Research Article

Research Article

Exploring the Interplay: Organizational Types and Leadership Styles in Contemporary Dynamics

Anderson Santanna, Professor at Fundação Getúlio Vargas FGV-EAESP, Brazil.

Received Date:November 20, 2023; Published Date:March 01, 2024

Abstract

This article explores the dynamic landscape of leadership theories, spanning classical to contemporary perspectives. From Lewin’s field theory to Fiedler’s contingency model, transactional, and transformational leadership, the journey leads to adaptive leadership and beyond. The symbiotic relationship between leadership styles and organizational structures is examined, emphasizing the need for a context-specific approach. Critiques from scholars like Mary Uhl-Bien prompt a shift towards horizontal, inclusive, shared, enabling and distributed leadership paradigms, aligning with complexity leadership theory. The interdisciplinary insights of physicists like Penrose and psychoanalysts like Winnicott enrich the discourse. Penrose challenges traditional views of artificial intelligence, while Winnicott’s psychoanalytic concepts offer a lens to understand the emotional dimensions of leadership in decentralized structures. As the 21st-century leadership landscape unfolds, embracing diversity, fostering innovation, and nurturing authentic relationships emerge as imperatives for organizational effectiveness.

Keywords:Leadership; Leadership styles; Post-modern leadership; Adaptive leadership; Organizational types

Introduction

The field of organizational studies has meticulously explored and categorized diverse organizational types, tracing its roots back to the early 20th century when scholars recognized the necessity for systematic frameworks [1]. From Barnard’s emphasis on informal aspects [2] to the contingency theory spearheaded by Burns and Stalker [3], Woodward [4], and Lawrence and Lorsch [5], the evolving understanding of organizational structures has been shaped by pivotal contributions. As one delves into the mid-20th century, influenced by Lewin’s field theory, authors such as Burns and Stalker [3], alongside Lawrence and Lorsch [5], expanded contingency theory by introducing concepts such as mechanistic and organic structures, highlighting organizations’ adaptability to different contexts. The subsequent decades witnessed a shift towards studying organizational culture, with Schein’s work emphasizing shared values and beliefs [6]. In the dynamic landscape of the 21st century, characterized by technological advancements and globalization, organizational arrangements have undergone profound transformations [7]. The rise of digital business, virtual organizations, network structures, and the gig economy challenges traditional configurations [8-12]. In this regard, scholars like Uhl- Bien [13], Mintzberg [14], and Morgan [15] have contributed significantly to understanding the emergent forms of organizations. Amidst this complexity, this article aims to unravel the nuanced connections between organizational configurations and the diverse array of leadership styles [16,17].

The concept of leadership is inherently polysemic, with almost as many definitions as there are authors. However, despite this diversity, certain common points can be observed across different definitions. Firstly, leadership is often understood as a form of power, representing the capacity to influence [18]. Secondly, it is viewed as directly associated with the ability to bring about transformation [18,19]. Finally, leadership is recognized as the capacity to navigate contexts and understand people, aiming to identify the most suitable person, situation, and moment [20-22]. These fundamental characteristics of leadership support perspectives that perceive it as a relational phenomenon and as a competency capable of effectively balancing environmental and personal factors, as advocated by one of the pioneers in categorization leadership studies, Kurt Lewin [1,20]. In the context of contemporary dynamics, where traditional boundaries blur and organizational forms become increasingly fluid, understanding how different leadership styles intersect with varied organizational types becomes imperative [8-10, 23,24]. As one embarks on this analysis, our purpose is twofold. First, one seeks to offer a comprehensive analysis of contemporary organizational configurations, considering structural, technological, cultural, and environmental factors [5,6,25,26]. Second, one aims to shed light on how leadership styles navigate the intricacies of post-modern dynamics, providing insights crucial for leaders and scholars alike in understanding and navigating the challenges and opportunities of the contemporary professional landscape [13,15].

Organizational Types

The 1930s marked the formative stages of organizational studies, and during this time, Barnard’s work stood out for its emphasis on the informal aspects of organizations [2]. In his influential work, “The Functions of the Executive”, Barnard recognizes the significance of informal social relationships and communication channels that go beyond formal roles, shaping organizational dynamics. Barnard’s conceptual framework suggests a departure from the traditional focus on structure, highlighting the importance of understanding organizations through both formal and informal lenses [2]. He introduces the idea of a “zone of indifference”, acknowledging that individuals within organizations accept authority up to a certain point without questioning, adding a psychological dimension to organizational typology. His groundbreaking emphasis on communication as a critical function of executives and organizations underscores its essential role in achieving organizational goals and maintaining cooperation among members [2]. While Barnard does not provide a specific typology, his insights lay the groundwork for future scholars to explore the interplay between formal and informal elements within organizations and anticipate later theories delving into cultural and behavioral aspects [2]. Moving to the mid-20th century, Woodward [4], another influential organizational theorist, made substantial contributions by focusing on the relationship between technology and organizational structure. Through empirical research across industries, Woodward identifies three primary organizational types based on the complexity of the production process, commonly known as “Woodward’s typology” [4].

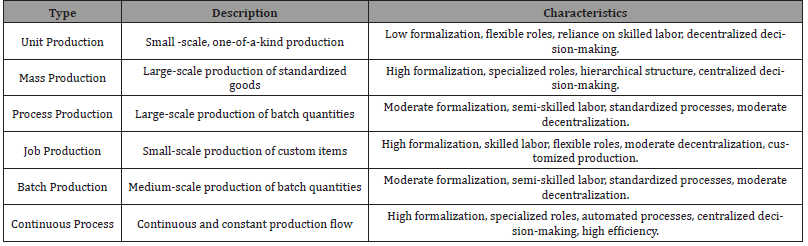

In industries with small-batch or unit production, emphasizing customization and flexibility, Woodward observes a decentralized structure with a high degree of employee skill and autonomy - termed unit production systems [4]. Mass production systems, characterized by large-scale and standardized processes, exhibit a more centralized and hierarchical structure to ensure efficiency. The third type, process production systems, found in continuous or process production industries, displays a hybrid structure combining centralization and decentralization to manage continuous production flow [4]. Table 1 outlines Woodward’s typology, detailing types, descriptions, and characteristics. Woodward’s contributions are not only significant for introducing a typology based on technology but also for emphasizing the importance of aligning organizational structure with the requirements of the production process. Her findings challenge the prevailing notion that one-size-fits-all organizational structures can be universally applied [4].

Table 1:Woodward’s typology.

Source: Elaborated by the author.*/

Moreover, Woodward’s research lays the groundwork for contingency theory in organizational studies, suggesting that the optimal organizational design depends on the external environment, particularly the technological demands of the industry [4]. In the decades following Woodward’s research, scholars expanded on contingency theory, considering additional factors such as environmental uncertainty and organizational size. However, Woodward’s contributions remain foundational in the broader conversation about how organizations adapt their structures to fit the demands of their contexts [4]. In the realm of contingency theory, Burns and Stalker mark a significant departure from earlier theories by introducing the concept of organic and mechanistic organizations. Their groundbreaking research aims to understand how different organizational structures respond to challenges posed by the external environment [3]. The key distinction in Burns and Stalker’s studies lies in their characterization of organizations as either organic or mechanistic. In stable and predictable environments, the authors observed the prevalence of mechanistic structures. These organizations exhibit a hierarchical and rigid structure with clearly defined roles and responsibilities. Decisionmaking is centralized, and communication follows formal channels. Mechanistic organizations thrive in environments where tasks are routine and predictable [3].

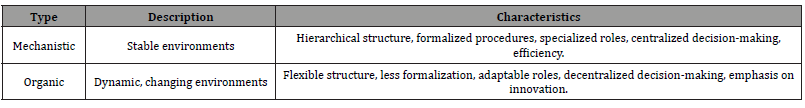

In contrast, organic structures are identified in dynamic and unpredictable environments. According to Burns and Stalker [3], these organizations embrace flexibility and decentralized decision-making. Communication is more informal, and roles are adaptable to changing circumstances. Organic organizations excel in environments where innovation and adaptability are critical. As displayed in Table 2, Burns and Stalker’s research emphasizes the alignment of organizational structure with the demands of the external environment. In dynamic environments, the flexibility of organic structures allows for quicker adaptation to change, while in stable environments, the rigidity of mechanistic structures provides efficiency and control [3].

Table 2:Mechanistic vs. Organic Structures.

Source:Elaborated by the author

Burns and Stalker’s typology lays the foundation for contingency theory, suggesting that organizational effectiveness is contingent upon the fit between an organization’s structure and the demands of its environment. This perspective challenges earlier notions of universal organizational principles and emphasizes the need for context-specific design [3]. Furthermore, it recognizes that organizations might exhibit characteristics of both organic and mechanistic structures simultaneously, leading to the concept of a “mixed” or “contingency” form. This nuanced understanding acknowledges that real-world organizations often face a complex interplay of stable and dynamic environmental factors. In the late 1960s, Lawrence and Lorsch [5] expanded the understanding of how organizations adapt to external environments. Unlike previous studies that focused primarily on internal factors, the authors explore the dynamic relationship between organizations and their external environments. They introduce the concept of differentiation and integration as key mechanisms through which organizations respond to environmental challenges.

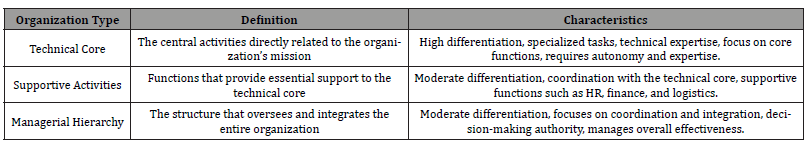

According to Lawrence and Lorsch [5], organizations confront two essential imperatives: the necessity to differentiate or specialize in response to diverse external demands and the requirement to integrate or coordinate these specialized activities to uphold overall effectiveness. This conceptualization leads to the identification of three distinct organizational forms: the technical core, supportive activities, and the managerial hierarchy, as summarized in Table 3 [5].

Table 3:Lawrence and Lorsch Typology.

Source:Elaborated by the author.

Based on Lawrence and Lorsch’s categories, organizations must find a delicate equilibrium between differentiation and integration to adeptly navigate their external environments [5]. In dynamic and uncertain contexts, a greater emphasis on differentiation becomes imperative as organizations strive to adapt to diverse challenges. Conversely, in stable environments, a heightened focus on integration ensures efficiency [5]. This nuanced approach underscores the importance of aligning organizational structure with the demands of the external environment. Unlike earlier categorizations that fixated on singular aspects, Lawrence and Lorsch’s model considers the intricate interplay between internal and external factors [5]. Their perspective significantly contributes to contingency theory, emphasizing the rejection of a universal organizational structure. Instead, organizations must tailor their structures to the specific demands of their external context. The delicate balance between differentiation and integration emerges as pivotal in achieving organizational effectiveness [5]. Shifting the focus to Schein [6], his profound exploration of organizational culture advances our understanding of typologies. Emphasizing the pivotal role of culture in shaping organizational behavior, Schein delineates three levels of organizational culture. Firstly, he identifies artifacts and symbols - visible elements like structures and rituals representing deeper cultural values. Secondly, espoused values, officially stated beliefs often present in mission statements, may or may not align with actual behavior. Lastly, Schein [6] delves into basic assumptions, and deeply embedded, often-unconscious beliefs guiding decision-making within an organization.

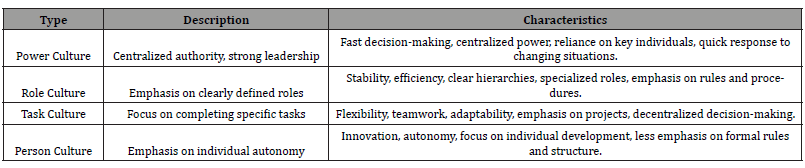

Table 4:Schein’s culture archetypes.

Source:Elaborated by the author.

Within the framework of organizational culture, Schein [6] outlines four common archetypes. A power culture, characterized by a strong central authority, facilitates quick decision-making but may lead to dependence on key individuals. In role cultures, clarity in roles and responsibilities is paramount, emphasizing stability and efficiency but potentially hindering adaptability. Task cultures prioritize project completion, fostering flexibility and teamwork but facing challenges in maintaining coherence. Person cultures prioritize individual autonomy and innovation but may struggle with coordination (Table 4). Schein’s work not only aids in diagnosing existing cultures but also provides valuable insights for shaping and changing cultures to align with organizational goals. His contributions remain foundational for scholars and practitioners navigating the intricate interplay of values and assumptions within organizations [6]. Concomitantly, Mintzberg [27] has significantly shaped our understanding of organizational structures through his work on organizational configurations. His insights challenged conventional views that portrayed organizations as neatly designed and hierarchical entities.

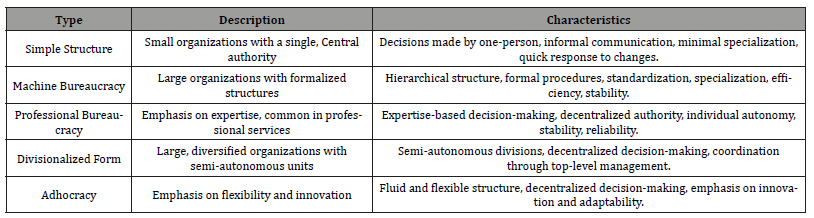

The author proposes the concept of organizational configurations, suggesting that organizations adopt a combination of structural elements to address diverse needs. He identifies five key organizational configurations or structural archetypes, each suited to different contexts [27]. The simple structure, characterized by centralization of authority and minimal formalization, is typical of small organizations with swift decision-making under a single leader. Machine bureaucracy, on the other hand, embodies a highly formalized structure with clear hierarchies, suitable for stable and routine environments [27]. In settings where expertise is crucial, professional bureaucracies emerge, decentralizing decisions to experts and relying on professional knowledge. Larger, diversified organizations often adopt the divisionalized form, featuring semiautonomous units with functional structures, providing flexibility and responsiveness [27]. Furthermore, Mintzberg [27] introduces the concept of adhocracy for dynamic and innovative environments. Adhocracies lack formal structure, emphasizing employee empowerment, creativity, and innovation. The insights provided by Mintzberg’s organizational configurations, as detailed in Table 5, offer a comprehensive understanding of diverse organizational structures.

Table 5:Mintzberg’s Organizational Configurations..

Source:Elaborated by the author..

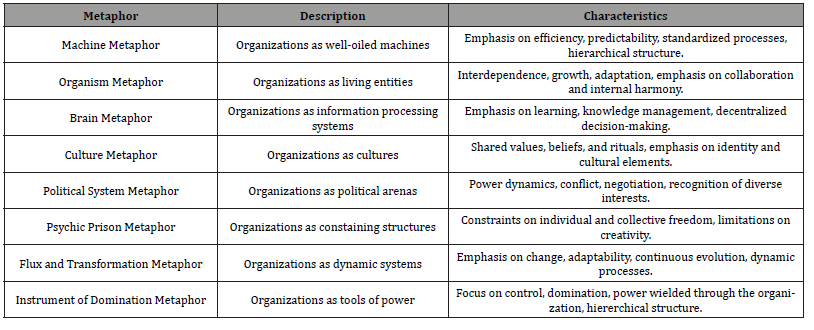

Mintzberg’s studies emphasize that organizational structure is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Organizations select configurations based on their context, strategy, and environmental demands. He underscores the importance of understanding the emergent nature of organizational structures and acknowledging their evolution over time in response to internal and external factors [27]. Concomitantly, Morgan [15] introduces the concept of organizational metaphors as a powerful tool for understanding various organizational forms. He presents eight metaphors, each offering a distinct perspective on organizations. The machine metaphor likens organizations to well-oiled machines, emphasizing efficiency and predictability. The organism metaphor draws from biological analogies, portraying organizations as living entities with interdependence, growth, and adaptation.

In the brain metaphor, organizations are viewed as information processors, emphasizing learning and the importance of knowledge in decision-making. The culture metaphor focuses on shared values, rituals, and cultural elements shaping organizational identity [15]. The political system metaphor views organizations as arenas of power and negotiation, reflecting diverse interests and political maneuvering. The psychic prison metaphor suggests that organizations can act as constraining structures, limiting individual and collective freedom [15]. Morgan [15] also introduces the flux and transformation metaphor, emphasizing the dynamic nature of organizations in a constant state of change. The instrument of domination metaphor highlights issues of control and domination, portraying organizations as tools through which power is wielded.

Crucially, the author argues that each metaphor provides a unique lens, influencing how individuals perceive and navigate the complexities of organizational life. He advocates for the use of multiple metaphors to achieve a richer and more holistic understanding of organizational dynamics [15]. In essence, Morgan’s exploration of organizational metaphors expands the repertoire of perspectives for analyzing and interpreting organizational behavior and structure. His work encourages a nuanced and multi-dimensional approach to understanding the diverse facets of organizational life [15].

Table 6:Morgan’s Organizational Metaphor.

Source:Elaborated by the author.

Morgan’s Organizational Metaphor, as encapsulated in Table 6, provides a fascinating exploration of how organizations can be metaphorically conceptualized. Morgan’s exploration of organizational metaphors acknowledges that these perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Organizations may embody multiple metaphors simultaneously, reflecting the complexity and diversity of organizational life. His work encourages a more fluid and dynamic understanding of organizational identity, recognizing the multiple layers of meaning and interpretation that shape organizational behavior [15].

Beyond traditional perspectives, Morgan [15] incorporates postmodern and symbolic lenses. He urges scholars and practitioners to recognize the symbolic aspects of organizational life, emphasizing the role of meaning and identity in shaping behavior. In doing so, Morgan’s studies on organizational typology provide a rich and comprehensive framework that captures the diverse ways organizations are conceptualized, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of organizational dynamics. Other influential authors in organizational post-modern studies, such as Clifford Geertz, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, Pierre Bourdieu, Jacques Lacan, and Mary Jo Hatch, among others, bring important contributions to the understanding of language and symbols in organizational discourse. Collectively, these scholars expand the intellectual landscape, offering alternative perspectives that enrich our understanding of the intricate dynamics within organizations.

Leadership Styles

The exploration of leadership styles within the realm of organizational behavior also has a rich and evolving history. The journey began with the emergence of trait theories in the early 20th century, seeking to identify inherent qualities that distinguished effective leaders [28]. The focus is on identifying a set of characteristics, such as decisiveness, intelligence, and charisma, associated with effective leaders. Moving forward, the 1940s witnessed the rise of behavioral theories, shifting the spotlight from innate traits to observable behaviors. During this period, Kurt Lewin played a crucial and foundational role in shaping leadership studies through his groundbreaking field theory. Lewin’s contributions revolutionized the understanding of leadership by introducing the concept of the “field”, emphasizing the dynamic interplay between individuals and their environments [1,29-31].

Lewin’s field theory proposed that behavior is a function of both the person and the environment, acknowledging the significance of situational factors in influencing leadership dynamics [1,32]. This perspective laid the groundwork for the behavioral approach to leadership, which sought to identify and analyze observable behaviors that contribute to effective leadership. Incorporating Lewin’s insights, behavioral theories explored the role of leadership behaviors in various contexts [32]. Researchers began to focus on identifying specific behaviors associated with effective leadership, paving the way for the development of leadership models that emphasized the importance of actions and interactions within organizational settings.

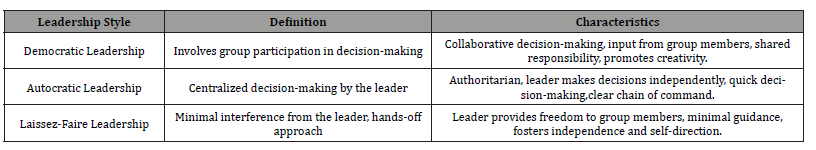

In this regard, Lewin, Lippitt, and White [32] delve into democratic, autocratic, and laissez-faire leadership styles, examining how these approaches influenced group dynamics and productivity [32]. As a result, they contribute significantly to the understanding of leadership styles. Their typology delineates three fundamental leadership styles: autocratic, democratic, and laissez-faire. Autocratic leadership is characterized by a leader who independently makes decisions and retains full control over the group or organization. This style involves the leader exercising authority, giving specific instructions, and expecting compliance without seeking input from the group [32]. On the other hand, democratic leadership involves group participation in decision- making. In this style, the leader facilitates discussion and collaboration, aiming for inclusive decision-making by gathering input from team members. This approach values the collective wisdom of the group [32].

Laissez-faire leadership, the third style, adopts a hands-off approach. Here, the leader provides minimal guidance, allowing the group to make decisions independently. This style is characterized by the leader taking a backseat role, offering little direction, and granting team members the freedom to make decisions autonomously [32]. Table 7 summarizes the main characteristics of this model.

Table 7:Lewin’s Perspective on Leadership.

Source:Elaborated by the author..

Lewin, Lippitt, and White’s model recognizes the impact of leadership styles on group dynamics and productivity. The autocratic style is efficient in situations requiring quick decisions, while the democratic style fosters collaboration and group satisfaction through inclusive decision-making. The laissez-faire style, effective with highly skilled and motivated groups, can pose challenges in other contexts due to the minimal guidance provided [32].

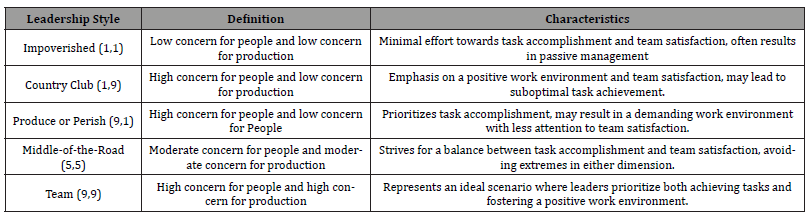

In this regard, Lewin’s work serves as a foundational framework for later theories on leadership and group dynamics. His typology underscored the significance of considering social dynamics and decision-making processes within organizations, influencing subsequent research on effective leadership styles [32]. The 1950s brought forth the managerial grid model by Blake and Mouton [33], introducing a two-dimensional framework that assesses leadership based on concern for people and concern for production. The model, presented as a grid, assigns scores along these dimensions to help identify various leadership styles. One extreme on the grid is the “impoverished” style (1,1), characterized by low concern for both people and production. Leaders adopting this style typically exert minimal effort in achieving tasks and attending to the needs of their team, resulting in passive management [33]. Conversely, the “country club” style (1,9) places a high emphasis on concern for people but a low emphasis on production. Leaders employing this style prioritize creating a positive work environment and fostering team satisfaction but may neglect achieving organizational goals [33].

The “produce or perish” style (9,1) represents high concern for production but low concern for people. Leaders following this style focus on accomplishing tasks efficiently, often at the expense of building positive interpersonal relationships within the team [33]. The “middle-of-the-road” style (5,5) seeks a balance between concern for people and concern for production. Leaders adopting this style aim to achieve a moderate level of task accomplishment while maintaining a reasonable level of team satisfaction. This balanced approach is an attempt to avoid the extremes of either dimension [33]. The ideal leadership style according to Blake and Mouton [33] is the “team” style (9,9). This style represents a high concern for both people and production. Leaders who embrace this approach prioritize both achieving tasks and fostering a positive work environment, recognizing the interdependence of these factors. Table 8 details the leadership styles as per Blake and Mouton’s managerial grid model, encompassing their definitions and distinctive features.

Table 8:Blake and Mouton’s Managerial Grid Model.

Source:Elaborated by the author..

According to Table 8, the numerical values (1 to 9) on the grid represent the intensity of concern along each dimension, offering insights into a leader’s behavioral tendencies [33]. By emphasizing the importance of balancing concern for people and concern for production, the model contributes to the development of effective and adaptive leadership practices within organizations [33]. As the organizational landscape evolved, contingency theories emerged in the 1960s, emphasizing the situational nature of effective leadership. Fiedler’s contingency model suggests that the effectiveness of leadership styles depends on the interplay between leadership style and situational favorableness [34]. Crafted by Fiedler in the 1960s, Fiedler’s contingency model represents a milestone in comprehending leadership efficacy amid diverse situational landscapes. The model posits that a leader’s effectiveness hinges on the interplay between their inherent leadership style and the favorability of the situation [34].

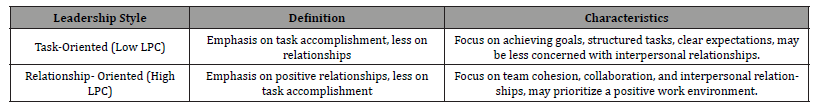

In practice, two primary leadership styles take center stage: task-oriented (low LPC) and relationship-oriented (high LPC). Task-oriented leaders prioritize task accomplishment, while relationship-oriented leaders emphasize positive interpersonal dynamics within the team. The assessment of a leader’s predominant style is facilitated through the least preferred coworker (LPC) questionnaire [34].

The effectiveness of these styles is contingent upon the favorability of the situation, gauged by three key situational factors. Leader-member relations measure the trust and confidence followers have in their leader, task structure evaluates the clarity and routine of tasks, and position power signifies the leader’s authority and influence [34]. In highly favorable situations characterized by good leader-member relations, clear task structure, and substantial position power, both task-oriented and relationship-oriented leadership styles can prove effective. Conversely, in less favorable situations, the fit between the leader’s style and the context becomes pivotal for organizational effectiveness [34].

In situations of low favorability, a task-oriented leader may excel by providing clear direction and structure. In moderately favorable contexts, a relationship-oriented leader might shine by fostering positive connections, even in the absence of a clear task structure [34]. Overall, Fiedler’s contingency model underscores the imperative of comprehending and adapting leadership styles based on the intricacies of the situation. It acknowledges the absence of a one-size-fits-all leadership approach, highlighting that the alignment between a leader’s style and the situational demands is decisive in determining leadership effectiveness [34]. Table 9 provides an overview of leadership styles based on Fiedler’s contingency model, outlining their definitions and key attributes.

Table 9:Fiedler’s Contingency Model.

Source:Elaborated by the author..

In summary, this model posits that the effectiveness of a leadership style is contingent on the leader’s LPC (Least Preferred Coworker) score and the favorability of the situation. The leader’s LPC score reflects their natural inclination towards task-oriented or relationship- oriented behavior [34]. In a favorable situation, where there are good leader-member relations, task structure, and position power, both leadership styles can be effective. However, in unfavorable situations, the leader’s effectiveness depends on the match between their LPC orientation and the situation [34]. It is important to note that Fiedler’s model suggests that leaders have a preferred or dominant style that may be more effective in certain situations, emphasizing the importance of aligning leadership styles with the characteristics of the environment [34]. Introduced in 1977, Hersey and Blanchard’s situational leadership theory, posits that effective leadership is contingent upon the interplay between the leader’s behavior and the developmental level of the followers.

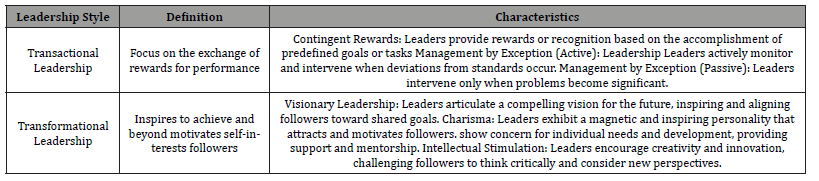

The model emphasizes the adaptability of leadership styles, suggesting that there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Instead, leaders should assess the readiness and maturity of their followers and adjust their leadership style accordingly [22]. The four leadership styles proposed by Hersey and Blanchard [22] include directing, coaching, supporting, and delegating, each catering to different levels of follower competence and commitment. This theory underscores the dynamic nature of leadership, encouraging leaders to be flexible and responsive to the evolving needs and capabilities of their team members [22]. The situational leadership theory has had a significant impact on leadership studies, offering a practical framework for leaders to enhance their effectiveness in diverse and changing contexts [35-37]. The 1980s witnessed the advent of transformational and transactional leadership theories. Burns [18,38] introduces the concept of transformational leadership, highlighting leaders who inspire and motivate followers to achieve beyond their self-interests. On the other hand, Bass [19] expanded on this with transactional leadership, focusing on the exchange of rewards for performance.

Transactional and transformational leadership represent two distinct paradigms within the realm of leadership theories, each offering unique approaches to motivating and guiding followers [18,19]. Transactional leadership revolves around the exchange of rewards and punishments to motivate followers. In this paradigm, leaders establish clear expectations and standards, and followers are rewarded for meeting these expectations or penalized for falling short. Transactional leaders are often task-oriented, focusing on the day-to-day operations and ensuring that organizational goals are met [18,19,39]. Key characteristics of transactional leadership include contingent rewards, where followers receive recognition or incentives based on their performance; and management by exception, which involves the leader intervening when deviations from established norms occur. Transactional leaders provide structure and clarity, making them effective in stable and predictable environments where routine and adherence to established procedures are crucial [18,19,39]. In contrast, transformational leadership transcends traditional transactional exchanges. Transformational leaders inspire and motivate followers to achieve beyond self-interests. They articulate a compelling vision for the future, foster a sense of shared purpose, and empower followers to think creatively and innovate. Transformational leadership emphasizes individualized consideration, intellectual stimulation, and charisma [18,19,39]. Individualized consideration involves personalized support and mentorship for each follower, fostering a positive and supportive work environment. Intellectual stimulation encourages creativity and critical thinking, challenging followers to explore new perspectives and ideas. Charisma, a hallmark of transformational leadership, enables leaders to create a magnetic and inspiring presence that captivates and motivates followers [18,19,39]. Table 10 elucidates the leadership styles as per transactional and transformational perspectives, encompassing their definitions and distinctive features.

Table 10:Transactional Vs. Transformational Leadership

Source:Elaborated by the author..

It is worth noting that transactional leadership is effective in stable environments where routine tasks and clear guidelines are essential. It is a more reactive style, focusing on correcting deviations from established norms [18,19,39]. On the other hand, transformational leadership is well suited for dynamic and rapidly changing environments. It fosters innovation, adaptability, and a collective commitment to a shared vision. Transformational leaders are proactive, inspiring organizational change and creating an environment where followers feel empowered to contribute their best [18,40,41]. In essence, while transactional leadership ensures the efficiency of day-to-day operations, transformational leadership empowers organizations to thrive in the face of change and uncertainty. Effective leaders often employ a blend of both styles, adapting their approach to the demands of the situation and the characteristics of their followers [19,42].

Collectively, these approaches contribute to fostering healthier organizational cultures, improving employee engagement, and driving long-term success. However, critics argue that these models might face challenges in certain competitive environments, and the emphasis on personal characteristics can overshadow structural issues [13]. Nonetheless, the new leadership reflects a broader shift towards more inclusive, empathetic, and sustainable leadership practices [13,24]. In the 1990s, approaches such as authentic leadership, pioneered by scholars like Bill George, and servant leadership, articulated by Robert Greenleaf, posit that genuine leadership emanates from self-awareness, moral integrity, and staying true to core values. Leaders are encouraged to embrace their authentic selves, fostering transparency and trust [36,42]. Shared leadership is a departure from the traditional top-down hierarchy, embracing a more collaborative model [13]. This approach distributes leadership responsibilities across the organization, recognizing that leadership is a collective effort. Shared leadership fosters a culture of collaboration, where individuals at all levels contribute their unique skills and perspectives [43].

In addition, relational leadership places a premium on building meaningful and authentic relationships within the organization [13]. Leaders adopting this approach prioritize communication, trust building, and collaboration. The focus is on understanding and responding to the relational dynamics that shape organizational culture and effectiveness [13]. Ethical leadership, another facet of the new leadership, centers on the moral and principled aspects of leading. Leaders adhering to ethical leadership principles make decisions based on values, fairness, and integrity. This approach promotes a culture of ethical behavior and corporate responsibility.

Navigating Leadership Dynamics: Individual and Environment in the Digital Landscape

The 21st-century landscape is marked by the integration of various leadership styles, recognizing the need for flexibility and adaptability. The concept of adaptive leadership, proposed by Heifetz [24], underscores the importance of leaders adjusting their approaches based on the challenges and contexts they face [24]. A foundational principle of this approach is the concept of diagnostic work. Leaders engaging in adaptive leadership must meticulously diagnose problems, distinguishing between technical challenges with known solutions and adaptive challenges demanding innovative responses and new learning. Challenging the status quo is another hallmark of adaptive leadership. Leaders in this model disrupt existing norms, encouraging followers to confront uncomfortable truths and navigate the intricacies of change. The approach advocates for shared and distributed leadership, recognizing that leadership is not the sole responsibility of an individual but is distributed and shared across various levels of an organization or community.

Managing polarities is a key aspect of adaptive leadership, involving the delicate balance of competing values. Leaders guide individuals and organizations in navigating tensions without succumbing to either/or thinking. This holistic and integrative perspective aligns with the acknowledgment that adaptive challenges often require a nuanced understanding of conflicting values. Subsequent authors, such as Marty Linsky and Alexander Grashow, have expanded on Heifetz’s framework. They emphasize the emotional dimensions of adaptive challenges, the importance of resilience, and the ability to learn from failures as integral components of adaptive leadership. In practice, adaptive leadership finds application in diverse contexts, from organizational settings to community development and public policy. It encourages leaders to view challenges as opportunities for growth, fostering a culture of continuous learning and adaptability.

While widely embraced, adaptive leadership has not been without critiques. Some argue that its emphasis on challenging the status quo may encounter resistance, and the model’s lack of specific prescriptions for action could pose challenges for leaders navigating uncharted territory. In essence, adaptive leadership provides a dynamic and responsive approach to leadership in a world marked by rapid change and uncertainty. Its principles, rooted in Heifetz’s work and enriched by subsequent authors, offer a valuable framework for leaders seeking to navigate complexity and cultivate adaptive capacities within their organizations or communities [24]. Mary Uhl-Bien and her collaborators have significantly advanced our understanding of adaptive leadership, offering valuable perspectives to the field through their research and publications [8-10,13,16, 44].

For instance, Uhl-Bien, Marion, and McKelvey [44] introduce “complexity leadership theory”, an approach that tackles leadership in complex and dynamic organizational contexts. This theory aligns with Heifetz’s adaptive leadership, acknowledging the need for leaders to navigate complexity and engage in continuous adaptation [13,44]. Complexity leadership theory highlights the interplay of three dimensions in complex leadership: administrative leadership, adaptive leadership, and innovative leadership. These dimensions underscore the necessity for leaders to employ various forms of leadership based on the organizational context and challenges faced [13,44]. Moreover, it stresses the significance of an adaptive approach to leadership in complex environments, where technical solutions may prove insufficient. The capacity to learn, adapt, and manage complexity becomes paramount in such situations [13,45]. The symbiotic relationship between organizational structure and leadership styles becomes apparent when examining discussions in tandem. Burns and Stalker’s [3] mechanistic and organic structures align with task-oriented and relationship-oriented leadership styles, respectively. Transactional leadership may thrive in highly formalized and centralized structures, whereas transformational leadership, with its emphasis on inspiring change, may excel in dynamic and organic structures [3,18,19].

Furthermore, the contingency nature of both structure and leadership is evident. Lawrence and Lorsch’s contingency theory highlight that organizational structure effectiveness is contingent on external demands; mirroring Fiedler’s assertion, that leadership efficacy depends on situational favorability [5,34]. This discussion converges on organizational effectiveness. The alignment of leadership styles with organizational structures is imperative for optimal performance. A rigid, mechanistic structure may stifle the innovation advocated by transformational leadership, while a laissez-faire leadership style might struggle in a highly structured environment [19,46]. The dynamic interplay between organizational structure and leadership styles underscores the need for a nuanced and context-specific approach. Effective organizations exhibit congruence between their structures and leadership practices, recognizing the contingent nature of both elements in navigating the complexities of the business landscape [25].

Contemporary authors, such as Uhl-Bien and Arena [8-10], have offered insightful critiques regarding the predominant emphasis on entity-centric and charismatic perspectives in leadership literature. Uhl-Bien raises concerns about oversimplifying leadership dynamics and urges a more nuanced and dynamic understanding. One primary critique revolves around the entitycentric view, focusing on individual leaders as central figures within organizations. Uhl-Bien argues that this perspective oversimplifies leadership dynamics, overlooking the complex interplay of factors shaping organizational outcomes. Such a focus may not capture the distributed and relational nature of leadership in contemporary contexts. The charismatic leadership model, associated with transformative figures, also draws Uhl-Bien’s attention [13]. While acknowledging the motivational power of charismatic leaders, she underscores the potential risks of over-relying on charisma. This may contribute to romance and “heroic” narratives around leaders, overshadowing the collaborative and collective aspects of leadership crucial in modern organizations. Uhl-Bien advocates for a pluralistic and adaptive approach to leadership, recognizing diverse forms and sources of leadership. This perspective aligns with contemporary theories like complexity leadership theory [13,16], which she has contributed to developing.

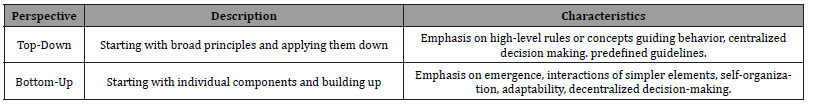

In essence, Uhl-Bien’s critiques prompt a reconsideration of leadership paradigms that overly prioritize individual leaders and charismatic qualities [13]. Embracing a more inclusive and distributed perspective captures the dynamic nature of leadership in today’s complex organizational landscapes. Several other scholars, including Ciulla [47], Kellerman [48], and Barker [49], echo critiques against entity-centric, top-down, and charismatic perspectives in leadership studies. They urge a more nuanced, ethical, and contextually aware approach that aligns with the intricate realities of contemporary organizational landscapes. In this process, contributions from scholars like Roger Penrose, known for his interdisciplinary work in physics and philosophy, add depth. His exploration of the nature of consciousness and the limit of artificial intelligence raises questions about true intelligence and consciousness achieved through algorithmic approaches. Penrose introduces the “top- down” and “bottom-up” perspectives, challenging conventional views on human cognition and computational models [50,51]. Table 11 summarizes the key characteristics of top-down and bottom-up organizing.

Table 11:Top-Down Vs. Bottom-Up.

Source:Elaborated by the author..

Penrose’s perspectives add depth to the discourse on designing intelligent systems, presenting the contrasting philosophies of the top-down and bottom-up approaches. While the top-down approach relies on predefined rules, the bottom-up approach emphasizes the emergence of intelligence through complex interactions. Penrose’s insights challenge conventional views on artificial intelligence, prompting reflections on the potential limitations of algorithmic approaches in capturing the richness of human cognition [50]. Simultaneously, authors from the school of object relations, such as Donald W. Winnicott, offer insightful perspectives applicable to modern leadership in horizontal, virtual, and distributed organizational structures. In today’s collaborative business landscape, characterized by networks and ecosystems, Winnicott’s emphasis on the “transitional space” is pertinent. This concept highlights the importance of an intermediary area between the internal and the external worlds, fostering creativity, innovation, and authentic self-expression [52].

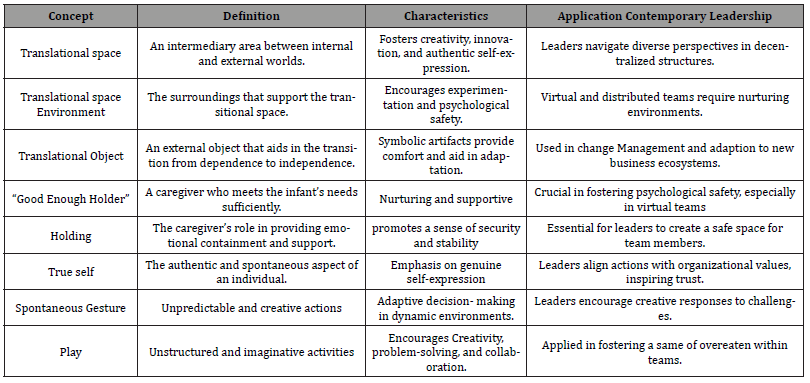

In a leadership context, the transitional space aligns with the need for leaders to navigate and bridge diverse perspectives within decentralized structures. Leaders must create environments that allow experimentation, where team members feel safe expressing their genuine selves while contributing collectively. The “good enough holder” concept, emphasizing a nurturing environment, is crucial for fostering psychological safety, especially in virtual and distributed teams. Additionally, Winnicott’s ideas on “spontaneous gesture” align with adaptive decision- making required in dynamic business ecosystems. Leaders, acting as holders, must be agile and responsive, encouraging spontaneous, creative responses to challenges. In horizontal, virtual, and shared spaces, Winnicott’s emphasis on authenticity and the “true self” becomes paramount. Leaders should ensure that their actions align with the values of the organization, thereby inspiring trust, and commitment, especially among a geographically dispersed workforce. Furthermore, Winnicott’s concept of “play” denotes spontaneous and creative activities, offering an authentic expression of the self and contributing to healthy emotional and relational development. This concept sheds light on various characteristics and potential applications in leadership contexts [51-53].

Table 12:Winnicott’s Main Concepts.

Source:Elaborated by the author

In exploring the application of Winnicott’s psychoanalytic concepts to contemporary leadership, Table 12 provides a comprehensive overview of his main ideas and their potential relevance in organizational settings. In summary, Winnicott’s psychoanalytic concepts provide a valuable lens for understanding the emotional dimensions of leadership in contemporary organizations. Incorporating these insights, leaders can cultivate more inclusive, innovative, and adaptive environments that align with the intricacies of today’s business landscape.

Hybridizing the Leadership’s Field Theory: Enabling Leadership as Holdership

In “Leadership for Organizational Adaptability: A Theoretical Synthesis and Integrative Framework”, Uhl-Bien and Arena [8- 10] discuss the concept of enabling leadership, emphasizing its relational dimension that transcends the dominance of leader personality found in entity-centric and charismatic approaches. This perspective underscores the hybrid nature of leadership’s field theory, highlighting the interplay between personality and the environment and emphasizing the dimension of “adaptive space” within enabling leadership. Concomitantly, Osborn, trace the evolution of leadership research, pointing to calls dating back to the 1970s to consider context as a crucial factor influencing leadership and its effectiveness. According to them, in the nested views of leadership, researchers typically initiate the analysis from the perspective of individual influence, particularly that of “role holders” such as managers. This approach is nested within the organizational context, closely aligning the analysis of leadership with the unit of analysis. The context is defined by organizational design, guiding the investigation into factors such as size, technology, and workflows within and between selected units. Conversely, pervasive views of leadership extend beyond formal positions and are embedded in context, allowing leadership to emerge informally and be distributed throughout a social system. Notable examples include the concept of the “romance of leadership”, where leadership is seen as a natural emergent phenomenon from social interaction. In these views, context spans from the micro-level (dyadic, relational contexts) to the macro-level (broader societal discourses), incorporating diverse factors such as shared concepts, individual interactions, and group dynamics.

In this context, they propose a hybrid perspective, suggesting the adaptive space as a kind of “transitional environment” of conflicting, connecting, and reintegration [8-10,52]. Based on this perspective, this article points out the integration of Penrose’s perspectives (Top-down and Bottom-up organizing) and Winnicott’s concepts related to “holdership”. This integration focuses on the role of the environment and person dimensions of leadership in constructing and sustaining transitional environments - or adaptive spaces - conducive to contemporary business models and organizational arrangements. This articulation can become particularly relevant in providing a more hybrid view between personality and the environment, offering a nuanced understanding of leadership dynamics in the digital landscape.

Conclusion

In the ever-evolving landscape of leadership theories and practices, a nuanced and adaptive approach becomes paramount. From classical models emphasizing task and relationship orientations to contemporary perspectives embracing complexity and distributed leadership, the journey through leadership literature reflects a continual quest for models that resonate with the intricate realities of organizational life [8-10,16,18,20,55,56].

The integration of various leadership styles, such as transactional, transformational, authentic, and adaptive, underscores the need for flexibility and adaptability in leadership. Leaders, who can skillfully navigate the complexities of stable and dynamic environments, blending transactional efficiency with transformational inspiration, are better equipped to foster healthier organizational cultures and drive long-term effectiveness [20,16,18,19,39].

The symbiotic relationship between organizational structure and leadership styles further emphasizes the importance of a context-specific approach. Mechanistic and organic structures align with transactional and transformational leadership, respectively, revealing the contingent nature of both elements. Effective organizations recognize the imperative of aligning their structures and leadership practices for optimal performance, acknowledging the dynamic interplay between the two [5,8-10,18,19,25,46]. Critiques from scholars like Uhl-Bien [13] prompt a reevaluation of predominant leadership paradigms. The shift from entitycentric and charismatic perspectives towards a more inclusive, distributed understanding of leadership aligns with contemporary theories such as complexity leadership theory. The emphasis on shared leadership and contextual awareness contributes to a comprehensive understanding of leadership, acknowledging its complex, evolving, and socially embedded nature [8-10,16].

In this rich tapestry of leadership scholarship, the interdisciplinary insights of figures like Penrose and Winnicott add depth to the discourse. Penrose’s exploration of consciousness challenges conventional views of artificial intelligence, prompting reflections on the nature of intelligence and the limitations of algorithmic approaches [51]. Winnicott’s psychoanalytic concepts offer a unique lens to understand the emotional dimensions of leadership, particularly in decentralized and virtual organizational structures [51-53]. As one navigates the complexities of leadership in the 21st century, embracing diversity, fostering innovation, and nurturing authentic relationships emerge as key imperatives. Leaders who integrate these insights into their practices contribute to the creation of horizontal, adaptive, inclusive, and emotionally intelligent organizational environments, poised to thrive amid the uncertainties of the contemporary business landscape [8- 10,13,50,52,57-60].

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lewin K (1935) A Dynamic Theory of Personality. New York: Mc Graw-

- Barnard CI (1938) The Functions of the Executive. Harvard University Press.

- Burns T, Stalker GM (1961) The Management of Innovation. Tavistock Publications.

- Woodward J (1965) Industrial Organization: Theory and Oxford University Press.

- Lawrence PR, Lorsch JW (1967) Differentiation and integration in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 12(1): 1-47.

- Schein EH (1985) Organizational Culture and Leadership. Jossey-Bass.

- Heckscher C, Adler PS (2017) The Firm as a Collaborative Community: Reconstructing Trust in the Knowledge Economy. Oxford University Press.

- Uhl-Bien M, Arena M (2018) Leadership for Complexity: Clarifying the Craft of Complexity Leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(2): 101-301.

- Uhl-Bien M, Arena M (2018) Complexity Leadership: Enabling People and Organizations for Adaptability. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management.

- Uhl-Bien M, Arena MJ, Ospina SM (2018) Advancing relational leadership research: A dialogue starter. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(1): 1-6.

- Sundararajan A (2016) The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism. MIT Press.

- Kelly J (1994) Rethinking Industrial Relations: Mobilization, Collectivism and Long Routledge.

- Uhl-Bien M (2006) Relational Leadership Theory: Exploring the Social Processes of Leadership and Organizing. The Leadership Quarterly 17(6): 654-676.

- Mintzberg H (1983) Structure in Fives: Designing Effective Organizations. Prentice-Hall.

- Morgan G (1986) Images of Sage Publications.

- Uhl-Bien M, Marion R, McKelvey B (2007) Complexity Leadership Theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge The Leadership Quarterly 18(4): 298-318.

- Stacey RD (2003) Strategic Management and Organizational Dynamics: The Challenge of Complexity. Pearson Education.

- Burns JM (1978) Harper & Row.

- Bass BM (1985) Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. Free Press.

- Northouse PG (2018) Leadership: Theory and Sage Publications.

- Goleman D (1995) Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than Bantam Books.

- Blanchard K, Hersey P (1977) Situational Leadership: An Integrative Springer.

- Weick KE (1995) Sensemaking in Sage Publications.

- Heifetz RA (1994) Leadership Without Easy Harvard University Press.

- Daft RL (2016) Organization Theory and Design. Cengage

- Perrow C (1986) Complex Organizations: A Critical Mc Graw-Hill.

- Mintzberg H (1989) Mintzberg on Management: Inside our Strange World of New York, NY: Free Press.

- Carlyle T (1840) On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History. London, UK: James

- Cartwright D, Zander A (1953) Group dynamics: Research and theory. Row, Peterson.

- Stogdill RM (1948) Personal Factors Associated with Leadership: A Survey of the Literature. Journal of Psychology 25(1): 35-71.

- Lewin, K (1943) Defining the “Field at a Given Time”. Psychological Review 50(3): 292-

- Lewin K, Lippitt R, White RK (1939) Patterns of aggressive behavior in experimentally created social climates. Journal of Social Psychology 10(2): 271-299.

- Blake RR, Mouton JS (1964) The Managerial Grid: The Key to Leadership Houston TX: Gulf Publishing Company.

- Fiedler FE (1967) A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York, NY: Mc Graw-Hill.

- Blanchard KH, Zigarmi, P, Zigarmi D (1985) Leadership and the One Minute Harvard Business Review Press.

- Greenleaf RK (1977) Servant Leadership: A Journey into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness. Paulist Press.

- Hersey P, Blanchard KH (1969) Management of Organizational Behavior: Utilizing Human Resources. Prentice Hall.

- Burns JM (2003) Transforming Grove Press.

- Avolio BJ, Bass BM (2004) Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire: Manual and sampler set. Mind Garden.

- Bass BM, Riggio RE (2006) Transformational Psychology Press.

- Avolio BJ, Bass BM (1991) The Full Range of Leadership Development: Basic and Advanced Manuals. Binghamton, NY: Bass, Avolio & Associates.

- George B (2003) Authentic Leadership: Rediscovering the Secrets to Creating Lasting Jossey-Bass.

- Barker RA, Barber AE (2012) Telling the Whole Story: Resilience, Sensemaking, and the Work of Integrating Life Experience. Human Relations 65(5): 575-601.

- Uhl-Bien M, Ospina S (2012) Advancing Relational Leadership Research: A Dialogue Among Perspectives. IAP.

- Uhl-Bien M, Marion R (2009) Complexity Leadership in Bureaucratic Forms of Organizing: A Meso Model. The Leadership Quarterly 20(4): 631-650.

- Mintzberg H (1979) The structuring of Prentice-Hall.

- Ciulla JB (1998) Leadership Ethics: Mapping the Business Ethics Quarterly 8(3): 415-435.

- Kellerman B (1984) Leadership: Multidisciplinary Prentice-Hall.

- Barker JR (1997) Tightening the Iron Cage: Concretive Control in Self-Managing Administrative Science Quarterly 42(2): 408-437.

- Penrose R (1994) Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Oxford University Press.

- Penrose R (1989) The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and the Laws of Physics. Oxford University Press.

- Winnicott DW (1971) Playing and Routledge.

- Winnicott DW (1965) The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating International Universities Press.

- Winnicott DW (1958) Collected Papers: Through Pediatrics to Psycho-Analysis. Tavistock

- Yukl G (2012) Leadership in organizations. Pearson.

- Barker RA, Barker A (1993) The social psychology of Springer.

- Nonaka I, Takeuchi H (1986) The New Product Development Harvard Business Review 64(1): 137-146.

- Avolio BJ, Gardner WL, Walumbwa FO (2009) Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology 60: 421-449.

- Lichtenstein BB, Uhl-Bien M, Marion R, Seers A, Orton JD, and et.al (2006) Complexity Leadership Theory: An Interactive Perspective on Leading in Complex Adaptive Systems.

- Winnicott DW (1953) Transitional Objects and Transitional Phenomena: A Study of the First Not-Me Possession. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis 34(2):89-97.

-

Anderson Santanna. Exploring the Interplay: Organizational Types and Leadership Styles in Contemporary Dynamics. Iris J of Eco & Buss Manag. 2(1): 2024. IJEBM.MS.ID.000527.

-

Truck driver detention, Driving hours, Business, Trickle-down effect, Speed, Breaks, Load type

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.