Research Article

Research Article

Reconstruction and/or Repair of The Multi-Ligament Knee Injury: A Systematic Review

David S Constantinescu1*, Eric Curtis2, James R Satalich 3 and Alexander R Vap4

1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Miami, USA

2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of California San Francisco, USA

3,4Department of Orthopedic Surgery, VCU Medical Center, USA

David S Constantinescu, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, University of Miami, USA.

Received Date: March 23, 2021; Published Date: April 08, 2021

Abstract

Background: A paucity of data exists regarding the comparison of outcome scores following multiple ligament knee injury (MLKI) reconstruction/repair methods.

Purpose: The purpose of this study was to conduct a systematic review of the literature on patient outcomes following reconstruction and/or repair of the MLKI.

Study Design: Systematic review of level IV studies

Methods: This review study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement. Pubmed and Cochrane were analyzed using the following search strategy: “(((multi ligament knee injury) OR multiple ligament knee injury) AND reconstruction) AND repair”. Inclusion criteria for articles were as follows: 1) human subjects 2) follow up of at least mean 12 months 3) outcome studies following surgical ligament reconstruction and/or repair after multiple ligament knee injury 4) reported objective outcome data on respective patient cohorts. The exclusion criteria included: case reports, technique papers, and articles without paired pre and post-operative objective findings.

Result: 109 studies were initially retrieved, with 7 satisfying all inclusion criteria. The review included a total of 183 patients; 126 males and 57 females. The average age was 36.3 (29.6-45.3). The 7 studies included ligamentous reconstruction, repair and reconstruction/repair techniques via a one-stage and two-staged method. The weighted mean Lysholm scores significantly improved from 30.3 +/- 4.2 preoperatively to 86.2 +/- 5.6 post-operatively (paired t-test; p<0.001).

Conclusion: A review of the current literature concludes that surgical ligamentous repair and/or reconstruction of the MLKI yields a significant improvement from pre-operative to post-operative Lysholm scores. This suggests that surgical intervention provides benefit to patients in this population. Other outcome scores have insufficient data to conduct a statistical analysis.

Keywords: Multiple ligament knee injury; Multiple knee ligament reconstruction; Multiple knee ligament repair; Knee ligament

Abbreviations: MLKI-multiple-ligament knee injury

Introduction

A multiple-ligament knee injury (MLKI) is a devastating injury most commonly due to an acute knee dislocation [1-3]. This high energy injury leads to disruption of the major stabilizing ligaments. Sequela of these injuries included compromised knee stability and pain [4]. The goal of surgical intervention is to restore the ligamentous stability of the knee by either repair, reconstruction, or a combination of both reconstruction and repair. The incidence of knee dislocations has been reported in 0.072% of all musculoskeletal trauma [5]. Although not common, they are a devastating injury. As such, limited research exists quantifying outcomes as a result of surgical repair.

The purpose of this study was to systematically review reported knee outcome measures among MLKI reconstructions and/or repairs that specifically compared pre-operative and postoperative scores. Furthermore, the surgical technique and number of surgeries performed was categorized in an attempt to observe any difference in outcomes. This included comparing whether ligamentous tissue was reconstructed, repaired or both as well as comparing whether the procedures were done in one stage vs two stage. The hypothesis was that MLKI reconstruction and/or repair would result in statistically significant improvement in outcome scores.

Materials and Methods

Article identification and selection

This study was conducted in accordance with the 2009 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis (PRISMA) statement. A systematic review of the literature regarding the existing evidence for MLKI reconstruction and/or repair outcomes was performed using the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed (1980-present), and MEDLINE (1980-present). The queries were performed in May 2018.

The literature search strategy included the following search: “(((multi ligament knee injury) OR multiple ligament knee injury) AND reconstruction) AND repair”. Inclusion criteria for articles were as follows:

• Human subjects.

• Follow up of at least mean 12 months.

• Outcome studies following surgical ligament reconstruction and/or repair after multiple ligament knee injury.

• Reported objective outcome data on respective patient cohorts. The exclusion criteria included: case reports, technique papers, and articles without paired pre and post-operative objective findings.

All references within included studies were cross-referenced for inclusion if missed by the initial search. If a duplicate study population was encountered, the manuscript with the longer mean follow-up was included to avoid overlap. Two investigators independently reviewed the abstracts from all identified articles. Full-text articles were obtained for review if necessary, to allow further assessment of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Additionally, all references from the included studies were reviewed and reconciled to verify that no relevant articles were missing from the systematic review.

Bias

Studies classified as level of 4 can potentially be affected by selection and performance bias because of the lack of randomization and prospective comparative control groups especially in populations characterized by heterogeneity of injuries. Selected studies were reviewed for potential bias while recognizing the constraints present with such studies. Due to the anticipated heterogeneity, the results were presented individually. As such, a meta-analysis was contra-indicated. Reported outcome scores for the knee include Lysholm, International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC), Tegner, or Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). In our review, the only outcome score that was consistently reported was Lysholm. In an attempt to quantitatively synthesize data, only studies using the same outcome score (Lysholm) with included preoperative and postoperative scores and standard deviations were used.

Data Collection

The information was collected from the included studies. Patient demographics, follow-up, and objective outcomes were extracted and recorded. For continuous variables (eg, age, timing, follow-up, outcome scores), the mean was collected if reported. Data were recorded into a custom Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corp) using a modified information extraction table.

Result

Study selection

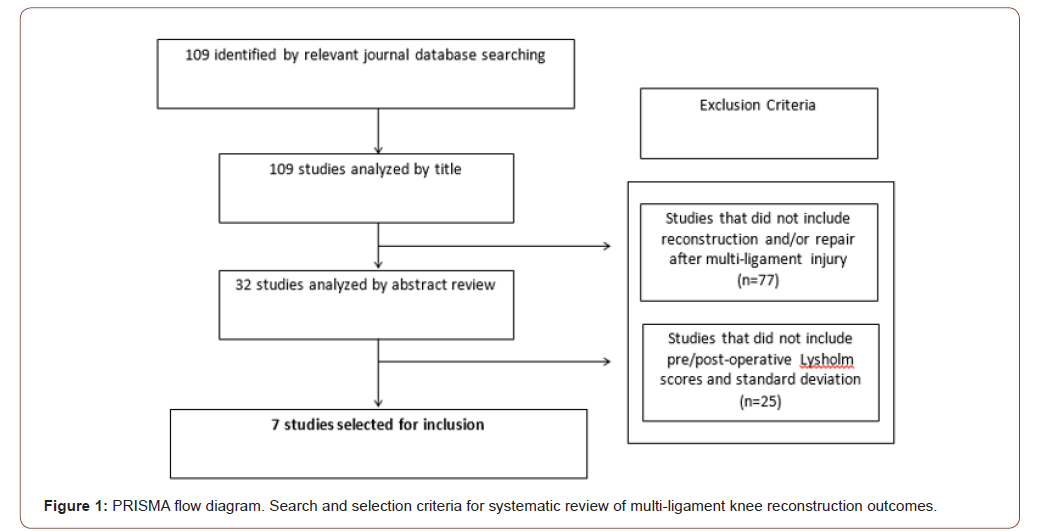

The systematic search performed using the above-mentioned keywords and phrases identified seven studies, after removing duplicates and applying exclusion criteria (cite included studies). One hundred and nine studies were initially retrieved, with 7 satisfying all inclusion criteria [7-12]. There were no additional articles from the Cochrane database. Each article was first screened by title leaving 32 articles. Excluded via title screen were articles that did not include reconstruction and/or repair after multiligament injury. The remaining articles were then screened by abstract and if necessary, full text, yielding seven articles that were included in the review. All seven studies included were case series that included pre/post-operative Lysholm scores with a standard deviation. (Figure 1) is a PRISMA flowchart that demonstrates selection criteria of the systematic review. Following review of all references from the included studies, no additional studies met inclusion criteria.

Demographics

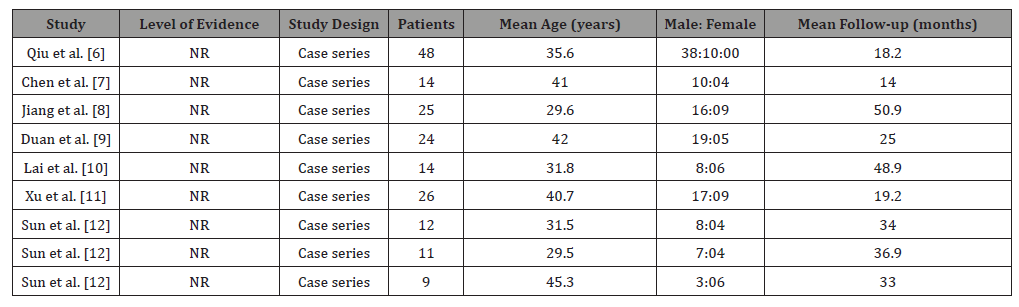

The review included a total of 183 patients; 126 males and 57 females. The average age was 36.3 (29.6-45.3). The mean follow up was 30.8 months (14-50.9). Demographics of each included study are reported in Table 1.

Injured tissues, surgical techniques and outcomes

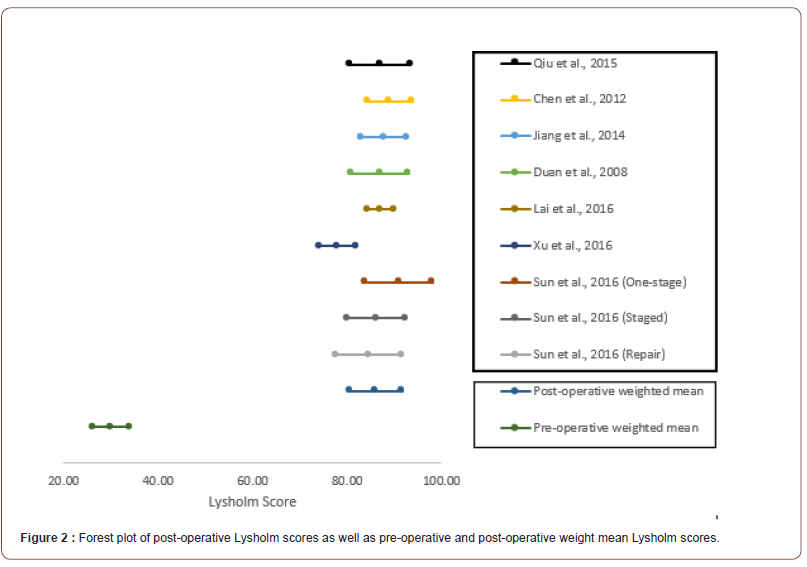

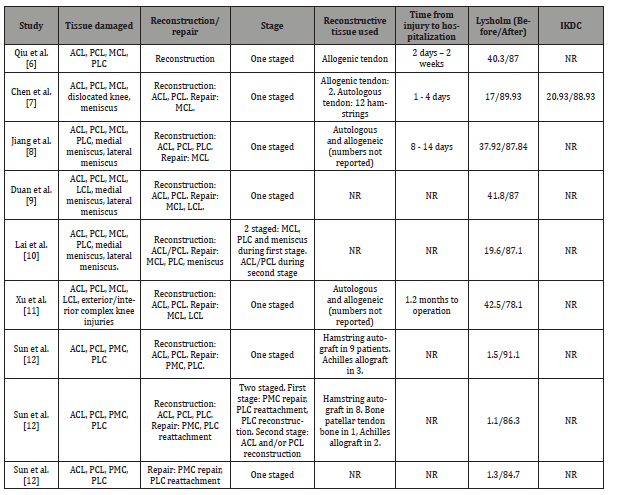

Injured knee ligaments were specified and are detailed in Table 2. The 7 studies included ligamentous reconstruction, repair and reconstruction/repair techniques via a one-stage and staged method. Sun et al reported separate outcomes among 3 different cohorts (1 stage reconstruction, 2 stage reconstruction, repair) and was therefore included as 3 different cohorts in (Table 2) [12]. When breaking up Sun et al study, a total of nine cohorts of data were identified. One of nine cohorts used only reconstruction [6], 7 of nine cohorts used a combination of reconstruction and repair [7-12], and one of nine cohorts used only repair [12]. Seven of nine cohorts used a one stage surgical approach where reconstruction and repair was performed during the same procedure [6-9,11,12]. Two of nine cohorts used a two-stage surgical approach where anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) were reconstructed during a second surgery [10,12]. Lysholm outcome scoring was reported by all studies and included pre-operative and post-operative standard deviations. Postoperative Lysholm scores from all studies were at the last date of follow up. Pre-operative weighted mean Lysholm Score among all included studies was 30.3 +/- 4.2. Post-operative weighted mean Lysholm Score was 86.2 +/- 5.6. These results indicate a statistically significant improvement in Lysholm scores after multi-ligament reconstruction and/or repair (Paired t-test; p<0.001).

Complications and revision surgery

No complications as a result of surgery were able to be ascertained. However, Xu et al noted that nine of 26 patients required a second surgery for a missed diagnosis of PCL injury (11).6.5

Level of evidence

Overall, the current level of evidence on outcomes after multi ligament reconstruction and/or repair tears in the MLKI is poor. Of the 7 studies analyzed, all were case series and as such would be considered level IV evidence.

Discussion

The most important finding of this study is that MLKI reconstruction and/or repair yields improvement in Lysholm outcome scoring. Surgical intervention to regain knee stability has potential risks. However, this study demonstrates that functional outcomes measured by Lysholm scoring improve following surgery. The management of MLKI remains controversial [1-3]. Certain concomitant injuries such as open dislocations, irreducible dislocations, and neurovascular compromise necessitate operative treatment. Operative treatment for the dislocated knee has been suggested to have superior outcomes compared to non-operative treatment [13]. However, non-operative management may be indicated in patients with minimal injury and sedentary lifestyle [14]. There exists great variation among the extent of ligaments damaged upon initial injury. For this reason, our review’s inclusion criteria necessitated a comparison of pre-operative to postoperative scoring. Based upon the weighted mean improvement of Lysholm scoring from 30.3 to 86.2 it appears that patients are able to obtain near normal restoration of functional outcomes [15].

A further topic of controversy exists whether to reconstruct or repair damaged tissues in the MLKI. In our review, reconstruction typically occurred for the ACL and PCL while repair occurred for medial collateral ligament (MCL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), posteromedial complex (PMC), posterolateral complex (PLC). One cohort Sun L, et al. [12] used repair only technique and this did not appear to have an inferior result in improvement of post-operative Lysholm score. Certain structures such as the posterolateral corner may be amenable to reconstruction vs repair [16].

The timing of surgical repair may be a factor in optimizing outcomes in the MLKI. Barring extensive soft-tissue loss or life/ limb-threatening injury, delay in surgery or two stage surgery may be appropriate. Two of the cohorts included in this review opted for two stage reconstruction [10,12]. Lai et al repaired MCL, PLC and meniscus during the first operation followed by a second operation 3-6 months later where the ACL and PCL were reconstructed arthroscopically [10]. The reason for delay in surgery was to restore normal level of knee range of motion. The two-staged cohort by Sun et al consisted of PMC or PLC repair during an initial surgery followed by a second stage of operation 8-10 weeks later during which ACL and PCL were reconstructed arthroscopically [12]. Interestingly, the cohort within Sun et. al s study consisting solely of extra-articular ligamentous repair did not have a statistically significant difference in Lysholm outcomes scores in comparison with the reconstructive groups. This finding suggests the importance of establishing extra-articular stability by means of LCL, MCL, PMC, PLC repair.

Treatment in the acute phase (within 2 weeks of injury) leads to improved functional outcomes compared to delayed surgery [17-20]. In our review, 3 studies acknowledged an operative intervention within the acute phase (6-8). Interestingly, Xu et al noted a time of 1.2 months to operation and was found to have the lowest post-operative Lysholm scores compared to the other cohorts [11]. It is unreasonable to find a universally suitable treatment algorithm that can encompasses all patients. Instead, management should occur according to surgeon-patient discussion and concomitant injury [21]. Additionally, rehabilitation protocol in the MLKI is another important factor that must be personalized to each patient and will allow for full recovery potential [22,23].

An important limitation of this study was the level of evidence of the included studies. All were case series consisting of retrospective reviews of an unmatched cohort of patients. Subsequently, it is difficult to give definitive quantification of improvements following knee dislocation injuries. Furthermore, while an original aim was to subdivide surgical methods and stages, insufficient data exists to provide a numerical comparison. However, based upon available literature, this manuscript is able to provide reasonable analysis of the improvements in functional outcome scores following MLKI reconstruction and/or repair (Table 1 &2), (Figure 1 & 2).

Table 1: Study design and patient demographics of included multi-ligament knee reconstruction studies. NR = not reported.

Table 2: Tissue pathology, surgical treatment methods and outcome scores of multi-ligament knee reconstruction studies. ACL = anterior cruciate ligament, PCL = posterior cruciate ligament, MCL = medial collateral ligament, LCL = lateral collateral ligament, PLC = posterior lateral corner, PMC = posterior medial complex.

Conclusions

A review of the current literature concludes that surgical ligamentous repair and/or reconstruction of the MLKI yields a significant improvement from pre-operative to post-operative Lysholm scores. This suggests that surgical intervention provides benefit to patients in this population. Other outcome scores have insufficient data to conduct a statistical analysis.

Acknowledgment

This research was not supported by any grant or financial contribution.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Rihn JA, Groff YJ, Harner CD, Cha PS (2004) The acutely dislocated knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 12(5): 334-346.

- Stuart MJ (2001) Evaluation and treatment principles of knee dislocations. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine 9(2): 91-95.

- Fanelli GC, Orcutt DR, Edson CJ (2005) The multiple-ligament injured knee: evaluation, treatment, and results. Arthroscopy 21(4): 471-486.

- Jones RE, Smith EC, Bone GE (1979) Vascular and orthopedic complications of knee dislocation. Surg Gynecol Obstet 149(4): 554-558.

- Arom GA, Yeranosian MG, Petrigliano FA, Terrell RD, McAllister DR (2014) The changing demographics of knee dislocation: a retrospective database review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472(9): 2609-2614.

- Qiu J, Lin R, Lin W, Huang X, Xiong G (2015) Reconstruction for knee dislocation with multiple ligaments injury at stage I. Zhongguo Gu Shang 28(12): 1095-1099.

- Chen P, Zhu Z, Wang S (2012) One-stage repair and reconstruction of knee anterior cruciate ligament, posterior cruciate ligament, and medial collateral ligament. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 26(6): 675-678.

- Jiang W, Yao J, Kong D (2014) Effectiveness of One-Stage Repair and Reconstruction of Traumatic Dislocation of Knee Joint Combined with Multiple Ligament Injuries. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 28(7): 810-813.

- Duan X, Yang Y, Xiao G (2008) Clinical effect of arthroscopically assisted repair and reconstruction for dislocation of the knee with multiple ligament injuries. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 22(6): 673-675.

- Lai Z, Liu Z, Yang J, Zhang Z, Chang Y (2016) [Clinical effect of staged repair and reconstruction of multiple ligament injuries in knee joints]. Zhongguo Gu Shang 29(5): 404-407.

- Xu H, Chen Y, Zhai L, Bi D (2016) Surgical treatment of multiple ligament injuries of knee joints. Zhongguo Gu Shang 29(5): 456-459.

- Sun L, Wu B, Tian M, Luo YZ (2016) Results of multiple ligament injured knees operated by three different strategies. Indian J Orthop 50(1): 43-48.

- Dedmond BT, Almekinders LC (2001) Operative versus nonoperative treatment of knee dislocations: a meta-analysis. Am J Knee Surg 14(1): 33-38.

- Kannus P, Järvinen M (1990) Nonoperative treatment of acute knee ligament injuries. A review with special reference to indications and methods. Sports Med 9(4): 244-260.

- Briggs KK, Steadman JR, Hay CJ, Hines SL (2009) Lysholm score and Tegner activity level in individuals with normal knees. Am J Sports Med 37(5): 898-901.

- Stannard JP, Brown SL, Farris RC, McGwin G, Volgas DA (2005) The posterolateral corner of the knee: repair versus reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 33(6): 881-888.

- Liow RYL, McNicholas MJ, Keating JF, Nutton RW (2003) Ligament repair and reconstruction in traumatic dislocation of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 85(6): 845-851.

- Harner CD, Waltrip RL, Bennett CH, Francis KA, Cole B, et al. (2004) Surgical management of knee dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86(2): 262-273.

- Tzurbakis M, Diamantopoulos A, Xenakis T, Georgoulis A (2006) Surgical treatment of multiple knee ligament injuries in 44 patients: 2-8 years follow-up results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 14(8): 739-749.

- Hohmann E, Glatt V, Tetsworth K (2017) Early or delayed reconstruction in multi-ligament knee injuries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee 24(5): 909-916.

- Levy BA, Fanelli GC, Whelan DB (2009) Controversies in the treatment of knee dislocations and multiligament reconstruction. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 17(4): 197-206.

- Edson CJ, Fanelli GC, Beck JD (2011) Rehabilitation after multiple-ligament reconstruction of the knee. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 19(2): 162-166.

- Medvecky MJ, Zazulak BT, Hewett TE (2007) A multidisciplinary approach to the evaluation, reconstruction and rehabilitation of the multi-ligament injured athlete. Sports Med 37(2): 169-187.

-

David S Constantinescu, Eric Curtis, James R Satalich, Alexander R Vap. Reconstruction and/or Repair of The Multi-Ligament Knee Injury: A Systematic Review. Glob J Ortho Res. 3(2): 2021. GJOR.MS.ID.000559.

-

Multiple ligament knee injury, Multiple knee ligament reconstruction, Multiple knee ligament repair, Knee ligament, Injured tissues, Demographics, Posteromedial complex

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.