Research Article

Research Article

Neonatal Survival Improvement in Dominican Republic through effective Collaboration of the Iberoamerican Society of Neonatology (SIBEN)

Augusto Sola1*, Marcelo Cardetti2, Taína Malena3, María Teresa Montes Bueno4, Chanel Rosa Chupany5 and Susana Rodríguez6

1Medical Director, Iberoamerican Society of Neonatology (SIBEN)

2Chief of Neonatology, Clinic and Maternity Center for Endocrinology and Human Reproduction, Argentina

3Chief of Neonatology, National Health Service, Dominican Republic

4Neonatology Department, La Paz University Hospital, Madrid, Spain

5General Director, National Health Service, Dominican Republic

6Director of Research and Education, Hospital Juan P Garrahan, Argentina

Augusto Sola, Executive Medical Director -Iberoamerican Society of Neonatology (SIBEN), 2244 Newbury, Dr Wellington Fl, USA.

Received Date: April 03, 2020; Published Date: April 14, 2020

Abstract

Background: The Iberoamerican Society of Neonatology (SIBEN) dedicates efforts to facilitate the dissemination of knowledge and contributes to the well-being of NB in the Latin American region. In the Dominican Republic, the neonatal mortality rate was 17‰ in 2018, among the highest in Latin America. Through an agreement between the National Health System (NHS) of the country and SIBEN, actions were planned, developed and implemented to improve care of sick newborns (NB) at risk of dying.

Objective: To describe the actions implemented and to present the results obtained in the first year of collaborative work.

Methods: Multidimensional interventions in the context of continuous quality improvement of care in all public hospitals of the country where neonatal care is delivered. The main components of the comprehensive program were: detailed monitoring of vital statistics; situational diagnosis working in the field, including assessment of clinical management and procedures, education, NB and family issues, staff issues, infrastructure, equipment, and legal/regulatory and ethical issues, in order to institute an appropriate “hierarchy of interventions”. In addition, we performed root cause analysis (RCA) in deceased NB and incorporated data collection system in the neonatal units through SIBEN’s neonatal network. Finally, we also performed a preliminary cost analysis.

Results: The country’s neonatal mortality rate decreased from 17‰ in 2018 to 12.1‰ in 2019, with a relative risk reduction of 26%. There were improvements in infrastructure, equipment and staffing, together with modifications in clinical management and procedures and education and training. More than 600 neonatal health care professionals were trained, including nurses, neonatologists and neonatology residents.

By root cause analysis (RCA), of 511 infants who died, 54% were <1500 grams and pulmonary hemorrhage (PH) was the most frequent cause.

During 2019, 3,347 NB were admitted to 11 neonatal intensive care units (NICU) hospitals and reported to SIBEN’s Network. Comparing data from the first semester of 2019 with the second semester, mortality in the NICU’s decreased from 22.5% to 19%, detection of significant patent ductus arteriosus improved and PH frequency decreased. The cost of the program was approximately 1,100 dollars per each of the newborn whose life was saved.

Conclusion: One year after the collaborative agreement between SIBEN and NHS started, organization and delivery of care to sick NB in public hospitals of the Dominican Republic improved, and has led to a significant increase in neonatal survival. This was due to education and to definite improvements in the provision of neonatal intensive care, in a cost-effective manner.

Keywords: Neonatal mortality; Education; Neonatal health services

Abbreviations: NHS: National Health Service of the Dominican Republic; SIBEN: Iberoamerican Society of Neonatology; NB: Newborn; PH: Pulmonary hemorrhage; RCA: Root cause analysis; NICU: Neonatal intensive care unit

Introduction

In the Dominican Republic the population is 11,000,000, the birth rate is 18‰, with about 180,000 births per year [1], and the neonatal mortality in previous years has been >18‰. Of all births, 14% of NB are of low birth weight (<2,500 grams) and 1.5-2.3% are <1,500 grams. These rates are higher than the average for Latin America and the Caribbean [1,2]. More than 74% of children who die before 12 months of age are ≤ 28 days old [1]. In the first half of 2018, of a total of 1,961 infant’s deaths, 1,461 (74.5%) occurred before 28 days of age [1].

In this country >98% of births occur in hospitals [1,2] and two years ago, two maternity hospitals with a high number of births reported a very high neonatal mortality rate, 31-39‰ [3]. Likewise, the caesarean section rate in the Dominican Republic is >65% [4], with higher rates in the private sector than in the public sector.

In its mission to implement actions to reduce neonatal mortality rates, the National Health System (NHS) incorporated concrete measures to improve neonatal care. Among them, on October 31, 2018, they called upon SIBEN to collaborate in the efforts to improve the care of sick and at-risk neonates through various actions, including education of neonatal health care professionals. The agreement was signed by the general director of the NHS, Mr Chanel Rosa Chupany and the medical director of SIBEN, Augusto Sola.

SIBEN is a non-profit and public charity organization registered in the United States, under the federal tax and legal regulations of that country. Its main mission is to collaborate to improve neonatal care through education in the Latin American region [5]. In accordance with its bylaws, SIBEN dedicates its efforts to the diffusion of knowledge with an ethical approach, including equity, intersectoral and interdisciplinary methodologies, in order to identify and implement medical, human and social solutions for sick NB and their families. This has been done through various faceto- face and interactive educational methods in multiple regions of Latin America as demonstrated in multiple publications, some of which are listed in the bibliographic references [6,9].

The social, economic, preventive and nutritional actions that can have an effective impact in improving neonatal morbidity and mortality, if properly implemented, are multiple and have been described in detail [10-12]. Within this exhaustive and comprehensive framework, SIBEN focuses fundamentally on one aspect, aiming its actions directly towards improving the quality of intra-institutional care in three key periods for NB’s at risk of dying: the immediate prenatal period, the fetal-neonatal transition period and during the stay in neonatal intensive care. To do this, it implements and adapts, according to local needs and possibilities, programs to improve the quality of direct care, which have been widely described by others [13-19].

Objective

Describe the actions implemented by SIBEN in the Dominican Republic within the agreement with the NHS and present results obtained that led to the improvement of neonatal quality of care and neonatal survival in a cost-effective manner.

Methods

The program started at the end of 2018 within the framework of the SIBEN-NHS agreement and was based on the search for strategies and the implementation of actions to improve neonatal survival in the Dominican Republic by 2019.

All complex health interventions require a multidimensional approach and for this we established stages of diagnosis, planning and specific actions. The modality of the interventions was developed following the procedures described for the continuous improvement of quality of care [13-19]. As proposed by Deming and Shewhart, the “PDSA” cycle involves planning, doing, studying and acting [12]. These iterative cycles are based on the application of the best available evidence, the comparative evaluation of the results with permanent feedback and a collaborative process of mutual learning across all institutions. For all the stages we planned a dynamic interaction in order to adapt the strategies to the reality of each institution, to the identified findings and to the feasibility of change. We developed a “road map” that included the components described in this manuscript, actions to be implemented for each and their expected results. We summarize below the methods used related to vital statistics and neonatal survival, situational diagnosis, education, and information systems.

Vital statistics and neonatal survival

Number of births, neonatal mortality and prematurity rates were obtained from the General Epidemiology System (GEPIS) of the Ministry of Public Health (MPH) of the Dominican Republic [1]. We used these data to compare 2018 (pre-intervention) with 2019 (intervention in course). Statistical analysis included measures of effect with their respective confidence intervals.

Situational diagnosis

We planned to evaluate various basic aspects related to quality of neonatal care in the following areas: a) infrastructure, equipment and supplies (availability of O2 and compressed air, blenders, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), surfactant, respirators and others; b) human resource endowment and education (doctors, nurses and residents); c) use of protocols and procedures (name of the NB, family access, and diagnosis and treatment of prevalent diseases, including neonatal sepsis). This was carried out by SIBEN neonatologists and nurses in the maternity wards with the highest number of deliveries, in order to identify priority situations to be modified. The analysis of all the reports was carried out together with the local responsible MD’s and RN’s.

Education (October 2018 - December 2019)

Educational actions were planned according to SIBEN programs. The following were adapted locally so that most doctors and nurses could participate:

Dialogues SIBEN: An educational activity for doctors and nurses with an interactive and participatory approach.

Field activities (hospital visits): Sequential visits to all maternity wards to improve and modify management guidelines in inpatient care.

Residents: In agreement with the Ministry of Public Health and the Autonomous University, a training program was developed for all neonatology residents, in person or remotely, for training in neonatal topics relevant to neonatal survival.

Nursing: the SIBEN nursing chapter designed educational activities in practical workshops and in the field to improve the care of the NB and the performance of procedures.

Information systems

As the continuous improvement cycles require a fairly rapid sequence of “data - information - action”, we established two additional mechanisms for information, in addition to the evidence provided by GEPIS: i) analysis of neonatal deaths according to the standardized techniques of root cause analysis method [20,21], and ii) systematized data through SIBEN’s Neonatal Network.

Root cause analysis (RCA): A service that SIBEN offers at no cost to SIBEN members. The objective is to establish why the death of a NB occurred and to identify the possible root causes that can be modified, to subsequently design improvement strategies with priority levels. Those in charge of data collection receive training in the use of web templates and in RCA techniques, guaranteeing the confidentiality and veracity of the data collected. Causes of death are classified as: a) unavoidable or inevitable, b) potentially reducible, and c) untimely. Inevitable death is considered one when an intrinsic unsalvageable condition of the NB is related to the death; potentially reducible, when some modification in the diagnostic or therapeutic process can modify the outcome; untimely or inopportune, if the moment of death was unexpected due to deficit or excess of therapeutic measures. The data were analyzed by SIBEN in a dissociated manner using descriptive summary statistics and graphs. All units were identified by letters to maintain confidentiality, and each unit received its own unit’s analysis at the end of the study.

SIBEN neonatal network

The SIBEN Neonatal Network is free of charge and includes the platform for data loading and both the global analysis and the individual analysis of each unit. It constitutes a confidential cooperation mechanism between neonatal centers in Latin America, where each unit maintains its independence and autonomy. Participation is voluntary and the objective is to facilitate the continuous improvement of quality of care, with the possibility of comparative evaluation or benchmarking with other units. It was planned to incorporate at least 11 units from the Dominican Republic, to have representative data and to be able to make comparisons of various indicators between the 1st and 2nd semester of 2019.

Cost analysis

For the last 2 months of 2018 and for all of 2019, we analyzed the costs of the three more costly components of the program: travel and lodging of SIBEN’s educators, new staff employed (MD’s and RN’s) and equipment. To assess cost-effectiveness, the total dollar amount was divided by the number of lives saved and also by an estimation of the number of years of lived saved.

Results

Vital statistics and neonatal survival

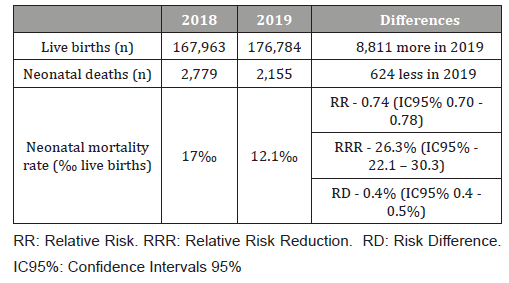

In 2019 there was a significant increase in neonatal survival compared to 2018. In 2018, there were 167,973 live births and 2,779 of them died, for a mortality rate of 17‰ live births with a prematurity rate of 8.6%. In 2019, there were 176,784 births, which meant an increase of 8,811 live births/year, with the same prematurity rate. Despite the increase in total births, there were 624 fewer newborn babies who died. The total number of neonatal deaths was 2,155, for a mortality rate of 12.1‰ live births, with a significant risk reduction in neonatal mortality of 26% (Table 1).

Table 1:Neonatal survival in Dominican Republic: Comparison of 2019 with 2018. [From General Epidemiology System [1]].

Situational diagnosis

The most significant aspects are summarized below:

a) Use of an exogenous surfactant without peer reviewed publications of pharmacodynamics, effectiveness and safety.

b) Protocol for management of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) endorsed by the Ministry of Health, with weaknesses in both diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

c) Infrastructure, equipment and supplies: absence of compressed air in 90% of the participating units and lack of blenders.

d) Lack of systems for CPAP or use of an inadequate system without adequate pressure delivery.

e) Human resources, quantity and education: deficit of nursing personnel well versed in neonatal intensive; high number of residents in training directly responsible for the care of critically ill NB without adequate supervision.

f) Other: newborn infants with no first name, early discharges without adequate planning, absence of diagnosis of patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) in premature infants, lack of utilization of peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC) and deficits in monitoring and transfer.

In this context, from the end of 2018educational activities were started (see 3 below) to improve neonatal care based on best available evidence [22,23]. The following results were achieved throughout 2019:

a) New protocol for management of RDS.

b) Use of exogenous surfactant of proven effectiveness and safety, approved by FDA.

c) Equipment and supplies: together with NHS personnel, we prepared detailed documents of several products for their acquisition through public bidding. Among them were: oxygen blenders, CPAP, pulse oximeters, X-ray equipment, monitors, ventilators, and echocardiographs for level II-IV NICU’s.

d) Provision of compressed air to the NICU’s in a sequential manner.

e) Increase in staff: 40 neonatologists and 150 nurses were recruited for different units.

In this first 3 months of 2020, we continue to collaborate in procedural changes, including: overall improvement of neonatal care in identification processes, resuscitation in the delivery room, hand washing, transport, nutrition, no risky early hospital discharges, incorporation of the use of PICC and decreasing limiting factors for parents’ visitation [24], among others.

Education

From October 2018 to February 2020, SIBEN has trained more than 500 professionals dedicated to neonatal care: 255 nurses, 120 neonatal residents and 184 neonatologists, out of the 15 hospitals that register the highest number of births in the country. Three “Neonatal Dialogues” of 3 days duration each with 300-350 participants (doctors and nurses) were carried out. Additionally, 10 workshops with the participation of neonatologists, residents and nurses with emphasis on some aspects including respiratory therapy, prevention and management of PDA and PH and infection prevention, among others. Moreover, visits to 11 hospitals were made in 34 opportunities with clinical-educational activities in the field, always with the joint participation of neonatologists, nurses and residents.

In February 2019 we started with the program designed exclusively for the 120 neonatology residents of the country (“Resi SIBEN”), with key themes to improve survival. In addition, 3 remote videoconferences were held through synchronous classrooms to address topics such as nasal ventilation, use of oxygen devices and fluid and electrolytes management.

For nursing: 3 theoretical-practical workshops for 170 nurses each, with training in Neurodevelopmental care, CPAP management and mechanical respiratory assistance, procedures, PICC and general care of the sick RN, including access of families to the NICU [24].

Information systems

RCA: Between February and July 2019, 511 neonatal deaths from 11 maternity wards were analyzed. The mean birth weight was 1650±928 grams (median 1307 grams) with a gestational age of 31±5 weeks. A total of 173 RN (34%) required resuscitation at birth, and 51(10%) of them received advanced resuscitation. Of the 511 neonatal deaths, 54% weighed <1500 grams at birth and 23% >2500 grams; 64% of the deaths occurred in the first week of life. Of the 326 premature infants ≤34 weeks of gestation who died, 133(40%) did not receive prenatal corticosteroids. In 43(8%) of the mothers there was no prenatal care and in 252(49%) the prenatal care was with ≤4 visits.

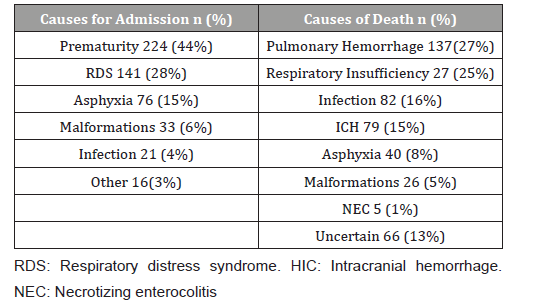

Table 2 shows that, although the main causes of hospitalization were prematurity and respiratory distress, PH was the most frequent cause of death (27%, Table 2). Respiratory failure, infection, and cerebral hemorrhage were also frequent causes. In 13% of the infants who died, the specific cause of mortality could not be specifically identified (Table 2).

Table 2:Causes of Admission and Deaths in 11 Neonatal Units in Dominican Republic by Root Cause Analysis, February-June 2019 (n: 511 neonatal deaths).

Strategies and actions were planned for PH, respiratory distress and infection as they were the main causes of mortality.

Complications during hospitalization occurred in 82% of deceased infants. The main ones were respiratory (64%) and infectious complications (36%). Furthermore, among the NB who died, 39% of the referrals requested and 24% of the specialized consults required were not satisfied. Of all deaths, 67% (341 of 511) were considered reducible and 48% (246) were inopportune or untimely.

The main shortfalls or problems identified related to the cause of death were:

1) Difficulties with physical environment (crowding / hygiene): 205(40%)

2) Lack of equipment or supplies: 142(28%)

3) Problems with the availability or supervision of human resources (mainly nursing): 112(22%)

4) Inadequate distribution of patients or coordination of care: 99(19%)

5) Deficit in referrals or late consults: 55(11%).

SIBEN neonatal network: Data were obtained for 3,347 infants admitted to NICU in 2019, 1,644 in the first semester and 1,703 in the second one. We divided them in premature infants’ ≤1500 g and/or <34 weeks of gestation and infants> 1500 g and> 33 weeks. The most relevant data are presented below:

a) Mortality: the mortality rate for the 1,644 NB admitted to the units during the first semester of 2019 was 22.1% and fell to 19% during the second semester (n 1,703 RN); 39 fewer infants died (RR 0.86; 95% CI 0.75 to 0.98) with a significant risk difference between both semesters (-3.1%). In the subgroup of infants <1500 g, 34 fewer children died and mortality for this group decreased from 38.3% to 34% (RR 0.89 95% CI 0.76-1.04).

b) Prenatal corticosteroids (PC): the use of PC was reported in only 55% of pregnant women with preterm labor, although 87% of them had prenatal care. These data coincide with the findings described in RCA and indicate the need to optimize this indication through education and/or change in procedures.

c) Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA): a gradual increase was observed in the detection of PDA in NB ≤1500g, from total absence during the first semester of 2019 to a frequency of 7.2% DAP in the first trimester and 12.3% in the second trimester of the second semester of 2019. Although this frequency remains low for NB <1500 grams, detection is gradually increasing.

d) Pulmonary hemorrhage (PH): It was the most frequent cause of death. Fortunately its prevalence decreased from 7.5% in the first semester to 5.5% in the second semester of 2019; a significant decrease with relative risk reduction of 26% (RR 0.74 95% CI 0.57-0.96).

Cost analysis

A detailed cost analysis is pending. The preliminary information shows that the whole process was cost effective. The total cost for travel and lodging for 5 trips of 5 days duration each, with 3-6 educators from SIBEN (MD’s and RN’s) each trip was $57,000. Salaries for newly hired professionals for NICU’s were $280,000 and the cost for new equipment was $350,000, not including donations made by SIBEN. The total cost of the program was 687,000 US dollars. This represents 1,100 dollars per each of the 624 babies’ lives saved. With a life expectancy of about 70 years, the cost per year of life saved was less about 16 dollars, showing that the program was extremely cost effective.

Discussion

In the Dominican Republic, professional care for labor and delivery takes place in hospitals (98%). However, neonatal mortality rates are well above the average for the Latin American and Caribbean region [1,2]. Add to the local complexity that, according to data published by the United Nations, there are 567,648 immigrants, which represents 5.5% of its population. The main country of origin of immigration is Haiti (89%). In 2019, the number of immigrants living in the Dominican Republic has increased by more than 33%. This migratory phenomenon has clearly had an impact on birth rates and therefore on neonatal health [25].

Designing, implementing and measuring interventions aimed at reducing the death of newborns require multiple efforts, strategies and concrete actions to modify reality [26-28]. SIBEN and the NHS took up the challenge in October 2018 to try to improve the direct care of NB at risk of dying. The fundamental pillar of the plan was education, commitment and collaborative actions. In this document we present in detail the various actions that were developed throughout the first year.

In 2019, 8,811 more children were born than in 2018 and 624 fewer died. The significant relative reduction in the risk of dying was 26.3% (Table 1). The mortality of NB in the most important units also decreased significantly, the frequency of PH began to decrease and the diagnosis of PDA increased.

SIBEN has based its interventions on the premises of education and the need to have valid data, transformed into information to act in order to improve the care of the sick NB. The results obtained confirm that so far this has been successful for many children in the Dominican Republic. Even though a detailed cost analysis is pending, the preliminary information suggests that the process was fairly inexpensive, at less than 300,000 dollars, including equipment and salaries. If one relates this figure to lives saved or, more notably, to the number of years of life saved, the program was extremely cost effective.

A varied number of publications describe the impact of community interventions, but many were conducted in low-income countries in Asia and Africa where almost two-thirds of births occur at home [10], very different to the situation in Dominican Republic. There are also reviews that have measured the effect of single or combined interventions aimed at improving prenatal care coverage [11]. These publications do not reflect the situation in Latin American countries, where the majority of mothers have prenatal care and where neonatal births and deaths occur in health institutions, as it occurs in the Dominican Republic [1,2], where the deaths of newborns depend, to a large extent, on the quality of care delivered in health institutions. When the development of neonatal intensive care units is disorderly, with insufficient equipment and with little trained human resources, it is impossible to establish good care according to the needs of each sick NB [29].

The NHS and the Ministry of Health have also requested collaboration and alliances with different organizations other than SIBEN, to cover other topics to improve maternal and infant survival, such as health promotion, primary care and strategic coordination [30,31]. One year after the SIBEN-NHS agreement, better care in public hospitals has led to improvement of the survival of newborns and in the last year there have been 624 fewer deaths of NB in the Public Network of Health Services.

The main characteristics of the interventions implemented were related to a strong imprint on field work that integrated local MD’s and RN’s. The educational activities were based on training local professionals to transfer into action direct care improvement tools and on strategies to collect their own data, through the SIBENRCA and Neonatal Network. The training of nurses and neonatology residents has been a key element to ensure the continuity of the improvement found.

It is not possible to define clearly which one or more of the actions were the most effective, since it is not possible to disaggregate them, as they function as simultaneous components constantly adapted to the findings. This iterative, phased approach, which takes advantage of qualitative and quantitative methods, leads to a better design, execution and generalization of the actions implemented and improve the results [26]. In this way, SIBEN planned and carried its plan in the “real world” or in routine practice, paying special attention to the context and to local factors that influence poor results, but which are likely to improve. The results of the implementation included acceptability, adoption, adequacy, feasibility, fidelity, cost of implementation, coverage, and sustainability [27,28].

Much of the success of this first year is based on the joint and collaborative decision from the very beginning, identifying together with Dominican professionals the possible actions for improvement to be implemented quickly for the benefit of many NB. We proceeded with a systematic collection and evaluation of past and present conditions, together with political, social, and technological data, aimed at:

(1) Identification of internal and external forces that may influence the performance and choice of strategies, and (2) assessment of current and future strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

Many aspects still need to be improved. For example: decrease the unnecessary use of antibiotics and other ineffective treatments and/or with risk of short and long-term adverse effects, decrease the number of caesarean sections without precise indication, increase the use of prenatal steroids, train to provide care in delivery and resuscitation rooms 24 hours per day, infection control and promotion of efficient and effective neonatal leadership. The continuity of the collaboration project is essential to continue correcting errors and to consolidate changes adapted to the country’s health reality.

Achieving equitable, universal and supportive health systems may one day cease to be a utopia in developing nations. John F Kennedy said in the 1960s “... the quality of a country is measured by the way it treats its weakest and most dependent citizens: children ...” Almost 60 years later, justice has not yet been done for the neonatal population in Latin America. However, there are success stories like the one in the Dominican Republic that are stimulating and renew the strength of continuing to educate.

Conclusion

A significant increase in neonatal survival was achieved in the Dominican Republic, with a decrease in the neonatal mortality rate from 17‰ live births to 12.1‰, a risk reduction in neonatal mortality of 26%. This was due to education and to definite improvements in the provision of neonatal intensive care, in a costeffective manner.

Acknowledgement

To the entire SIBEN working group and to Dr Taina Malena for her vision and support. To María del Carmen Fontal RN, Aldana Ávila RN and to all MD’s and RN’s who care for sick newborns in Hospitals of the Dominican Republic. Among them: Dagne Sánchez, Candelaria Núñez, Yolanda Grullón, Jackeline Mojica, Nadia Rosario, Lourdes Peña, Leonora Despósito, Odrys Tejera, María Dolores Alcántara, Narda De Oleo, Juana Mena, Andrea Salas,Andrés Manzueta, Lizabeta Mamolar, Luzneida Hidalgo, Angela Suarez, Johana Gómez, Alejandra Vásquez, Rosa Maria Gómez, Milagros Núñez, and many many others.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- General Directorate of Epidemiology. Ministry of Public Health. http//digepisalud.gob.do (Downloaded March 2, 2020).

- National Alliance to Accelerate the Reduction of Maternal and Child Mortality - Framework Document. Ministry of Health, May 2019. https://www.msp.gob.do ›documents_oai› mispas-daf-cm2019. (Downloaded March 2, 2020)

- Cardetti, M Cedano, H Henriquez, M Tejera (2019) Births by cesarean section in the Dominican Republic: prevalence, indications and associated morbidity and mortality. Proceedings of the Summary of the XVI SIBEN Congress 2019, Quito, Ecuador.

- Data bases and information from Maternidad Alta Gracia and Hospital Estrella Ureña, Dominican Republic. October, 2018.

- Sola A (2004) Ibero-American Society of Neonatology. Collaborative group for the improvement of clinical practice and research in neonatology. An Pediatr (Barc) 61(5): 390-392.

- Sola A, Fariña D, Mir R (2016) VI SIBEN Clinical Consensus: Early detection of diseases associated with neonatal hypoxemia through the use of pulse oximetry. EDISIBEN, Paraguay, 978-1-5323-0369-2.

- Golombek S, Sola A, Baquero H, Cabanas F, Fajardo C, et al. (2008) First SIBEN clinical consensus: diagnostic and therapeutic approach to patent ductus arteriosus in premature newborns. An Pediatr (Barc) 69(5): 454-481.

- Sola A, Golombek (2017) Caring for Newborns in the SIBEN Way. EDISIBEN, Santa Cruz, Bolivia, September 2017 ISBN 6799578379746.

- Sola Augusto (2017) What do families of Sick Newborns teach us? EDISIBEN ISBN 9781532334535.

- Lassi ZS, Bhutta ZA (2015) Community-based intervention packages for reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality and improving neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD007754.

- Mbuagbaw L, Medley N, Darzi AJ, Richardson M, Habiba Garga K, et al. (2015) Health system and community level interventions for improving antenatal care coverage and health outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12): 1-157.

- Quality improvement program. Guides and instruments to assess the quality of care. Secretary of State for Public Health and Social Assistance Pan American Health Organization. https://paho.org (downloaded February 24, 2020)

- Daelmans B, Darmstadt GL, Lombardi J, Black MM, Britto PR, et al. (2017) Early childhood development: the foundation of sustainable development. Lancet Early Childhood Development Series Steering Committee. Lancet 389(10064): 9-11.

- Britto PR, Lye SJ, Proulx K, Yousafzai AK, Matthews SG, et al. (2017) Early Childhood Development Interventions Review Group. Nurturing care: promoting early childhood development. Lancet 389(10064): 91-102.

- Richter LM, Daelmans B, Lombardi J, Heymann J, Boo FL,et al. (2017) Investing in the foundation of sustainable development: pathways to scale up for early childhood development. Lancet 389(10064): 103-118.

- Lake A (2017) The first 1,000 days: a singular window of opportunity. https://blogs.unicef.org/blog/first-1000-days-singular-opportunity/

- Dua T, Tomlinson M, Tablante E, Britto P, Yousfzai A, et al. (2016) Global research priorities to accelerate early child development in the sustainable development era. Lancet 4(12): e887-e889.

- Horbar JD, Rogowski J, Plsek PE, Delmore P, Edwards WH, et al. (2001) Collaborative Quality Improvement for Neonatal Intensive Care. NIC/Q Project Investigators of the Vermont Oxford Network. Pediatrics 107(1): 14-22.

- Doyle LW (2006) Evaluation of neonatal intensive care for extremely-low-birth-weight infants. Seminars Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 11(2): 139-145.

- Boyer MM (2001) Root cause analysis in perinatal care: health care professionals creating safer health care systems. J Perinat Neonat Nurs 15(1): 40-54.

- Fariña D, Rodríguez S (2012) Root Cause Analysis of the factors linked to the death of newborns in public maternity hospitals in Argentina. Root Cause Analysis of factors related to the death of newborns hospitalized in public maternities in Argentina. Argent Public Health Magazine 1(3): 13-17.

- Sola A, Dominguez Dieppa F, Rogido MR (2007) An evident view of evidence-based practice in perinatal medicine: absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. J Pediatr (Rio J) 83(5): 395-414.

- Sola Augusto (2011) Neonatal care: Discovering the life of a newborn. ISBN: 9789872530341. Editorial Edimed, Argentina.

- María Teresa Montes Bueno, Ana Quiroga, Susana Rodríguez, Augusto Sola (2016) Family access to Neonatal Intensive Care Units in Latin America: A reality to improve. An Pediatr (Barc) 85: 95-101.

- Dominican Republic - Immigration 2019 | datosmacro.com. Available at https://datosmacro.expansion.com ›immigration› republica-dominicana (accessed March 3, 2020)

- Michelle Campbell, Ray Fitzpatrick, Andrew Haines, Ann Louise Kinmonth, Peter Sandercock, et al. (2000) Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ 321: 694-696.

- David H Peters, Taghreed Adam, Olakunle Alonge, Irene Akua Agyepong, Nhan Tran (2013) Implementation research: what it is and how to do it. BMJ 347: f6753.

- David H Peters, Nhan T Tran, Taghreed Adam Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization (2013) Implementation research in health: a practical guide.

- Speranza AM, Kurlat I (2011) Regionalization of perinatal care: a strategy to decrease infant mortality and maternal mortality. Rev Argent Public Health 2(7): 40-42.

- UNICEF (2017) The State of the World's Children 2016. An opportunity for every child. At https: /www.unicef.org/spanish/publications/files/ UNICEF_ SOWC_2016_ Spanish.pdf

- National Alliance for the Accelerated Reduction of Maternal and Neonatal Death. https://www.msp.gob.do ›documents_oai› mispas-daf-cm-2019-0179 (downloadedMarch5, 2020)

-

Sola A, Cardetti M, Malena T, Montes Bueno MT, Rosa Chupany C, Rodriguez S. Neonatal Survival Improvement in Dominican Republic through effective Collaboration of the Iberoamerican Society of Neonatology (SIBEN). Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 2(2): 2020. GJPNC.MS.ID.000535.

Neonatal mortality, Dominican republic, Education, Neonatal health services, Newborns, Root cause analysis, Neonatal care

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.