Research Article

Research Article

Clinical Presentation of Lumbosacral Spinal Canal Stenosis Among Sudanese Patients

Yasir A Mohamed Elhassan1*, Anas O Ahmed2, Qurashi M Ali3 and Siddig Omer M Handady4

1Department of Anatomy, University of Kordofan, Sudan

2Department of Radiology, University of Gezira, Sudan

3Department of Radiology, National University, Sudan

4Department of Obstetrical & Gynecology, Ibrahim Malik hospital, Sudan

Yasir Ahmed Mohammed Elhassan, Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine, university of Kordofan, Elobied, Sudan.

Received Date: December 26, 2018; Published Date: January 17, 2019

Abstract

Background: Spinal canal Stenosis is a disabling disease and a major health problem facing most of the population all over the world. Patients suffering from lumbar spinal stenosis develop pain, paresthesia’s, numbness, and weakness in the back and legs due to entrapment of the lumbosacral nerve roots in the constricted neural canal and foramina.

Objective: To determine clinical presentation of lower spinal canal stenosis among Sudanese patients.

Methods: It was retrospective -hospital based study comprises 101 patients (58 male and 42 female) of post-operative patients diagnosed as severe lumbosacral spinal canal stenosis and undergone de-compressive surgery at neurosurgery department of Alshaab Teaching Hospital and Ribat Teaching Hospital. Interviews using a tested questionnaire were used for data collection. Patients’ files were also studies to determine the type of operation done; the etiology of the disease, and MRI of the patients were reviewed. Examination of the weight and height were also done.

Results: Hundred and one (101) patients were selected, the age distribution ranged from 15 to 80 years with a mean (standard deviation) age of 57.0±2.2 years and the most affected patients were more than 50 years 41 (40.6%). It was observed that 59 (58.4%) participants were male and 42 (41.6%) were female. Lower limb numbness and/or tingling were the most common symptoms, occurring in 93 (92.1%) of the patients, followed by lower back pain in 92(91.1%), weakness in 70(69.3%) and sphincteric loss observed in 20 (19.8%). Symptoms were bilateral in 58(57.4%), asymmetrical in 95 (94.1%) and in 65 (64.4%) of patients involved the entire leg.

Conclusion: The present study highlighted the clinical presentation of spinal canal stenosis and showed that lower limb numbness and/or tingling were the most common symptom, followed by pain and weakness. Male patients were mainly affected and the age most affected by the spinal canal stenosis was more than 50 years.

Keywords: Clinical presentation, lumbosacral stenosis, Sudanese patients.

Clinical Image

The causes of lumbar spinal stenosis can be congenital or acquired [1]. Spondylosis, or degenerative arthritis affecting the spine, is the most common cause of lumbar spinal stenosis and typically affects individuals over the age of 60 years [2]. Progressive disc degeneration due to aging, trauma or other factors can lead to disc protrusion and/or loss of disc height with attendant loading of the posterior elements of the spine, including the facet joints. Facet joint arthropathy and osteophyte formation follow, along with hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum. All of these processes (facet osteophytes, ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, and disc bulging) can encroach on the central canal and the neural foramina. Spondylolisthesis, in which one vertebral body translates anteriorly or posteriorly with respect to an adjacent vertebral body can also occur, exacerbating the spinal canal narrowing. The L4-5 level is most commonly involved, followed by L5-S1 and L3-4.

The clinical features of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) were characterized in many studies and the hallmark of LSS was mainly neurogenic (or pseudo) claudication [3-7]. This is the tendency for symptoms, usually pain, to be exacerbated with walking, standing, and/or maintaining certain postures. Most reported relief with lying, sitting, or flexion at the waist (squatting, leaning forward) [5]. Claudication ranges according to these different studies are from 75% of up to 92% of the cases. In another study, a report of a lower sensitivity (60%) of neurogenic claudication for the diagnosis of LSS was available, however with an unclear standard for the diagnosis [8]. The aim of this study is to determine the clinical pattern of lower spinal canal stenosis among Sudanese patients.

Methods

It was retrospective -hospital based study of patients who were post-operative and diagnosed as having severe lumbosacral spinal canal stenosis and underwent de-compressive surgery at neurosurgery department of Alshaab Teaching Hospital and Ribat Teaching Hospital; the main two centers out of three which provide neurosurgery services in the country. Data was collected from 101 patients’ files (58 male and 43 females) after taking permission from the directors of the two hospitals, including demographic data, natural history of the disease, such as the type of operation done, the cause(s) of spinal stenosis which were diagnosed by consultant radiologist and confirmed by the neurosurgeon, in addition to MRI reports written by consultant radiologist and examination of the weight and height. All individuals in this study exhibited intermittent claudication, often accompanied by other symptoms such as radioculopathy and/or LBP.

Exclusion criteria: Individuals who suffered from developmental stenosis and fractures were excluded from the study.

Ethical clearance: Ethical approval was obtained from the Technical Ethical Committee (TEC), Faculty of Medicine, University of Gezira, Wad Median, Sudan.

Statistical analysis: The mean and standard deviation minimum, maximum and frequency values were calculated. Significant difference was set at P < 0.05. Analysis was conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) for windows, version 20.

Results

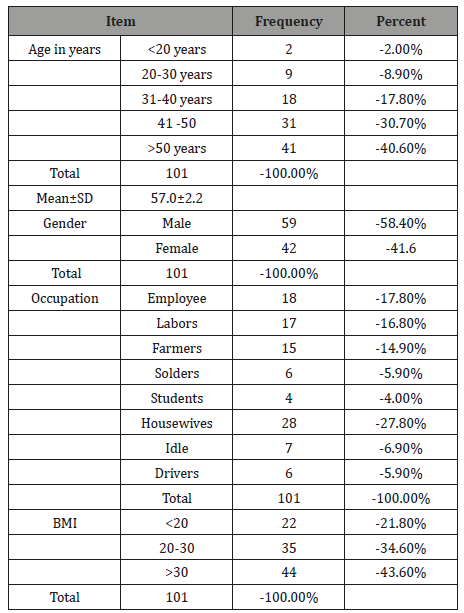

Table 1 shows demographic characteristic of the patients

Hundred and one (101) patients were selected, the age distribution ranged from 15 to 80 years with a mean (standard deviation) of age 57.0±2.2 years and the most affected patients were more than 50 years 41 (40.6%). It was observed that 59 (58.4%) participants were male and 42 (41.6%) were female. Their jobs were mainly employee 18 (17.8%), laborers 17 (16.8%), farmers 15 (14.9%) and house wives 28 (27.8%). The average height of patients was between 170-180, while their average weight was between 60-70kilograms and the Mean ± SD of BMI was 28.9±0.7

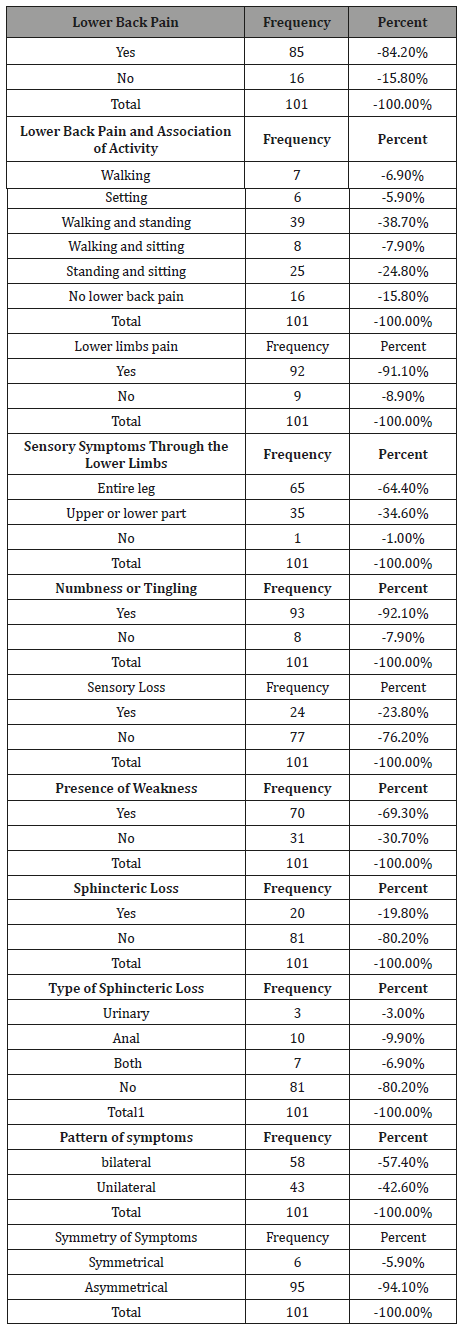

Table 2 shows clinical presentation of the patients

About eighty five percent of the patients (84.2%) had low back pain, which exacerbated with activity especially walking and standing (38.7%), walking, standing and sitting in (32.7%).

Sensory symptoms that affect the lower limbs

Lower limbs pain occurred in 92 (91.1%) of patients, while 93 (92.1%) of patients had numbness and tingling sensation, only 24 patients appreciated complete sensory loss at once during their illness (23.8%), sixty five patients (64.4%) had pain that involves the entire leg, while (34.7%) had pain affecting the upper and lower parts of the leg.

Motor Symptoms that Affect the Lower Limbs

Seventy patients had weakness in one or both lower limbs (69.3%) and thirty one of the patients (30.7%) had no lower limbs weakness.

Pattern of symptoms among the lower limbs

The symptoms were bilateral in most of the patients (57.4%), but often asymmetrical (94.1%).

Sphincteric Disturbance (Loss)

Most of the patients had no sphincteric loss (80.2%), out of the (19.2%) sphincter loss, 3 (3.0%) of them lost their urinary sphincters, 10 (9.9%) lost their anal sphincters, while 7 (6.9%) lost both the anal and urinary sphincters (Tables 1 & 2).

Table 1: Demographic Characteristic of Patient with Lumbosacral Spinal Canal Stenosis.

Table 2: Clinical Presentation of Patient with Lumbosacral Spinal Canal Stenosis.

Discussion

The present study revealed that, age distribution ranged from 15 to 80 years with a mean (standard deviation) of age 57.0±2.2 years and the most affected patients (40.6%) were elderly people (above 50 years old) which are consistent with the international pattern [9,2]. It was striking that the disease also affects young patients between 10 to 20 years of age, which it was also described by Boos and his colleagues [10,11] they found that discs degeneration occurs far earlier than other musculoskeletal tissues; the first unequivocal findings of degeneration in the lumbar discs were seen in the age group 11–16 years, about 20% of people in their teens have discs with mild signs of degeneration.

The results of this study showed that, male were more affected by the disease than female which is consistent to study done by [11]. Life style may have influence on the disease since most patients (nearly 50%) were laborers, officers or farmers. These occupations enhance the association between the job and the incidence of disc prolapsed.

In the current study about eighty five patients (84.2%) had low back pain, which exacerbated with activity especially walking and standing (36.6%), walking, standing and sitting in (27.7%). Many studies reported that, back pain as the striking symptom in case of LSS, together with lower extremity pain or other neurological symptoms [8,12-15]. McCombe PF, et al. [16] typically reported pain in the buttocks with or without radiation to the thighs and calves and numbness and weakness in the lower extremities provoked by walking or prolonged standing. Claudication ranges from (75% up to 92%) according to [8]. As shown in the literature the erect, extended position narrows the lumbar canal by reducing the interlaminar space, causing overlap of laminar edges of adjoining vertebral bodies, relaxing and inward buckling of the ligamentum flavum, and rostral-anterior migration of the superior facets [1,17]. This may explain the onset or persistence of symptoms with prolonged standing. Watanable & Porter also explained it by “It is also possible that increased metabolic demands on spinal nerve roots during walking may exceed the available microvascular blood flow, especially when intrathecal pressures are elevated” [18,19]. This explains why 97% of this study subjects back pain was associated with activity (walking, standing or sitting).

The clinical features of lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) were characterized in many studies and the hallmark of LSS was mainly neurogenic (or pseudo) claudication [3,4,6,7]. Some studies reported relief of the symptoms specially pain with lying, sitting, or flexion at the waist (squatting, leaning forward) [5]. Our results demonstrated that, lower limb numbness and/or tingling were the most common symptoms, occurring in (92.1%) of patients. This was followed by lower limb pain in (91.1%), and weakness in (69.3%). Complete sensory loss occurred during the disease period in about 23.8% of the patients. In contrast to the current study, other study revealed that lower limbs pain occurred in (93%), numbness and/ or tingling in (63%) and weakness in only (43%) [3]. This reflects the high pain tolerance of our patients that may be due to deficient and poor neurological medical coverage in the country. Symptoms were bilateral in 57.4% but asymmetrical in about (94.1%). These symptoms usually involve (64.4%) of the entire leg rather than just the upper or lower leg. This can be explained by the fact that the disc compresses centrally as well as bilaterally on both nerve root exits, but with more pressure on one side. It is almost comparable to what is mentioned by [8,15,20]. “The symptoms bilaterally in (68%), asymmetrical in (78%) and usually involved the entire leg in (15%)”. There was no association between the degree of spinal canal stenosis and the severity of symptoms was not shown among the patients. This finding is in accordance to what is mentioned by Boden, there is no substantive relationship between the severity of radiologic findings and the severity of clinical symptoms or prognosis, [9,21].

Conclusion

The present study highlighted the clinical presentation of spinal canal stenosis and showed that lower limb numbness and/ or tingling were the most common symptom, followed by pain and weakness. Symptoms were bilateral, asymmetrical, and usually involved the entire leg rather than just the upper or lower leg. Male patients were mainly affected and the age most affected by the spinal canal stenosis was more than 50 years. The study definitely helps to know the pattern of spinal canal stenosis and to plan future strategies for early diagnosis & timely management.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflict of Interest.

References

- Binder DK, Schmidt MH, Weinstein PR (2002) Lumbar spinal stenosis. Semin Neurol 22(2): 157-166.

- Atlas SJ, Delitto A (2006) Spinal stenosis: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res 443: 198-207.

- Baker AR, Collins TA, Porter RW, Kidd C (1995) Laser Doppler study of porcine cauda equina blood flow. The effect of electrical stimulation of the rootlets during single and double site, low pressure compression of the cauda equina. Spine 20(6): 660-664.

- Katz JN and Harris MB (2008) Clinical practice. Lumbar spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med 358(8): 818-825.

- Johnsson KE, Rosén I, Udén A (1992) The natural course of lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 279: 82-86.

- Johnsson KE, Udén A, Rosén I (1991) The effect of decompression on the natural course of spinal stenosis. A comparison of surgically treated and untreated patients. Spine 16(6): 615-619.

- Suri P, James Rainville, Kalichman L, Katz JN (2010) Does this older adult with lower extremity pain have the clinical syndrome of lumbar spinal stenosis? JAMA 304(23): 2628-2636.

- Kaiser MC, Capesius P, Roilgen A, Sandt G, Poos D, et al. (1984) Epidural venous stasis in spinal stenosis. CT appearance. Neuroradiology 26(6): 435-438.

- Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW (1990) Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 72(3): 403-408.

- Boos N, Weissbach S, Rohrbach H, Weiler C, Spratt KF, et al. (2002) Classification of age-related changes in lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine 27(23): 2631-2644.

- Miller J, Schmatz C, Schultz AB (1988) Lumbar disc degeneration: Correlation with Age, Sex, and Spine Level in 600 Autopsy Specimens. Spine 13(2): 173-178.

- Zindrick MR, Wiltse LL, Widell EH, Thomas JC, Holland WR, et al. (1986) A biomechanical study of intrapeduncular screw fixation in the lumbosacral spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 203: 99-112.

- Santiago FR, Milena GL, Herrera RO, Romero PA, Plazas PG (2001) Morphometry of the lower lumbar vertebrae in patients with and without low back pain. Eur Spine J 10(3): 228-233.

- Swanson KE, Lindsey DP, Hsu KY, Zucherman JF, Yerby SA (2003) The effects of an interspinous implant on the intervertebral disc pressure. Spine 28(1): 26-32.

- Haig AJ, Geisser ME, Tong HC, Yamakawa KS, Quint DJ, et al. (2007) Electromyographic and magnetic resonance imaging to predict lumbar stenosis, low-back pain, and no back symptoms. J Bone Joint Surg Am 89(2): 358-366.

- McCombe PF, Fairbank JC, Cockersole BC, Pynsent PB (1989) Reproducibility of physical signs in low-back pain. Spine 14(9): 908-918.

- Inufusa A, An HS, Lim TH, Hasegawa T, Haughton VM, et al. (1996) Anatomic changes of the spinal canal and intervertebral foramen associated with flexion-extension movement. Spine 21(21): 2412-2420.

- Watanabe R and Wesley W Parke (1986) Vascular and neural pathology of lumbosacral spinal stenosis. J Neurosurg 64(1): 64-70.

- Porter RW, Ward D (1996) Cauda equina dysfunction. The significance of two-level pathology. Spine 17(1): 9-15.

- Geisser ME, Haig AJ, Tong HC, Yamakawa KS, Quint DJ, et al. (2007) Spinal canal size and clinical symptoms among persons diagnosed with lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin J Pain 23(9): 780-785.

- Denard PJ, Holton KF, Miller J, Fink HA, Kado DM, et al. (2010) Lumbar spondylolisthesis among elderly men: prevalence, correlates, and progression. Spine 35(10): 1072-1078.

-

Yasir A Mohamed elhassan, Anas O Ahmed, Qurashi M Ali, Siddig Omer M Handady. Clinical Presentation of Lumbosacral Spinal Canal Stenosis Among Sudanese Patients. Glob J Ortho Res. 1(3): 2019. GJOR.MS.ID.000512.

-

Spinal canal Stenosis, Numbness, Lumbosacral stenosis, Sudanese patients, Vertebral body, Spondylolisthesis, Spinal canal narrowing, Squatting, Radiologist, Hypertrophy, Ligamentum flavum, Neurogenic claudication, Neurosurgery, Demographic Data, Musculoskeletal tissues, Intrathecal pressures

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.