Mini Review

Mini Review

Sudden Cardiac Death in Adolescent Athletes

Matthew Stark*

Director of Transfusion Services, Children’s Hospital New Orleans, USA

Matthew Stark, Director of Transfusion Services, Children’s Hospital New Orleans, 200 Henry Clay Ave, New Orleans, LA 70118, USA.

Received Date: June 10, 2020; Published Date: June 18, 2020

Introduction

Adolescent death is distressing to the family and community no matter the cause, and the sudden death of an adolescent participating in athletics is shocking. Pathologists have found that most sudden unexplained deaths (SUD) of the adolescent are associated with a hereditary condition, of which cardiovascular diseases are the most frequent. Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the most common cause of death in the adolescent athlete and is an important unsolved challenge in the practice of pediatrics.

General Health

The 2019 US Census data tells there are 41,676 total children in the US from 10-19 years old, making them 13% of the US population. In a national survey > 80% of adolescents say they are in excellent or very good health and only about 5% of adolescents missed more than 11 days of school due to illness or injury in the previous 12 months [1].

What are the causes of death in otherwise healthy adolescents dying suddenly while engaged in athletics? Of the top ten causes of death for adolescents, most are either traumatic or have an identifiable prodromal symptomology before the fatal event. Seizures, asthma, pulmonary embolism, and intercranial bleeds can be mechanisms of death in athletic adolescents, but nearly twothirds of sudden deaths in adolescents are attributable to sudden cardiac death.

Epidemiology

Sudden cardiac death in the adolescent is uncommon. Good numbers for adolescents only are not available, but <100 American athletes under the age of 35 have succumbed to SCD each year. The highest number athlete deaths in the under 35 age group was 76 in 2006. The NCAA released five year tracking numbers and found 45 SCD in 273 total deaths, making the incidence 1: 43,770 participants per year. For perspective, SCD in young athletes is about as common as lightning fatalities.

Sudden Cardiac Death

In adults, coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common cause of SCD. “Premature CAD” is much less common in adolescents. Familial hypercholesterolemia may result in diffuse atheroma of the coronary arteries, leading to blockage and myocardial ischemia. One consultant in the UK saw an 11 year old asymptomatic female “drop dead” after a cross country run. Subsequent investigation found a strong family history of hypercholesterolemia. Much more common in adolescent athletes are non-atheromatous coronary artery anomalies (CAA), including anomalous coronary arteries, coronary artery dissection, coronary artery vasculitis and coronary artery fistula. These anomalies are often asymptomatic with one study finding 60% of affected adolescents having no syncopal episodes or chest pain on exertion before SCD. CAA are the second most common cause of SCD in young athletes and are found in about 1% of the general population [2].

Cardiomyopathies are the most common cause of SCD in young athletes and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most frequent form in US athletes. In the general population, nearly 1 in 500 people are thought to be affected, with males and females having equal incidence. HCM is an inherited disease more widespread in African-American athletes, with the mutation found in the cardiac sarcomere. There are 11 identified genes contributing to HCM, with > 1,000 identified mutations within those genes. Clinical recognition of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is enhanced by two-dimensional echocardiogram which will demonstrate an unexplained asymmetric left ventricular wall thickening.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is another genetic cardiomyopathy with fibrous/fatty replacement of the heart muscle associated with ventricular tachycardia and sudden death in young people, especially athletes. ARVC principally involves the right ventricle (RV), but the left ventricle is often involved and there is support for adoption of the broad term arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Fibrofatty replacement of the RV inferior, apical, and infundibular walls usually starts at the epicardium and extends toward the endocardium with many examples becoming completely transmural.

Establishment of a diagnosis of a heritably transmitted cardiovascular disease has implications for family members. Nextgeneration sequencing (NGS) and Massively Parallel Sequencing (MPS) have revolutionized cardiovascular genetics, making molecular diagnosis for genetic cardiomyopathies practicable. Multiple reference databanks exist, commercial labs offer several panels of candidate genes.

If a pathogenic mutation is documented, relatives could be approached to test for the specific abnormal gene. This approach is termed targeted cascade screening and is thought to provide a greater rate of detection than general population screening. If possible, the living family member would undergo complete cardiological and genetic assessment by a multidisciplinary team consisting of members of genetics, cardiology, and the psychosocial support system. Genetic counseling could highlight the advantages (preventative measures) and disadvantages (subsequent insurance cost increase) of testing. Expert opinion has concluded that if no disease-associated mutation is identified, then evaluation may involve cardiologic examination only. The purpose behind this cascade screening is to reduce SCD in family members, using the successful model of the familial cancer screening programs.

At our own institution, communication between outside physicians and Children’s Hospital Department of Pathology has resulted in the successful collection of high-quality DNAs at the time of autopsy, allowing postmortem cardiomyopathy genetic testing. Regrettably, molecular diagnostic testing is performed in very few cases of SCD because of cost. Reimbursement for postmortem molecular testing is rarely covered by insurance companies regardless of consequences for relatives.

It is not clear if current youth athletic activity screening strategies are effective in identifying precursor cardiac lesions for SCD. Mass screenings of the general pediatric population have been undertaken in Japan and Taiwan, with associated high costs. The Japanese children were initially examined by history-taking and a resting 12-lead ECG, with detected abnormalities examined by a cardiologist, but some diagnoses were missed, resulting in unexpected SCD. The Japanese estimated they spent $ 8,800 per year of life saved.

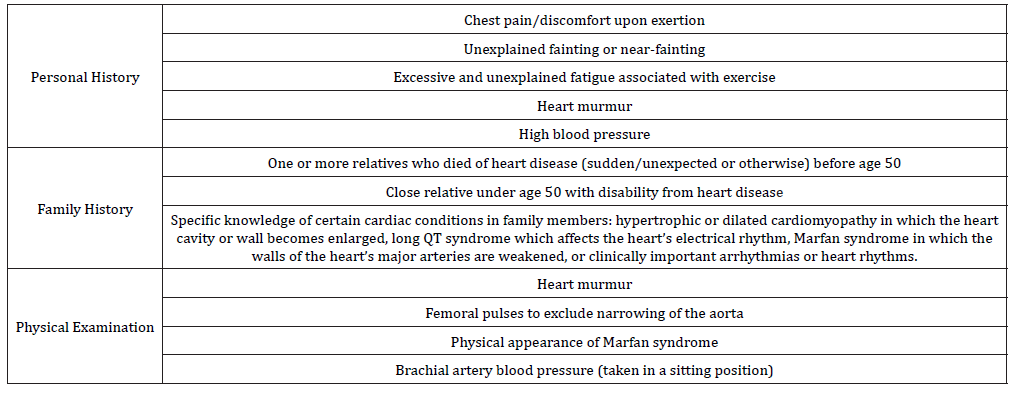

Table 1:American Heart Association 12-step screening for reduction of sudden death in young athletes.

No national standard for either healthcare professional certifications or screening standards for high school or college athletes exist. 39 states have a medical clearance form needing at least a history and physical (H&P) examination, meaning 11 do not even require this. In our state, Louisiana High School Athletic Association (LHSAA) Medical Evaluation Form is an H&P form that may be filled by MD, DO, Advanced Practice Registered Nurse or Physician’s Assistant. Expert consensus finds pre participation screening by H&P alone is not enough for detecting life-threatening cardiovascular anomalies in adolescent athletes, and the benefit of a 12 lead EKG is not clear. The mass screenings of American adolescents is not cost effective. Maron et al. [3], representing the American Heart Association, recommend adolescents have a pre participation examination every two years (Table 1) and a medical history taken in the year between. Additional tests including EKG and Echocardiogram are not recommended for screening but may be used by specialists if an abnormality is detected at pre participation screening.

Summary

Adolescent non-traumatic death frequently involves SCD. Although SCD is an uncommon event in young athletes, HCM and CAA are the leading mechanisms in that order. ARVC and HCM have a genetic component, but postmortem molecular diagnosis is rarely performed because of cost and lack of insurance reimbursement. Mass population screening is associated with high costs and occasionally missed diagnoses.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- US Census Bureau, Department of Commerce (2019) Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement. USA.

- Fuller CM (2000) Cost effectiveness analysis of screening of high school athletes for risk of sudden cardiac death. Med Sci Sports Exerc 32(5): 887-890.

- Maron Barry J, Thompson Paul D, Ackerman Michael J, Balady Gary, Berger Stuart, et al. (2007) Recommendations and Considerations Related to Preparticipation Screening for Cardiovascular Abnormalities in Competitive Athletes: 2007 Update A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism: Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation 115(12): 1643-1655.

-

Matthew Stark. Sudden Cardiac Death in Adolescent Athletes. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 2(3): 2020. GJPNC.MS.ID.000539.

Sudden cardiac death, Athletes, Adolescents, Population, Family, Health, Children, Young athletes, HCM, Disease, Screening, Cardiomyopathy

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.