Research Article

Research Article

Finding an Association Between Congenital Talipes Equinovarus (CTEV) and Developmental Dysplasia of Hip (DDH): Role of Early Ultrasonography

Khalid Hasan1*, Shamsi Abdul Hameed2, Aiman Mudawi3 , Shibly Abdul Basith4 and Mohamad Alaa Kawas5

1Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, USA

2Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar

3Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar

4Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar

5Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar

Khalid Hasan, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, USA.

Received Date: April 16, 2021; Published Date: May 07, 2021

Abstract

Introduction: Congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV) and developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) are common congenital anomalies. An association between these two conditions has been proposed, but no consensus has been reached. Purpose: The purpose of this study was to determine the incidence of sonographic hip dysplasia in infants with idiopathic clubfoot.

Methods: All neonates with a confirmed diagnosis of CTEV who were referred to our paediatric orthopaedic service for two years were clinically examined and screened with ultrasound for DDH using the Graf method.

Result: A total of 50 babies with CTEV were identified, 47 patients had physiologic hip dysplasia and 3 were found to have dislocated hips. The incidence of DDH in babies with CTEV was found to be higher than the normal population in our region.

Conclusion: Our study indicates higher risk for DDH in presence of CTEV and CTEV patients should be considered particularly for selective hip screening in our population.

Abbreviations: Developmental dysplasia of the hip; Congenital talipes equinovarus; Clubfoot; CTEV; DDH

Introduction

Clubfoot or congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV) and developmental dysplasia of hip (DDH) are conditions commonly encountered by orthopedic surgeons in their clinical settings. Both the conditions have unknown etiology. Genetic and environmental etiologies have been suggested for both, but with different pathways. Diagnosis of CTEV is simple and evident with clinical examination. DDH, on the other hand requires high clinical expertise for diagnosis and even the negative clinical signs do not rule out the condition completely. Ultrasound is recognized method to detect hip dysplasia. Routine clinical screening tests are sometimes conducted in babies with higher risk for DDH but lacks sensitivity. The renowned risk factors include positive family history, following breech delivery or with torticollis, and oligohydrominios. The early identification of children with DDH is valuable as it allows for less invasive treatment than if DDH is identified late [1]. However, the benefit of screening all children with ultrasonography is still controversial in literature.

Controversy persists in the literature as to a potential association between idiopathic structural congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV) foot deformity of the newborn and developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). Several studies have shown increased incidence of DDH in children with CTEV [2,3], whereas other studies have challenged that view suggesting that routine screening for DDH in cases of idiopathic CTEV is no longer advocated [4-6]. Hence, there remains a debate about the true association between CTEV and DDH.

We encounter patients from diverse ethnicity at Hamad General Hospital. We have followed all these patients that were referred to orthopedic service with an obvious clubfoot deformity with ultrasound screening of hips for 2 years. This observational cohort study was performed to assess if selective radiographic screening of hips in the clubfoot population is beneficial or not.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar. All cases of neonatal CTEV that were referred to the pediatric orthopedic service for evaluation in our hospital underwent routine clinical and ultrasound screening of the hips [7].

CTEV was diagnosed clinically based on the classical appearance of a fixed deformity combining equinus at the ankle, varus at the heel, supination at the mid-foot and adductus at the forefoot. Although CTEV was graded according to Pirani classification, it was not used for further in the study.

All basic details about the child were recorded. These included the patient biographic details, family history, prematurity, method and mode of delivery, history of multiple pregnancies, whether there was any complication during the delivery, and if the child has any other anomalies than the clubfoot. Children with CTEV have their hips examined clinically, all neonates’ hips were clinically examined for instability at the initial visit using the Barlow and Ortolani tests and screened with ultrasound for DDH. Static sonography was performed at the initial visit and followed at 6 weeks. Those with normal hips were not followed further. All ultrasounds were performed by the senior orthopedic consultant. The degree of dysplasia was classified according to Graf. Hips with Graf angle > 60° were classified as normal (type I), from 43° - 60° as type II (‘A’ if under three months of age, ‘B’ if aged over three months), < 43° and stable as type III and a dislocated hip as type IV. All type IIA (physiologic) underwent repeat ultrasound after three months to see if the abnormality persisted. Treatment was warranted for all babies with Graf type III or higher. Type IIB hips were regularly followed up and none required treatment.

Babies were followed up for a minimum of 2 years. As in other studies seeking to clarify an association between DDH and CTEV, we excluded all neonates with postural foot deformities, genetic syndromes or neuromuscular disorder, even though children with CTEV and DDH may have an underlying as yet undiagnosed syndrome.

Result

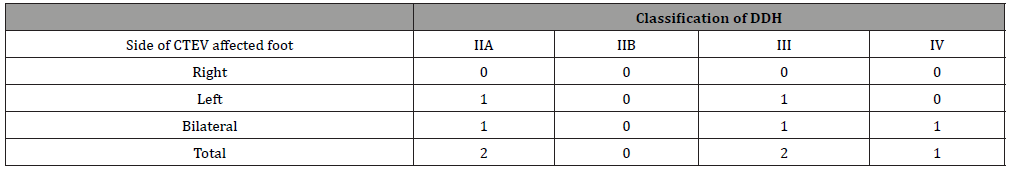

50 cases of congenital talipes equinovarus were referred to the orthopedic service during the study period and thus screened for hip dysplasia. There were 13 girls (26%) and 37 boys (74%). There were 18 cases (36%) of bilateral CTEV, 17 (34%) were left sided and 15 (30%) right sided.

Of the total 50 patients, 22 (44%) belonged to the local community (Qatari) whereas the rest were from varied backgrounds. 37 babies (74%) had spontaneous vaginal delivery (SVD). Of these, none was a breech presentation. 13 babies (26%) had caesarian section as method of delivery. 3 out of these 13 (23%) had breech presentation although none of these had a dysplastic hip. 2 babies were born prematurely at 32 and 33 weeks. None of the families had history of DDH previously, although 2 babies had their elder siblings that suffered from clubfoot.

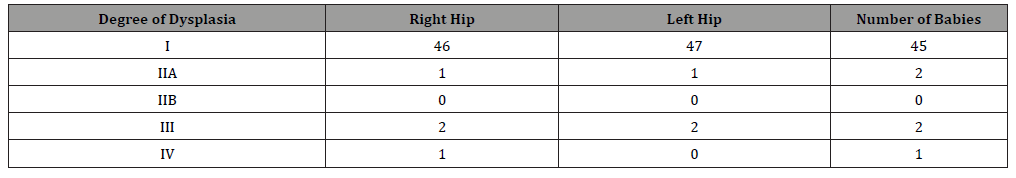

1 female child had dislocated hip on the right side (Graf type IV). She underwent management for CTEV and DDH and was followed for 3 years before she travelled abroad for further treatment. 2 male babies had bilateral dysplastic hip (Graf type III) while 2 male babies had a unilateral DDH (Graf type IIA) – (1 had a left sided clubfoot and a left sided DDH; the other had bilateral clubfoot but DDH on the right side only). These last two cases were followed and had their hip ultrasound done after 3 months and instigated treatment. All babies with Graf III or less were successfully treated with Pavlik harness without complications.

According to the findings 5 babies out of 50 with no other risk factors for DDH with CTEV had dysplastic hip diagnosed upon ultrasound screening. That is every 10th child of 100 births (10%) with congenital talipoequinovarus suffers from developmental dysplasia of hip.

Discussion

There is controversy in the literature regarding the association between CTEV and DDH and there is still debate about the true association between both conditions. Studies to date have shown a variation in the incidence of DDH in children with CTEV, but no consensus has been reached. RW Paton et al in a 21-year prospective observational study included 139 children with 199 cases of fixed idiopathic CTEV feet. Sonographically, there were only 18 hips with Graf Type II hips, 1 Graf Type III hip and 0 Graf Type IV hip [8]. Westberry et al looked at 349 babies with idiopathic CTEV. 127 had screening hip radiographs identifying 1 with hip dysplasia. 1 in 127 (0.7%) [9]. Recently, T Ibrahim et al in a systematic review and meta-analysis found that the prevalence of DDH in idiopathic clubfoot is similar to the normal population, based on that they did not recommend routine screening for DDH in children with idiopathic clubfoot [10].

On the other hand, the results from some other studies have suggested an association between clubfoot and DDH. BT Carney identified eight children (16%) with radiographic signs of hip dysplasia among fifty-one children with clubfoot [11]. D Zhao et al in an observational cohort study over a three-year period revealed that the idiopathic CTEV group had a greater incidence of DDH in comparison with the general population, 2.7 % of babies (five of 184) with idiopathic CTEV had DDH [12]. DC Perry et.al in an observational cohort study identified seven babies with hip dysplasia among 119 babies with CTEV, which means 1 in 17 babies with CTEV will have underlying hip dysplasia, supporting selective ultrasound screening of hips in infants with CTEV [13].

Ultrasound of the hip has a high sensitivity for the diagnosis of DDH compared with pelvic radiographs and clinical examination and has become the most effective modality for early detection of DDH. It is widely accepted that DDH identified at an early stage in infancy requires less invasive treatment than when presenting later [1]. Although, there is a controversy if early ultrasonography should be performed for the diagnosis of DDH in all babies, most studies recommend selective screening in high-risk population, including those with a positive family history, following breech delivery or with torticollis, oligohydramnios and deformities of the foot [9]. Several authors have considered children with idiopathic clubfoot as a defined subgroup of the population with an increased risk of DDH and recommend selective ultrasound hip screening [13].

According to unpublished data, incidence of DDH in our population is 8/1000 live births, in our study 3 out of 50 babies with CTEV have DDH (Hips with Graf type IIa were considered as physiologic immature and were not included). In other words, incidence of DDH in babies with CTEV is 6/100 live births. This figure suggests that our CTEV group has 7.5 times greater incidence of DDH than the normal population.

We have to acknowledge that this study has certain limitations. Small sample size which is due to the rare nature of these two conditions. Our study did not include a control group as ethical restriction prevented direct comparison to a control group (Table 1&2).

Table 1: Degree of dysplasia classified according to side of CTEV.

Table 2: Degree of dysplasia using the Graf classification.

Conclusion

Based on our study results, a higher incidence of DDH exists in the population of our patients with idiopathic CTEV and it appears that CTEV remains an important group for selective ultrasound hip screening. However, studies of good quality with a larger sample size to assess the association between the CTEV and DDH would be most appropriate next step.

Acknowledgement

This research was conducted after the approval from Medical Research Center (MRC) at HMC. We acknowledge the support from MRC throughout the study. None of the authors of the study have any other financial benefits associated with the study.

References

- Sampath JS, Deakin S, Paton RW (2003) Splintage in developmental dysplasia of the hip: how low can we go? J Pediatr Orthop 23(3): 352-355.

- Canavese F, Vargas-Barreto B, Kaelin A, De Coulon G (2011) Onset of developmental dysplasia of the hip during clubfoot treatment: report of two cases and review of patients with both deformities followed at a single institution. J Pediatr Orthop B 20: 152-156.

- Ziegler J, Thielemann F, Mayer-Athenstaedt C, Gunther KP (2008) The natural history of developmental dysplasia of the hip: A metaanalysis of the published literature. Orthopade 37(6): 515-516.

- Wynne-Davies R, A Littlejohn, J Gormley (1982) Aetiology and interrelationship of some common skeletal deformities. J Med Gen 19(5): 321-328.

- Westberry DE, Davids JR, Pugh LI (2003) Clubfoot and developmental dysplasia of the hip: value of screening hip radiographs in children with clubfoot. J Paediatr Orthop 23(4): 503-507.

- Paton RW, Choudry Q (2009) Neonatal foot deformities and their relationship to developmental dysplasia of the hip: a ten-year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg 91(5): 655-658.

- Graf R (1984) Fundamentals of sonographic diagnosis of infant hip dysplasia. J Pediatr Orthop 4(6): 735–740.

- Paton RW, Choudry QA, Jugdey R, Hughes (2014) Is congenital talipes equinovarus a risk factor for pathological dysplasia of the hip? A 21 years prospective, longitudinal observational study. JBJS (B) 96(11): 1533-1535.

- DE Westbay, Jon R Davids, Linda I Pugh (2003) Clubfoot and developmental dysplasia of hip: value of screening hip radiographs in children with clubfoot. J Ped Orthop 23(4): 503-507.

- T Ibrahim, M Riaz, A Hegazy (2015) The prevalence of developmental dysplasia of the hip in idiopathic clubfoot. A systemic review and met analysis. Int Ortho 39(7): 1371-1378.

- BT Carney, EA Vanek (2006) Incidence of hip dysplasia in clubfoot. J Surg Orthop Adv 12(2): 71-73.

- D Zhou, Weiwei Rao, Li Zhao, Jianlin Liu, Yaqing Chen, et al. (2013) Is it worthwhile to screen the hips in infants born with clubfeet? Int Orthop 37(12): 2415-2420.

- Perry DC, S M Tawfiq, A Roche, R Shariff, N K Garg, et al. (2010) The association between clubfoot and developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 92(11): 1586-1588.

-

Khalid Hasan, Shamsi Abdul Hameed, Aiman Mudawi, Shibly Abdul Basith, Mohamad Alaa Kawas. Finding an Association Between Congenital Talipes Equinovarus (CTEV) and Developmental Dysplasia of Hip (DDH): Role of Early Ultrasonography. Glob J Ortho Res. 3(2): 2021. GJOR.MS.ID.000560.

-

Developmental dysplasia of the hip, Congenital talipes equinovarus, Clubfoot, CTEV, DDH, Torticollis, Oligohydrominios, Controversial, Radiographic screening

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.