Research Article

Research Article

Immediate Outcomes of Neonatal Transport in a Tertiary Hospital in South-West of Nigeria

Tongo Olukemi1*, Abdulraheem Muhydeen A2, Orimadegun Adebola E3 and Akinbami Felix O4

1Department of pediatrics, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

2Department of pediatrics, University College Hospital Ibadan, Nigeria

3Institute of Child Health, University of Ibadan, Nigeria

4Department of pediatrics, Niger Delta University, Nigeria

Tongo Olukemi, Department of pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Nigeria.

Received Date: January 31, 2020; Published Date: February 18, 2020

Abstract

Aim: Only a third of deliveries in Nigeria occur in health facilities and a number of sick neonates have to be referred for advanced care. We sought to assess the morbidity and mortality within 24 and 48 hours of arrival among neonates presenting at the University College Hospital, (UCH) Ibadan in relation to the prevailing neonatal transport care practices.

Methods: The pretransport and intratransport care available to 401 neonates presenting in UCH were determined and their respiratory rate, heart rate, SpO2, serum bicarbonate, temperature and blood pressure were checked on arrival. TRIPS (Transport Risk Index of Physiologic Stability) scores were determined and same parameters were reassessed 24 and 48 hours after presentation.

Results: Nineteen babies (4.7%) were brought in dead. The morbidities present on admission were hypothermia (35.1%), hypoxia (28.4%), hypoglycaemia (12.5%), apnoea (9%), acidosis (8.2%), unrecordable blood pressure (16.5%). The median TRIP score on arrival was 17 with 23% having very severe score (>30), severe 19.4%, moderate 24.6% and low 33%. Babies who received oxygen, IVF/breastmilk during transport were more in the low and moderate scores. By 48 hours of admission, 22% had died and those who did not receive IVF/breastmilk had the highest risk of dying (OR 4.67 CI 1.81,12.05).

Conclusion: Neonates presenting at the UCH had significant morbidity and mortality in the first 48 hours of presentation, which was associated with poor pre and intratransport care. It is crucial to emphasize pretransport stabilization and suitable intratransport care in the training of peripheral healthcare workers in resource limited settings in order to improve newborn outcomes.

Keywords: Outcomes; Neonatal; Transport; TRIPS; Nigeria

Abbreviations: CHILD: Child Intervention for Living Drug-Free; WHO: World Health Organization; INL: International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, US Department of States; GLMM: General Linear Mixed Model; ASSIST: Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test; ASSIST-Y: Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test-Youth

Introduction

Neonatal morbidity and mortality continue to be major public health burden in developing countries despite the availability of proven cost-effective interventions for addressing it [1]. By the end of 2015, global neonatal mortality rates (NMR) had not reduced as much as under-five mortality rates and the need for 13 nations including Nigeria to accelerate the reduction in neonatal mortality rate in order to achieve 12 per 1000 live births by 2030 in line with the SDGs has been identified [2]. The need to strengthen community and facility newborn care services to achieve this cannot be overemphasized.

It has been shown that poor pre-transport and intra-transport care is associated with early neonatal morbidity and mortality [3]. Serious neonatal morbidity such as hypothermia, hyperthermia and hypoglycaemia may result from poor transportation and inadequate care resulting in increased risk of neonatal mortality [4,5]. Furthermore, only about 36% of births take place in health facilities in Nigeria [6], which implies that many of the neonates are delivered in settings without adequate resources for newborn care and they would require immediate transportation to betterequipped facilities should they require further care. Sick neonates in developing countries including Nigeria often require to be transported from places of birth to other health facilities for better care in conditions that are often suboptimal and capable of compromising survival even if they get to such centers alive [7]. The conditions of most transported neonates on arrival at the neonatal care centers can be poor because of inadequate attention given to pre- and intra-transport stabilization. Many of the babies thus transported are cold, blue, and hypoglycemic, and as many as 75% of the babies transferred this way have been reported to have serious clinical complications [8-10]. One of the critical requirements for neonatal referral is optimal transportation from the place of delivery to neonatal care centers, as well as the clinical state of the child being transported. In many developed countries, this aspect of neonatal care is well documented and there are established guidelines as well as written polices, but there is dearth of data on neonatal transportation and its immediate outcomes in Nigeria or other sub-Saharan countries. The only available data from Nigeria was published over 40 years ago, which may not be a true reflection of the current practice [11].

The TRIPS score has been used as a tool to evaluate the effect of transport on illness severity in newborns even in some developing countries [12]. The TRIPS score is not being used in Nigeria and many other developing countries however, it would be a useful tool in such settings as it would allow health care workers assess the impact of transport practices on outcomes of these sick newborns and make necessary adjustments. Although some information is available on the clinical state of referred and inborn neonates at point of admission in Nigeria [13-15], not much is known about the effect of transportation on these morbidity in the first few hours of admission. This study was conducted during a study to evaluate neonatal transport practices in Ibadan, South West Nigeria which has been previously published [7]. It sought to determine the association between pre-transport and intra-transport care and immediate (first 48 hours) morbidity using the TRIPS score and mortality of neonates presenting to UCH a tertiary hospital in South West Nigeria.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional study of newborns presenting at the emergency unit of the University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan from August 2012 to February 2013. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital ethics review committee. Newborns with lethal congenital anomalies such as anencephaly were excluded from the study. The UCH receives referral from other hospitals/clinics in Ibadan and neighboring villages, towns, and states. Newborns accounted for about 30% of the annual pediatric emergencies seen. The newborns were resuscitated and stabilized at the emergency unit, and subsequently transferred to neonatal wards within 48 hours of presentation.

Four hundred and one consecutive newborns out of 411 presenting to the children’s emergency room, UCH were recruited. Information on resuscitation and the care given before referral, during transport and on admission was obtained with a structured case record form. Resuscitation for this purpose was at least clearing of the airway usually by suctioning using manual suction, bulb syringe or suctioning machine and bag and mask ventilation if indicated.

On admission, detailed clinical assessment of each baby was carried out and the following parameters documented; the rectal temperature, random plasma glucose, respiratory rate, heart rate, oxygen saturation, blood pressure and serum bicarbonate. The Transport Risk Index of Physiologic Stability (TRIPS) score was calculated for each of the neonates and classified as low (0-10), moderate (11-20), severe (21-30), and very severe (>30) [16-19]. The TRIPS comprise four empirically weighted items (temperature, blood pressure, respiratory status, and response to noxious stimuli) is validated for infant transport assessment [20]. Each neonate was reassessed after 48 hours of presentation to determine the outcome in terms of normalization of above parameters and/or mortality. Mortality within 24 hours was also noted. All neonates that were brought in dead were also recruited and the pre- and intra-transport information were obtained.

The rectal temperatures were measured by the attending nurse using digital thermometers (Omron® Digital Thermometer, made in Germany). Oxygen saturation was recorded using the pulse oximeter (Massimo® Rad 5 Pulse Oximeter, made in U.S.A). The random plasma glucose was determined using the glucometer (Accu-Chek® Glucometer, made in Germany). The serum bicarbonate was also determined in the laboratory. All the above procedures were done following the written protocol in-use at the emergency unit during the study. The neonates were weighed using an infant digital weighing scale (SECA Model 354, SECA Medical Systems, made in Germany) to the nearest 10g. General examination was performed and standard protocol of care of newborns as practiced in the department was followed.

Hypothermia was defined as temperatures <36.5 °C (WHO) [20]. Hypoglycaemia was taken as blood glucose <2.2mmol/l, using American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendation [21], SpO2 values less than <90% was considered as hypoxaemia [22] and bicarbonate <16mmol/L as metabolic acidosis [23]. The expected pretransport care was as defined by STABLE, an acronym for “Sugar control, Temperature control, Airway maintenance, Blood pressure, Laboratory work, and Emotional support for the family” [24]. Emotional support could not be quantified, hence, for this study, emotional support was taken as all actions taken at the sources of referral or during transportation to ameliorate the emotional distress the caregivers were undergoing immediately the decision to refer the neonate was taken. It included empathy, counselling regarding explanation of the diagnosis and hope given to the caregivers of the patients from referring centers.

Data analysis

The main outcome (dependent) variables were the immediate morbidity on arrival in the emergency unit (core temperature, oxygen saturation, random plasma glucose, respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, resuscitation requirements as well as serum bicarbonate) and whether patient survived the first 24 hours and 48 hours or not. Independent variables were pre-transport and intratransport care given to neonates such intravenous fluid, oxygen administration, incubator care, administration of drugs, methods of resuscitation and means of providing warmth. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi square test while continuous variables were compared by the student t-test. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine predictors of survival for 48 hours. Only variables found to be significantly associated with outcome (survived or died) were included in the logistic regression model. The data were entered and analyzed using SPSS 17.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc. USA). Statistical significance level was set at P = 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants

A total of 401 neonates born to 379 mothers out of the 411 that presented during the study period were recruited into the study and the details of their socio-demographic characteristics, places and modes of delivery, sources of referral and means of transportation as well as the diagnoses have been previously described in an earlier publication [7].

Conditions of neonates on arrival in the children emergency ward

Of the 401 neonates, 19 (4.7%) were certified dead on arrival. There were no TRIPS scores available at the point of referral in all the cases. The following physiologic derangements were present on arrival: hypothermia (n = 135/382; 35.1%), hypoxaemia (n = 108/382; 28.4%), hypoglycaemia (48/382; 12.5%), apnoea (34/382; 9.0%), metabolic acidosis (31/382; 8.2%), and unrecordable systolic and diastolic blood pressure in 63 (16.5%) and 97 cases (25.4%), respectively. The TRIPS scores were 0 – 65 with a median of 17. However, about a quarter (23%) of the neonates had very severe scores (>30).

Diagnoses and outcomes at 48 hours

The provisional diagnosis of 382 neonates that survived till presentation included medical and surgical problems. By 48 hours, 22.0% of the neonates still had hypothermia, 2.5% had hypoxaemia, 3.7% had metabolic acidosis and only 0.2% had hypoglycaemia. Receiving any form of intra-transport care was not significantly associated with the morbidities recorded at 48 hours of admission. Fifty-seven (15%) of the neonates died within 24 hours of presentation while 13 (3.3%) died between 24 hours and 48 hours of presentation. These gave an in-hospital mortality rate of 15.0% (57/382) and 18.3% (70/382) at 24 hours and 48 hours, respectively.

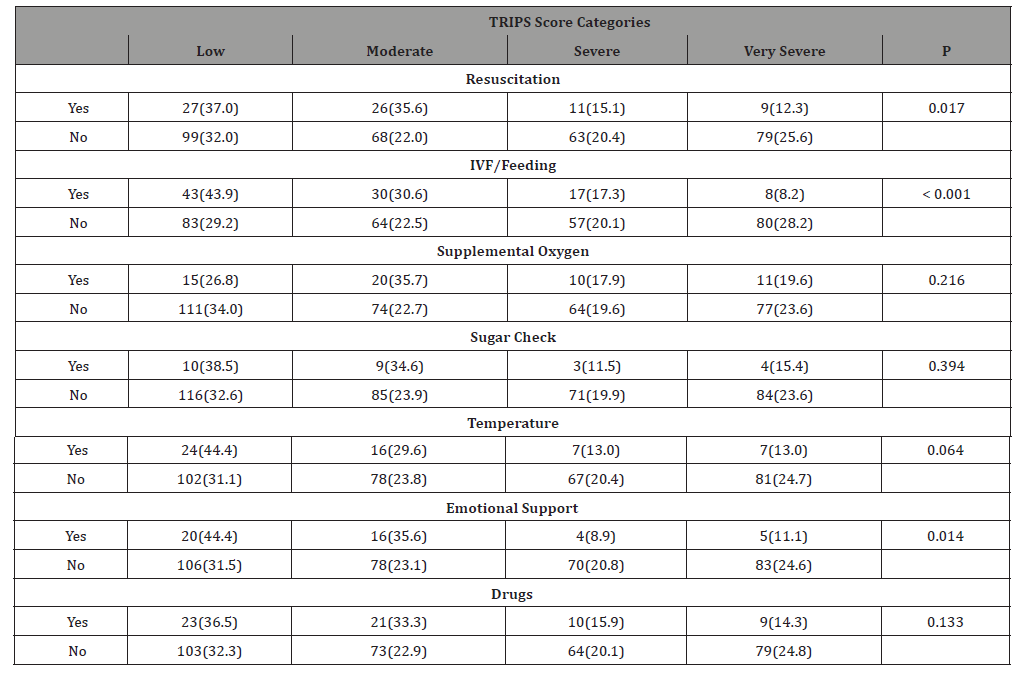

Association between TRIPS score and Pre-transport, Intra-transport care

The distribution of neonates according to TRIPS score category and pre-transport care received are as shown in Table 1. There were significant associations between TRIPS score category and each of resuscitation, intravenous fluid (IVF)/feeding and emotional support for the caregivers. Notably, low and moderate TRIPS scores were more frequently recorded among neonates who had resuscitation compared with those who did who did not receive resuscitation (Table 1). Similarly, neonates who did not receive IVF/feeding and emotional support from the caregivers were more in the severe and very severe TRIPS score categories than those who had these pre-transport care.

Table 1:Pre-transport care and TRIPS score of 382 neonates.

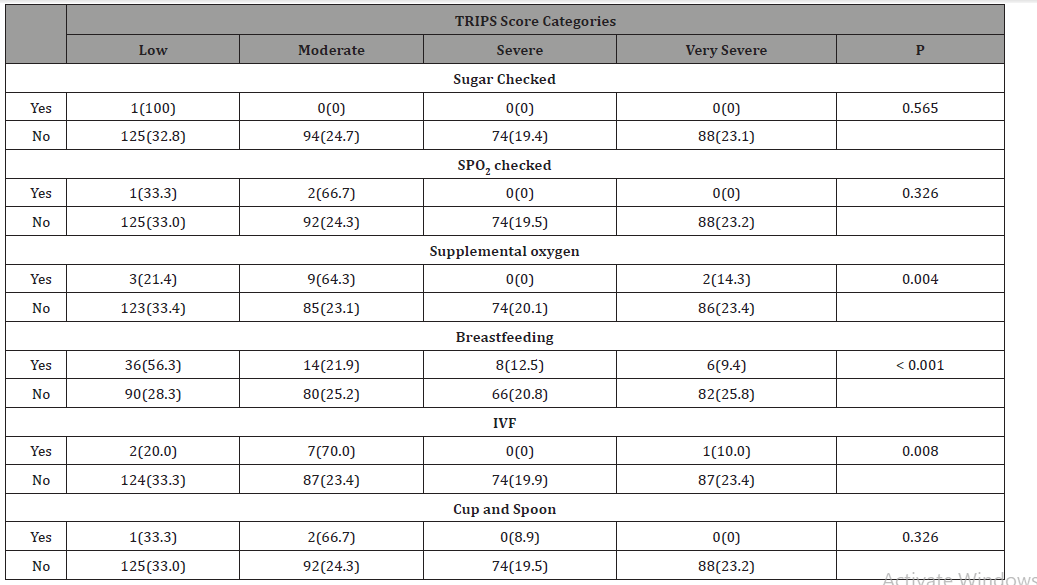

There were significant associations between TRIPS score category and supplemental oxygen, and IVF/breastfeeding during transport, more neonates who did not receive supplemental oxygen compared with those who received supplemental oxygen had severe (20.1% versus 0%) and very severe (23.4% versus 14.3%) TRIPS scores. Similarly, neonates who did not receive IVF or breastfeeding were significantly more in the severe and very severe TRIPS score categories than those who had these pre-transport cares as shown in Table 2.

Table 2:Intra-transport care and TRIPS score of 382 neonates.

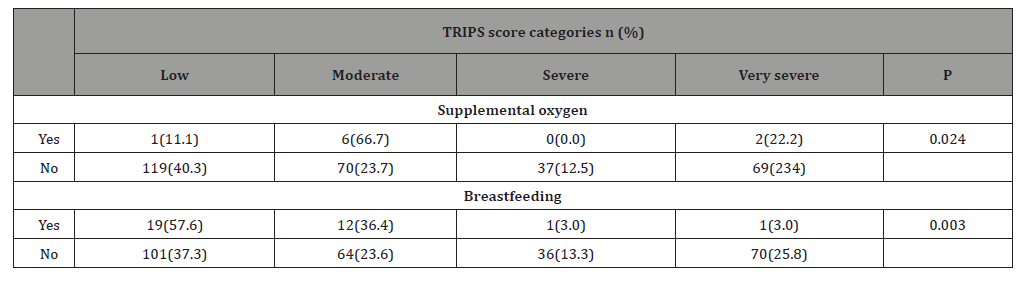

Table 3 shows there were statistically significant associations between care received before and during transportation and TRIPS scores. It was observed that neonates who received supplemental oxygen and breastmilk before and during transport were more in the low and moderate than high categories of TRIPS scores.

Table 3:Pre-and intra-transport care and TRIPS score of 382 neonates.

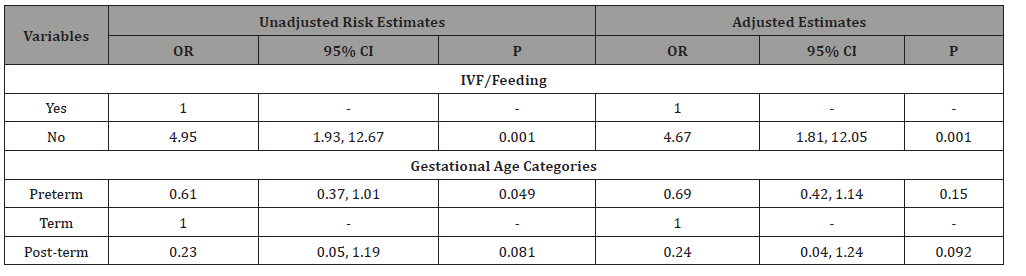

Risk factors associated with mortality

After adjusting for gestational age in a logistic regression analysis, only administration IVF or breastmilk was significantly associated with outcomes on admission and in the first 48 hours. Those neonates who were not given IVF/breastmilk had a higher odd of mortality than those given (OR = 4.67; 95% CI = 1.81, 12.05) as shown in Table 4.

Table 4:Risk factors associated with mortality following transport.

Discussion

This follow up data of our initial publication [7] show that the immediate outcomes of referred neonates in Ibadan, Nigeria is less than optimal and it is possible that inadequate pre and intratransport care, especially with respect to sugar control contributed to their poor condition on arrival at the tertiary hospital. This was evident from the TRIPS scores in which almost a half of the babies presented with severe and very severe score categories. It might be difficult to conclude with certainty that their conditions were related to the transport alone, as we do not have the benefit of TRIPS score prior to transport. These poor states on arrival put the neonates at comparatively disadvantaged situation for survival, given the limited facilities for intensive care in tertiary hospitals in resource limited settings like ours.[25] The median TRIPS score of 21 on arrival, and severity of the babies’ conditions in this study are is similar to those reported by Gustavo et al[26] in Argentina which was also associated with high mortality. Though the pre-transport TRIPS scores were not assessed in the present study, and the degree of deterioration attributable to transport could not be quantified, but it is worthy of note that those who had some form of care during transport had lower scores and this underscores the importance of paying urgent attention to the deplorable transport practices available to this neonates if they are to benefit from the referral [7].

Looking at the individual measures of immediate morbidity namely; hypothermia, hypoxaemia, hypoglycaemia, metabolic acidosis and apnoea, those babies that received some pre- and intra-transport care such as resuscitation, intravenous fluids/ feeding or oxygen therapy expectedly had less of these problems. This observation is similar to what was previously documented in previous studies in Argentina [4,5]. Proper hydration and optimal glycaemic control help in maintaining good cardiovascular stability and general homeostasis. Problems of electrolyte derangement, dehydration, cerebral hypo-perfusion and injury, renal hypoperfusion amongst others would be greatly minimized with proper hydration and optimal glycaemic control irrespective of underlying pathology. It is therefore expedient to pay attention to transport practices from communication, stabilization pretransport to actual intratransport care at all levels and is probably more important in developing countries where the greatest burden of neonatal morbidity and mortality is. Studies evaluating pre and post transport assessment using the TRIP score or other simple assessment tools to quantify the actual magnitude of the effect of suboptimal transport on neonatal outcomes in such settings are necessary at this point.

In the present study overall mortality among the study participants (if BIDs were included) within 48 hours of was 22.2%. Though this is much lower than the 55.2% mortality recorded within 48 hours by Harmesh et al. [4] in India in 1996, but is still unacceptably high, and their study, having been conducted almost 2 decades earlier when neonatal care in developing countries had not received utmost attention, may account for this difference. If neonatal outcomes are to be improved and consequently child mortality is to be significantly reduced, adequate attention to transport practices must be included in the various newborn survival packages.

Considering the peculiarity of the Nigerian referral system and scarce resources which may not always permit assessment of all the parameters in the existing neonatal transport scoring systems, it might be useful to develop locally adaptable simple scoring systems. This can be used for the assessment of clinical outcomes of newborns pre and post transportation from one healthcare facility to another in Nigeria and similar LMICs.

From the findings of this study, it is clear that there is the need to address pre-transport stabilization and care as well as intra transport in newborn care packages. Appropriate supervising authorities need to ensure compliance with existing guidelines for referral of sick neonates using the prototype referral proforma and practice of KMC for neonatal transport where transport incubators are not available. In addition, consideration should be given to the provision of appropriately equipped neonatal transport teams to be domiciled at the secondary and tertiary centers and called upon when needed. This is very feasible now in the light of widespread use of mobile phones in the country.

Conclusion

Outborn neonates referred to the University College Hospital had significant morbidity on presentation and is associated with poor neonatal transport practices. It is important to address the issue of pretransport stabilization and intratransport care of newborns in order to achieve the desired aim of referral.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Agarwal R, Agarwal K, Acharya U, Christina P, Sreenivas V, et al. (2007) Impact of simple interventions on neonatal mortality in a low-resource teaching hospital in India. J Perinatol 27(1): 44-49.

- (2015) UNICEF Maternal and child health. New York, USA.

- Raju TNK, Vidyasagar D (1982) Neonatal transportation, taking intensive care to the infant. In: Aladjem S, Vidyasagar D, editors. Atlas of Perinatology. London: WB Saunders 313-316.

- Harmesh S, Daljit S, Jain B (1996) Transport of referred sick neonates, how far from ideal? Indian Pediatr 33(10): 851-853.

- Chance GW, O’Brien MJ, Swyer PR (1973) Transportation of sick neonates, an unsatisfactory aspect of medical care. Can Med Assoc J 109(9): 847-851.

- National Population Commission (NPC) (2014) [Nigeria] and ICF International. Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, and Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- Abdulraheem MA, Tongo OO, Orimadegun AE, Akinbami OF (2016) Neonatal transport practices in Ibadan, Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J 24: 216.

- Britto J, Nadel S, Maconochie I, Levin M (1995) Morbidity and severity of illness during interhospital transfer: impact of a specialized pediatric retrieval team. BMJ 311(7009): 836-839.

- Agostino R, Fenton AC, Kollée LAA (1999) Organization of neonatal transport in Europe. Prenat Neonatal Med 4: 20-34.

- Leslie AJ, Stephenson TJ (1997) Audit of neonatal intensive care transport: closing the loop. Acta Pediatr 86(11): 1253-1256.

- Thwaites M, Pearson CA (1973) Neonatal care in the tropics (review of a new unit). J Trop Pediatr Environ Child Health 19(2): 98-100.

- Sutcuoglu S, Celik T, Alkan S, Ilhan O, Ozer EA (2015) Comparison of Neonatal Transport Scoring Systems and Transport-Related Mortality Score for Predicting Neonatal Mortality Risk. Pediatric emergency carem 31(2): 113-116.

- Dedeke IOF, Okeniyi JAO, Owa JA, Oyedeji GA (2011) Point-of-admission neonatal hypoglycaemia in a Nigerian tertiary hospital: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Journal of Pediatr 38(2): 90-94.

- Ogunlesi TA, Ogunfowora OB, Adekanmbi AF, Fetuga MB, Olanrewaju DM (2008) Point-of-admission hypothermia among high-risk Nigerian newborns. BMC Pediatr 8: 40.

- Orimadegun AE, Akinbami FO, Akinsola AK, Okereke JO (2008) Contents of referral letters to the children emergency unit of a teaching hospital, southwest of Nigeria. Pediatr Emerg Care 24(3): 153-156.

- Lee SK, Zupancic JA, Sale J, Pendray M, Whyte R, et al. (2002) Cost-effectiveness and choice of infant transport systems. Medical Care 40(8): 705-716.

- Hermansen MC, Hasan S, Hoppin J, Cunningham MD (1988) A validation of a scoring system to evaluate the condition of transported very-low-birthweight neonates. Am J Perinatol 5(1): 74-78.

- Ferrara A, Atakent Y (1986) Neonatal stabilization score: a quantitative method of auditing medical care in transported newborns weighing less than 1,000 g at birth. Med Care 24(2): 179-187.

- Lee SK, Zupancic JA, Pendray M, Thiessen P, Schmidt B, et al. (2001) Transport risk index of physiologic stability: a practical system for assessing infant transport care. J Pediatr 139(2): 220-226.

- World Health Organization (1997) Thermal Protection of the Newborn: A Practical Guide.

- Committee on Fetus and Newborn, David HA (2011) Postnatal glucose homeostasis in late-preterm and term infants. Pediatr 127(3): 575-579.

- Meayoung C (2011) Optimal oxygen saturation in premature infants. Korean J Pediatr 54(9): 359-362.

- Avery's Diseases of the Newborn (2005) Care of the High- Risk Infant. 8th Taeusch WH, Ballard R A, Gleason CA (Eds), Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, USA.

- Karlsen KA (2006) Post-resuscitation/Pre-transport Stabilization Care of Sick Infants: Guidelines for Neonatal Healthcare Providers. 6th Park city, Utah, USA.

- Amadi HO, Mokuolu OA, Adimora GN, Pam SD, Etawo US, et al. (2007) Digitally recycled incubators: better economic alternatives to modern systems in low-income countries. Ann Trop Paediatr 27(3): 207-214.

- Gustavo G, Cecilia R, Susana R, Yanina A (2012) Risk factors associated with clinical deterioration during the transport of sick newborn infants. Arch Argent Pediatr 110(4): 304-309.

- Orimadegun EA, Akinbami FO, Tongo OO (2008) Comparison of Neonates Born Outside and Inside Hospitals in a Children Emergency Unit, Southwest of Nigeria. Ped Emerg Care 24(6): 354-358.

-

Tongo O, Abdulraheem M A, Orimadegun A E, Akinbami F O. Immediate Outcomes of Neonatal Transport in a Tertiary Hospital in South-West of Nigeria. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 2(1): 2020. GJPNC.MS.ID.000529.

Outcomes, Neonatal, Transport, TRIPS, Nigeria, Neonates, Newborns, Morbidity, Mortality, Hospital, Hypoglycaemia, Pre-transport, Oxygen

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.