Research Article

Research Article

Clinical Implications and Treatment Algorithm for Patients with de Quervain’s Tenosynovitis

William M Pearson1* and Obinwanne Ugwonali2

1Ashley A Ellingwood, Ryan P McGovern, USA

2Peachtree Orthopedics, 3200 Downwood Circle NW, Suite 700, Atlanta, GA 30327, USA

Corresponding AuthorWilliam M Pearson, Ashley A Ellingwood, Ryan P McGovern, USA

Received Date: May 23, 2022; Published Date: June 23, 2022

Abstract

Purpose: De Quervain’s tenosynovitis can be a debilitating condition affecting the first dorsal compartment of the wrist. Depending on the

severity, patients experiencing this pathology often lose significant functionality in the affected wrist. Upon diagnosis, non-surgical treatment is the

standard of care, but failure of conservative treatments can lead to the need for surgical intervention. The main purpose of this study was to report

the clinical implications and treatment algorithm for patients presenting with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. The secondary purpose was to report

clinical differences in patients that chose surgical intervention following conservative management for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis.

Methods: Following initial consultation with the treating orthopedic surgeon and throughout the conservative management time frame, 240

injuries (93%) were splinted, 230 (89%) patients were given an oral NSAID, and patients spent an average of 12 ± 6.9 weeks in occupational therapy

for treatment of their injuries. In addition, 165 (64%) received an initial cortisone injection into the first dorsal extensor tendon compartment of the

wrist. 44-Forty-four (17%) of these patients received a second cortisone injection, and 6 (2%) received a third cortisone injection with at least 2 to

3 months between each injection.

Result: Our study found that following conservative management there was significant improvement in the severity of symptoms, which was

recorded using visual analog scale (VAS) scores. However, 58 (22%) patients converted to surgical release for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, reported

a higher post-management severity of symptoms (p<.001) than the patients who were solely treated conservatively.

Conclusions: Patients showed significant improvement following conservative treatment, such as splinting, NSAIDs, occupational therapy and

corticosteroid injections. This study also confirms that patients who are surgically treated are associated with higher pain levels post-conservative

treatment and post-management than those solely treated conservatively. Finally, this data suggests that those patients in this patient population

who experience de Quervain’s tenosynovitis through traumatic onset are more likely to require surgical intervention.

Keywords: De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis; Conservative Treatment; Treatment Algorithm; Clinical; Hand and Wrist

Abbreviations: Splinting: thumb spica splinting; NSAIDs: Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs; OT: Occupational Therapy

Introduction

A common wrist pathology, de Quervain’s tenosynovitis is caused by a stenosing or thickening of the first dorsal compartment of the wrist.3 Resistance to gliding of the abductor pollicis longus and/or extensor pollicis brevis tendons within the narrowed and stiffened canal is what ultimately produces the characteristic radial sided wrist pain and decrease in motion [1]. This pain is often severe and can significantly hinder a patient’s productivity at work and in everyday life.

Conservative treatment is the first course of action upon diagnosis of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. The most common steps taken are to place the patient in a thumb spica splint and to prescribe anti-inflammatory medications in order to reduce inflammation and limit the consequent pressure on the tendons. However, upon removal of the splint, patients’ symptoms can sometimes return as they resume normal use of their wrist. Occupational therapy is commonly utilized to increase a patient’s function and strength. Corticosteroid injections are often recommended in moderate to severe clinical cases. In those patients that conservative treatment fails, surgical treatment can be recommended. The procedure involves releasing the first dorsal compartment in-line with the thumb extensor tendons within the first dorsal compartment [1-4].

The main purpose of this study was to report the clinical implications and treatment algorithm for patients presenting with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. The secondary purpose was to report clinical differences in patients that chose surgery following conservative management for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis.

Methods

Patient Selection

A retrospective chart review was performed on prospectively collected information of patients treated non-surgically and surgically for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis by a single expert orthopaedic surgeon (***) within a private orthopaedic group from August 1, 2014, to November 1, 2020. Protocol approval was granted, and oversight for this project was provided by the (***) IRB. Inclusion criteria for patients included in the current study are as follows: a clinical diagnosis of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis reported in the electronic medical record “Athena”; an x-ray record for the affected wrist. Exclusion criteria for this study included: only being seen by the treating physician as an IME (Independent Medical Examination); previous de Quervain’s tenosynovitis release surgery by another physician. All patients diagnosed with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis by the treating physician are included in this study and all were treated with the same treatment algorithm.

Clinical Evaluation

Diagnosis of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis begins with patient reported symptoms. Those that describe pain at the first dorsal compartment or radial aspect of the wrist with use or movement of the hand, specifically ulnar deviation, were further evaluated. Sensitivity to touch in this area is a further indication of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. In addition, the Finkelstein’s test is used to confirm a case of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. The Finkelstein test is performed by having a patient place their thumb into their fist and ulnarly deviate their wrist. Significant pain at the radial styloid with this movement is a strong indication of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis [5]. Along with clinical examination, patients are imaged with an anterior posterior (AP), lateral and oblique view of the wrist. Radiographic images were taken by a certified x-ray technician and reviewed by the treating orthopaedic physician (***) or nurse practitioner (***). Providers inspect the images in order to rule out other pathologies visible in an x-ray image, such as a pathologic bone process or an osteophyte that may be causing pain. Lack of visible pathologies increases the probability that the patient’s pain is due to de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. Patients are encouraged to begin conservative treatment upon diagnosis [3].

Conservative Management

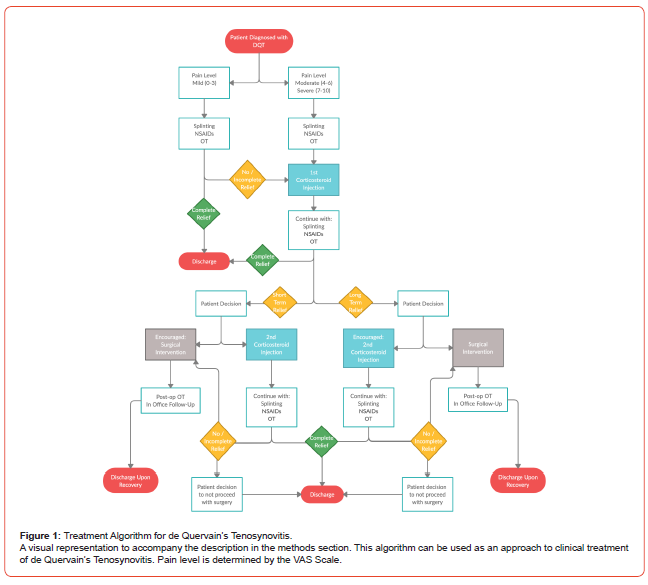

All patients are treated in the same manner unless they are unable to receive a certain type of treatment due to health concerns or they willingly refuse the suggested treatment course. Figure 1 provides a visual layout for the following treatment algorithm. After the initial evaluation and de Quervain’s tenosynovitis diagnosis, patients are first treated conservatively with splinting, NSAIDs and occupational therapy. The appropriate splint is a thumb spica splint, for which the patient is fitted by a certified athletic trainer. The patient is directed to wear the splint at all times for four weeks. Following the four-week period, they are instructed to gradually decrease their use of the splint as tolerated with their pain level. This gradually reintroduces movement and use of the injured tendons [3,4]. It should be noted that a study by Harvey et al. suggests that immobilization is not necessary with corticosteroid injections and that mobilization was encouraged [5]. All patients in this study were encouraged to wear a thumb spica splint by the treating orthopaedic surgeon based on his personal treatment protocol. Patients are encouraged to wear the splint for a few weeks until their pain subsides.

The treating orthopaedic surgeon (***) also prescribes NSAIDs for all diagnosed patients. Initially they are given one 15 mg meloxicam tablet daily. In the occasion that a patient has had an adverse reaction to meloxicam or it has proven ineffective for them in the past, the treating orthopaedic surgeon prescribes celecoxib 200 mg at 1 tablet every 12 hours in substitution of meloxicam [3,5].

For occupational therapy, the patient is referred to a certified hand therapist for 2 sessions a week for 6 weeks. In these therapy sessions, therapists are instructed to focus on massaging the affected area and to work on increasing strength and both active and passive ROM in the affected wrist [3,5].

Patients are encouraged to return to the office every 6 weeks for reevaluation, or as dictated by symptom severity. If the patient’s VAS score and symptom severity do not improve over the 6-week period, it is an indication that the conservative treatments provided were ineffective. It is possible that the patient may experience complete/partial relief for months at a time before the symptoms return, leading to a larger gap between follow-up appointments. At any point, if the patient experiences satisfactory relief with these conservative treatments, they are discharged from the physician’s care. This may be done formally through a follow-up appointment or is indicated by the patient choosing not to return for further treatment.

Corticosteroid injections can be an effective tool for reducing inflammation in patients with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis [3]. At the initial visit and upon diagnosis, patients with a VAS score of moderate to severe (see “Clinical Outcomes’’ for description of VAS scale) are offered the option to receive their first corticosteroid injection. They may however choose to proceed with the previously stated treatment options before receiving an injection.

The injection is performed by injecting a solution of 1cc of 1% Lidocaine HCl Injection, USP 300mg/30mL (10mg/mL), 1cc of 0.25% Bupivacaine Hydrochloride Injection, USP 75mg/30mL (2.5mg/mL), and either 1cc of Methylprednisolone Acetate Injectable Suspension USP 40mg/mL or 1cc of Celestone Soluspan (betamethasone sodium phosphate and betamethasone acetate) Injectable Suspension, USP 30 mg/5mL (6mg/mL) to the base of the thumb at the first dorsal compartment of the wrist with a short 25 gauge needle.

Methylprednisolone is given to patients with Caucasian complexion, and Celestone Soluspan is given to patients of color. This is to avoid blanching discoloration of the patient’s skin caused by Methylprednisolone [7-9]

Patients with a mild VAS score at their initial visit are only offered an injection at their second office visit when it is clear that the splinting, NSAIDs, and therapy treatments did not provide any symptom relief on their own. In the time period following the first corticosteroid injection, the patient is instructed to continue the other conservative treatments (splinting, NSAIDs, and therapy).

At the follow-up appointment after the first corticosteroid injection, a patient’s de Quervain’s symptoms are reevaluated. At this time, the patient self-reports the effectiveness of the injection paired with the other conservative treatments. If the patient reports no relief or short-term relief (less than 6 weeks of symptom relief) and their symptoms have since returned, surgical intervention in encouraged. Patients may sometimes choose a second corticosteroid injection in order to try to avoid surgical intervention. Similar to the first injection, patients are instructed to continue with conservative treatment following the second injection. The treating physician requires a minimum of two months between corticosteroid injections. If the patient opts for a second injection and their symptoms return, surgical intervention is again recommended. If the patient declines surgical intervention at this time, they are often discharged from the physician’s give n the risk of tendon rupture with multiple cortisone injections [9-11].

If the patient reports long-term relief (greater than 6 weeks of symptom relief) from the first injection, a second corticosteroid injection in encouraged if their symptoms return. The second injection protocol is identical to the first. Surgical intervention is often not recommended in this situation although some patients may choose to proceed with surgery instead of receiving another cortisone injection. The patient is instructed to continue with the other conservative treatments following the second injection. If the patient does not experience satisfactory symptom relief following the second injection, surgical intervention is recommended. The patient is discharged from the physician’s care if he/she does not choose to proceed with surgical intervention.

Due to the weakening effect of the corticosteroid injections, the orthopedic surgeon does not offer a third injection to the same area because of the increased risk of spontaneous tendon Rupture [10- 12] (Figure 1).

Intraoperative Technique

Patients that are recommended for surgical intervention are guided through standard preoperative planning and approval. Typically done under general anesthesia, the treating orthopaedic surgeon releases the affected first dorsal compartment as described by Ilyas et al. The incision site is closed with suture and covered with a bandage.15,18 It should be noted that Ilyas et al. states that they perform this procedure under local anesthesia.15 (***) will perform this procedure under general, local, and MAC anesthesia, dependent upon the wishes of the patient. It is possible that a higher-than-normal percentage of patients in this population choose general anesthesia because they have had a traumatic injury. Traumatic injuries may cause increased sensitivity of adjacent tissue in addition to their de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, and therefore to be in more pain and under greater stress. These factors may increase the desire for general anesthesia.

Post-Operative Care

After surgery, patients that do not have Penicillin allergies are required to take one keflex 500 mg tablet every 6 hours for the first 24 hours following the operation. This amounts to a total of 4 tablets which are prescribed to the patient prior to surgery. The ASHP guidelines and a few other reports state that prophylactic antibiotic use for clean hand procedures is not indicated [13-19]. However, because of the treating physician’s goal preventing all infection, prophylactic antibiotics are prescribed. Both methods of operation should be considered as acceptable.

For postoperative pain management, patients are initially prescribed 30 tablets of hydrocodone 7.5 mg-acetaminophen 325 mg to be taken every 6 hours or as needed. If the patient requests or requires a weaker narcotic for post-operative pain management, the patient may be given a prescription on the day of surgery for 30 tablets of tramadol 50 mg to be taken every 6 hours or as needed. Patients are encouraged to wean off narcotic pain medication as soon as they can comfortably do so. It should be noted that recent CDC guidelines does not recommend postoperative opioid analgesics for surgical procedures in this category. If opioids are indicated, they recommend no more than a 3-day supply [20]. Similar to the thought process behind the use of general anesthesia, many patients in this population have experienced some traumatic event that has led to their de Quervain’s tenosynovitis. Because of this, they tend to have higher pain levels and are under greater stress, and therefore increases the need for stronger pain-relieving medication. There is much support for significantly reducing the prescription of opioid medication across the board, and we agree with this statement. The described pain management is the traditional protocol originally followed by this practice, but this protocol is actively being revised and monitored in accordance with recent evidence. Post-operative pain for a surgery involving only a de Quervain’s release can be managed with NSAIDs. However, patients in this population often undergo surgeries involving multiple procedures increasing their post-operative pain levels and need for opioid medication.

Patients were required to return to the office 10-14 days after surgery. During this appointment, the nurse practitioner or certified athletic trainer removes the patient’s sutures and cleans the incision site. After this visit, the patient is cleared to begin therapy with a certified hand therapist twice a week. The treating orthopaedic surgeon recommends immediate active and passive ROM therapy with no restrictions in order to regain strength and ROM lost with surgery. Patients are encouraged to continue to follow up in office every 6 weeks so that recovery progress, pain level, and symptom severity can be monitored [1]. If significant pain persists, patients can be prescribed pain medication for up to 90 days following surgery, after which they are referred to a pain management specialist.

Clinical Outcomes

A visual analog scale (VAS) was used to collect a measurable pain level (0, no pain; 10, worst imaginable pain) for each patient. This was taken by a clinical assistant at the initial consultation and following any conservative management and surgical intervention. The treating orthopaedic surgeon categorized each patient’s pain severity as mild (VAS, 0-3), moderate (4-6), or severe (7-10) to give insight into the patient’s improvement and therefore differentiate the appropriate treatment pathway demonstrated in the treatment algorithm (Figure 1). Additionally, to assess the patient’s improvement, the treating orthopaedic surgeon will subjectively evaluate the patient’s ability to return to their normal activities of daily living. For instance, can the patient pick up a cup of coffee or their child without pain [21-24].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis for patient demographics and pertinent medical information were performed. Pre- and postoperative comparisons between the surgical and non-surgical groups were analyzed using t-tests, chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the category of data. All statistical analysis was performed with an a-priori alpha set of p<.05. All data was analyzed using a common statistical software program (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 25, Armonk, NY).

Result

Patient Result

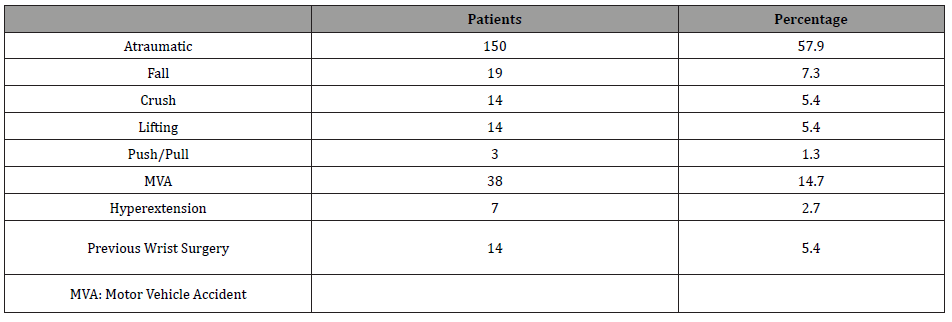

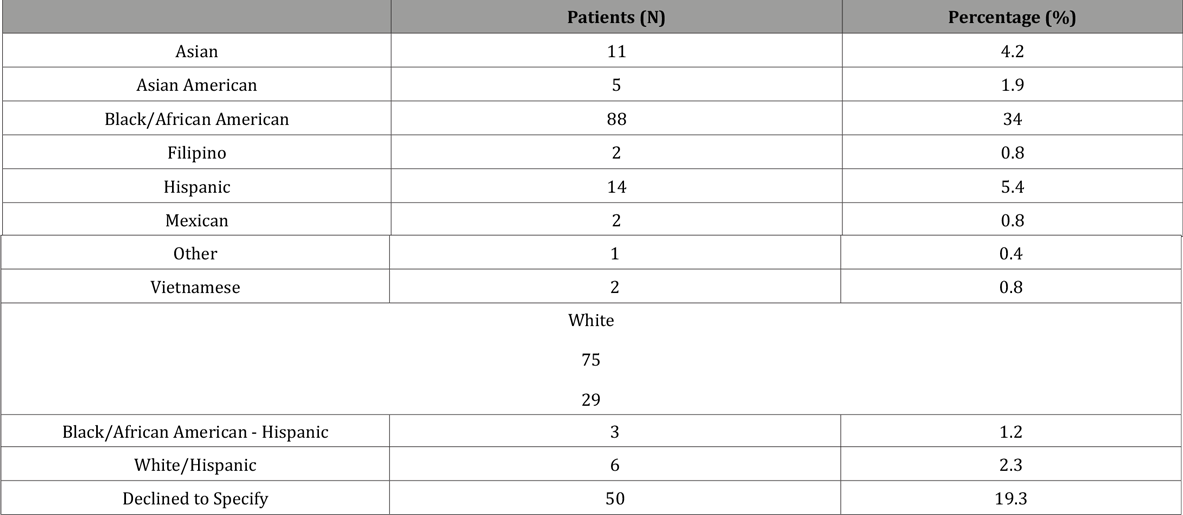

After administering the inclusion criteria, 243 (190 female and 53 male) patients with 259 injuries were eligible to be included in this study with a mean age of 43.9 ± 11.8 years (mean ± SD) and BMI of 29.6 ± 7.1 at the time of initial consultation with the treating orthopaedic surgeon. Most injuries reported an atraumatic onset (58%), however various mechanisms of traumatic injuries were reported and are presented in Table 1. One hundred and forty-one (54%) involved the right hand, while 118 (46%) involved the left. Upon radiographic evaluation, these patients presented with a mean radial inclination of 23.5 ± 3.4 mm and radial height of 12.2 ± 7.2 mm. The injuries included in this study were from a diverse background with racial demographics presented in Table 2. Most patients reported no comorbidities (56%), although 81 (31%) were classified as obese (BMI>30), 8 (3%) patients had diabetes and 4 (2%) reported a previous diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. A total of 204 (79%) of patients reported never smoking, while 30 (12%) patients were classified as former smokers, 12 (5%) patients were light smokers, 9 (4%) were moderate smokers and 4 (2%) were heavy smokers at time of evaluation [25-27].

Table 1: Mechanism of Injury

Table 2: Racial Demographics.

Following initial consultation with the treating orthopedic surgeon, 240 injuries (93%) were splinted to limit motion at the thumb and wrist. Based on the treatment algorithm previously presented, 165 (64%) received an initial cortisone injection to the first dorsal extensor tendon compartment of the wrist, 44 (17%) of these patients received a second cortisone injection, and 6 (2%) received a third cortisone injection. Additionally, 230 (89%) patients were given an oral NSAID (***) during the conservative management timeframe. For the 259 reported injuries, patients spent an average 12 ± 6.9 weeks in occupational therapy for treatment of their injuries. Following conservative management patients were seen in the treating orthopaedic surgeon’s office for follow-up at an average 14 ± 2.8 weeks following initial consultation. 201 (78%) of 259 injuries were released from follow-up care, with 58 (22%) converted to surgical release for de Quervain’s Tenosynovitis (Tables 1&2).

Clinical Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

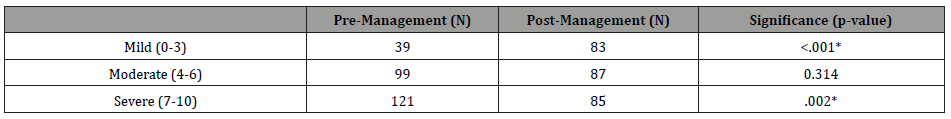

Following conservative management patients reported VAS scores of 4.9 ± 2.9, which was a significant improvement (p<.001) from initial VAS scores of 6.1 ± 2.4 upon initial consultation. Changes in initial severity of symptoms and post-conservative management are reported in Table 3. An increase in patients reporting mild symptoms after conservative management demonstrated a significant improvement (p<.001) from 39 injuries initially to 83 injuries after treatment. Additionally, a significant decrease (p=.002) in patients reporting severe symptoms demonstrated improvement from 121 injuries to 85 injuries following conservative management. Four (1%) injuries were lost to followup for reporting VAS and severity levels following conservative management.

Table 3: Severity of Symptoms.

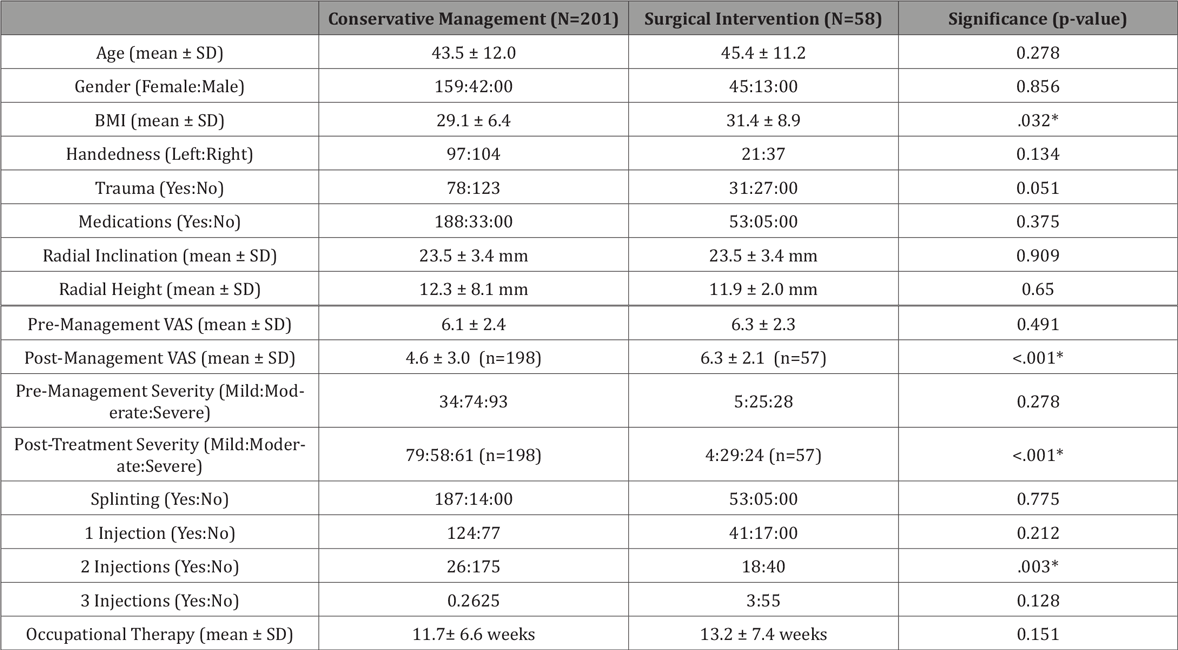

As previously reported, 201 (78%) injuries were treated with only conservative management and 58 (22%) injuries progressed to surgical intervention. Demographic and clinical comparisons between the non-surgical and surgical groups are presented in Table 4. The patients that underwent surgical release for de Quervain’s tenosynovitis had significantly higher BMI’s (p=.032), higher post-conservative management VAS (p<.001) scores, higher post-management severity of symptoms (p<.001) and were more likely to have undergone a second cortisone injection during their conservative management time period (p=.003).

Table 4: Post-Conservative Management Demographics.

For the 58 patients with a traumatic onset of symptoms, 53% (31/58) underwent surgical intervention while 47% (27/58) participated in only conservative management for their injuries. These patients who had traumatic onset of symptoms demonstrated significantly higher VAS scores on initial evaluation (6.5/10 vs 5.8/10, p=.026) when compared to those with nontraumatic onsets, respectfully, as well as with mean change in VAS from pretreatment to posttreatment (-1.6 vs. -0.8, p=.021). There was no significant difference between groups when comparing VAS scores following surgical intervention or conservative management (4.9 vs 5.0, p=.667 respectively) (Tables 3&4).

Discussion

Perhaps the most interesting finding from this study, is that those patients who were traumatically injured and consequently developed de Quervain’s tenosynovitis had a higher likelihood of undergoing a surgical release. Although not technically statistically significant (p=.051), fifty-three percent (31/58) of injuries that received surgical intervention developed de Quervain’s tenosynovitis symptoms following a traumatic event. On the contrary, 39% (78/201) of injuries that received only conservative treatment developed symptoms as a result of a traumatic event. This is a possible indication that serious traumatic events can lead a patient to be predisposed to surgical intervention. This correlation however could be skewed by the fact that this patient population has a high incidence of traumatic injury as (***) sees many patients that are injured in either a motor vehicle or workplace accident.

It is interesting to note that the surgical outcomes of the patients were significantly worse than those in previously published literature. Ilyas et al. in 2007 reported a surgical intervention “cure rate” of greater than 91%.15 Similarly, Garcon et al. in 2018 stated that of 80 surgical cases, patients experienced total functional impairment regression in 85% of those cases10 It does not state in these reports the circumstances of the patients’ injuries. Traumatic injury events often create multiple injuries. As a result, the treatment of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis injury may be impacted by the other injuries present. Often a de Quervain’s release surgery is accompanied by several other procedures in the affected wrist. As is common with surgical outcomes, the more intraoperative work that is done, the more healing involved and the less likely a perfect outcome will be achieved. It is for this reason that the surgical outcomes expressed in this study may be less than perfect than those reported by Ilyas and Garçon.10,15 However it should be noted that despite these external factors affecting patient outcomes, the conservative treatment algorithm outlined in Figure 1 still lead to an improvement of patient symptoms and a decrease in VAS scores.

As a part of this study, patient’s initial radiographic images of the effected wrist were examined and evaluated for radial height and inclination. After statistical evaluation, there was no evidence of a relationship between these factors and the severity of disease or need for surgical intervention.

In addition, this study provides more evidence for the theory that conservative nonsurgical treatments are the most effective at reducing a patient’s pain level and symptom severity when suffering from a de Quervain’s tenosynovitis injury. This study was able to demonstrate that the treatment algorithm displayed in Figure 1 is an effective treatment approach for dealing with de Quervain’s tenosynovitis and was shown to lead to a decrease in patient VAS scores in the majority of cases. Early and consistent conservative treatment appears to be the best course of action to give patients the greatest chance of improvement. The treatment suggested here is based on the experience of a single physician and his patient population which may have a higher percentage of traumatically induced de Quervain’s tenosynovitis and therefore may be considered controversial. However, the algorithm presented here can be used as a tool for both young and experienced physicians to guide their treatment decision making process, when dealing with a patient population with a large number of traumatically-induced de Quervain’s tenosynovitis.

Goel et al. in 2014, Ilyas et al. in 2007, and other articles outline the rehabilitative options including both conservative and surgical for the treatment of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis.3,10,11,15 Modes of treatment are consistent across these reports. Conservative treatments are the same as those outlined in this study. Thumb spica splinting, oral anti-inflammatory medications, occupational therapy, and corticosteroid injections are universally employed. These studies however do not provide a timeline or framework for how to use these methods. This study takes these treatment methods and suggests a way in which to use them. Physicians of all kinds can use this framework to guide their decision making, and to serve a building block as they develop their own methods to serve their patient population through their clinical experience.

Conclusion

Patients showed significant improvement following conservative treatment, such as splinting, NSAIDs, occupational therapy and corticosteroid injections. This study also supports that patient who are surgically treated are associated with higher pain levels post-conservative treatment and post-management than those solely treated conservatively. Finally, this data suggests that those patients in this patient population who experience de Quervain’s tenosynovitis through traumatic onset are more likely to require surgical intervention.

Limitations

There are limitations in this study that need to be considered when interpreting the results. Because this was a retrospective study utilizing chart review, we were unable to inquire additional information on patients that were lost to follow-up. In addition, while it is standard practice to gather information such as pain level, patient charts were not created with the intent to populate a statistical study, and therefore may be slightly inconsistent. Furthermore, the visual analog pain scale was self-reported by the patient, so there is the possibility of inconsistency

Legend

• Green Diamonds complete relief determination

• Yellow Diamonds - incomplete relief determination

• Red Ovals - discharge from car

• Light Blue Squares - corticosteroid injection

• Grey Square - surgical intervention

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no financial disclosures and/or conflicts of interests for any of the authors involved in the making of this manuscript.

References

- Goel R, Abzug J (2015) de Quervain’s tenosynovitis: a review of the rehabilitative options. Hand (N Y) 10(1): 1-5.

- Allbrook V (2019) The side of my wrist hurts: De Quervain’s tenosynovitis. Australian Journal of General Practice 48(11): 753-756.

- Ilyas A, Ast M, Schaffer A, Thoder J (2007) de Quervain tenosynovitis of the Wrist. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons 15(12): 757-764.

- Jinhee O, Messing S, Hyrien O, Hammert W (2017) Effectiveness of Corticosteroid Injections for Treatment of de Quervain’s Tenosynovitis. Hand (N Y) 12(4): 357-361.

- Courtney Dawson, Chaitanya S Mudgal (2010) Staged Description of the Finkelstein Test. The Journal of Hand Surgery 35(9): 1513-1515.

- Harvey FJ, Harvey PM, Horsley MW (1990) De Quervain's disease: surgical or nonsurgical treatment. J Hand Surg Am 15(1): 83-87.

- Skarmeta NP, Hormazabal FA, Alvarado J, Rodriguez AM (2017) Subcutaneous Lipoatrophy and Skin Depigmentation Secondary to TMJ Intra-Articular Corticosteroid Injection. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 75(12): 2540.e1-2540.e5.

- van Vendeloo SN, Ettema HB (2016) Skin depigmentation along lymph vessels of the lower leg following local corticosteroid injection for interdigital neuroma. Foot Ankle Surg 22(2): 139-141.

- Zhang B, Hu ST, Zhang YZ (2012) Spontaneous rupture of multiple extensor tendons following repeated steroid injections: a case report. Orthop Surg 4(2): 118-121.

- Gyuricza C, Umoh E, Wolfe SW (2009) Multiple pulley rupture following corticosteroid injection for trigger digit: case report. J Hand Surg Am 34(8):1444-1448.

- Yamada K, Masuko T, Iwasaki N (2011) Rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus tendon after injections of insoluble steroid for a trigger finger. J Hand Surg Eur 36(1): 77-78.

- Nguyen ML, Jones NF (2012) Rupture of both the abductor pollicis longus and extensor pollicis brevis tendons after steroid injection for de quervain tenosynovitis. Plast Reconstr Surg 129(5): 883e-886e.

- Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, Trish M Perl, Paul G Auwaerter, et al. (2013) Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health-Syst Pharm 70(3): 195-283.

- Dunn JC, Means KR, Desale S, Giladi AM (2020) Antibiotic Use in Hand Surgery: Surgeon Decision Making and Adherence to Available Evidence. Hand (N Y) 15(4): 534-541.

- Johnson SP, Zhong L, Chung KC, Waljee JF (2018) Perioperative Antibiotics for Clean Hand Surgery: A National Study. J Hand Surg Am 43(5): 407-416.e1.

- Murphy GR, Gardiner MD, Glass GE, Kreis IA, Jain A, et al. (2016) Meta-analysis of antibiotics for simple hand injuries requiring surgery. Br J Surg 103(5): 487-492.

- Platt AJ, Page RE (1995) Post-operative infection following hand surgery. Guidelines for antibiotic use. J Hand Surg Br 20(5): 685-690.

- Sandrowski K, Edelman D, Rivlin M, Jones C, Wang M, et al. (2020) A Prospective Evaluation of Adverse Reactions to Single-Dose Intravenous Antibiotic Prophylaxis During Outpatient Hand Surgery. Hand (N Y) 15(1): 41-44.

- Tosti R, Fowler J, Dwyer J, Maltenfort M, Thoder JJ, et al. (2012) Is antibiotic prophylaxis necessary in elective soft tissue hand surgery? Orthopedics 35(6): e829-833.

- (2018) Bree Collaborative. Prescribing Opioids for Postoperative Pain-Supplemental Guidance.

- Abi-Rafeh J, Kazan R, Safran T, Thibaudeau S (2020) Conservative Management of de Quervain Stenosing Tenosynovitis: Review and Presentation of Treatment Algorithm. Plast Reconstr Surg 146(1): 105-126.

- Akhtar M, Faraz Ul Hassan Shah Gillani S, Nadeem RD, Tasneem M (2020) Methylprednisolone acetate injection with casting versus casting alone for the treatment of De-Quervain's Tenosynovitis: a randomized controlled trial. J Pak Med Assoc 70(8): 1314-1318.

- Carreira D, Chao J (2018) Opioid Use After Surgical Treatment for Ankle Fractures: An Observational Report and Risk Factor Analysis. Peachtree Orthopedics.

- Foldvari-Nagy L, Takacs J, Hetthessy JR, Mayer AA, Szakacs N, et al. (2020) Treatment of De Quervain's tendinopathy with conservative methods. Orv Hetil 161(11): 419-424.

- Garcon J, Charruau B, Marteau E, Laulan J, Bacle G (2018) Results of surgical treatment of De Quervain’s tenosynovitis: 80 cases with a mean follow-up of 9.5 years. Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research 104(6): 893-896.

- Hoffman RD, Adams BD (1998) The role of antibiotics in the management of elective and posttraumatic hand surgery. Hand Clin 14(4): 657-666.

- Mangukiya HJ, Kale A, Mahajan NP, Ramteke U, Manna J (2019) Functional outcome of De Quervain's tenosynovitis with longitudinal incision in surgically treated patients. Musculoskelet Surg 103(3): 269-273.

-

William M Pearson and Obinwanne Ugwonali. Clinical Implications and Treatment Algorithm for Patients with de Quervain’s Tenosynovitis. Glob J Ortho Res. 3(5): 2022. GJOR.MS.ID.000575. DOI: 10.33552/GJOR.2022.03.000575.

-

De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis, Conservative Treatment, Treatment Algorithm, Clinical, Hand, Wrist, Splinting, Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs, Occupational Therapy

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.