Research Article

Research Article

Medical Emergencies in the Pediatric Service of the Lomé - Commune Regional Hospital Center (Togo)

Guédéhoussou T1, Agbéko F1, Djadou KE2, Hlomégbe MA1, Fiawoo M2, Azoumah KD3, Atakouma DY2 and Agbèrè AD1

1Pediatrics Unit, CHR - Lomé commune, Togo

2Pediatrics Unit, CHU-Sylvanus Olympio, Togo

3Pediatrics Unit, CHU Kara, Togo

Guédéhoussou Têtê, Paediatrics Unit, CHR - Lomé commune, Lomé, Togo.

Received Date: January 31, 2020; Published Date: February 18, 2020

Introduction

Any health worker who cares for children will be faced with medical emergencies. They are common and can start with alarming speed, but if treated quickly and effectively, it will have most of the time a positive result, or at least better than expected [1]. In sub-Saharan Africa, pediatric emergencies are often a matter of “disaster medicine” and several studies show the extreme gravity of the conditions seen in emergency consultations [2-5]. The mortality linked to these emergencies is significant: varying from 8% in Lomé in Togo to 14% in Ivory Coast [6,7]. The fight against child mortality must therefore go through a rapid diagnosis of pediatric emergencies and consequent treatment [8]. Thus, pediatric medical emergencies remain a daily reality, a real health problem and a concern with which all health personnel are confronted. In the Regional Hospital Center of Lomé - Commune (CHR-LC), being the youngest of the major reference hospitals in the city of Lomé, it was imperative, after six years of exercise, to establish the profile of the morbi - mortality of children consulting there, especially in a state of vital distress.

Materials and Method

Our study was carried out in the Paediatrics department of the Lomé-Commune regional hospital (CHR-LC). It is a secondary level hospital in the organization of the country’s health system, located in health district II of the Lomé - Commune region. This hospital was relocated in April 2010. Its Pediatrics department has 27 beds. This is a cross-sectional retrospective study. It covered the period from 1st January 2012 to 31st to Dec. 2017. The study focused on all records of children of both sexes of, under 15 years, received in the service in an emergency medical situation. We’re not included in the study patients presenting no threat to life and those with surgical emergencies. A pre-established and tested survey sheet was completed for each patient. The socio-demographic, clinical, paraclinical, therapeutic and evolutionary data were recorded. They were processed and analyzed using Epi Info 3.4.3 software. Pearson’s Chi-square test was used to compare the qualitative variables or the percentages, for a significance threshold p = 0.05.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

In total, 19,470 children were received in the consultation service during the study period. In all, 5,736 (29.5%) of these children were hospitalized, including 3,300 in an emergency department. These emergencies therefore represented 16.9% of consultations and 57.5% of hospitalizations. Two thousand and forty patients were included in the study. The M/F sex ratio was 1.4. The average age of our patients was 54.3 months (extremes 0 day and 180 months). Children under 5 years old accounted for 73.2% and 0 to 29 days 11.2% (Figure 1).

Clinical aspects

In total, 828 children (40.6%) were referred from public structures and private practices (16.8%) for pediatric emergencies. For many of them, there is no personal and family pathological history of the children in emergency conditions (88.6%), 02.8% were known to have sickle cell disease and 0.8% with a notion of atopy.

The main reasons for consultation were fever (90.0%), diarrhea (22.0%), prostration (19.4%), cough (15.3%), convulsions (13.5%), dyspnea (9.4%) and pallor (9.4%). Fever was only objectified at admission in 1020 children (60%), contrary to the parents’ complaints (fever in 90% of cases). One hundred and eight children (5.3%) had hypothermia at the entrance.

On examination, at least four in ten children (4 4%) was involved of the general state. Elsewhere, the main signs found were pallor (38.9%), pulmonary rales (22.8%), respiratory distress (18.4%) and dehydration (15.7%). The physical examination was normal in 8% of the cases. The main syndromes were established as follows: infectious syndrome (80.5%), deterioration in general condition (46.5%), anemic syndrome (40.1%), digestive disorders (33.2%), distress respiratory (17.2%) and dehydration (15.4%).

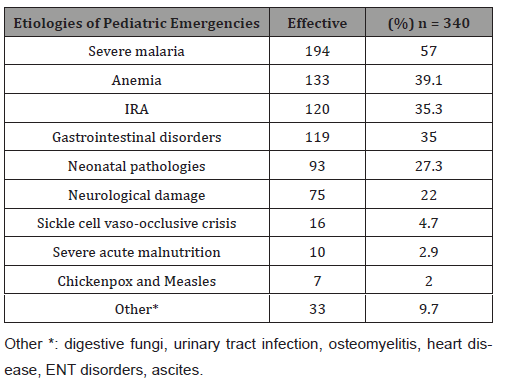

In our series, infectious emergencies represented nearly half of the types of emergencies (50.3%), followed by digestive emergencies and dehydration (18.2%), hematological emergencies (14.8%), neurological (10.5%), and (6.2%), Infectious and tropical pathologies constituted most of the causes of emergencies. Thus malaria (57.3%), anemia of nutritional or infectious origin (40%), acute respiratory infections (35.7%), gastrointestinal disorders (34.0%) and neonatal pathologies (27.3%) were the main etiologies. (Table 1).

Table 1:Distribution of children according to the etiologies of pediatric emergencies at CHR - Lomé Commune.

Analysis of paraclinical examinations

The average hemoglobin level found was 9.2 g/dl with extremes of 2.32g/dl and 18.22g/dl. With an overall achievement rate of 80.1, 56.1% of the children had hemoglobin below 10 g/dl. Among them, 33% had a rate below 8 g/dl. Regarding the white line, hyperleukocytosis was found in 56.1% of cases and leukopenia in 16%.

Thick blood smear was positive in 53.2% of cases. Of the 44.4% of patients in whom the thick blood smear was positive, the parasite density was greater than 1000 in 24.7%. The direct diagnostic test (RDT) alone confirmed the diagnosis of malaria in 3.2% of cases. The blood sugar level was performed in 45.9% of our patients on admission. At least one in six children had hypoglycemia (15.0%) and 2.7% had hyperglycemia.

Therapeutic and evolutionary aspect

A total of 43% (1,419) of our patients were resuscitated. Almost a third of patients (31.5%) were transfused and 28.4% were oxygenated. The most prescribed symptomatic treatments were based on the use of analgesics and antipyretics (85.2%), antianemics (76.2%), hypertonic glucose serum (45.2%), antiemetics (18. 9 %) and anticonvulsants (12.8 %). Most treatments were administered etiological the antimalarials (75.84 %), antibiotics (62.7 %) and antiparasitic (23.6 %).

If evolution was favorable in almost three- quarters of children (74.2%), 4, 5 % of patients died after admission. The average length of hospital stay was 4.0 days (range 1 and 29 days). The malaria severe anemic 39 /93 (41.9 %), the malaria severe neurological form 20/93 (21.5 %), the acute respiratory infections (ARI) 18/93 (19.4 %) and neonatal pathologies 16/93 (17.20 %) were the main causes of death.

Discussion

This study on pediatric medical emergencies during the first six years of this center since its creation, allowed us to identify the most frequent etiologies and to assess their management. Despite some constraints related to the lack of financial resources of the parents and of which most didn’t have a health insurance (74.2%) to conduct some paraclinical exams Paraclinical, we believe that our results are reliable.

Sociodemographic characteristics

The high frequency of pediatric emergencies (16.9% of consultation s and 57.5% of inpatients) especially common in lowresource countries. It is often linked to the delay of the decision of parents to go to consultation and sometimes problems ‘ accessibility referent care facilities it with respectively 90% and 30% [4,5,6,9]. The predominance of children under 5 is classic in proportions varying from 50 to 80% [2-4,7,8-10,13]. This high proportion is due to the vulnerability of low age children and complications of infectious and nutritional diseases. The fragility of this age group exposes it more to public health problems in our regions, thus requiring special attention to control programs [14].

Likewise, a male predominance has also been found in other studies in the African region and elsewhere with varying proportions varying suggesting the importance given more to the health of boys [3,5,11-13]. One in four emergencies were seen in the 4:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m. time slot, often in the afternoon or evening when parents return from work [4,10].s

Clinical aspects

In our study, fever (90%), diarrhea (22%), prostration (19.4%), cough (15.3%), convulsion (13.5%) and respiratory distress (9, 4%) were the first reasons for emergency consultations. It is the same dan s other studies in proportions ranging between of 59 % and 79% of [6.9 to 12.15]. This high rate of fever is justified by the fact that the infectious and tropical diseases represent affect dominant tions of our regions, often associated s to anemia, neurological disorders and dyspnea .

If the most observed syndromes were infectious syndrome (80%), deterioration in general condition (45.0%), anemic syndrome (39.9%), digestive disorders (30.3%), respiratory distress (16.5%) and dehydration (14.1%), they often determine the types of emergency . Thus, infectious emergencies represented 50.3% of the types of emergencies as in general in most tropical countries. In Europe, it is the neurological emergencies, ear, nose and throat, bronchopulmonary and serious ailments that prédomined [15].

The etiologies of medical emergencies were varied: malaria, anemia, ARI, gastrointestinal disorders and neonatal pathologies were the main causes of emergencies in 57.0%, 39.1%, 35.3%, respectively. 35.0% and 27.3% of cases corroborating with other studies [3,6] WHO reports [16]. In Europe, the types of emergencies seem to reflect the pathological panorama of the regions, their climates and their socio-economic conditions as well as the seasonal fluctuations (seasonal epidemics of bronchiolitis and gastroenteritis) Seasonal fluctuations [18].

Paraclinical aspects

The hard socio - economic conditions of our patients did not allow all the expected para - clinical examinations to be carried out. The hemoglobin level achieved for 56.1% of children was less than 10 g / dl, including a rate less than 6 g/dl in 18%. Anemias are very frequent in our communities and are more often the frequent consequences of the main infectious and nutritional pathologies, especially tropical, in children. Witness two former study s carried s in Togo and Benin [19,20]. who have shown that anemia is the most frequent manifestation of severe malaria in 49.18% and 49.1% of cases, respectively . Severe anemia therefore occupies an important place in children’s emergencies in tropical environments.

Thick blood smear remains an essential examination, as it was positive in 53.2% of cases for 57% of malaria cases diagnosed, the direct diagnostic test having confirmed the diagnosis of malaria alone in a very small proportion of children (3.2%). On the other hand, the blood sugar level was measured only in almost half of the children (45.9%). This can expose very many children to the serious consequences of hypoglycemia [21,22].

Therapeutic and evolutionary aspects

Con identifying resuscitation, 42.3% of patients had benefited. Among them, 29.7% were transfused. The unavailability of blood in emergency units would have several reasons: the fear of the donor population to find themselves HIV positive, the destruction of more and more blood tested HIV positive, the decline in voluntary and voluntary donors and the lack of resources parents of sick children to help acquire blood. Oxygen therapy was used in 27% of the cases and aspiration in 20.3%.

For symptomatic treatment, the analysis of emergency management reveals that the treatments instituted are not always adapted to the frequency of certain signs. It shows a strong use of antipyretics in 84.1% of cases, antianemics in 75%, antiemetics in 15.3% and anticonvulsants in 12.3%, although fever is not present in 60% of cases, anemia in almost 50% of cases, vomiting in 4.4% and convulsions in 13.5% of s cases.

For etiological treatment, antimalarials (72.9%), antibiotics (62.6%) and other antiparasitics (19.7%) were used more. There were more cases of malaria treated than diagnosed (72.9% vs 57%). In the CHU-Campus series [6], malaria was diagnosed in 29% of the cases while 92.4% of the children were receiving antimalarials. The main reasons were especially the endemicity of malaria in our environment which means that in the face of any fever, anti-malaria treatment is instituted almost systematically.

Regarding the Evolution aspect, the average hospital stay was 04 days. This duration is linked to the type of pathology received (infectious pathologies) whose treatment requires at least 3 days. The development was unfavorable in 4.5 % of cases against 8% at the CHU-Campus, where the most complex emergencies were referred [6]. Malaria anemias (4 1.9 %), neurological damage also linked to malaria (2 1.5 %), acute respiratory infections (ARI) (19.4 %), neonatal pathologies (17, 20%) were the main causes of death as found in the African literature [8, 16].

Conclusion

The main tropical pathologies including malaria, anemia, ARI, gastrointestinal diseases and neurological pathologies were the first emergency causes at CHR- Lomé Commune. In terms of treatment, blood transfusion remains a real problem, which can quickly affect the prognosis. The evolution was favorable without sequelae in 73.7%, the fatality rate of emergencies being 4.5% . Acute anemias, severe malaria, pneumonia, neonatal infections and neurological damage were the most lethal pathologies. It would be recommended to create a pediatric resuscitation unit in this hospital and to strengthen the technical platform and the skills of health professionals.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Molyneux EM, Quarm Goka B (2017) Paediatric emergencies in sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Emergency Medicine 7(Suppl): S1–S2.

- Devictor D (1994) Pediatric Emergencies: figures. In: Parisian Pediatrics Days Paris, Flammarion. Medicine-Science, pp. 381-386.

- Sylla Gueye M, Diouf S, Ndiaye O, Fall AL, Fall BF, et al. (2009) Pediatric emergencies in Dakar, Senegal. Risk factors for death. Med Afr Noire, pp. 495-500.

- Akodjènou J, Zounmènou E, Lokossou TC, Assouto P, Aguémon AR, et al. (2013) Pediatric emergencies of the pediatrics department of the Abomey – Calavi / Sô-Ava area hospital (BENIN): References and counter-references 18(1).

- Togola-Traore AO (2004) Emergency prescriptions in pediatrics at the C.H.U GABRIEL TOURÉ in Mali Doctoral thesis in pharmacy.

- Azoumah DK, Douti K, Matey K, Balaka B, Kessie K, et al. (2010) Pediatric medical emergencies at the CHU-Lomé Campus: Epidemiological aspects. J Rech Sci Univ Lomé (Togo) Serie D 12(2): 281-286.

- Asse KV, Plo KJ, Yao KC, Konaté I, Yenan JP (2012) Epidemiological, diagnostic, therapeutic and evolutionary profile of patients referred to the pediatric emergencies of the Bouaké teaching hospital (Ivory Coast). Rev Afr Anesth Med Urg Tome 17(3).

- Mirjam van Veen, Henriette A Moll (2009) Reliability and validity of triage systems in paediatric emergencycare. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine 17: (38).

- Lanetzki CS, Oliveira CAC, Bass LM, Abramovici S, Troster EJ (2012) The epidemiological profile of Pediatric Intensive Care Center at Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein. Einstein 10(1): 16-21.

- Ijaz N, Matthew Strehlow, Wang E, Pirrotta E, Tariq A, et al. (2018) Epidemiology of patients presenting to a pediatric emergency department in Karachi, Pakistan, BMC Emergency Medicine 18(1): 22.

- Atakouma DY, Gbetoglo D, Tursz A, Crost M, Agbèrè A (1999) Epidemiological study of the use of emergency hospital consultations among 5-year-old children in Togo. Rev Epidem And Public Health 47: 2S75-2S91.

- Tursz A, Crost M (1999) Epidemiological study of the use of care according to sex in children under 5 in developing countries. Rev Epidem and public health 47: 2S133-56.

- Darkaoui N, De Brouwere V, Zayyoun A, Filali H, Belouali R (1999) The use of an emergency hospital service for primary care (study at the Children's Hospital of Rabat, Morocco). Rev Epidem And Public Health 47(2): 2S53-64.

- (2016) WHO-MCEE Methods and data sources of child causes of death 2000-2015. Global Health Estimates Technical Papers WHO/HIS/IER/GHE 1.

- Mouyokani J, Tursz A, Crost M, Cook J, Nzingoula S (1999) An Epidemiological study of consultations with children under 5 years old in Brazzaville (Congo). Rev EPIDEM And Public Health 47: 2S115-2S131.

- Perret P, Gaze H, Kehtari R (1999) Pediatric emergencies: pre-hospital care. Medical Review of French-speaking Switzerland 119: 11-21.

- Pediatric emergencies within the emergency services of the Bordeaux University Hospital in 2010

- Grimprel E, Bégué P (2013) Pediatric emergency care in pediatric hospitals in France. Bull Acad Natle Med 197(6): 1127-1141.

- Assimadi JK, Gbadoe AD, Atakouma DY, Agbenowossi K, Lawson-Evi K, et al. (1998) Severe malaria in children in Togo. Arch Pediatr 5(12): 1310-1315.

- Ayivi B, Toukourou R, Gansey R (2000) Serious malaria in children at the CNHU in Cotonou. Le Bénin Médical 14: 146-152.

- JBE Elusiyan, Adejuyi EA, Ade OO (2005) Hypoglycaemia in a Nigerian Paediatric Emergency Ward. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 52(2): 96-102.

- (2015) Ministry of Health and Social Protection, Togo, DISER, Main health indicators in 2014.

-

Guédéhoussou T, Agbéko F, Djadou K, Hlomégbe M, Fiawoo M, et al. Medical Emergencies in the Pediatric Service of the Lomé - Commune Regional Hospital Center (Togo). Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 2(1): 2019. GJPNC.MS.ID.000528.

Outcomes, Neonatal, Transport, TRIPS, Nigeria, Neonates, Newborns, Morbidity, Mortality, Hospital, Hypoglycaemia, Pre-transport, Oxygen

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.