Review Article

Review Article

Variation in Utilisation of NICU Across Tertiary Care Centers in Alain Region of Abudhabi, UAE: A Review

Nisha Viji Varghese*, Mohammad Khassawneh, Binu Pappachan, Javeria Bhatti and Uzma Afzal

Tawam Hospital, Alain, UAE

Nisha Viji Varghese, Tawam Hospital, Alain, UAE.

Received Date: November 13, 2021; Published Date: November 24, 2021

Abstract

Objectives: The current study was designed to evaluate the variation in patterns of admission of term and preterm infants across two tertiary care NICUs in Al Ain region of Abu Dhabi, UAE.

Methods: This study represents a population based examination of the epidemiological trends of NICU admissions over a two-year period between 1st January 2017 to 31st December 2019 at 2 tertiary care NICUs in the Al Ain region of Abu Dhabi UAE. A detailed form was created to collect information from the patient’s electronic medical records. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

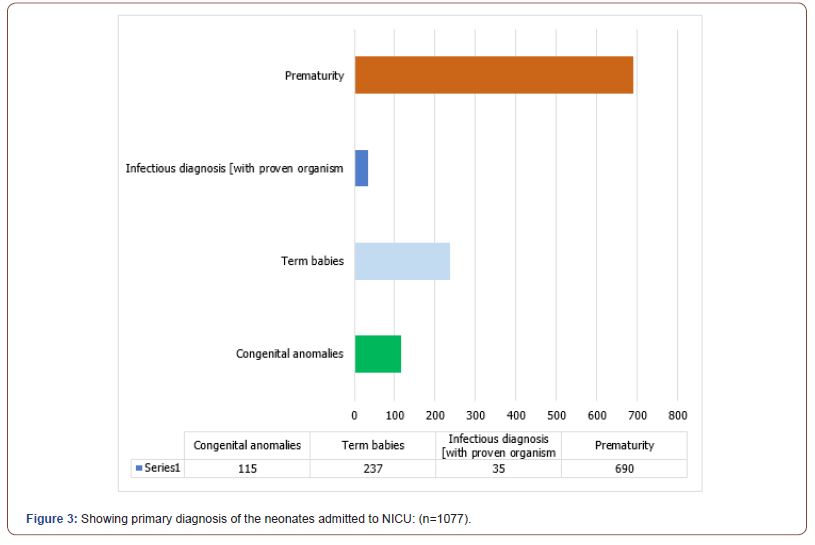

Results: A total of 1077 babies were admitted in the study period, with mean maternal age of 31.14±5.76 years. Majority 76.6% were multigravida, and 42.3% had spontaneous vaginal delivery. Among the admitted neonates, 56.8% were male babies. 483 babies had birth weight more than 2.5 kg while 594 had lower than 2.49 kg out of which 76 babies had birth weight less than 1 kg. 39.64% of the babies were >37 weeks’ gestation while 64.06% were less than 36 weeks. Only 14.4% required ventilation after initial oxygen support at birth. Regarding the primary diagnosis, 64.06% were admitted as case of prematurity, 22% term babies were admitted with different illness, 10.7% were with different congenital anomalies, and 3.24% with proven infectious diseases. The mean stay in NICU was 24.17±42.73 days, with minimum of 5 hours of stay to maximum of 390 days.

Conclusion: There needs to be a solidified effort in trying to focus neonatal care teams on using the NICU wisely so that appropriate use of intensive care for sick newborn infants can be assured. Also it needs to account to the local context and the needs of families. Regularization of monitoring and creation of an intermediary unit or transitional care units between mother and baby units and NICU for monitoring of babies could have a momentous impact, both on minimizing the length of stay in term and preterm neonates as well as use of NICU beds.

Keywords: Neonates; NICU; Admission; Sepsis; Preterm

Introduction

NICUs are built to treat sick newborns in the first month of life. It is assumed that certain degree of prematurity requires NICU stay secondary to the need of respiratory support, monitoring of apneas and nutritional support in the context of their inability to orally feed. UAE is one of the rapid developing nations, experiencing fast transformation especially with rapid advances in the medical field. Extensive variation in admission rates at NICUs in various intensive care units across the UAE has been found. Preterm births are associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. Preterm births were reported up to 6.3% in previous studies in UAE [1], while low birth weight rate has been reported as 9.4%, which is less than in adjacent nations of Yemen and Oman with rate of 18% and 13.7% respectively [2,3]. Other issues such as Low birth weight is mostly the consequence of preterm birth or due to other reasons such as intrauterine growth restriction [4]. Infants with low birth weight are greatly exposed to various health concerns like delay in growth, contagious infections and growth retardation, that may happen in early stages of life, infancy and eventually in late periods of life [5]. Term babies may also need to be admitted for other medical diagnoses including disorders that require intensive care management like septic shock, surgical emergencies such as volvulus or critical congenital heart disease that affect perfusion. Magnitude of bed uti lization per gestational age groups is an important data to be evaluated in every health care system which will help in quality improvement initiatives, cost cutting and efficiency. Data on bed, resource utilization and admission rates of preterm and term babies to the NICU in different neonatal units in the UAE is lacking. Therefore, the current study was aimed to describe the characteristics of babies admitted to tertiary level NICUs at Tawam hospital and Al Ain hospital, in Abu Dhabi region of UAE.

Material and Methods

This was a retrospective study which included all babies admitted to the NICU in Tawam hospital and at Al-Ain hospital from 1st January 2017 to 31st December 2019. The study was conducted after approval from the ethics committee. A detailed data sheet was created to collect information from the patient’s electronic medical records. Names and patient IDs were concealed. All physicians participating in the study submitted data on all infants admitted to their respective NICUs using uniform definitions including transfer to other centers. All data underwent check for quality and completeness of data manually by the primary investigator.

Any initial resuscitation included oxygen, mask/endotracheal ventilation, nasal continuous positive pressure, epinephrine, cardiac compressions, surfactant immediately after birth. Ventilation after initial resuscitation included conventional ventilation and high frequency ventilation. Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy was only measured among infants at least 36 weeks gestational age. Extreme prematurity was defined as gestational age less than or equal to 27 weeks. Very preterm infants were defined as gestational ages between 28 weeks 0 days to 32 weeks and 6 days. Preterm infants were defined gestational ages between 33 weeks 0 days and 34 weeks 6 days. Late preterm infants were defined as those between 35 weeks 0 days till 36 weeks 6 days. Early term infants were those between 37 weeks 0 days till 38 weeks 6 days. Term infants were those babies between 39 weeks 0 days till 40 weeks 6 days. Post term infants were those babies above or equal to 41 weeks.

High acuity was defined for infants born more than or equal to 34 weeks gestational age as follows: death, intubated or ventilated more than 48 hours, early bacterial sepsis, major surgery requiring anesthesia, transport to other center for surgical or medical services, HIE, 5 minute Apgar less than 5, therapeutic hypothermia. Length of stay was measured as the number of days from when the baby was admitted until the date of initial discharge from the hospital, transfer or death. Short stays were defined as infants more than equal to 34 weeks gestational age who were inborn and who stayed 1-3 days and were discharged from the hospital.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Continuous variables will be reported as mean and standard deviation and categorical variables as number (percent). Chi-square test and Pearson’s correlation test will be applied. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

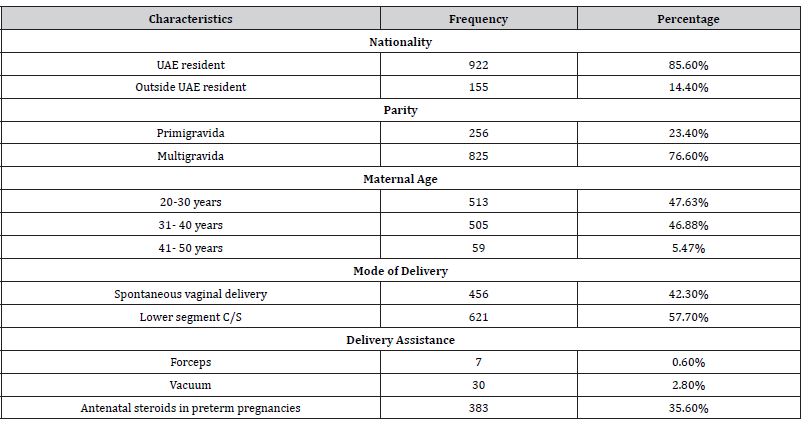

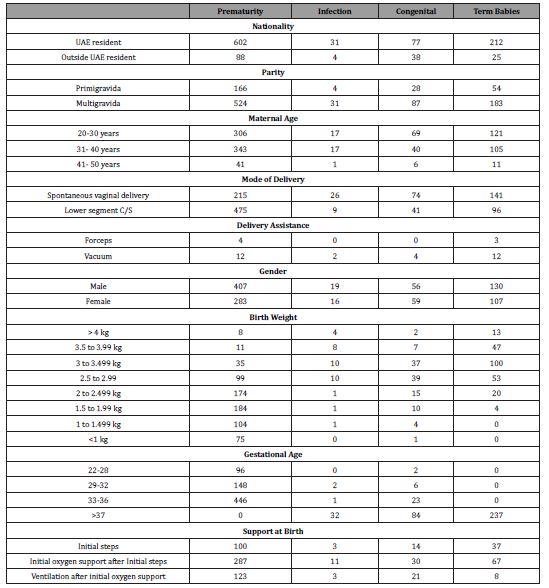

A total of 1077 babies were admitted in the study period, with mean maternal age of 31.14±5.76 years, with age range from 20-50 years. 85.6% were Emirati babies admitted to our unit primarily because we serve the national population mainly. Majority of the mothers were multigravida [76.6%], and 42.3% of them delivered via spontaneous vaginal delivery (Table 1).

Table 1:Maternal characteristics of NICU admission (n=1077).

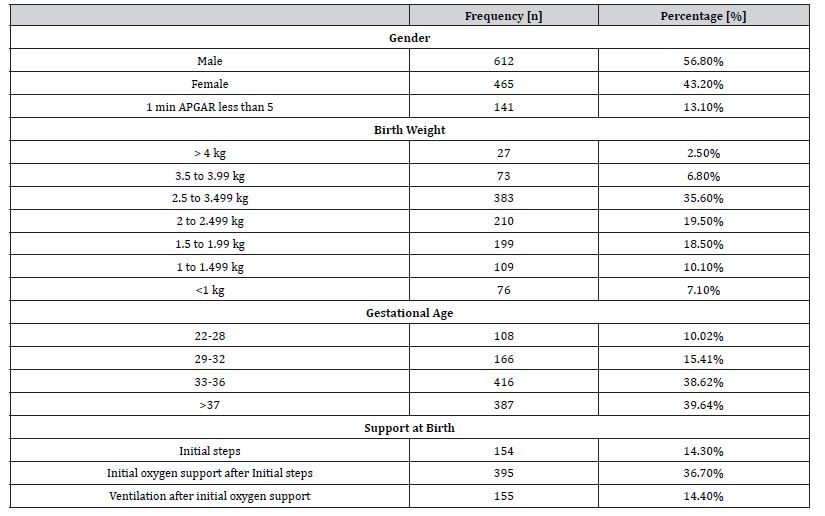

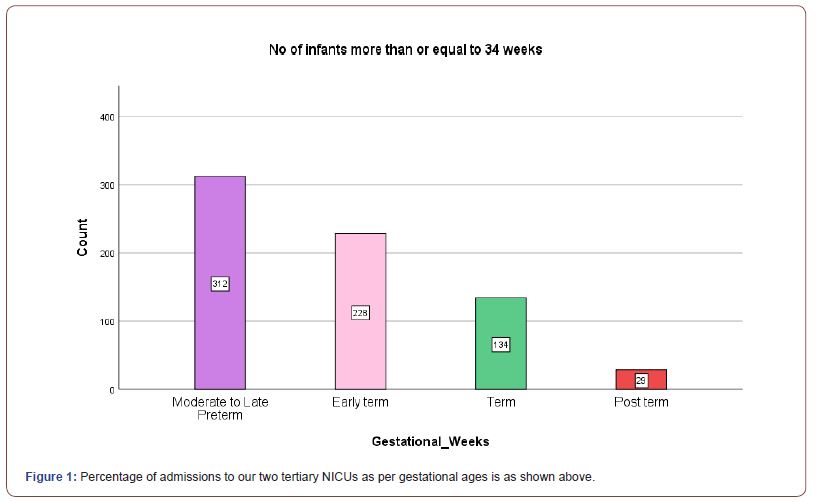

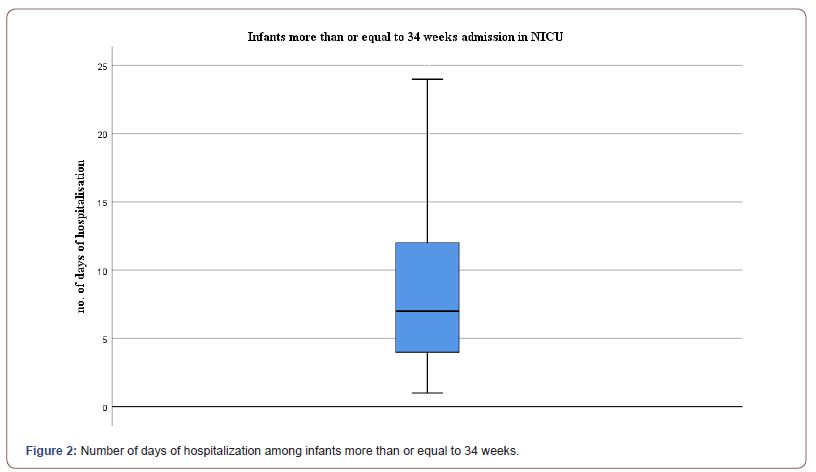

Among the admitted neonates, male babies were 56.8%, while rest were female, in which 141 babies had 1st minute APGAR lower than score 5. 483 of the total babies weighed more than 2.5 kg while 76 of the total babies had birth weight less than 1 kg. Out of 1077 patients, 39.64% were >37 weeks of gestation, while 64.06% were less than 36 weeks. Only 14.4% required ventilation after initial oxygen support following delivery (Figure 1&2), (Table 2).

Table 2:Characteristics of neonates admitted to NICU: (n=1077).

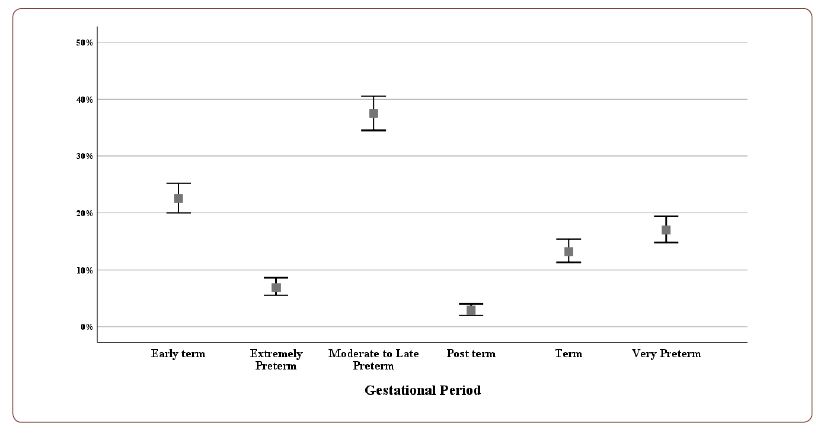

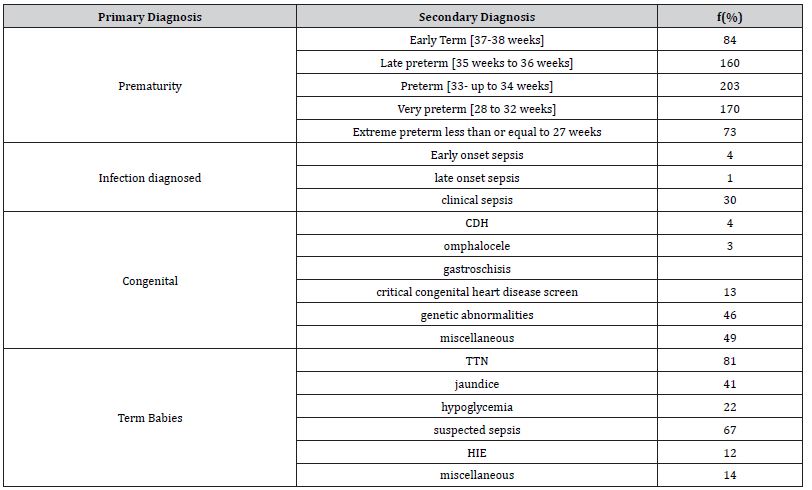

Regarding the primary diagnoses, out of a total of 1077 babies, 690 were admitted as case of prematurity, 237 term babies with different illness, 115 with different congenital anomalies, and 35 with proven infectious diseases. Figure 1 and table 3 below shows the various secondary diagnoses in admitted patients in NICU. The mean stay in NICU was 24.17±42.73 days, with minimum of only 5 hours of stay to maximum of 390 days (Figure 3), (Table 3&4).

Table 3:Secondary diagnosis of patients admitted to NICU (n=1077).

Table 4:Stratification of maternal and neonatal characteristics with primary diagnosis (n=1077).

Discussion

Selective advancements in neonatal intensive care units (NICU) were made in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) which have considerably increased survival ratio and decreased morbidity among newborn babies admitted to these NICUs. However, there are variations in utilization of NICU across tertiary care units in the UAE [6]. In our cross sectional study from January 2017 to December 2019 all of the 1077 babies were admitted to 2 tertiary NICUs at Tawam hospital and at Al-Ain hospital respectively. 85.6% were Emiratis while 14.4% were non Emiratis. Among the admitted neonates 56.8% were male while rest of them were female. The demographic report of patients admitted to Canadian NICUs also disclose the predominance of male infants (57.5%) which is similar to the reports by NICHD (49% male) [7] and the Vermont-Oxford Trials Network (51% male) as well [8]. The main strength of this study is the use of large sample size and its representatives. We described the incidence and burden of neonates in these NICUs and associated risk factors. Majority 76.6% were multigravida, and 42.3% had spontaneous vaginal delivery. In our study, 74.5% were babies born at gestational age ≥33 weeks, which is almost similar to the 74% and 80% reported in the Canada and United States [9,10].

Admission of infants to NICUs brings certain risk factors [11] and increase acute stress for the neonate’s families [12]. With our data regarding the primary diagnosis, 36% neonates carried various abnormalities. 3.2% of the total neonates were admitted with proven infectious diseases. The mean stay in NICU was 24 days in accordance with the previous studies [13,14]. 7% of all admitted neonates had a minimum single incidence of bacterial infection, which was confirmed by positive blood culture or urine culture or CSF culture. The incidence of infection was highest among infants with gestation age <28 weeks (30%) and low among infants with gestation ages between 33 to 37 weeks (3%) [15]. Despite the comparatively small variation in the neonatal characteristics, significant variations are observed in the follow up of infant groups homogenous for gestational age and merely moderate preterm [16]. We suggest that care units should monitor infant admissions by capacity, gestational age and related lengths of stay to better understand how features contribute to possible overuse in the confined context.

Length of stay at hospitalization in term and preterm neonates is greatly influenced by gestational age (GA) at birth and infant weight at the time of birth. The largest ratio of preterm babies admitted to NICUs are moderately preterm with comparatively minimum stays at hospitals. Variation in NICU utilization may have a huge effect on census of NICU and discharge period [17]. We limited our analysis to gestational age between 22-37 weeks which is pretty large as estimated in previous studies as well [17]. In our study 38.62% infants were born between 33-36 weeks while in contrast approximately 10% to 15% neonates born between 33-35 weeks 90 [18-35].

Our study concluded a significant variation in utilization of NICUs. A campaign to focus neonatal care takers on prudent use of NICU needs to be addressed. Regularization of monitoring follow up could have a momentous impact on minimizing the length of stay in term and preterm neonates [36-50].

Conclusion

A campaign is needed in the UAE to help focus on the prudent use of NICU so as to enable suitable use of tertiary level 3 NICU for really sick neonates. Efforts also need to be put in to create an observation area or transitional care area for babies who need minor help in transitioning at birth as well. Regularization of close follow up could have a momentous impact on minimizing the length of stay in term and preterm neonates.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Taha Z, Garemo M, Nanda J (2018) Patterns of breastfeeding practices among infants and young children in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. International breastfeeding journal 13: 48.

- Shuaib A, Frass K (2017) Occurrence and risk factors of low birth weight in Sana’a, Yemen. Journal of High Institute of Public Health 47(1): 8-12.

- Islam MM, Bakheit CS (2015) Advanced maternal age and risks for adverse pregnancy outcomes: a population-based study in Oman. Health care for women international 36(10): 1081-1103.

- Cutland CL, Lackritz EM, Mallett-Moore T, Bardají A, Chandrasekaran R, et al. (2017) Low birth weight: Case definition & guidelines for data collection, analysis, and presentation of maternal immunization safety data. Vaccine 35(48 Pt A): 6492-6500.

- Chedid F, Shanteer S, Haddad H, Musharraf I, Shihab Z, et al. (2009) Short-term outcome of very low birth weight infants in a developing country: comparison with the Vermont Oxford Network. Journal of tropical pediatrics 55(1): 15-19.

- Dawodu A, Varady E, Nath KN, Rajan TV (2005) Neonatal outcome in the United Arab Emirates: the effect of changes in resources and practices. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 11(4): 673-679.

- Stevenson DK, Wright LL, Lemons JA, Oh W, Korones SB, et al. (1998) Very low birth weight outcomes of the national institute of child health and human development neonatal research network, January 1993 through December 1994. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 179(6 Pt 1): 1632-1639.

- Balcom RJ, Helmuth WV, Beaumont E, Sutton D, Vollman J, et al. (1993) the vermont-oxford-trials-network-very-low-birth-weight outcomes for 1990. Pediatrics 91(3): 540-545.

- Edwards EM, Horbar JD (2018) Variation in use by NICU types in the United States. Pediatrics 142(5): e20180457.

- Schulman J, Braun D, Lee HC, Profit J, Duenas G, et al. (2018) Association between neonatal intensive care unit admission rates and illness acuity. JAMA pediatrics 172(1): 17-23.

- Testoni D, Hayashi M, Cohen-Wolkowiez M, Benjamin Jr DK, Lopes RD, et al (2014). Late-onset bloodstream infections in hospitalized term infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J 33(9): 920-923.

- Hynan MT, Mounts KO, Vanderbilt DL (2013) Screening parents of high-risk infants for emotional distress: rationale and recommendations. Journal of Perinatology 33(10): 748-753.

- Harrison W, Goodman D (2015) Epidemiologic trends in neonatal intensive care, 2007-2012. JAMA pediatrics 169(9): 855-862.

- Ziegler KA, Paul DA, Hoffman M, Locke R (2016) Variation in NICU admission rates without identifiable cause. Hospital pediatrics 6(5): 255-260.

- Lee SK, McMillan DD, Ohlsson A, Pendray M, Synnes A, et al. (2000) Variations in practice and outcomes in the Canadian NICU network: 1996–1997. Pediatrics 106(5): 1070-1079.

- McCormick MC, Escobar GJ, Zheng Z, Richardson DK (2006) Place of birth and variations in management of late preterm (“near-term”) infants. Seminars in perinatology 30(1): 44-47.

- Eichenwald EC, Zupancic JA, Mao WY, Richardson DK, McCormick MC, et al. (2011) Variation in diagnosis of apnea in moderately preterm infants predicts length of stay. Pediatrics 127(1): e53-e58.

- Barker DJ, Eriksson JG, Forsén T, Osmond C (2002) Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. International journal of epidemiology 31(6): 1235-1239.

- Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Chu Y, Perin J, et al. (2016) Global, regional, and national causes of under-5 mortality in 2000–15: an updated systematic analysis with implications for the Sustainable Development Goals. The Lancet 388(10063): 3027-3035.

- Gardner H, Green K, Gardner AS, Geddes D (2018) Observations on the health of infants at a time of rapid societal change: a longitudinal study from birth to fifteen months in Abu Dhabi. BMC pediatrics 18(1): 1-9.

- Dawodu A (2000) Neonatal audit in the United Arab Emirates: a country with a rapidly developing economy. EMHJ-Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 6(1): 55-64.

- Wagura P, Wasunna A, Laving A, Wamalwa D, Ng'ang'a P (2018) Prevalence and factors associated with preterm birth at kenyatta national hospital. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 18(1): 107.

- World Health Organization (2014) Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Low birth weight policy brief. (No. WHO/NMH/NHD/14.5). World Health Organization.

- Taha Z, Ali Hassan A, Wikkeling-Scott L, Papandreou D (2020) Factors associated with preterm birth and low birth weight in Abu Dhabi, the United Arab Emirates. International journal of environmental research and public health 17(4): 1382.

- Thyoka M, Eaton S, Hall NJ, Drake D, Kiely E, et al. (2012) Advanced necrotizing enterocolitis part 2: recurrence of necrotizing enterocolitis. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 22(01): 13-16.

- Gardner H, Green K, Gardner AS, Geddes D (2018) Observations on the health of infants at a time of rapid societal change: a longitudinal study from birth to fifteen months in Abu Dhabi. BMC pediatrics 18(1): 1-9.

- Henderson‐Smart DJ (1981) The effect of gestational age on the incidence and duration of recurrent apnoea in newborn babies. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 17(4): 273-276.

- Horbar JD, Carpenter JH, Badger GJ, Kenny MJ, Soll RF, etal. (2012) Mortality and neonatal morbidity among infants 501 to 1500 grams from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics 129(6): 1019-1026.

- Soll RF, Edwards EM, Badger GJ, Kenny MJ, Morrow KA, et al. (2013) Obstetric and neonatal care practices for infants 501 to 1500 g from 2000 to 2009. Pediatrics 132(2): 222-228.

- Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, et al. (2015) Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA 314(10): 1039-1051.

- Ellsbury DL, Clark RH, Ursprung R, Handler DL, Dodd ED, et al. (2016) A multifaceted approach to improving outcomes in the NICU: the Pediatrix 100 000 Babies Campaign. Pediatrics 137(4): e20150389.

- Murthy K, Dykes FD, Padula MA, Pallotto EK, Reber KM, et al. (2014) The Children’s Hospitals Neonatal Database: an overview of patient complexity, outcomes and variation in care. J Perinatol 34(8): 582-586.

- Griffin IJ, Lee HC, Profit J, Tancedi DJ (2015) The smallest of the small: short-term outcomes of profoundly growth restricted and profoundly low birth weight preterm infants. J Perinatol 35(7): 503-510.

- Goodman DC, Little GA (2018) Data deficiency in an era of expanding neonatal intensive care unit care. JAMA Pediatr 172(1): 11-12.

- Dukhovny D, Pursley DM, Kirpalani HM, Horbar JH, Zupancic JA (2016) Evidence, quality, and waste: solving the value equation in neonatology. Pediatrics 137(3): e20150312.

- Ho T, Dukhovny D, Zupancic JA, Goldmann DA, Horbar JD, et al. (2015) Choosing wisely in newborn medicine: five opportunities to increase value. Pediatrics 136(2): e482-e489.

- Vermont Oxford Network (2015) Manual of Operations for Infants Born in 2016. Vol 20. Burlington, VT: Vermont Oxford Network.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newborn (2012) Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics 130(3): 587-597.

- (2013) ACOG committee opinion no 579: definition of term pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 122(5): 1139-1140.

- Polin RA, Denson S, Brady MT, Committee on Fetus and Newborn (2012) Committee on Infectious Diseases. Epidemiology and diagnosis of health care-associated infections in the NICU. Pediatrics 129(4): e1104-e1109.

- Sekar KC (2010) Iatrogenic complications in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol 30(suppl): S51-S56.

- Celenza JF, Zayack D, Buus-Frank ME, Horbar JD (2017) Family involvement in quality improvement: from bedside advocate to system advisor. Clin Perinatol 44(3): 553-566.

- Harrison WN, Wasserman JR, Goodman DC (2018) Regional variation in neonatal intensive care admissions and the relationship to bed supply. J Pediatr 192: 73-79.

- Freedman S (2016) Capacity and utilization in health care: the effect of empty beds on neonatal intensive care admission. Am Econ J Econ Policy 8(2): 154-185.

- Carroll AE (2015) The concern for supply-sensitive neonatal intensive care unit care: if you build them, they will come. JAMA Pediatr169(9): 812-813.

- LeBlanc S, Haushalter J, Seashore C, Wood KS, Steiner MJ, et al. (2018) A quality-improvement initiative to reduce NICU transfers for neonates at risk for hypoglycemia. Pediatrics 141(3): e20171143.

- Clark SL, Frye DR, Meyers JA, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, et al (2010) Reduction in elective delivery at <39 weeks of gestation: comparative effectiveness of 3 approaches to change and the impact on neonatal intensive care admission and stillbirth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 203(5): 449.

- Joshi NS, Gupta A, Allan JM, Cohen RS, Aby JL, et al. (2018) Clinical monitoring of well-appearing infants born to mothers with chorioamnionitis. Pediatrics 141(4): e20172056.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP NICU verification program.

- Escobar GJ, Puopolo KM, Wi S, Turk BJ, Kuzniewicz MW, et al (2014) Stratification of risk of early-onset sepsis in newborns ≥ 34 weeks’ gestation. Pediatrics 133(1): 30-36.

-

Nisha Viji Varghese, Mohammad Khassawneh, Binu Pappachan, Javeria Bhatti and Uzma Afzal. Variation in Utilisation of NICU Across Tertiary Care Centers in Alain Region of Abudhabi, UAE: A Review. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 3(5): 2021. GJPNC.MS.ID.000575.

Neonates, NICU, Admission, Sepsis, Preterm, Tertiary care, Abudhabi, Patient, Babies, Gestational age, Infectious diseases, UAE, Tawam hospital, Population, Ventilation, Prematurity, Risk factors

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.