Review Article

Review Article

From Hybrid Integration to Monolithic Integration: The Ge/GOI SWIR Pathway for Future Space Systems

Yuanhao Miao*, and Henry H Radamson*

Research and Development Center of Optoelectronic Hybrid IC, Guangdong Greater Bay Area Institute of Integrated Circuit and System, Guangzhou, China

Yuanhao Miao, Research and Development Center of

Optoelectronic Hybrid IC, Guangdong Greater Bay Area Institute of Integrated

Circuit and System, Guangzhou, China

Henry H. Radamson, Research and Development Center of Optoelectronic Hybrid IC,

Guangdong Greater Bay Area Institute of Integrated Circuit and System, Guangzhou,

China

Received Date:December 10, 2025; Published Date: December 17, 2025

Abstract

The short-wave infrared (SWIR) spectrum has crystallized as a critical impetus for two defining endeavors of modern space science: probing the faintest cosmological signals and establishing high-capacity connectivity in orbit. This convergence is governed by a shared, stringent set of physical and engineering to deal with constraints-extracting vanishingly faint signals against noise, enabling orders-of-magnitude leaps in data throughput, and deploying robust hardware in suitable scales. This review examines a pivotal technological vector addressing the above constraints: the strategic evolution from hybridized photodetector assemblies to monolithically integrated Si-based platforms. We present Germanium and Germanium-on- Insulator (GOI) photodetectors exemplify this shift, offering dual integration pathways. While hybrid integration via flip-chip bonding currently supports high-performance systems, the ultimate monolithic integration path stands as a systemic enabler. By co-integrating high-performance SWIR detection with Si readout and processing electronics, a monolithic approach circumvents fundamental bottlenecks in complexity, scalability, and functional density. This capability paves the path for a paradigm in mission architecture, facilitating systems designed to concurrently execute deep scientific observation and high-rate data transport, thereby redefining the principles of future spaceborne system design.

Keywords: Short-wave infrared (SWIR); germanium-on-Insulator (GOI); monolithic integration; hybrid integration; space systems

SWIR Imperative: A solution of Scientific and Operational Demands

The strategic primacy of the short-wave infrared band (1.5- 3.0 μm) is rooted in its unique capacity to address first-order limitations in two distinct yet increasingly interdependent domains. For frontier astrophysics, SWIR observation is indispensable. It serves as the primary window for cosmic dawn studies, capturing redshifted emission from the first stars and galaxies. It is equally critical for exoplanetary atmospheric spectroscopy, hosting the definitive molecular fingerprints (H2O, CH4, CO2) for assessing habitability. Moreover, its ability to penetrate interstellar dust enables an excellent census of stellar and planetary formation. To accomplish the above tasks solid specifications for the detector are required: ultralow dark currents (in general achievable only with deep cryogenics), near-perfect quantum efficiency, and superlative uniformity across large-area focal planes-requirements that persistently test the limits of semiconductor material science [1,2].

In parallel, the architecture of space-based telecommunications is undergoing a fundamental transition from RF to optical links, with the SWIR band-particularly the mature 1.55 μm windowas its cornerstone. The imperative is the bandwidth-distance product; optical carriers support multi-gigabit to terabit-class data rates, a prerequisite for the viability of mega-constellations and interplanetary internetworks. This imposes a complementary set of detector requirements: multi-gigahertz bandwidth for high-speed communication, exceptional linearity over wide dynamic ranges to manage link margin variance, and inherent resilience to the space radiation environment. The emergence of these astrophysical and telecommunications drivers generates a powerful, unified demand for technological evolution: systems that deliver exponentially greater performance per unit of mass, power, and volume (SWaP), while being amenable to high-yield, scalable manufacturing [3,4].

The GOI Platform: A Strategic Pivot with Dual Integration Pathways

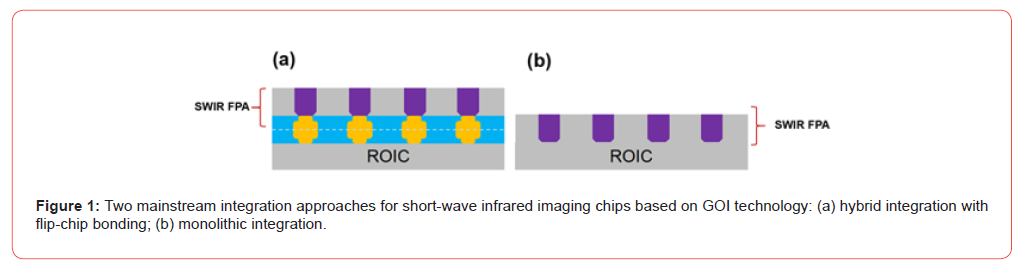

The collective pressure from these dual drivers is precipitating a strategic evolution in photodetector technology. GOI has advanced from a materials science prospect to a credible systemslevel platform, offering two distinct integration pathways to meet varying mission requirements: the established hybrid integration and the frontier monolithic integration (Figure 1).

Incumbent Workhorse: Hybrid Integration via Flip-Chip Bonding

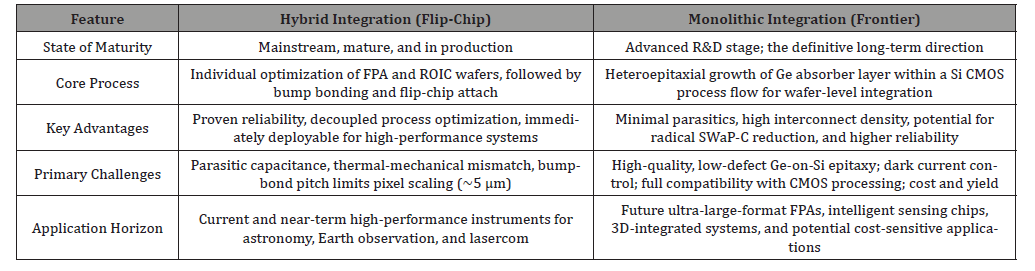

Presently, the dominant and most technologically mature method for fabricating high-performance Ge and GOI-based SWIR focal plane arrays (FPAs) is hybrid integration. This approach typically employs flip-chip bonding, where independently fabricated detector arrays and Si readout integrated circuits (ROICs) are interconnected via a matrix of micro-bumps (e.g., indium). This methodology decouples the optimization of the photodetector material growth, contact formation and the complex CMOS ROIC fabrication, allowing each to be processed in their ideal conditions [5,6]. Consequently, hybrid integration delivers reliable, high-performance imagers and is the backbone of current state-ofthe- art systems for both astronomical instrumentation and satellite sensing. Its primary limitations are intrinsic to the architecture: parasitic capacitance from bump bonds, thermal expansion mismatch between materials, and practical limits on interconnect pitch that challenge pixel miniaturization (Table 1).

Table 1:Comparison of Integration Pathways for Ge/GOI SWIR FPA.

Foundational Frontier: Monolithic Integration as a Systemic Enabler

In contrast, monolithic integration represents the definitive architectural goal and a paradigm shift. This path involves the direct heteroepitaxial growth of high-quality Ge (or Ge/SiGe heterostructures) on the Si ROIC wafer within a modified CMOS process flow. This approach dissolves the traditional FPA-ROIC interface, eliminating the need for bump bonds and their associated drawbacks. The GOI substrate is a critical enabler for this path. The buried oxide layer provides essential electrical isolation to suppress substrate leakage, enables the creation of thin, fully depleted absorber regions for low capacitance and high speed, and acts as an efficient back reflector for enhanced light absorption [7-11]. This engineered environment is ideal for advanced device concepts, including those employing bandgap engineering via quantum wells for spectral tailoring (Table 1). The Ge/GOI technology has been developed for SWIR technology and it has been successfully tested for SWIR imaging.

Navigating the Developmental Trajectory

A rigorous assessment necessitates acknowledging this dualpath reality. While monolithic integration holds the promise of systemic transformation, its full maturation requires significant advances in process technology. Key challenges include achieving high-quality, low-defect-density Ge epitaxy on large-area Si wafers, developing passivation schemes to suppress surface-related dark current in monolithic junctions, and ensuring the entire process flow is compatible with high-yield CMOS fabrication and space-level radiation hardness [12-14]. Therefore, the current technological landscape is characterized by a parallel development strategy: continuous refinement of hybrid integration supports demanding near- and mid-term missions, while sustained investment in foundational materials and process science is essential to unlock the long-term, disruptive potential of monolithic systems-on-achip.

Enabling a Paradigm of Multifunctional and Distributed Space Systems

The profound implication of this technological evolution, particularly as monolithic integration matures, transcends component-level improvement, heralding the feasibility of a new class of multifunctional, intelligently integrated space missions. This integration enables the conception of dual-use electro-optical cores. A future monolithic GOI-based system-on-chip could partition its pixel matrix into regions optimized for high-dynamic-range, lowframe- rate scientific imaging and others designed as waveguidecoupled, high-speed photodiodes for optical communication. Governed by a unified digital control and processing backend, such a payload could perform astronomical surveys or Earth observation while simultaneously operating as a reconfigurable node in a laser communication network, all through a shared aperture. This represents a decisive move away from federated, single-purpose instrument clusters.

This capability, in turn, supports novel distributed system architectures. Clusters of small satellites [15], each hosting a monolithic SWIR sensor-processor imaging, could form adaptive, reconfigurable observatories where the optical links used for precision metrology and formation flying also constitute the high-bandwidth data backbone. For deep-space exploration, an integrated SWIR system could manage the complete data chain— from collecting the spectral signature of a planetary atmosphere to transmitting the processed science data via a high-rate optical downlink. The inherent SWaP efficiency, robustness, and functional integration promised by the monolithic platform render these systemically elegant mission concepts not merely aspirational but a tangible goal for the coming decade.

Conclusion

In summary, the SWIR band represents more than a passive spectral region; it is an active arena of technological convergence between humanity’s exploratory and operational imperatives in space. GOI technology embodies a strategic, dual-path response to this convergence. Presently, hybrid integration via flip-chip bonding provides a mature, high-performance pathway, solidly supporting the immediate needs of advanced astronomy and communication missions. Concurrently, monolithic integration stands as the foundational long-term vector, functioning as a vehicle for deep systemic integration that directly confronts the mass, power, cost, and complexity bottlenecks constraining next-generation mission concepts. As the monolithic platform matures through ongoing materials and device innovation, it will catalyze an evolution from collections of discrete instruments toward unified, intelligent spatial platforms. The future SWIR landscape is thus envisioned not as a displacement of one technology by another, but as a strategic diversification and evolution.

High-performance III-V and hybrid-integrated Ge/GOI FPA will remain essential for missions at the absolute sensitivity frontier in the near to mid-term, while GOI-based monolithic integration will progressively unlock new realms where ultimate scalability, functional density, and system-level simplicity are paramount. Together, these complementary pathways will provide mission architects with a more versatile and powerful toolkit, enabling a more capable, connected, and profoundly insightful presence in the cosmos. Beyond the SWIR band, the advances in GOI-based photodetectors also highlight their potential for functional nearinfrared spectroscopy (fNIRs) applications. By leveraging the same principles of low-noise detection, scalable monolithic integration, and SWaP efficiency, future systems could enable compact, multifunctional optical sensing platforms for biomedical, cognitive, or life-science monitoring, bridging space-grade photodetection technology with terrestrial functional imaging [16]. This crossspectral applicability further underscores the broad relevance and adaptability of GOI technology.

Funding

Talent Plan” Innovation and Entrepreneurship Team Project of Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2021ZT09X479).

References

- Guellec F, Boulade O, Cervera C, Moreau V, Gravrand O, et al. (2017) ROIC development at CEA for SWIR detectors: Pixel circuit architecture and trade-offs. International Conference on Space Optics-ICSO 2014 10563: 155-163.

- Alsalem N, Betters CH, Mao Y, Cairns IH, Leon-Saval SG (2023) RedEye-1: a compact SWIR hyperspectral imager for observation of atmospheric methane and carbon dioxide. Optics Continuum 2(11): 2333-2347.

- Ferraro MS, Singh A, Zern ZT, Murphy JL, Mahon R, et al. (2025) 2.5 G large area avalanche photodiodes for free space optical communication. Free-Space Laser Communications 13355: 534-542.

- Majumdar AK (2022) Laser-Based Satellite and Inter-satellite Communication Systems: Advanced Technologies and Performance Analysis. Laser Communication with Constellation Satellites, UAVs, HAPs and Balloons PP. 199-229.

- Hållstedt J, Blomqvist M, Persson POÅ, Hultman L, Radamson HH (2004) The effect of carbon and germanium on phase transformation of nickel on Si1-x-yGexCy epitaxial layers. Journal of Applied Physics 95(5): 2397-2402.

- Kolahdouz M, Farniya AA, Di Benedetto L, Radamson HH (2010) Improvement of infrared detection using Ge quantum dots multilayer structure. Applied Physics Letters 96(21): 213516.

- Yu J, Zhao X, Miao Y, Su J, Kong Z, et al. (2024) High-performance Ge PIN photodiodes on a 200 mm insulator with a resonant cavity structure and monolayer graphene absorber for SWIR detection. ACS Applied Nano Materials 7(6): 5889-5898.

- Wang H, Kong Z, Tan X, Su J, Du J, et al. (2024) High-performance GeSi/Ge multi-quantum well photodetector on a Ge-buffered Si substrate. Opt Lett 49(10): 2793-2796.

- Duan X, Zhao X, Su J, Lin H, Zhou Z, et al. (2025) Enhanced responsivity in GOI photodetectors with engineered SiO2/Si3N4 DBR multilayers for next-generation SWIR imaging applications. Applied Surface Science 714: 164451.

- Du J, Zhao X, Miao Y, Su J, Li B, et al. (2025) Demonstration of Planar Geometry PIN Photodetectors with GeSi/Ge Multiple Quantum Wells Hybrid Intrinsic Region on a Ge-on-Insulator Platform. ACS Applied Electronic Materials 7(11).

- An Y, Jiao J, Chen G, Yao L, Wu S, et al. (2025) Hyper Self-Doping of GeIn for Cost-Effective Ge PIN Photodiodes with Record-Low Dark Current. ACS Photonics 12(5): 2868-2877.

- Zhang N, Hao Y, Shao J, Chen Y, Yan J, et al. (2023) Detection properties of Ge MSM photodetector enhanced by Au nanoparticles. IEEE Transactions on Electron Devices70(10): 5288-5293.

- Aliane A, Ouvrier-Buffet JL, Ludurczak W, André L, Kaya H, et al. (2020) Fabrication and characterization of sensitive vertical P-i-N germanium photodiodes as infrared detectors. Semiconductor Science and Technology 35(3): 035013.

- Yuan Y, Huang Z, Zeng X, Liang D, Sorin WV, et al. (2021) High responsivity Si-Ge waveguide avalanche photodiodes enhanced by loop reflector. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 28(2): 1-8.

- Casana J, Ferwerda C (2023) Archaeological prospection using WorldView-3 short-wave infrared (SWIR) satellite imagery: Case studies from the Fertile Crescent. Archaeological Prospection 30(3): 327-340.

- Miao Y, Radamson HH (2024) Functional Near-Infrared Imaging for Biomedical Applications. Recent Advances in Infrared Spectroscopy and Its Applications in Biotechnology.

-

Yuanhao Miao*, and Henry H Radamson*. From Hybrid Integration to Monolithic Integration: The Ge/GOI SWIR Pathway for Future Space Systems. Iris Jour of Astro & Sat Communicat. 2(2): 2025. IJASC.MS.ID.000526.

-

Short-wave infrared (SWIR); germanium-on-Insulator (GOI); monolithic integration; hybrid integration; space systems; iris publishers; iris publisher’s group

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.