Case Report

Case Report

Hypoglycemia Masquerading Atypically as Hypertensive Urgency! A Call to De-Intensify Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes

Choi H and Dharmarajan TS*

Department of medicine, Division of geriatrics, Montefiore Medical Center (Wakefield Campus), University Hospital of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, New York, USA

Dharmarajan TS, Department of Medicine, Division of Geriatrics, Montefiore Medical Center (Wakefield Campus), Bronx, New York, USA

Received Date: January 13, 2020; Published Date: January 29, 2020

Case Report

When an older adult with multiple comorbidities including a history of long duration hypertension presents to the geriatrics clinic with markedly elevated blood pressure, several explanations are possible. The most common reasons typically suspected by health care providers are that the patient ran out of medications or there is non-adherence to antihypertensive medications for a variety of reasons. The following patient study demonstrates the reason can be simple and reversible, but potentially lethal if not addressed.

“An 80 years old female, with a long standing history of morbid obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) on basalbolus insulin (with a combination of insulin glargine 40 units daily and insulin aspart 5 units thrice daily with meals), mild cognitive impairment, compensated heart failure, anemia and stage 4 chronic kidney disease, was a regular follow up at our ambulatory geriatric clinic for years. She was known to have a good relationship with her providers and was mostly adherent to her medication regimen. This time, she complained of fatigue, mild dyspnea and a “vague sense of not feeling good”. The patient had recently lost her son from a chronic illness a few months earlier and had experienced a period of bereavement for several months; she had coped admirably. During this visit, her mood was not suggestive of depression during the evaluation.

On examination, she was awake and alert; vital signs were unremarkable except for significantly elevated blood pressure (BP) of 205/105 mm Hg. A repeat recording of the BP was 204/100 mm Hg. Her BP at home was around the same. Heart rate was 74/min. There was no clinical evidence of heart failure on examination; lungs did not reveal rales. Skin was not moist. There was no neurological deficit.The decision to hospitalize or treat as an outpatient was debated; as there was no evidence of organ damage, the patient was deemed to have “hypertensive urgency” and not hypertensive emergency. The dosage of antihypertensive medications (quinapril, carvedilol, nifedipine, clonidine and furosemide) was increased; in the absence of a clear explanation for her clinical course, routine laboratory tests were drawn and close follow up was recommended.

Next morning, verification of the laboratory reports revealed that the serum glucose drawn the prior evening was 29 mg%. The serum creatinine was 2.22 mg%, BUN 44 mg%, eGFR 23 ml/mt, and HbA1c was 9.1. Of note, when the patient had come to us a couple of years earlier, her HbA1c was over 12. On realizing the severe hypoglycemia, an immediate phone call to the patient revealed that she was fine, and that the BP was normal. On specific questioning, the daughter revealed that upon going home, the patient ate a good dinner and felt fine thereafter. Home finger stick for glucose following dinner was over 200 mg%. The follow up BP readings were now markedly lower than in the clinic. The dosage of insulin regimen was adjusted”.

The recent American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines states that hypertensive urgency, or severe asymptomatic hypertension, is defined as markedly elevated BP (systolic BP >180 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP >120 mm Hg) without acute target organ damage [1]. The management of such asymptomatic patients with hypertensive urgency may be usually carried out in the emergency room but can be attempted also in the clinic setting with close monitoring. However, in practice, outpatient management is often found to be challenging, because several patients are lost to follow up during evaluation in the clinic, as suggested by data from Studying the Treatment of Acute Hypertension (STAT) registry [2].

In our case, hypertensive urgency was eventually deemed to be a consequence of the severe hypoglycemia and related adrenergic or sympathomimetic stimulation. Hypoglycemia induced hypertensive urgency, is theoretically a diagnosis that can be made easily in the clinic setting. There is a relationship between hypoglycemia and elevated blood pressure; in fact, a close temporal relationship exists, based on a study [3]. Moderate or severe hypoglycemia decreases parasympathetic tone and predisposes to cardiovascular autonomic imbalance, with a relationship between severity of hypoglycemia and heart rate variability [4]. A human subject experiment demonstrated that insulin induced hypoglycemia causes elevation of blood pressure through sympatho-adrenal mechanisms [5].

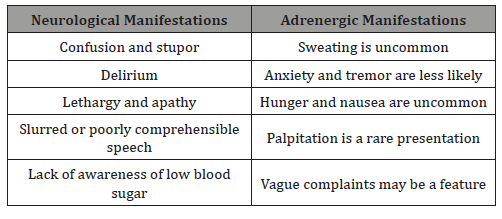

Age-related changes, decreased renal function, decreased breakdown of insulin, slowed intestinal transit and function, all predispose older adults, especially those on insulin therapy to greater risk for hypoglycemia [6]. Of clinical relevance, and importantly, a physiologic decline in autonomic nervous system regulatory function with age, [7] makes it more likely for older adults with hypoglycemia to experience neuroglycopenic manifestations, such as, confusion, fatigue, apathy, lethargy and delirium, as opposed to adrenergic features, such as sweating or tachycardia, the latter typically noted in younger adults Table 1 [8- 10]. Patients may also present with irritability, mood change, falls and seizures. Hunger, sweating and palpitations, while typical in the young, are rare in older adults, as demonstrated in our case, in whom they conspicuously absent. Further, older adults, especially those on insulin, are more vulnerable to hypoglycemia induced hypertension with poor autonomic function [7] (Table 1).

In summary, the manifestations of hypoglycemia in the elderly are vague or absent, and there is delay on the part of the patient in seeking help, as also a delay in providers suspecting the diagnosis. Our patient had sudden blood pressure elevation with vague manifestations, and in hindsight, all her manifestations appear related to severe hypoglycemia. Today, older adults with T2D are more likely to present to the emergency rooms of hospitals with hypoglycemia as compared to hyperglycemia. Medical expenses are reportedly increasing, as a result of emergency room visits and complications, including mortality relating to a preventable event, hypoglycemia [10,11]. Hypoglycemia can result in death!

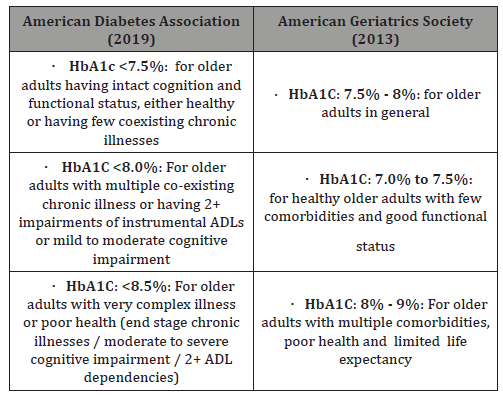

Health care providers should be mindful of the current American Diabetes Association guidelines relating to target HbA1C for different people. The recommendation is to set less stringent target HbA1C levels for older adults, and individualize the target based on several factors: patient characteristics and health status (healthy, complex illness, or very complex and poor health); life expectancy (long, intermediate or limited); and location (community, institutionalization, end-of-life); and accordingly set the A1C goal at <7.5 or <8.5 [10-12]. In particular, the presence of multiple comorbidities, limited life expectancy less than 10 years, longer disease duration, established vascular complications, lack of support systems, cognitive impairment, functional dependence and patient preferences should favor less stringent or higher A1c targets (10). More stringent or lower A1C targets would be favored in the opposite settings (Table 2).

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey involving U.S. adults with diabetes in the time period 2011- 2014 were most revealing [3], in that nearly half the 21,980,034 adults with diabetes (representing 10.7 million US adults), had HbA1c levels <7.0%. A third of these were clinically complex and 21.6% were intensively treated. Clinically complex patients refer to those age 75 years or older or with 2 or more activities of daily living limitation, 3 or more chronic conditions or end-stage renal disease. Over 2 years, 31,511 hospitalizations and 30,954 ED visits for hypoglycemia were observed, with 4774 hospitalizations and 4804 ED visits attributable to intensive treatment. The conclusion was that intensive glucose lowering therapy especially in vulnerable clinically complex adults is strongly discouraged [13]. The experience is highlighted in our patient’s story; she was fortunate and taught the providers of care much by way of learning.

Learning Points

i. Older adults with Type 2 DM and complex illness, especially those on insulin therapy, are vulnerable to hypoglycemia, an association with adverse outcomes, including hospitalization and mortality.

ii. When an older adult with diabetes on hypoglycemic agents presents with ill-defined manifestations, including unexplained elevation of blood pressure, the possibility of hypoglycemia must be among the initial considerations, while treating in the emergency department.

iii. Health care providers need to take precautions while treating older adults with Type 2 DM by maintaining HbA1c levels higher than in healthy younger people, to reduce the risk and burden of hypoglycemia [13].

References

- Whelton PK , Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, et al. (2018) 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension 71(6): e13-e115.

- Katz JN, Gore JM, Amin A, Anderson FA, Dasta JF, et al. (2009) Practice patterns, outcomes, and end-organ dysfunction for patients with acute severe hypertension: The Studying the Treatment of Acute hypertension (STAT) registry. Am Heart J 158(4): 599-606.

- Feldman-Billard S, Massin P, Meas T, Guillausseau PJ, Héron E (2010) Hypoglycemia-induced blood pressure elevation in patients with diabetes. Arch Intern Med170(9): 829-831.

- Silva TP Rolim LC, Sallum Filho C, Zimmermann LM, Malerbi F et al. (2017) Association between severity of hypoglycemia and loss of heart rate variability in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 33(2): E2830.

- Sommerfield AJ, Wilkinson IB, Webb DJ, Frier BM (2007) Vessel wall stiffness in type 1 diabetes and the central hemodynamic effects of acute hypoglycemia. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293(5): E1274- E1279.

- Ober SK Watts S, Lawrence RH (2006) Insulin use in elderly diabetic patients. Clin Interv Aging 1(2): 107-113.

- Hotta H, Uchida S (2010) Aging of the autonomic nervous system and possible improvements in autonomic activity using somatic afferent stimulation. Geriatr Gerontol Int 10(1): S127-S136.

- Matyka K, Evans M, Lomas J, Cranston I, Macdonald I, et al. (1997) Altered hierarchy of protective responses against severe hypoglycemia in normal aging in healthy men. Diabetes Care 20(2): 135-141.

- Cardona S, Gomez PC, Vellanki P1, Anzola I, Ramos C, et al. (2018) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of symptomatic and asymptomatic hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients with diabetes BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 6(1): e000607.

- American Diabetes Association (2019) Older Adults: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 42: S139-S147.

- Ida S, Kaneko K, Imataka K, Murata k (2019) Relationship between frailty and mortality, hospitalization, and cardiovascular diseases in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol 18: 81.

- American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus, Mangione CM, Moreno G, Geffen D, Blaum CS, Chun A, et al. (2013) Guidelines abstracted from the American Geriatrics Society Guidelines for Improving the Care of Older Adults with Diabetes Mellitus: 2013 update. J Am Geriatr Soc 61(11): 2020-2026.

- Mahoney GK, Henk HJ, McCoy RG (2019) Severe hypoglycemia attributable to intensive glucose lowering therapy among US adults with diabetes: Population-based study 2011-2014. Mayo Clin Proc 94(9): 1731-1742

-

Choi H and Dharmarajan TS. Hypoglycemia Masquerading Atypically as Hypertensive Urgency! A Call to De-Intensify Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes. Glob J Aging Geriatr Res. 1(1): 2020. GJAGR.MS.ID.000502.

-

Mild cognitive impairment, Machine learning, Reinforcement learning, Serious games, WarCAT, Brain training, Cognitive fingerprint, Algorithm

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.