Research Article

Research Article

An overview of the economic strategy of a small island developing state (SIDS): the case study of São Tomé and Príncipe (Africa)

Eduardo Moraes Sarmento* and Zorro Mendes

Department of Economics, Lisbon School of Economics and Management (ISEG), University of Lisbon and CEsA/CSG/ISEG/ULisboa, Portugal

Eduardo Moraes Sarmento, Lisbon School of Economics and Management (ISEG), University of Lisbon, Portugal.

Received Date:July 09, 2024; Published Date: July 15, 2024

Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of this research is to investigate the challenges and strengths of São Tomé and Príncipe (STP), considered a traditional

small island developing state (SIDS), a group of developing countries that face several typical vulnerabilities. As in other SIDS, tourism has been

considered an optional development activity to overcome some of these constraints. However, to succeed it is necessary to reflect on its strengths

and limitations. This paper aims to understand the major drivers, and barriers of a tourism policy which can be implemented in STP by the national

government as well as regional or international organizations and stakeholders to guide their actions towards this regard.

Design/Methodology/Approach: This research is based on a case study methodology based on secondary data.

Findings: This paper shows the importance of the country substantial relationships between economic performance and favorable social and

environmental indices, highlighting the interconnectivity of the two. Furthermore, a significant association was discovered between economic,

social, and environmental issues where tourism may be an effective alternative to diversify the economic activity and above all reflect its potential

on local communities and local entrepreneurs.

Originality/Value: This study adds new managerial and especially economic discussion and perspectives by objectively illustrating the

interdependence of economic, social, and environmental factors in tourism development programmers. The study alerts for the importance to

overcome some traditional SIDS limitations and vulnerabilities in order to achieve a new economic, social and environmental prosper path. Tourism,

may be an opportunity, but only if the country succeeds in reducing social problems, economic imbalances and environmental issues.

Keywords: São Tomé and Príncipe; islands; tourism strategy; small island developing state (SIDS)

Introduction

Traditionally, we have found 58 small island developing states (SIDS) as a unique group of developing countries located in the Atlantic, Indian Ocean, Mediterranean and South China Sea (AIMS), Caribbean and Pacific regions. SIDS face a myriad of challenges and impacts that may limit their social, economic and environmental paths as well as perpetuate their exposure and sensitivity to shocks, and the costly nature of adaptation [1].

Historically, the difficulty to implement national programs along with the failure of governments to implement policies and measures to overcome the country’s vulnerabilities has raised various questions, including the extent to which mainstreaming is realistic and whether it is the only way forward [1].

This paper aims to answer two questions: (i) what are the drivers of STP’s economic option, and (ii) what is the importance and potential of tourism in this SIDS? Methodologically we have opted for a qualitative approach mainly based on secondary data. This paper is important for three main reasons. First, it focuses exclusively on a SIDS like São Tomé and Príncipe and therefore it contributes to diminish a major gap in the literature especially because SIDS only have gained a special attention since the adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992 but also due to their unique and overlapping vulnerabilities that have been discussed in the literature [2, 3]. Second, this paper helps to systematize and identify the drivers and barriers of one small island. Third, the existing mainstreaming literature has largely concluded on its below-par success. So, this study aims to bring new insights and recommendations to possible improvements that national governments and regional organizations can implement in the country.

Literature Review

Environmental issues, specifically climate, environmental degradation and the loss of biodiversity change poses a systemic threat to economic prosperity, social welfare, and environmental health across the globe and specifically on SIDS countries due to their geographic location and coastal development patterns making them extremely vulnerable to a range of climate shocks (e.g., high‐intensity hurricanes, sea‐level rise). Nowadays, various climate‐related disasters have triggered tens of billions of dollars in property losses, thousands of lives lost, and corresponding absolute declines in gross domestic product (GDP) in these regions [4], worsening the living conditions of citizens [5].

Many SIDS share common elements like remote geographies and high coastline‐to‐land ratio areas, with much of the population and critical infrastructure systems located close to the coast. In other words, SIDS populations and physical infrastructure such as roads, air and seaports, diverse utilities, and telecommunications are exposed to long‐term environmental stressors [6].

Global shipping plays an important role in international trade and in many SIDS due to fact they are islands and in many cases archipelagos. But, shipping activities, generate negative environmental impacts on port and coastal ecosystems because they may introduce alien species via ballast water discharge and biofouling [7]. These nonindigenous species may cause serious problems to human health, ecosystems, and the whole economy [8] and therefore it is crucial these countries can provide efficient water treatment methods that can be used in ballast water treatment, and may control the invasive species as proposed by Saleh [9, 10].

Although the impact of ballast water regulation on Small Island Developing States (SIDS) has not been improved efficiently, these countries have a unique social, economic, and environmental conditions making them extremely vulnerable to external shocks. Most SIDS rely heavily on the world market, to export oil, ores, phosphates, and other raw materials, which are important components of their national economies. But they are also disproportionately dependent on inter-island shipping for the delivery of necessary food, energy, and/or equipment imports. So, in many SIDS, shipping connectivity and efficiency may be seriously affected by cost changes and they may ultimately disrupt trade under conditions where they do not operate or have ownership control of ocean transport fleets serving their economies [7].

But, even tourism activity, a common economic diversification and specialization in many islands and low-income countries, may be a problem since due to the lack of functional infrastructures and services, these countries may not be ready to the extra inflow of more and unexpected waste types generated by tourists that otherwise would not occur [11].

These problems highlight the importance of an active participation and involvement of local partners and stakeholders supported by international experts and government, to suggest how touristic centres can serve as core of circular approaches or the implementation of a ‘green tourism marketing’ [12].

Developing countries often have a higher propensity for debt distress than developed ones and small economies are even more vulnerable to external shocks than larger ones. A country facing an elevated debt can potentially face detrimental effects on economic growth, especially if it exceeds a country-specific threshold and this situation may be aggravated with the heightened uncertainty of the macroeconomic environment [13]. As a consequence, governments will have to deal with higher interest payments as well as accessing concessional financing tranche with stringent conditions and therefore policymakers will have to deal with a permanent debt sustainability and management of the public debt [14] that in many cases will have repercussions into future time periods limiting their capacity to access to future financing and investment [15]. Many developing countries face borrowing costs three times higher than their developed counterparts [13].

In summary, we can see conclude their although there are various definitions of SIDS, we may find some specific features, generally associated with the traditional small geographic size of its territory, demographic smallness or constraints, or even a composite of different approaches relying on different variables ranging from their traditional economic openness, distance from the main international economic markets, dependence on a few products to export, political stabilities, and social cohesion [16].

Methodology

The current paper is based on a qualitative approach based on a case study methodology. Although based on secondary data, this perspective allows the researcher to be in the position of an observer [17]. The design of this case study is descriptive in its essence as proposed by Tin, aligned with the research question(s), and based on a systematic data collection and management [18,19].

Data collection was collected from two main alternative methods: (i) documentation of both international institutions provided by the World Bank, World Travel and Tourism Council, STP Government’s statistics and documents among others, and (ii) archival records. This process has the advantage of allowing to collect rich data that accurately represents the phenomena under investigation [20].

São Tomé and Principe: an overview

São Tomé e Príncipe is a traditional Small Island Developing Country (SIDS) located in the Gulf of Guinea. It comprises two islands and several mostly uninhabited islets covering 1,000 km2, with a total population of 223,561 inhabitants in 2024 (111,553 male and 112,008 female).

Like many other small islands, these countries face some common characteristics: (i) being bordered or bounded with clearly demarcated land-based spatial limits; (ii) being small in terms of land area, population, resources, and livelihood opportunities; (iii) distance, marginalization, isolation, or separation from other land areas, peoples, and communities; and (iv) literality as a consequence of land–water interactions, coastal zones, and intersections of archipelagos. It brings additional opportunities using resources for fishing, tourism, and trade [2, 16].

STP has been considered a lower-middle-income country, with a gross national income that has been growing steadily in the last years: USD 766.853 mn in 2020; USD 781.928 mn in 2022 and USD 801.321 mn in 2023 [21].

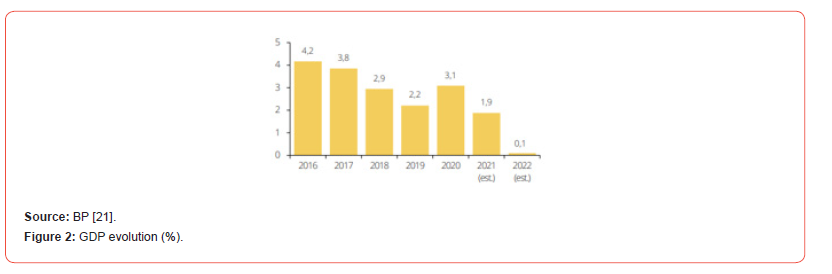

As seen in Figure 2, GDP’s evolution was only 0,1% in 2022, one of the lowest values in the last 15 years. However, it is expected to be 2% in 2023. This situation is a problem partially explained by the negative’s contribution of agriculture and fisheries that were both affected by the growth of production costs. This situation is also complemented by the stagnation of investment and the raise of imports that represented 45% of the GDP in 2022 demonstrating a huge dependence and exposure of this economy to international prices [21].

According to UNDP’s Report, São Tomé and Príncipe’s Human Development Index (HDI) value is 0.613 (2022) placing the country in the medium human development category - ranking it 141 out of 193 countries and territories and above the sub- Saharan Africa average. Between 1990 and 2022, São Tomé and Príncipe’s HDI value increased from 0.480 to 0.613, an increase of 27.7 percent. During this period, São Tomé and Príncipe’s life expectancy at birth increased by 7.3 years, the average number of years of schooling increased by 4.5 years and the number of years of schooling increased by 1.8 years. São Tomé and Príncipe’s per capita income increased by 71.0 percent between 1990 and 2022 [22]. This situation reflects the considerable progress in reducing child mortality and malnutrition and the improvement of maternal health achieved in the last decades [23].

Nevertheless, the country has been facing serious challenges in eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, with little progress made since 2000. In 2012, almost two thirds of the population lived below the poverty line, with women being at greater risk of poverty than men. The most recent survey data refers to 2019 and shows that 11.7 percent of the population (26 thousand people in 2021) is multidimensionally poor while an additional 17.0 percent classified as vulnerable to multidimensional poverty (38 thousand people in 2021). The intensity of deprivations, which is the average deprivation score among people living in multidimensional poverty, is 40.9 percent. The headcount or incidence of multidimensional poverty is 3.9 percentage points lower than the incidence of monetary poverty which implies that individuals living below the monetary poverty line may have access to non-income resources [23].

Almost 50 per cent of people active in the labour market are employed in the informal sector, earning below decent wages. The unemployment rate in the country is approximately 14.4 per cent in 2022 (20.0 per cent for women, 10,1 per cent for men and 23 per cent for young people) [21, 23]. The country faced difficulties in attracting external financing, which together with the late approval of the state budget (June 2023) affected public investment capacity as well as economic activity in the first half of 2023. In June, STP suffered a fuel supply crisis. As a way of rationalizing diesel reserves and also due to the shortage of foreign currency, the country was forced to extend the energy cuts that had already been in place. On the other hand, there was a slowdown in global international demand, which affected not only the desirable growth in tourism but also the rise in prices of imported foodstuffs [21].

The socioeconomic development of the country has been sustained by external assistance, government borrowing (97% of the public investment budget is financed through debt and external aid) and foreign direct investment, mainly in the tourism and related services sector [23].

STP, as explained in earlier section, is like many SIDS already experiencing the impact of climate change mainly due to drought which accounts for almost 25 percent of the annual occurrence of hazards. Water scarcity has been a problem in the north of the main island creating huge problems to agriculture development since they don´t have a proper irrigation system. The country is also vulnerable to coastal and river flash floods following heavy rainfall. Sea-level rise has been continuous since 1993, with tides affecting the coastline [23].

As many SIDS, tourism may be an important activity to diversify the economy. In fact, after the COVID-19 pandemic, the tourism contribution to GDP has been evolving positively. In 2019 it represented 14.2% (USD 72.9 mn), in 2023 it represented 12.7% (USD 71.8 mn), and it is forecast to rise by 4.5% pa to USD 111.7 mn from 2023 to 2033 (15.5% of GDP).

But we also have to look at tourism’s contribution to employment. Total tourism jobs in 2019 represented 8.5 (000s) - 14.6%, and in 2023, 8.4 (000s) - 13.5%. By 2033, tourism is expected to account for 14,003 jobs (17.5% of total employment), which represents an increase of 5.2% pa since 2023.

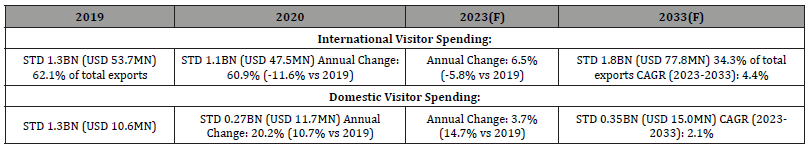

Another key component to the country’s economic performance is the country’s visitor spending. In STP, there has been a growing importance of these receipts for local economy since the international expenditure is expected to evolve from USD 53.7 mn in 2019 (62.1% of total exports) to around USD 77.8 mn in 2033 representing 34.3% of the total exports.

Table 1:São Tomé and Príncipe visitor spending.

Source: WTTC (2024).

According to the National Plan, it is projected to achieve a tourist inflow of more than 50,000 tourists/year by 2025, an increase in the number of rooms from the current 723 to 980 and a growth of 73.4% in the sector’s contribution to the GDP in the same period [23].

Discussion/Conclusion

As described in the previous section, STP is a country that has been facing some historical structural challenges and imbalances common of its SIDS condition mainly due to its small dimension and remoteness. Therefore, under this situation, the recent World Bank Systematic Country Diagnostic identified tourism, together with agriculture and fisheries, as sectors with some potential to reshape the economic growth along with job creation and thus leveraging STP’s natural capital.

But this goal must be part of a major strategy. Government must be aware of the significative importance to deal with STP’s high vulnerability to shocks, including climate change, potential uncontrolled development, water pollution, etc., that if ignored or minimized may threaten the natural assets that underpin future growth prospects.

As occurred in other countries, tourism was growing strongly before the COVID-19 pandemic, with an average annual growth rate of 15% between 2015 and 2019, when it reached almost 35,000 tourist arrivals. By 2020, the number of tourists decreased by 70% and revenues generated by the sector fell by 66%. By the middle of that year, 68% of enterprises in the sector were temporarily closed. The tourism inflow started to recover in 2021 (15,700 tourists, a growth of 45% over 2020) and the recovery is picking up pace in 2022 (over 14,000 tourists in January-July).

It is important to notice that STP’s three main tourism markets in 2022 were Angola (39%), Portugal (6%), and France (2%). The main tourism products offered by the country are Sun and Beach tourism and ecotourism (land and marine). STP faces a huge challenge of impacting this tourism activity in local economy through its various potential impacts on GDP, job creation, poverty reduction, raise export revenues as well as high-value exports of goods such as cocoa products, coffee, pepper and natural cosmetics, which are all already bought by tourists as local souvenirs, territorial reorganization, and economic and social diversification. Other destination such as Canaries, Cape Verde, Madeira and Azores show the importance of a nature-based tourism strategy since for example, a well-preserved coral reefs and seagrass beds, not only contribute to avoid further erosion rates, but also create white sand and nurture biodiversity, which is one important attraction for SIDS’ visitors [23].

However, the country still faces various other specific challenges constrains that if not properly managed may affect the implementation of a long-term sustainable tourism development. We can emphasize several challenges including infrastructure bottlenecks (mainly in the energy sector with long and almost daily energy cuts) and limited connectivity (which has gone worse after the Covid-19 pandemics), a difficult business environment that not only discourages private investment but also doesn’t create the capacity to attract anchor investments, and even weaknesses in governance and institutional capacity that are essential for policy coordination and implementation. But at a national level, we also find sector-specific challenges due to constraints in the technical capacity and resources of the Tourism Authority (the General Directorate of Tourism and Hospitality - DTGH, linked to the Ministry of Tourism and Culture), insufficient coordination to develop and implement tourism policies, and finally a limited consultation and engagement with tourism operators and sector stakeholders.

This situation is aggravated by the lack of development of the tourism offer namely because of the insufficient number of accommodations, food deficiencies, the absence of qualified tours and other leisure activities for tourists. In STP, the small and medium enterprises and their managers face severe challenges in accessing finance and skills which may constraint the development of the tourism value chain, and the opportunity for creating necessary linkages with other national sectors mainly fisheries and agriculture.

However, on the positive side, we have seen recently some important developments namely the expansion in the use of international credit cards and ATMs, better organization of private sector operators and associations, and the involvement of nongovernmental organizations in various initiatives to support a sustainable tourism strategy.

As in other SIDS experiences and also in STP, there is no doubt that if this activity is properly managed it may be seen as an opportunity to put STP’s tourism sector on a renewed pathway of sustainable and inclusive growth because of its potential to boost resilience and circularity, protecting fragile ecosystems and biodiversity, promoting the blue economy as well as the circular economy, and naturally contributing to a greater involvement of local communities, thus improving the tourism performance and benefiting the whole society.

The country strategic plan (CSP) for STP for 2024–2028 is based on the achievements of the previous CSP for 2019–2024 who defined several priorities based on two pillars: (i) Pillar 1 (accelerated and sustainable growth) had four axes: diversification of the economy and expansion of its productive base; improved strategic management of development and management of public finances; modernization of the economic and social infrastructure; and improved land management and environmental preservation, (ii) Pillar 2 aimed to improve social cohesion and external credibility by strengthening human capital and governance; promoting young people, strengthening the family and protecting vulnerable groups; fostering appreciation of the national culture, supporting development and including the diaspora; strengthening local development centers and promoting decentralization; and consolidating international cooperation and preserving national sovereignty [23].

The success of these priorities, which are aligned with other international Institutions (United Nations, World Bank, etc.) are fundamental for São Tomé and Príncipe’s future internal well-being and to (re)shape its capacity to attract more external investors as well as develop a consistent tourism strategy that may decisively push the country into another level of development.

Declarations

Funding

The authors states that they did not receive any funds for this project.

Competing Interests

The authors declares that they have no competing interest

Data Availability Statement

All the data used by authors was collected from international reports. Author worked on implementing the same using real world data with appropriate permissions.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare they doesn´t have any conflict of interest.

References

- Robinson Stacy-Ann (2019) Mainstreaming climate change adaptation in small island developing states. Climate and Development 11(1): 47-59.

- Baldacchino G (2018) The Routledge International Handbook of Island Studies. Routledge: Abingdon, UK.

- Robinson Stacy-Ann (2017) Climate change adaptation trends in small island developing states. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 22(4): 669-691.

- Galindo Paliza M, Hoffman B, Vogt‐Schilb A (2022) How much will it cost to achieve the climate goals in Latin America and the Caribbean. Inter‐American Development Bank.

- Ajanaku B, Collins A (2021) Economic growth and deforestation in African countries: Is the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis applicable. Forest Policy and Economics 129: 102488.

- Galaitsi S, Corbin C, Cox Shelly‐Ann, Joseph G, McConney P, et al. (2023) Balancing climate resilience and adaptation for Caribbean Small Island Developing States (SIDS): Building institutional capacity. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 1-19.

- Wang Z, Countryman A, Corbett J, Saebi M (2022) Economic and environmental impacts of ballast water management on Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries. Journal of Environmental Management 301: 113779.

- Shackleton T, Larson H, Novoa A, Richardson D, Kull C (2019) The human and social dimensions of invasion science and management. Journal of Environmental Management 229: 1-9.

- Saleh T (2021) Protocols for Synthesis of Nanomaterials, Polymers, and Green Materials as Adsorbents for Water Treatment Technologies. Environmental Technology & Innovation pp. 101821.

- Saleh T (2020) Nanomaterials: classification, properties, and environmental toxicities. Environmental Technology & Innovation 20: 101067.

- Tsai F, Bui T, Tseng M, Lim M, Tan R (2021) Sustainable solid-waste management in coastal and marine tourism cities in Vietnam: A hierarchical-level approach. Resources Conservation and Recycling 168: 105266.

- Ferronato N, Mertenat A, Zurbrugg C, Torreta V (2024) Can tourism support resource circularity in small islands? On-field analysis and intervention proposals in Madagascar. Waste Management & Research 42(5): 406-417.

- Rahaman A, Mahadeo S (2024) Fiscal Reaction Functions Augmented with Bespoke Debt Indicators: Evidence from Small Island States. The Journal of Development Studies 1-17.

- Bouabdallah O, Checherita-Westphal C, Warmedinger T, De Stefani R, Drudi F, et al. (2017) Debt sustainability analysis for euro area sovereigns: A methodological framework (ECB Occasional Paper Series No. 184). Frankfurt: European Central Bank.

- Turan T, Yanikkaya H (2021) External debt, growth and investment for developing countries: some evidence for the debt overhang hypothesis. Portuguese Economic Journal 20(3): 319-341.

- Sarmento E, da Silva A (2024) Cape Verde: Islands of Vulnerability or Resilience. A Transition from a MIRAB Model into a TOURAB One Tourism and Hospitality 5: 80-94.

- Vieira C (2023) Case study as a qualitative research methodology. Performance Improvement 62(4): 125-130.

- Russell C, Gregory D, Ploeg J, DiCenso A, Guyatt G (2005) Qualitative research. In A DiCenso, G Guyatt, D Ciliska (Eds.), Evidence-based nursing: A guide to clinical practice pp. 120-135.

- Blackman A (2010) Coaching as a leadership development tool for teachers. Professional Development in Education 36(3): 421-441.

- Hughes J, McDonagh J (2017) In defense of the case study methodology for research into strategy practice. Irish Journal of Management 36(2): 129-145.

- Bank of Portugal BP (2024) Evolution of the economies of PALOP’s and East Timor. Lisbon: Bank of Portugal.

- United Nations Developing Programme UNDP (2024) Ending the deadlock: reimagining cooperation in a polarized world. USA: UNDP.

- World Food Programme WFP (2019) São Tomé and Príncipe country strategic plan (2019–2024). USA: WFP.

-

Eduardo Moraes Sarmento* and Zorro Mendes. An overview of the economic strategy of a small island developing state (SIDS): the case study of São Tomé and Príncipe (Africa). Iris J of Eco & Buss Manag. 2(3): 2024. IJEBM.MS.ID.000540.

-

Vulnerabilities, Economic imbalances, Gross domestic product, High‐intensity hurricanes, Sea‐level rise, Green tourism marketing, Macroeconomic environment, External financing, Territorial reorganization

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.