Research Article

Research Article

A Scale Proposition on the Discourse Curiosity of Aging

Fahri Özsungur*

Department of Labor Economics and Industrial Relations,Mersin University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences,Turkey.

Fahri Özsungur, Department of Labor Economics and Industrial Relations,Mersin University Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences,Turkey.

Received Date: June 7, 2021; Published Date: June 23, 2021

Abstract

This study focuses on the effects of discourse on aging. Whether the discourse of aging causes curiosity of aging is revealed with this study. In order to create a survey of 10 questions to be applied to the participants, an item pool was created with 145 participants in Adana-Turkey. The data obtained with the item pool were transformed into 12 questions with the qualitative method (Conceptualization, Classification, Component analysis). 12 questions were voted by the committee of 7 academicians who experts in different fields were. A survey of 10 questions obtained as a result of the voting was applied to 121 participants selected from Hatay-Turkey for the pre-test. As a result, the sample of the study consisted of 112 adult individuals (40-50 years of age range). The study was carried out in Mersin, Turkey in 2021. The results of the study showed that the aging discourse caused curiosity in middle-aged individuals. According to the results obtained, measurement ranges/scores were determined to rate the discourse-based curiosity of the individuals. The participants’ discourse-based aging curiosity was at a high level. In the context of sensitivity to aging, it was determined that the participants were moderately sensitive.

Keywords: Aging discourse; Aging curiosity; Discourse curiosity scale; Social work; Social policy

Introduction

While today’s elderly population is increasing rapidly, the effect of aging on individuals is also increasing. The super-aging population affects the socio-cultural and economic dynamics of many countries [1-3]. This acceleration, whose pressure on individuals, society, systems, and law is increasing, necessitated the development of important policies related to aging [4,5]. The principles developed with social work and social policy continue to seek solutions to the current problems of aging [6,7]. This seeking is not enough to solve the multi-factor structure of aging, which has critical effects on society and the individual. While the biological, social, economic, and physical effects of aging on individuals continue, many unknown questions about the factors based on curiosity and discourse are waiting to be answered [8-13]. What are the effects of discourse about aging on individuals? Does the aging discourse affect the curiosity of individuals? Answering these questions is the first step to explain the aging tendencies of individuals, their psychology, way of seeking information, and curiosity-based behavior. For this reason, the aim of the study is to reveal the curiosity behaviors of individuals against discourses about aging and to guide researchers in this regard. On the other hand, with the findings revealed as a result of the research, information that can inspire practitioners is obtained.

Methods

The qualitative and quantitative research method was adopted in the study (Mixed method) [14]. In order to reveal the effects (situation analysis) of aging discourse on aging curiosity, it was necessary to determine the questions of the survey. An extensive literature review was conducted to determine the survey questions [15]. Then, an interview was conducted with 145 participants in order to create a pool of questions and items that would form the basis of the survey questions. Questions about aging curiosity and discourse were asked to these participants, whose random sampling method was chosen in Adana, Turkey [16,17]. Participants were asked to write what “aging curiosity” and “aging discourse” mean to the online survey created via Google Form. 1842 unique words obtained from the participants were subjected to qualitative analysis (Conceptualization, Classification, Component analysis) [18-20]. The framework revealed by the results of the qualitative analysis focused on 12 basic questions. 12 questions were put to the vote of a committee of 7 academicians, who were experts in different fields. As a result of the voting, 2 questions were excluded. Ten questions were included in the study (Appendix).

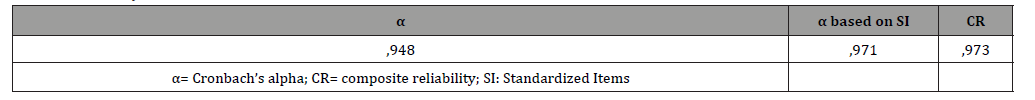

The final 10 questions were analyzed by a pre-test [21,22]. The pre-test was carried out with 121 participants selected by random sampling method in Hatay, Turkey. A 5-point Likert-type scale was applied in the questionnaire (1=Strongly disagree; 2=Disagree; 3= Neutral; 4=Agree; 5=Strongly agree). The obtained results were evaluated in terms of validity and reliability. According to the results of exploratory factor analysis, inter-item correlations were calculated above 0.4. Cronbach’s alpha values of the items were calculated over .90 [23-24] (Table 1).

Table 1:Reliability Statistics.

Since the study is not the development of a scale (a scale proposition), all steps of the scale development were not implemented. For this reason, it is thought that the results (related to the validity and reliability of a quantitative method) will be a source of inspiration during the scale development phase. According to the pre-test results, Discourse Curiosity of Aging (DCA) and demographic information questions consisting of 10 questions were applied to 112 middle-aged individuals aged 40-50 in Mersin, Turkey, by random sampling method. The reason why the age range of 40-50 is preferred is to measure the curiosity behaviors of individuals against the discourse regarding aging. These perceptions of elderly individuals might not make a significant difference due to insensitivity. However, researching this subject for future studies can provide important contributions to the literature.

Findings

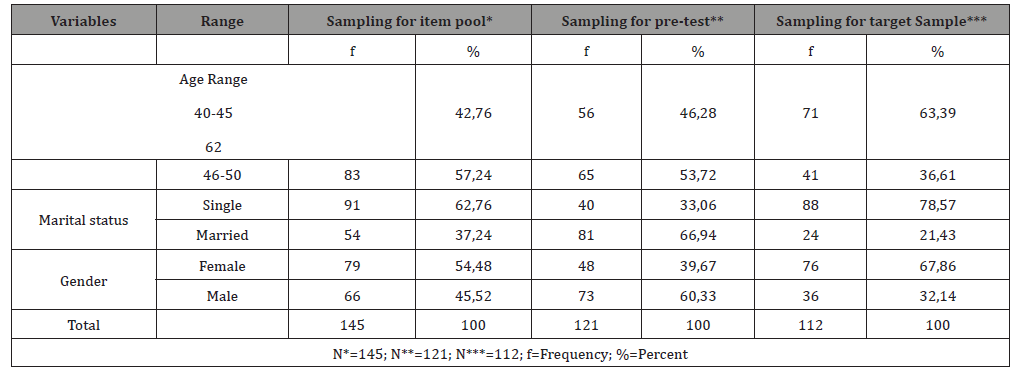

Demographic information according to the survey results applied in the study is shown in Table 2. As can be seen from the table, in the sample determined to create an item pool, 46-50 age range, single, and female participants were more than other groups. In the study conducted for the pre-test, there were more married, male and 46-50 age range participants compared to the other groups (Table 2).

Table 2:Demographic Variables.

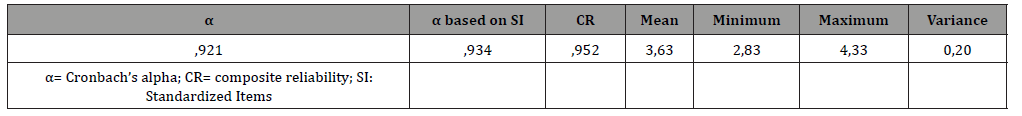

Finally, among the 112 participants, who constitute the final sample of the current study, there were more 40-45 age range, single and female participants compared to other groups. Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, Cronbach’s Alpha Based on standardized items, mean, minimum, maximum, and variance values of the scale were calculated for the discourse curiosity of the aging status of the participants, which was tried to be measured with 10 questions. Calculated values for items are presented in (Table 3).

Table 3:Reliability and item statistics.

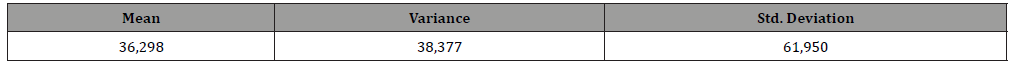

Table 4 presents the statistical values of the scale. According to the findings, participants’ discourse-based curiosity about aging was determined at a high level (Table 4).

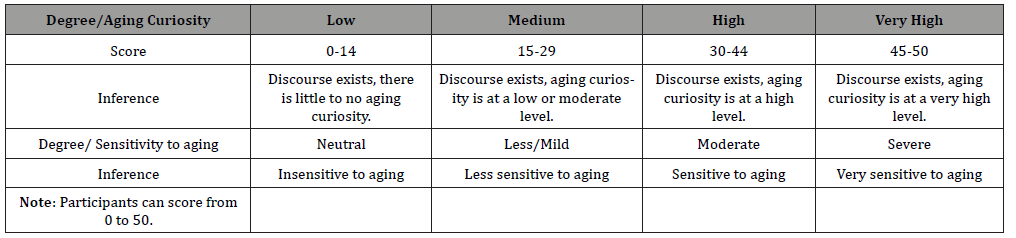

According to the results obtained, measurement ranges/scores were determined to rate the discourse-based curiosity of the individuals. This measuring range is shown in (Table 5).

Table 4:Scale Statistics.

Table 5:DCA scores and degrees.

When the results of the research and Table 5 are evaluated together, it can be said that the participants’ discourse-based aging curiosity was at a high level. In the context of sensitivity to aging, it was determined that the participants were moderately sensitive.

Discussion and Conclusion

Aging is a multidisciplinary field [25]. Studies in the literature emphasize the social, physical, cultural, biological, medical, and economic aspects of aging [26]. In the studies, the effects of discourse on aging have not been examined. This is an important shortcoming for the aging literature. Because discourse is a phenomenon that has critical effects on the individual and society. Discourse-based psychology of individuals can change, revealing informationseeking behaviors [27,28]. Curiosity is one of the reasons for knowledge-seeking [29]. News and columns about aging in visual, written, and virtual media can trigger the curiosity of individuals [30]. Thus, the information that needs to be learned about aging can cause curiosity based on discourse other than motivation [31,32]. The discourse-based curiosity revealed by the findings of our research reveals an important situation regarding aging. The fact that individuals between the ages of 40-50 (middle-aged) are extremely sensitive to the aging discourse triggers their curiosity on this subject. This can have significant medical, psychological, social, and cultural consequences. The findings of the study aim to be an inspiration point for future studies on aging. The scale can be developed based on the items suggested in this regard. Thus, the relationship between the scale to be developed and different scales can be tested. It is recommended that future studies be applied to different samples with the questions raised by the research. It may also be interesting to examine the effects of this scale on elderly individuals. Although the research is not a scale development study, it is groundbreaking as it aims to reveal the current situation and there is no similar study in the literature on this topic. Although the necessary statistical methods were followed in determining the sample, determining the factor loadings as a result of the exploratory factor analysis of the study with a larger sample size and revealing its dimensions will make significant contributions to the literature. Many aging theories claim that aging is a process. However, the aging-related effects of curiosity and discourse, which affect human psychology, need to be developed theoretically. On the other hand, the effects of discriminatory and violent discourses about aging on individuals should not be ignored in the theories to be developed. In addition, the curiosity-based effects of discourse on middle-aged individuals should be taken into account by policymakers. Social work and social policy should take a leading role in taking the necessary measures in this context.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- Muramatsu N, Akiyama H (2011) Japan: super-aging society preparing for the future. The Gerontologist 51(4): 425-432.

- Park S, Yang MJ, Ha SN, Lee JS (2014) Effective anti-aging strategies in an era of super-aging. Journal of menopausal medicine 20(3): 85-89.

- Özsungur F (2020a) Super Aging. Turkish Journal of Social Work Research 4(3): 37-43.

- Gruber J, Wise D (2001) An international perspective on policies for an aging society (No. w8103). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Heller T, Caldwell J, Factor A (2007) Aging family caregivers: Policies and practices. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 13(2): 136-142.

- Berkman B (2006) Handbook of social work in health and aging. Oxford University Press.

- Barbara Berkman DSW (2003) Social work and health care in an aging society: Education, policy, practice, and research. Springer Publishing Company.

- Liu D, Xi J, Hall BJ, Fu M, Zhang B, et al. (2020) Attitudes toward aging, social support and depression among older adults: Difference by urban and rural areas in China. Journal of Affective Disorders 274: 85-92.

- Bai C, Lei X (2020) New trends in population aging and challenges for China’s sustainable development. China Economic Journal 13(1): 3-23.

- Liang J, Luo B (2012) Toward a discourse shift in social gerontology: From successful aging to harmonious aging. Journal of aging studies 26(3): 327-334.

- Rozanova J (2010) Discourse of successful aging in The Globe & Mail: Insights from critical gerontology. Journal of aging studies 24(4): 213-222.

- Sakaki M, Yagi A, Murayama K (2018) Curiosity in old age: A possible key to achieving adaptive aging. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 88: 106-116.

- Swan GE, Carmelli D (1996) Curiosity and mortality in aging adults: A 5-year follow-up of the Western Collaborative Group Study. Psychology and Aging 11(3): 449-453.

- Caracelli VJ, Greene JC (1993) Data analysis strategies for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational evaluation and policy analysis 15(2): 195-207.

- Sandelowski M (2000) Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed‐method studies. Research in nursing & health 23(3): 246-255.

- Marshall MN (1996) Sampling for qualitative research. Family practice 13(6): 522-526.

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Leech NL (2007) Sampling designs in qualitative research: Making the sampling process more public. Qualitative Report 12(2): 238-254.

- Khoshnaw SH, Shahzad M, Ali M, Sultan F (2020) A quantitative and qualitative analysis of the COVID–19 pandemic model. Chaos Solitons & Fractals 138: 109932.

- Strauss AL (1987) Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge university press.

- Glaser BG (1965) The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social problems 12(4): 436-445.

- Eldar YC, Chernoi JS (2008) A pre-test like estimator dominating the least-squares method. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference 138(10): 3069-3085.

- Bloomfield J, Fisher MJ (2019) Quantitative research design. Journal of the Australasian Rehabilitation Nurses Association 22(2): 27-30.

- Fabrigar LR, Wegener DT (2011) Exploratory factor analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Cudeck R (2000) Exploratory factor analysis. In Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling pp. 265-296.

- Kendig H (2003) Directions in environmental gerontology: A multidisciplinary field. The Gerontologist 43(5): 611-615.

- Özsungur F (2020b) Successful Aging Management in Social Work. OPUS Uluslararası Toplum Araştırmaları Dergisi 15(1): 5277-5307.

- Mills S (2006) Discourse. Routledge.

- Tseliou E (2020) Discourse Analysis and Systemic Family Therapy Research: The Methodological Contribution of Discursive Psychology. In Systemic Research in Individual, Couple, and Family Therapy and Counseling pp. 125-141.

- Kim K, Sano M, De Freitas J, Haber N, Yamins D (2020) Active World Model Learning with Progress Curiosity. In International Conference on Machine Learning pp. 5306-5315.

- Scacco JM, Muddiman A (2020) The curiosity effect: Information seeking in the contemporary news environment. New Media & Society 22(3): 429-448.

- Daffner KR, Scinto LF, Weintraub S, Guinessey J, Mesulam MM (1994) The impact of aging on curiosity as measured by exploratory eye movements. Archives of Neurology 51(4): 368-376.

- Caracelli VJ, Greene JC (1993) Data analysis strategies for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educational evaluation and policy analysis 15(2): 195-207.

-

Fahri Özsungur. A Scale Proposition on the Discourse Curiosity of Aging. Glob J Aging Geriatr Res. 1(3): 2021. GJAGR.MS.ID.000515.

-

Aging discourse; Aging curiosity; Discourse curiosity scale; Social work; Social policy

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.