Research article

Research article

Assessment of Knowledge on The Use of Adrenaline Autoinjectors in A Paediatric Portuguese Population

Rita Lages Pereira1*, Francisca Gomes1, Maria Beatriz Guimarães2, Fábia Ginja de Carvalho1, Margarida Reis Morais1, Sofia Miranda1 and Ivo Miguel Neves1

1Pediatrics Department, Unidade Local de Saúde de Braga, Portugal

2School of Medicine of the University of Minho, Portugal

Rita Lages Pereira, Pediatrics department, Unidade Local de Saúde de Braga, Portugal, Unidade Local de Saúde de Braga, Braga, Portugal

Received Date:January 01, 2025; Published Date:January 15, 2025

Abstract

Objective: To assess the knowledge and confidence of parents and patients regarding the use of adrenaline autoinjectors.

Methods: A cross-sectional, observational study was conducted, including 53 patients with food allergies and prescribed adrenaline

autoinjectors, who were seen in Pediatric Allergy consultations between January 2022 and February 2024. Demographic and clinical data were

collected, and telephone interviews were conducted with parents and patients aged 5 years or older.

Results: Among the 53 patients, 52.8% were male, and 50.9% were aged 1 to 4 years. One patient did not own an autoinjector, while 88.7% had

at least two adrenaline autoinjectors. However, 28.3% did not carry any autoinjector, and only 1.9% consistently carried two. At school, 32.1% of

the patients did not have their autoinjectors. Proper storage was reported by 96.2% of parents, but only 18.9% replaced the device when precipitate

appeared in the viewing window. Regarding administration, only 7.5% of parents mentioned all the steps, and no patient was able to do so. Only

20.8% of parents indicated they would administer a second autoinjector if symptoms persisted. The majority of parents (81.1%) and patients

(61.5%) felt capable of administering adrenaline autoinjectors, yet 50.9% and 38.5%, respectively, felt apprehensive about its use.

Conclusion: Significant gaps in knowledge and confidence regarding the use of adrenaline autoinjectors were identified among parents and

pediatric patients. Educational and psychological interventions are necessary to empower families and ensure effective management of anaphylaxis

in children.

Keywords:Anaphylaxis; Food Allergy; Adrenaline Autoinjectors

Abbreviations:EMA: European Medicines Agency; Mdn: Median; IQR: Interquartile Range

Introduction

Anaphylaxis is a serious systemic hypersensitivity reaction, potentially life-threatening, which occurs rapidly after exposure to an allergen. This medical emergency requires early identification and prompt treatment, which can be lifesaving [1,2].

The prevalence and incidence of anaphylaxis is difficult to estimate, since this condition is frequently underdiagnosed or not adequately reported. Among children, the global estimated prevalence is increasing, currently ranging between 0.04% and 1.8%. In Europe, the incidence ranges from 2.3 to 761 cases per 100,000 person years [3]. Anaphylaxis may be triggered by ingestion, injection, inhalation, or contact with an allergen, and exacerbated by cofactors such as physical exercise, emotional stress, changes in daily routine (such as travel), premenstrual period, infections, and medications like nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [1,2,4,5] Food allergens are the leading cause of anaphylaxis in children [5-9].

According to diagnostic criteria defined by the World Allergy

Organization, anaphylaxis is highly likely when at least one of the

following clinical criteria is met:

A. Acute onset of illness (minutes to several hours) with

involvement of skin and/or mucosal tissues (eg, generalized hives,

pruritus or flushing, swollen lips/tongue/uvula), and at least one of

the following:

1. Respiratory compromise (eg, dyspnea, wheezing, stridor,

reduced peak expiratory flow, hypoxemia);

2. Reduced blood pressure or symptoms of end-organ

dysfunction (eg, hypotonia, syncope, incontinence);

3. Severe gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, severe crampy

abdominal pain, repetitive vomiting), especially after exposure

to non-food allergens.

B. Acute onset of hypotension, bronchospasm or laryngeal

symptoms after exposure to a known or highly probable allergen

for that patient (minutes to several hours), even in the absence of

skin involvement [1].

The diagnosis of anaphylaxis can be supported by determining serum tryptase levels 30 minutes to 2 hours after the reaction onset, followed by a repeat measurement at least 24 hours after complete symptom resolution (baseline tryptase) [1,2,6]. Intramuscular adrenaline is the first-line treatment for an anaphylactic reaction and should be administered as early as possible to reduce associated morbidity and mortality [1,2]. The initial recommended dose is 0.01 mg/kg (maximum dose of 0.5 mg above 40 kg or 0.3 mg under 12 years or below 40 kg) at a 1:1000 dilution (1 mg/ mL), and it can be repeated every 5 minutes if symptoms persist [6] Portable adrenaline autoinjectors enable treatment immediately upon symptom recognition [2,6] The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recommends prescribing two autoinjectors for any at-risk patient, who should carry them at all times [10]. In Portugal, the available adrenaline autoinjectors are Epipen® and Anapen®, with doses of 0.15mg/0.3mL and 0.3mg/0.3mL [11]. Additionally, it is crucial to provide an individualized anaphylaxis management plan for the patient and caregivers, detailing warning signs, necessary medications, and instructions for proper autoinjector use [1, 2].

A Portuguese study conducted between 2007 and 2017, which evaluated 533 pediatric patients with anaphylaxis, showed that 78% had an adrenaline autoinjector prescribed, but only 12% of those used it successfully [8]. Identified obstacles for autoinjector underuse include caregivers’ inability to recognize reaction severity, fear of administration, uncertainty about whether it was necessary, and unavailability of an autoinjector [6,12,13]. Thus, the effectiveness of anaphylaxis treatment relies on patients’ and caregivers’ ability to recognize reaction signs and correctly administer adrenaline [2]. Previous studies indicate that many parents and patients do not feel sufficiently empowered or confident to use autoinjectors, which may delay treatment [12-15]. This study aims to evaluate the knowledge and practices of parents and pediatric patients in using adrenaline autoinjectors, identifying areas of difficulty and opportunities for educational improvement.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional observational study was conducted involving patients aged 1-17 years diagnosed with food allergies and prescribed an adrenaline autoinjector. Participants were selected from the pool of patients followed at the Paediatric Allergy Consultation at Braga’s Local Health Unit between January 2022 and February 2024. A total of 60 patients met the inclusion criteria and were invited by e-mail to enroll in the study for a telephone interview. Of these, five were excluded due to loss of follow-up, one due to refusal to participate, and one due to inability to contact, resulting in a final sample of 53 patients.

Demographic and clinical data for each patient were collected from electronic medical records. Telephone interviews were conducted with one of the parents and with the patients if they were aged 5 years or older. The interviews assessed knowledge of administration steps, storage practices, and confidence in using the device.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from the parent and the patients if they were over five years of age. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Research in Life and Health Sciences of the University of Minho with the identification number 057/2024, and by the Ethics Committee of the Local Health Unit of Braga with identification number 73_024. Data confidentiality was ensured and maintained throughout the project.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics (International Business Machine, Statistical Package for the Social Sciences), version 26.0. The normality of quantitative variable distributions was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests, in addition to analyzing asymmetry, kurtosis, and graphical distributions. Quantitative variables did not meet normality assumptions and were reported as the median (Mdn) and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical variables were described using absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies.

Results and Discussion

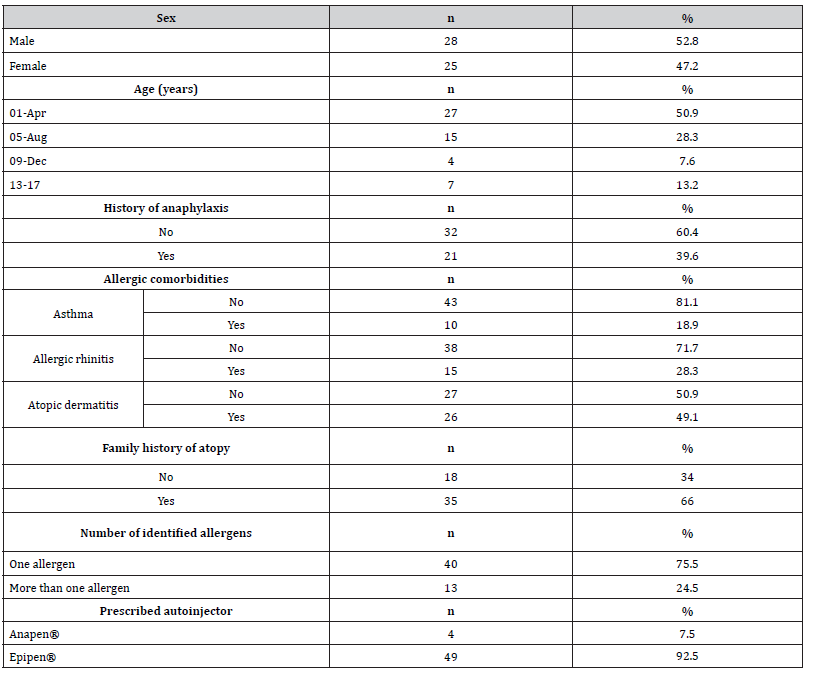

A total of 53 patients with food allergy and an adrenaline autoinjector prescription were included in the study, of whom 52.8% (n=28) were male. The median age was 4 years (IQR 6 years), with approximately half of the sample (n=27, 50.9%) aged between 1 and 4 years. The most common allergic comorbidity was atopic dermatitis, present in 49.1% (n=26) of the patients. Regarding food allergens, about a quarter of the patients showed an allergy to more than one food item. Most patients (n=32, 60.4%) had no history of anaphylaxis, and the Epipen® was the most prescribed autoinjector, given to 92.5% (n=49) of the patients. The complete sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are provided in Table 1.

Table 1:Sociodemographic characterization of the study sample.

n – absolute frequencies; % – relative frequencies

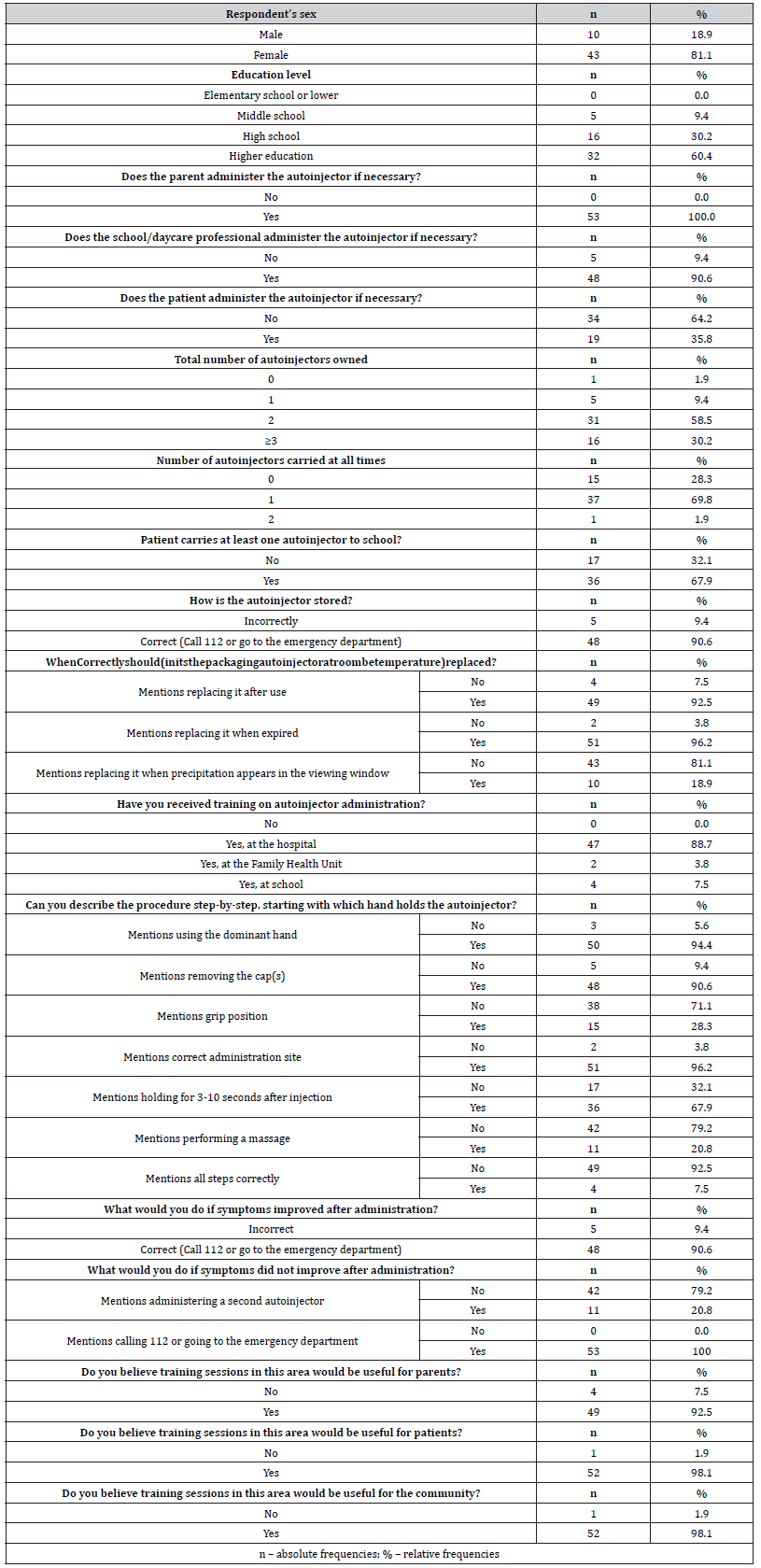

Telephone interviews with the parents

Telephone interviews were conducted with one parent of each patient in the sample (n=53). Most interviewees (n=43, 81.1%) were female, and 60.4% (n=32) held a higher education degree. It was found that 90.6% (n=48) believed the school or nursery would be prepared to administer the adrenaline autoinjector in the event of anaphylaxis, while 35.8% (n=19) of the patients would be able to self-administer, corresponding to 73.1% (n=19) of patients aged 5 years or older (n=26).

In this study sample, 1.9% (n=1) of patients had no autoinjector (prescribed, but not purchased), 28.3% (n=15) did not carry it with them, and only 1.9% (n=1) always carried two autoinjectors. At school, 32.1% (n=17) of the patients did not have any adrenaline autoinjector available. Regarding parental knowledge, 96.2% (n=51) reported proper storage of the autoinjector. For replacement, 96.2% (n=51) reported changing the device when the expiration date passed, 92.5% (n=49) after use, but only 18.9% (n=10) cited replacing it when precipitate appeared in the viewing window.

All parents received training on how to administer the autoinjector, mostly (n=47, 88.7%) at the hospital. For the administration procedure, the least frequently mentioned steps were massaging after injection (n=11, 20.8%), the grip position (n=15, 28.3%) and waiting 3-10 seconds after injection (n=36, 67.9%). Only 7.5% (n=4) of the parents correctly mentioned all steps. Regarding actions to take if the patient’s symptoms improved after adrenaline administration, most parents (n=48, 90.6%) answered correctly. However, when asked what they would do if symptoms did not improve, only 20.8% (n=11) indicated they would administer a second dose. Most parents found training sessions helpful for parents (n=49, 92.5%), patients (n=52, 98.1%), and the general community (n=52, 98.1%). Detailed interview results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2:Results of parent responses regarding sociodemographic data, knowledge, and training related to adrenaline autoinjectors.

a Variable created from the answers to the interview question in which it is included

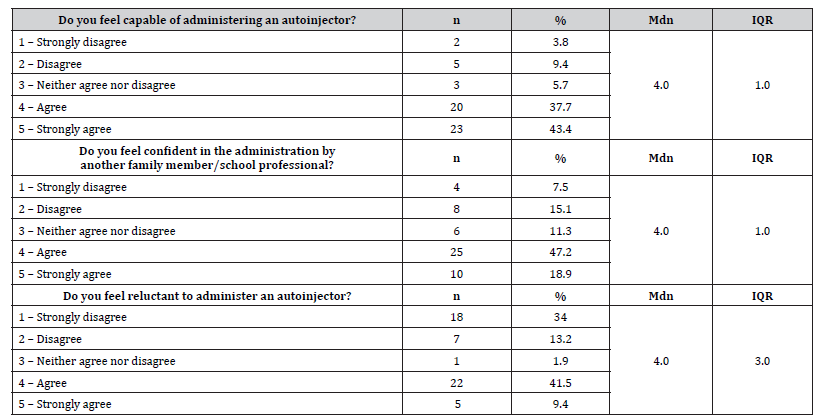

The interview also included questions on parental confidence and anxiety regarding the administration of the adrenaline autoinjector. Regarding these questions, 81.1% (n=43) of interviewees felt capable of administering the autoinjector, and 66.1% (n=35) felt confident about administration by another family member or a school/nursery staff member. However, 50.9% (n=27) reported feeling apprehensive or reluctant about this procedure. All these findings are presented in Table 3.

Table 3:Results of parent responses on confidence and reluctance in administering an adrenaline autoinjector.

n – absolute frequencies; % – relative frequencies; Mdn – median; IQR – interquartile range

Telephone interviews with patients

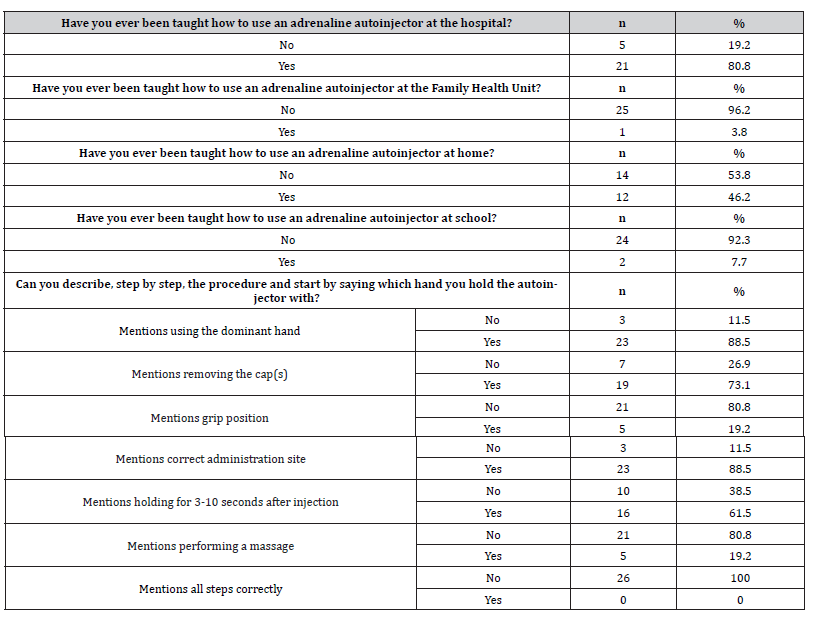

Additionally, 26 pediatric patients aged 5 years or older were interviewed. Most patients (n=21, 80.8%) reported receiving instruction on using the adrenaline autoinjector in the hospital, and 46.2% (n=12) at home. Regarding the administration procedure description, the least mentioned steps were massaging after injection (n=5, 19.2%), grip position (n=5, 19.2%) and waiting 3-10 seconds after injection (n=16, 61.5%). Furthermore, none of the patients mentioned all the administration steps. These results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4:Results of patient responses on training and knowledge regarding adrenaline autoinjectors.

n – absolute frequencies; % – relative frequencies

Variable created from the answers to the interview question in which it is included

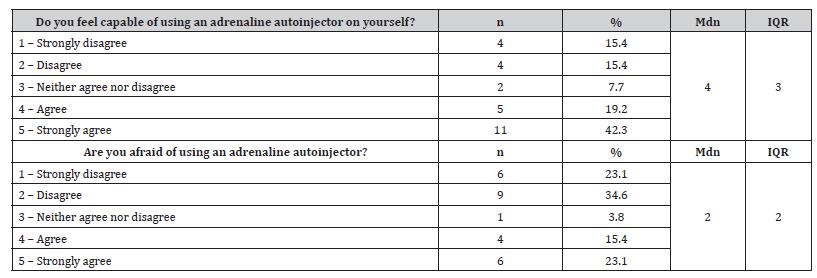

During patient interviews, questions were also asked about confidence and fear in using the adrenaline autoinjector. Most (n=16, 61.5%) patients reported feeling capable of self-administering an adrenaline autoinjector, while 38.5% (n=10) admitted feeling afraid. These results are presented in Table 5.

Table 5:Results of patient responses on confidence and reluctance in administering an adrenaline autoinjector.

n – absolute frequencies; % – relative frequencies; Mdn – median; IQR – interquartile range

Discussion

In the study sample, most patients (60.4%) had no prior history of anaphylaxis. According to current recommendations, an adrenaline autoinjector should be prescribed to all patients with a history of anaphylaxis or at high risk of severe allergic reactions, justifying the large percentage of patients with a prescribed autoinjector without a prior history of anaphylaxis [1,2,16-18].

The results revealed important information regarding adrenaline autoinjector usage, notably the low adherence to always carrying it, with 28.3% reporting that they did not always carry it with them. Furthermore, although 88.7% of patients had at least two autoinjectors, only 1.9% always carried both, as recommended by the EMA [2]. Other studies in the literature report similar findings. A study conducted in Spain reported that, despite all patients having at least one adrenaline autoinjector, 40.6% did not always carry it with them [15]. Another study in Turkey found that only 21.6% of patients had two adrenaline autoinjectors [14]. In a study conducted in the United States, among patients who had two autoinjectors, only 18% always carried both [19]. Early administration of adrenaline is crucial in the treatment of an anaphylactic reaction, and literature suggests that a second autoinjector dose is necessary in 16% to 36% of patients with anaphylaxis. Thus, both the absence of an autoinjector and the lack of a second one increase the risk of morbidity and mortality associated with anaphylaxis [19,20].

Additionally, although 90.6% of parents believed that the daycare/school would be prepared to administer the autoinjector if necessary, 32.1% of patients did not have any adrenaline autoinjector available in these places. Considering the number of hours that children/adolescents spend in these settings, it is essential to have an autoinjector in a pre-defined and easily accessible location for emergencies.

Beyond the availability of adrenaline autoinjectors, ensuring that devices are always in ideal working condition is critical. Knowledge of proper storage and timely replacement of the autoinjector is essential [21]. In this study, most parents reported correct storage (96.2%) and proper replacement of the autoinjector, particularly when it expires (96.2%) or after use (92.5%). Similarly, in the Turkish study, 88.9% of participants reported proper storage of the autoinjector, and 89.5% replaced it under these two circumstances [14]. However, in the present study, only 18.9% mentioned the need to replace the autoinjector if there was precipitate in the viewing window, suggesting that this information may not be communicated or understood correctly by parents, risking the use of adrenaline that is no longer in ideal condition.

Correct administration of the adrenaline autoinjector is crucial for the effectiveness of anaphylaxis treatment. The Spanish study, observing participants’ administration on a practice model, demonstrated that only 13% performed all the administration steps correctly, with the most commonly omitted step being massage after injection [15]. In this study, the assessment of autoinjector administration was conducted through verbal descriptions of the steps. Only 7.5% of parents mentioned all steps correctly, and none of the patients did so. Massage after injection, the holding position, and waiting 3–10 seconds after injection were the most frequently forgotten steps by both parents and patients. These findings highlight significant gaps in autoinjector administration, indicating an evident need to reinforce practical training on autoinjector usage for patients and caregivers.

After administering an adrenaline autoinjector, parents must know what actions to take. After using adrenaline, regardless of circumstances, the patient must be evaluated by a physician and remain under observation for a few hours due to the risk of a biphasic reaction, a potentially more severe second anaphylactic reaction. Furthermore, if symptoms persist, a second adrenaline autoinjector should be administered 5 to 15 minutes after the first administration [2]. In this study, all parents reported taking the patient to an emergency service or calling the emergency number if symptoms did not improve. However, 9.4% would not do so if symptoms improved. The Turkish study reported that 98.4% of participants would go to the emergency room immediately after using an adrenaline autoinjector, without distinguishing between cases in which symptoms improved or not [14]. By making this distinction, the present study identified parents who were unaware that the patient should be seen by a doctor after using the autoinjector, even if symptoms improved. On the other hand, only 20.8% of parents reported administering a second adrenaline autoinjector if symptoms did not improve, reflecting, once again, the risk of patients needing a second autoinjector but not receiving it due to lack of one. This finding may also help explain why many patients do not carry a second autoinjector with them.

These results emphasize the need to constantly remind patients at every consultation about the recommendations on carrying, maintaining, and using the adrenaline autoinjector to optimize treatment and improve prognosis in cases of anaphylaxis. Additionally, to ensure correct administration of adrenaline, it is essential to invest in training and practical drills on how to use the device.

Using an adrenaline autoinjector often involves a significant psychological burden, as the need to be constantly prepared for an emergency creates anxiety and stress among patients and their caregivers. Studies show that the psychological stress faced by parents has been underestimated, as it affects the success of training and decision-making in emergencies [14,22,23]. Additionally, literature suggests that fear may be an important factor in underuse of adrenaline autoinjectors [14,22]. Accordingly, this study assessed parents’ and patients’ perception of confidence in using the adrenaline autoinjector. Results showed that most parents (81.1%) felt capable of administering it and confident in having it administered by another family member or school staff (66.1%). However, 13.2% did not feel as capable, and about half of the parents (50.9%) felt apprehensive about administering the autoinjector. Regarding the patients, while most (61.5%) felt competent in administering an adrenaline autoinjector, a significant number (30.8%) did not feel capable, and 38.5% felt fear in using it. These data suggest that, as described in the literature, emotional and psychological factors may influence and even delay the necessary intervention in anaphylaxis [12,14]. Therefore, it is essential to invest in psychological support for patients and their caregivers to better manage the anxiety and fear associated with emergencies in which they may need to intervene. Moreover, investing in knowledge and practical simulations can help them feel more prepared to act effectively if necessary. Furthermore, in June 2024, the EMA recommended granting authorization for the introduction of the first intranasal adrenaline in the European Union, which could represent a significant paradigm shift for parents and patients who feel fear/apprehension about administering intramuscular adrenaline, thereby improving therapeutic adherence [24].

When interpreting the results, it is important to acknowledge the study’s limitations, including the small sample size and its single-center design, making it difficult to draw conclusions on a population level. Additionally, the objectivity of the study could have been enhanced through in-person interviews and the use of simulation models to assess autoinjector skills, rather than relying solely on descriptions of usage steps. Responses to questions regarding confidence or reluctance in autoinjector use might also have been influenced by social desirability bias.

Despite these limitations, the study offers significant value by providing insights into patients’ and parents’ knowledge of adrenaline autoinjector use, as well as the psychological factors involved. These findings underscore critical areas for intervention and education to improve outcomes.

Conclusion

In summary, although parents and patients demonstrated a general satisfactory level of knowledge about adrenaline autoinjector usage, there are several areas for improvement, particularly in proper procedure execution, autoinjector carriage, and confidence in administration. Thus, it is essential to invest in continuous training and education for parents and patients. Educational sessions should be implemented to address key gaps identified and provide hands-on training in autoinjector administration under medical guidance. A prospective study could then evaluate knowledge progress after training sessions. Beyond hospital-based education, audiovisual tools such as training videos can be made available, and training sessions should be promoted in familiar and school environments. Empowering educational institutions, where children spend a large portion of time, should be a priority, given the potential risk of anaphylaxis episodes during school hours. Additionally, parents’ and patients’ apprehension and lack of confidence in using the adrenaline autoinjector could impact decision-making in emergencies. Therefore, psychological support should also be prioritized through psychology consultations, needle-phobia desensitization therapy, and experience-sharing groups, among other strategies. This study underscores the critical role of education and psychological support in improving the use of adrenaline autoinjectors among pediatric patients and their families, paving the way for safer anaphylaxis management.

Acknowledgement

The authors have no additional individuals to acknowledge.

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Cardona V, Ansotegui IJ, Ebisawa M, Yehia El-Gamal, Montserrat Fernandez Rivas, et al. (2020) World allergy organization anaphylaxis guidance 2020. World Allergy Organ J 13(10): 100472.

- Muraro A, Worm M, Alviani C, Victoria C, Audrey DG, et al. (2022) EAACI guidelines: Anaphylaxis (2021 update). Allergy 77(2): 357-377.

- Wang Y, Allen KJ, Suaini NHA, McWilliam V, Peters RL, et al. (2019) The global incidence and prevalence of anaphylaxis in children in the general population: A systematic review. Allergy 74(6): 1063-1080.

- Tarczoń I, Cichocka Jarosz E, Knapp A, Kwinta P (2022) The 2020 update on anaphylaxis in paediatric population. Postepy Dermatol Alergol 39(1): 13-19.

- Anagnostou K (2018) Anaphylaxis in Children: Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Management. Curr Pediatr Rev 14(3): 180-186.

- Mota I, Pereira AM, Pereira C, Elza Tomaz, Manuel Branco Ferreira, et al. (2015) Abordagem e Registo da Anafilaxia em Portugal [Approach and Registry of Anaphylaxis in Portugal]. Acta Med Port 28(6): 786-796.

- Gaspar Â, Santos N, Faria E (2019) Anafilaxia em Portugal: 10 anos de Registo Nacional da SPAIC 2007-2017. Rev Port Imunoalergologia 27(4): 289-307.

- Gaspar Â, Santos N, Faria E, Ana Margarida Pereira, Eva Gomes, et al. (2021) Anaphylaxis in children and adolescents: The Portuguese Anaphylaxis Registry. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 32(6): 1278-1286.

- Grabenhenrich LB, Dölle S, Moneret-Vautrin A, Alice Köhli, Lars Lange, et al. (2016) Anaphylaxis in children and adolescents: The European Anaphylaxis Registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol 137(4): 1128-1137.e1.

- European Medicines Agency. Better training tools to support patients using adrenaline auto-injectors [Internet]. 2015 Aug.

- Carneiro-Leão L, Santos N, Gaspar  (2018) Anafilaxia na comunidade - Materiais educacionais. Rev Port Imunoalergologia 2(26): 121-126.

- Narchi H, Elghoudi A, Al Dhaheri K (2022) Barriers and challenges affecting parents' use of adrenaline auto-injector in children with anaphylaxis. World J Clin Pediatr 11(2): 151-159.

- Glassberg B, Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Wang J (2021) Factors contributing to underuse of epinephrine autoinjectors in pediatric patients with food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 126(2): 175-179.e3.

- Esenboga S, Kahveci M, Cetinkaya PG, U M Sahiner, O Soyer, et al. (2020) Physicians prescribe adrenaline autoinjectors, do parents use them when needed? Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 48(1): 3-7.

- Hernández PV, García MG, García AR (2022) Uso de Autoinyectores de Adrenalina en pacientes con Anafilaxia. XLVI Congr SEICAP pp. 185.

- Gold MS, Sainsbury R (2000) First aid anaphylaxis management in children who were prescribed an epinephrine autoinjector device (EpiPen). J Allergy Clin Immunol 106(1 Pt 1): 171-176.

- Simons FER (2004) First-aid treatment of anaphylaxis to food: Focus on epinephrine. J Allergy Clin Immunol 113(5): 837-844.

- Sicherer SH, Forman JA, Noone SA (2000) Use assessment of self-administered epinephrine among food-allergic children and pediatricians. Pediatrics 105(2): 359-362.

- Song TT, Brown D, Karjalainen M, Lehnigk U, Lieberman P (2018) Value of a Second Dose of Epinephrine During Anaphylaxis: A Patient/Caregiver Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 6(5): 1559-1567.

- Kemp SF, Lockey RF, Simons FE (2008) Epinephrine: the drug of choice for anaphylaxis - A statement of the World Allergy Organization. Allergy 63(8): 1061-1070.

- Simons FER, Peterson S, Black CD (2002) Epinephrine dispensing patterns for an out-of-hospital population: A novel approach to studying the epidemiology of anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 110(4): 647-651.

- Kim JS, Sinacore JM, Pongraci JA (2005) Parental use of EpiPen for children with food allergies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 116(1): 164-168.

- Knibb R, Halsey M, James P, du Toit G, Young J (2019) Psychological services for food allergy: The unmet need for patients and families in the United Kingdom. Clin Exp Allergy 49(11): 1390-1394.

- First nasal adrenaline spray for emergency treatment against allergic reactions [Internet]. European Medicines Agency; July 2024.

-

Rita Lages Pereira*, Francisca Gomes, Maria Beatriz Guimarães, Fábia Ginja de Carvalho, Margarida Reis Morais, Sofia Miranda and Ivo Miguel Neves.Assessment of Knowledge on The Use of Adrenaline Autoinjectors in A Paediatric Portuguese Population. Glob J of Ped & Neonatol Car. 5(3): 2025. GJPNC.MS.ID.000612.

Anaphylaxis, Food Allergy, Adrenaline Autoinjectors, Children, Physical exercise, World Allergy Organization, Anapen®, Epipen®, Autoinjector

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.