Review Article

Review Article

Reconciling GuySuCo’s Economic Legacy with Guyana’s Emerging Petro-Economy

Ashmi Mangal1*, Shenella Benjamin2, and Netra Chhetri3

1School of Entrepreneurship and Business Innovation, University of Guyana, Berbice Campus, Guyana, South America

2Lecturer, Division of Agriculture, University of Guyana, Tain Campus, Guyana, South America

3School for the Future of Innovation in Society, Arizona state University, Arizona, USA

Ashmi Mangal, School of Entrepreneurship and Business Innovation, University of Guyana, Berbice Campus, Guyana, South America

Received Date:July 10, 2025; Published Date: July 23, 2025

Abstract

This paper examines the evolving trajectory of Guyana’s sugar industry against the backdrop of the country’s rapid transformation into a petroeconomy. Once central to national GDP, rural livelihoods, and agrarian identity, the industry has experienced a steep decline in output and relevance. We argue that this decline is not merely economic, but deeply institutional, rooted in colonial and post-independence structuralist development paradigms that have constrained adaptability and innovation. Drawing on Amartya Sen’s capability approach and the Participation and Inclusion Model for Value Chain Development (PIVCD) by the authors, the paper offers a reimagined role for Guyana’s sugar industry as a catalyst for inclusive, resilience-oriented, and innovation-led development. Through the lens of institutional reform and stakeholder agency, we propose a transition away from extractive, top-down models toward decentralized, knowledge-rich, and participatory systems. The analysis contributes policy-relevant insights for repositioning agricultural legacy sectors as strategic platforms for equity and sustainability in resource-rich, rapidly developing economies.

Keywords:Sugar industry, petro-economy, inclusive development, value chain innovation, capability approach

Context

As Guyana enters a new phase of economic transformation, it must find meaningful ways to integrate its agricultural legacy into a broader development strategy shaped by the rise of oil and gas. For centuries, agriculture, especially sugarcane, has not only driven economic production but also shaped the country’s cultural fabric, political movements, and spatial development. From the colonial plantation system to post-independence nationalization, the sugar industry, anchored by GuySuCo (Guyana Sugar Corporation), has long stood as a pillar of rural livelihoods and state-building. Today, however, the emergence of offshore oil reserves, multinational energy partnerships, and a growing service economy are rapidly redrawing the country’s development map. As new wealth and global attention center on oil, the coexistence of old and new sectors brings into sharp focus the risks of economic imbalance, spatial inequality, and policy neglect. The sugar industry, still vital to rural employment, water management, and land governance, cannot simply be left behind. Its future now depends on forward-looking public policy that embraces science and technology, supports diversification, and integrates agriculture into a more inclusive, climate-resilient economic framework. The choices made today will determine whether Guyana’s transition becomes a story of shared prosperity, or one of deepening divides.

Building on this context, we explore the evolving trajectory of Guyana’s sugar industry, a state-owned entity GuySuCo, within the broader dynamics of an emerging oil economy. Rather than viewing this moment as a simple economic shift from agriculture to hydrocarbons, we argue that it marks a more profound transformation, one rooted in institutional realignments, political choices, and cultural renegotiations shaped by the legacy of colonial capitalism. GuySuCo, once the anchor of national economic planning and social cohesion, now operates in the shadow of a rapidly expanding oil sector, one that promises high revenues but also brings volatility, environmental risks, and heightened geopolitical exposure. Understanding the future of GuySuCo in this context is not merely an exercise in sectoral analysis, it is essential to grasping the country’s broader development trajectory. The sugar industry remains deeply embedded in rural livelihoods, landuse systems, and national memory. Its marginalization would not only affect economic indicators but also deepen spatial and social inequalities, particularly in the country’s interior and coastal communities. As such, the central question this paper addresses is both timely and consequential: How can Guyana reconcile these competing worldviews, agrarian and hydrocarbons, extractive and inclusive, to forge development strategies that are not only economically viable, but socially just, environmentally sustainable, and historically informed?

Backbone to Bystander

At its peak, the sugar industry was the backbone of Guyana’s economy. GuySuCo alone accounted for more than 20% of national GDP, employed over 20,000 workers directly, and indirectly sustained tens of thousands more through allied services, community networks, and regional infrastructure [1]. Sugar exports generated the bulk of foreign exchange earnings and underpinned public spending, particularly in rural and coastal regions. Beyond its economic weight, GuySuCo shaped the country’s agrarian identity and played a stabilizing role in national life. Today, however, its contribution has declined significantly, representing less than 2% of GDP [2], and requiring frequent state subsidies to remain operational. This stark decline is not just a reflection of global sugar prices or trade reforms, but of institutional inertia, fragmented leadership, and a failure to inform by science and technology in the face of changing national and global dynamics. As Guyana reorients toward a resource-rich future, the sugar industry must not be dismissed as a relic. Rather, it should be repositioned as a strategic site for inclusive, climate-resilient, and science-driven institutionled transformation, especially if GuySuCo can move from a legacy model of top-down management to one driven by innovation, engagement, value creation, and knowledge co-production.

Shift from Structure to Capability

Sugarcane cultivation in Guyana has historically represented more than an economic activity; it has functioned as a cultural, political, and existential symbol. During the colonial era, sugar occupied a central role in extractive economic models defined by hierarchy, racialized labor, and dependence on external markets [3]. The emergence of state-owned estates under GuySuCo institutionalized this legacy - maintaining productivity through centralized control while reinvesting minimally in local skills, innovation, or value-added initiatives. Despite the postindependence shift toward nationalization and protectionist policies, the industry’s foundational structure remained largely unchanged, exemplifying what Trevor Parfitt [4] critiques as a structuralist development regime - rigid, top-down, and often detached from lived realities.

However, this paper shifts the analytical lens toward Amartya Sen’s [5] capability approach, which reorients the meaning of development away from aggregate economic performance and toward the substantive freedoms. In the context of GuySuCo, this approach underscores the importance of empowering farmers, workers, and local institutions - not simply as labor inputs, but as epistemic agents and innovation partners with the capacity to shape the systems they are embedded in. This reorientation also demands a reconsideration of how innovation is designed and delivered. Rather than treating it as a linear process driven by external expertise, science-based, institution-led innovation becomes a critical tool for capability expansion: enabling stakeholders to access new technologies, strengthen organizational learning, and participate meaningfully in decision-making.

By rooting innovation in context, responsive to agro-ecological variation, cultural knowledge systems, and stakeholder aspirations, GuySuCo can transcend outdated productivity metrics and shift toward inclusive and adaptive value creation. This approach reframes innovation not as the mere introduction of new technologies, but as a collaborative process grounded in the lived realities of farmers, workers, and local communities. It recognizes that resilience cannot be built through uniform solutions; it must emerge from systems that are flexible, responsive, and co-designed with those they are meant to serve.

When institutions invest in locally grounded innovation ecosystems, they do more than modernize production, they unlock latent capabilities across the entire value chain. Farmers gain access to agronomic knowledge tailored to their micro-environments; workers develop new technical and managerial competencies; and communities become active participants in shaping the future of the industry. This inclusive innovation framework also opens space for non-traditional metrics of success: those that reflect improvements in well-being, equity, and environmental stewardship, rather than output alone. In this way, innovation becomes not a technical fix, but a developmental catalyst, transforming sugar from a legacy industry marked by hierarchy and dependency into a platform for empowerment, resilience, and broad-based prosperity. If GuySuCo can align institutional reform with capability expansion, it can play a pivotal role in advancing Guyana’s broader goals of sustainable development and inclusive economic transformation.

Politics, Policy, and Participation

Continuing from the deeply human aspects of the sugar industry’s challenges, it is essential to acknowledge the complex interplay between policy, research, and politics that shapes decision-making in high-stakes environments. As Fenwick [6] observe, in politically charged contexts, research evidence is often filtered through the lens of electoral strategy, where findings are more likely to be accepted if they align with the interests of voting constituencies. This tension is evident in recent government actions, such as the reopening of the Rose Hall Sugar Estate, which, while welcomed by many, has also been interpreted by some as influenced more by political considerations than by objective assessments of the industry’s structural needs.

While the needs of all stakeholders are critical, they can sometimes become entangled with political motives, resulting in actions informed more by electoral calculus than by evidencebased policy or the industry’s intrinsic needs. Such dynamics must be addressed with transparency and a firm commitment to the broader public good if Guyana’s sugar industry is to achieve a desirable transition. Navigating the nuanced terrain between policy implementation and political influence is undoubtedly a formidable challenge. Yet, insights from both Amartya Sen’s capability approach and Elinor Ostrom’s work on institutional diversity offer a valuable pathway forward. Sen (1999) urges us to assess development in terms of expanding real freedoms and opportunities for individuals to shape their lives. In GuySuCo’s case, this means acknowledging that the current managerial structure often limits the agency of vulnerable stakeholders, employees, suppliers, and community members, by treating them as logistical variables rather than as knowledge holders and innovation partners.

Ostrom’s research [7,8] complements this view by demonstrating that inclusive, polycentric governance systems, those that enable multiple centers of decision-making, can outperform top-down bureaucracies, particularly in governing resources and complex institutional environments. Applied to GuySuCo, this suggests that durable reform will require more than administrative tweaks; it demands a shift toward co-governance, where diverse actors jointly shape rules, monitor outcomes, and adapt appropriately. Reframing workers and communities as co-producers of GuySuCo’s pathway forward, rather than passive recipients of policy, is essential to building a more inclusive, resilient, and adaptive sugar-belt economy.?

Navigating the New Economy

The discovery of offshore oil and Guyana’s rapid emergence as a petro-economy have shifted the country’s development narrative. Where sugar once symbolized national identity and resilience, it is now increasingly seen by some as a relic of inefficiency and colonial legacy. In contrast, oil is framed as Guyana’s gateway to prosperity, innovation, and global relevance. This reframing carries profound implications, not only for national economic priorities but also for the narratives that legitimize them. Traditional agriculture risks being discursively marginalized, its importance diminished by technocratic and extractivist logics that prioritize economic growth over equity and inclusion. As Ferguson [9] warns in his critique of petro-economies, such narratives can entrench exclusion, creating “enclaves of modernity” that leave longstanding institutions and rural livelihoods behind.

Nevertheless, the pivot to oil is not without risk. As Karl (1997) warns in her study of petro-states, without careful policy design, oil wealth can entrench institutional fragility, crowd out non-extractive sectors, and compromise democratic responsiveness, distort economic priorities, and weaken other productive sectors like agriculture. Recognizing these vulnerabilities, Guyana has begun investing in the mechanization, automation, and diversification of both the sugar industry and the broader agricultural sector to secure its long-term economic and social stability. However, it must be guided by evidence-based policy and a holistic understanding of stakeholder needs to ensure that development remains socially just, economically viable, and not merely politically expedient. While mechanization may appear to be a response to labor shortages in an increasingly labor-intensive sector, a deeper analysis reveals a more complex picture. Sugar workers are aware of the European Union’s sugar reform, the resulting loss of preferential access, and the downsizing of GuySuCo. They are also attentive to the implications of the Transformational Plan and the land transformation policy’s potential impact on the future of the sugar estate (e.g. Rose Hall). Their insights reflect a grounded understanding of the political economy of transition, one that must not be ignored.

Attitudes and behaviors shape culture, and culture in turn shapes attitudes and behaviors, in a reciprocal cause-and-effect relationship (Fernandes, 2004). Given the widespread public support for the reopening of the estate, it is imperative that the government and the estate’s management committee convene a dialogue with stakeholders to collaboratively develop a strategy that benefits all parties. Considering the projected Regional Transformational Plan [10], it is prudent for the Government of Guyana and GuySuCo’s management to engage directly with stakeholders and listen to their concerns. We believe they understand that the nation’s sugar industry will not return to its previous levels of sugar production, which will inevitably impact their ability to earn a livable wage. As Singh (2021) notes, a national transformation strategy is necessary, as the industry alone cannot revitalize entire communities. Consequently, many workers will be drawn to more lucrative sectors in search of better livelihoods. In response, the industry must consider two key paths forward: mechanizing operations to substitute for increasingly scarce and costly labor, consistent with the induced innovation hypothesis [11], and/or diversifying into higher-value activities that offer better-paying and more varied employment opportunities in line with emerging market demands [12].

Case for Reopening Rose Hall Estate

The Rose Hall Sugar Estate, located on the lower East Bank of the Canje River, historically served as a key transshipment hub for sugar produced in East Berbice. Beyond its industrial function, the estate played a critical role in environmental stewardship, particularly through the management of the Canje River and the Torani Canal, which ensure a reliable water supply for agricultural production along the Corentyne Coast. The 2021 flooding of the Corentyne Coast underscored the estate’s importance in regional water management. While some reports attributed the flooding to excessive rainfall and others to the Neighborhood Democratic Council’s (NDC) failure to fulfill its responsibilities (Kaieteur News, 2021), the event brought renewed attention to the ecological vacuum left by the estate’s closure. In response, the government allocated GYD 7.8 billion in flood relief to Region Six, an amount that far exceeded the GYD 1.195 billion invested in rebuilding the Rose Hall processing facility [13].

This comparison highlights the multifaceted value of the estate. Its social and environmental contributions far surpass its monetary output. As Peet and Hartwick (2015) argue, development should enhance quality of life, not merely increase economic output. To residents of the sugar belt, Rose Hall is more than a place of employment, it is a symbol of stability, cultural continuity, and social cohesion. Development theorists such as Battersby and Roy (2017) emphasize that the most effective interventions are those aligned with local norms, knowledge systems, and lived practices. Beyond its productive function, the Rose Hall Estate holds deep social significance, nurturing the everyday rhythms, hopes, and cohesion of the surrounding community.

The successful revitalization of the Rose Hall Estate and the upliftment of surrounding communities will require the Government of Guyana to adopt a development approach rooted in inclusive stakeholder engagement. This entails active and inclusive engagement with all stakeholders, sugar workers, residents, civil society actors, and experts, in planning, implementation, and monitoring. As Sen (1999) reminds us, development is not just about income, but about the freedom to lead lives people value. Beyond wages, people seek the right to participate in decisions that shape their futures, wellbeing, and dignity. The path to revitalization, therefore, must be paved with more than good intentions. It must rest on inclusive dialogue, shared governance, and institutional transparency. Only through this collective empowerment can Guyana’s sugar industry be transformed, ensuring that the fruits of progress are not only harvested but equitably shared by all who labor and hope have long nurtured its fields.

Structuralism to Stakeholders Engagement

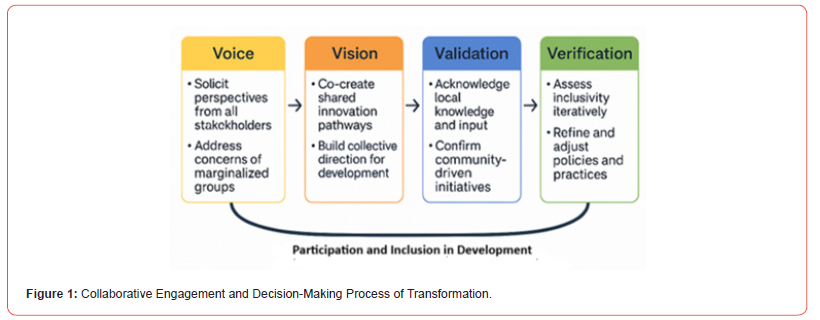

We believe that the Participation and Inclusion Model for Value Chain Development (PIVCD) offers a grounded response to this challenge (Figure 1). Essentially, the PIVCD model represents a form of social innovation which Derrida and Foucault might call a deconstructive approach to development [14]. It resists closure and refuses the tendency to fix meaning or identity. Instead, it invites difference, complexity, and coexistence, reframing farmers and workers not as logistical actors but as epistemic agents with a stake in shaping the systems that affect their lives.

The model comprises four interlinked stages: Voice, Vision, Validation, and Verification, each representing a shift from topdown governance toward distributed agency and co-creation. In doing so, PIVCD not only critiques the structural failings of GuySuCo, such as its centralized control, inefficiency, and marginalization of farmers, but also proposes a context-sensitive alternative for revitalizing agricultural value chains. The model is designed to ensure that agriculture is not displaced by the oil economy but instead integrated into a broader, inclusive vision of sustainable transformation. Importantly, this approach aligns with global shifts in development thinking. As Chambers [15] noted, participatory and inclusive strategies are not only ethical, they are effective. Development fails when it ignores the very people it claims to serve [16]. Through the application of deconstruction as praxis, Guyana could resist the totalizing logic of both colonial structuralism and neoliberal oil capitalism, forging instead a science-based, innovation-driven, and pluralistic development trajectory [17].

Conclusion

Guyana’s development cannot be simply framed as a binary choice between sugar or oil, the past or the future, tradition or modernity. The way forward requires rethinking development as an inclusive, dynamic, and co-created process, one that recognizes complexity and empowers people, rather than imposing one-sizefits- all models. While structuralist paradigms offered a semblance of order, they often did so by silencing diverse voices and obscuring lived realities. In contrast, development guided by Amartya Sen’s capability approach places human agency and dignity at its core, shifting the measure of progress from aggregate outputs to expanded opportunities.

This vision demands more than institutional reform; it calls for science-based, context-sensitive innovation, participatory governance, and a deliberate effort to integrate local knowledge into national policy frameworks. By investing in inclusive value chains, diversifying rural economies, and fostering cross-sectoral collaboration, Guyana can build a more resilient future, one that uplifts both traditional sectors and emerging industries. GuySuCo, if repositioned as a platform for capability enhancement, stakeholder engagement, and institutional learning, can become a model for what post-extractive development might look like. Its transformation is not simply about rescuing a declining industry but about demonstrating that legacy sectors can still serve as engines of inclusive growth in the 21st century. So, the true test for Guyana will not be how fast it grows, but how widely and justly that growth is shared. If done right, Guyana’s development path can offer a powerful alternative to the extractive trajectories that have failed so many resource-rich nations, an example of a country that did not trade equity for efficiency, nor identity for modernization, but found a way to reconcile both in pursuit of a future that is prosperous, participatory, and proudly its own.

References

- Davis BH, Piggot AJ (2015) Future of GuySuCo _Commission of Inquiry.

- World Bank (2023) Guyana Economic Update: Leveraging Resources for Inclusive Growth. Washington, D.C., World Bank Group.

- William R (2006) Plantation economies and the Caribbean legacy. Caribbean Quarterly 52(3-4): 12-28.

- Parfitt T (2002) The End of Development? Modernity, Post-modernity and Development. Pluto Press.

- Sen A (1999) Development as Freedom. Oxford University Press.

- Fenwick T, Mangez E, Ozga J (2013) Governing knowledge: Comparison, knowledge-based technologies and expertise in the regulation of education. Routledge.

- Ostrom E (1990) Governing the commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ostrom E (2005) Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ferguson J (2005) Global shadows: Africa in the neoliberal world order. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Government of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana (2023) Guyana second voluntary national review of the Sustainable Development Goals. Ministry of Finance.

- Hayami Y, Ruttan VW (1971) Agricultural development: An international perspective. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- IFAD (2016) Rural Development Report 2016: Fostering inclusive rural transformation. Rome: International Fund for Agricultural Development.

- Guyana Chronicle (2021) Guyana Chronicle.

- Dixon DP, Jones JP (2005) Poststructuralism and the production of geographical knowledge. Social & Cultural Geography 6(1): 53-69.

- Chambers R (1997) Whose reality counts? Putting the first last. Intermediate Technology Publications.

- FAO (2014) The State of Food and Agriculture: Innovation in family farming. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Chambers R (2023) Rural development: Reflections and reforms. Institute of Development Studies.

-

Ashmi Mangal*, Shenella Benjamin, and Netra Chhetri. Reconciling GuySuCo’s Economic Legacy with Guyana’s Emerging Petro-Economy. Iris J of Eco & Buss Manag. 3(1): 2025. IJEBM.MS.ID.000555.

-

Sugar industry; petro-economy; inclusive development; value chain innovation; capability approach; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.