ecology due to our realization that the region is the ecosystem’s fundamental unit [5,15]. When we think of neighborhood and public spaces on the micro level, we need, in parallel, to think of city districts on the meso level and regional cities and landscapes on the macro level, i.e., any changes or transformations on the micro or meso level will have direct consequences on the macro level and vice versa. Peter Calthorpe and Joe Fulton contribute to regional cities by advocating for sustainable, walkable, and well-connected urban environments. Calthorpe emphasizes transit-oriented development and mixeduse planning, while Fulton focuses on the specific urban planning model known as the “fused grid.” Both approaches seek to create regional cities prioritizing environmental sustainability, accessibility, and quality of life.

Social Capital and the Phenomenon of Third (Public) Places in Post-Urban Regions

Introduction

The theoretical base of this paper is the hypothesis of the post-urban world (Haas and Westlund, 2018) that underscores the decisive role of city regions for sustainable development and growth and the hypothesis of the regional city [5] that stresses the metropolization of cities. We assume that by integrating concepts of the economic region, the ecological region, and the social region, with an understanding of the spatiality and uniqueness of each physical context, there might emerge a new paradigm for understanding regions and places that thrive and are rich in social capital and those that not. Rapid urban growth in many developing countries worldwide is one of today’s most significant challenges. If managed well, it presents opportunities for development and improved livelihoods; however, if gone unmanaged, the pace and scale of urban growth can outstrip the capacity of local governments to provide essential basic services (water and sewerage) and improved quality of life (urban amenities) for their citizens. Considering these challenges, interventions are often directed towards the supply of physical infrastructure (housing, hospitals, sewer, water, etc.), with little emphasis on improving the social fabric of cities (safety, culture, heritage, public space, etc.). However, recently, a notable shift has occurred in which issues about quality of life have gained recognition. This is best characterized by including a public space agenda in several global processes (Habitat III & SDGs). Social Capital and the Phenomenon of Third (Public) Places in Post-Urban Regions [10].

The phenomenon of third places, public places that allow for the accumulation of social capital in urban neighborhoods and city districts, has been discussed. Social capital is about the value of social networks, bonding people of similar interests and bridging diverse people with norms of reciprocity. Social capital is fundamentally about how people interact with each other. If third places are enabled and exist, then such capital could flourish and be a cornerstone of a viable community or city [25,16]. For a long time, it has been claimed that third places are essential for civil society, democracy, civic engagement, and establishing feelings of a sense of place and that the interaction between physical form and social capital is critical – but the empirical evidence has been weak and consisted of scattered examples and anecdotes [37]. Communities include things held in common, like government and social structure and a shared sense of place or location. The primary function of the community (local community-Gemeinschaft) is to mediate between the individual and society (Gesellschaft), and that people could relate to their societies through both geographic and non-geographic substructures of communities [17].

The third place is an outcry for the return to the fundamental values of a community, some of which have been forgotten and erased in today’s age of fast changes, superficial values, and eradicated places. The popularity of a place where new social networks are built and old ones maintained can never be made obsolete. Third places have existed for hundreds of years. They were places that had appeal and were symbols and active mediators in community communication (Figure 3). As Oldenburg calls them, social condensers places, agoras if you will, where all citizens of the community or a neighborhood meet to develop the place where citizens of a community or neighborhood meet to develop friendships, discuss issues, and interact (social changes, positive and negative ones alike [25]. A well-functioning public realm with a third-place richness can build social capital by enforcing and melding social relations [28]. This happens through in-continuo social contact among people in multiple overlapping role relationships [19].

These third places are crucial to a community for several reasons. They are, firstly, distinctive informal gathering places; secondly, they make the citizen feel at home; thirdly, they nourish relationships and diversity of human contact; fourthly, they help create a sense of place and community, and they invoke a sense of civic pride [26]. The critical ingredient lies in the fact that they are socially binding, encouraging sociability simultaneously and fighting against isolation. They make life more joyous and colorful, enriching the city’s economic activity, public life, and democracy. The life of third places in coffee shops, cafés, hair salons, restaurants, bakeries, semi-informal meeting places, bazaars, other markets, gardens, etc., are in alignment with the argument that these types of places are the facilitators of vibrant and good public life and that in most cases they are in synergy with open public spaces, like squares, bazaars, and other markets [16]. Oldenburg points at the essential ingredients for a well-functioning third place [25]: 1. They must be free or relatively inexpensive to enter and to purchase food and drinks. They must be highly accessible; ideally, one should be able to get there by foot from one’s home; Several people can be expected to be there daily; All people should feel welcome, regardless of their race, gender, or religion, and it should be easy to get into a conversation. A person who goes there should be able to find old and new friends each time they visit. Third places are retreats into social spaces from a selfish need with those of like mind. It’s where we foster some of our self-esteem and a great deal of our social capital that helps us survive and bridge home and work [27]. Coupled with is dignified, affordable and livable housing but in the network of sustainable neighborhoods. The most basic building block for good urbanism is walkable neighborhoods, places where children can get around without having their parents drive them everywhere, where elderly people could live without needing to own a car, where just about anybody could walk down the street to do something interesting and useful. But that walkable neighborhood is just the building block. There’s got to be a larger framework. And that’s regional design and regional planning [6,9,32,34,11].

Conclusions and Discussion

Aside from these features of the post-urban world, some of the leading ideas and discussions in the Urban-Global-Age of development have and are still associated with cities: The concept of global cities [30] Rise of the creative class [12], The network society [7], city of bits [23] and ultimately the Triumph of the city [13] Infinite suburbia [4] and Well-tempered city [29]. These discourses see many structural transformations and emerging patterns in place, happening, or in the continuous ‘becoming’. Creativity is becoming a more critical part of the economy as cities hinge on creative people, i.e., they need to attract creative people’s human capital, which generates growth, and therefore, the cities are engines of growth and economic prosperity when they exemplify this “creativity”. We are witnessing a significant flow of social and economic dynamics of the information age, virtual places and physical ones, and interconnection using telecommunication links as well as by pedestrian circulation and mechanized transportation systems. The new network society becomes structured around networks instead of individual actors and works through a constant flow of information through technology. This is closely connected to the ongoing miniaturization of electronics, the commodification of bits, and the growing domination of software over materialized form. The emphasis on the formation of cross-border dynamics through which cities begin to form strategic transnational networks is seen in the case of global cities; the dynamics and processes that get territorialized are global. Celebrating the city becomes an impassioned argument; the city’s importance and splendor, humanity’s most incredible creation and our best hope for the future, is bestowed with a vital role in addressing the critical issues in these challenging and crises- ridden times. Ultimately, the cities will be battlegrounds where the twenty-first century’s environmental, economic, political, and social challenges will be addressed and ultimately fought (or lost).

The value of creating social capital through public space and its funnel, the third place, is of extreme importance in creating values and benefits for community cohesion. The third place (surroundings separate from home and work) is essential for civil society, democracy, civic engagement, and establishing a sense of place [25]. While home (the first place) is private and work (the second place) offers a structured social experience, third places are more relaxed public environments where people can meet and interact in various ways. The third place, “label,” can be applied to various social spaces, but for many, the most prominent example is the coffee shop: a friendly, informal meeting place to catch up with friends and even meet new people. Another crucial element, one we did not mention here, is cultural heritage management in the post-urban world - a cultural preservation approach emphasizing built environment, citizen input, local character and history, narratives, memories, and sense and image of the place – tangible and intangible elements and assets is needed and opens doors for economic incubation to happen [14]. Finally, the importance of economic exchange for public goods cannot be underestimated - good public space has proven to attract investment, increase property values, generate municipal revenues, and provide economic interaction and improved livelihoods [10].

The post-urban world can also be deducted from a philosophical framework. The transformation of the urban-rural relations can be described in a Hegelian dialectical framework, in which an antithesis meets a thesis, and the two eventually are transformed into something new and ‘higher’: a synthesis.2 In this framework, the rural forms the original thesis, and the urban emerges as the antithesis. Over the centuries, the rural thesis and the urban antithesis have acted as the two main poles of spatial interaction. The Industrial Revolution meant a substantial balance shift between the two poles in favor of the urban. With

Foot Notes2The German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831) is generally seen as the father of this framework. It has been claimed that Hegel considered the thesis-antithesis-synthesis framework a “lifeless schema” and that he did not use it in his works. Instead, the framework should have come from Kant and Fichte (Mueller 1958). However, this claim does not seem to have been accepted by the mainstream interpretations of Hegel’s dialectics.

work, the rural forms the original thesis, and the urban emerges as the antithesis. Over the centuries, the rural thesis and the urban antithesis have acted as the two main poles of spatial interaction. The Industrial Revolution meant a substantial balance shift between the two poles in favor of the urban. With the emergence of the knowledge economy, a synthesis has arisen: the big cities have incorporated surrounding towns and countryside and transformed them into parts of multifunctional city regions that are connected by global city networks. Outside are the remote parts of the former hinterlands that, in the words of Lefebvre (1970/2003, p. 3), slowly “are given over to nature.” The urban-rural dichotomy has ceased to exist, and a synthesis has emerged where neither the city nor the countryside is what they were. A world with these new spatial relations is a Post-Urban World.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

-

Tigran Haas* and Hans Westlund. Beyond the First Look at the Post-Urban World Paradigm: Innovative Global Economies and Emergent Transformation of Cities & Regions. Iris J of Eco & Buss Manag. 1(4): 2023. IJEBM.MS.ID.000519.

-

Metropolitan regions, Municipalities, Cities, Many megacities, Declining regions, Global economies, Trans urbanism, Economic geography, Regional development, Global urban, Political, policymakers, Architects, Urban planners, Human geographers, Urban economists, Regional scientists, Urban designers, Landscape architects, Urbanists

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Post Urban World Paradigm Features

- Post-Urban World in the Wake of the “New Paradigm Agenda”

- Post Urban World & Beyond: Post and -or Transurbanism Geographies

- Urbanization, Regional Cities, Cultural Urbanism, Compact Neighborhoods – Macro, Meso & Micro

- Social Capital and the Phenomenon of Third (Public) Places in Post-Urban Regions

- Conclusions and Discussion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interest

- References