Research article

Research article

Risk factors for Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Very Preterm Infants- A Retrospective Observational Case-Control study

Nusrat Khan1*, Ahmed Elhidadi1, Uzma Afzal1, Amal Yahyi1, Mohammad Farah Osman1, Ela Bayuni1, Aiman Rahmani1 and Hassib Narchi2

1Department of Neonatology, Tawam Hospital Alain

2Department of Pediatrics, UAE University Alain

Nusrat khan, Department of Neonatology, University of Tawam Hospital, United Arab Emirates

Received Date:December 09, 2024; Published Date:December 19, 2024

Abstract

Background: Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an inflammatory disease of the intestine of variable severity, mainly affecting the gut of preterm infants. Multiple antenatal, natal, and post-natal factors play a role in the development of NEC. Despite improvements in neonatal care of very preterm infants, it continues to occur in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs).

Aims and objectives: To assess and remove any possible collinearity among specific factors involved in the development of NEC in very preterm

infants and determine the role of some understudied factors, such as multiple pregnancies.

Methods: A retrospective case-controlled study design was used to determine the association of multiple prenatal, natal, and post-natal factors with the development of NEC in very preterm infants. Ten years of data for preterm infants between the gestational ages of 23+0/7 and 31+ 6/7 weeks was reviewed; of the 933 inborn infants, 84 cases of NEC were identified and used while 88 cases were taken as the control group. By using

multiple logistic regression, these variables were assessed for independent association with the development of NEC and checked for collinearity

among the risk factors.

Results: As result of univariate analysis, multiple pre-natal, natal, and post-natal factors showed significant association with development of NEC, either positively or negatively. However, in multivariate analysis, only a few variables showed an independent association. Of these, the invasive ventilation and late onset sepsis (LOS) significantly increased the risk of NEC in very preterm infants with the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 3.03 and 4.7 respectively while prolonged duration of antibiotics for LOS significantly decreased the risk of NEC with aOR of 0.84.

Conclusion: Only few factors have shown independent association with the development of NEC; further multicenter prospective studies are

needed to carry out to determine the role of main factors in development of NEC and to devise the strategies to decrease rate of NEC in NICUs.

Keywords:Neonatal Intensive Care Unit; Neonate; Complications of central venous catheters

Abbreviations:NEC; Risk factors; (Antenatal, natal, postnatal); Very preterm

Introduction

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an inflammatory disease affecting the newborn intestines with variable severity ranging from mere epithelial injury to transmural involvement and perforation [1]. This mainly afflicts premature infants and is characterized by variable intestinal injury; advanced stages are often associated with high morbidity and mortality [2]. The incidence of NEC in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) varies from 5 to 15% with an even higher incidence as advancement in technology has increased the survival of extreme premature babies including 23-24weeks of gestation [1- 5]. Despite the improved neonatal care of very premature babies in NICUs and preventive antenatal and postnatal care, such as use antenatal steroids and MgSO4, exclusive breast milk (EBM) or probiotics, NEC remains relatively common in most of NICUs [1,3- 7]. The reason is likely to it being a multifactorial disease related to low Apgar scores, small of gestational age (SGA), chorio-amnionitis and antibiotic use in mother, presence of a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), blood transfusion, as well as nosocomial infections [1,6]. However, the relative contribution of these individual risk factors remains unknown: which ones play a major role in the process of initiating NEC and which ones may be aggravating it [1,6,8,9] One possible reason for this is that most previous studies did not take into account the existence of possible correlation among those risk factors, thereby leading to multicollinearity which would not have allowed to distinguish between the individual effects of these independent variables [10]. Additionally, multiple pregnancies and its complications are reported as risk factors for NEC in premature infants, but no well-designed studies have been carried out to determine the association of these factors to NEC [11,12].

The aim of this retrospective observational case-control study is to assess and remove any possible collinearity among those specific factors involved in the development of NEC in very preterm infants and also to determine the role of some understudied factors including multiple pregnancies in the development of necrotizing enterocolitis in these infants.

Methods

This is a single center retrospective case-control study conducted in a tertiary care NICU in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). We reviewed the electronic medical records of all very preterm infant (gestational age <32+0/7 weeks at birth) who were admitted to the NICU from 1st January 2011 to 31st December 2020. Ethical approval was granted by our institutional review board (MF2058- 2020-775, approved in March 2021). Parental informed consent was waived as this was a retrospective observational study. We excluded infants with intestinal congenital malformation, cyanotic heart disease, immunodeficiency, disorders of inborn errors of metabolism and those with insufficient relevant information or for whom eligible controls were unavailable.

Collected data included gestational age as per LMP and ultrasound in first trimester (GA), gender, birth weight (BW) and ethnicity. Prenatal risk factors included premature prolonged rupture of membranes >18 hours (PPROM), clinical chorioamnionitis if mother had fever with elevated serum CRP concentrations and white blood cell (WBC) count or febrile with foul smelling liquor and labelled as having chorioamnionitis by the attending obstetrician. We also recorded maternal exposure to antibiotics, antenatal corticosteroid therapy (4 or 2 doses of dexamethasone or betamethasone respectively with the last dose completed 12 hours before delivery), pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH), pre gestational diabetes mellitus, maternal obesity (BMI>30 kg/m2), abruptio placentae, number of fetuses, whether spontaneous or induced medically or by in-vitro fertilization (IVF) including intracytoplasmic sperm insemination(ICSI). We also recorded the presence of abnormal Döppler ultrasound of the umbilical artery (absent or reverse diastolic flow), growth status in-utero and at birth: intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) demonstrated by serial antenatal ultrasounds, small for gestational age (SGA) when birth weight (BW) <10th centile for gestation, appropriate for gestation (AGA) when BW between 10th and 90th centile and large for gestational age (LGA) if BW was > 90th centile for the gestational age and examination. Natal risk factors included mode of delivery, APGAR scores at 1, 5 and 10 min, and delayed cord clamping (DCC ) >30sec. Post-natal risk factors included hypothermia on admission (rectal temperature <36.5C0), metabolic acidosis in the first 48 hours of life (absent or minimal if Ph was, 7.2 or more with base deficit less than 6 mmol/L, moderate when base deficit was 6-12 with Ph <7.2 and severe if it is more than 12 and Ph <7.1) and was considered persistent if demonstrated in > 3 blood gases measurements done in the first 48 hours. We also recorded the mean blood pressures of the patients, measured either intravascularly or by a non-invasive method, hypotension was defined as the mean blood pressure is >=2 mmhg below gestational age of patient and required ionotropic support. The duration of indwelling umbilical catheters, mode of ventilation either invasive or noninvasive, also noted, conventional ventilation or high frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV) when continued for > 48 hours are classified as invasive ventilation and noninvasive or minimally invasive when tracheal intubation was never required or required intubation for < 48 hours. The data on number of doses of surfactant administered (from 0 to 4 times) and FiO2 requirements during first week of life classified into 3 groups: always < 25%, between 25-40% and > 40%, was collected as well. Additional collected data included the demonstration of a hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) on echocardiography and requiring pharmacological treatment (with either ibuprofen or paracetamol), the diagnosis of early and late onset sepsis (EOS or LOS) with or without causative organisms (clinical sepsis with the latter) before occurrence of NEC in cases and for first 6 weeks of life in controls, duration of antibiotic therapy, lowest hemoglobin (Hb) level, number of erythrocyte transfusions, and feeding practices during these transfusions. Information was also gathered on enteral feeding (type of milk, volume administered at the time of NEC, rate of increment, age at initiation of feeds, total duration of withholding feeds (NPO) before the occurrence of NEC, administration of probiotic and of H2 receptor blockers.

Definitions

NEC cases (ICD10: P77.2, P77.3) were defined as infants diagnosed with NEC stage ≥ 2 (modified Bell’s classification [13]; any patient with intestinal perforation was also taken as NEC (case) because without laparotomy or autopsy we were not able to differentiate spontaneous intestinal perforation (SIP) from the perforation due to NEC as they were managed in the same way. One control was taken against each case (1:1) and controls were selected from infants who were admitted within six months of index cases and of the same gestation ± 1 week and same birth weight ± 100 grams as of the case and did not develop NEC till discharge.

Early-onset sepsis (EOS) was defined when an infant required antibiotics for ≥ 5 days with clinical and laboratory criteria for sepsis in the first 72 hours of life and Late-onset sepsis (LOS) was defined if an infant required antibiotics for 5 days or more after the first 72 hours of life. The sepsis (EOS/LOS) was categorized as clinical sepsis or culture proven sepsis. Clinical sepsis was defined as the presence of signs of sepsis (e.g., temperature instability, apnea, tachypnea, hemodynamic instability) along with the elevated serum CRP concentration or abnormal blood counts, with a sterile blood culture, while the culture proven sepsis was defined as the presence of clinical symptoms and signs along with isolation of a pathogen from a blood culture. Duration of antibiotics was defined as the cumulative number of days given intravenous antibiotics before the occurrence of NEC in cases and during first 6 weeks for the controls.

Enteral feeding types were defined as:

1) Excusive breast milk feeding (average daily feeding

volume with ≥80% breast milk)

2) Formula fed (average daily enteral feeding volume with

≥80% formula)

3) Mixed feeding (infant fed formula up to 50% of total

feeds).

Full enteral feeding was defined when no additional parenteral feeding (amino acids or lipids) was administered for ≥ two consecutive days. Parenteral feeding duration was defined as the cumulative number of days any nutritional solution (lipids or amino acids) was administered parenterally. The day of initiation of first feed was categorized as either within 3 days or after 3 days. The cumulative number days of absent enteral feeding (NPO) was calculated before the onset of NEC and during the first three weeks for controls. Increments in feeding volumes during the first two weeks postnatally were defined as the daily increase in enteral feeding volume relative to the birth weight (ml/kg/day).

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 21 (IBM, Armonk, New York) and Stata version 17 (Stata Corp, Texas) statistical packages were used for analysis. For this casecontrol study with a ratio of cases to controls of 1:1 and estimating a prevalence of NEC of 10%, a sample size of 80 cases and similar number of controls was required to give the study 80% power with 95% confidence.

The prevalence of NEC in inborn VLBW infants was calculated with its 95% confidence intervals. For the univariate analysis the two-sample Student t-test was used to compare normally distributed continuous variables expressed as mean & SD, and the Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare variables not following a normal distribution, expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). For categorical data, the Chi squared and the Fisher exact test were used to compare proportions. The association between each factor and the outcome was expressed as unadjusted odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

A multivariate logistic regression model was constructed using only the variables associated with the outcome in the univariate analysis with P<0.1. As some risk factors might be highly correlated with one another, and therefore not be completely independent, multicollinearity might have occurred in the multivariate model and would have prevented distinction between the individual effects of these independent variables. We therefore also tested for multicollinearity by calculating those variables inflation factors (VIF) which represent how well each explanatory variable is explained by the others. A VIF score ≥10 for a variable indicates high multicollinearity with others and so it was removed from the regression model before testing the multivariate model again. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% CI were reported for the final regression model with a P value <0.05 defining statistical significance.

Results

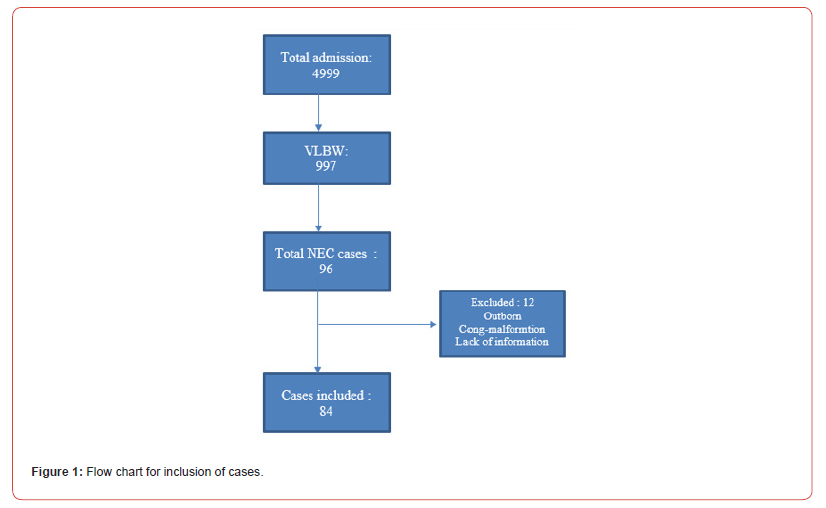

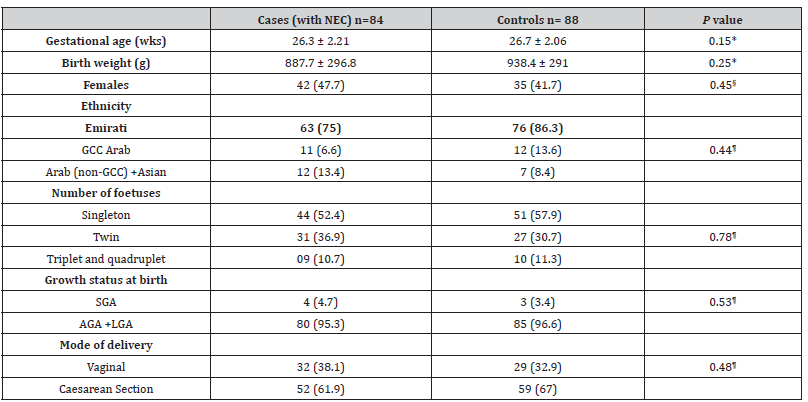

During the study period, 4995 infants were admitted to the NICU, including 997 very preterm infants which contributed about 20% of NICU admissions. Out of these, 933 were inborn (93.5%) as shown on Figure 1. NEC was identified in 96 neonates, resulting in a NEC prevalence of 9.6% in very preterm infants (95% confidence intervals 7.9, 11.6%). The median age [interquartile range] when NEC occurred was 9 days [5.5, 14]. Controls included 88 neonates without NEC. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The majority of patients were of Emirati origin and there is predominance of females in NEC cases but not significant statistically, other characteristics are similar in both groups. The rate of NEC was 9% among inborn infants while the median age of development of NEC was 9 days of life with IQR of 5, 14.

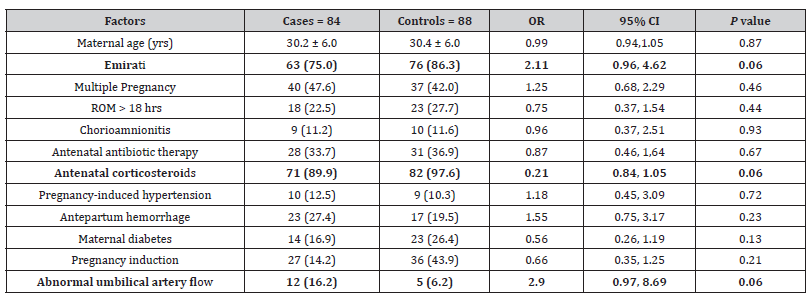

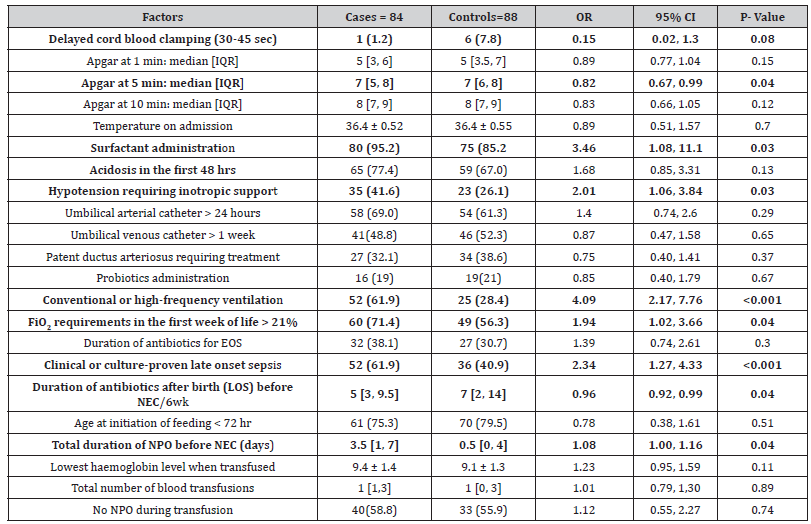

In the univariate analysis, except few, most of the factors did not show statistically significant effect in the development of NEC (Table 2 A & 2B). Of the prenatal factors, Antenatal administration of corticosteroids showed protective effect on NEC with odds ratio of 0.21 while the abnormal Doppler has increased the risk of NEC almost by 3 folds with the OR 2.90 but both of these did not have statistically significant impact in either way (table 2A). From natal and post-natal factors, delayed cord clamping, APGAR Score (A/S) at 5 minutes, longer duration of antibiotics in LOS showed low risk (OR <1) of developing NEC in univariate analysis (table 2B). The variables which showed significant impact on development of NEC in univariate analysis are high FiO2 requirement (OR 1.94), longer duration of NPO (OR 1.08); some variables even have 2 or more-fold increment in the risk of NEC, including hypotension requiring inotrope, surfactant administration, invasive or advanced ventilation, and late onset sepsis with ORs of 2.1, 3.46, 4.09 and 2.34 respectively (Table 2B).

Table 1:Participants’ characteristics. Results expressed as number (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median [interquartile range].

For gesttaopna; age; NEC: necrotizing enterocolitis; GCC: Gulf Cooperation Council; SGA, AGA, LGA: small, appropriate and large for gestational age; * Two-sample t-test; § Kruskal-Wallis test; ¶ Chi squared test.

Table 2A:Prenatal factors associated with necrotizing enterocolitis in 84 preterm neonates (<32 weeks) Results expressed either as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence intervals

Table 2B:Natal and postnatal factors associated with necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in 84 preterm neonates (<32 weeks) Results expressed either as number (%), or median [IQR] or mean ± standard deviation.

OR: odds ratio, CI: confidence intervals

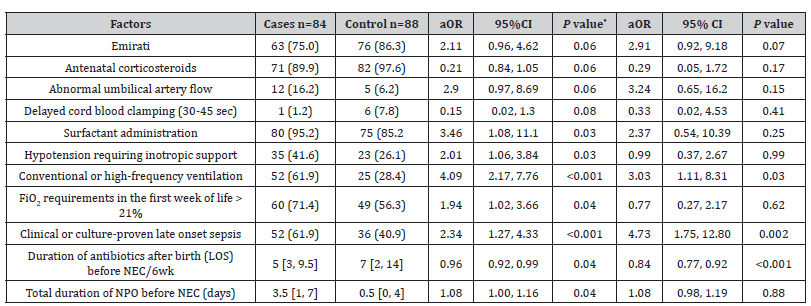

Multivariate analysis: only two variables (maternal corticosteroid administration and infant’s Apgar score at 5 minutes) showed strong collinearity (VIF > 10). Excluding the 5-minute Apgar score from the multivariate model removed any collinearity and this new model was retained. The multivariate analysis showed that from the 11 risk factors in the multivariate model, only 3 variables were significantly associated with the development of NEC: conventional or high-frequency ventilation (aOR 3.03), and clinical or culture-proven LOS (aOR 4.73) increased the odds of developing NEC, while prolonged duration of antibiotics for LOS was protective against it (aOR 0.84) (Table 3).

Table 3:Factors associated with necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) in 84 preterm neonates (<32 weeks) after correction for multicollinearity. Results expressed either as number (%), mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range].

OR: odds ratio; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence intervals

Discussion

The prevalence of stage II and above NEC among inborn patients was 9%, comparable to some centers in Canada, higher than others reported in both the Canadian (CNN) and Australian New Zeeland (ANZN) network annual summaries [14-16] but lower than those in low-income countries [17]. The median postnatal age of 9 days (IQR 5, 14) is quite similar to other studies which reported its occurrence mainly within the first three weeks of life [9]. Most of the risk factors significantly associated with the development of NEC in the univariate analysis lost their significant association in the multivariate analysis, showing that were not independently associated with that outcome. The reason is most likely due to the presence of many confounding factors.

The only three independent risk factors for the odds of developing NEC were the use of conventional or high-frequency ventilation, the occurrence of LOS and the duration of antibiotic therapy for LOS. The use of conventional or high-frequency ventilation significantly increases the odds of NEC (aOR =3.03), confirming earlier studies [18]. This could be explained by possible gut ischemia in neonates with respiratory failure. The occurrence of LOS also independently and significantly increased the odds of developing NEC in VLBW infants (aOR= 4.73) again, confirming the previous studies where nosocomial infections has strong positive correlation with NEC [18]. Interestingly, the longer duration of antibiotic therapy for LOS, independently and significantly, decreased the odds of developing NEC in VLBW infants (aOR= 0.84) One possible explanation is that, as infection is a risk factor for NEC, an adequate duration of antibiotic treatment might mitigate the association of sepsis with NEC in such infants.

The antenatal administration of corticosteroids, found in previous reports to decrease the risk of NEC by almost 50% [19], was not an independent variate in our study as confirmed by others [20]. Similarly, abnormal umbilical artery flow, previously associated with the development of NEC [21,22] was not an independent risk factor either. Neither APH nor abruptio-placenta showed a significant independent association with NEC; however, this may be due to the fact that our study included only the inborn infants where immediate deliveries were conducted when indicated, precluding therefore the compromise of blood supply to fetus which might have caused gut ischemia. The lack of association of PIH or PROM with NEC confirms earlier reports [23].

Unlike previous studies where histologically proven chorioamnionitis showed an association of NEC [24], we did not confirm such association probably because we have only used clinical criteria to define chorioamnionitis resulting in a high prevalence of false-positive cases, thus invalidating such an association. Other factors, such as ethnicity, maternal age and BMI did not show any association with NEC, confirming previous reports where only black race, inexistent in our participants, was associated with an increased risk of NEC [25-27]. The presence of multiple fetuses was not a risk factor for NEC, unlike previous studies reporting an increased risk with twin pregnancies but without having a comparative group ,though one study showed increased incidence of SIP in multiple pregnancies [11,28].

Unlike some earlier studies showing an association between empiric antibiotics administration for EOS and NEC in VLBW infants, we could not demonstrate such an association as confirmed by some other reports as well [8.27,29]. Other factors, such as the Apgar scores, DCC, metabolic acidosis, hypotension, increased requirement of FIo2, duration of withholding feeds were not independently associated with NEC. The lack of association of other factors, such as delayed cord clamping, higher doses of surfactant, umbilical line, confirm previous reports [27,30-32]. Unlike a previous study, which used indomethacin for pharmacological closure of PDA [33], we did not find any significant association of hemodynamically significant PDA with NEC, confirming earlier reports [33,34]. One possible reason is that indomethacin was not used in our unit.

We did not find any significant association of probiotics administration, anemia or number of blood transfusions with NEC. A few infants were administered probiotics but only of one strain which did also not show reduction of risk of NEC in previous studies [7,35,36]. Our findings confirm earlier studies which failed to show an association between blood transfusion, number of transfusion or the Hb level when transfusion was initiated [27,37,38,39]. Although previous studies have demonstrated an association between type of feeding, age of initiation of enteral feeding and NEC, with breast milk decreasing and formula milk increasing the risk of NEC [8,40-43], our study did not find an independent association of NEC with delayed feeding (cumulative duration of NPO). With the standardized feeding policy in the unit that the majority of VLBW infants are given expressed breast milk with a standard rate of increment of feeds, we could not find any significant association between the feeding type and the rate of feed increment with NEC.

Strengths of this study, unlike previous reports, include the search for and the mitigation of the multicollinearity effect on the association between some risk factors and NEC. Limitations of our study include the fact that, with its a retrospective design, complete data was not available for all the participants, and any association found between risk factors and NEC cannot indicate causality. In addition, as it was single-center study over a 10-year period resulting in a small sample size, a multi-center study is still needed. Furthermore, a 1:2 ratio between cases and controls would have increased the study power which could not be possible due to lack of available controls according to predefined criteria.

Conclusion

Only the use of conventional or high-frequency ventilation and the occurrence of LOS independently increased the odds of developing NEC in VLBW infants, while the duration of antibiotic therapy for LOS decreased these odds. Prospective multicenter studies with large sample size are needed to be done to determine the major role of these factors in the development of the NEC and devise strategies for the prevention of NEC and its complications.

Author Contribution

1: idea, organized IRB approval, data collection, data analysis, script writing, 2: defining variables, data collection, 3: Data base creation, data collection, 4,5 and 6, data collection, 7: script reviewing. 8: Data analysis, data interpretation and script review and writing

Funding

No funding applied for the research.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to Mr Mohammad Ali khan for reviewing the script and helping us to fix the references

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Alganabi M, Lee C, Bindi E, Li B, Pierro A, et al. (2019) Recent advances in understanding necrotizing enterocolitis. F1000Research 8(1): 1-104.

- Patel RM, Ferguson J, McElroy SJ, Khashu M, Caplan MS, et al. (2020) Defining necrotizing enterocolitis: current difficulties and future opportunities. Pediatric researc 88(1): 10-15.

- Shah PS, Lui K, Sjors G, Mirea L, Reichman B, et al. (2016) Neonatal Outcomes of Very Low Birth Weight and Very Preterm Neonates: An International Comparison. The Journal of pediatrics 177(1): 144-52.

- Battersby C, Santhalingam T, Costeloe K, Modi N (2018) Incidence of neonatal necrotising enterocolitis in high-income countries: a systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition 103(2): F182-F189.

- Alsaied A, Islam N, Thalib L (2020) Global incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC pediatrics 20(1): 1-15.

- Rose AT, Patel RM (2018) A critical analysis of risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 23(6): 374-379.

- Beghetti I, Panizza JL, Gori D, Martini S, Corvaglia L, et al. (2021) Probiotics for preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: a network meta-analysis. Nutrients 13(1): 192-214.

- Berkhout DJ, Klaassen P, Niemarkt HJ, de Boode WP, Cossey V, et al. (2018) Risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis: a prospective multicenter case-control study. Neonatology 114(3): 277-284.

- Yu VY, Joseph B, Bajuk B, Orgill A, Astbury J, et al. (1984) Perinatal risk factors for necrotizing enterocolitis. Archives of Disease in Childhood 59(5): 430-434.

- Narchi H, AlBlooshi A (2018) Prediction equations of forced oscillation technique: the insidious role of collinearity. Respiratory research 19(1): 1-7.

- Burjonrappa SC, Shea B, Goorah D (2014) NEC in twin pregnancies: Incidence and outcomes. Journal of Neonatal Surgery 3(4): 45-56.

- Detlefsen B, Boemers TM, Schimke C (2008) Necrotizing enterocolitis in premature twins with twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome. European journal of pediatric surgery 18(01): 50-52.

- Walsh MC, Kliegman RM (1986) Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatric Clinics of North America 33(1): 179-201.

- The Canadian Neonatal Network Annual Report 2020.

- Australian & New Zealand Neonatal Network Report of the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network 2020.

- Sa'da OA, Khan N, Rahmani A, Al Abdullatif M (2019) Short-Term Outcomes of Very Low Birth Weight Infants at a Tertiary Care Center in UAE Compared to the World. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car 1(4): 164-196.

- Mekonnen SM, Bekele DM, Fenta FA, Wake AD (2021) The prevalence of necrotizing enterocolitis and associated factors among enteral fed preterm and low birth weight neonates admitted in selected public hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Global Pediatric Health 8(1): 1-4.

- Carter BM, Holditch-Davis D (2008) Risk factors for NEC in preterm infants: how race, gender and health status contribute. Advances in neonatal care: official journal of the National Association of Neonatal Nurse 8(5): 285-290.

- Roberts D, Brown J, Nancy M, Dalziel SR (2017) Antenatal corticosteroids for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 3(3): 1-15.

- Deshmukh M, Patole S (2018) Antenatal corticosteroids in impending preterm deliveries before 25 weeks' gestation Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition 103(2): F173-F176.

- Luig M, Lui K, NSW & ACT NICUS Group (2005) Epidemiology of necrotizing enterocolitis–Part II: Risks and susceptibility of premature infants during the surfactant era: a regional study. Journal of paediatrics and child health 41(4): 174-179.

- Dorling J, Kempley S, Leaf A (2005) Feeding growth restricted preterm infants with abnormal antenatal Doppler results. Archives of Disease in Childhood-Fetal and Neonatal Edition 90(5): F359-F363.

- Razak A, Florendo-Chin A, Banfield L, Abdul Wahab MG, McDonald S, et al. (2018) Pregnancy-induced hypertension and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Perinatology 38(1): 46-53.

- Been JV, Lievense S, Zimmermann LJ, Kramer BW, Wolfs TG, et al. (2013) Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for necrotizing enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of pediatrics 162(2): 236-242.

- Singh R, Shah B, Allred EN, Grzybowski M, Martin CR, et al. (2016) The antecedents and correlates of necrotizing enterocolitis and spontaneous intestinal perforation among infants born before the 28th week of gestation. Journal of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine 9(2): 159-170.

- Guthrie SO, Gordon PV, Thomas V, Thorp JA, Peabody J, et al. (2003) Necrotizing enterocolitis among neonates in the United States. Journal of perinatology 23(4): 278-285.

- Ahle M, Drott P, Elfvin A, Andersson RE (2018) Maternal, fetal and perinatal factors associated with necrotizing enterocolitis in Sweden. A national case-control study. PLoS One 13(3): 145-156.

- Suply E, Leclair MD, Neunlist M, Roze JC, Flamant C, et al. (2015) Spontaneous intestinal perforation and necrotizing enterocolitis: a 16-year retrospective study from a single center. European Journal of Pediatric Surgery 25(6): 520-525.

- Cotten CM, Taylor S, Stoll B, Goldberg RN, Hansen NI, et al. (2009) Prolonged duration of initial empirical antibiotic treatment is associated with increased rates of necrotizing enterocolitis and death for extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 123(1): 58-66.

- Fogart M, Osborn DA, Askie L, Seidler AL, Hunter K, et al. (2018) Delayed vs early umbilical cord clamping for preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 218(1): 1-18.

- Lee Jy, Park KH, Kim A, Yang HR, Jung EY, et al. (2017) Maternal and placental risk factors for developing necrotizing enterocolitis in very preterm infants. Pediatrics & Neonatology 58(1): 57-62.

- Barrington KJ (1999) Umbilical artery catheters in the newborn: effects of position of the catheter tip. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1(1): 12-34.

- Dollberg S, Lusky A, Reichman B (2005) Patent ductus arteriosus, indomethacin and necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants: a population-based study. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition 40(2): 184-188.

- Mitra S, Florez ID, Tamayo ME, Mbuagbaw L, Vanniyashingam T, et al. (2018) Association of placebo, indomethacin, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen with closure of hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama 319(12): 1221-1238.

- Patel RM, Underwood MA (2018) Probiotics and necrotizing enterocolitis. Seminars in pediatric surgery 27(1): 39-46.

- Pammi M, Cope J, Tarr PI, Warner BB, Morrow AL, et al. (2017) Intestinal dysbiosis in preterm infants preceding necrotizing enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Microbiome 5(1): 1-15.

- Patel RM, Knezevic A, Shenvi N, Hinkes M, Keene S, et al. (2016) Association of red blood cell transfusion, anemia, and necrotizing enterocolitis in very low-birth-weight infants. Jama 315(9): 889-897.

- Whyte R, Kirpalani H (2011) Low versus high haemoglobin concentration threshold for blood transfusion for preventing morbidity and mortality in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11(1): 1-15.

- Hay S, Zupancic JA, Flannery DD, Kirpalani H, Dukhovny D (2017) Should we believe in transfusion-associated enterocolitis? Applying a GRADE to the literature. Seminars in perinatology 41(1): 80-91.

- Lucas A, Cole TJ (1990) Breast milk and neonatal necrotising enterocolitis. The Lancet 336(8730): 1519-1523.

- Quigley M, McGuire W (2014) Formula versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of systematic reviews 6(7): 24-36.

- O'Connor DL, Gibbins S, Kiss A, Bando N, Brennan-Donnan EN, et al. (2016) Effect of supplemental donor human milk compared with preterm formula on neurodevelopment of very low-birth-weight infants at 18 months: a randomized clinical trial. Jama 316(18): 1897-1905.

- Morgan J, Young L, McGuire W (2014) Delayed introduction of progressive enteral feeds to prevent necrotising enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 12(1): 20-42.

-

Nusrat Khan*, Ahmed Elhidadi, Uzma Afzal, Amal Yahyi, Mohammad Farah Osman, Ela Bayuni, Aiman Rahmani and Hassib Narchi. Risk factors for Necrotizing Enterocolitis in Very Preterm Infants- A Retrospective Observational Case-Control study. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 5(3): 2024. GJPNC.MS.ID.000611.

NEC, Risk factors, (Antenatal, natal, postnatal), Very preterm, NICU, Blood transfusion, EOS, Clinical sepsis, Statistical significance

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.