Case Report

Case Report

Isolated Benign Infantile Neutropenia

Othman Rizk A Mishref*

Department of Pediatrics - Neonatology, Ahmed Maher Teaching Hospital, Egypt

Othman Rizk A Mishref, Department of Pediatrics - Neonatology, Ahmed Maher Teaching Hospital, Egypt.

Received Date: November 17, 2020; Published Date: December 10, 2020

Abstract

Keywords:Neutropenia; Bone marrow failure; Severe combined immunodeficiency

History

A previously healthy, 10-month-old male infant presented with cold symptoms and fever (temperature up to 38.5 °c) for the last 3 days, that was responding to paracetamol for few hours then recurs. It was associated with slightly decreased oral intake. He is not irritable. He is breast feeding with little smashed food. There were no significant symptoms or signs other than fever. He had been doing well until his current illness.

• The bowel pattern and urination had been normal.

• No relevant past or family history or chronic illness or hematologic disorders.

• No previous hospital admission

• No history of contact with any specific infection

• perinatal history: full term, normal vaginal delivery, smooth perinatal history.

• Nutritional history: exclusive breast feeding till age of 6 months and then started weaning with smashed food, but mainly dependent on breast feeding.

• Vaccination history: vaccinated up to date.

• Normal developmental history

• Medication history: Nil.

Examination

Vital signs are normal. Height and weight are at the 50th percentile for age. Physical examination was normal. No; oral thrush, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin lesions are noted.

Routine investigations were done; complete blood count (CBC), C-Reactive Protein (CRP), Liver Function Tests (LFT), Renal Function Tests (RFT), all came normal except CBC showed marked neutropenia, absolute neutrophil count of 40/μL.

Clinical Course and Discussion

The patient was admitted for neutropenia workup. He was commenced on IV antibiotics (ceftazidime). He had undergone many laboratory tests without any clue to the diagnosis. These tests included a CBC, urine analysis, chest X-ray, blood culture, urine culture, stool culture, Widal test, Paul-Bunnell test, tests for brucellosis, leptospirosis, and dengue fever.

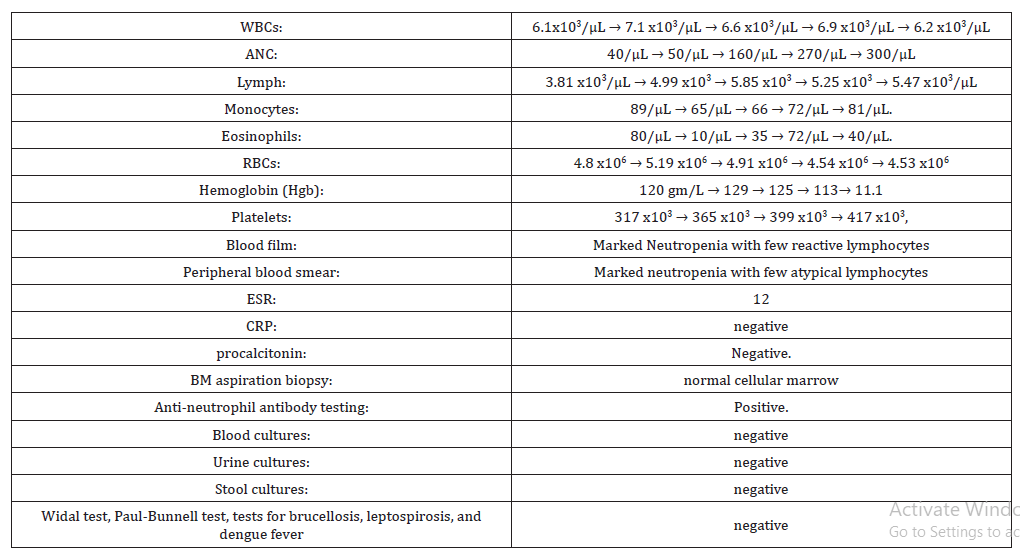

He had persistently low absolute neutrophil count (ANC) during hospital stay (Table 1):

Table 1:Laboratory results.

It is most unlikely that this infant has an acute bacterial infection, as fever has improved since admission and stayed afebrile till discharge from hospital, together with no focal site of infection or any complications, looks well, not toxic look, active and playing and feeding well. A chronic infection such as tuberculosis (TB) may present with continuous high fever, loss of weight, toxic look, night sweating as seen in disseminated/miliary TB. However, the patient received BCG vaccine and there is a BCG scar in the left shoulder. Other chronic infections without localizing symptoms include CMV, toxoplasmosis, malaria, EB virus, brucellosis are unlikely. Similarly, infiltrative disorders (malignancy/histiocytosis/sarcoidosis) are also a possibility

Of note, a CBC at birth demonstrated normal absolute neutrophil counts. There is no history of increased bacterial or fungal infections. He is the only child for the family and there is no family history of recurrent bacterial infection, neutropenia, immunodeficiency disease, autoimmune disease, or malignancy. There is no history of infant deaths in the family and CBC was done for both mother and father and was found to be normal. There has been no history of recent medication use. His growth and development had been normal until the onset of this illness.

The patient was discharged after 12 days. During his hospital stay he does well. During subsequent febrile illnesses, he does well clinically. Three months later, after he initially presented with neutropenia, his ANC improves to 1700 /μL. All investigations came normal except persistent neutropenia, positive Antineutrophil antibody, and diagnosis of chronic benign neutropenia of infancy and childhood is done.

Final Diagnosis

Chronic benign neutropenia of infancy and childhood.

Background

Neutropenia is defined as a decrease in the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) <1,500/ μL. ANC= (%bands + %mature neutrophils) X total WBC count. Neutropenia may be due to decreased neutrophil production, storage, or release; redistribution from circulating to marginated pools; or increased destruction. Neutropenia can be classified to; mild (ANC 1,000-1,500/μL), moderate (ANC 500- 1,000/μL), or severe (ANC <500/μL). ANC <200 is also termed agranulocytosis [1].

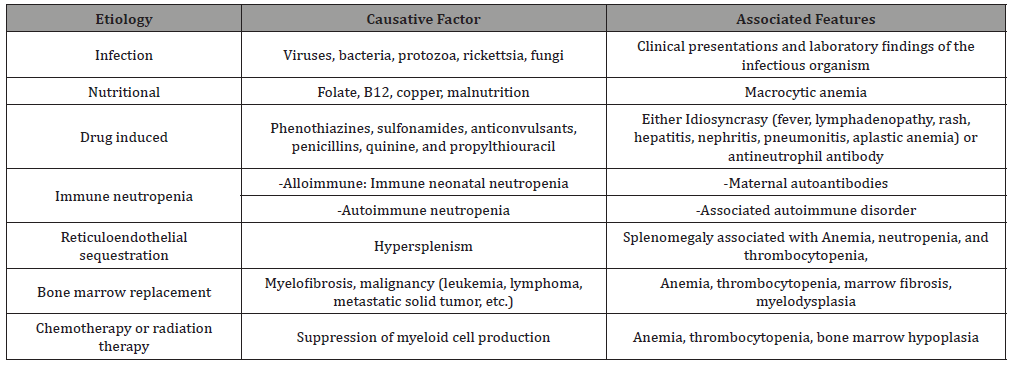

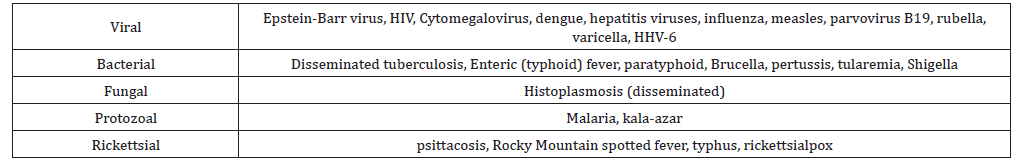

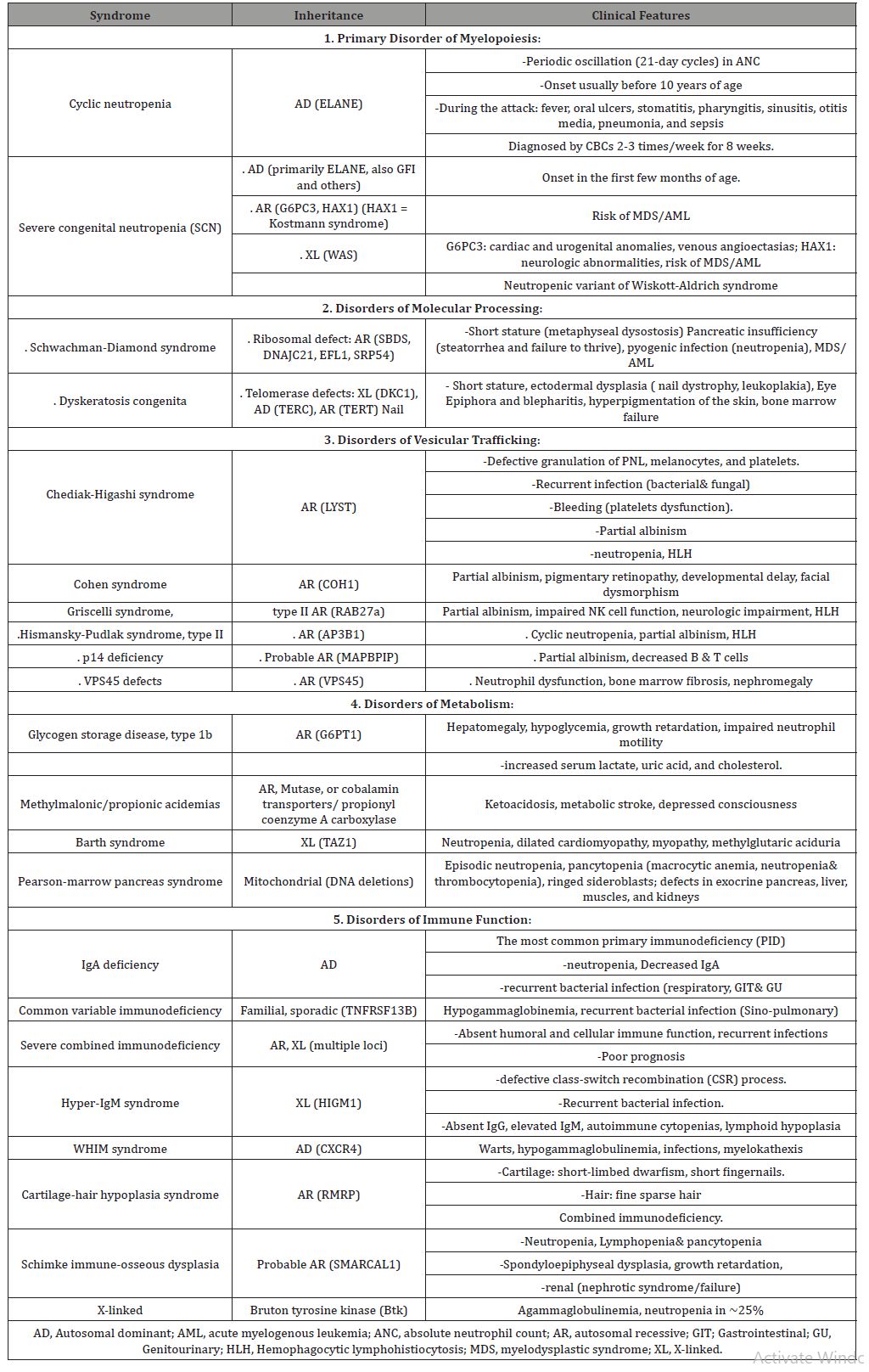

Acute neutropenia evolves over a few days because of rapid neutrophil consumption and compromised neutrophil production. Chronic neutropenia lasts longer than 3 months and arises from reduced production, increased destruction, or excessive splenic sequestration of neutrophils. The etiology of neutropenia can be classified as either an acquired, extrinsic disorders (Table 2&3) or more rarely an inherited, intrinsic defect (Table 4). Cyclic neutropenia is a rare (1-2/million) Autosomal Dominant (AD) disorder characterized by primary cyclic (every 21 days) variations in bone marrow reserve; regularly recurring fever every 21 days with oropharyngeal and skin infections. In general, common disorders are usually benign clinically and occur in children with no significant medical history of bacterial or fungal infections. Rare congenital disorders result in extremely high risks of infection and require specific laboratory tests to be diagnosed [2].

Table 2:Causes of Extrinsic Neutropenia.

Table 3:Infections associated with Neutropenia.

Table 4:Intrinsic (Congenital) Neutropenia.

When neutropenia is associated with infection it must be decided; whether, it is secondary to infection, or an underlying neutropenia contributed to the risk of infection. It is crucial to consider that the risk of infection with neutropenia is high when bone marrow production of neutrophils is decreased from either primary or secondary causes. Serious primary neutropenia or disorders of neutrophilic function are associated with “recurrent” or “atypical” bacterial infections. The most common clinical presentation includes fever, aphthous stomatitis, gingivitis, cellulitis, furunculosis, perianal inflammation, colitis, sinusitis, warts, and otitis media, as well as more serious infections such as pneumonia, deep tissue abscess, sepsis and fungal infection [3].

Chronic benign neutropenia of childhood represents a common group of disorders characterized by mild to moderate neutropenia that does not lead to an increased risk of pyogenic infections. Spontaneous remissions are often reported, although these may represent misdiagnosis of AIN of infancy, in which remissions often occur during childhood. Chronic benign neutropenia may be sporadic or AD or AR. Because of the relatively low risk of serious infection, patients usually do not require any therapy. Idiopathic chronic neutropenia is characterized by the onset of neutropenia after 2 yr of age, with no identifiable etiology. Patients with an ANC persistently <500/μL may have recurrent pyogenic infections involving the skin, mucous membranes, lungs, and lymph nodes. Bone marrow examination reveals variable patterns of myeloid formation with arrest generally occurring between the myelocyte and band forms. The diagnosis overlaps with chronic benign and Autoimmune neutropenia [4].

Consider genetic sequencing to identify mutations in genes associated with neutropenia. Mutations in ELANE are by far the most common cause of cyclic and congenital neutropenia. Use evidence of autosomal or recessive inheritance and clinical clues, i.e., cardiac, or urogenital abnormalities suggest G6PC3 mutation, malabsorption, short stature suggest Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, etc. Testing for a broad panel of genetic causes for neutropenia (HAX1, G6PC3, WAS, SBDS, etc.) are appropriate in children with no associated anomalies to guide testing or when a panel is less expensive than several individual tests [5].

The mainstays of care for a case of neutropenia are good hygiene, observation for early signs of infection and treatment with antibiotics when infections occur. Management depends on the main etiology and either it is acute or chronic neutropenia. Acquired transient neutropenia because of malignancies, immunosuppressive chemotherapy, infections usually are presented with fever, and sepsis is a major cause of death. Thus, early recognition and prompt aggressive treatment of infections may be lifesaving. Benign neutropenia with no evidence of repeated bacterial infections or chronic gingivitis usually requires no specific therapy [6]. Appropriate oral antibiotics may be sufficient for superficial infections in children with mild to moderate neutropenia. Subcutaneously administered G-CSF (Granulocyte- Colony Stimulating Factor) can provide effective treatment of severe chronic neutropenia, including SCN, cyclic neutropenia, and symptomatic chronic idiopathic neutropenias. Treatment leads to dramatic increases in neutrophil counts, resulting in marked improvement of infection and inflammation. Doses range from 2-5 μg/kg/day for cyclic, idiopathic, and autoimmune neutropenias, to 5-100 μg/kg/day for SCN. Long-term effects of G-CSF therapy include splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and rarely vasculitis; only patients with SCN are at risk for MDS/AML. Patients with SCN or SDS who develop MDS or AML respond only to HSCT; chemotherapy is ineffective. HSCT is also the treatment of choice for aplastic anemia or familial HLH [7-12].

Key Messages

• Patients with ANCs <500 and fever require prompt evaluation and the rapid initiation of broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics.

• Empiric parenteral antibiotic therapy (consider ceftazidime, vancomycin, or meropenem) to cover S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella species.

• Neutrophilic leukocytosis does not always indicate acute bacterial infection.

• Danger signs: failure to thrive, inflammatory anemia, thrombocytopenia, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, joint swelling/bone pain, dysmorphism, recurrent serious infections, fever/infectious symptoms every 21 days, unusual or resistant infections, periodontal disease. If any of these danger signs are present; patients should have more extensive evaluations and a hematology consultation. If no danger signs present; no further testing is needed, and parents should be reassured. The most likely diagnosis in the young child is chronic benign neutropenia.

• Routine use of G-CSF to increase bone marrow production of neutrophils is not indicated for most acquired neutropenia and should be limited to specific disorders where neutropenia is due to inadequacy of the marrow reserve pool.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Boxer LA (1996) Function of neutrophils and mononuclear phagocytes. In Bennett JC, Plum F, editors: Cecil textbook of internal medicine, ed 20, Philadelphia, Saunders.

- Fioredda F, Calvillo M, Bonanomi S, Coliva T, Tucci F, et al. (2011) Congenital and acquired neutropenia consensus guidelines on diagnosis from the Neutropenia Committee of the Marrow Failure Syndrome Group of the AIEOP (Associazione Italiana Emato-Oncologia Pediatrica). Pediatr Blood Cancer 57(1): 10-17.

- Sokolic R (2013) Neutropenia in primary immunodeficiency. Curr Opin Hematol 20(1): 55-65.

- Rezaei N, Moazzami K, Aghamohammadi A, Klein C (2009) Neutropenia and Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases. International Reviews of Immunology 28(5): 335-366.

- Makaryan V, Zeidler C, Bolyard AA, Skokowa J, Rodger E, et al. (2015) The diversity of mutations and clinical outcomes for ELANE-associated neutropenia. Curr Opin Hematol 22: 3-11.

- Peter E Newburgera, David C Daleb (2013) Evaluation and Management of Patients with Isolated Neutropenia, Semin Hematol 50(3): 198-206.

- Crawford J, Armitage J, Balducci L, Becker PS, Blayney DW, et al. (2013) Myeloid growth factors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 11(10): 1266-1290.

- Rosenberg PS, Zeidler C, Bolyard AA, Alter BP, Bonilla MA, et al. (2010) Stable long-term risk of leukaemia in patients with severe congenital neutropenia maintained on G-CSF therapy. Br J Haematol 150(2): 196-199.

- Dinauer MC, Lekstrom-Himes JA, Dale DC (2000) Inherited Neutrophil Disorders: Molecular Basis and New Thisapies. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program pp. 303-318.

- Husain EH, Mullah-Ali A, Al-Sharidah S, Azab AF, Adekile A (2012) Infectious etiologies of transient neutropenia in previously healthy children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 31(6): 575-577.

- Kyono W, Coates TC (2002) A practical approach to neutrophil disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am 49(5): 929-971.

- Kathleen E Sullivan (2019) Neutropenia as a sign of immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol 143(1): 96-100.

-

Othman Rizk A Mishref. A Case of Isolated Benign Infantile Neutropenia. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 3(1): 2020. GJPNC. MS.ID.000555.

Neutropenia, Bone marrow failure, Severe combined immunodeficiency, Autoimmune, Breast feeding, Bacterial infection, Anemia, Thrombocytopenia, Child, Illness, Fever, Malignancy

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.