Review Article

Review Article

Concepts and Design of High Thrust Ion Propulsion Engine with Magnetic Field Induction

Todd Brower DDS, MA*

Assistant Professor-- Restorative Clinical Sciences, I Scholar—Physics, Instructor, University of Missouri-Kansas City, USA

Todd Brower DDS, MA, Assistant Professor-- Restorative Clinical Sciences, I Scholar—Physics, Instructor, University of Missouri-Kansas City, USA.

Received Date:October 07, 2025; Published Date:October 17, 2025

Abstract

We present a conceptual architecture for a high-thrust ion propulsion engine based on magnetic field induction, combining rotating magnetic fields (RMF), magneto-inertial fusion (MIF) heating, and magnetic nozzle acceleration. The aim is to reach “sub-light impulse” cruise velocities between 20,000 mph and 200,000 mph, establishing a practical bridge from classical ion propulsion to speculative pre-warp research. We outline the physics model, scaling laws, materials constraints, power and thermal budgets, and a stepwise technology roadmap. Five color figures visualize the roadmap, engine layout, warp-bubble context, plasma induction, and a composite final design.

Keywords:Ion propulsion; magnetic induction; Rotating magnetic fields (RMF); Magneto-inertial fusion (MIF); Magnetic nozzle; Alcubierre; Lentz; Casimir; EM drive; Sub-light impulse; Pre-warp

Introduction

Ion thrusters have demonstrated exceptional propellant efficiency but limited thrust. Missions that require rapid interplanetary transit or high-Dv operations motivate concepts that raise both exhaust velocity and thrust. We adopt the working label “sub-light impulse” for 20,000–200,000 mph (≈9–90 km/s) cruise speeds, suitable for fast logistics and outer-planet flybys. These velocities represent a significant step beyond chemical propulsion, positioning ion propulsion as a realistic bridge toward more advanced space travel concepts.

The challenge can be expressed by the classical thrust equation:

T = m * v_e

where T is thrust, m is the mass flow rate of the propellant, and v_e

is the effective exhaust velocity. Current ion thrusters achieve high

v_e but suffer from low m, resulting in limited thrust. Increasing

both requires innovative electromagnetic acceleration techniques.

Background and Prior Art

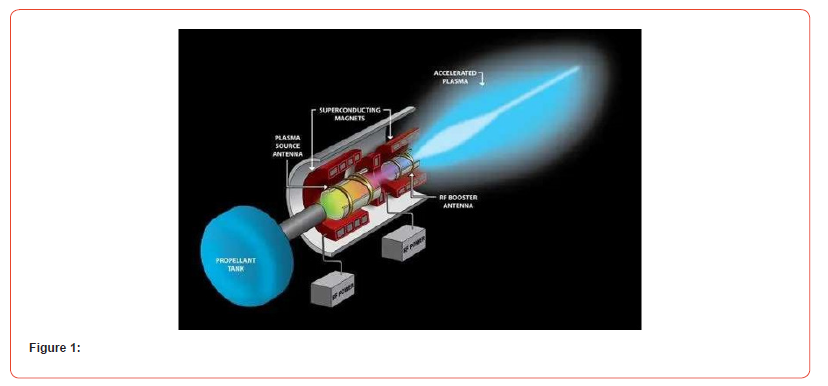

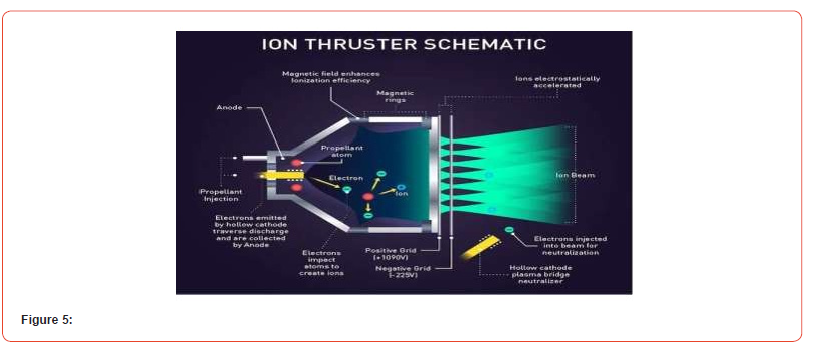

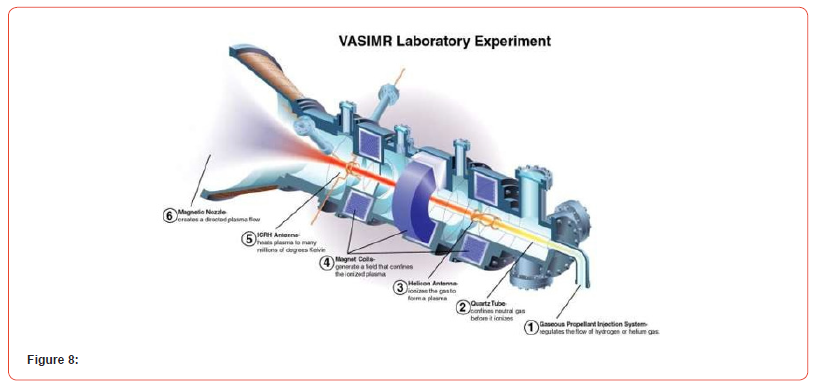

Electrostatic ion thrusters and Hall-effect thrusters accelerate ions using electric fields, while magnetic fields help to confine and shape plasma. However, erosion of grids and limited scalability restrict their lifetime. Concepts such as the Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket (VASIMR) and magnetic nozzles explore ways to achieve higher power densities.

Our concept extends these by employing RMF induction to accelerate ions inductively and by introducing fusion-adjacent heating (e.g., MIF) to increase plasma energy. This avoids electrode erosion and allows operation at higher temperatures and densities

High Thrust Ion Propulsion Concept

Conventional ion engines produce thrust by accelerating ions through electrostatic fields, yielding exhaust velocities on the order of ve∼30-50 km/sv_e \sim 30-50 \, \text{km/s}ve∼30-50km/s.

However, thrust is limited by both current density and power

supply. To achieve high-thrust ion propulsion with magnetic field

induction, the design integrates the Lorentz force to accelerate

plasma:

F⃗=q(E⃗+v⃗×B⃗)\vec{F} = q (\vec{E} + \vec{v} \times \vec{B})

F=q(E+v×B) Here:

• qqq = ion charge

• E⃗\vec{E}E = applied electric field

• B⃗\vec{B}B = induced magnetic field

• v⃗\vec{v}v = ion velocity

By inducing strong oscillating magnetic fields, ions can be accelerated magnetohydrodynamically HD) rather than solely electrostatically.

The thrust equation for ion propulsion is:

F=m˙veF = \dot{m} v_eF=m˙ve

where m˙\dot{m}m˙ is propellant mass flow rate and vev_eve is

exhaust velocity. Enhancing vev_eve via magnetic plasma acceleration

allows higher thrust without requiring exponential increases

in power.

For plasma confinement and acceleration, the magnetic pressure

balance is critical:

B22μ0≥nkBT\frac{B^2}{2\mu_0} \geq n k_B T2μ0B2≥nkBT

where nnn = plasma density, TTT = plasma temperature, and

BBB = magnetic field strength. This inequality ensures plasma

stability against thermal expansion, a key requirement for a highpower

ion drive operating at fusion-adjacent energy levels.

Sublight / Impulse Speed Regimes

Ion propulsion using magnetic induction could scale spacecraft velocities from 20,000 mph (~9 km/s) up to 200,000 mph (~90 km/s), which we term “sublight-impulse speed.”

The delta-v relation from the rocket equation applies:

Because ion drives achieve ve≫vchemicalv_e \gg v_{\text{

chemical}}ve≫vchemical, the achievable Δv\Delta vΔv is orders

of magnitude higher than with chemical propulsion.

Example: If ve=100 km/sv_e = 100 \, \text{km/s}ve=100km/s

with efficient magnetic acceleration, a spacecraft could theoretically

reach:

The appearance of snow cover is possible already at the beginning of September, but permanent snow cover is established in the first ten days of November. The average ten-day height of snow cover is 1-3cm. According to long-term observation data, the greatest height of snow cover was 33cm. The beginning of moisture saturation and melting of snow cover falls on the middle of February.

Δv≈100 km/s⋅ln(5)≈160 km/s\Delta v \approx 100 \, \text{ km/s} \cdot \ln (5) \approx 160 \,\text {km/s}Δv≈100km/s⋅ln( 5)≈160km/s or ~360,000 mph, well within the “pre-interstellar” regime.

Pre-Warp Engines: Toward Spacetime Manipulation

While magnetic field induction provides a scalable near-term solution, theoretical physics allows exploration of pre-warp concepts, where propulsion transitions from impulse-speed travel to spacetime engineering.

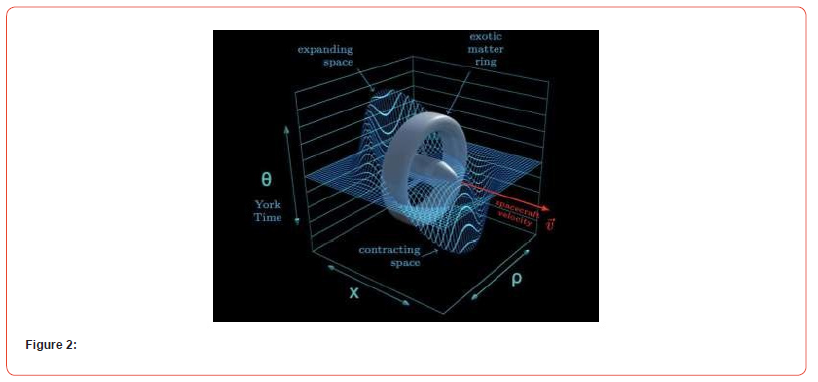

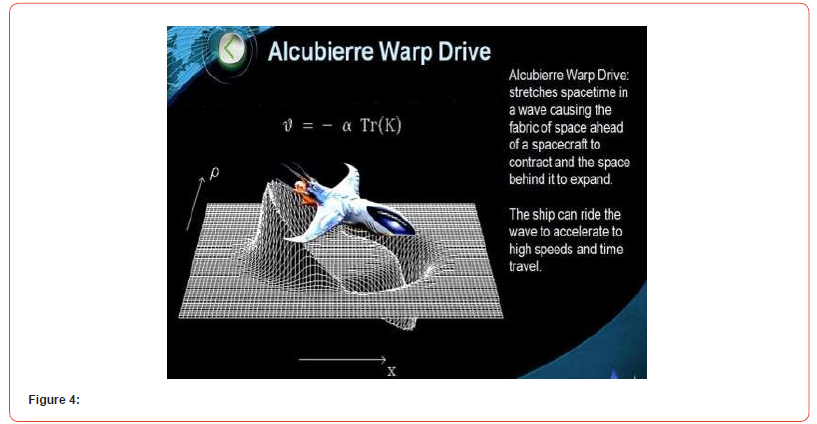

Alcubierre Metric (Warp Bubble)

The Alcubierre solution modifies spacetime by contracting it

ahead of the spacecraft and expanding it behind:

ds2=−c2dt2+[dx−vsf(rs)dt]2+dy2+dz2ds^2 = -c^2 dt^2 + \left[

dx - v_s f(r_s) dt \right]^2 + dy^2 + dz^2ds2=−c2dt2+[dx−vsf(rs)

dt]2+dy2+dz2

Here:

• vsv_svs: velocity of the warp bubble

• f(rs)f(r_s)f(rs): shaping function that defines the warp

bubble boundary This metric allows apparent superluminal travel

without locally exceeding ccc.

Energy Conditions

Originally, Alcubierre’s model required negative energy density, linked to exotic matter. However, Lentz (2021) proposed a class of soliton solutions that could create similar spacetime structures with only positive energy densities, relying on high-intensity electromagnetic or plasma field configurations.

A magnetically induced ion-plasma field could theoretically provide the energy-density gradients necessary for such configurations, serving as a pre-warp induction engine.

Engineering Roadmap

• Near-Term (0-20 years): High-thrust magnetic ion engines

(fusion-assisted VASIMR, rotating magnetic fields)

• Achieve 20,000-200,000 mph velocities

• Mid-Term (20-50 years): Hybrid ion–fusion propulsion

• Experimentation with field-induced spacetime distortions

at laboratory scales

• Long-Term (50+ years): Pre-warp ion–magnetic induction

systems

• Controlled spacetime engineering (Alcubierre/Lentzclass

metrics)

• Interstellar travel

8a. Physics Model and Scaling

For near-vacuum operation, thrust is approximated as:

T ≈ m * v_e

Power is related to exhaust velocity by:

P ≈ (m * v_e²) / (2η)

which shows that for a fixed power level, increasing exhaust velocity

reduces thrust. The trade-off between specific impulse (I_sp)

and thrust is thus central:

I_sp = v_e / g

where g is standard gravity (9.81 m/s²).

In RMF devices, rotating magnetic fields generate azimuthal

electric fields:

E_θ = -∂B/¶t

which induce currents J in the plasma. The force on charged

particles follows the Lorentz law:

F = q(E + v × B)

and on a macroscopic scale, the plasma experiences:

F=J×B

This provides the axial acceleration required for thrust.

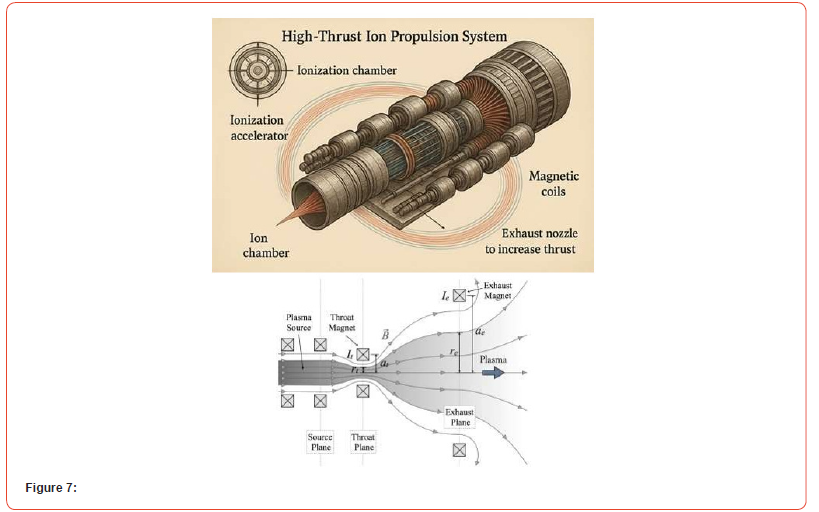

High Thrust Ion Propulsion Design Concept

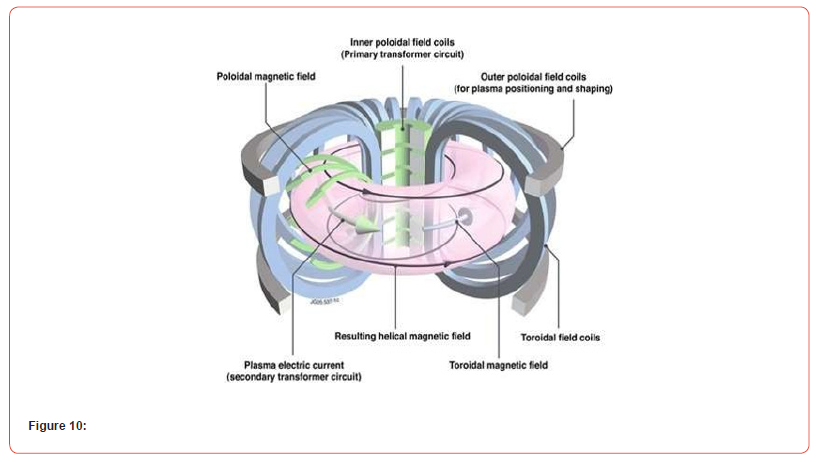

Rotating Magnetic Field Acceleration

One proposed design utilizes a rotating magnetic field (RMF) to

both ionize and accelerate propellant plasma. The concept draws

on principles of rotating magnetic fusion plasmas used in experimental

confinement devices.

• Primary Coil System: A set of superconducting coils generates

a strong axial magnetic field.

• Secondary RMF Coils: A phased array of coils around the

acceleration chamber produces a transverse rotating magnetic

field, creating azimuthal plasma currents.

• Plasma Dynamics: The RMF induces an electron drift,

which transfers momentum to ions via Coulomb collisions,

yielding axial acceleration.

The governing equation for the acceleration force per ion is:

F=q(E+v×B)F = q (E + v \times B)F=q(E+v×B)

where the effective accelerating field is enhanced by the rotating

component of BBB.

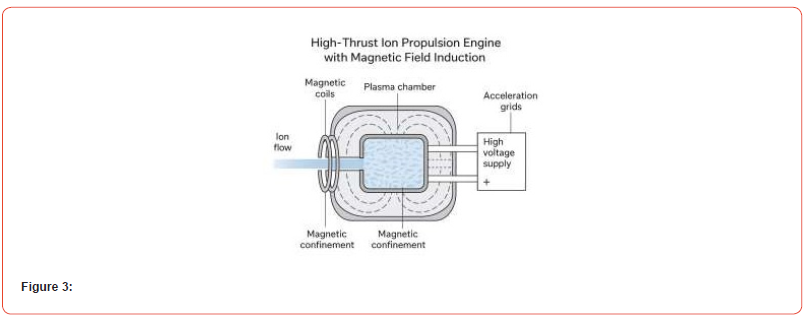

Engine Chamber Design

1. Ionization Zone – Neutral propellant gas (e.g., xenon, argon,

or hydrogen for fusion-assist) is injected and ionized via

RF or microwave power.

2. RMF Acceleration Zone – The rotating magnetic fields

couple with the plasma, inducing azimuthal currents and accelerating

the ions axially.

3. Magnetic Nozzle – A divergent magnetic field geometry

converts plasma thermal/magnetic energy into directed thrust,

analogous to a de Laval nozzle in chemical rockets.

4. Energy Recovery & Stability Controls – Magnetic mirrors

and feedback-controlled coils regulate instabilities, preventing

plasma losses.

Proposed Fabrication Approach

• Materials: High-temperature superconductors (HTS)

such as YBCO tapes for coil windings, enabling sustained

multi-tesla fields with minimal cryogenic load.

• Chamber: Carbon–carbon composites and tungsten coatings

for plasma-facing surfaces, resistant to erosion.

• Power Source: Compact nuclear fusion (magneto-inertial

fusion or aneutronic proton–boron concepts) or advanced fission

reactors for sustained gigawatt-scale output.

• Modularity: Engine modules can be clustered (like ion

drive “banks”) to scale thrust for larger spacecraft.

• Control Electronics: AI-assisted plasma diagnostics and

field control circuits dynamically adjust RMF frequencies (typically

in MHz range) to optimize confinement and thrust efficiency.

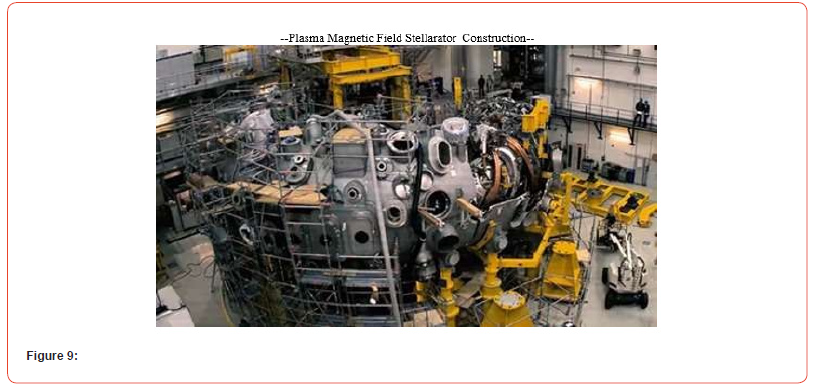

The fabrication design relies on existing plasma physics techniques (RMF drive coils, fusion chamber materials) adapted from tokamak and stellarator technologies, but miniaturized and optimized for propulsion rather than energy extraction.

Power, Thermal, and Materials

Operating at megawatt-class power requires compact, reliable energy sources (e.g., nuclear fission reactors, beamed microwave/ laser power, or compact fusion). Superconductors reduce resistive losses, but cryogenic systems must maintain stability under radiation.

Thermal management is critical. Heat pipes, liquid metal coolants,

and high- emissivity radiators dissipate waste heat. The Stefan–

Boltzmann law governs radiator performance:

P_rad = eσAT

where is emissivity, σ is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant, A is

area, and T is radiator temperature.

Performance Estimates

Toward 200,000 mph representative

velocities include:

- Entry sub-light: 20,000 mph (~9 km/s) - Mid sub-light:

100,000 mph (~45 km/s) - Upper sub-light: 200,000 mph (~89

km/s)

The mission Dv requirements can be related to exhaust velocity

using the rocket equation:

Dv = v_e * ln(m / m_f)

where m is initial mass and m_f is final mass.

Achieving 200,000 mph requires exhaust velocities in the 60- 120 km/s range, feasible with advanced EM accelerators. With multi-megawatt power and η ≈ 0.7, short-duration Mars missions and rapid outer-planet flybys become possible.

Pre-Warp Context: Alcubierre and Lentz

Warp drive concepts such as the Alcubierre metric propose spacetime contraction in front of a craft and expansion behind, allowing effective faster-than-light travel while remaining locally subluminal. However, energy requirements remain enormous and speculative.

While our engine does not achieve warp, it develops enabling technologies: high-field superconductors, energy-dense plasma drivers, and magnetic-field control. These may inform future experiments in pre-warp physics.

Current Theorized Relationships between Electromagnetism and Gravity— General Relativity and Quantum Mechanics: [background and some history]

*Our current theory assesses experimental and theoretical evidence that point toward a relationship between electromagnetism and gravity and/or general relativity and quantum mechanics. However, some results appear to imply connections to other areas outside of these, so please return for updates. (For a quick reference to the main papers, follow research by Dr. Don Mitchell)

Our first solution was for the effect noted in the Pioneer 10 and 11 space probes. NASA reported that the probes are being slowed by anomalous force that is constant with distance. However, the force did not show up in the orbits of the planets. General relativity predicts that light (electromagnetic energy) should produce a curvature of the space-time continuum, producing a gravitational effect. We formulated an equation describing the effect.

The acceleration a is proportional to the wavelength or frequency of the light. Planck’s constant is placed in brackets to indicate that it is a dimensionless constant. Treating the sun as a black body that emits radiation according to Planck’s radiation formula, the highest energy photons emitted by the sun are responsible for the effect seen in the probes. Overall, it can be called a kind of photo- gravity effect, analogous to the photoelectric effect.

Our explanation as to the reason why the effect is absent in the planets is that they are able to gravitationally attenuate the force by changing the frequency of the light as it approaches them. We treat the acceleration as a separate variable however; so as the energy of a photon increases as it approaches a planet due to gravitational red-shift, the gravitational force associated with its energy decreases. Thus a planets mass can effectively mask the effect seen in the probes. Our explanation appears supported by the Pound and Rebka experiment conducted at Harvard in 1960, and in particular, the anomalous acceleration affecting the Lageos satellites orbiting the earth.

Encouraged by our results, we have derived an expanded version of our equation to include Einstein’s formula that relates energy to mass to make a complete expression for the relationship between electromagnetism and gravity not only in terms of electromagnetic waves, but matter as well.

The equation we use as a substitute for mass in Einstein’s equation is the same as that used in the Compton Effect. Planck’s constant is held as a dimensionless constant of proportionality between the two states of energy and matter.

Now it is theorized that space-time is curved due to either the

presence of mass or energy. Thus, the metric that describes the ‘degree’

of curvature (or magnitude of the acceleration produced for a

given energy) would be the formal starting point in deriving a relationship

between electromagnetism and gravity. However, if acceleration is quantized (Being dependent on the frequency of

a light source rather than its intensity) it may imply the following

considerations:

Does the behavior of the Pioneer probes indicate a relationship

between electromagnetism and gravity and/or general relativity

and quantum mechanics? Light pressure is given by the equation

P=U/c for an object that totally absorbs all light and P=2U/c for a

totally reflective object. If the gravitational effect on the

probes is constant because it is proportional to the quantum

nature of light, can their behavior be categorized as a simultaneous

consequence of both the wave nature and particle nature of light?

Do the LAGEOS satellites, in conjunction with the Pioneer effect, indicate that the gravitational effect due to light may be treated as a separate variable? The anomalous force affecting the Pioneers is directed toward the Sun; the LAGEOS anomaly is directed toward the Earth. Does this indicate that a body (such as the Sun or Earth) becomes the gravitational frame of reference of a craft that lies within its immediate influence?

The gravity field of a mass “passes through” matter and energy. The law of superposition also holds for the gravity field of numerous masses. The same seems to apply, with one possible exception possibly indicated by the LAGEOS satellites. Where the gravity field of a mass might be viewed as being entangled with the mass, gravity due to energy (apparently) occurs only where the energy in question permeates space-time.* All this leads to what could be encountered by high thrust ion magnetic field plasma engines with stronger electromagnetic-gravitional fields/bubble/warping of space in front of a craft, entering a spacetime contraction, and thus moving thru a bending of space to travel great distances. (* to * is excerpt from Dr. Don Mitchell)

Technology Roadmap and TRLs

-Short term (TRL 3-4): Laboratory RMF thruster prototypes,

magnetic nozzle testing.

-Medium term (TRL 5-6): 100-500 kW integrated demos, flight

tests on cargo vehicles.

-Long term (TRL 6+): Megawatt-class spacecraft propulsion, fusion-

assisted RMF systems, velocities up to 200,000 mph, groundwork

for warp-adjacent research.

Risks, Testbeds, and Safety

Risks include plasma instabilities, superconducting coil quenches, radiation exposure, and material erosion. Mitigation strategies include quench protection circuits, magnetic shielding, and advanced plasma diagnostics (e.g., Langmuir probes, interferometry). Remote vacuum testbeds are recommended for safety validation.

Summations, Clarifications, and Closing Bullet Points

High-thrust ion propulsion engines represent a promising avenue for interstellar travel within human technological reach. This paper explores a design framework integrating magnetic field induction with plasma energy-fusion mechanisms, enabling both sub-light impulse speeds (20,000-200,000 mph) and pre-warp operations for interstellar propulsion. Additionally, theoretical extensions toward warp-bubble formation and space-time distortion are discussed, including Rotating Magnetic Field (RMF) thrusters, Magneto-Inertial Fusion (MIF) systems, and Quantum Vacuum Propulsion mechanisms.

A. Introduction

Interstellar propulsion is constrained by both the energy available

and the limitations imposed by relativity. Sub-light high-thrust

ion engines provide a practical intermediate step, offering speeds

sufficient for rapid solar system transit. Magnetic field induction

enhances ion acceleration efficiency and can potentially interact

with local space-time geometry when coupled with high-energy

plasma fusion. This work examines a hybrid approach combining:

1. High-thrust ion acceleration

2. Magnetic field induction

3. Plasma energy-fusion cycles

4. Theoretical pre-warp field generation

B. Sub-Light Impulse Propulsion (20,000–200,000 mph)

Sub-light impulse engines serve as a bridge between chemical/

ion propulsion and speculative warp drives. Key design considerations

include:

• Ion acceleration: Electrostatic and electromagnetic grids for

ion extraction and acceleration

• Propellant choice: Xenon, krypton, or lithium plasma for

high specific impulse

• Magnetic confinement: Toroidal magnetic fields maintain

plasma density and reduce erosion of grids

• Thrust vectoring: Controlled via variable magnetic fields

C. Pre-Warp Engines and Space-Time Manipulation

Pre-warp engines are conceptual systems that distort local

space-time to shorten effective interstellar distances without exceeding

relativistic speeds:

• Warp-bubble formation: Using induced electromagnetic

fields to create differential expansion/contraction of space

ahead and behind the craft

• Energy requirements: Coupling high-energy plasma fusion

with magnetic induction may theoretically reduce the negative

energy requirement

• Integration with ion engines: Sub-light engines provide stable

thrust while magnetic field interactions generate localized

curvature Figure 6

D. Magnetic Field Induction in Ion Engines

Magnetic induction can significantly enhance ion acceleration:

• Rotating Magnetic Field (RMF) Thrusters: Produce

high-density plasma rotation, improving thrust-to-power ratio

• Magnetic nozzle design: Converts plasma kinetic energy to

directional thrust efficiently

• Feedback control: Real-time monitoring of plasma density

and magnetic flux ensures stability

E. Plasma Energy-Fusion Induction

Incorporating a plasma fusion cycle can boost thrust while

opening theoretical pathways to space- time warping:

• Fusion fuels: Deuterium-tritium or advanced aneutronic fuels

• Magneto-Inertial Fusion (MIF): Pulsed magnetic compression

induces fusion with minimal mass penalty

• Plasma-field interaction: Induced high-energy plasma may

contribute to local curvature of space-time

F. Quantum Vacuum Propulsion and EM Drives

Advanced concepts include leveraging the quantum vacuum:

• Casimir effect: Exploiting vacuum energy differentials for

thrust

• EM Drive considerations: Controversial, but theoretically

compatible with magnetic plasma systems

• Integration: Hybrid systems may use residual EM fields to

reduce energy loss and improve thrust efficiency

G. Engineering Challenges

Key challenges include:

• Energy density management for plasma-fusion induction

• Heat dissipation under sustained high-thrust operations

• Material durability under intense magnetic fields Precision

control for pre-warp space-time manipulation

H. Outcomes

The integration of high-thrust ion propulsion, magnetic field induction, and plasma fusion represents a feasible pathway toward sub-light and pre-warp interstellar propulsion. While full warpdrive systems remain speculative, these hybrid engines provide a practical testbed for future exploration.

Conclusion

Magnetic-induction ion propulsion offers a credible route to simultaneously achieving higher thrust and high specific impulse, enabling sub-light impulse missions in the 20,000–200,000 mph range. While warp metrics remain speculative, the research advances field control and power management—fundamental requirements for any future attempt at spacetime manipulation [1-6].

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflicts of Interest

No Conflict of Interest.

References

- J Polk (2001) In-flight performance of the NSTAR ion propulsion system on NASA’s Deep Space One mission. AIAA.

- F F Chen (2016) Introduction to Plasma Physics and Controlled Fusion. Springer. In-flight performance of the NSTAR ion propulsion system on NASA’s Deep Space One mission.

- H D Curtis (2020) Orbital Mechanics for Engineering Students. Elsevier.

- H Daedalus (2015) The VASIMR Rocket. Journal of Propulsion and Power.

- M Alcubierre (1994) The warp drive: hyper-fast travel within general relativity. Class Quantum Grav.

- E Lentz (2021) Breaking the warp barrier: hyper-fast solitons in Einstein–Maxwell-plasma theory. Class Quantum Grav.

-

Todd Brower DDS, MA*. Concepts and Design of High Thrust Ion Propulsion Engine with Magnetic Field Induction. Glob J Eng Sci. 12(2): 2025. GJES.MS.ID.000785.

-

Magnetic field induction, Conceptual architecture, Velocities, Magnetic induction, Theoretical physics, Density, Positive energy, Negative energy, Quantum mechanics

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.