Research Article

Research Article

Beyond the Aggregate: Uneven Development and Target Policies for Native American Reservations

Giuliana Campanelli Andreopoulos1*, and Alexandros Panayides2

*1Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, Finance and Global Business, William Paterson University, New Jersey, USA

2Professor of Finance and Economics, Department of Economics, Finance and Global Business, Cotsakos College of Business, William Paterson University, New Jersey, USA

Giuliana Campanelli Andreopoulos, Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, Finance and Global Business, William Paterson University, New Jersey, USA

Received Date:August 14, 2025; Published Date:August 25, 2025

Abstract

Native Americans remain the most socioeconomically marginalized population in the United States, persistently ranking lowest across key indicators of development. While existing scholarships and policy discourse have examined socio-economic disparities affecting this population extensively, much of the analysis relies on aggregated data and broad national policy frameworks, thereby obscuring substantial variation across communities. The scope of this investigation is to determine whether disparities exist between reservations and based on these findings, to propose targeted policy interventions aimed at fostering more equitable development within Native American communities.

Keywords:Native americans; uneven development; target policies

Introduction

American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) populations continue to experience disproportionately elevated levels of social and economic disadvantage relative to other demographic groups within the United States. The existing literature on AIAN communities largely adopts an aggregated perspective, frequently attributing underdevelopment to institutional constraints - most notably, the historical and ongoing role of the U.S. federal government as both custodian and administrator of tribal lands. While the distinctive land tenure system constitutes a significant structural impediment, this study seeks to move beyond aggregate analyses by undertaking a disaggregated examination of AIAN community development. In so doing, it highlights the socio-economic differences within these communities, examines their underlying causes, and emphasizes the necessity of targeted policy approaches to promote more equitable and context-specific development outcomes.

This paper is structured as follows:

a) Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of socioeconomic development in Native American communities at the aggregate level.

b) Section 3 shifts the analytical focus to a disaggregated examination, exploring variations in developmental outcomesacross selected reservations and analyzing their principal causal factors.

c) Section 4 evaluates the role of the federal government in facilitating development within specific reservations and proposes targeted policy interventions aimed at advancing more equitable development.

d) Section 5 concludes by summarizing the key findings.

What does the aggregate picture reveal?

This section analyzes the socio-economic development of Native American communities in recent years through the lens of established development indicators. The scope of the investigation is to assess the degree of progress achieved by these communities in comparison both to national trends and to other major racial and ethnic groups within the United States.

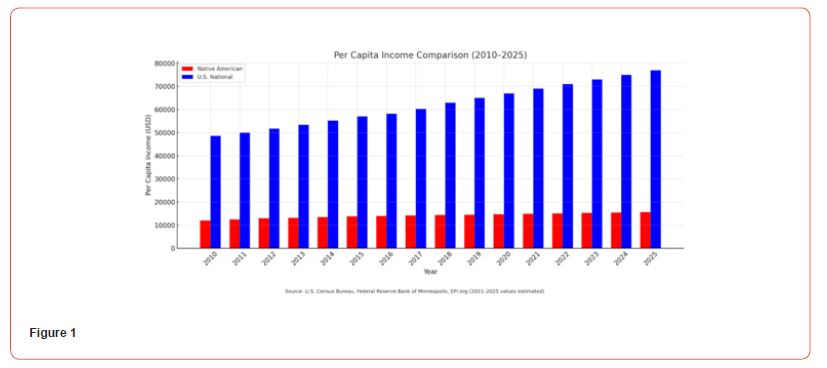

Beginning with GDP per capita, Figure 1 indicates that, for the Native American population, this indicator remained relatively stable at approximately $10,000 between 2010 and 2025. In contrast, GDP per capita for the overall U.S. population increased significantly during the same period, thereby widening the income disparity between Native Americans and the national average.

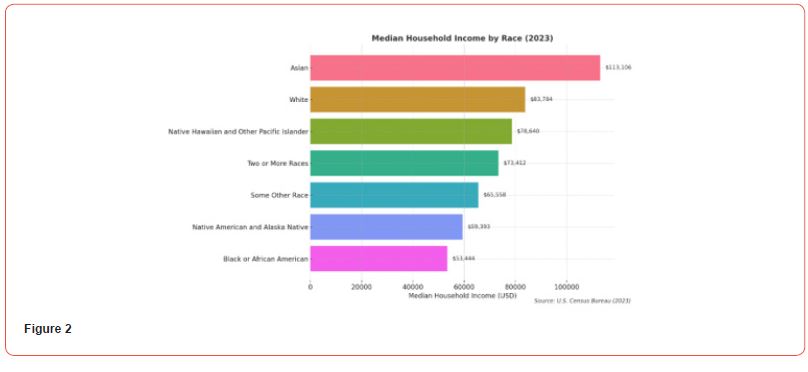

Turning to median household income by race, Figure 2 reveals that, in 2023, Native American and Alaska Native households had the second-lowest median income among the major racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Specifically, their median income was $59,393, surpassing only that of Black or African American households, whose median income was $53,444.

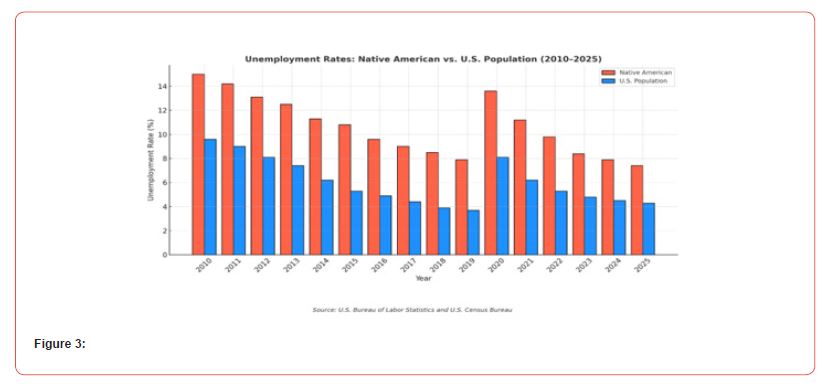

Moving to unemployment trends, Figure 3 depicts a general decline in the unemployment rate among Native Americans over the 2010–2025 period, except for a temporary reversal between 2020 and 2023 attributable to the economic disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, the data indicate that Native American unemployment rates have persistently exceeded those of the overall U.S. population throughout the entire timeframe.

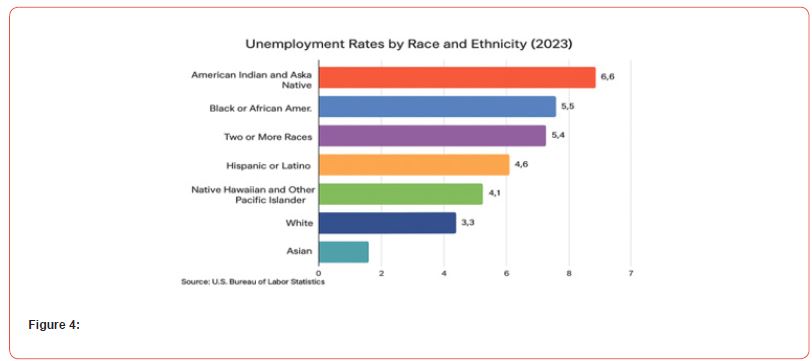

Examining unemployment rates by race and ethnicity, Figure 4 reveals that Native Americans experienced the highest unemployment levels in 2023 - substantially exceeding those of Asians and Whites. Data for 2024 and 2025 are not yet formally reported.

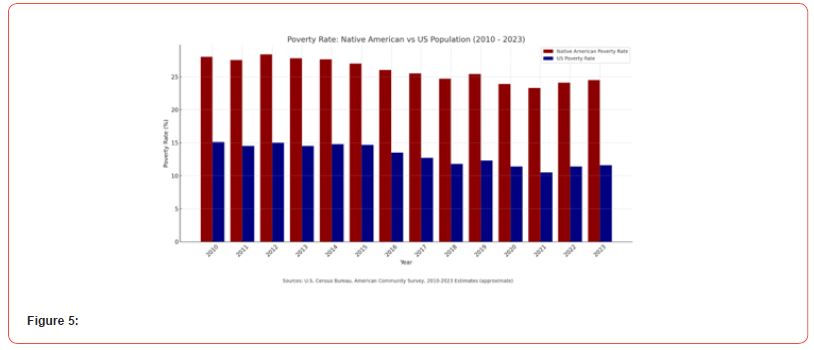

Regarding poverty, Figure 5 illustrates a downward trend in the poverty rate among Native Americans between 2010 and 2023; nevertheless, it has persistently remained above the national average throughout this period.

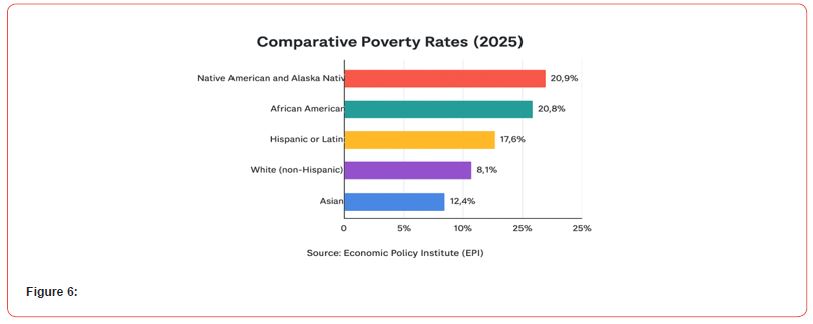

A comparison of poverty rates among major racial groups in 2025 (Figure 6) reveals that Native Americans exhibit the highest poverty rate, followed closely by African Americans. In contrast, there are pronounced disparities when compared to Whites, and especially to Asians, who report substantially lower rates.

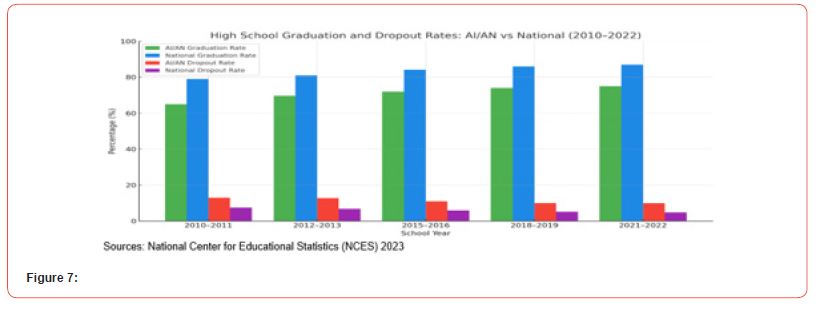

To provide a more comprehensive understanding of the severe challenges faced by the Native American community, it is essential to consider the following additional factors. First, despite modest improvements over the 2010–2022 period, Native Americans continue to exhibit lower high school graduation rates and higher dropout rates compared to the national average (Figure 7).

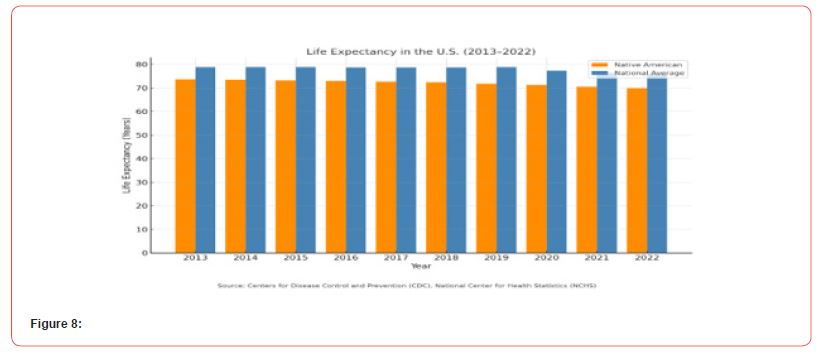

Second, over the past decade, the life expectancy of Nativ Americans has persistently trailed the U.S. average by approximately 4 to 5 years. This disparity was significantly exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, culminating in a life expectancy gap of 9 to 10 years by 2022 (Figure 8).

The preceding aggregate analysis indicates that, despite the improvements in unemployment and poverty rates, Native American communities continue to experience profound and persistent socio-economic disparities when compared to both the national average and other major racial and ethnic groups in the United States. These gains have proven insufficient to redress the deeply embedded structural inequities that remain. Furthermore, while aggregate indicators highlight the broad marginalization of Native populations, they also obscure critical intra-group heterogeneity. As the subsequent section will demonstrate, a disaggregated analysis reveals striking disparities across reservations, with some communities confronting acute socio-economic hardship, while others exhibit notable progress.

What does the disaggregate picture reveal?

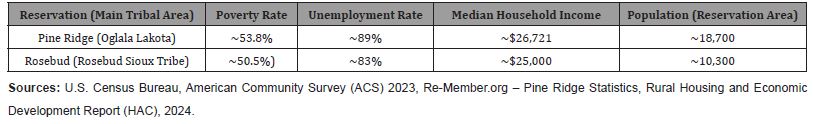

While aggregate indicators consistently show that Native American populations face significant socio-economic disadvantages relative to both the national average and other major racial and ethnic groups, such macro-level analyses tend to mask substantial intra-group disparities. A closer examination reveals that conditions across Native American reservations are far from uniform, with marked differences in socio-economic outcomes. To contextualize the severity of socio-economic disparities, we begin by presenting recent key indicators for two of the most economically disadvantaged Native American reservations in the United States - Pine Ridge and Rosebud - both situated in South Dakota (Table 1).

Table 1: Socioeconomic Indicators for Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations, 2023.

As evidenced by the data presented above, the socio-economic conditions on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations are markedly more severe than the aggregate trends discussed in the preceding section. The Pine Ridge Reservation is characterized by persistently high poverty rates, frequently reported to exceed 50%, with some estimates suggesting levels as high as 80%. Unemployment remains exceptionally elevated, with figures approaching 89%. Median household income is consistently reported to be significantly below national averages, with most sources indicating a value near $26,721, although some estimates suggest it may be as low as $14,000. Similar socio-economic conditions are observed on the Rosebud Reservation. Poverty rates are consistently reported at above 50%, and unemployment is estimated to exceed 80%. Available data suggest that median household income on Rosebud is ap-proximately $25,000, further underscoring the depth of economic disadvantage faced by residents.

In addition to severe economic deprivation, the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations face deeply entrenched social challenges, including elevated rates of substance abuse, mental health disorders, domestic violence, and suicide which contributes to the perpetuation of poverty and social marginalization. As of 2024, the average life expectancy on the Pine Ridge Reservation was approximately 66.8 years, the lowest reported in the United States [1] and the second lowest in the Western Hemisphere, surpassed only by Haiti. In stark contrast to the persistent socio-economic challenges confronting Pine Ridge and Rosebud, the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (SMSC), located in Scott County near Minneapolis, Minnesota, is frequently cited as one of the most economically prosperous Indigenous communities in the United States. Available data indicate that the SMSC maintains a poverty rate of approximately 5 percent and an unemployment rate of around 2.6 percent - both considerably below national averages [2,3]. Although official income statistics for enrolled tribal members are not publicly available, multiple credible sources estimate that the median household income is exceptionally high, bolstered significantly by supplemental income from per capita distributions, tribal enterprises, and social benefit programs. According to William, “each adult, according to court records and confirmed by one tribal member, receives a monthly payment of around $84,000, or $1.08 million a year” [4].

Another notable example of economic advancement among Native American nations is the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma. According to the Cherokee Nation Housing Assessment, the median household income within the Nation’s 14-county service area was approximately $53,800 in 2022, with some counties reaching up to $65,000 [5]. The poverty rate in Cherokee County was 19.3 percent, and the unemployment rate stood at approximately 4.5 percent in 2023 [6]. While historical injustices, including settler colonial violence, forced assimilation policies, and the enduring impacts of federal trust land management, have undeniably shaped the socioeconomic conditions of Native communities, these shared legacies alone do not sufficiently account for the divergent economic outcomes observed among reservations. We argue that a critical explanatory factor in the persistent economic stagnation of Pine Ridge and Rosebud is their profound geographic isolation, which significantly restricts access to markets, business opportunities, and tourism.

Pine Ridge Reservation is situated approximately 120 miles from the nearest urban center, Rapid City [7]. This geographic isolation is exacerbated by inadequate infrastructure, including limited transportation networks, insufficient broadband access - with only about 27% of households reporting reliable internet connectivity [8] - and limited availability of healthcare and utility services. Such remoteness and infrastructural deficiencies constitute significant impediments to economic development, particularly in sectors reliant on accessibility, such as business and tourism. Consequently, these factors substantially constrain employment opportunities and revenue generation within the community.

In contrast, both the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community (SMSC) and the Cherokee Nation have effectively leveraged their geographic proximity to urban centers as a strategic asset in fostering economic development. Located near the Minneapolis– Saint Paul metropolitan area and the city of Tulsa, respectively, these communities are well-positioned to access broader markets, attract tourism, and engage in regional economic networks. Capitalizing on this locational advantage, both nations have made strategic, longterm investments in physical and digital infrastructure, including modernized housing, state-of-the-art healthcare systems, upgraded transportation networks, and high-speed internet access. These investments enhance the business climate and promote tourismbased revenue streams and improve the overall quality of life for tribal citizens.

In the case of the SMSC, economic prosperity has been largely fueled by substantial revenues generated from tribally owned gaming enterprises, most notably Mystic Lake Casino Hotel and Little Six Casino. The profits generated have enabled the tribe to fund robust community development initiatives in areas such as environmental sustainability, education, and public safety. Similarly, the Cherokee Nation has developed a diversified economic base that includes a thriving gaming sector. Through Cherokee Nation Entertainment, the tribe operates more than a dozen casinos across northeastern Oklahoma, including the Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Tulsa. These gaming enterprises play a critical role in fostering economic development on reservations by generating employment opportunities, alleviating poverty, and stimulating local economic growth. In essence, geographic isolation constitutes a fundamental determinant of the economic disparities observed among Native American reservations. For remote communities such as Pine Ridge and Rosebud, sustained and strategic investment in infrastructure is imperative to address structural barriers and to promote longterm, sustainable economic development.

What can be done to improve the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Infrastructure?

As argued in the previous section, infrastructure is vital for socioeconomic development; therefore, it is crucial to critically evaluate the U.S. government’s role in financing these types of initiatives on the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations. Between 2021 and 2024, the U.S. federal government significantly expanded its infrastructure spending in Indian Country, primarily through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA). Under the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Dam Safety Program, funded by the BIL, the Rosebud Sioux Tribe was awarded $26 million for safety improvements to the Antelope Dam [9]. The Oglala Sioux Tribe at Pine Ridge received $58 million to rehabilitate the Oglala Dam [10]. Both communities also qualified for funding under the Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program, which had distributed nearly $980 million in grants nationwide by early 2024, as part of a broader $3 billion initiative to address digital inequity [11].

Although these figures may appear substantial in isolation, they are very modest in comparison to the allocations received by largertribal nations. Most strikingly, the Navajo Nation allocated $521.8 million of its ARPA funding to infrastructure projects - including water systems, broadband, electrification, and housing [12]. This means that the Navajo Nation received more than six times the combined infrastructure investment allocated to both Pine Ridge and Rosebud. This stark disparity cannot be explained solely by differences in population size or geographic scale. Rather, it reflects enduring structural inequities in the federal funding apparatus, which consistently favors a handful of larger tribal nations while relegating smaller or politically marginalized communities to chronic underfunding. These inequities not only perpetuate material deprivation but also undermine the federal government’s legal and moral obligations to ensure equitable development across all tribal nations.

To rectify these disparities and promote a more just and sustainable infrastructure future for Pine Ridge and Rosebud, we suggest the following policies:

a) Establishment of a Tribal Infrastructure Data Center

A dedicated intertribal data center - potentially shared by Pine Ridge and Rosebud - should be created to collect, manage, and analyze real-time data on infrastructure conditions and needs. This center would serve as a critical tool for evidence-based planning, ensuring transparency in federal and state funding decisions. Moreover, it would help document and highlight inequities among reservations, bolstering tribal advocacy efforts and enabling more accurate funding justifications.

b) Creation of a Centralized Tribal Grant-Writing and Technical Assistance Hub

Given the complexity of accessing funds under programs like the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, many tribes face significant administrative barriers. Establishing a permanent, tribally managed grant-writing and technical assistance center would help overcome these obstacles. This hub should train and employ experienced grant writers and provide support for compliance, reporting, and project management, increasing the competitiveness of tribal applications for state and federal infrastructure programs. Studies have shown that administrative capacity is a major barrier to tribal access to federal funds [13], and centralized technical assistance hubs have proven effective in improving grant success rates for tribal governments [14]. Furthermore, the Department of the Interior’s Office of Indian Energy and Economic Development emphasizes capacity-building as essential to maximizing infrastructure investment outcomes in Indian Country [9].

c) Developing Strategic Partnerships with Academic, Nonprofit, and Private Sectors

Strengthening collaboration with universities, nonprofit organizations, philanthropic foundations, and private firms can enhance the technical and financial capacity of tribal governments. These partnerships support infrastructure planning and workforce development while expanding access to non-federal funding streams [13, 15-17, 26].

d) Conducting Political and Public Advocacy Campaigns

Persistent underfunding of tribal infrastructure often stems from a lack of visibility and public awareness. Tribal leaders, allies, and advocates should publish op-eds, policy briefs, and data-driven reports to highlight urgent needs such as unsafe drinking water, impassable roads, and failing energy systems. Coordinated media campaigns, congressional testimonies, and alliances with civil society organizations can increase political pressure for equitable funding allocations [18,19].

e) Institutionalizing Equity Audits in Federal Fund Allocations

Federal agencies such as the Department of the Interior and the Bureau of Indian Affairs should be required to conduct equity audits as part of their funding allocation processes. These audits would assess disparities in per capita infrastructure investments, identify systemic biases, and ensure that tribal nations receive fair and needs-based resources. Regular publication of audit results would enhance transparency and foster accountability [20].

f) Expanding Tribal Sovereignty in Infrastructure Governance

Expanding tribal sovereignty in infrastructure governance involves recognizing and operationalizing the inherent right of tribal nations to self-govern in matters related to the planning, design, implementation, and oversight of infrastructure projects on their lands. Historically, infrastructure development on Native American reservations has often been shaped by federal agencies and nontribal contractors, frequently resulting in projects misaligned with local cultural values and community priorities. By shifting decisionmaking authority to tribal governments, infrastructure initiatives can better reflect the lived realities of tribal citizens. This shift would not only enhance project efficiency and sustainability but also foster a stronger sense of ownership and accountability within tribal communities [18,20-22].

g) Exploring Alternative Financing Mechanisms

g) Exploring Alternative Financing MechanismsWhile federal funding remains essential, tribes should be supported in developing complementary financing strategies. These may include tribal infrastructure bonds, low-interest loan funds, community development financial institutions (CDFIs), and public-private partnerships (PPPs). Tribal infrastructure bonds have been recognized as a viable tool for raising capital by allowing tribes to tap into capital markets while maintaining sovereignty [23]. Similarly, low-interest loan funds and CDFIs provide flexible financing options tailored to the needs of underserved tribal communities [24]. Public-private partnerships have also shown potential in improving infrastructure delivery efficiency and leveraging private sector expertise and investment [25]. Leveraging such mechanisms can reduce dependence on restrictive federal funding cycles and accelerate project timelines.

Some of these initiatives, such as centralized grant-writing hubs, cross-sector partnerships, and alternative financing mechanisms, are already in operation in other parts of IndianCountry, but have not been adapted to the specific needs, scale, and governance structures of Pine Ridge and Rosebud. Others, most notably a dedicated tribal infrastructure data center and the institutionalization of equity audits in federal fund allocations, do not currently exist in a fully developed form and therefore remain aspirational, though they hold considerable potential as instruments for enhancing accountability, administrative efficiency, and long-term strategic planning [26-30]. The systematic adoption and adaptation of this full set of initiatives is essential for closing the development gap in Pine Ridge and Rosebud and fostering a path toward equitable and sustainable development.

Conclusions

This paper deals with the need for a fundamental shift from aggregate to disaggregated analyses to more accurately reflect the entrenched and uneven development patterns across Native American reservations. While aggregate data are useful for identifying broad national trends, they frequently obscure the profound intra-group disparities that persist among tribal communities. At the aggregate level, empirical evidence confirms that Native Americans, as a demographic group, continue to experience the lowest socio-economic outcomes across multiple key development indicators in the United States. Although some incremental improvements have been recorded in areas such as unemployment and poverty, these advances remain insufficient to close the persistent development gap between Native populations and the broader U.S. society [31-34].

Disaggregated data exposes stark disparities in socioeconomic conditions across reservations. While the Pine Ridge and Rosebud Reservations remain mired in persistent poverty, soaring unemployment, and chronically low incomes, other tribal nations - such as the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community and the Cherokee Nation - have attained significant economic prosperity. These disparities cannot be fully explained by the shared historical legacies of colonization, forced displacement, and cultural suppression. Rather, we argue, they are largely driven by geographic isolation and chronic underinvestment in essential infrastructure. The experiences of Pine Ridge and Rosebud underscore the critical role of infrastructure as a foundational driver of development, rather than as a secondary or supportive element. Inadequate infrastructure systematically excludes these communities from economic opportunities, including access to markets, businesses, and tourism, thereby exacerbating unemployment, poverty, and marginalization [35-37].

Despite federal allocations, infrastructure investment in Pine Ridge and Rosebud remains both insufficient and inequitable. To address these long-standing disparities, we suggest a series of integrated policy interventions. These include: the establishment of a joint tribal infrastructure data center to support evidencebased planning; the creation of a dedicated grant-writing and technical assistance hub to improve access to federal resources; and the development of cross-sector partnerships to build local capacity. In addition, robust political advocacy, the implementation of mandatory federal equity audits, and the expansion of tribal authority over infrastructure governance are essential to ensuring that investments are both equitable and culturally appropriate. Exploring alternative financing mechanisms - including tribal infrastructure bonds, low-interest revolving loan funds, Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs), and public-private partnerships - could further supplement federal support and accelerate development outcomes. Some of these initiatives are already in place elsewhere but not tailored to Pine Ridge and Rosebud, while others remain aspirational; together, they are essential for closing the development gap and advancing more equitable and sustainable development.

- Re-Member (2024) Pine Ridge facts.

- S. Census Bureau & U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.).

- Indian Country Today (2022) Poverty and economic challenges on reservations. Indian Country Today.

- William T (2012) $1 million each year for all, as long as tribe’s luck holds. The New York Times.

- Housing Authority of the Cherokee Nation (2024) Cherokee Nation Housing Assessment: Development Strategies.

- American Community Survey (ACS) (2023) American Community Survey U.S. Census Bureau.

- Bureau of Indian Affairs (2023) Infrastructure programs and funding. U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Federal Communications Commission (2021) Schools and Libraries Universal Support (E-Rate) – Tribal Broadband Access.

- S. Department of the Interior (2023) Bureau of Indian Affairs announces $26 million investment in Rosebud Sioux Tribe’s Antelope Dam.

- KOTA Territory News (2024) Biden administration investing $58 million in Oglala Dam restoration.

- National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) (2024) Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program. U.S. Department of Commerce.

- Office of the President and Vice President, Navajo Nation (2024) Navajo President Buu Nygren signs ‘monumental’ ARPA legislation to leverage funds, double infrastructure projects to be built Office of the President.

- National Congress of American Indians (2021a) Administrative capacity in tribal governments: Barriers to federal funding access.

- S. Government Accountability Office (2022a) Indian programs: Additional data and analyses needed to improve funding equity (GAO-22-104567).

- National Congress of American Indians (2021b) Tribal infrastructure and economic development: Opportunities through partnerships.

- S. Government Accountability Office (2020) Tribal infrastructure: Collaboration with non-federal partners can help address challenges (GAO-20-451).

- The Rockefeller Foundation (2019) Advancing equity through cross-sector partnerships: A guide for tribal communities.

- Native American Rights Fund (2021) Advocating for tribal infrastructure funding: Strategies and successes.

- Congressional Research Service (2020) Federal funding and infrastructure challenges in Indian Country (CRS Report No. IF11612).

- S. Department of the Interior (2020) Indian Affairs: Infrastructure and Tribal Self-Governance.

- National Congress of American Indians (2019) Tribal sovereignty and self-governance: Foundations for infrastructure development.

- Indian Law Resource Center (2021) Supporting tribal self-governance in infrastructure projects.

- Royster A (2018) Tribal infrastructure bonds: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Tribal Finance 5(2): 45-59.

- National Congress of American Indians (2020b) Policy brief: Ensuring equitable funding for tribal infrastructure.

- S. Government Accountability Office (2019) Public-private partnerships: Key considerations for infrastructure projects on tribal lands (GAO-19-345).

- Rural Housing and Economic Development Report (HAC) (2024) Pine Ridge Statistics. Washington, DC: Housing Assistance Council.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2023) Mortality in the United States, 2023 (National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 521).

- Department of the Interior (DOI) (2023) Office of Indian Energy and Economic Development annual report. U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Economic Policy Institute (EPI) (2025) Comparative poverty rates.

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (2024) Center for Indian Country Development.

- National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) (2023) High school graduation rates. In Condition of Education 2023.

- National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (2023) United States life tables.

- National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) (2019) Tribal Infrastructure Development: A Pathway to Tribal Self-Determination.

- National Congress of American Indians (2020a) Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) and tribal communities.

- S. Department of the Interior (2021) Equity and inclusion strategic plan.

- S. Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Energy and Economic Development (2023) Tribal Energy Development Capacity Grant Program.

- S. Government Accountability Office (2022b) Tribal infrastructure: Federal assistance and challenges in accessing funding (GAO-22-105).

-

Giuliana Campanelli Andreopoulos*, and Alexandros Panayides. Beyond the Aggregate: Uneven Development and Target Policies for Native American Reservations. Iris J of Eco & Buss Manag. 3(2): 2025. IJEBM.MS.ID.000557.

-

Native americans; uneven development; target policies; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.