Research Article

Research Article

Implementation and Evaluation of a Psychoactive Substance Use Intervention for Children in Afghanistan: Differences Between Girls and Boys at Treatment Entry and in Response to Treatment

Abdul Subor Momand1, Elizabeth Mattfeld2, Gilberto Gerra2, Brian Morales3, Thom Browne4, Manzoor UlHaq5, Kevin EO Grady6 and Hendrée E Jones*1,7

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, UNC Horizons, USA

2United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Austria

3Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL), US Department of State, USA

4Colombo Plan Secretariat, Sri Lanka

5United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Pakistan

6Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, USA

7Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins University, USA

Hendrée E Jones, PhD, UNC Horizons, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 410 N. Greensboro Street, Carrboro, NC 27510 USA.

Received Date: January 29, 2020; Published Date: February 07, 2020

Abstract

Psychoactive substance use among children in Afghanistan is an issue of concern. Somewhere around 300,000 children in the country have been exposed to opioids that either parents directly provided to them or by passive exposure. Evidence-based and culturally appropriate drug prevention and treatment programs are needed for children and families. The goals of this study were to: (1) examine lifetime psychoactive substance use in girls and boys at treatment entry; and (2) examine differential changes in substance use during and following treatment between girls and boys. Children ages 10-17 years old entering residential treatment were administered the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test for Youth (ASSIST-Y) at pre- and post-treatment, and at three-month follow-up. Residential treatment was 45 days for children and 180 days for adolescents and consisted of a comprehensive psychosocial intervention that included education, life skills, individual and group counseling and, for older adolescents, vocational skills such as embroidery and tailoring. Girls and boys were significantly different regarding lifetime use of five substances at treatment entry, with girls less likely than boys to have used tobacco, cannabis, stimulants, and alcohol, and girls more likely than boys to have used sedatives. Differences between boys and girls were found for past-three-month use of four substances at treatment entry, with girls entering treatment with higher past-three-month use of opioids and sedatives, and boys with higher past-three-month use of tobacco, cannabis, and alcohol. Change over the course of treatment showed a general decline for both girls and boys in the use of these substances. Girls and boys in Afghanistan come to treatment with different substance use histories and differences in past-three-month use. Treatment of children for substance use problems must be sensitive to possible differences between girls and boys in substance use history.

Keywords: Afghanistan; Boys; Girls; Opioids; Response to treatment; Substance Use; Treatment entry

Abbreviations: CHILD: Child Intervention for Living Drug-Free; WHO: World Health Organization; INL: International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, US Department of States; GLMM: General Linear Mixed Model; ASSIST: Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test; ASSIST-Y: Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test-Youth

Introduction

Afghanistan is one of only four countries in the world with the highest proportion of the population under the age of 15 years (48%). By comparison, adults in Afghanistan, ages 65 and older, represent only 3.7% of the population [1]. With a total fertility rate of 5.3 per woman [2], Having a ‘youth bulge’ creates an opportunity for economic development when youth are provided with an education and skills training; however, this ‘bulge’ can also be a threat as an insurgent group can readily attract uneducated youth for their purposes. Each year, 400,000 youth enter the Afghanistan job market and compete for economically rewarding jobs, which are very limited [3].

The farming, production, and easy accessibility of narcotics/ drugs are not only challenges for Afghanistan’s security and stability, but they are also a huge challenge for the health and wellbeing of the nation’s population, especially youth. For example, in one out of every three Afghan households there was person who tested positive for one or more types of psychoactive substances. Findings from the 2015 Afghanistan National Drug Use Survey [4] demonstrate that 11% of the population had positive test results for psychoactive substance use and 7.3% are currently using such substances; 12.8% of adults have used illicit psychoactive substances, double that of the global average (16% male and 9.5% female in the Afghanistan sample were using such substances)[5]. Regarding children, among those tested in Afghanistan, 9.2% tested positive for psychoactive substances, with 90% of them exposed through either their environment or given substances by their caregivers [4]. The use of multiple psychoactive substances early in life appears to lead to more problematic substance use disorders, as they increase the chance of affecting the developing brain [6]. The larger the number of adolescents and young adults exposed to experimenting with alcohol, tobacco, and illicit psychoactive substances, as well as controlled psychoactive medications, the greater the chances of these young people developing substance use disorders [7]. A biological testing survey conducted in in eleven provinces of Afghanistan [8], collected samples of saliva, urine, and hair from 5236 respondents. Findings showed that 11.4% household tested positive for any psychoactive substance, with opioids (5.6%) being the most prevalent, second was cannabinoids followed by benzodiazepines. Opioid use was common in women and children (more than 50%). After opioids, 31% of women tested positive for benzodiazepines and 24% children were test positive for cannabinoids. Thus, the population of children is clearly in need of treatment for substance use problems.

Children in Afghanistan are not only affected by substance use, but they have also been affected by war and traumatic events and family violence. For example, in a study that conducted interviews with a sample of children in Afghanistan, results show that 82.4% have experienced at least one event related to war due to ongoing conflict during their lifetime and nearly half (48.6%) reported at least one war-related event in the past year [9]. Further, children in Afghanistan reported exposure to 4.3 different types of violent events at home, 54.1% of children reported three or more types of events. One out of ten children have experienced an injury from beating at home. In contrast to the biological testing survey [8], this study demonstrated that substance use was not a considerable problem in children or in parents. A survey conducted [10] in Nangarhar province, Afghanistan revealed that exposure to different traumatic events was higher and 43.7% reported experiencing eight and ten traumatic events because of ongoing conflict. Among those interviewed 51.8% had symptoms of anxiety, 38.5% had symptoms of depression and 20.4 % had symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Mental health symptoms were more common in Women compare to in men. The study suggested that family and religion were helpful coping mechanism and serves as resources for emotional support. Another study that assessed the impact of an intervention called “CHILD” “Child Intervention for Living Drug-free ” shows that psychological and social problems were prevalent among children contacted by CHILD program and that the CHILD interventions had positive results for children who were at risk or using substances [11]. Children in Afghanistan face multiple challenges such as easy availability of substances, experiencing violence, trauma and life stresses. While our previous outcomes showed that the CHILD intervention had positive effects, possible gender effects were not previously examined in detail [11].

The goals of the study were to: (1) examine lifetime substance use in girls and boys at entry into substance use treatment centers established for women and children in Kabul, Herat, Balkh, Nangarhar, and Badakhshan provinces of Afghanistan; and (2) examine differential changes in substance use during and following treatment between girls and boys.

Materials and Methods

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval

Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board as well as the Ministry of Public Health of Afghanistan’s Institutional Review Board approved the project, the assent, consents, and data collection.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent or assent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardian(s). Aspects of consent included the aims of the project, the voluntary nature of participation, and that declining to participate at any time would not alter the ability to take part in residential treatment. Consent was read to the parent(s)/guardian(s). If the parent(s)/guardian(s) could not write, their thumbprint(s) were used to sign/stamp the consent. Assent was used when it was very difficult to obtain written consent based on the general cultural concerns regarding such a request and any full illiteracy issues encountered.

Participants

Participants were 396 children (57 girls, 339 boys) ages 10-18 years, of whom 1 girl and 1 boy were not assessed at baseline, and so did not have ASSIST-Y lifetime data. No additional demographic information was collected from the children as part of the CHILD intervention. More than half of childbirth deliveries take place at home in Afghanistan [2] and most children do not have a birth certificate or know their birth date; therefore, we asked children and their caregivers the child’s age by number of years. Regarding gender, Afghanistan is a conservative society and males and females still follow conventional roles; therefore, we used the term gender. During registration we asked males and females how they identified themselves regardless of their name or the traditional clothing they wore.

The data about the children reported in this paper is for the first 396 children who met the CHILD program. They were among the first of several thousand children who were subsequently screened by the program and had entered treatment. However, the number of girls in the sample (n=57) is substantially smaller than the number of boys (n=339). Data are unavailable regarding the relative substance use treatment needs of girls and boys or their relative prevalence in substance use treatment programs in Afghanistan. However, adult substance use prevalence in Afghanistan [4] estimated that 34% of adults using substances were women, suggesting that the number of girls in substance use treatment is likely to be lower than the number of boys, as has occurred in the present sample.

Behavioral intervention

The CHILD project has been implemented in five Afghanistan provinces: Kabul, Herat, Balkh, Nangarhar, and Badakhshan and the project provided substance use treatment services with three components: outreach, outpatient, and residential treatment centers. Detailed information about the interventions can be found in another article [11].

Measures

A battery of measures used in the CHILD project have been previously described [11]. Of relevance for this study is the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test-Youth (ASSIST-Y). ASSIST-Y is a screening tool developed for children ages 10-17 years old [12]. The ASSIST-Y was completed at preand post-treatment, and at three month follow-up. The ASSIST-Y represents a child version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) [13] developed under the World Health Organization (WHO) by an international group of substance use researchers to detect psychoactive substance use and related problems in primary care patients. The ASSIST-Y has 6 questions about each of 9 specific substance categories (tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, cannabis, cocaine, amphetaminetype stimulants, inhalants, sedatives, hallucinogens, opioids), as well as an “other” substance category. The first question asks about lifetime substance use and is scored 0 (‘no’) or 1 (‘yes’) for each substance category. A past-three-month substance involvement score for each of the substance categories is the sum of the responses to five questions for each substance category. (The exact questions and scoring principles can be found in the Note to Table 3) Substance involvement scores can range from a minimum of 0 to a maximum of 33. For tobacco products, alcoholic beverages, and inhalants, a score in the range of 2-5 is considered moderate risk, while a score of 6+ is considered high risk; for cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulants, sedatives, hallucinogens, opioids, and other substances, a score of 2+ is considered high risk. The ASSIST-Y has fair” internal consistencies” (0.62) and” test-retest reliability” was good (intraclass correlation coefficient is 0.63) with an optimal cutoff score of 2, yielding 73% sensitivity and 65% specificity [14].

Data collection and management

Participant assessments were collected on paper at the respective outreach, outpatient, and residential treatment centers and all project-supported facilities sent hard copies of the responses to the central data hub in Kabul, where data were checked and entered into a secure Microsoft Access database developed solely for this project.

Statistical analysis

Possible gender differences for lifetime substance use were tested with a generalized linear model (GLiM), in which the outcome variable was assumed to follow a binomial distribution. GLiM was chosen rather than logistic regression because it yields means scores for girls and boys, which are interpretable as a maximum likelihood estimate of the probability of lifetime use in each group.

A general linear mixed model (GLMM) framework was utilized to conduct the analysis of each of the ASSIST-Y substance involvement scores. Scores were assumed to follow a normal distribution in the population. There were three effects in the model: Gender as a fixed between-subjects factor, Time (residential intake vs. posttreatment vs. 90-day follow-up) as a fixed repeated factor, and their interaction.

A familywise error rate was used to test all effects, with α set to .0125 (.05/4), where the nominal Type I error rate was set at .05, and the family included the 4 ASSIST-Y past-three-month scales that were examined for change over time. Post hoc testing of simple mean differences associated with significant effects utilized the Dunn-Sidak multiple comparison test to control the post hoc testing error rate to at most the familywise error rate [15], which yielded a per comparison rate of .0042. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 [16].

Results

Since there was not enough variability for the analysis of the alcohol, cocaine, stimulants, inhalants, and hallucinogens, inferential tests for differences were not conducted. Tabular results for these five substances follow the presentation of results for tobacco, cannabis, sedatives, and opioids. A total of 89% of children in the sample reported use of tobacco in their lifetime as well as in the past three months. In the pre-treatment phase, the mean ASSIST-Y past-three-month total substance involvement score for tobacco for the sample was 17 (79% scored 12-25 indicating high risk, 6% scored 3 indicating moderate risk, and 17% scored 0-5 indicating low risk). A total of 54% of the sample reported cannabis use in their lifetime and 55% were at high risk for cannabis use disorder. A total of 6% of the sample reported using sedatives in their lifetime with an average score of 2.1, which means that they were at high risk and needed referral to treatment, and their pastthree- month mean score was 0.2. A total of 84% of the sample reported using opioids in their lifetime and their past-three-month mean score was 24 with 60% found to be at high risk for an opioid use disorder.

Gender differences in lifetime use for tobacco, cannabis, sedatives, and opioids

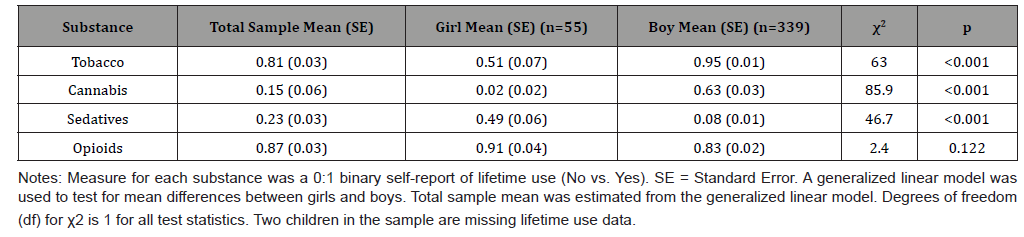

Table 1:Least Squares Means (Standard Errors) for Lifetime Substance Use in the Total Sample and Least Squares Means (Standard Errors) for Lifetime Substance Use, Tests of Significance, and p Values for Girls and Boys (N=394).

seen in Table 1, lifetime probability of tobacco and cannabis use was significantly higher among boys than girls, while lifetime probability of sedative use was significantly higher among girls than boys. Probability of lifetime tobacco use was almost double among boys than girls (Means: 0.95 vs. 0.51, respectively), while the probability of lifetime cannabis use was more than thirty times higher among boys than girls (Means: 0.63 vs. 0.02). In contrast, lifetime probability of sedative use was more than six-fold higher among girls than boys (Means: 0.49 vs. 0.08). Lifetime probability of opioid use did not differ between girls and boys, likely due to a ceiling effect; given the mean lifetime probability of opioid use in the total sample was 0.87.

Gender differences in past-three-month Substance Use for tobacco, cannabis, sedatives, and opioids

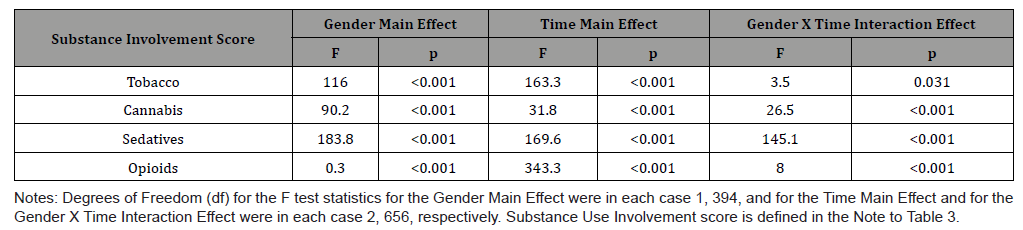

Table 2:Linear Mixed Model Tests of Significance and p Values for Main Effect for Gender, Main Effect for Time, and their Interaction for Past-threemonth Tobacco, Opioid, Cannabis, and Sedative Substance Involvement Scores (N=396).

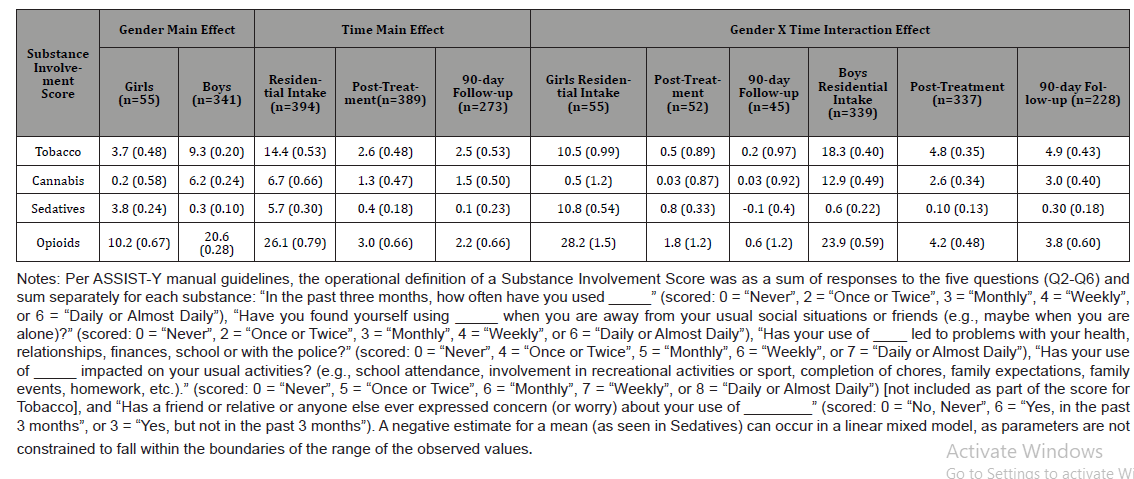

Table 3:Linear Mixed Model Least Squares Means (Standard Errors) for Gender Main Effect, Time Main Effect, and Gender X Time Interaction Effect for Past-threemonth Tobacco, Opioid, Cannabis, and Sedative Substance Involvement Scores (N=396).

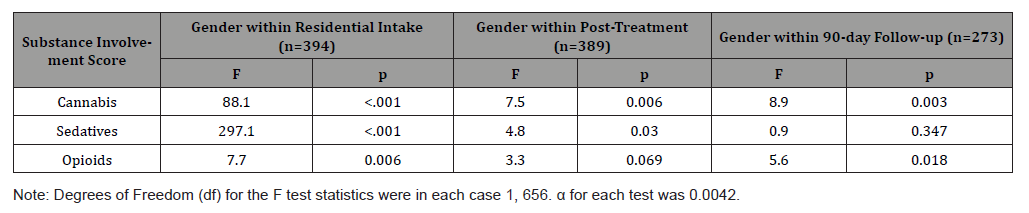

Table 4:Tests of Significance and p Values for Simple Main Effect of Gender within Time for the significant Gender X Time interaction effects for Pastthree- month Cannabis, Sedative, and Opioids Substance Involvement Scores (N=396).

Table 2 contains the results of the inferential tests for the Gender main effect, the Time main effect, and the Gender X Time interaction effect. Least squares mean substance involvement scores for the Gender, Time, and Gender X Time effects can be found in Table 3. Table 4 contains the tests of the simple main effects for Gender within each level of Time for the three significant Gender X Time interaction effects (cannabis, sedatives, and opioid substance involvement scores) as reported in Table 2.

As seen in Table 2, there were significant Gender X Time interaction effects for cannabis, sedatives, and opioid substance involvement scores, and significant Gender and Time main effects for tobacco substance involvement scores. [The significant Gender and Time main effects for cannabis, sedatives, and opioids are addressed in the post hoc testing for these three substances.]

Tests of the simple main effects for Gender within each level of Time for cannabis, sedatives, and opioid substance involvement scores indicated two significant simple main effects for Gender within Residential Intake, with the cannabis least squares mean for boys more than 25 times larger than the corresponding least squares mean for girls (Means: 12.9 vs. 0.5, respectively). Conversely, the sedatives least squares mean for girls was 18 times larger than for boys (Means: 10.8 vs. 0.6, respectively). The only significant Gender within three-month follow-up simple effect that reached significance was for cannabis, with the mean for boys 10 times larger than the mean for girls (Means: 3.0 vs. 0.3, respectively). It is notable that none of the three simple main effects for Gender within Time for opioids were significant. Examination of the least squares means suggested that the significant interaction arose because the decline in opioid use was more pronounced for girls than boys.

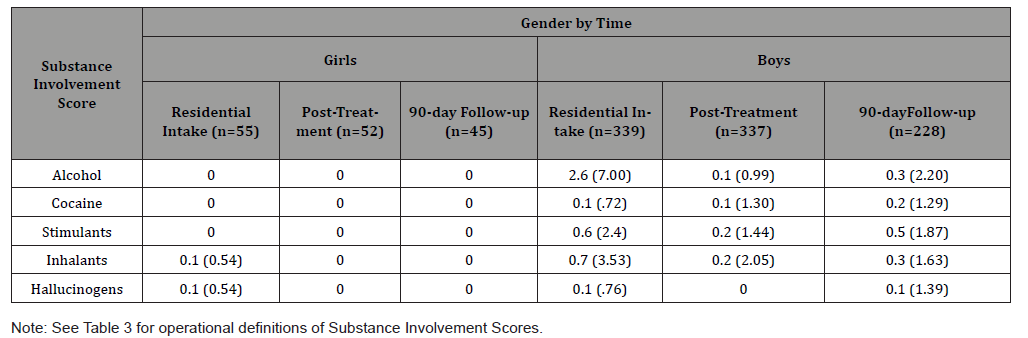

Table 5 shows that while boys reported very low levels of use of alcohol, cocaine, stimulants, inhalants, and hallucinogens, girls reported no use of any of these five substances, except for very low levels of inhalants and hallucinogens at residential intake.

Table 5:Means (Standard Deviations) for Gender by Time for Alcohol, Cocaine, Stimulants, Inhalants, and Hallucinogens Substance Involvement Scores (N=396).

Discussion

The twin goals of the present study were to: (1) examine lifetime substance use in girls and boys at treatment entry; and (2) examine differential changes in substance use during and following treatment for girls in comparison to boys. Girls and boys were significantly different on lifetime use of four substances at treatment entry, with girls less likely than boys to have used tobacco and cannabis, and girls more likely than boys to have used sedatives and opioids. During treatment, significant gender differences were found for four substances with boys entering treatment with higher past-three-month use of tobacco and cannabis, and girls with higher past-three-month use of opioids and sedatives. Change over the course of treatment showed a general decline for both genders in use of these substances. Findings suggest that girls reported higher lifetime use of sedatives and boys had higher lifetime use of tobacco and cannabis. In addition, boys were more likely to have used alcohol and stimulants in their lifetime. Past-three-month use of inhalants and hallucinogens in the pre-treatment phase were not significantly different between girls and boys, but boys were more likely than girls to have used these substances at post-treatment follow-up. This finding is comparable with other study findings in Afghanistan, namely that most women (69%) find it more socially acceptable to ingest rather than smoke substances. Swallowing a substance is associated with medicinal use and decreases the stigma associated with substance use [17]. These findings are also consistent with national prevalence figures in Afghanistan, where men more commonly use opioids and cannabis, while women more commonly use opioids and sedatives [4].

These findings also suggest that CHILD had a positive impact on reducing substance use in both girls and boys during residential treatment. The positive impact of the CHILD intervention must be seen in the context of a more general positive response to treatment impact rather than the specific impact of the CHILD intervention. This positive response of reduced substance use may be a result of being given the opportunity to live without exposure to psychoactive substances and to reside in a place that is physically and emotionally safe.

These results also speak to differences between girls’ and boys’ substance use experiences. It may be that the development of future interventions could benefit from being aware of the potential differences between boys and girls, and tailor discussions and activities around this reality. Understanding the context in which substance use is taking place (often inside the home for girls vs. both inside and outside the home for boys), and engaging caregivers in preventing substance access and use may be a continued key intervention point. Further, interventions for both girls and boys need to be focused on improving hope and optimism by leveraging the strength of Afghanistan’s cultural values such as faith, family unity, maintaining moral behavior, upholding honor, and serving society [18].

There were several limitations and two possible concerns that could be raised about the present study. One major limitation is that the CHILD protocol was designed to meet the treatment needs of children, based on a need’s assessment, and was not designed as a formal research study. Despite this limitation, analysis of the ASSIST-Y data shed light on the differential treatment needs of girls and boys in Afghanistan and the ability of the CHILD protocol to respond to their needs for treatment of substance use. A second limitation is that there are no data describing the children or their families, since recording such data was deemed not cost-effective to the project. Thus, it is not known how representative this sample of children is to other children in Afghanistan. Further, the project was necessarily a single-group study. It focused on change within a treated group, and there is neither a control nor a comparison group. However, the CHILD treatment protocol stemmed from treatment programs already in place in Afghanistan for children that had largely been unsuccessful in bringing about change in children’s behaviors. From this perspective, study findings suggest that the CHILD treatment shows promise for producing significant and enduring change in both girls and boys who need treatment for a variety of substance use problems.

The first concern that might be raised about this study is the disparate number of girls and boys that were assessed. However, as we noted above, this disparity may reflect the ‘real world’ prevalence of girls and boys in substance use treatment in Afghanistan. Certainly, this disparity did not adversely impact the power to detect any gender effect (a Gender main effect for either a lifetime use score or a past-three-month substance involvement score, or a Gender X Time interaction effect for the past-threemonth substance involvement score), as the only nonsignificant Gender main effect for lifetime use was for opioids, due to a ceiling effect for such exposure. The only Gender X Time interaction effect that failed to reach significance was for Tobacco, for which there was a significant Time main effect, suggesting a similar reduction in use over Time for both girls and boys. The second concern might be the assumption of a normal distribution for the ASSIST-Y scores. Given the multivariate nature of an outcome in a GLMM, assessing the assumption of a normal distribution for the residuals is complex. We did so using an iterative (with observations grouped by participant) influence analysis in which we examined both visually and graphically a variety of fit statistics, including but not limited to [19], the multivariate DFFITS statistic [20], and the covariance trace (COVTRACE) and covariance ratio (COVRATIO) statistics [21]. None of these statistics suggested any problem with modeldata agreement (and hence, no concerns with the assumption of a normal distribution for the outcome variables). For example, in any of the four analyses, the maximum values of COVTRACE was 0.86 and for COVRATIO, 1.08 (with the expected values for a solution with ‘no influence’ of 0 and 1, respectively).

Conclusion

Girls and boys in Afghanistan come to treatment with different substance use histories and differences in past-three-month use of tobacco, cannabis, sedatives, and opioids. Treatment for children who use substances must be sensitive to possible gender differences in use history.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Central Statistics Organization (2017) Afghanistan Living Conditions Survey 2016-17. Kabul, CSO, Afghanistan.

- Central Statistics Organization (CSO), Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), ICF (2017) Afghanistan Demographic and Health Survey 2015. Kabul, Central Statistics Organization, Afghanistan.

- UNFPA (2014) Afghanistan State of Youth Report 2014.

- SGI-GLOBAL (2016) Afghanistan National Drug Use Survey 2015.

- Ministry of Counter Narcotics (2015) Afghanistan Drug Report.

- Squeglia LM, Jacobus J, Tapert SF (2009) The Influence of Substance Use on Adolescent Brain Development. Clin EEG Neurosci 40(1): 31-38.

- Lubman DI, Yüce M, Hall WD (2007) Substance use and the adolescent brain: A toxic combination? J Psychopharmacol 21(8): 792-794.

- Cottler LB, Ajinkya S, Goldberger BA, Ghani MA, Martin DM, et al. (2014) Prevalence of drug and alcohol use in urban Afghanistan: epidemiological data from the Afghanistan National Urban Drug Use Study (ANUDUS). Lancet Glob Health 2(10): e592-e600.

- Catani C, Schauer E, Neuner F (2008) Beyond individual war trauma: Domestic violence against children in Afghanistan and Sri Lanka. J Marital Fam Ther 34(2): 165-176.

- Scholte WF, Olff M, Ventevogel P, De Vries GJ, Jansveld E, et al. (2004) Mental health symptoms following war and repression in eastern Afghanistan. JAMA 292(5): 585-593.

- Momand AS, Mattfeld E, Morales B, Haq MU, Browne T, et al. (2017) Implementation and Evaluation of an Intervention for Children in Afghanistan at Risk for Substance Use or Actively Using Psychoactive Substances. International journal of pediatrics.

- Humeniuk R, Holmwood C, Beshara M, Kambala A (2016) ASSIST-Y V1.0: First-Stage Development of the WHO Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and Linked Brief Intervention for Young People. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse 25(4): 1-7.

- Ali R, Meena S, Eastwood B, Richards I, Marsden J (2013) Ultra-rapid screening for substance-use disorders: The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST-Lite). Drug Alcohol Depend 132(1-2): 352-361.

- Kallmen H, Berman AH, Jayaram-Lindstrom N, Hammarberg A, Elgan TH (2019) Psychometric Properties of the AUDIT, AUDIT-C, CRAFFT and ASSIST-Y among Swedish Adolescents. Eur Addict Res 25(2): 68-77.

- Kirk RE (1979) Experimental-Design: Procedures for the Behavioral-Sciences. Current Contents/Social & Behavioral Sciences (45): 10-10.

- SAS Institute Inc (2011) The SAS System for Windows. Release 9.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute.

- Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (2008) Effective Factors Associated with Drug Addiction and the Consequences of Addiction among Afghan Women.

- Eggerman M, Panter-Brick C (2010) Suffering, hope, and entrapment: Resilience and cultural values in Afghanistan. Soc Sci Med 71(1): 71-83.

- Cook RD (1977) Detection of influential observation in linear regression. Technometrics 19(1): 15-18.

- Belsley DA, Kuh E, Welsch RE (1980) Regression Diagnostics; Identifying Influential Data and Sources of Collinearity. John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA.

- Christensen R, Pearson LM, Johnson W (1992) Case-deletion Diagnostics for Mixed Models. Technometrics 34(1): 38-45.

-

Abdul Subor M, Elizabeth M, Gilberto G, Brian M, Thom B, et al. Implementation and Evaluation of a Psychoactive Substance Use Intervention for Children in Afghanistan: Differences Between Girls and Boys at Treatment Entry and in Response to Treatment. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 2(1): 2019. GJPNC.MS.ID.000527.

Afghanistan, Boys, Girls, Opioids, Response to treatment, Substance Use, Treatment entry, Psychoactive Substance, Tobacco, Cannabis, Alcohol, Drug, Children.

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.