Case Report

Case Report

Neonatal Metabolic Acidosis after Intrauterine Exposure to Acetazolamide

Marwa Mansour1, Samarth Shukla2* and Josef Cortez2

1Department of Pediatrics, University of Florida College of Medicine - Jacksonville, USA

2Division of Neonatology, University of Florida College of Medicine - Jacksonville, USA

Shukla, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Division of Neonatology, University of Florida College of Medicine - Jacksonville, 655 W 8th Street, Jacksonville, Florida, USA 32209.

Received Date: November 26, 2020; Published Date: December 08, 2020

Abstract

Background: Acetazolamide is a commonly used drug for intracranial hypertension. Teratogenic and metabolic effects of acetazolamide on a fetus have sparsely been reported. Here, we report a neonate presenting with hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis associated with maternal use of acetazolamide during pregnancy.

Case description: A term female infant was born to a mother with normal prenatal course. During pregnancy, the mother was treated with acetazolamide for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. She presented with hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis soon after birth and was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for further evaluation and management. The serum bicarbonate and serum chloride concentrations were 12 mmol/L and 110 mmol/L respectively with normal remaining laboratory parameters. No other cause for metabolic acidosis was identified. Infant was treated conservatively with intravenous fluids and laboratory studies normalized over the next 48 hours.

Conclusion: The safety of using acetazolamide during pregnancy is not well established. This case points to possible fetal metabolic side effects of in utero exposure to acetazolamide. Potential exposure to maternal medications should be considered while evaluating neonatal metabolic acidosis with normal physical examination.

Keywords:Acetazolamide; Teratogenicity; Neonatal metabolic acidosis

Abbreviations: IIH - idiopathic intracranial hypertension; GBS - group B streptococcus; NICU - neonatal intensive care unit; RTA - renal tubular acidosis

Introduction

Acetazolamide is the mainstay of medical therapy for idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH). Other approved indications for acetazolamide include glaucoma, congestive heart failure, and epilepsy [1]. The main mechanism of action of acetazolamide is reversible inhibition of the enzyme carbonic anhydrase resulting in reduced hydrogen ion (H+) secretion at the proximal renal tubules and an increased renal excretion of sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, and a relative increase in serum chloride concentration [1,2]. Increasing the renal loss of bicarbonate (HCO3) leads to metabolic acidosis.

Metabolic acidosis presenting at birth raises the possibility of a varied etiology including birth asphyxia, sepsis, congenital heart diseases, and cardiorespiratory failure. Due to grave prognoses associated with these conditions, infants with metabolic acidosis often undergo extensive evaluation to identify the underlying cause. Metabolic acidosis due to maternal intake of medications may be the underlying cause if evaluation for higher acuity diagnoses remains futile.

Here we describe a case of a newborn who presented with hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis at birth and underwent extensive evaluation and management ultimately identifying maternal intake of acetazolamide as the underlying cause.

Case Presentation

A female infant was born at 40 weeks’ gestation via spontaneous vaginal delivery to a twenty four year old gravida 2 mother with normal prenatal testing and adequate prenatal care. Maternal testing for Group B streptococcus (GBS) was negative. The mother had no significant obstetric complications during pregnancy. She had a history of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) that was treated with 2,250 mg of acetazolamide twice daily throughout pregnancy. She also had a history of bipolar depression, headaches and gastroesophageal reflux disease treated with duloxetine, fioricet (combination of acetaminophen, butalbital and caffeine) and ranitidine, respectively.

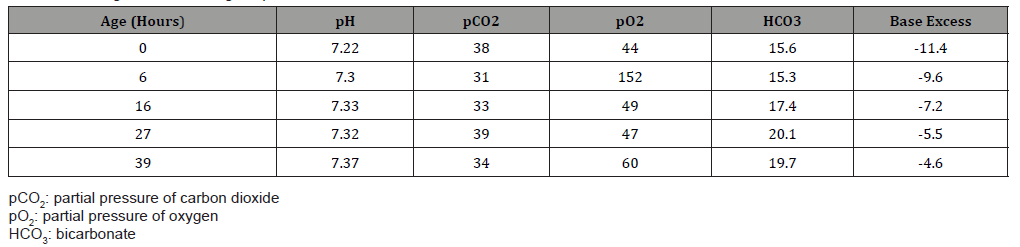

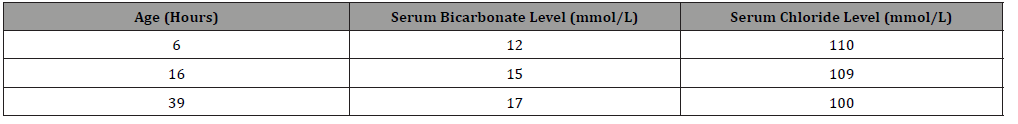

The perinatal course was unremarkable, but the infant had a cord blood gas, which was routinely obtained at our institution, showing metabolic acidosis: pH of 7.22 and base excess of -11.4 mmol/L (Table 1). There was no perinatal sentinel event suggestive of any hypoxic-ischemic processes, and the infant remained clinically well. An arterial blood gas obtained from the infant showed a base excess of -9.6 mmol/L. To confirm these findings, a basic metabolic profile (BMP) was sent that revealed serum bicarbonate concentration of 12 mmol/L (21-29 mmol/L) and serum chloride concentration of 110 mmol/L (101-110 mmol/L) (Table 2) with remaining electrolytes within normal range. For further evaluation of metabolic acidosis, infant was transferred to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU). In the NICU, complete blood cell count was normal with normal differential count. Blood glucoses ranged from 73-108 mg/dL (45-120 mg/dL) during first 24 hours.

Table 1:Blood gas results during hospital course.

Table 1:Serum bicarbonate and serum chloride concentrations during hospital course.

The infant was started on intravenous fluids containing sodium acetate, potassium acetate, and calcium gluconate. Feeds were avoided for first 24 hours while being evaluated for underlying cause. Laboratory studies were monitored frequently and showed gradually resolving metabolic acidosis with base excess improving to -4 mmol/L (Table 1), serum bicarbonate concentration improving to 17 mmol/L and serum chloride concentration improving to 100 mmol/L (Table 2) by third day of life. Since metabolic acidosis improved with conservative management, further evaluation was withheld. Infant’s physical exam continued to be normal. According to parental preference, the infant was started on formula feedings which were tolerated well and allowed the infant to be discharged home.

Discussion

According to the US Food and Drug Administration, acetazolamide is classified as a class C drug [3] indicating adverse effects on animal fetuses, but there are no well-controlled studies in humans. As a class C drug, acetazolamide should be prescribed only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. Acetazolamide is generally compatible with breastfeeding with very low rate of excretion into breast milk at high doses exceeding 1000 mg daily [4].

Teratogenic effects such as vertebral anomalies, gastroschisis, limb defects and dental anomalies have been reported with use of high doses of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors in animal species [5,6]. Nonetheless, studies in humans have shown inconclusive results. In an observational study of 101 women with IIH (total of 158 pregnancies), acetazolamide usage before 13 weeks of gestation was not associated with any major complications in the off springs [7]. The National Collaborative Perinatal Project reported no increase in major or minor fetal anomalies in the infants of 1024 women exposed to acetazolamide at different stages of pregnancy [8]. These studies, however, do not prove that acetazolamide is safe during pregnancy since the data is not able to exclude the teratogenic potential to cause rare birth defects. These potential rare defects have been described in incidental case reports.

Worsham et al reported a case of teratoma in the offspring of a patient treated with oral acetazolamide during the first 19 weeks of pregnancy [9]. Another report identified a twelve year old with ectrodactyly and syndactyly discovered at birth, while oligodontia of the permanent teeth was discovered at a later age [10].

Along with teratogenic potential, few case reports reported metabolic side effects of acetazolamide in newborns. For instance, a mother who was taking acetazolamide 250 mg orally twice daily delivered a preterm infant at 36 weeks of gestation. On second day of life, the infant developed electrolyte abnormalities consisting of hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, and metabolic acidosis [11]. Despite continued breastfeeding and maternal drug therapy, the infant’s metabolic acidosis disappeared on day 4 of life. The authors considered these metabolic effects to be caused by transplacental passage of acetazolamide.

Another case reported renal tubular acidosis (RTA) in a preterm boy shortly after birth. This infant’s mother had been treated for glaucoma with oral acetazolamide (750 mg/day) for three successive days before delivery. The infant developed hyperchloremic mixed respiratory-metabolic acidosis soon after birth. Acetazolamide was detected in his serum demonstrating transplacental acetazolamide passage [12].

In our case, the patient had no obvious congenital malformations. Infant had a benign prenatal and perinatal course and normal physical exam at birth. The infant presented with hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis that was promptly corrected after the cessation of exposure to acetazolamide. This potential adverse effect of acetazolamide during pregnancy should be carefully considered before embarking on extensive evaluation for neonatal metabolic acidosis, especially for an infant with no other risk factors and normal physical examination.

Conclusion

The safety of using acetazolamide during pregnancy is not well established. However, occasional case reports point to possible fetal teratogenic and metabolic side effects of transplacental acetazolamide. The current recommendation is to offer acetazolamide to mothers with high intracranial pressure or glaucoma, if benefits overweigh the risks. Informed consent and proper discussion with parents about the possible side effects should be considered. We report this case to encourage more research and reporting cases that may imply association between intrauterine acetazolamide and metabolic/ teratogenic side effects.

Acknowledgement

MM and JC were involved in patient care. MM, SS and JC conceptualized the report and prepared the manuscript. MM prepared the initial draft of manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Farzam K, Abdullah M (2020) Acetazolamide. StatPearls Publishing.

- Moviat M, Pickkers P, van der Voort PH, van der Hoeven JG (2006) Acetazolamide-mediated decrease in strong ion difference accounts for the correction of metabolic alkalosis in critically ill patients. Crit Care 10(1): R14.

- Meadows M (2001) Pregnancy and the drug dilemma. FDA Consum 35(3): 16-20.

- Söderman P, Hartvig P, Fagerlund C (1984) Acetazolamide excretion into human breast milk. Br J Clin Pharmacol 17(5): 599-600.

- Tellone CI, Baldwin JK, Sofia RD (1980) Teratogenic activity in the mouse after oral administration of acetazolamide. Drug Chem Toxicol 3(1): 83-98.

- Kojima N, Naya M, Makita T (1999) Effects of maternal acetazolamide treatment on body weights and incisor development of the fetal rat. J Vet Med Sci 61(2): 143-147.

- Falardeau J, Lobb BM, Golden S, Maxfield SD, Tanne E (2013) The use of acetazolamide during pregnancy in intracranial hypertension patients. J Neuroophthalmol 33(1): 9-12.

- Klebanoff MA (2009) The Collaborative Perinatal Project: a 50-year retrospective. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 23(1): 2-8.

- Worsham F, Beckman EN, Mitchell EH (1978) Sacrococcygeal teratoma in a neonate. Association with maternal use of acetazolamide. JAMA 240(3): 251-252.

- Al-Saleem AI, Al-Jobair AM (2016) Possible association between acetazolamide administration during pregnancy and multiple congenital malformations. Drug Des Devel Ther 10: 1471-1476.

- Merlob P, Litwin A, Mor N (1990) Possible association between acetazolamide administration during pregnancy and metabolic disorders in the newborn. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 35(1): 85-88.

- Ozawa H, Azuma E, Shindo K, Higashigawa M, Mukouhara R, et al. (2001) Transient renal tubular acidosis in a neonate following transplacental acetazolamide. Eur J Pediatr 160(5): 321-322.

-

Marwa Mansour, Samarth Shukla, Josef Cortez. Neonatal Metabolic Acidosis after Intrauterine Exposure to Acetazolamide. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 3(1): 2020. GJPNC.MS.ID.000554.

Acetazolamide, Teratogenicity, Neonatal metabolic acidosis, Intracranial hypertension, Infant, Drug, Neonatal intensive care unit, Serum bicarbonate

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.