Mini Review

Mini Review

A Participatory Model for the Regeneration of Australian Cities: The Case of Geelong

Hisham Elkadi*

Dean of Architecture and the Built Environment, University of Salford-Manchester, UK

Hisham Elkadi, Dean of Architecture and the Built Environment, University of Salford-Manchester, UK.

Received Date: February 18, 2020; Published Date: February 24, 2020

Abstract

Urban regeneration projects have become a key focus of attention in cities globally. The case study of Geelong City, Australia, illustrates the challenges of maintaining the viability and relevance of the city while shifting from its historical industrial character. The Vision II urban regeneration project aimed to revive Geelong city center. The project adopted the process of crowd sourcing where both individual and organization sectors collaborated aiming to achieve a better quality of life. The project consisted of several crucial elements including partnership working, project governance, participatory workshops, scenario creation, community engagement and a transparent flow of this information to the community at large. This paper aims to expose the process used for this project as a valuable contribution to future urban regeneration development activity. The process involved different types of citizen’s involvement aiming to create a powerful partnership between the different stakeholders. The conclusion identifies the main strengths in the process that can be later implemented in other urban regeneration projects.

Keywords: Crowdsourcing; Participatory governance; Urban regeneration; Waterfront regeneration; City development; Vision II project; Geelong city

Planning for Urban Regeneration

The changing role of the citizen

Roberts et al. [1] defined urban regeneration as “a comprehensive and integrated vision and action which leads to the resolution of urban problems and which seeks to bring about a lasting improvement in the economic, physical, social and environmental condition of an area”. This definition suggests that urban regeneration is a strong means of achieving future sustainable cities. Accordingly, the concept has been a key focus for research, planning processes and public policies [2,3].

Urban regeneration projects implicate different stakeholders including individuals and organizations [1]. They require continuous efforts from their involved stakeholders. However, they do not usually meet their expected outcomes. These shortfalls usually center on not fulfilling the needs of the end users who should be part of the regeneration process. Even for projects using the participatory approach, the involvement of multiple stakeholders is mostly limited to reviewing the different scenarios presented by the experts and choosing a preferred action [4]. This involvement is mainly employed to gain local support. Raco [5] added that these projects focus on the needs of developers without considering the local community, which ultimately leads to unsustainable outcomes [6]. In his statistical study, Jones [7] emphasized the gap between urban regeneration projects’ intentions and outcomes due to urban deprivation of the local community. He added that these projects failed to improve the ‘local economies or the lives of local residents in the way that had been hoped’. As Schuurman et al. [8] stated, “When the ideas and opinions differ significantly from the already established policies and goals of the organization, a gap is revealed between the City and its citizens”. An example of this was the African governmental urban regeneration project, which aimed to develop telecentres in regions that failed, as the majority of the population were unable to access telecommunication [9]. These regeneration efforts reach unexpected outcomes, as they do not consider addressing the local community’s needs as their key focus in regeneration [6]. In England, physical regeneration in ex-industrial cities has historically been ineffective resulting in a strong shift towards community-led regeneration [10].

Despite increased focus on community-led regeneration approaches, few examples demonstrated instances where planners had genuinely engaged their local communities in formal regeneration decision-making processes [11]. The majority of projects limited their contribution into reviewing the alternatives designed by the planners. As Ball [12] explained that, these methods create ‘conditions that limit co-operation between divergent partners. To achieve more sustainable outcomes, the public, private, and community sectors should collaborate on more equal terms participation, with the aim being a better quality of life for all citizens. Gaye wt al. [13] added that this “newly empowered local community, through democratic decision-making and problem solving, matures into a body capable of interacting collectively with the local authority and even with agencies from higher levels of government”. De Beer [14] differentiated between “involvement” and “empowerment” as two different development approaches to community participation projects. He added that the “involvement” trait is a top down approach in which outsiders identify the need and planning answers, which lead to a failure as it disregards the ownership of development. Conversely, the “empowerment” trait enables to decentralize ownership and decision making to the public, which creates self-awareness as well as a transformation to the community [15].

Deng et al. [16] argued that the bottom up approach of community participation has been promoted by the expansion of internet-based communication platforms offered by new forms of media. They reflected that the global interconnectedness of people and places [17] and the development of network power [18] have to both be addressed in the community participation process. Innes et al. [19] stated that the ideal model of participation is realized when different stakeholders discuss their shared problem in person. However, engaging the community is challenging particularly when dealing with the conceptualization of places and detailing urban forms [20]. To reduce this gap between professionals and the community, planners are required to act as mediators to alleviate concerns surrounding the community’s comprehension for considered spatial concepts. This task is promoted with the extensive usage of social network websites including Facebook and Twitter among other public and semi-public forums where users share information. Deng et al. [16] added that these websites can “effectively built up social capital that can be regarded as a trust fund held by social networks that enables individuals to participate in achieving a common goal and facilitate collective actions...can also facilitate a more transparent and accountable public decision making process, due to the availability of more information”. Accordingly, using these internet-based communication resources can lead to an extensive interaction between the different stakeholders involved in the urban process including the public authorities and professionals as well as the community.

The crowdsourcing method originally used as a business web-based model can also be employed to engage communities in the urban process and help public authorities to receive their input [21]. Although this method can involve the majority of the population and organizations, some civilians can be marginalized due to being unfamiliar with internet-based tools. As the success of collaborative planning relies on the contribution of different stakeholders, it is essential to find additional ways of communication to engage the different categories of users. Therefore, given the need to understand how participatory approaches can operate to provide more sustainable and collaborative community-oriented approaches to planning, this paper explores these concepts further by demonstrating how they were implemented in the urban development in Geelong, Australia: The Vision II project.

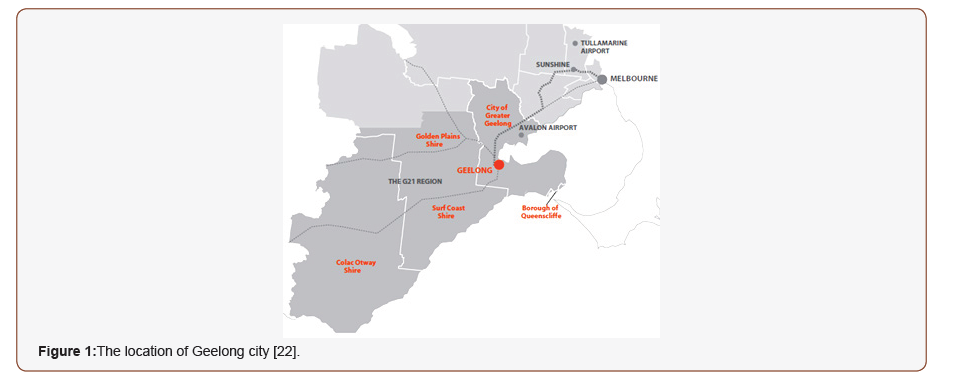

Greater Geelong is the second largest city in the state of Victoria. The coastal city is situated around 75 km South West of Melbourne City (Figure 1). Central Geelong is located on a northfacing slope flanked by Corio Bay from the north and the Barwon River from the south. The history of the city can be traced back to 1803 as the main regional hub and port for Western Victoria. Eventually, Geelong became a key trade center as well as an industrial hub. A variety of industries dominated, including wool and paper manufacturing and later Ford automobile production. Currently, the city has transitioned from its industrial character to a high technology-based region with vibrant education and health facilities. In addition, it became a hub for various research initiatives including epidemiology, gene technology, clinical trials, advanced materials, nanotechnology and fiber technology that grew to be strong driving economic forces. The Centre Business District of Geelong (CBD) (Figure 2) combines a variety of shopping, investment opportunities, health and education facilities, as well as cultural assets including the Geelong Performing Arts Centre, gallery, museums and the botanic gardens [22].

Background: Vision I Urban Regeneration Project

Preceding Vision II, ‘Vision I’ project involved redeveloping Geelong’s waterfront, as one area of focus for regional growth, under the leadership of both the Victorian State Government and the City of Greater Geelong. The project commenced in the 1990s and involved converting the city’s industrial and maritime precincts to a recreational and touristic site characterized by its vitality, which was positively reflected on the economy of the city. To improve the public realm, keys young in collaboration with urban initiatives and the city of Greater Geelong created a master plan document: the ‘Waterfront Geelong Design and Development Code 1996’ [23]. These improvements included the waterfront that was remodeled into a high-quality public realm with investment in public art and infrastructure including restaurants, swimming area, a new skatepark and other waterfront attractions. The development also involved private investments such as Deakin Waterfront Campus that occupied the original 1893 wool stores as well as a number of residential developments.

Vision II Urban Regeneration Project

Following the public realm achievement of Vision 1, and in conjunction with the G21 Regional Growth Plan under development as well as the growing quality of the city, it was vital for the city of Geelong to build on progress with a further urban development project. Vision II inaugurated in 2011 aiming to reach a shared futuristic vision for the Centre Business District (CBD) of Geelong city; as well as identify areas, strategies and opportunities to provide a vision, momentum and investment for the growth of central Geelong. The vision was directed to neutralize the industrial character of Geelong and intensifying its viability and significance. the main challenges facing the project involved the conversion to a knowledge-based global economy focusing mostly on the education and health sectors – education led regeneration, creating a sustainable future with an ecologically sensitive urban environment as well as building on the sense of community and the distinctiveness of place.

The project’s outcomes were to produce scenarios for change between 2011 and 2031 to support Geelong in becoming sustainable and successful, which were developed by leading industry professionals, state and local government in addition to the local community. To accomplish this, it was crucial to initially develop a powerful Partnership with effective leadership, which was creative, imaginative and risk-taking. The establishment of this framework addressed economic, social, environmental and cultural issues, which are central to providing a sustainable Geelong city of 2031 [22].

The Stakeholder Partnership

Vision II was established in 2011 with a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed by the local council of Greater Geelong (COGG), the State Government- Department of Planning and Citation: Hisham E. A Participatory Model for the Regeneration of Australian Cities: The Case of Geelong. Glob J Eng Sci. 4(4): 2020. GJES. MS.ID.000595. DOI: 10.33552/GJES.2020.04.000595. Page 4 of 8 Community Development (DPCD), Deakin University (DU) and the Committee for Geelong (CFG) who represented the business group. The project was governed by this unconventional collaborative partnership to develop a vision for future development of the Central Business District of Geelong city (Figure 2). The aim was to build a close working relationship to develop a vision of bold ideas for future development. Therefore, it was crucial to work in a creative environment to generate ideas, images and plans that could be explored and challenged through stimulating non-binding conversations that might be held outside of formal roles, with the flexibility to debate ideas without holding to a position. Being funded by the state government (DPCD), the project was expected to follow the usual structure of urban regeneration projects of the parliamentary procedures. With such imprecise aims, the challenge laid in obtaining funding: unless it could be realized that funds were a prerequisite for a crowd-sourcing initiative. Additionally, some significant challenges associated with ecological principles and population dynamics were addressed.

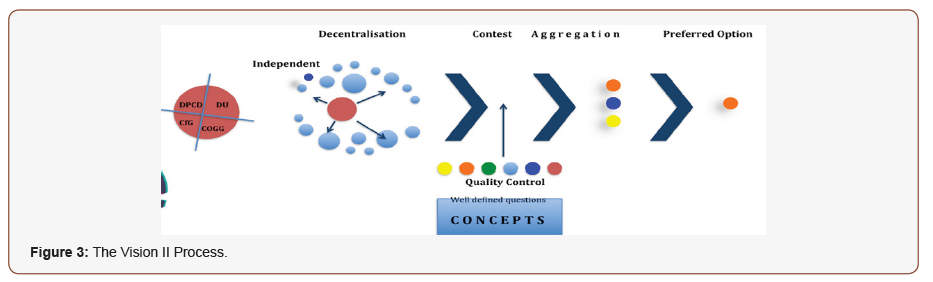

Unifying partnership perceptions was a core goal of this crowdsourcing performance. This helped to solidify the partnership, create the catalyst for the crowd and prevent outsiders to manipulate the process. As shown in Figure 3, starting the project with the partnership as one unity acted as the catalyst around which other layers were built up. These layers helped in obtaining information from different parties who could work together as a hub. The process then reached the wider audience from moving out to the contest of the concept towards aggregation ending with the choice of the preferred option.

Vision II Process (The Development Strategy)

Following the initial decision to collaborate, Vision II aimed to develop a process and scenarios for change. To reach full potential, a shared vision and communication between stakeholders was required. The project partners ensured a transparent process to which the public were engaged and aware of its development.

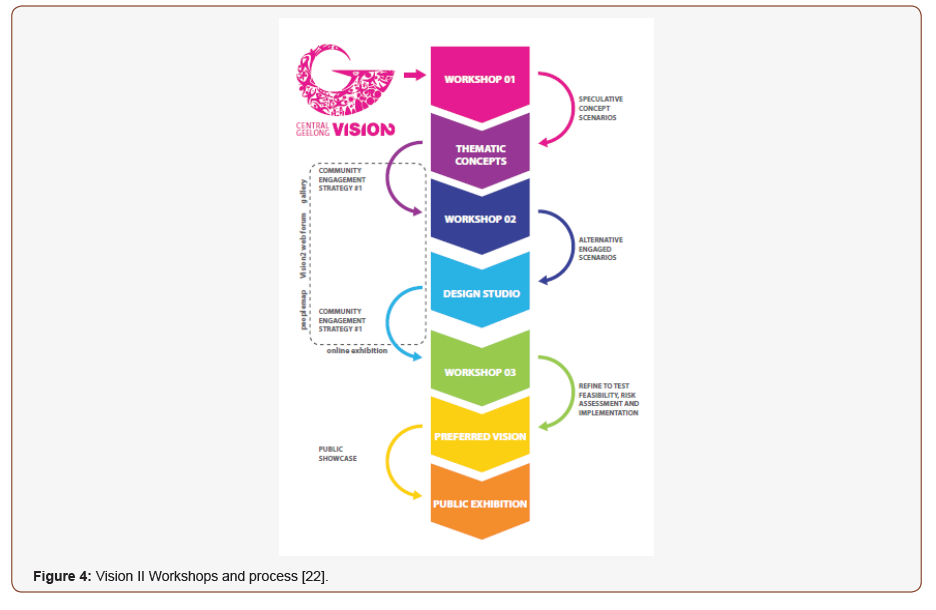

The project’s timeframe included a series of workshops (Figure 4) hosted by Deakin University encompassing international, national and local professionals from a wide variety of disciplines. These workshops operated in parallel with a series of community engagement events. The whole process was also supported and validated by international experts, who also helped to frame the appropriate questions for different stages of the project.

Target Population

As the project was concerned with the idea of crowd sourcing and community participation, it was crucial to recognize the population growth and demographic changes in the city. According to the 2011 Census, Geelong accommodated 250651 people where 30% are born overseas [24]. Having the largest and fastest growth in regional Victoria of 13% between June 2001 and June 2011, the city is expecting high numbers of migrations especially intrastate migration. A percentage of 26% of the population are expected to be over the age of 65 in 2031 with a high average of obesity. As the project then deals with aging population, intrastate migration as well as a multicultural society, it was important to attain the type of communication to reach this challenging crowd sourcing.

The Workshops

To achieve dynamic and innovative thinking in the scenarios, the first stage of the project involved a series of designed-based workshops hosted by Deakin University throughout 2012. Each workshop involved different international, national, and local participants and professionals, drawing on expertise and excellence from a wide variety of design disciplines to support the project.

Workshop 1

The first workshop occurred in May 2012, aiming to develop the first set of key themes and scenarios that were taken further into the Vision II process. A number of well-known professionals from architecture, urban design, planning, and landscape architecture; in conjunction with Deakin design students, volunteered their time and accepted to contribute in this workshop session. Being from different local, national and international companies, they assembled the experience and understanding of large-scale regeneration projects with the knowledge of the local area. Participants were grouped into six teams with a balanced representation from different professional backgrounds. Using their observations of the area, along with professional expertise, each team was asked to identify the current situation, and try to picture the future for central business district of Geelong.

The essence of the workshop was to examine what can happen to central Geelong, in both physical and non-physical senses in order to be a great regional city in Victoria over the next 20 years and beyond. Two creative sessions shaped the workshop: one was concerned with ideas, brainstorming and initial discussion while the other involved responses that were articulated through visual mediums and verbal communication into design format. To facilitate the discussion and generate ideas for the future of Geelong, a series of enquiries were proposed including into the main opportunities and aspirations of the city, how to facilitate them as well as their impact on people’s experience of the city. The workshop revealed discussions and ideas surrounding the future vision for central Geelong; however, as they responded to the context with no limitations to aspirations. Accordingly, the essence of the outcomes was carried through to thematic concepts and scenarios for central Geelong.

Workshops 2 and 3

The same process employed in the first workshop was repeated in two successive ones. However, in the second workshop, a different group of leading professionals were invited to start their discussions using the scenarios taken from the first workshop. The workshop aimed to merge the different thematic concepts into scenarios that were later presented to the agencies in workshop 3 in which the final preferred option was selected.

Community Engagement

In addition to the professional contribution, the success of Vision II rests with the community as the futuristic vision was intended to be multi-faceted to reflect the interests of the different stakeholders. The community of Geelong were accordingly encouraged to be involved in the process from its start. Community consultation was achieved through the ‘People map’ group who recorded semi-structured interviews in a range of public places including Westfield shopping center, Pakington Street and Berkley Park Market in Geelong. In addition to the interviews and workshops, the team were available to be contacted directly and there were active Vision II web forums and social media opportunities through Facebook and Twitter pages for joining the discussion. This public engagement helped to identify the positive and negative aspects distinguished in the city as well as encourage people to feel as though they were among the experts involved in the project. Other events were hosted to ensure the transparency of the process including ‘Vision II gallery’ that was open to public to monitor the development of the project.

The key issues of the public concerns that were addressed in the vision included:

• The poor pedestrian experience in the city center that resulted from the lack of hierarchy between streets,

• The weak sense of arrival resulted from the absence of a clear entrance or reference to the city center,

• The unattractiveness of the shopping and eating areas in the city center when compared to other surrounding town centers,

• The high vacancy rates,

• The poor quality and diversity of commercial rental offers,

• The need of an ecological urban environment that supports a healthy city and population and ensures a sustainable living.

• The presence of internalized public domains, which are only vibrant during the opening hours.

Vision II Studio Group

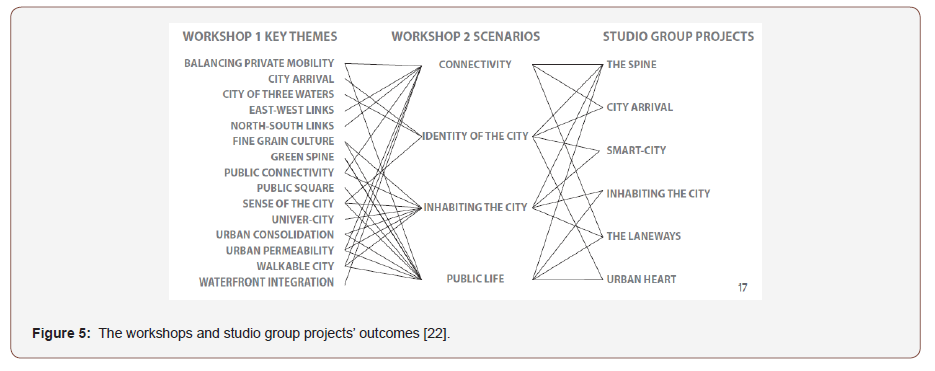

Following the second workshop, the Vision II Studio group was formed to display the output of the two first workshops as well as facilitate community engagement. The wide array of outputs produced was managed in the studio to produce visual material reported to the implementation strategy. These materials ensure a level of understanding between the partnership and wider interest groups with regard to the final vision. The key themes and scenarios are detailed in Figure 5.

International Experts

After merging the output of the professionals and crowd engagement, Vision II drew together international experts to validate the process and outcomes of the project as well as to fortify the position of the partnership. The international support involved Marta Schwartz, Jan Gehl and Richard Sommers. Marta is a professor at Harvard Graduate School of Design and one of the most well-known landscape architects, with involvement in public places projects in different cities including Dublin, Washington, New York and Dubai. Jan, a recognized architect and urban design consultant based in Copenhagen, with an interest in improving the quality of urban life, and involvement in different public realm projects in London, New York, Australia and New Zealand. Richard, the Dean of Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design, University of Toronto. This unusual level of engagement involving international support validating the crowd’s ideas was extremely efficient as it added value by harnessing global thinking for a local problem. This step showed the difference between the usual process of using experts to finalize the plan then discuss it with the crowd and letting the crowd originate the real ideas then validating them.

The Final Stage

The preferred scenario targeted establishing a strong sense of place and maintaining the heritage of the city, in addition to restoring some of the original features of Geelong. Education, healthcare and infrastructure were also key to the regeneration vision of Geelong. Additionally, imaging and branding of the city were considered. Geelong is imagined to be identified as the ‘beautiful green city by the water’ through a proposed ecological green spine which provides a vital route through the city. This spine was one of the challenging proposals to be implemented through the normal regeneration process. The spine, which embraced both sustainability and ecology was first considered as impossible by some organizations such as VicRoad, however, at the end of the project it was favorably received by all the stakeholders.

The partnership aimed to avoid the ownership of ideas by any one sector throughout the process and support the transparency and democracy of the project. Accordingly, instead of using a professional consultant to manage the nature and format of documentation of the project, they depended on volunteers.

The Working Groups

Managing the process of Vision II involved both creativity and compliance. To produce creative thinking while fulfilling necessary parliamentary procedures and reporting, three different groups worked in parallel. The workshop and design group were responsible for running workshops, which generated scenarios that were later displayed in the gallery and led to the final development of the future vision for Geelong. The data group managed the data including the current layout and development of the central business district of Geelong that were fed into the workshop group. The same group were also concerned with producing governmental reports and the background report used by all the groups. Finally, the community engagement group was actively connected to the community through the social media, website, direct community correspondence and Gallery in addition to appointing ‘Peoplemap’ to conduct a series of semi structured interviews in public places.

Conclusion

Vision II aimed to develop a sustainable future vision for Geelong that facilitates a thriving economy and a vibrant central business district with various amenities to its population. The project included partnership working, project governance, workshops, scenario creation, community input and a transparent flow of its development. The vision was multi-faceted to reflect the interests of different stakeholders and sustain a framework that supports the ecological and economic improvements. The proposed crowd-sourcing approach was preceded by a strong partnership between the City of Greater Geelong, the Department of Planning and Community Development, Deakin University and the Committee for Geelong who worked together as one catalyst for the crowd. Since its inception, Vision II was confronted with the question of democracy and representation in terms of convincing the stakeholders to be only part of the picture rather than the experts. However, through the different stages, the partners were keen to avoid the idea of ownership of any sector, which can disrupt the process of crowd sourcing.

A series of public workshops and semi structured street interviews took place to ensure that communities are engaged to feel a sense of ownership from an early stage in the project. The main idea was to let the crowd feel the experts instead of just consulting them. This process generated creative thoughts that were later validated through international experts including Martha Schwartz, Jan Gehl and Richard Summer. This level of international engagement and support endorsed the process and reassured stakeholders’ equal partnership. Later, a public gallery was launched for the public to visit and see the development of the project. Using this process allowed the crowd to be the actual experts in the project and their creative ideas were later endorsed by international experts. As governmental procedures can confine a certain line of management, there was a specific working data group that were liaising with the two other groups to deal with the governmental reporting.

Ensuring the engagement of the crowd and the transparency of the process were key success factors for the project. However, the current bureaucracy of the states’ system and the crowd autocracy impose a planning process that is preoccupied with data gathering. Dismantling rational evidence-based systems of data in favor of generating local intelligence where the community is engaged was the most crucial task that led to a creative approach to planning stages.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Roberts P, Sykes H (2000) Urban Regeneration: A Handbook. London.

- Colantonio A, Dixon T (2011) Urban regeneration and social sustainability: Best practice from European cities: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 334.

- Tallon A (2010) Urban regeneration and renewal: Routledge.

- Lombardi PL (1999) Understanding sustainability in the built environment: a framework for evaluation in urban planning and design. University of Salford.

- Raco M (2007) The planning, design and governance of sustainable communities in the UK. Securing an Urban Renaissance: Crime, Community and British Urban Policy, The Policy Press: Bristol, pp. 39-56.

- Nisha B, Nelson M (2012) Making a case for evidence-informed decision making for participatory urban design. Urban Design International 17(4): 336-348.

- Jones A (2010) New approach is needed to revive our cities.

- Schuurman F, Van Naerssen T (2012) Urban social movements in the Third World: Routledge.

- Jung TH, Lee J, Yap MH, Ineson EM (2015) The role of stakeholder collaboration in culture-led urban regeneration: A case study of the Gwangju project, Korea. Cities 44: 29-39.

- Webber C, Larkin K, Tochtermann L, Varley-Winter O, Wilcox Z (2010) Grand Designs? A new approach to the built environment in England’s cities. Centre for Cities, London.

- Hall S, Hickman P (2011) Resident participation in housing regeneration in France. Housing Studies 26(6): 827-843.

- Ball M (2004) Co‐operation with the community in property‐led urban regeneration. Journal of Property Research 21(2): 119-142.

- Gaye M, Diallo F (1997) Community participation in the management of the urban environment in Rufisque (Senegal). Environment and Urbanization 9(1): 9-30.

- De Beer H (1996) Reconstruction and development as people-centred development: challenges facing development administration. Africanus 26(1): 65-80.

- Lyons M, Smuts C, Stephens A (2001) Participation, empowerment and sustainability:(How) do the links work? Urban Studies 38(8): 1233-1251.

- Deng Z, Lin Y, Zhao M, Wang S (2015) Collaborative planning in the new media age: The Dafo Temple controversy, China. Cities 45: 41-50.

- Healey P (1997) Collaborative planning: Shaping places in fragmented societies: UBc Press.

- Booher DE, Innes JE (2002) Network power in collaborative planning. Journal of planning education and research 21(3): 221-236.

- Innes JE, Gruber J (2008) Planning styles in conflict. Dialogues in urban and regional planning 3: 242.

- Carmona M, Heath T, Tiesdell S, Oc T (2010) Public places, urban spaces: the dimensions of urban design: Routledge.

- Brabham DC (2009) Crowdsourcing the public participation process for planning projects. Planning Theory 8(3): 242-262.

- Vision-II (2013) Vision II Design Studio Report.

- Keys-Young-and-Urban-Initiatives (1996) Waterfront Geelong Design and Development Code. Geelong: City of Greater Geelong.

- ABS (2011) Census data: quick stats. Geelong code 203 (SA4).

-

Hisham E. A Participatory Model for the Regeneration of Australian Cities: The Case of Geelong. Glob J Eng Sci. 4(4): 2020. GJES. MS.ID.000595.

-

Crowdsourcing, Participatory governance, Urban regeneration, Waterfront regeneration, City development, Vision II project, Geelong city

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

- Abstract

- Planning for Urban Regeneration

- The city of Geelong

- Background: Vision I Urban Regeneration Project

- Vision II Urban Regeneration Project

- The Stakeholder Partnership

- Vision II Process (The Development Strategy)

- Target Population

- The Workshops

- Community Engagement

- Vision II Studio Group

- International Experts

- The Final Stage

- The Working Groups

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgement

- Conflict of Interests

- References