Review Article

Review Article

Key Components of A Motorcyclist Safety – Case Study Slovenia

Tomaž Tollazzi1*and Matej Moharić2

1Ph.D., University of Maribor, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Transportation Engineering and Architecture, Maribor, Slovenia

2Ph.D. student, University of Maribor, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Transportation Engineering and Architecture, Maribor, Slovenia

Tomaž Tollazzi, Ph.D., University of Maribor, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Transportation Engineering and Architecture, Maribor, Slovenia.

Received Date: May 29, 2020; Published Date: June 10, 2020

Abstract

Powered two-wheelers (PTWs) is a term used in the motorcycle industry that includes motorcycles, mopeds and scooters. PTWs are an economical means of transport that offer increased mobility in case of traffic jams, which is very popular in urban transport. In addition, riding a motorized two-wheeler offers a special feeling that is attractive to many riders. However, PTWs can also be considered as a vulnerable group of road users.

In last few years the total number of traffic accidents in Slovenia has decreased whilst the number of accidents involving powered two-wheelers (PTWs) has increased. In 2017, 104 people died in road accidents in Slovenia, the lowest number recorded in the last 60 years. In contrast, during the same year there was a noticeable increase in the number of PTW rider fatalities. By the end of 2017, there were 29 fatalities among PTW riders, which, in comparison to the previous year (2016, 24 fatalities), represents an increase of 21%. In 2017, the proportion of PTW fatalities was 24% out of all road accident fatalities, which is the worst Figure since records began in Slovenia. In addition, the proportion of PTW riders who were seriously injured or killed in comparison to the overall number that were seriously injured or killed in all traffic accidents was significantly higher than the proportion of PTW riders in the traffic structure.

Due to all of the above-mentioned data, it is clear that there is a significant interest in Slovenia in understanding the relations between motorcyclists and road infrastructure, to find some new approaches to design, equipping and maintaining roads.

In this paper an eye-tracking research is also presented, which was carried out with motorcyclists and personal car drivers. We applied a method based on visual analysis to study the gaze behavior of motorcyclists’ and personal car drivers. This method allows us to explore patterns and extract common eye movement strategies.

Consequently, we suggest some new measures for upgrading the level of motorcyclists’ traffic safety.

Keywords: Powered two-wheelers; Safety; Infrastructure; Measures; Eye-tracking

Introduction

Powered two-wheelers (PTWs) is a term in the motorcycle industry, which includes motorcycles, mopeds and scooters. PTWs represent an economical means of transport, offering increased mobility in traffic congestion, which is popular in urban commuting. In addition, riding a PTW provides a special sensation which is attractive for many riders.

The vulnerability of PTWs has been highlighted by the large number of traffic accidents and poor safety statistics in many European and worldwide countries. Motorcycles have very different road performance characteristics than other types of vehicles. Certain maneuvers and road conditions carry a higher risk to motorcyclists than to drivers. Consequently, PTW riders can also be considered as a vulnerable group of road users. Especially because they do not have a protective “shell”, the driving dynamics of two-track vehicles differ from the driving dynamics of a singletrack vehicles (two-track: steering wheel, one-track: handlebar and lean angle), consequently rider has some difficult handling tasks while controlling the motorcycle, in particular during cornering or braking maneuvers and even more so in emergency situations to mitigate or avoid incidents, low mass relative to other types of motorized participants (coming from the opposite direction), occupants of passenger cars are ’’passive’’, occupants on motorcyclist must be ’’active’’, crash barriers are designed with only cars and heavy vehicles in mind and may pose a danger for singletrack vehicles, transmission of traction force: two-track vehicles - at least on two wheels (sometimes on four), single-track vehicles – on only one, and finally kW/kg ratio. Consequently, riding a motorized two-wheeler is more dangerous than driving other motor vehicle.

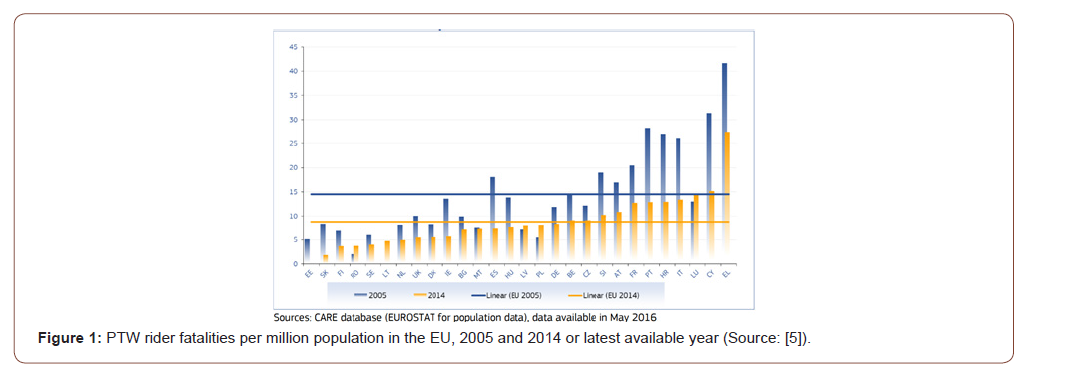

PTW riders in the European Union are one of the most vulnerable groups of road users [1]. They are quite often involved in road traffic accidents and, unfortunately, in many cases can be seriously injured or even killed. Some studies of PTW accidents have reported that approximately 96% of riders of PTWs involved in traffic accidents are at great risk of suffering certain injuries [2]. Moreover, other studies show that even in 50% of such accidents, serious injuries or even death of the rider occurred [3] (Figure 1).

In the EU the number of fatalities per 100,000 registered motorcycles is twice as high for motorcycle riders as the number of fatalities for car passengers per 100,000 registered cars [4]. In 2014 alone, approximately 26,000 people were killed in road accidents across the EU and PTWs accounted for 17% of those fatalities (compared to 16% in 2005). In 2014, at least 3,841 PTWs riders (drivers and passengers) of motorcycles were killed in the EU in road accidents [4] Figur 1. shows that between 2005 and 2014 the road traffic fatality rate of PTWs decreased in most EU countries. Significant decreases were recorded in Italy, Portugal and Cyprus, whereas the fatality rate increased in Romania and Poland [5].

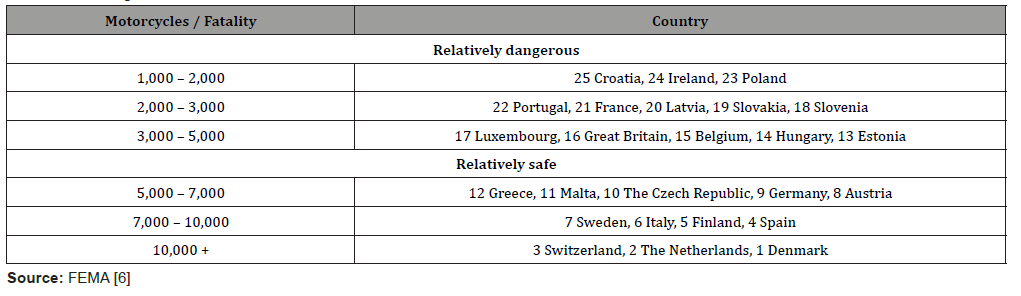

A first indication of traffic safety is obtained by relating the number of motorcycles to the number of fatal motorcycle accidents in a country (Table 1) [6]. Official European Commission statistics report about 4,500 fatal motorcycle accidents for 2012. The danger rank of each country is based on calculating the number of registered motorcycles per fatal accident. The more motorcycles per fatal accident, the safer the country is; the fewer motorcycles per fatal accident, the more dangerous the country is. Countries can then be classified into two categories as relatively safe or relatively dangerous compared to the European average. The number listed for each country is its danger rank: 1 is the safest country, 25 is the most dangerous country. The European average is 5,000 motorcycles per fatality. For countries did not categorize the required data is not available.

Table 1:The danger rank of countries.

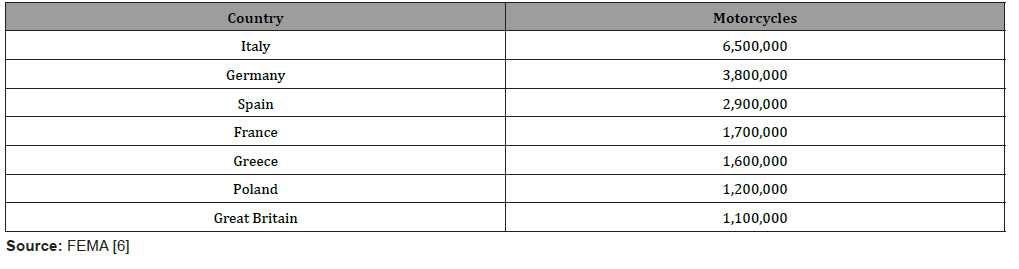

There are an estimated 23,000,000 motorcycles in 31 European countries according to 2013 Figures from the European Association of Motorcycle Manufacturers (ACEM) [6]. Seven countries have more than one million motorcycles, with Italy holding the absolute top position (Table 2). In the last few years the total number of traffic accidents in Slovenia has decreased whilst the number of accidents involving PTWs has increased. In 2017, 104 people died in all road accidents in Slovenia, the lowest number recorded in the last 60 years. In contrast, during the same year there was a noticeable increase in the number of PTW rider fatalities. By the end of 2017, there were 29 fatalities among PTW riders, which, in comparison to the previous year (2016, 24 fatalities) represents an increase of 21%. In 2017 the proportion of PTW fatalities was 24% out of all road accident fatalities, which is the worst Figure since records began. In addition, the proportion of PTW riders that were seriously injured or killed in comparison to the overall number that were seriously injured or killed in all traffic accidents was significantly higher than the proportion of PTW riders in the traffic structure.

Table 2:Estimated number of motorcycles.

Past Awareness Campaigns and Implemented Measures for PTWs in Slovenia

For several years Slovenia has been implementing various campaigns and introducing various measures in order to become a motorcycle-friendly country. Until now, several preventive awareness campaigns and additional educational campaigns have been carried out, whilst various measures have also been implemented that aim to lessen the consequences of road accidents involving motorcyclists.

In the past Slovenia tried to improve the low-level of traffic safety of PTWs in various ways; the following measures were generally used:

• preventive campaigns and additional education,

• additional non-traffic signs and road markings,

• improved road/roadside safety conditions.

Preventive awareness campaigns and additional education are considered a ‘long-term investment’, as the positive consequences are only visible after an extended period. This measure includes the production and distribution of promotional flyers, brochures and posters (Figures 2&3). containing precautionary contents in order to promote better traffic safety.

Implementation of additional traffic/non-traffic signs and road markings is a less widespread approach for improving PTW traffic safety. The following measures have generally been used in Slovenia:

• preventive non-traffic signs that are not a part of the Slovenian regulation (Figure 4).

• additional road markings that are not a part of the Slovenian regulation.

• Improved road/roadside safety conditions can be accomplished through the implementation of physical measures. The aim of such physical elements is to achieve a higher level of safety on the road and particularly in areas directly next to roads (roadside). These measures are also called infrastructure safety improvements:

• motorcycle-friendly roadside barriers (Figure 5a),

• motorcycle collision shock absorbers (mounted on guardrails posts),

• passive-safe posts for marking the course of bends and connections (reflective flexible bollards or “balisette’’ bollards instead of rigid road signage) (Figure 5b).

The best results were obtained in Slovenia through the use of additional non-traffic signs and motorcycle-friendly roadside barriers.

However, all these measures mentioned above are of a reactive nature and were only installed after it was found that some locations are dangerous for PTW riders. Logically, there was a demand to do something proactive in terms of road design, equipping and maintaining phases before traffic accidents involving PTW riders occurred. The condition for this is an understanding of the motorcyclists’ behavior.

Gaze Behavior of Motorcyclists and Passenger Car Drivers in Urban Areas – A Visual Comparison

Eye-tracking technology

In the recent past, research in the field of driver distraction connected to traffic situations and roadside was often performed using simulations, which do not necessary reflect the real environment, consequently the results were not always reliable.

The use of mobile eye-tracking solutions for the analysis of different types of road users is steadily increasing. In the beginning, the researchers mainly used mobile eye-trackers in laboratories and carried out experiments indoors. However, these experiments do not reflect the realistic behavior and situation of road users in the real traffic environment. Therefore, researchers are now conducting a growing number of studies in real environments [7].

While researchers have analyzed the visual perception of pedestrians and car drivers in many eye-tracking studies [8], there are only few studies that have been conducted with powered twowheelers. Although important research has been conducted in the past on the correlation between the behavioral perceptions of motorcyclists and their actual behavior [8], changes in the behavior of drivers when driving a motorcycle or car [9], the way motorcyclists recognize objects at the roadside (e.g. advertising) [10] and how motorcyclists react to safe and unsafe roadsides [1], this area has not yet been sufficiently investigated.

The issue is even more complex because the Haddon matrix is slightly different for a motorcyclist [11] than for a car driver. In contrast, road equipment (e.g. locations of traffic signs, types of safety barriers, road markings, etc.) is generally adapted to cars, buses and trucks [12].

Eye-tracking technology enables analysis of whether different types of road users are potentially aware of each other, of traffic lights, traffic signs, road markings, curve curvature or dangerous static or dynamics obstacles on the roadway or at the roadside. The eye-tracking technology offers the possibility to evaluate the focus of the drivers and the fixation of their gaze with minimal distracting equipment. It also enables research in real environments and under real traffic flow conditions in order to obtain information that is as realistic as possible.

In the presented research we apply a visual analytic-based method to analyses the gaze behavior of motorcyclists and car drivers. This is done in real world eye-tracking settings in different traffic situations in urban areas to find out their differences.

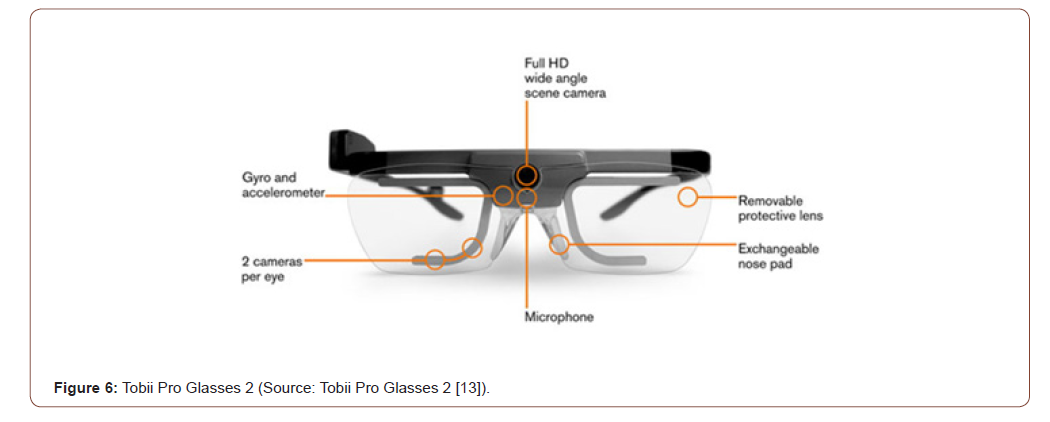

We conducted the studies with a Tobii Pro Glasses 2 (Figure 6). Tobii Pro Glasses 2 gives researchers deep and objective insights into human behavior by showing exactly what a person is looking at in real time while moving freely in any real-world environment. Using the Tobii Pro Glasses 2 makes it easy to understand how people interact with their environment, what attracts their attention, determines their behavior and influences decision-making. Tobii Pro Glasses 2 enables advanced analysis using tools such as heat maps, gaze replays, areas of interest (AOI), output metrics such as time to first fixation & time spent [13].

Method

We conducted the study in an urban area of a city in Slovenia, where the speed limits differ. The definition of the route for the research was based on the investigation of possibilities to include different relevant traffic situations and road infrastructures, consequently also different roadsides. In the studies, the participants had to follow a predefined route, which included driving along the road (free section), driving at intersections (traffic lighted and priority-controlled intersections), at roundabouts (standard singlelane, turbo and assembled mini roundabouts) and driving through the tunnel.

Some restrictions were applied in the selection of participants involved in the studies. We have selected riders and drivers without heavy make-up, without prescription glasses and without drooping eyelids. We have also applied some restrictions in the choice of motorcycle helmets. Although there are six main types of motorcycle helmets, we have used only modular (“flip-up’’), half and full open face helmets in the studies. During the tests, motorcyclists only rode with a visor for eye protection and without a secondary inner visor for additional protection from sunlight.

We conducted the studies with a total of 20 participants (10 passenger car drivers and 10 motorcyclists).

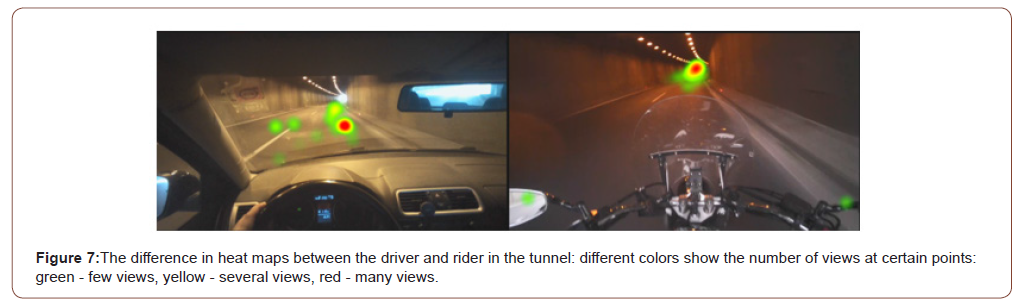

For the analysis of the eye-tracking data a Tobii ProLab software was used [14]. ProLab is the eye-tracking software designed to perform experimental investigations with Tobii Pro hardware that displays the real-time fixations and focus of the driver on a background video of what the driver saw. In addition, it also enables a single image (frame-by-frame analysis) of the videos and an automated assignment of the real-world mapping (see Figure 7).

Research

Due to the complexity of the traffic environment (free section, intersections (traffic lighted and priority controlled intersections), roundabouts (standard single-lane, turbo and assembled mini roundabouts) and a tunnel) an abstract reference image of the scene was used to define areas of interests (AOIs) and map fixations of them was used.

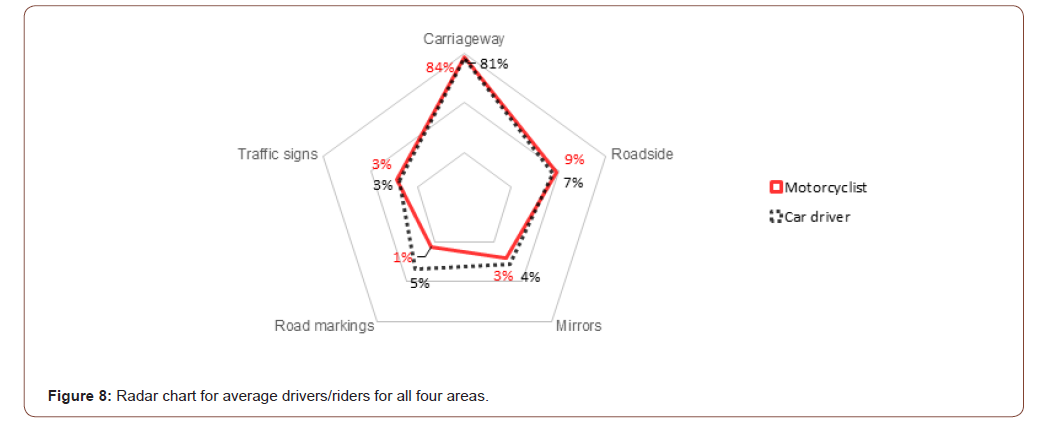

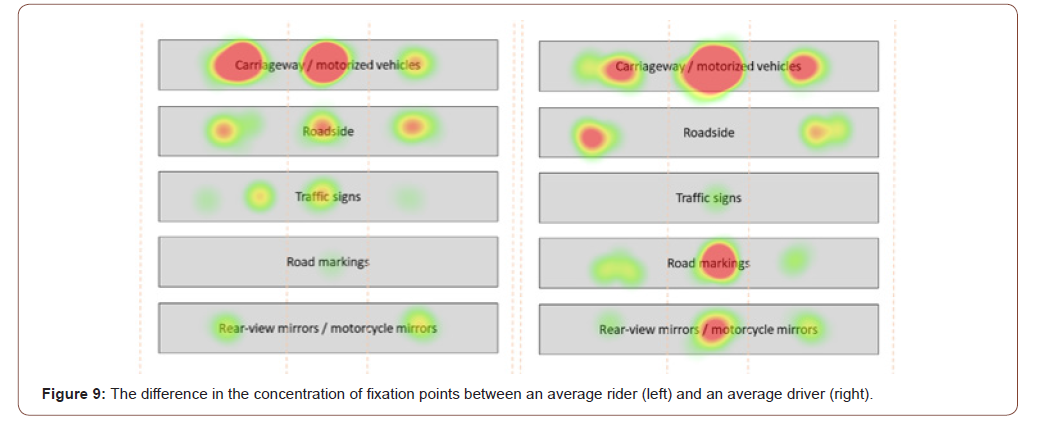

We focused on the carriageway (and motorized vehicles in both lanes), roadside, traffic signs, road markings and rear-view mirrors/motorbike mirrors (Figure 8).

After mapping fixations to AOIs, the next step was the annotation of interesting situations and an explorative visual analysis.

We performed a separate analysis for each driver/rider, and a separate analysis for each of the four areas. We first looked for which objects driver/rider concentrate on most. Then we searched for what common sequences do riders and drivers perform and how their behavior does differ. In the end, we summarized all results separately for drivers and riders and calculated the average values (Figure 9).

Findings

Data for each participant were statistically processed. Subsequently, the results were combined, separately for drivers and bikers. The results of the analysis are as follows:

In general, the gaze behavior of riders and drivers differ and depends on the traffic situation. Although in general we can say that there is almost no difference between riders and drivers when focusing on carriageway and roadside, there is a significant difference when focusing on traffic signs and mirrors, and the most important difference is the focus on road markings. The difference in focusing depends on the traffic situation (speed limit, free section (with or without tunnel) or intersections (traffic lighted, prioritycontrolled or roundabout)).

The predominant focusing of the riders on the carriageway is understandable. Causes or dangers for increased riders attention on the carriageway include interaction between riders and other motorized road users, flatness, skid resistance, potholes, cracks, dust and sand, longitudinal grooves, debris and dropped loads, spillage on the road surface, aquaplaning/hydroplaning, unexpected changes in road condition, road surface, repairs etc.

Causes or dangers for increased rider attention at the roadside include the presence of roadside hazards without safety barriers, poor shoulder maintenance, dangerous longitudinal drains, the impact of riders against a solid object, collisions with unprotected safety barriers, etc.

Focusing on traffic signs is somewhat less important for a rider than for a driver, as the rider “watches a road”, especially on bends. Since the rider is most often focusing on the carriageway and not on traffic signs, legitimate idea arises that the most important traffic signs for riders appear on the carriageway (pictograms).

The mirrors are more important for riders than for drivers because of their vulnerability.

We can conclude from this that the gaze behavior of the rider and the driver is different. How big the difference is depending on the traffic situation.

Conclusion

The vulnerability of PTWs has been established with the large number of road accidents and poor safety statistics in many European and world countries. PTW riders in the European Union are one of the most vulnerable groups of road users. They are quite often involved in road accidents and, unfortunately, in many cases can be seriously injured or even killed.

Preventive awareness campaigns, additional education and training, additional non-traffic signs and road markings, physical measures to mitigate the effects of road accidents involving motorcyclists, are only a part of the efforts to provide motorcyclists safe participation in traffic.

Much can also be done by safer road design, and safer equipping and maintaining, taking into account also motorcyclists. The condition for this is an understanding of the motorcyclists’ behavior. Because of their vulnerability, riders have to concentrate on the traffic rather than on the carriageway and roadside, but infrastructure deficits are often the primary or at least a contributing factor in motorcycle accidents. Especially because road design, equipment and maintenance are mostly determined by the needs of other motorized vehicles, with road standards and guidelines generally taking little account of the specific needs of motorcyclists.

In order to better understand the behavior of a motorcyclist, we made a comparison of his behavior with the behavior of a personal car driver. We limited on visual comparison of gaze behavior.

We have found that the gaze behavior of motorcyclists and personal car drivers differs and depends on the traffic situation. In general, we can say that there is almost no difference in focusing on the carriageway and roadside, but there is a significant difference in focusing on traffic signs and mirrors, and the most significant difference is in focusing on road marking. How big the difference is depending on the traffic situation.

Because of this difference it is clear that there is a need to search new approaches to road design, equipment and road maintenance from motorcyclists’ traffic safety point of view.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to the Slovenian Ministry of Infrastructure, Slovenian Infrastructure Agency who commissioned all abovementioned studies.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Šraml M, Tollazzi T, Renčelj M (2012) Traffic safety analysis of powered two-wheelers (PTWs) in Slovenia. Accident Analysis & Prevention 49: 36-43.

- Hurt HH, Ouellet JV, Thom DR (1981) Motorcycle Accident Cause Factors and Identification of Countermeasures. Volume 1: Technical report. Traffic Safety Centre, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 435 p.

- Diamantopoulou K, Brumen I, Dyte D, Cameron M (1995) Analysis of Trends in Motorcycle Crashes in Victoria. Report No 84. Monash University Accident Research Centre. 126 p.

- European Commission (2015) Power Two Wheelers, European Commission, Directorate General for Transport.

- European Commission (2016) Traffic Safety Basic Facts on Motorcycles & Mopeds, European Commission, Directorate General for Transport.

- FEMA (2016) Motorcycle Safety and Accidents in Europe.

- Trefsger M, Blascheck T, Raschke M, Hausmann S, Schlegel T (2018) A Visual Comparison of Gaze Behavior from Pedestrians and Cyclists. ACM Symposium ETRA '18, Poland.

- Topolšek D, Dragan D (2018) Relationships between the motorcyclists' behavioral perception and their actual behavior. Transport 33(1): 151-164.

- Topolšek D, Dragan D (2015) Behavioural comparison of drivers when driving a motorcycle or a car: a structural equation modelling study. Promet 27(6): 457-466.

- Topolšek D, Areh I, Cvahte Ojsteršek T (2016) Examination of driver detection of roadside traffic signs and advertisements using eye tracking. Transportation research. Part F: Traffic psychology and behaviour 43: 212-224.

- Delhaye A, Marot L (2015) Infrastructure, Deliverable 3 of the EC/MOVE/C4 project RIDERSCAN.

- Tollazzi T (2018) Measures for improving traffic saffety of motorcyclists. Proceedings, 14th International Symposium Road Accidents Prevention. Novi Sad, Faculty of Technical Sciences, pp. 309-316.

- (2019) Tobii Pro Glasses 2 - Discontinued.

- (2019) Tobii Pro Lab.

-

Tomaž Tollazzi, Matej Moharić. Key Components of A Motorcyclist Safety – Case Study Slovenia. Glob J Eng Sci. 5(2): 2020. GJES. MS.ID.000622.

-

Powered two-wheelers, Safety, Infrastructure, Measures, Eye-tracking

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.