Case Report

Case Report

Prevention Program to Prevent Chronic Pain, Substance Use Disorders, and Social Impact

Sarah Shueb1,2 and James Fricton2,3*

1Adjunct faculty, University of Minnesota, USA

2Pain Specialist, Minnesota Head and neck Pain Clinic, USA

3Professor Emeritus, University of Minnesota, pain Specialist, Minnesota Head and neck Pain Clinic, USA

Corresponding AuthorJames Fricton, Professor Emeritus, University of Minnesota, pain Specialist, Minnesota Head and neck Pain Clinic, USA

Received Date:March 11, 2024; Published Date: May 01, 2024

Abstract

Chronic pain conditions affect an estimated 100 million American adults, that’s more than heart disease, diabetes and cancer combined. An estimated $635 billion is spent annually on treating and managing chronic pain. Many people in chronic pain are not adequately treated with current therapies. Although opioids are the most effective analgesics, however, the use of opioids for the treatment of chronic non-cancer pain is controversial due to concerns about tolerance, abuse, and addiction. When acute pain becomes chronic, it is often associated with depression, disability, and intensive use of health care that can escalate to high-cost high-risk interventions such as opioid analgesics, multiple medications, and surgery. These treatments have the potential for poor long-term outcomes due to the lack of addressing patient-centered risk factors. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) stated that health professionals’ primary role for chronic pain should be guiding, coaching, and assisting patients with this dayto- day self-care.

However, this is rarely done as health professionals lack the time, training, tools, and reimbursement to guide patients in self-care. Research on tools and strategies to implement self-care training programs is greatly needed. We developed an innovative online patient-centered platform called Pain Prevention Program (PPP) to provide a reimbursable solution for health professionals to include self-care training in routine health care. PPP uses an evidence-based cognitive-behavioral online training program supported by a telehealth coach to help patients reduce risk factors that contribute to delayed recovery and implement daily protective self-care behaviors including healthy habits, exercise, mindfulness, and relaxation. PPP includes online risk self-assessments, micro-lessons, a self-monitoring dashboard and telehealth coaching to support long-term change in pain and opioid use. In this paper we evaluate the outcomes of the PPP in clinical settings on 25 patients with chronic pain.

Keywords:Chronic Pain; Health Care; Opioid Crisis; Pain Prevention; Health Coaching; Telehealth Coaching

Abbreviations:CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; CCM: Chronic Care. Model; CDC: Centers for Disease Control; ROI: Return on Investment; PEP:Patient Engagement Portal; PPP: Pain Prevention Program

Introduction

Chronic pain is the big elephant in the room of health care. It is the top reason to seek care, the #1 cause of disability and opioid addiction, and the primary driver of healthcare utilization, costing more than cancer, heart disease, and diabetes [1-9]. More than half of the persons seeking care for pain conditions at 1 month still have pain 5 years later despite treatment due to lack of training patients in reducing the many lifestyle risk factors that lead to delayed recovery and chronic pain due to lack of patient self-management training [10-12]. This delayed recovery is primarily due to the lack of addressing many patient-centered risk factors such as poor ergonomics, repetitive strain, inactivity, prolonged sitting, stress, sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, abuse, and many others that increase peripheral and central pain sensitization and lead to chronic pain and its consequences of disability, work loss, and addiction [13-19].

If usual care fails, clinicians and patients often escalate care to passive higher-risk interventions such as opioids, polypharmacy, surgery, or extensive medical and dental treatment instead of training patients to reduce the risk factors [5-9]. Yet, clinical trials have shown that the long-term outcomes of these passive interventions are no better and, in many cases, worse than patient-centered approaches that activate and empower patients with self-management strategies such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), therapeutic exercise, and mindfulness-based stress reduction to help patients lower risk factors for chronic pain and addiction by implementing protective actions [12-40]. However, health professionals cite the lack of reimbursement, adequate time, and skills as reasons why the critical task of self-management training rarely occurs in the health care system [1,2].

The Pain Prevention Program (PPP) was developed and tested with funding from the National Institutes of Health to support health professionals in implementing transformative care to prevent chronic pain substance use disorders, social impact, and the opioid crisis. PPP helps healthcare professionals add patient engagement in self-management training to be smoothly integrated with treatment to improve long-term outcomes of pain conditions and prevent chronic pain and addiction. This paper describes case series of using the Pain Prevention Program for transformative care using the Pain Prevention Program and its Patient Engagement Portal (PEP) to help prevent the chronic pain, substance use, and functional interference.

Preventing the Opioid Crisis: Chronic pain is also the primary reason for developing opioid addiction and the current opioid crisis. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the most recent data estimates that 142 Americans die every day from a drug overdose. Since 1999, the number of deaths from prescription opioids has more than quadrupled and are now about 100,000 deaths per year, a greater number than from motor vehicle accidents and gun homicides combined.2 From 2000-2021, there was alarming 800,000 deaths from opioid overdoses, with many under the age of 40 years.6-7 Since the opioids are often blamed for this crisis, the solution most providers are currently implementing involves withdrawal and denial of the use opioids for pain conditions. This does not address the specific pain condition that the patient has or if they have addiction behavior, which may also involve illicit drugs, gambling, sugar, social media or other addictions. Medication replacement strategies with less addicting opioids is another common strategy to help patients taper off the use of opioid but does not address the continued chronic pain that they may have. Interventions including physical therapy, chiropractic therapy, injections, implants and other passive pain treatments are often used by health professionals to help with pain but may be temporary if patient-centered risk factors continue. A patient-centered multi-modal approach is needed to prevent both chronic pain and addiction behaviors that includes both treatments as well as training of patients in self-management strategies to reduce risk factors and improve protective actions such as healthy habits, mindful pauses, and calming practice. Transformative care provides both patient self-management training with treatments to improve the pain with immediate treatment while addressing the risk factors that lead to chronic pain.

Pain Prevention Program (PPP): The PPP program engages

participants through 5 strategies including: 1) chronic pain risk

assessment, 2) chronic pain and addiction risk reduction training,

3) telehealth coaching, and 4) remote telehealth monitoring with a

patient-centered dashboard. PPP is accessible by any on-line device

and integration with preventive medicine counseling with the care

of their health professional, a family and friend support network,

addressing the whole person, engaging animated characters,

interactive content, simple but powerful action plans, outcomes

and engagement dashboard, reminders, written handouts

and more. The goal of PPP is to help participants to learn selfmanagement

strategies that will result in less pain, better function,

less medication, and less need for on-going healthcare to achieve

the Institute for Health Care Improvement’s triple aim of improving

the patient’s experience and engagement in care, enhancing the

health of the patient, and controlling the cost of health care [41-

44]. An analysis of the cost impact that the PPP patient-centered

pain program can have demonstrated that the total cost of care for

patients with pain conditions can be reduced by 50% or more with

estimated minimum 8:1 annual Return on Investment (ROI) with

long-term sustainability in future years [45-46]. Using these figures,

it is estimated that health plans can reduce the total cost of care by

billions of dollars annually by integrating patient-centered self-care

programs such as PPP for their members. PPP has completed a full

research and development cycle to allow broad implementation.

The PPP and core technologies include:

a) Pain and Risk Assessment: Digitally delivered validated

assessment tool that assesses patients’ pain, risk and protective

factors in all areas of a patient’s life, readiness to change, and

adherence to training. This innovative assessment is used

by health coaches and health providers to better understand

a patients’ personal characteristics, risks, and outcomes

associated with a specific chronic condition and develop

personalized care programs.

b) Digital Training Platform: The digital platform is licensed

by health professionals is similar to an electronic health record

systems, except focused patient engagement. It integrates

algorithms based on risk assessments to personalize selfmanagement

training of patients to reduce the cause of pain. It

also documents outcomes with remote tracking for the provider

and telehealth coaching. The platform also engages social

support, allows for health coach documentation, and billing

within a clinic setting to offer self-manage pain conditions. It

also creates a network of health care providers to document

aggregate outcomes and allow for predictive analytics to

improve long-term successful management.

c) Telehealth Coaching: Telehealth coaches are both trained

in advanced education programs and are nationally board

certified in health coaching [35-38]. Health coaches provide

support for pain self-management with telehealth visits to

provide support to patients in making the lifestyle changes

needed to recover from pain conditions in addition to medical

and rehabilitative interventions. Health coaching has been

shown to enhance outcomes. PPP also leverages a supportive

social network of family, friends, and health professionals to

enhance motivation, understanding, and compliance, thereby

improving long-term success [47-59].

d) Remote Monitoring Dashboard: A dashboard presents

data to health coaches, health professionals, patients, and

support team to better understand the personal characteristics

of patients and track their progress. The dashboard includes

results of baseline assessment of each patient’s personal

characteristics, pain characteristics, current self-care, risk

factors, protective actions, patient engagement, pain severity,

and life interference. In addition, follow-up assessments provide

detailed data on patient progress in both engagement in selfmanagement

as well as improvement in pain and interference.

Methods

To evaluate outcomes of the PPP in clinical settings, a case

series of 25 patients with chronic pain were evaluated in the clinical

setting. PPP was implemented in three phases that included shared

decision-making at each health care visit including:

1. Initial patient-centered focused clinical evaluation with

transformative care treatment planning,

2. PPP implementation with assessment and telehealth

coaching,

3. And Follow-up visits including preventive medicine

counseling.

Standard treatment was also implemented including preventive medicine counseling, office visits, physical therapy, and protective splint.

Results

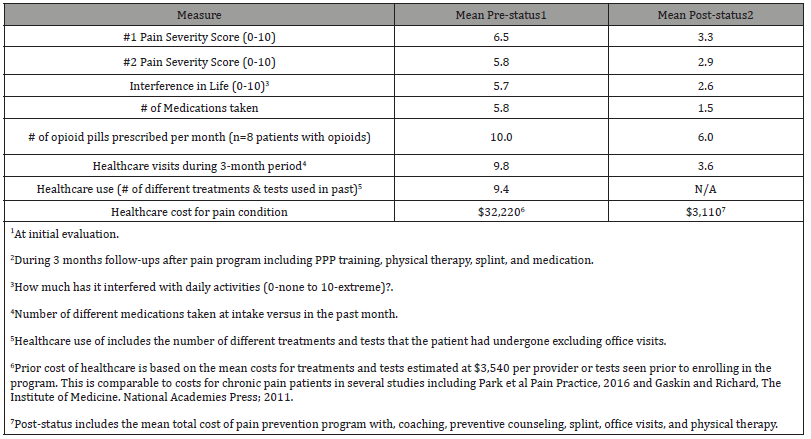

(Table 1) shows the pre- and post- data was collected on engagement in the PPP program and validated scales of pain severity, personal impact, life interference, and prior health care use. In addition, data was collected for the mean number of medications, number of opioid pills prescribed, healthcare visits, healthcare use, and healthcare costs. The PPP program was also reimbursed by health plans as preventive services to prevent chronic pain and addiction.

Table 1:Impacts of Pain Prevention Program from Electronic Health Records (n=25) with mean age 32.7 years, 70% female). Patients had a mean of 3.3 modules viewed and 5.7 Coach visits.

Discussion

This case series found that self-management strategies can be helpful in reversing pain cycles, chronic pain, and substance use disorders, and social impacts. Systematic reviews of studies evaluating each component of the PPP program including healthy habits, pauses, calming, coaching, and on-line training has demonstrated clear positive outcomes [60-83]. For example, reviews of social support and health coaching show that they can improve functional recovery from chronic pain [60-64]. Systematic reviews of randomized clinical trials of web-based cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise, and lifestyle changes show significant improvement with chronic pain [65-76]. Systematic reviews of mindfulness-based stress reduction demonstrate a significant Impact in reducing chronic pain [23-26], as did systematic reviews of meditation and relaxation training [77-84], By integrating these strategies within the PPP e-health training platform, it can better engage, empower, and educate patients in understanding the pain cycles set up from a combination of risk factors and then learning the skills of long-term self-management of them while implementing protective actions to relieve chronic pain [80-102].

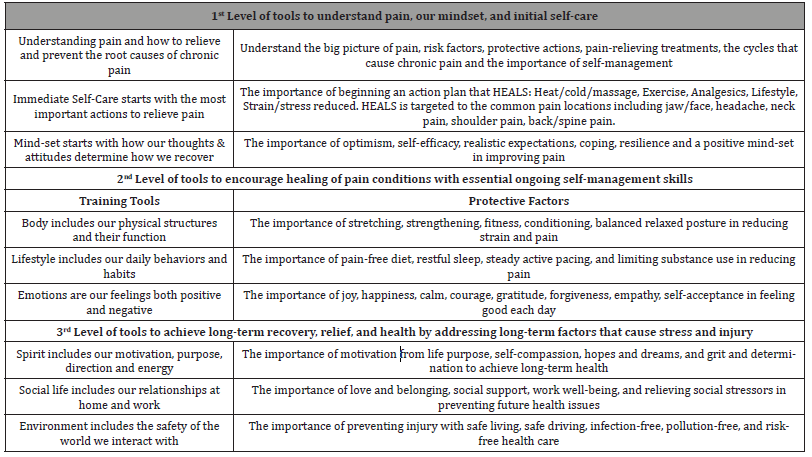

Chronic Care Model (CCM). The PPP program is also based on the Chronic Care Model by integrating patient-centered selfmanagement with evidence-based treatment [53-58] The CCM has documented evidence of its efficacy for many chronic conditions in more than 100 healthcare organizations [53-58]. The PPP program uses each of the 12 principles of implementing evidence-based self-management as part of routine patient care [53] including: 1) brief targeted assessment, 2) evidence-based information to guide shared decision-making, 3) use of a nonjudgmental approach, (4) collaborative priority and goal setting, 5) collaborative problem solving, (6) self-management support by diverse providers including health coaches, 7) self-management interventions delivered by diverse formats, 8) patient self-efficacy measured and trained, 9) active follow-up, reminders, and reinforcement, 10) guideline-based case management for selected patients, 11) linkages to social support and community programs, and 12) multifaceted interventions. These can be implemented in three phases for improved shared decision-making at each health care visit: 1) enhanced pre-visit assessment, 2) a focused clinical encounter, and 3) expanded post-visit options. These can be reimbursed by health plans and are part of the teaching curriculum for transformative care training program for health professionals and health coaches (Table 2).

Table 2:Self-Management Tools to help understand pain and how each of the 7 realms of our lives can help relieve and prevent chronic pain and addiction.

PPP Supports Change with Telehealth Coaching [103-105]. Health coaching is relationship-centered, client-driven process designed to facilitate and empower a client to achieve selfdetermined goals related to health and overall well-being. While client goals may be informed by or suggested by others, such as an individual’s physician or other health provider, the selection of the goal and exploration where one is in relationship to the goal is up to the client. Telehealth Coaching is an integral part of the Pain Prevention Program. Telehealth Coaches within PPP are nationally certified health professionals who are well-trained to review risk assessments and provide self-management training to patients with pain conditions to facilitate their knowledge and skills necessary for self-management. The process incorporates the needs, goals and life experiences of the patients and is guided by evidence-based interventions for the target condition. Systematic reviews of social support and health coaching show they improve functional recovery from chronic pain [35-43].

Individuals may be just beginning to consider a change, may

be exploring aspects of preparing for a change, or may be ready

to implement actual actions. Health coaching is provided in a safe

and consistent space to support positive change in health and wellbeing.

Clients can explore their thoughts, emotions, and actions, in a

way that allows them to recognize the power of their own choices to

impact their wellness. Health Coaching is a methodology that differs

from health education or counseling or therapy, though it can work

well in combination with those other practices. Health Coaches

assume that people have strong intrinsic resources and strengths,

can access the self-motivation needed to function autonomously

and competently, and are able to realize positive change within a

safe and confidential alliance, where they are inspired, respected,

and supported. By applying clearly defined knowledge and skills,

they support individuals or groups in mobilizing their internal

strengths and external resources to achieve sustainable changes

in beliefs or behaviors. Health Coaching has the potential to help

individuals, families, and groups achieve improved health and

wellbeing by:

a) Setting goals: While a person’s goals may be informed

by the condition, such as to reduce the pain, or suggested by

others, such as a health professional or the on-line training

such as to do exercise, the health coach will help with selection

of the goal and exploration where one is relationship to the goal

is up to the client.

b) Practice grounding and calming: The first step in coaching

is to help a person be grounded in the moment to practice

calming.

c) Facilitating Change: Individuals may be just beginning to

consider a change, may be exploring aspects of preparing for a

change, or may be ready to implement actual actions. In a safe,

consistent, non-judgmental, and supportive space, clients can

explore their thoughts, emotions, and actions, in a way that

allows them to recognize the power of their own choices to

impact their wellness.

d) Empowering people. Health coaches assume that people

have strong intrinsic resources and strengths and can access

the self-motivation and energy needed to accomplish their

goals.

e) Engaging responsibly. Health coaches assume that

people will function autonomously and competently and are

able to realize positive change within a safe and confidential

alliance with the health coach. The coach relationship is one of

inspiration, respect, and non-judgmental support.

f) Achieving goals. By applying clearly defined knowledge

and skills, the health coach can support individuals or groups

in mobilizing their internal strengths and external resources

to achieve sustainable changes in thoughts, emotions, and

behaviors to achieve their goal of improved health and

wellbeing.

Case Study

The experiences of Jessica, a 28 year-old patient, can help explain why the average cost per year for each pain patient is about $12,000 instead of about $3,000 for non-pain patients and how the PPP program can help reduce this social impact. Jessica has had many pain conditions including hip pain, back pain, hand wrist pain, neck and shoulder pain, migraine headaches and temporomandibular pain for many years. Recently, she was verbally abused at work because of her poor performance, which lead to post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, and more pain. In addition, her work position in a medical center call center forced her into poor posture with repetitive strain from talking, clenching her teeth, and looking up all day. The pain kept her up at night and her resultant fatigue, high caffeine use, and tensing caused more pain and headaches. When the pain flared, she went to the urgent care to help her control the pain. Her physician prescribed antianxiety, anti-depressants, and opioid pain medications for years which she often over-used with many daytime side effects.

Because of the persistent pain and anxiety, she requested a 3-month medical leave to recover from the pain and stress at work. She also was seen by a pain specialist, orthopedic surgeon, behavioral therapist, physical therapist, and occupational therapist. Surgery was going to be the next step if she did not recover. She had many pain cycles that were sustaining her pain from risk factors in each realm of her life. Then, she went through the 6-month pain prevention program supported by her health coach to understand the big picture of what lifestyle factors was causing her physical pain condition to persist. By becoming empowered and engaged in her own health, she was able to maintain her healthy habits (exercise, posture, diet, sleep), pauses (mindfulness), and calming practice (relaxation) each day. She reduced her healthcare and treatments because she became confident in self-managing her own pain and was able shift to protective actions that help her maintain positive emotions, thoughts, relationships, motivation, and behaviors. This helped her get back into the workforce with a job that she enjoyed and did not cause repetitive strain. She is also much happier with better relationships and a brighter future.

Patients have made many positive comments about the use

of PPP as part of routine care for pain conditions. Some of the

comments include:

“PPP was the most valuable part of my treatment plan and

taught me many self-management strategies that do regularly to

relieve and prevent my pain” –Kathy, age 38 years.

“PPP has provided me confidence that I can self-manage my

pain with some simple strategies and avoid the ongoing treatments

and medications for pain that I have used for years. Monica, age 24

year.

“PPP is incredibly helpful. I expect that in 10 years every doctor

in the country will be using PPP as part of their treatment for pain.”

–Zoe, age 62.

Conclusion

As noted, chronic pain is the big elephant in the room of health care. It is the top reason to seek care, the #1 cause of disability and addiction, and the primary driver of healthcare utilization, costing more than cancer, heart disease, and diabetes. More than half of the individuals seeking care for pain conditions at 1 month still have pain 5 years later despite treatment due to lack of training patients in reducing the many lifestyle risk factors that lead to delayed recovery and chronic pain due to lack of patient self-management training. [5-9] They cite the lack of reimbursement, adequate time, and skills as reasons why the critical task of self-management training rarely occurs in the health care system.1 Yet, there is ample evidence to demonstrate that patient-centered approaches such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), therapeutic exercise, and mindfulness-based stress reduction can activate and empower patients in reducing risk factors for chronic pain and implementing protective actions to improve pain long-term [17-40].

References

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education (2011) Relieving Pain in America. A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA.

- Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee (2016) National pain strategy: a comprehensive population health-level strategy for pain. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health Washington, DC, US.

- Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guidelines for Chronic Pain.

- Hooten WM, Timming R, Belgrade M, Gaul J, Goertz M, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Assessment and Management of Chronic Pain.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R (2016) CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain--United States. JAMA 315(15): 1624–1645.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services Strategy to Combat Opioid Abuse, Misuse, and Overdose. A Framework Based on the Five Point Strategy.

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya, C, Linda Porter, Charles Helmick, et al. (2018) Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67(36): 1001–1006.

- Darrell J Gaskin, Patrick R (2011) Appendix C. The Economic Costs of Pain in the United States. in the Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. National Academies Press, Washington DC, USA.

- Park PW, Dryer RD, Hegeman-Dingle R, Mardekian J, Zlateva G, et al. (2016) Cost Burden of Chronic Pain Patients in a Large Integrated Delivery System in the United States. Pain Practice 16(8): 1001-1011.

- Hestbaek L, Leboeuf-Yde C, Manniche C (2003) Low-back pain: what is the long-term course? A review of studies of general patient populations. Eur Spine J 12(2): 149-165.

- Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, Martin BI (2009) Over-treating chronic back pain: time to back off?. J Am Board Fam Med 22 (1): 62-68.

- Wilco, et al. (2011) Surgery versus conservative management of sciatica due to a lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 20: 513-522.

- Yunus MB (2008) Central sensitivity syndromes: a new paradigm and group nosology for fibromyalgia and overlapping conditions, and the related issue of disease versus illness. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 37(6): 339-352.

- McGreevy K Bottros MM, Raja SN (2011) Preventing Chronic Pain following Acute Pain: Risk Factors, Preventive Strategies, and their Efficacy. Eur J Pain Suppl 11: 365-372.

- Aggarwal VR, Macfarlane GJ, Farragher TM, McBeth J (2010) Risk factors for onset of chronic oro-facial pain-results of the North Cheshire oro-facial pain prospective population study. Pain 149(2): 354-359.

- Scher AI, Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Lipton RB (2003) Factors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based study. Pain 106(1-2): 81-89.

- Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Kristman V (2004) The annual incidence and course of neck pain in the general population: a population-based cohort study. Pain 112: 267–273.

- Lim PF, Smith S, Bhalang K, Slade GD, Maixner W (2010) Development of temporomandibular disorders is associated with greater bodily pain experience. Clin J Pain 26(2): 116-120.

- Scher AI, Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Lipton RB (2003) Factors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based study. Pain. 106(1-2): 81-89.

- Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams A (1999) Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain 80: 1–13.

- Harris P, Loveman E, Clegg A, Easton S, Berry N (2015) Systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapy for the management of headaches and migraines in adults. Br J Pain 9(4): 213-224.

- Gordon R, Bloxham S (2016) A Systematic Review of the Effects of Exercise and Physical Activity on Non-Specific Chronic Low Back Pain. Healthcare (Basel) 4(2): 22.

- Tang NK, Lereya ST, Boulton H, Miller MA, Wolke D, et al. (2015) Nonpharmacological Treatments of Insomnia for Long-Term Painful Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Patient-Reported Outcomes in Randomized Controlled Trials. Sleep 38(11): 1751-1764.

- Marley J, Tully MA, Porter-Armstrong A, Bunting B, O’Hanlon J, et al. (2014) A systematic review of interventions aimed at increasing physical activity in adults with chronic musculoskeletal pain-protocol. Syst Rev 3: 106.

- Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G (2013) A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. Clinical J of Pain 29: 450-460.

- Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Tomlinson G (2005) Systematic Review: Strategies for Using Exercise Therapy to Improve Outcomes in Chronic Low Back Pain. Ann Intern Med 142: 776-785.

- Chiesa A, Serretti A (2011) Mindfulness-based interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review of the evidence. J Altern Complement Med 17(1): 83-93.

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, et al. (2016) Mindfulness Meditation for Chronic Pain: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med 51(2): 199-213.

- Rosenzweig S, Greeson JM, Reibel DK, Green JS, Jasser SA, et al. (2010) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain conditions: variation in treatment outcomes and role of home meditation practice. J Psychosom Res 68(1): 29-36.

- Garmon B, Philbrick J, Becker D, Schorling J, Padrick M, et al. (2014) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for chronic pain: a systematic review. J of Pain Management 7: 23-36.

- Galante J, Galante I, Bekkers MJ, Gallacher J (2014) Effect of kindness-based meditation on health and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 82(6): 1101-1114.

- Kristine L Kwekkeboom, Elfa Gretarsdottir (2006) Systematic review of relaxation interventions for pain. J Nurs Scholarsh 38(3): 269-277.

- Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Sood A, Montori VM, Erwin PJ, et al. (2014) The efficacy of resilience training programs: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews 3(1): 20.

- Bailey KM, Carleton RN, Vlaeyen JWS, Asmundson GJG (2010) Treatments Addressing Pain-Related Fear and Anxiety in Patients with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain: A Preliminary Review. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy 39(1): 46-63.

- Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KMG, Bohlmeijer ET (2011) Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain 152(3): 533-542.

- Campbell P, Wynne-Jones G, Dunn KM (2010) The influence of informal social support on risk and prognosis in spinal pain: A systematic review. European journal of pain. 15(5): 444, e1-14.

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, Smeets RJEM, Ostelo RWJG, et al. (2015) Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 18: 350.

- Holden J, Davidson M, O'Halloran PD (2014) Health coaching for low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract 68(8): 950-962.

- Garg S, Garg D, Turin TC, Chowdhury MFU (2016) Web-Based Interventions for Chronic Back Pain: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 18(7).

- Buhrman M, Gordh T, Andersson G (2016) Internet interventions for chronic pain including headache: A systematic review. Internet Interventions 4: 17-34.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI) (2016) Triple Aim.

- Miles CL, Pincus T, Carnes D, Homer KE, Taylor SJC, et al. (2011) Can we identify how programmes aimed at promoting self-management in musculoskeletal pain work and who benefits? A systematic review of sub-group analysis within RCTs. Eur J Pain 15(8): 775. e1-e11.

- Clark, TS (2000) Interdisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: is it worth the money? Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). In this study, the 12-months reuction in costs as a result of pain rehabilitation in 17,600 patients was 56% 13(3): 240–243.

- Christopher D Sletten, Svetlana Kurklinsky, Vijit Chinburapa, Salim Ghazi (2015) Economic Analysis of a Comprehensive Pain Rehabilitation Program: A Collaboration Between Florida Blue and Mayo Clinic Florida. In this study, the 12-months reduction in costs as a result of pain rehabilitation in 53 patients was 56% 16(5): 898-904.

- Leonard L Berry, Ann M Mirabito, William B Baun (2010) What’s the Hard Return on Employee Wellness Programs? Harvard Business Review 88(12): 104-112.

- Ron Z Goetzel, Ronald J Ozminkowski (2008) The Health and Cost Benefits of Work Site Health-Promotion Programs. Annual Review of Public Health. 29: 303-323.

- James Fricton, Kathleen Anderson, Alfred Clavel, Regina Fricton, Kate Hathaway, et al. (2015) Preventing Chronic Pain: A Human Systems Approach—Results from a Massive Open Online Course. Global Adv Health Med 4(5): 23-32.

- Fricton JR (2015) The Need for Preventing Chronic Pain. Glob Adv Health Med 4(1): 6-7.

- Fricton JR, Gupta A, Weisberg MB, Clavel A (2015) Can we Prevent Chronic Pain? Practical Pain Management. 15(10): 1-9.

- Fricton J, Clavel A, Weisberg M (2016) Transformative Care for Chronic Pain. Pain Week Journal pp. 44-57.

- Fricton J, Whitebird R, Vazquez-Benitez G, Grossman E, Ziegenfuss J, et al. (2018) Transformative Self-Management for Chronic Pain Utilizing Online Training and Telehealth Coaching. Health Care Systems Research Conference Minneapolis.

- Grossman E, Vazquez-Benitez G, Whitebird R, Lawson K, Fricton J (2018) PPP-A Self-Management Program for Chronic Pain utilizing Online Education and Telehealth Coaching, Findings of the Pilot Study. Health Care Systems Research Conference Minneapolis.

- Sour E, Ziegenfuss J, Grossman E, Vazquez-Benitez G, Whitebird R, et al. (2018) Highly Motivated Population Provides Two Successful Recruitment Methods into the TMD Self-Care Study and PPP Program. Health Care Systems Research Conference

- Russell E Glasgow, Martha M Funnell, Amy E Bonomi, Connie Davis, Valerie Beckham, et al. (2002) Self-Management aspects of the improving chronic illness care breakthrough series: Implementation with diabetes and heart failure teams. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24(2): 80-87.

- Malcolm Battersby, Michael Von Korff, Judith Schaefer, Connie Davis, Evette Ludman, et al. (2010) Twelve Evidence-Based Principles for Implementing Self-Management Support in Primary Care. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety 36(12): 561-570.

- Russell E Glasgow, Connie L Davis, Martha M Funnell, Arne Beck (2003) Implementing Practical Interventions to Support Chronic Illness Self-Management. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety via Jt Comm. J Qual Patient Saf 29(11): 563-574.

- Alexander C Tsai, Sally C Morton, Carol M Mangione, Emmett B Keeler (2005) A Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Improve Care for Chronic Illnesses. Am J Manag Care 11(8): 478–488.

- Russell E Glasgow, Martha M Funnell, Amy E Bonomi, Connie Davis, Valerie Beckham, et al. (2002) Self-Management aspects of the improving chronic illness care breakthrough series: Implementation with diabetes and heart failure teams. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 24(2): 80-87.

- Perry M Gee, Deborah A Greenwood, Debora A Paterniti, Deborah Ward, Lisa M Soederberg Miller (2015) The eHealth Enhanced Chronic Care Model: A Theory Derivation Approach. J Med Internet Res 17(4): e86.

- Deede Gammon, Gro Karine Rosvold Berntsen, Absera Teshome Koricho, Karin Sygna, Cornelia Ruland (2015) The Chronic Care Model and Technological Research and Innovation: A Scoping Review at the Crossroads. J Med Internet Res 17(2): e25.

- Saee Hamine, Emily Gerth-Guyette, Dunia Faulx, Beverly B Green, Amy Sarah Ginsburg (2025) Impact of mHealth Chronic Disease Management on Treatment Adherence and Patient Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res 17(2): e52.

- Bennett HD, Coleman EA, Parry C, Bodenheimer T, Chen EH (2010) Health Coaching for Patients with Chronic Illness. Does your practice “give patients a fish” or “teach patients to fish”? Fam Pract Manag 17(5): 24-29.

- Foster G, Taylor SJC, Eldridge SE, Ramsay J, Griffiths CJ (2007) Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 17(4): CD005108.

- Jochen Gensichen, Michael von Korff, Monika Peitz, Christiane Muth, Martin Beyer, et al. (2009) Case management for depression by health care assistants in small primary care practices. Ann Intern Med 151(6): 369–378.

- Margarite J Vale, Michael V Jelinek, James D Best, Anthony M Dart, Leeanne E Grigg, et al. (2003) Coaching patients on achieving cardiovascular health (COACH): A multicenter randomized trial in patients with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 163: 2775–2783.

- Tiffany L Gary, Lee R Bone, Martha N Hill, David M Levine, Maura McGuire, et al. (2003) Randomized controlled trial of the effects of nurse case manager and community health worker interventions on risk factors for diabetes-related complications in urban African Americans. Prev Med 37(1): 23–32.

- J Holden, M Davidson, P D O'Halloran (2014) Health coaching for low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract 68(8): 950-62.

- Debora Duarte Macea, Krzysztof Gajos, Yasser Armynd Daglia Calil, Felipe Fregni (2010) The efficacy of Web-based cognitive behavioral interventions for chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain 11(10): 917–929.

- Bender JL, Radhakrishnan A, Diorio C, Englesakis M (2011) Can pain be managed through the Internet? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Pain 152: 1740–1750.

- Gratzer D, Khalid-Khan F (2015) Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy in the treatment of psychiatric illness. CMAJ 188(4): 263-272.

- Linda H Eaton, Ardith Z Doorenbos, Krisann L Schmitz, Kelly M Carpenter, Bonnie A McGregor (2011) Establishing treatment fidelity in a web-based behavioral intervention study. Nurs Res 60(6):430-435.

- Dean J Wantland, Carmen J Portillo, William L Holzemer, Rob Slaughter, Eva M McGhee (2004) The effectiveness of Web-based vs. non-Web-based interventions: a meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. J Med Internet Res 6(4): e40.

- Christine L Paul, Mariko L Carey, Rob W Sanson-Fisher, Louise E Houlcroft, Heidi E Turon (2013) The impact of web-based approaches on psychosocial health in chronic physical and mental health conditions. Health Educ Res 28(3): 450-471.

- Patrick W C Lau, Erica Y Lau, Del P Wong, Lynda Ransdell (2011) A systematic review of information and communication technology-based interventions for promoting physical activity behavior change in children and adolescents. J Med Internet Res 13(3): e48.

- Debora Duarte Macea, Krzysztof Gajos, Yasser Armynd Daglia Calil, Felipe Fregni (2010) The Efficacy of Web-Based Cognitive Behavioral Interventions for Chronic Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The Journal of Pain 11(10): 917-929.

- Marleen H van den Berg, Johannes W Schoones, Theodora P M Vliet Vlieland (2007) Internet-based physical activity interventions: a systematic review of the literature. J Med Internet Res 9(3): e26.

- L Kay Bartholomew, Patricia Dolan Mullen (2011) Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. Special Issue: Behavioral and Social Intervention Research Essentials 71(s1): 1752-7325.

- Jillian P Fry, Roni A Neff (2009) Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res 11(2): e16.

- Fricton J, Velly A, Ouyang W, Look J (2009) Does exercise therapy improve headache? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Current Pain & Headache Reports 13(6): 413-419.

- Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, Melissa L Anderson , Rene J Hawkes, et al. (2016) Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Usual Care on Back Pain and Functional Limitations in Adults With Chronic Low Back PainA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 315(12): 1240-1249.

- Elliot NG, Donna PF (1984) Factors associated with successful outcome from behavioral therapy for chronic temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 28(6): 441-448.

- Maixner W, Greenspan JD, Dubner R, Bair E, Mulkey F, et al. (2011) Potential autonomic risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. J Pain 12(11 Suppl): T75-T91.

- Mansour M (2002) Systems theory and human science. Annual Reviews in Control 26(1): 1-13.

- Bailey K (2006) Living systems theory and social entropy theory. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 23(3): 291-300.

- Miller JG (1978) Living systems. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-87081-363-3.

- Seppänen J (1998) Systems ideology in human and social sciences. In G. Altmann & W.A. Koch (Eds.), Systems: New paradigms for the human sciences. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter pp. 180–302.

- Rolland JS (1987) Chronic Illness and the Life Cycle: A Conceptual Framework. Fam Proc. 26: 203-221.

- Dym B (1987) The Cybernetics of Physical Illness. Family Process 26(1): 35–48.

- Turner JA, Holtzman S, Mancl L (2007) Mediators, moderators, and predictors of therapeutic change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain 127(3): 276-286.

- Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM (1994) Correlates of improvement in multidisciplinary treatment of chronic pain. J Consult Clin Psychol 62(1): 172-179.

- Jensen MP, Turner JA, Romano JM (1991) Self-efficacy and outcome expectancies: relationship to chronic pain coping strategies and adjustment. Pain 44(3): 263-269.

- Turner JA, Whitney C, Dworkin SF, Massoth D, Wilson L (1995) Do changes in patient beliefs and coping strategies predict temporomandibular disorder treatment outcomes? Clin J Pain 11(3): 177-188.

- Jensen MP, Nielson WR, Turner JA, Romano JM, Hill ML (2004) Changes in readiness to self-manage pain are associated with improvement in multidisciplinary pain treatment and pain coping. Pain 111(1-2): 84-95.

- Fricton JR, Nelson A, Monsein M (1987) IMPATH: microcomputer assessment of behavioral and psychosocial factors in craniomandibular disorders. Cranio 5(4): 372-381.

- Bigos SJ, Battie MC (1992) Risk factors for industrial back problems. Sem Spine Surg 4: 2-11.

- Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, Field AP (2002) A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine 27(5): E109-E120.

- Turk DC, Okifuji A (2002) Psychological factors in chronic pain: evolution and revolution. J Consult Clin Psychol 70(3): 678-690.

- Turner JA, Holtzman S, Mancl L (2007) Mediators, moderators, and predictors of therapeutic change in cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain 127(3): 276-286.

- Ohrbach R, Fillingim RB, Mulkey F, William Maixner, Gary Slade, et al. (2011) Clinical findings and pain symptoms as potential risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case-control study. J Pain 12(11 Suppl): T27-T45.

- John MT, Miglioretti DL, LeResche L, Von Korff M, Critchlow CW (2003) Widespread pain as a risk factor for dysfunctional temporomandibular disorder pain. Pain 102(3): 257-263.

- Litt MD, Shafer DM, Ibanez CR, Kreutzer DL, Tawfik-Yonkers Z (2009) Momentary pain and coping in temporomandibular disorder pain exploring mechanisms of cognitive behavioral treatment for chronic pain. Pain 145(1-2): 160-168.

- Litt MD, Shafer D, Napolitano C (2004) Momentary mood and coping processes in MS pain. Health Psychol 23(4): 354-362.

- Rammelsberg P, LeResche L, Dworkin S, Mancl L (2003) Longitudinal outcome of temporomandibular disorders: a 5-year epidemiologic study of muscle disorders defined by research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain 17(1): 9-20.

- Wright AR, Gatchel RJ, Wildenstein L, Riggs R, Buschang P, et al. (2004) Biopsychosocial differences between high-risk and low-risk patients with acute TMD-related pain. J Am Dent Assoc 135(4): 474-483.

- Wylie KR, Jackson C, Crawford PM (1997) Does psychological testing help to predict the response to acupuncture or massage/relaxation therapy in patients presenting to a general neurology clinic with headache? Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 17(2): 130-139.

-

Sarah Shueb and James Fricton*. Prevention Program to Prevent Chronic Pain, Substance Use Disorders, and Social Impact. Glob J Ortho Res. 4(5): 2024. GJOR.MS.ID.000597.

-

Osteogenesis imperfecta, non-telescoping rods, Fracture risk reduction, Recurrent fractures, Osteogenesis Imperfecta, Elastic Stable Intramedullary Nail

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.