Case Report

Case Report

From Canis to Multocida: Genetic Identification of a Misclassified Pasteurella Strain

Ghada Blel1, Salma Abbes1, Emna Achich1, Mohamed Ali khelif2, Khaled Zitouna2, Maher Barsaoui2 and Meriam Zribi1*

1Microbiology laboratory, University Hospital La Rabta, Tunisia

2Orthopedics department, University Hospital La Rabta, Tunisia

Corresponding AuthorMeriam Zribi, Microbiology laboratory, University Hospital La Rabta, Tunisia

Received Date:April 29, 2025; Published Date: May 09, 2025

Abstract

Pasteurella spp is a Gram-negative coccobacillus belonging to the Pasteurellaceae family, commensal to the oral cavity, oropharynx, or intestine of domestic animals. The majority of human infections caused by Pasteurella spp. are associated with dog and cat bites, sometimes with bites from other animals or contact with animals without bites or scratches. P. canis is a rare pathogen that can cause various infections: skin and soft tissue infections, arthritis, osteomyelitis, respiratory tract infections, ocular infections, bacteremia, and others. We report the case of a 64-year-old man admitted to the orthopedics department for a phlegmon of the hand. The wound was due to a bite from a stray cat and presented as two foci on the dorsum of the left hand with purulent discharge. The patient underwent surgical debridement of the wound, and three intraoperative swabs from the wound were sent to the microbiology laboratory.

Subculture after 24 hours isolated small gray colonies on blood agar and chocolate agar. Gram staining showed Gram-negative coccobacilli. Catalase, and oxidase were positive. The Vitek GN identified P. canis. However, further genomic analysis demonstrated that the initial identification was incorrect, confirming the isolate as P. multicide. The bacterium was susceptible to beta-lactams, nalidixic acid, fluoroquinolones, as well as tetracycline and doxycycline. The patient was treated with amoxicillin-clavulanate and doxycycline postoperatively and was discharged following a favorable outcome.

Keywords:Pasteurella SPP; soft tissue infection; DNA sequencing

Introduction

Animal bites are a common source of injury in humans, with dog bites being the most frequent accounting for 60% to 90% of cases, followed by cat bites (5%-20%) [1] Notably, despite often appearing as superficial puncture wounds, injuries resulting from cat bites can result in serious complications such as cellulitis, tenosynovitis, endocarditis, osteomyelitis, abscess, meningitis, tendon rupture, and nerve injury. Dog and cat bite infections are generally polymicrobial, Pasteurella species represent the most common bacterial isolates. In dog bite infections, P.canis was the predominant species, accounting for 50% of isolates. Similarly, Pasteurella was highly prevalent in cat bite infections (75%), with P.multocida subspecies multocida and septica being the most frequently identified [2]. We present a case of soft tissue infection resulting from a cat bite, highlighting the identification process of P. multocida, which was initially and incorrectly classified as P. canis. We discuss the diagnostic procedures and methodologies employed in this case.

Case presentation

A 64-year-old man with no significant medical history presented to the emergency department at University Hospital La Rabta, Tunisia, with swelling and extensive erythema on his left hand. He reported a cat bite two days prior and subsequently received a prophylactic rabies vaccine following a dispensary consultation. The patient was later referred to the orthopedics department. Upon clinical examination, he was systemically well and in a clear state of consciousness, his vital parameters were as follows: blood pressure – 130/70 mmHg, pulse – 86 beats/min, he exhibited normal breathing with an arterial oxygen saturation level of 93% and no fever was detected. Lab work showed a C-reactive protein of 159.2 mg/L and white blood cell count of 20.39x103 /uL with neutrophilia (15.53 x103 /uL). Furthermore, the examination revealed a swollen, erythematous hand with tenderness to palpation. A phlegmon was located on the dorsum of the left hand as well as two punctiform animal bite wounds with purulent discharge (Figure 1). A hand X-ray was conducted (Figure 2), followed by surgical debridement. Three intraoperative swabs were then collected from the wound and sent to our microbiology laboratory. The patient was discharged with a positive clinical response and prescribed a two-week postoperative course of oral amoxicillin-clavulanate and doxycycline, selected based on antimicrobial susceptibility profiles.

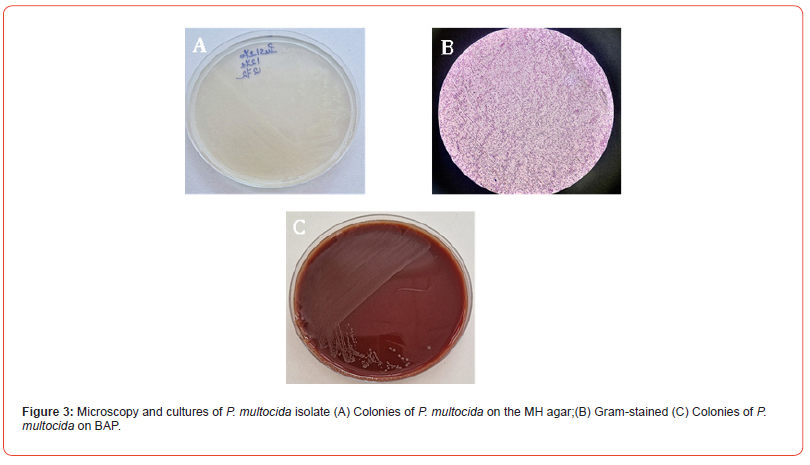

Microbiological testing, including Gram staining and cultures on a blood agar plate (BAP) with 5 % sheep blood, chocolate agar, Mueller-Hinton agar and eosin-methylene blue (EMB) agar, was performed. Following overnight incubation at 37°C, bacterial growth was noted on the blood, Mueller-Hinton and chocolate agars, but not on the EMB agar (Figure 3A, 3C). The blood agar colonies were very small, smooth, nonhemolytic, grayish-white (Figure 3C). Gram staining revealed Gram-negative coccobacilli (Figure 3B), and both catalase and oxidase were positive. The bacterial isolate was identified with a low discrimination level as P. canis by Vitek 2 COMPACT (bioMérieux, France) using GN ID cards. The antimicrobial susceptibility profile of the isolate was determined by the standard disk-diffusion method (Figure 4) and interpreted according to EUCAST guidelines (2023). The chromogenic beta-lactamase assay was negative.

The strain showed susceptibility to beta-lactams, nalidixic acid, fluoroquinolones, tetracycline, doxycycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Detailed and accurate identification of the bacterium was performed by nucleic acid-based methods. The strain was subjected to a 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing. Genomic DNA was prepared from cell pellets obtained from 5 ml of fresh overnight culture in broth medium. The DNA extraction was performed with the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An860-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the 16S primers 5 -ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT- 3′ and 5′-TTGACGTCRTCCMCACCTTCCTC-3[3]. Amplified 16s rDNA sequences were sequenced after amplification using the same primers by using Sanger technology. The PCR products were purified using Mini Elute purification kit (Qiagen, France) and submitted to bidirectional cycle sequencing with the Big Dye terminator V3.0 reaction kit. The sequencing reaction mixtures were analyzed by using an ABI 310 sequence analyzer with the Sequence Analysis software (Applied Biosystems, France). All ob tained sequences were blasted on line via NCBIwww.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov by using BLASTN software to find the best hit query sequences. Species identity was considered if identity percent was ≥98%. In our case, the genome of the tested strain was 99.86 % identical to reference strain P. multocida.

Discussion

The microbiology of human infections following animal bites is often complex and polymicrobial, involving a diverse range of aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. These bacteria predominantly reflect the oral microbiome of the biting animal, a composition that can be further affected by the animal’s diet, including prey and other food sources [4] .Pasteurella spp. represent a significant portion of the microbial flora isolated from the canine and feline oropharynx with isolation rates ranging from 12.5 to 87 percent in these animals, making them most common pathogen incriminated in both dog and cat bites [5].The spectrum of the clinical presentation of Pasteurella spp. infections ranges from uncomplicated soft tissue infections, as seen in our case, to severe osteoarticular infections and bacteremia [6,7]. A review published by Hazelton, et al. [8] details deep tissue contamination involving bone and/or joints among the pediatric population resulting from Pasteurella spp. infections. Complications associated to such injuries are usually linked with an immunosuppression state or underlying diseases such as diabetes, cirrhosis and autoimmune disorders [9]. In the presented case, the patient, with no significant underlying medical conditions, demonstrated a prompt and favorable clinical evolution of the hand following a surgical excision of the affected area, a drainage of the purulent collection and a course of appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Strain identification initially employed staining and in vitro cultivation on selective agars, alongside biochemicals profiling via the VITEK system. While phenotypic characteristics suggested P.canis , a species uncommonly isolated, we proceeded with genomic sequencing for confirmation, which instead identified the isolate as P. multocida. Prior literature has addressed this inconsistency, for example, Talan and al. reported in their studies an occasional discordance in species identification with four P. multocida isolates being identified as P. canis. The susceptibility profile observed in our case aligns with findings documented in the literature, being susceptible to beta-lactams, nalidixic acid, fluoroquinolones, tetracycline, doxycycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. In conclusion, P. multocida is a commonly isolated bacterium in infection associated with dog and cat bite. Identification using sequencing is more accurate and specific. Treatment of P. multocida infections include either surgical options or medical management and in some cases a combination of both.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Maniscalco K, Edens MA. (2025) Animal Bites. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- Talan DA, Citron DM, Abrahamian FM, Moran GJ, Goldstein EJ (1999) Bacteriologic analysis of infected dog and cat bites. Emergency Medicine Animal Bite Infection Study Group. N Engl J Med 340(2): 85‑

- Sting R, Eisenberg T, Hrubenja M (2019) Rapid and reasonable molecular identification of bacteria and fungi in microbiological diagnostics using rapid real-time PCR and Sanger sequencing. J Microbiol Methods 159: 148‑1

- Abrahamian FM, Goldstein EJC (2011) Microbiology of Animal Bite Wound Infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 24(2): 231‑2

- Holst E, Rollof J, Larsson L, Nielsen JP (2025) Characterization and distribution of Pasteurella species recovered from infected humans | Journal of Clinical Microbiology 30(11).

- Bruna N, Ana Garrido G, Carolina NC, Marta G, Ramona-Diana B (2021) Septic Arthritis and Bacteremia Due to Infection by Pasteurella canis. Cureus 13(11): e19478.

- Rohan PCaitlin H, Keerthi G, Priyal A, Tyler K et al., (2025) Rare Case of Pasteurella canis Bacteremia from Cellulitis. ResearchGate 9(8): 414-419.

- Hazelton BJ, Axt MW, Jones CA (2013) Pasteurella canis osteoarticular infections in childhood: review of bone and joint infections due to pasteurella species over 10 years at a tertiary pediatric hospital and in the literature. J Pediatr Orthop 33(3): e34-38.

- Hitkova HY, Hristova PM, Gergova RT, Alexandrova AS (2024) Pasteurella canis soft tissue infection after a cat bite – A case report. IDCases 36: e01963.

-

Ghada Blel, Salma Abbes, Emna Achich, Mohamed Ali khelif, Khaled Zitouna,et.all. From Canis to Multocida: Genetic Identification of a Misclassified Pasteurella Strain. Glob J Ortho Res. 5(1): 2025. GJOR.MS.ID.000602.

-

Pasteurella spp; soft tissue infection; DNA sequencing

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.