Review Article

Review Article

An Overview of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Infants and Toddlers: A Review Article

Volkan Sarper Erikci*

Professor of Pediatric Surgery, Sağlık Bilimleri University, Turkey

Volkan Sarper Erikci, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Sağlık Bilimleri University, İzmir Faculty of Medicine, İzmir-Turkey

Received Date: October 24, 2021; Published Date: December 17, 2021

Abstract

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) in infants and toddlers is commonly encountered in clinical practice. There are several factors producing LGIB in these children and are usually managed with regard to the underlying pathology that produces LGIB. Although majority of these bleeding episodes is self-limited, certain infants and toddlers with LGIB may necessitate prompt management including urgent surgical intervention. In this review article it is aimed to review the etiology, epidemiology, clinical manifestations and principles of treatment of LGIB in infants and toddlers under the light of relevant literature.

Keywords: Lower gastrointestinal bleeding; Infants and toddlers; Etiology

Introduction

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) in infants and toddlers is commonly encountered in daily clinical practice [1-5]. LGIB is defined as blood in the stool derived from lesions originating from any location in the gastrointestinal tract distal to the ligament of Treitz which determines the duodenojejunal junction. Of the children presenting to the hospital with rectal bleeding, approximately onethird have LGIB and the remaining have either bleeding originating from upper gastrointestinal tract or bleeding with unclear etiology [6]. Hopefully only 5-10 percent of these cases show findings of severe gastrointestinal bleeding necessitating prompt management [1,6]. Stools in these children may be in the form of hematochezia as bright red or pink, melena as tar-like substance or blood may not be visible by eye indicating occult bleeding which can be detected by laboratory tests. In this review article it is aimed to overview common causes of LGIB in infants and toddlers together with therapeutic options in the management and the literature on this issue is also reviewed for readers.

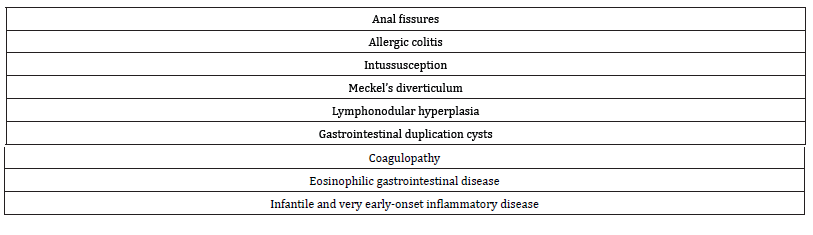

There are several etiological factors for LGIB in infants and toddlers (one month to 2 years of age). These are depicted in Table 1.

Table 1:The most common causes of LGIB in infants and toddlers.

Anal Fissures

Infants and toddlers usually present with constipation associated with anal fissures following the introduction of solid foods or cow’s milk into the diet, during toilet training or at the time of entry to school. Most of the previous reports have documented that constipation with anal fissure formation is the most common cause of LGIB in toddlers and school age children [7-9]. The diagnosis of anal fissure is easy by everting the anal canal the fissure can easily be seen at the usual position of 6 or 12 o’clock at supine position. If the medical history of the infant reveals painful defecation together with straining, straining associated with withholding of feces during defecation manoeuvres, observation of streaks of red blood on the surface of feces, it is likely that the child has anal fissure. Management of constipation by dietary regulations and medications together with sitz baths and topical therapy including analgesics is all that is needed for cure of the disease.

Allergic Colitis

This entity is also called as milk or soy protein induced colitis. Prolonged vomiting and bloody diarrhea are classic symptoms of cow’s milk allergy in infants. If untreated, with the progression of the disease, dehydration may be seen especially in infants younger than 3 months of age [10]. In severe and untreated cases with a long history malabsorption, protein-losing enteropathy and failure to thrive may result. Hopefully usual course of the disease is selflimited and does not cause weight loss or failure to thrive. Food allergy usually resolves within 6-18 months of age.

Intussusception

Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in infants between 6-36 months of age. Majority of children with intussusception are younger than 2 years. Intussusception in this age group is usually idiopathic without any lead point whereas older children present with different kinds of lead point producing intussusception like a polyp, Meckel’s diverticulum. Typically, the infants may awaken from sleep with abdominal pain and draw up their legs into the abdomen. Colicky abdominal pain is the usual finding in these children. The stool usually contains gross or occult blood in most of the children and as the disease progresses the characteristic “currant jelly” appearance may be seen in the stool. Eventually the child becomes apathetic and a sausage shaped mass may be palpable. Ultrasonography is the method of choice in diagnosing the intussusception in majority of cases and it also permits reduction of intussusception during the study. If ultrasonographic findings are inconclusive for the diagnosis of intussusception, a water soluble contrast enema under fluoroscopic guidance may be an alternative means of imaging study for both diagnosis and treatment. These children should be managed promptly beginning with intravenous fluid and electrolyte infusion, nasogastric decompression. If any restrictive circumstances do not exist like intestinal perforation, reduction of intussusception by aforementioned radiological methods should be performed urgently. Surgical intervention may be necessary in whom the intussusception cannot be reduced radiologically or a complication like intestinal perforation occurs.

Meckel’s Diverticulum

Meckel’s diverticulum is the most common congenital anomaly of the gastrointestinal tract. It is a true diverticulum containing all layers of the bowel wall [11]. Most cases of Meckel’s diverticulum are asymptomatic and those cases that contain ectopic gastric mucosa are generally associated with bleeding which is painless in general. The diagnosis of a bleeding diverticulum is by Meckel’s scintigraphy which has a sensitivity of 85-97%. The treatment of Meckel’s diverticulum is resection of diverticulum.

Infectious Colitis

There are several pathogens which can cause LGIB during infancy. Most common of these are Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, E. coli 0157:H7, and Clostridioides difficile. Especially immunocompromised children may be affected by potential pathogens including Mycobacteria and Aeromonas hydrophilia although Aeromonas infection typically presents with non-bloody diarrhea but in some cases diarrhea containing blood may also be seen during the disease process. Occasionally Neisseria gonorrhea, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Plesiomonas shigelloides can occasionally produce bloody stools. The diagnosis of infectious colitis is usually made by isolating the microorganism from the stool or blood. These children usually present with rectal bleeding accompanied by fever, abdominal pain, tenesmus and small pieces of small bloody stools. The treatment of infants with infectious colitis depends on the underlying pathogenic agent that produces infectious colitis and these children should be treated accordingly.

Lymphoid Nodular Hyperplasia

This is one of the most common causes of LGIB in infants and toddlers and is an unlikely source of rectal bleeding in older children [12]. These lesions are characterized by multiple, yellowish lymphoid follicles in children who undergo endoscopic examination of gastrointestinal tract. Although most authors consider these lesions to be a normal finding other believe that they are due to an immunologic response of body to a variety of stimulants [13- 17]. Lymphoid nodular hyperplasia is usually asymptomatic and resolves spontaneously but sometimes needs dietary restriction and occasional steroid medication [18].

Gastrointestinal Duplication Cysts

Gastrointestinal duplication cysts can be found at any level of the gastrointestinal tract and often do not communicate with the intestinal lumen. Almost half of the gastrointestinal duplication cysts contain gastric mucosa and may form fistulas between colon and stomach which may be the source of LGIB in infants. Although not so often, gastric duplication cyst that contains ectopic mucosa may produce a communication between stomach and colon producing LGIB. In addition, when it communicates with the intestinal lumen it may also produce LGIB necessitating hospital admission. Treatment option of LGIB produced by gastrointestinal duplication cysts depends on the anatomic location of the duplication cysts and should be managed surgically

Other Causes

Other causes of LGIB in infants and toddlers include very early-onset inflammatory bowel disease, coagulopathy, brisk upper gastrointestinal bleeding, vascular malformations, gastric or duodenal ulcers and other rare causes of LGIB. Gastrointestinal bleeding related to any of these pathologies should be managed by eliminating the causative factors that produce blood in the stool together with an appropriate treatment modality.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LGIB in infants and toddlers can be a presenting symptom of various underlying disease states. Although minority of infants and toddlers show severe bleeding signs, a systematic approach for diagnosis of underlying lesions and a prompt management including sometimes surgical intervention is paramount. The medical providers should keep causative factors of LGIB in infants and toddlers and a rapid pediatric surgery consultancy is recommended. These children should receive appropriate treatment immediately.

Funding

During this study, no financial or spiritual support was received neither from any pharmaceutical company that has a direct connection with the research subject, nor from a company that provides or produces medical instruments and materials which may negatively affect the evaluation process of this study.

Author Contribution to the Manuscript

Idea/concept, design, control and processing, analysis and/or interpretation, literature review, writing the article, critical review, references and materials by Volkan Sarper Erikci.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest

The author certifies that he has no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest, or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

- Teach SJ, Fleisher GR (1994) Rectal bleeding in the pediatric emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 23(6): 1252-1258.

- Khurana AK, Saraya A, Jain N, Chandra M, Kulshreshta R (1998) Profile of lower lower gastrointestinal bleeding in children from a tropical country. Trop Gastroenterol 19(2): 70-71.

- Dupont C, Badoual J, Le Luyer B, Le Bourgeois C, Barbet JP, et al. (1987) Rectosigmoidoscopic findings during isolated rectal bleeding in the neonate. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 6(2): 257-264.

- Perisic VN (1987) Colorectal polyps: an important cause of rectal bleeding. Arch Dis Child 62(2): 188-189.

- Cucchiara S, Guandalini S, Staiano A, Devizia B, Capano G, et al. (1983) Sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, and radiology in the evaluation of children with rectal bleeding. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2(4): 667-671.

- Pant C, Olyaee M, Sferra TJ, Gilroy R, Almadhoun O, et al. (2015) Emergency department visits for gastrointestinal bleeding in children: results from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample 2006-2011. Curr Med Res Opin 31(2): 347-351.

- Rayhorn N, Thrall C, Silber G (2001) A review of the causes of lower gastrointestinal tract bleeding in children. Gastroenterol Nurs 24(2): 77-82.

- Leung AK, Wong AL (2002) Lower gastrointestinal bleeding in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 18(4): 319-323.

- Hillemeier C, Gryboski JD (1984) Gastrointestinal bleeding in the pediatric patient. Yale J Biol Med 57(2): 135-147.

- Aanpreung P, Atisook K (2003) Hematemesis induced by cow milk allergy. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 21(4): 211-216.

- Moore KL, Persaud TV (2007) The developing human: clinically oriented embryology. 8th Philadelphia: Saunders, pp. 255-286.

- Colon AR, DiPalma JS, Leftridge CA (1991) Intestinal lymphonodular hyperplasia of childhood: patterns of presentation. J Clin Gastroenterol 13(2): 163-166.

- Chiche A, Gottrand F, Turck D, Francillette K, Farriaux JP (1990) Proctorrhagia secondary to lymphonodular hyperplasia revealing a food allergy. Arch Fr Pediatr 47(3): 207-209.

- Tuck D, Michaud L (2004) Lower gastrointestinal bleeding. In: Pediatric Gatsrointestinal Disease, 4th, Walker WA, Goulet O, Kleinman RE, et al. (Eds), BC Decker Inc, Hamilton, Ontario, pp. 266.

- Riddelsberger MM Jr, Lebenthal E (1980) Nodular colonic mucosa of childhood: normal or pathologic? Gastroenterology 79(2): 265-270.

- Franken EA Jr (1970) Lymphoid hyperplasia of the colon. Radiology 94(2): 329-334.

- Kokkonen J, Karttunen TJ (2002) Lymphonodular hyperplasia on the mucosa of the lower gastrointestinal tract in children: an indication of enhanced immune response? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 34(1): 42-46.

- Zahmatkeshan M, Fallahzadeh E, Najib K, Geramizadeh B, Haghighat M, et al. (2021) Etiology of lower gastrointestinal bleeding in children: a single center experience from southern Iran. Midle East J Dig Dis 4(4): 216-223.

-

Volkan Sarper Erikci. An Overview of Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Infants and Toddlers: A Review Article. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 4(1): 2021. GJPNC.MS.ID.000577.

Lower gastrointestinal bleeding, Infants and toddlers, etiology, Treatment, Blood, Anal fissure, Allergy, Abdominal pain, Children, Duplication cysts

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.