Research Article

Research Article

The Persistence of Gender Disparities in Occupational and Promotional Achievement

Susanna Tardi2, Alexandros Panayides1 and Giuliana Campanelli Andreopoulos1*

1Professor of the Economics, Finance and Global Business, William Paterson University, USA

2Professor of the Sociology, William Paterson University, USA

Giuliana Campanelli Andreopoulos, Economics, Finance, and Global Business, William Paterson University, USA.

Received Date:February 13, 2024; Published Date:March 04, 2024

Abstract

Women have made significant advances in education at every level. However, gender disparities persist in occupation and promotional advancement. The scope of this paper is to provide empirical evidence and explanation for these overall disparities with attention to Finance. In doing so, we apply and emphasize a sociological approach. We also recommend more comprehensive private and public practices and policies to promote positive and equitable work environments.

Introduction

Women have advanced at all levels of education however, gendered occupational disparity and lower levels of career advancement persist in all countries and societies. These disparities are evident in the STEM areas, particularly in engineering and computer science, but also in business-related fields such as Finance. This paper focuses on three objectives: (1) examining the empirical data on occupation by gender; (2) presenting and evaluating the factors that impact occupational gender disparities in general and Finance in particular, and (3) reviewing existing policies that impact gender occupational disparities and suggesting more comprehensive recommendations to reduce these disparities and promote increased opportunities for women to break the glass ceiling.

We acknowledge the importance of the intersectionality of race, gender, and social class in understanding occupational choice and advancement, but in this paper have decided to focus on gender. The researchers of this paper are university professors with an interest in the factors that influence women in “choosing” majors and careers, and particularly those focused on Finance. There are two main reasons for choosing Finance: (1) It is generally perceived as a male occupation and (2) Substantial empirical evidence is available in this area while lacking in others. By examining general research on gender and occupational “choice” and integrating personal academic expertise and experience, this study develops a framework for future research on gender and decision-making regarding majoring in and having a career in Finance.

Women in Education and Careers: Empirical Evidence

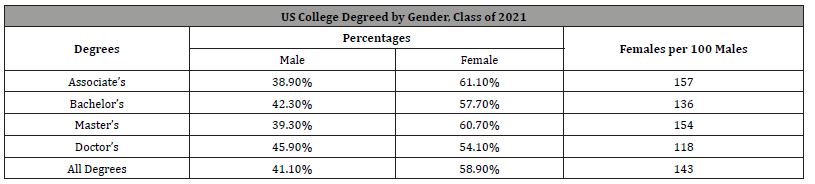

According to the Department of Education (See Table 1), females are exceeding males at every degree level from Associate to Doctorate degrees (2021) with the greatest divergence of 22.2% at the Associate level and 21.4% at the Master level.

Table 1:

Source: US Department of Education.

Turning to the major in which women achieve a bachelor’s degree, evidence shows (See Figure 1) that from 1971 to 2019, the four most popular majors for women are Health Professions, Public Administration, Education, and Psychology. In the same timeframe, the least popular majors for women are Engineering and Computer Science.

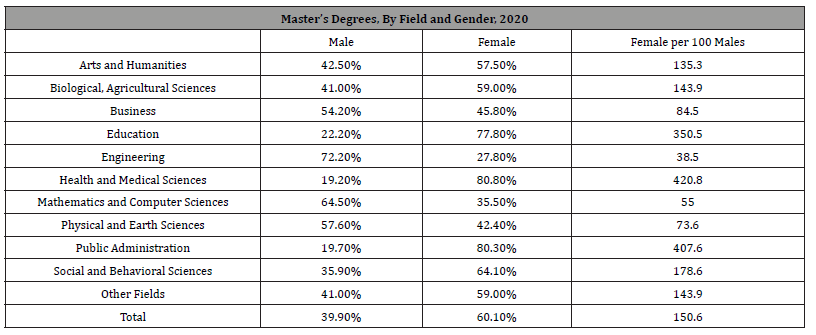

According to 2020 data from the Council of Graduate Schools (See Table 2), males and females differ approximately 9% in master’s degrees earned in Business (males 54.2%; females 45.8%). However, master’s degree attainment in the Health and Medical Sciences and Public administration is significantly higher for women (80.8% and 80.3% respectively) than for men (19.2% and 19.7% respectively).

Table 2:

Source: Council of Graduate Schools.

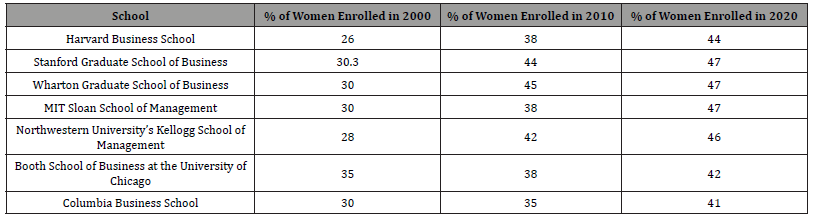

Additional evidence from 2000 to 2020 shows that there has been a significant increase in the percentage of women enrolled in the top business schools ranging from 7% in the case of Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago to 18% at Harvard Business School (See Table 3). The growth of women majoring in Finance at the top business schools is probably due to the fact that Finance is one of the most fast-growing and dynamic sectors of the US economy mainly due to technological advancement and financial innovation.

Table 3:

Source: Quantic 2022.

As Figure 2 shows, there has been a substantial increase in jobs in financial activities over the 2015-2023 period, with the only exception of 2020 since the coronavirus was associated with a substantial job reduction.

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projects that business

and Finance jobs will continue to increase over the 2022 to 2032

period, with an average of 911,400 openings each year. It is

important to note that Finance professionals earn above-average

salaries: in 2022 personal financial advisors earned a median

annual income of nearly $95,390 which is more than double the

median annual salary for all occupations nationwide. Financial

analysts-one of the most common careers in Finance-earned a

median annual salary of $96,220 in the same year [1]. However, the

sustained employment growth of the financial sector, as illustrated

in Figure 2, hides important differences related to gender. Here

are five crucial facts that can illustrate what really happens in the

financial sector.

1) At the entry level there is no significant difference between

men and women since women account for 46 percent of

employees.

2) The distribution of women within the Finance sector highly

differs. As Figure 3 shows, women are almost nonexistent on

the trading floor while their presence in insurance is much

higher than that of men.

3) Women in Finance are more prone than men to leave their

jobs. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, over the

2000 to 2010 period, 141,000 women, 2.6% of female workers

in Finance, disappeared from the industry, while men in the

industry grew by 389,000, or 9.6%. A survey by the Pew Center

for Research showed that men outnumber women by almost

three to one at the middle-management level [2].

4) Women are greatly underrepresented at the C-suite level,

the chief executive level. According to the Deloitte Center for

Financial Services, only six of the 107 US largest financial

institutions were run by female CEOs in 2019. In venture

capital firms (VC) only 4.9 percent of the partners are female,

and in private equity (PE) fewer than 10 percent of the senior

roles are held by women [3].

5) According to a 2021 Mc Kinsey Report based on 71 financial

service employers, despite the progress made by women over

the 2018- 2021timeframe, 64 % of the C-suite executives are

still white men. Thus, the highest level of the corporate ladder

is still dominated by white men (See Figure 4).

Understanding Gender Disparities in the Workplace

Researchers have examined numerous factors to explain occupation-related gender disparities focusing on one or some combination of the following factors: biological, psychological, and sociological (socialization).

Biological determinism suggests that men and women have limited control over their behaviors. Proponents of this theoretical approach claim that by nature women are nurturers and men are naturally aggressive and competitive. Biological theories do not distinguish between sex and gender. They attribute hormones and chromosomes as the determinants of gender. According to this perspective, women and men choose occupations that align with their natural, biological makeup.

Stern and Madison acknowledge environmental influence regarding occupational segregation but highlight the importance of biologically based sex differences that result in “occupational choice.” They suggest that humans follow their preferences, interests, and goals while simultaneously being sensitive to social norms. Their stated intent is to convince economists to take sex differences in psychological traits seriously. According to this perspective, the overwhelming concentration of women in health, public administration, education, and psychology fields is the result of their personal decisions and there is no need for policy intervention.

While biological perspectives concentrate on “nature,” psychological perspectives combine “nature” and “nurture.” Dawson approaches the explanation for gender disparities in occupational choice from a psychological perspective utilizing the concept of risk aversion. He reports that women have a lower willingness to take risks, have higher levels of loss aversion, and lower levels of financial optimism than men [4]. The stereotype of women being more risk averse than men remains prevalent in many societies. However, there is evidence that women are not more risk averse than men, but researchers have focused on stereotypically defined masculine risk behaviors [5]. Some researchers fail to consider the context of the risk: the anticipated loss or gain from taking the risk and previous experience with risk taking. At work, women tended to experience greater loss, more negative consequences than men, and this negatively influences future risk-taking. Survey findings suggest that women in managerial positions take risks and may embrace risk, but their risks remain invisible because American culture does not expect them to take risks [6]. We support Morgenroth et al. conclusions regarding gendered risk taking and apply their interpretation to the case of women in Finance later in this paper.

Biological perspectives focus on hormonal and chromosomal gender differences, psychological perspectives concentrate on personality traits, and the socialization perspectives emphasize the role social institutions play in mindset development and occupational choice. We acknowledge that biology, personality, and life-long socialization all affect decision making. However, we believe that how the individual learns societal norms and values (socialization) has the most important influence on decision making, including occupational disparities that result in occupational segregation.

Socialization technically begins with the sex identity of the fetus and continues until the end of the life cycle. Prior to the birth of a child, parents select the colors and types of sex appropriate clothing, toys, furniture, and bedding they will purchase. Notions of masculinity and femininity precede the birth of the child. Pink is the color for girls and blue for boys. Later in life the traditional jobs that females attain will be referred to as “pink labor.” If the infant female child has very little hair, they are careful to purchase pretty pink and rather large hair bows to avoid anyone identifying their daughter for a son. Once the child is born even the tone of voice used and manner of handling the child varies according to the sex of the infant. Socialization occurs in all countries but is culturally specific. Research has consistently identified the significant role that parents play in a child’s life. Parents serve as role models particularly in terms of parental work and family experiences [7] and in determining what the child will and will not be exposed to [8]. Parents initially instill notions about work ethics, values, and money, but as the child encounters social institutions, familial norms and values are generally reinforced but occasionally challenged. The educational institution has been found to have an impact on occupation as early as grammar school. The schools’ children attend are determined by parents depending on norms, values and income. A study of fourth and fifth grade children found that occupational knowledge, gender stereotypes and pressure to conform to gender norms influence children’s career interests [9].

The initial and main interaction between a child and society are family and school and are associated with gender roles and occupational choice capacity [10]. Kocak et al. conducted a study in Turkey where gender roles are even more prominent than in the West. They found that the career process is influenced and shaped by the quality of experiences learned in childhood and affects their career choices. According to Kocak et.al, children who are raised in supportive households where opportunities are not dependent on gender, and who have an interest in school have greater likelihood of setting and striving to achieve future goals. The future of individuals and societies necessitates raising children to be free and competent in their career choice, absent of imposed gender roles, and aligned with the needs of the society in which the individual lives (Ibid). The challenge is balancing free occupational choice with societal needs. The US is a primary example of choice not in alignment with societal needs. In the cases of STEM, Finance, and even in education, we are confronting serious labor shortages occurring in both private and public sectors.

Historically, women’s involvement in the labor force in the US has been manipulated by societal norms promoted largely in the institutions of family, school, and media. The individuals who have the most influence in a child’s life are parents. They are the first individuals who help mold the child’s ideas about work ethics, general values and those specifically related to money. Social and cultural norms are initially taught in the family but reinforced throughout the development of an individual in all social institutions. Traditional gendered socialization defines a man’s role by occupational and financial advancement and a woman’s role as a homemaker. During WWII, women were needed in the labor market to perform the duties that men serving in the armed forces previously performed. Financial necessity and the media emphasized and promoted the need for women to step up and do their part for the war effort. Rosie the Riveter became the media model to depict a positive image of a woman in a traditionally male role. While many women enjoyed their participation in the labor force, their needs/wants were no longer societal priorities when the War ended. After the war, the media message shifted to emphasize that women were in the job market only to protect the jobs for their male relatives returning from war. The emphasis was on the proper role of women in the home rather than in the labor force. Educational and political improvements contributed to normative acceptance of women working outside of the home, while economic need forced them into the labor market. Unfortunately, women continued to be expected to serve the needs of the home and family. By working outside of the home, women were provided an opportunity to have careers and some financial independence, but the pressure of work and home labor increased stress, reduced life satisfaction and career expectations. Women currently engage in more household labor than men [11]. Work/family conflict has been identified as contributing to the loss of women in the labor market [12,13,18]. In the case of Finance, as stated in previous section of this paper, some women abandon their careers.

Townsend et al. [12] identified a pathway from gender role mindset to family-work conflict, to reduced job and relationship satisfaction. Gender role mindset is the result of what individuals are socialized to believe their appropriate societal role is based on their gender. This pathway may be useful for understanding why women drop out of full-time work. Townsend et al. concluded that women with fixed, traditional gender role mindsets were more likely to resist the notion that they can “have it all.” Underaged, fixed mindset undergraduate women business students but not men were found to anticipate having to choose between a successful career and family [12]. They also suggested that since undergraduate women were unlikely to have experienced the work-home life conflict, they may actually underestimate the issue. More flexible, growth anticipated mindsets may help reduce occupational gender disparities. There are three elements that research identified as preventing undergraduate women from entering careers in business: (1) fewer opportunities to receive appropriate mentoring, (2) substantially less information than males, and (3) greater emphasis being placed on work/life balance which negatively impacts their preferred career choice [14].

For the nation the labor participation rate for women was 56.8% in 2022. The age groups of 25 to 34 years, 35 to 44 years, and 45 to 54 years all had participation rates above 75.0%, with 25 to 34 years having the highest(77.6%) [15]. The labor participation of women in other countries is significantly lower. Whether or not women are in the labor force, the socialization of women worldwide prioritizes patriarchal norms and values. Gendered differences persist across all industries and most occupations, at all ranks including low-level workers, mid-level managers and in senior positions [16]. Based on societal norms and values, women and men are geared toward different industries and jobs. Female jobs are more altruistic and social (i.e. teaching, public health and administration, and nursing) whereas male jobs are of higher positions (status) with higher pay (i.e. teaching, public health and administration, and nursing).

In the case of leadership, there is only one stereotypical profile—the individual needs to step up and “lean in.” While leadership requires individuals to step up and “lean in,” research suggests that encouraging women to “lean in” and take greater risk is likely not to decrease gender inequality [4]. Experience has shown that when women step up to the table and “lean in,” it is frequently portrayed in predominantly male environments as inappropriate, aggressive behavior or is ignored until a man voices the same opinion. In such cases, women learn that the outcome of “leaning in” simply results in greater frustration for not having their ideas and opinions validated until they are presented by a man. When a man “leans in” and speaks out, he is considered to be assertive and is acknowledged by peers, thereby reinforcing the male behavior. The differential treatment of men and women regarding speaking contributes to discrepancies in careers, pay gaps, and occupational segregation.

Research suggests that workers’ perspectives on women’s role in society influences the larger gender gap in worker burnout, meaning that women raised with traditional norms are more likely to report burnout [17]. In traditional male occupations like engineering, the following areas have been identified to attempt to account for why women leave the profession: poor and/or inadequate compensation, poor working conditions and work environments that made work- family balance difficult, ineffective use of their math and science skills, and lack of recognition and advancement [18]. These reasons also help to account for women in Finance leaving the field which we will discuss in the next section of the paper.

In the above theoretical section, we emphasize the importance of socialization for explaining gender disparities in occupational attainment and career growth. Traditional mindsets, gendered work and home labor expectations, differential risk taking and mentoring behavior and experience are all important elements for understanding the occupational challenges that women encounter in the labor market. These are also important factors in understanding the occupational experiences of women in Finance.

The Case of Finance

Qualitative data on college students electing Finance as their major is lacking, and as previously discussed, quantitative data is limited. However, there is substantial research [19,21,28] and media articles [3,22] on the relationship between gender and Finance examining the attitudes and advancement trajectories of women already in this career. The literature emphasizes many of the issues previously discussed to explain the challenges that women encounter in most of the professions in which they are involved.

To explain the condition of women in Finance, and particularly

their difficulty in reaching the C-level, we need to recall the three

main obstacles that they encounter in the workplace:

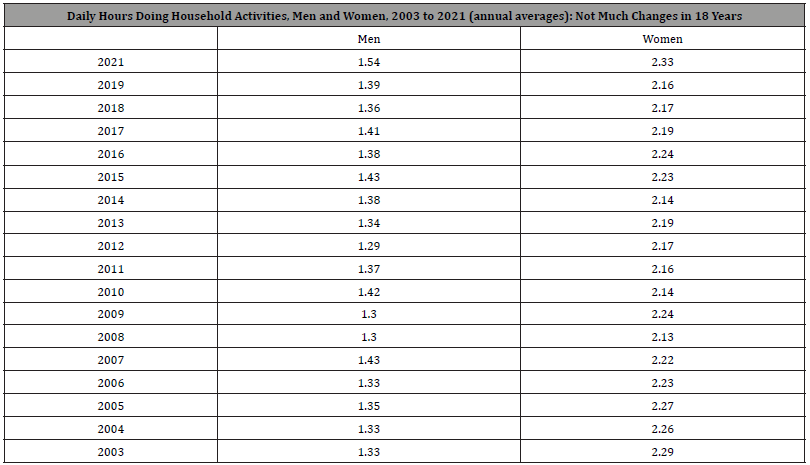

Difficulty of Balancing Work and Family Life: Women

entering the financial field can be very competitive and have high

expectations concerning their careers. However, in mid-career,

many of them decide to concentrate on their private lives, and at

this point, they may “exit.” Empirical research shows that women

spend more time than men on family responsibilities as caring for

children and elderly family members. As Table 4 below shows, in

the US women work between 30 and 45 minutes more than men on

daily household activities. This disparity persisted over the whole

2003-2021 period. In the case of families with children under age

13 women spend at least twice the amount of time that men do

juggling both childcare and household activities.

In addition, in the workplace, women are more likely to provide emotional support to co-workers and organize social events. The result is that they have a higher rate of burnout at their job than men with some deciding to quit [22,23].

Table 4:

Source:American Time Use Survey, BLS and U.S. Census, Historical Data.

Lack of Mentorship and Networking: Many women in Finance cite a lack of role models and/or mentors as a major deterrent to help develop the necessary skills, knowledge, and connections, crucial for climbing the corporate ladder. Working with female financial mentors has the benefit that they understand women better because their experiences are similar and know how to overcome the types of obstacles women typically face. According to the Harvard Business Review [20], mentoring is the most significant activity for increasing diversity and inclusion at work compared to diversity training and other diversity initiatives. Since the majority of those in Suite-C or any high-level corporate position tend to be male, women who choose occupations in less flexible, highly competitive fields, find themselves embedded in “old-boy” networks. In this scenario, women often find themselves without mentor. They sometimes have to search for what the Harvard Business Review refers to as “male champions,” men in leadership who are willing to mentor women within the organization. Only having female mentors does not resolve the problems women in Finance encounter. A wider mentoring network is required.

Low Expectations

While women enter the field of Finance with optimism regarding their careers, their increasing difficulties balancing work and family life as well as the lack of mentoring and networking results in low expectations for their future. This is mainly due to the climate that they see in the workplace where prejudice, stereotypes, and discrimination against women continue to thrive [19,21]. In some cases, women’s expectations are so low that they are reluctant even to enter a particular field. This is the case of the trading floor since it is perceived as an “alpha male territory” populated by highly confident, very bright, extremely competitive, and unemotional men [24]. From an economic perspective, one can say that women in Finance are facing high costs and low returns in terms of career opportunities and consequently, income. Challenges of balancing work and home, inadequate mentoring and networking, and low expectations are common patterns that women who work in stereotypical “female” fields experience [21]. However, Finance appears to represent an extreme case of the gendered biases confronted by women who work in non-traditional fields.

Policy Recommendations

The presence of women in occupations in which there is significant gender disparity, including Finance, should be encouraged for the following reasons: (1) empower women and promote a more equitable environment, (2) produce better decision-making, (3) increase innovation and creativity, and (4) meet the necessary needs of a changing labor market. Social problems are produced by gendered occupational attainment [16]. These problems include labor shortages and organizational productivity. In certain fields, the shortage of workers forces labor needs to be dependent on those from other countries. Some of the current unmet US labor needs are not due to individuals lacking talent and skills, but more likely the product of having been socialized to develop a mindset that defines what jobs are appropriate given their gender. Reducing gendered occupational disparities may also reduce labor shortages and produce a positive effect on profitability. A positive work environment is likely to increase worker productivity, attract a larger talent pool, and improve retention. It is not productive for a company to lose trained employees and costly to search for new ones. Thus, it is very important to suggest policies able to alleviate the obstacles that women usually encounter in the workplace.

Existing Practices and Policies

To help women balance work and family life we will summarize existing practices and policies and recommend additional ones.

Flexible Schedules for Women: It is not very difficult to implement greater flexibility, since as the COVID experience has shown, the transition to remote work is quite common in many industries including Finance (except for the trading floor). Technological advances and changes in workforce expectations that arose during the pandemic persisted subsequently and resulted in women’s increase in seeking greater job flexibility.

Family Leave for Men and Women: Paternity as well as maternity leave not only increases gender equity in the workplace, but also promotes child bonding and improves children’s development. The ability for workers to take leave with pay to care for a newborn, recover from a serious illness, or care for an ill family member reduces stress and increases job satisfaction [21].

Childcare Subsidies: Childcare is both time-consuming and expensive. Some organizations provide childcare subsidies to help women, especially those at low-ranking levels with relatively low incomes, in maintaining their current jobs and positions.

Reentry Programs: Reintegrating employees who have previously left the workforce, particularly those employees who have taken time off to raise children, is beneficial for both employees and employers. We acknowledge that several financial companies have already implemented some of the above-mentioned programs. For example, JP Morgan Chase has implemented a Reentry Program to help employees return to work after they have been absent from the workforce for over two years. This particularly applies to women who have newly born children and/or have traditional responsibilities for caring for sick and elderly parents.

Mentoring and Networking: As previously discussed, the degree of mentoring and networking women receive in the workplace is limited. Some corporations like Ernst & Young LLP, Goldman Sachs, and JP Morgan have introduced programs in which senior leaders helped women (and minorities) to rise in the organization. JP Morgan Chase has been very active on this front by promoting a program entitled “Women on the Move” which is an organization dedicated to advancing females’ careers and Finances. Nonprofit organizations such as “Girls Who Invest” offer programs to bring young females into the world of Finance through internship and mentoring programs [3]. Finally, Women in Financial Service (WIFS) is one of the largest women’s associations empowering women in the insurance and financial services profession.

Some corporations have also implemented sponsorship programs as an extension of mentoring. These programs involve designating a person with a significant influence on decision-making processes who can actively promote women’s career advancement. This strategy seems to have a multiplier effect meaning that one woman in the C-suite is correlated with three women in senior management roles [25].

Looking Toward the Future: Additional Practice and Policy Recommendations

In light of the analysis of existing quantitative and qualitative data regarding gender disparities in occupation, we believe that existing policy recommendations need to be modified, enhanced, or added. The recommendations we are making are relevant for all non-traditional, female occupations and particularly for Finance. The following are our suggestions.

Educating the Educators: While modifying societal norms is a slow, difficult process, it can be aided by social policy interventions. Changing the mindset of women to increase expectations is a key element to reduce gender occupational disparities. Federal and State Funded Grants need to be made available to retrain grammar school, high school, and college educators on how to provide positive career expectation advisement to both males and females to challenge the existing gender role approach. To eliminate the existing gender-based mindsets, male and female children need to be socialized to be empowered to believe that there are not barriers to their career choice. An optimistic mindset is a prerequisite to making women believe that they can enter and succeed in any career. Competitive and risk-taking behavior needs to be taught, encouraged, and rewarded to women and men equally.

Equalized Job Flexibility: During the pandemic, both men and women experienced job flexibility through shorter work weeks, hybrid, and remote work. Much of the literature emphasized the need for job flexibility for women. In reality, post-pandemic, both men and women expressed a desire to maintain work schedule flexibility. Men reported enjoyment in the family bonding time that flexible schedules provided. Balancing work and private life is not only the job and desire of women, but is a necessity for both men and women. We recommend that the public and private sectors recognize the importance of enhanced work flexibility for both genders, since this will result in greater workforce satisfaction with a positive effect on productivity and worker retention.

Inclusive Mentoring: Existing mentoring programs are generally based on the principle of women mentoring other women. We concur with the Harvard Business Review regarding “champion males” as an integral part of occupational mentoring. We specifically suggest that organizations need to emphasize the importance of men and women being equally involved in mentoring. Financial and career advancement Incentives such as being considered as a criterion for promotions, should be provided in order to further encourage this participation.

Inclusive Promotional Advancement: Criteria for career advancement are highly subjective. Male-dominated careers function according to “old boy” networks in which men tend to promote men. Women in male-dominated fields such as Finance have cited this as an obstacle to their job satisfaction and advancement. We suggest developing promotional criteria that recognize the work that women are generally engaged in without recognition (i.e. co-worker mentoring and event planning). In addition, more women need to be included in the promotional decision-making process. Women tend to have a better understanding of, and experience with, the challenges that other women encounter in their respective fields.

Increased Financial Remuneration for People-Oriented Careers: While we did not focus on income in this paper, we choose to include a policy recommendation involving this aspect, since it is well-documented that women are paid less for equal jobs with an equal level of education. In addition, many people-oriented careers (i.e. teachers, health aides etc.) dominated by women are typically paid less than thing-oriented careers (i.e. engineering, computer science) dominated by men. People-oriented jobs are crucial for the well-being of any society and need to be respected and valued. This should be translated into higher pay for people-oriented jobs. Closing pay gaps between these two types of job orientations will reduce job segregation. Having more men in people-oriented jobs will also reduce the differential power that is often created in the family, since currently women are in lower paying jobs than men.

Tax Reduction for Organization and Government Intervention: If significant progress is to be made in reducing gender work disparities, government as a social institution will need to do more to support gender work equality. Government leaders cannot merely “talk the talk” regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), but need to do more to “walk the walk.” They can achieve this goal by tax reductions (tax relief) for organizations that can provide evidence of implementing programs aimed at reducing gender disparities (i.e. diversified mentoring, increased networking opportunities for women, increase in the number of promotions for women). The challenge of implementing policies to reduce pay gaps involves two protagonists: the government and the private sector. The private sector cannot be mandated to increase women’s salaries, although there are existing laws to protect against gender discrimination. On the other hand, additional federal and/or state legislation needs to be proposed, passed, and implemented to reduce gendered wage gaps. Currently there are an insufficient number of women in both education and nursing to meet societal needs, particularly in countries with an aging population. An increase in salaries in these professions will encourage more individuals including men, into these fields. Government intervention seems to be necessary for societal occupational needs to be met.

Conclusions

This paper examines the persistence of gender disparities in occupational and promotional achievement with particular attention to women’s experiences in Finance. We provide trend data highlighting the educational and occupational achievements of women as compared to men and an elaboration of career opportunities in the case of women in Finance. Although women exceed men in educational attainment at every level, women remain concentrated in female-dominant (people-oriented) occupations— health, public administration, education, and psychology; men are concentrated in thing-oriented activities—engineering and computer science. The case of Finance shows that even though in the entry levels there is not significant divergence between men and women, recognition, support, and promotional opportunities are extremely limited for women at the highest, C-Suite level.

Particular attention is given to the importance that socialization plays in occupational decision making. While both nature and nurture play a role in this process, we believe that nurture has a stronger mediating influence. All of the societal agents of socialization play a part in influencing gendered roles. While there is biological and psychological evidence of women’s tendency to be nurturing, the systemic gender divisions promoted by the social institutions further support and enhance this tendency. The result is that societal expectations becomes reality and so women “choose” female oriented occupations.

Societal norms specify differential expectations for men and women regarding work and family. Women are expected to engage in work and simultaneously find ways to balance work and family life, while men are expected to engage in work and providing for the financial security of the family. This results in women perceiving work as conflictual with family life and lowering the expectations for career choice and growth. In addition, women do not receive the same mentoring and network opportunities as men, especially in male-dominated occupations for two main reasons: (1) in a maledominated environment, men promote men and (2) women are expected to provide co-worker support as well as being in charge of activities for which there is no recognition (i.e. planning social events, and co-worker support). Given the life-long and relatively consistent traditional gendered messaging and experience, it is misleading to conclude that women “choose” their occupation and career path within the organization/s in which they work.

Societies have experienced changes over time, yet the gendered messaging regarding men’s and women’s expectations have not significantly changed. This study attempts to emphasize that beginning with early familial socialization, girls and boys need to see familial role models who have more significantly shared mutual expectations of work and home labor. To reduce gendered occupational disparities, girls need to be raised in environments (home, educational, peer, and work) that encourage limitless possibilities regarding occupation and the notion of being able to “have it all.” The way they can have it all is by having greater societal expectations for men in their respect for women, increased home labor participation, and significantly improved willingness to mentor and promote women as well as men.

Turning to policy recommendations, we provide an overview of existing policy and practice recommendations as well as additional suggestions to reduce gender disparities in occupation. The existing recommendations include the following: flexible work schedules for women, family leave for men and women, childcare subsidies, re-entry programs, and women-to-women mentoring and networking programs. We suggest the following more inclusive and comprehensive practices and policies: educating the educators, equalizing job flexibility, inclusive mentorship, inclusive promotional advancement, greater financial remuneration for people-oriented jobs, and tax reductions for organizations able to reduce gender disparities. We believe that changing societal needs require greater participation of men at home, and increased respect and support of women at work. We also recommend public and private sector intervention to alleviate the gender disparities in career choice and career advancement. Finally, we suggest federal and/or state intervention through the proposing, passing, and implementing of legislation to reduce occupational gender disparities.

In light of our investigation on occupational gender disparities, we suggest future research on the following: student choice by college, gender and major; career growth opportunities by profession and gender; and longitudinal as well as cross-sectional quantitative and qualitative data on occupational changes by gender.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Whittle Matt (2024) Why pursue a career in Finance and what to consider before you start. Forbes Advisor.

- Taylor Guinevere (2018): Why do women leave the financial services? “https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-do-women-leave-financial-services-guinevere-taylor/

- Chandler Sarah (2022) Why are so few women in Finance? It is complicated. Investopedia February 25: 1-5.

- Dawson Chris (2023) Gender differences in optimism, loss aversion and attitudes towards risk. British Journal of Psychology 114(4): 928-944.

- Morgenroth Thekla, Michelle K Ryan, Cordella Fine (2022) The Gendered Consequences of Risk Taking at Word: Are Women Averse to Risk or to Poor Consequences. Psychology of Women Quarterly 46(3): 257-277.

- Maxfield, Sylvia, Mary Shapiro, Vipin Gupta, Susan Hass (2010) Gender and Risk: Women, Risk Taking and Risk Aversion. Gender in Management 25 (7): 586-604.

- Lawson Kate M, Ann C Crouter, Susan M MCHale (2015) Links Between Family Gender Socialization Experiences in Childhood and Gendered Organizational Attainment in Young Adulthood. Journal of Vocational Behavior 90: 26-35.

- Bornstein MH, Mortimer J, Lutfey K, Bradley R (2011) Theories and processes in life-span socialization. In: Fingerman KL, Berg CA, Smith J, Antonucci TC (Eds.), Handbook of life-span development pp.27-55.

- Barth Joan M, Stephanie L Masters, Jeffrey G Parker (2022) Gender Stereotypes and Belonging Across High School Girls’ Social Groups: Beyond the STEM Classroom. Social Psychology of Education 25 (1):275-292.

- Kocak Orhan, Meryem Ergin, Mustafa Z Younis (2022) The Associations Between Childhood Experiences and Occupational Choice Capability, and the Mediation of Societal Gender Roles. Healthcare 10(6): 1004.

- Bianchi, Suzanne M, Melissa A Milkie, Liana C Sayer, John P Robinson (2000) Is Anyone Doing the Housework? Trends in the Gender Division of Household Labor. Social Forces 79(1):191-228.

- Townsend Charlotte H, Laura J Kray, Alexandra G Russell (2023) Holding the Belief That Gender Roles Can Change Reduces Women’s Work-Family Conflict. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin.

- Van der Lippe T, Lippenyi Z (2020) Beyond Formal Access: Organizational Context, Working from home, and Work-Family Conflict of Men and Women in European Workplaces. Social Indicators Research 151(2): 383-402.

- Gallen Yana, Melanie Wasserman (2021) Informed Choices: Gender Gaps in Career Advice. IZA Discussion pp.14072.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (2023) Labor force participation rate for women.

- Hegewich Ariane, Heidi Hartmann (2014) Occupational Segregation and the Gender Wage Gap: A Job Half Done. Washington DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

- Artz Benjamin, Ilker Kaya, Ozqur Kaya (2022) Gender Role Perspectives and Job Burnout. The Review of Economics in the Household 20(2): 447-470.

- Fouad Nadya A, Wenhsin Chang, Maggie Wan (2017) Women’s Reasons for Leaving the Engineering Field. Frontiers in Psychology 875: 1-11.

- Jaekel Astrid, Elisabeth St-Onge (2016) Why Women Aren’t Making it to the top of Financial Services Firms. Harvard Business Review.

- Valerio Anna Maria and Katina Sawyer (2016) The Men Who Mentor Women, Harvard Business Review, December 7.

- Chin Stacey, Alexis Krivkovich, Marie Claude Nadeau (2018) Closing the Gap: Leadership Perspectives on Promoting Women in Financial Services, September 6.

- Mannion Mary (2022) How can we address the gender gap in the financial industry. J Morgan Wealth Management.

- Kweilin Ellingrad, Alexis Krivkovich, Marie -Claude Nadeau, Jill Zucker Mannion Mary (2022) Closing the gender and race gap in North American Financial Services. McKinsey & Company.

- Wall Street Journal (2018) Wall Street Wants More Female Traders but Old Perceptions Die Hard, June 14.

- Rogish Alison, Desiree D’Souza, Neda Shemluck (2021) Leadership, Representation, and Gender Equity in Financial Services. Deloitte Insight.

- Gitnux (2024) Market Data Report.

- Stern Charlotta, Guy Madison (2022) Sex differences and Occupational Choice Theorizing for Policy Informed Behavioral Science. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 202: 694-702.

- King Mary, Malin Ortenblad, Jamie J Ladge (2018) What Will It Take to Make Finance More Gender Balanced. Harvard Business Review, December.

-

Susanna Tardi, Alexandros Panayides and Giuliana Campanelli Andreopoulos*. The Persistence of Gender Disparities in Occupational and Promotional Achievement. Iris J of Eco & Buss Manag. 2(1): 2024. IJEBM.MS.ID.000528.

-

Medical sciences, Public administration, Substantial increase, Bureau of labor statistics, Financial analysts, Biological theories, Socialization, Masculinity, Femininity, Individual lives, Public health, Empirical research

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.