Research Article

Research Article

Review of Osteoarthritis Depressive Associations 2024-2025 and Their Implications

Ray Marks, Osteoarthritis Research Center, Canada

Received Date:February 11, 2024; Published Date:February 19, 2025

Abstract

Background: Is osteoarthritis, a generally progressive incurable disabling health condition, more than a physical age associated disease?

Aim: The first aim of this brief review was to examine the research base published between January 2024-February 2025 concerning the nature

and prevalence of depression in older adult populations suffering from osteoarthritis. A second was to provide directives for professionals likely to

work with this population in the future.

Methods: Building on several prior reviews, all 2024/5 English language peer reviewed publications detailing some aspect of depression in

cases suffering from osteoarthritis among the elderly were sought and examined. Key words used were: osteoarthritis, older adults, and depression.

Databases employed were PubMed and Google Scholar.

Results: Collectively, these data reveal many older adults with osteoarthritis may become depressed as a result and that efforts to reduce and

mitigate pain may be very useful as a rehabilitation strategy for older people with different degrees of depression, regardless of strategy employed.

Conclusions: Older individuals with chronic osteoarthritis and depressive symptoms do suffer mentally, socially, and emotionally to a high

degree, and can benefit emotionally from strategies to reduce pain, regardless of cause and overall health status.

Keywords: Aging Adults; Depression; Disability; Osteoarthritis; Pain; Therapy

Introduction

Among the many health challenges impacting life quality, life related goals, one’s general wellbeing, and social interactions quite adversely in multiple older population is the prevalent health condition termed osteoarthritis, the most common form of the many painful and disabling joint diseases [1-3]. Affecting one or more freely moving joints such as the knee joint, the progressive and oftentimes widespread and largely irreversible cumulative pathological features of the condition, especially pain, plus lowgrade inflammation, joint instability and muscle weakness appear to induce mental as well as cumulative and debilitating physical health and functional challenges that are not well understood and hence hard to target, or obviate or reverse [1,4,5]. It is also possible that this situation is indeed more common than not and is potentially remediable to some degree, but is often unfortunately underestimated, possibly not evaluated –hence- underreported, or assessed superficially using less than robust measures [2].

These who suffer from multiple medical comorbidities that can worsen over time in the face of unrelenting osteoarthritis pain, such as obesity [6,7], as well as primary psychiatric conditions including depression [1, 2,8], a widespread health concerns in its own right may not be seen as being related to osteoarthritis disability and pain [9] and especially osteoarthritis progression [10-13]. In the meantime, those who report feeling depressed in some way appear to experience more pain than those who do not report this before surgery [14], while certain modes of knee surgery may yet induce depression or fail to relieve this [15] and prove a limiting factor to the surgical recovery progress [16-20]. Depressive feelings that generate sadness, a loss of interest and pleasure in daily activities, feelings of hopelessness, and low self-worth may not only limit treatment efficacy and options, but conceivably can greatly reduce motivation for self-care and self-protection that is paramount to health maintenance. In addition, as with older adults and others suffering from depression those with osteoarthritis may experience poor sleep patterns, fatigue, excessive catastrophizing, interference with their daily activities, and appetite losses. They may experience elevated pain levels and poor functional self-efficacy [21], as well as resilience and life quality deficits [22] that hasten declines in other body systems [23].

Given that osteoarthritis is increasing in prevalence and costs

it seems its mental health impacts warrant attention [24]. This

report examines the current status of this issue regarding the

magnitude and apparent role of feelings of depression, a potentially

modifiable factor in the pathway from osteoarthritis pathology to

disability [25], with a view to rendering possible recommendations

for advancing clinical practices in this area. To this end, this review

describes: what is currently observed as regards depressive

symptoms in the adult affected by osteoarthritis, and which may

occur independently as a separate longstanding health condition, or

in reaction to the persistent presence of other illnesses, adverse life

events and losses, and mobility losses. Accordingly, this discussion

focuses on:

1. Some key features of osteoarthritis.

2. Findings concerning osteoarthritis and depression

3. Strategies that might help decrease depressive symptoms.

4. Implications for practice and research.

Significance

Consistent with the need for continuing efforts to broaden our knowledge base concerning factors that impact osteoarthritis disability, particularly with respect to the long term prognosis the topical information sought on depression linkages and osteoarthritis was also deemed consistent with the goal of identifying what prevention/intervention strategies other than those currently considered standard practice might prove efficacious in the future for maximizing the affected individuals’ functional status and overall life quality, while minimizing the extent of the anticipated disease progression. Commonly a neglected area of therapeutic concern, and often not even mentioned in the context of clinical practice recommendations, the author’s purpose was to provide a firm rationale for supporting continuing efforts in this regard.

Accordingly, in the first section of this work, some background information on the topic of osteoarthritis followed by the topic of depression and the linkage of depression to common symptoms associated with osteoarthritis of one or more joints is presented. Then some recent data from clinical observations of selected cohorts classified as having osteoarthritis is presented. The work concludes by summarizing the key findings from these data and by providing related guidelines for clinical practice and future research endeavors, even if not explicitly mentioned in a consortium based 2024-2028 joint plan to address osteoarthritis [26], but supported by Zhang [27] based on past literature.

Methods

The desired information was compiled from an extensive review of the English language literature embedded in PubMed and Google Scholar over the period January 1 2024-February 4 2025 and to build on prior knowledge. The goal was to examine the current emergent research observations and estimate if any progress has been made on this previously underreported issue of the link between the onset of feelings of depression and osteoarthritis disability and outcomes and intervention opportunities. Using the keywords: Osteoarthritis and Depression, the following reports were deemed both enlightening and acceptable and are duly narrated in descriptive form due to their diversity, and largely dissimilar cross-sectional study designs or retrospective analyses that examine only selected attributes and omit others small heterogeneous samples with variable degrees of measurement validity and modes of instrument usage. Articles that discussed rheumatoid or other form of arthritis and those that assessed depression as a surgical outcome rather than a presurgical disabler were not pursued to any degree. Due to their unclear distinctions, all forms of depression and modes of verifying its presence were deemed acceptable, as were all forms and degrees of osteoarthritis. The broad target population of interest was older adults and the need for study and its importance is currently supported in Zhang [27], Fonseca-Rodriguez et al. [28], Rathbun et al. [29] and Del Val et al. [30] and can be referred to for past and topical references of note.

Results

In line with most past reports, most current reports including 215 related citations housed between January 2024-2025 and related to osteoarthritis and depression continue to state that osteoarthritis commonly produces lengthy periods of chronically intractable pain experiences, joint stiffness and swelling, as well as multiple functional, social, occupational, and emotional challenges and restrictions, plus a low life quality, as well as feelings of depression. Although not a ‘death sentence’, its significant overlapping interconnected negative physical, economic, psychological, inflammatory, pain, and social impacts are often progressive, and impervious to most interventions if not diagnosed early on [31]. This is not a sporadic finding but one increasingly observed in those affected, who often represent a sizeable proportion of the older adult population and one likely to have multiple health challenges as well as fewer physiological abilities to combat its diverse impacts. While it is encouraging that some articles examine depression as a disease attribute to some extent in efforts to comprehend the disease impacts, and opportunities that may reduce the magnitude of osteoarthritis pain or help to offset this where apparent or predictable, such as those with mental health challenges [32], most fail to pinpoint or offer any definitive set of strategies for reducing osteoarthritis pain, the chief complaint of people with this condition, and a strong depression mediator. In this regard, it appears most current articles discussing intervention in terms of how to achieve more success, concur that more needs to be done in this sphere, and at earlier rather than a later disease stage [32,33]. Others show more needs to be done to treat both pain and depression in tandem as it seems worse outcomes and increases in pain sensitivity [34] are likely to prevail in those cases where mental health disturbances are evidenced, but are not accounted for [32,35]. Alternately, despite their meaningful findings, many current authors support the need to more successfully identify if the osteoarthritis patient is at risk for depression and if so, whether efforts to try to avert this accordingly would improve the disease outlook [30].

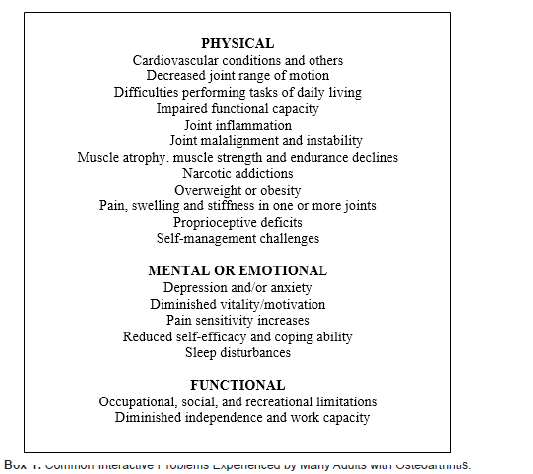

Nonetheless, one important observation put forth currently by multiple authors is that as opposed to previous beliefs and research practices that originally considered osteoarthritis to be solely a physical or biomechanical age associated problem [see Box 1], its emotional correlates have only recently been shown of additional value and high salience in explaining findings of declines in vitality, poor life quality, reduced cognitive and physical functioning and diminished work and wage earnings capacity among many older adults with one or more diseased joints and that may enhance the need for surgery [14, 33]. Moreover, in addition to associated ongoing mechanical disturbances, osteoarthritis may be accompanied by diverse degrees of vascular changes, soft tissue contractures, muscle spasm, crystal deposition, and disease related alterations in sensory inputs to the central nervous system. As such, it appears the onset of any pervasive pain experience, and a state of increasing intensity that often ensues is often accompanied by parallel bouts of reactive depressive, even if the actual extent of joint pathology itself is not striking and surgery is forthcoming.

However, it is also possible that depression that stems not only from a progressively emergent state of increased pain sensitivity, but is magnified in the event this attribute is ignored medically as a disability [9], as is its central nervous system influences including individual behaviours, predicts increases in pain sensitivity. This alone can result in feelings of helplessness, anxiety, and poor coping ability that can conceivably impact the degree of osteoarthritis pathology and treatment responsiveness, plus the level of adherence and self-efficacy for managing their disease, and sleep quality. In turn, data show this negative series of feedback responses to be significantly correlated with future pain and disability, regardless of the prevailing degree of osteoarthritis damage. In particular, this cycle of adverse health associations, especially anxiety, may similarly foster activity avoidance, and decreases in physical function [25], while generating a low sense of morale.

Compounding this may be osteoarthritis and its highly resistant nature, misconceptions in this regard, and basic beliefs engendered by medical organizations and personnel, as well as suboptimal interventions in the disease cycle even were indicated plus a lack of emphasis or any focus on the varied and complex role of cognitions both positive and negative on the disease cycle. For example, the experience of constant pain and increasingly difficulties in accomplishing everyday tasks, that can engender fatigue, as well as negative outcome expectations, may elicit persistent feelings of sadness, loss and distress as well as overall stress, feelings of hopelessness, and low self-worth. Moreover, older individuals already suffering from primary depressive symptoms may experience worse outcomes if they have osteoarthritis as well as possible sleep deprivation, poor sleep quality, an excessive exaggerated pain focus, interference with their daily activities, and appetite losses, alongside a greater likelihood of possible narcotics associated premature death. They may experience higher rates of local and systemic inflammation than desired, increased blood pressure, memory challenges, and a decreased desire for physical activities. Other emergent health implications may include weakness, anxiety, social withdrawal, and higher rates of bone loss, all factors that could interact to magnify the extent of osteoarthritis disability, and possible overuse of existing health systems and services. Even if somewhat negated as a key long term outcome determinant of note [29, 36] more evidence than not shows osteoarthritis cases who report depressive symptoms may develop more rapid disease progression, worsening structural severity or decreases in physical performance.

Sayre et al. [37] found knee osteoarthritis-related manifestations tended to predict depression and anxiety in both standalone examinations as well as those conducted in the future. Zheng et al. [39] found the presence and incidence of depression was 25.4 and 11.2%, respectively. At baseline, being younger, having a higher body mass index, and greater pain scores, dysfunction and stiffness, having a low education level, having more than one comorbid condition and having two or more painful body sites were significantly associated with a higher presence of depression. Over 24 months, being female, having a higher WOMAC pain and dysfunction score at baseline and having two or more painful sites were significantly associated with a higher incidence of depression. In contrast, baseline depression was not associated with changes in knee joint symptoms over 24 months. It was concluded knee osteoarthritis risk factors and joint symptoms, along with coexisting multi-site pain are associated with the presence and development of depression, thus managing common osteoarthritis risk factors and joint symptoms may be important for preventing and treating depression in cases with knee osteoarthritis even though Riberio et al. [40] found no significant relationship between the scores of the instruments, such as depression scores, investigated and the individual radiographic knee severity grades.

In a recent study [40] of 96 cases of people with knee osteoarthritis, 70.6% reportedly had depression and among those cases the researchers recorded high-levels of kinesio phobia or fears of moving, hence it appeared that the treatment of pain alone in cases with knee osteoarthritis might not be sufficient to reduce fears of movement, and their negative influence on physical activity in the face of untreated depression [41]. Other research of cases with osteoarthritis has shown adults with this condition can exhibit progressive decreases in mental health over time, plus a higher prevalence of chronic conditions relative to age and gender matched controls. They may display greater pain levels as well as reduced physical abilities, a decline in the ability to cope, further depression, and more pain [42].

Increasing research shows moreover, that the failure to apply appropriately timed and targeted interventions that also address depression and its presence as a comorbid and/or reactive aspect of the condition has the potential to adversely influence lower extremity function in adults with knee osteoarthritis [12], as well as upper and lower body functions, even after surgery to alleviate pain [43]. Depression is not only identified as a risk factor for pain, especially persistent pain following joint replacement surgery, but also for its impact on excess health services usage and need, multiple analgesic drug usage, and a reduced overall coping ability, in general regardless of actual pathology and may display less adherence to recommended self-management regimens.

In addition, those in pain may be less active than those deemed pain free and hence less able to control their weight, a key osteoarthritis risk and disabling factor, and one that may lead to higher waist circumference measures and weight adjusted waist index that appears to correlate with depression [44]. Moreover, it appears that those who are depressed and heavier than desired may place excess stress on one or more already damaged joints as well as those not apparently affected. As well, being overweight is a significant determinant of chronic pain in its own right as well as inflammatory responses often found in disabling osteoarthritis. In addition to reduced motivation for physical and social activity, plus self-efficacy for physical activity, persons who are amenable to intervention but overlooked, may incur an increasing sense of perceived failure to adapt to their situations. They may feel less able to cope with their difficulties that may compound their recovery trajectory and reduce their resilience while adding to their poor mental health status even in the face of reconstructive surgery [29,43,45] and especially if suffering from post-traumatic osteoarthritis [29, 43, 46].

Discussion

As outlined above, it is clear preventing or treating depression is likely to be especially important in the context of maximizing the well-being of older adults with osteoarthritis for several reasons. First, they may already be depressed, and hence prone to excess disability as well as more severe disease activity [33]. Second, and in the context of osteoarthritis, a disease frequently associated with obesity and cardiovascular problems including diabetes, related work showed depression can potentially increase the burden of the disease quite significantly in those with one or more of these chronic health conditions. In particular, high body mass indices, often associated independently with depression, can significantly increase the risk for osteoarthritis, while reducing the ability of the individual with osteoarthritis to carry out activities of daily living that affect wellbeing.

Indeed, among a fairly representative sample of studies that have specifically examined the relationship between depression and osteoarthritis, most provide clear support for improved efforts to identify, study and treat this psychosocial factor despite the varied samples studied and differing measures and measurement procedures applied to date, and even if exceeded by problems related to anxiety [29, 43, 45]. Recently, Sergooris et al. [48] reported on two osteoarthritis phenotypes, of which one maladaptive phenotype (34%) reported more comorbidities, less self-efficacy and higher levels of anxiety, depression, pain-related fear-avoidance, and feelings of injustice. No differences were found regarding social support and somatosensory function. Regarding the outcome measures, individuals within the maladaptive phenotype reported higher levels of pain and disability. As well, based on the Fear-Avoidance Components Scale and the anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, individuals could be classified into the clinical phenotypes with 87.8% accuracy.

These aforementioned observations strongly indicate that adults with osteoarthritis may not only be at heightened risk for depression, but that those with depression are more likely to experience more severe forms of the disease than those who are not depressed. The presence of depression, especially if undiagnosed, may also help to explain why the suffering and outcomes experienced by individuals with similar diagnostic forms of osteoarthritis are not uniform. In addition, in contrast to current treatments that commonly focus primarily on the physical and biological domains of osteoarthritis, the aforementioned findings strongly imply that more needs to be done in the context of the psychological realm in efforts to minimize disability and optimize health outcomes. That is, since depression is found to occur among patients with osteoarthritis at rates comparable to those found in other medical conditions, and may prevail in over one fifth of older adults with this condition, more concerted efforts to identify and intervene upon depression where it exists appears highly desirable. From a clinical point of view, this approach could undoubtedly help to avert the presence or magnitude of the unwarranted adverse impacts depression or depressive symptoms may have on an osteoarthritis individual’s wellbeing, as well as their pain and function. On the other hand, older adults with osteoarthritis and concomitant depression who remain untreated are more likely to require high doses of pain-relieving medications, as well as more health services than those with no depression. They may also have fewer social contacts, desire to be more sedentary than not and experience excessively high body mass indices. In addition to pain, the presence of depression has been positively associated with an increased osteoarthritis risk [49] plus activity fatigue, and the overall osteoarthritis disease burden, regardless of age, disease duration, education, or body mass. It is related to increased health care usage, pain-related fears of movement and poor functional status, possible radiological severity and poorer than expected surgical intervention outcomes.

Prevention and management

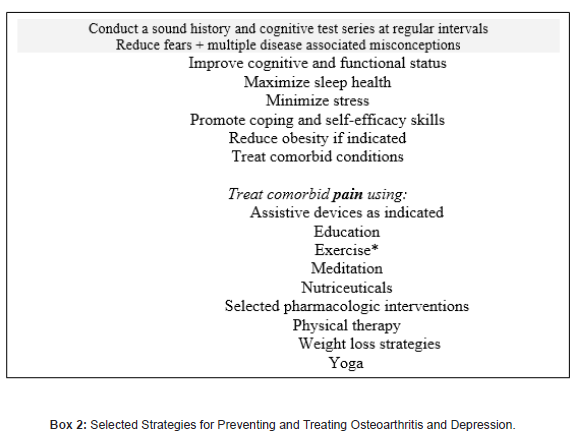

To foster the patient’s desire to remain independent, early rather than late-stage intervention is advocated to limit depressive associations that may prove detrimental to the osteoarthritis suffers, such as pain. In this regard concerted efforts to detect the presence of comorbid depression, followed by appropriate efforts to improve the mental health status of this group are indicated by all who seek to heighten their client’s ability to remain active physically, as well as socially, and to thereby meet their personal life affirming goals, as well as their weight goals more readily. As outlined by several authors, attempts to both minimize osteoarthritis disability directly, as well as to prevent or treat concomitant depression are likely to have far reaching meaningful long lasting beneficial effects. Moreover, dealing with the presence of pain, as well as depression, rather than failing to identify and treat this latter problem, can potentially offset excess functional disability, minimize the extent of perceived pain, reduce fears and heighten confidence to cope with pain, and heighten activity participation, rather than the avoidance thereof, thus reducing excess health care costs.

To this end, efforts to impact depression directly, including some form of cognitive behavioural therapy, emotional and social support, plus a combination of adequate nutrition, exercise, stress control strategies, weight management, and sleep, plus efforts to minimize inflammation and negative beliefs would all appear helpful. Minimizing the extent of any comorbid condition, plus reducing the risk for cardiovascular disease, insofar as these problems can heighten the risk of depression, plus educating osteoarthritis sufferers about treatment options can potentially help affected individuals to control their pain, and thereby to heighten or optimize their mental function. Finally, reducing the stigma of depression, may be helpful as well. As well, rather than waiting until the adult with osteoarthritis requires surgery, the importance of assessing and treating pain plus any attendant depression among persons seeking clinical care for osteoarthritis is especially indicated in cases with physical comorbidities or a coexisting medical condition who commonly exhibit a high prevalence of psychopathology, in order to minimize the possibility of excess weight gain and excessive hip or knee joint deterioration, although when using antidepressants to treat depression, a possible modifiable osteoarthritis disabling facto, the importance of recognizing, evaluating, and minimizing depression safely without side effects cannot be underestimated in the context of both weight control, as well as pain control and with this possible many functional benefits. In sum, because all forms of depression can influence pain perception as well as the severity of any prevailing health condition, and functional disability quite markedly, strategies to treat or minimize depression are highly indicated [15, 50]. Moreover, one or more approaches shown in Box 2 may not only impact life quality favourably, while reducing the extent of any excess health care utilization by the person with osteoarthritis and signs of being depressed [32], but many disabling signs and attributes shown in Box 1.

Indeed, sufficient evidence points to a key role for both physical as well as cognitive therapies that foster feelings of efficacy and confidence and engage the mental and social capacities of the arthritis sufferer. Educational programs designed to foster an individual’s sense of their power to make small changes and enact opportunities to reduce their pain and foster self-management capacity may similarly heighten the individual osteoarthritis patient’s life quality, especially among those with a family history of psychiatric problems, those with medical conditions, those experiencing prolonged stress, and those with limited social support.

Tailoring these according to age, clinical severity, presence of one or more comorbidities, individual preferences, and mental health status, as well as whether osteoarthritis is due to trauma or not, is especially recommended along with effective screening using an appropriate set of measurement instruments, especially among trauma cases [46]. Although research is progressing, research on joints other than the knee that are affected by osteoarthritis, and samples that represent older adults and non-surgical cases are strongly indicated using agreed upon tools and cut off points and classifications for both depression as well as osteoarthritis sub groupings. Whether AI and ‘long distance remote therapy via electronic mechanisms can capture the emotions of the varied older osteoarthritis case and intervene accordingly should be carefully explored as well.

Conclusion

This brief narrative overview concerning the most common joint disease osteoarthritis and especially devoted to uncovering its depressive associations and possible implications as highlighted predominantly in 2024 shows in addition to examining and treating the physical correlates of osteoarthritis disability it may be highly beneficial to examine and treat the emotional factors and mental health indicators that appear implicated in mediating or moderating the extent of osteoarthritis-related disability. Indeed, even though this topic has been discussed and examined for at least 15 years or more, unfortunately the translation of this information into standard practices has been largely limited. At the same time, no promising remedy has emerged, and the disease prevalence is increasing among the older population at an alarming rate, and is one where depressive affective symptoms appear to be observed at three times the rate among individuals with osteoarthritis than among non-arthritic individuals [12]. Moreover, what we have found although sufficiently alarming may underestimate the problem due to the use of cut-off scores for depressive symptoms that vary, as do survey related item questions, and tools designed to measure depression and that are not backed up by clinically valid indicators or do not discriminate depression from anxiety.

Nonetheless, most prior data as well as current data show that where present, the presence of depressive symptoms have a host of measurable adverse health implications that follow and may persist especially as regards two main symptoms of osteoarthritis, namely pain and disability, and poorer health status [12]. Other research shows cases with osteoarthritis are more likely to be classified as being depressed at higher rates than adults with similar characteristics, but no evidence of osteoarthritis, thus leading us to conclude that some cases of osteoarthritis may yet be amenable to treatment. This may be especially important because adults with both osteoarthritis and depression histories are also more likely to experience greater levels of fatigue than those without depressive symptoms and may thus curtail their activities that would otherwise be emotionally rewarding. Conversely, those who exhibit depressive symptoms and who do receive appropriate treatments and treatment recommendations may experience more optimal feelings of well-being and optimism than those who do not, and may be more rather than less willing to pursue activities deemed beneficial to them over time.

Alternately we conclude, that in addition to its negative impact on conservative management approaches commonly applied to help manage osteoarthritis disability, the failure to identify and treat depression, where it exists - may clearly have an equally deleterious effect on surgical treatments, and their recovery rates. Moreover, if depression remains unrelieved, it appears the individual may continue to experience increasing bouts of excess pain, limited function and stress that can not only lead to weight gain, but also to other adverse health problems, such as bone mass losses. They may also exhibit higher rates of deterioration over time. Moreover, even if surgery is seen as the solution to relieving the osteoarthritis pain, if a patient suffers from depression a failure to identify and treat the mental as well as the physical aspects of the disease in both the early, as well as the later osteoarthritis disease stages, much excess and costly suffering will ensue. In particular, women and the less well-educated adult with alow-income may suffer an excess burden of osteoarthritis disability if they are also chronically depressed.

In the meantime, since the functional limitations experienced by people with end-stage osteoarthritis are likely to be largely due to both physical as well as emotional disturbances and pain that is compounded by feelings of depression, taking great care to help clients disassemble facts from misinformation and negative thoughts, for example, that osteoarthritis is inevitable and irreversible is strongly indicated. It also seems that although not mainstream, cognitive behavioural precepts and applications and dispelling the utility of societal mores that demand stoicism and the belief pain and aging are synonymous would be of substantive benefit to many, as would more routine proactive screening for depression followed by appropriate patient specific treatments that are progressive and build confidence. Uncovering any negative associations or experiences that in turn may reduce an older adult’s motivation for self-management and helping them to strengthen the patient’s tendency to avoid physical and social activities can likely help to offset inevitable declines in muscle strength, joint stability, pain and function self-efficacy, sleep patterns, and optimism.

In practice, multi-pronged interventions that specifically target both pain-related physical as well as psychological risk factors, such as obesity, sleep apnoea, can potentially improve the outcomes of both conservative, as well as specific surgical strategies. Moreover, this approach plus the development of a sound trustworthy provider patient set of affirmative encouraging empathetic communications may greatly improve treatment adherence rates, as well the patient’s outlook, goal setting options and decisionmaking ability, in addition to ones one’s coping capacity, and selfefficacy for managing the disease as well as daily functional abilities. This approach may also help allay anxiety, rather than heighten fears about undertaking recommended activities or rehabilitation directives, thus encouraging a more active, rather than a sedentary lifestyle and better perceived health. Directly targeting depression early on is also strongly indicated to improve quality of life.

However, to determine whether or not patients with osteoarthritis are depressed, given the variety of instruments and measures reported for this purpose in the related literature, more effort to identify the most appropriate instrument for identifying depression in the context of specific forms of osteoarthritis is especially indicated. In the meantime, it is apparent that osteoarthritis, a highly prevalent progressive chronic health condition affecting one or more joints of a high number of older adults is likely to foster various states of wherein depression may influence the disease outcomes quite markedly and adversely. Although this area of research is not as well studied as more tangible disease features such as pain, these appear highly indicated. Addressing the sources of pain, and other related health issues may be especially helpful in fostering a higher likelihood of a favourable intervention response and days of restrictive activity. Those who have longstanding disease histories, plus those cases with severe or chronic pain, and multiple joint problems, as well as those who are indigent, overweight, report high levels of pain severity, stress levels, and fatigue, and diseases disturbances, and have few social contacts and cardiovascular disease should be especially targeted.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Courtie SA, Kouki I, Soliman N, Mathieu S, Sellam J (2024) Osteoarthritis year in review 2024: Epidemiology and therapy. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 32(11): 1397-1404.

- Elhamid YAA, Elazkalany GS, Niazy MH, Afifi AY (2024) Anxiety and depression in primary knee osteoarthritis patients: are they related to clinical features and radiographic changes? Reumatologia 62(6): 421-429.

- Aurelian SM, Oancea C, Aurelian J, Mihalache R, Vlădulescu-Trandafir AI, et al. (2025) Supplementary treatment for alleviating pain and enhancing functional ability in geriatric patients with osteoarthritis. Healthcare (Basel) 13(2): 127.

- Silveira J, Oliveira D, Martins A, Costa L, Neto F, et al. (2024) The association between anxiety and depression symptoms and clinical and pain characteristics in patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis. ARP Rheumatol 3(3): 206-215.

- Pascoe MC, Patten RK, Tacey A, Woessner MN, Bourke M, et al. (2024) Physical activity and depression symptoms in people with osteoarthritis-related pain: a cross-sectional study. PLOS Glob Public Health 4(7): e0003129.

- Liu J, Jin H, Yon DK, Soysal P, Koyanagi A, et al. (2024) Risk factors for depression in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis orthopedics 47(5): e225-e232.

- Yan Z, Yang J, Zhang H, Li Z, Zheng W, Li S, et al. (2024) The effect of depression status on osteoarthritis: A powerful two-step Mendelian randomization study. J Affect Disord 364: 49-56.

- Wang Z, Mao X, Guo Z, Huang H, Che G, et al. (2025) Prevalence and factor associated with depressive symptoms in patients with osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res 189: 112018.

- Esposito E, Lemes IR, Salimei PS, Morelhão PK, Marques LBF, et al. (2024) Chronic musculoskeletal pain is associated with depressive symptoms in community-dwelling older adults independent of physical activity. Exp Aging Res pp: 1-13.

- Lentz TA, George SZ, Manickas-Hill O, Malay MR, O'Donnell J, et al. (2020) What general and pain-associated psychological distress phenotypes exist among patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis? Clin Orthop Relat Res 478(12): 2768-2783.

- Wi D, Park CG, Lee J, Kim E, Kim Y (2025) A network analysis of quality of life among older adults with arthritis. int j older people Nurse 20(1): e70010.

- Schmukler J, Malfait AM, Block JA, Pincus T (2024) 36-40% of routine care patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis screen positive for anxiety, depression, and/or fibromyalgia on a single MDHAQ. ACR Open Rheumatol 6(10): 641-647.

- Merry Del Val B, Shukla SR, Oduoye MO, Nsengiyumva M, Tesfaye T, et al. (2024) Prevalence of mental health disorders in knee osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 86(8): 4705-4713.

- Richey AE, Segovia N, Hastings K, Klemt C, Pun SY (2024) Self-reported preoperative anxiety and depression associated with worse patient-reported outcomes for periacetabular osteotomy and hip arthroscopy surgery. J Hip Preserv Surg 11(4): 251-256.

- Terradas-Monllor M, Rierola-Fochs S, Merchan-Baeza JA, Parés-Martinez C, Font-Jutglà C, et al. (2024) Comparison of pain, functional and psychological trajectories between total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasties: secondary analysis of a 6-month prospective observational study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 145(1): 32.

- Hesseling B, Prinsze N, Jamaludin F, Perry SIB, Eygendaal D, Mathijssen NMC, et al. (2024) Patient-related prognostic factors for function and pain after shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. Syst Rev 13(1): 286.

- Martín-Fuentes AM, Ojeda-Thies C, Campoy-Serón M, Ortega-Romero C, Ramos-Pascua LR, et al. (2024) The influence of socioeconomic status and psychological factors on surgical outcomes of the carpometacarpal osteoarthritis of the thumb. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol S1888-4415(24): 00132-2.

- Motifi Fard M, Jazaiery SM, Ghaderi M, Ravanbod H, Taravati AM, et al. (2024) Predictors and prevalence of persistent pain after total knee arthroplasty in one-year follow-up. Adv Biomed Res 29:13: 59.

- Allders MB, van der List JP, Keijser LCM, Benner JL (2025) Anxiety and depression prior to total knee arthroplasty are associated with worse pain and subjective function: A prospective comparative study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 33(1): 308-318.

- Ten Noever de Brauw GV, Aalders MB, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Zuiderbaan HA, Keijser LCM, Benne, et al. (2024) The mind matters: Psychological factors influence subjective outcomes following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty-A prospective study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 33(1): 239-251.

- Peral Pérez J, Mortensen SR, Lluch Girbés E, Grønne DT, Thorlund JB, et al. (2024) Association between widespread pain and psychosocial factors in people with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of patients from primary care in Denmark. Physiother Theory Pract pp: 1-11.

- Norman SS, Mat S, Kamsan SS, Hamid Md Ali S, et al. (2024) Mediating role of psychological status in the association between resiliency and quality of life among older malaysians living with knee osteoarthritis. Exp Aging Res pp: 1-14.

- Zhao K, Nie L, Zhao J, Dong Y, Jin K, et al. (2025) Association between osteoarthritis and cognitive function: results from the NHANES 2011-2014 and Mendelian randomization study. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis pp: 17:1759720X241304189.

- Kareem YA, Ogualili PN, Alatishe KA, Adesina IO, Ali FA, et al. (2024) Demographic and clinical correlates of depression among older adults with arthritis in Nigeria. S Afr J Psychiatr 30: 2264.

- Sonobe T, Otani K, Sekiguchi M, Otoshi K, Nikaido T, et al. (2024) Influence of knee osteoarthritis severity, knee pain, and depression on physical function: a cross-sectet al. Clin Interv Aging 19: 1653-1662.

- Bowden JL, Hunter DJ, Mills K, Allen K, Bennell K, et al. (2023) The OARSI joint effort initiative: priorities for osteoarthritis management program implementation and research 2024-2028. Osteoarthritis Cartilage Open 5(4): 100408.

- Zhang M, Li H, Li Q, Yang Z, Deng H, et al. (2024) Osteoarthritis with depression: mapping publication status and exploring hotspots. Frontiers in Psychology 15: 1457625.

- Fonseca-Rodrigues D, Rodrigues A, Martins T, Pinto J, Amorim D, et al. (2021) Correlation between pain severity and levels of anxiety and depression in osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 61(1): 53-75.

- Rathbun AM, Shardell MD, Ryan AS, Yau MS, Gallo JJ, et al. (2020) Association between disease progression and depression onset in persons with radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 59(11): 3390-3399.

- Del Val BM, Shukla SR, Oduoye MO, Nsengiyumva M, Tesfaye T, et al. (2024) Prevalence of mental health disorders in knee osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 86(8): 4705-4713.

- Tarasovs M, Skuja S, Svirskis S, Sokolovska L, Vikmanis A, et al. (2024) Interconnected Pathways: Exploring Inflammation, Pain, and cognitive decline in osteoarthritis. Int J Mol Sci 25(22): 11918.

- Feng Q, Weng M, Yang X, Zhang M (2025) Anxiety and depression prevalence and associated factors in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Frontiers in Psychiatry 15: 1483570.

- Dong Y, Cai C, Liu M, Liu L, Zhou F (2024) Improvement and prognosis of anxiety and depression after total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Belg 90(2): 211-216.

- Vela J, Dreyer L, Petersen KK, Arendt-Nielsen L, Duch KS, et al. (2023) Quantitative sensory testing, psychological profiles and clinical pain in patients with psoriatic arthritis and hand osteoarthritis experiencing pain of at least moderate intensity. Eur J Pain 28(2): 310-321.

- Broekman M, Brinkman N, Thomas JE, Doornberg J, Spekenbrink-Spooren A, et al. (2024) Associations of mental, social, and pathophysiological factors with pain intensity and capability in patients with shoulder osteoarthritis prior to shoulder arthroplasty: a Dutch Arthroplasty Register Study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg S1058-27 46(24): 00627-X.

- Mehta R, Hochberg M, Shardell M, Ryan A, Dong Y, et al. (2024) Evaluation of dynamic effects of depressive symptoms on physical function in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 76(5): 673-681.

- Sayre EC, Esdaile JM, Kopec JA, Singer J, Wong H, Th, et al. (2020) Specific manifestations of knee osteoarthritis predict depression and anxiety years in the future: Vancouver Longitudinal Study of Early Knee Osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21(1): 467.

- Zheng S, Tu L, Cicuttini F, Zhu Z, Han W, et al. (2021) Depression in patients with knee osteoarthritis: risk factors and associations with joint symptoms. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22(1): 40.

- Ribeiro IC, Coimbra AMV, Costallat BL, Coimbra IB (2020) Relationship between radiological severity and physical and mental health in elderly individuals with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 22(1): 187.

- Aykut Selçuk M, Karakoyun A (2020) Is There a Relationship Between Kinesiophobia and Physical Activity Level in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis? Pain Med 21(12): 3458-3469.

- Yang W, Ma G, Li J, Guan T, He D, et al. (2025) Anxiety and depression as potential risk factors for limited pain management in patients with elderly knee osteoarthritis: a cross-lagged study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 25(1): 995.

- Tan Yijia B, Goff A, Lang KV, Tham Yen Yu S, et al. (2024) Psychosocial factors in knee osteoarthritis: Scoping review of evidence and future opportunities. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 32(10): 1327-1338.

- Brune D, George SZ, Edwards RR, Moroder P, Scheibel M, et al. (2021) Which patient level factors predict persistent pain after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty? J Orthop Surg Res 19(1): 786.

- Korycka-Bloch R, Balicki P, Guligowska A, Soltysik BK, Kostka T, et al. (2024) Weight-adjusted waist index (wwi)-a promising anthropometric indicator of depressive symptoms in hospitalized older patients. Nutrients 17(1): 68.

- Shadbolt C, Schilling C, Inacio MC, Thuraisingam S, Rele S, et al. (2024) Association Between Pharmacologic Treatment of Depression and Patient-Reported Outcomes Following Total Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 40(1): 53-60.e4.

- Farrokhi S, Gunterstockman BM, Hendershot BD, Russell Esposito E, McCabe CT, et al. (2023) Post-traumatic osteoarthritis, psychological health, and quality of life after lower limb injury in US Service members. Military medicine 189 (7-8): e1805-e1812.

- Ravi A, DeMarco EC, Gebauer S, Poirier MP, Hinyard LJ (2024) Prevalence and predictors of depression in women with osteoarthritis: cross-sectional analysis of nationally representative survey data. In Healthcare 12(5): 502.

- Sergooris A, Verbrugghe J, Bonnechère B, Klaps S, Matheve T, et al. (2024) Beyond the Hip: Clinical phenotypes of hip osteoarthritis across the biopsychosocial spectrum. J Clin Med 13(22): 6824.

- Ogunsola AS, Hlas AC, Marinier MC, Elkins J (2024) The Predictors of osteoarthritis among U.S. Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005 to 2018. Cureus 16(6): e63469.

- Mulrooney E, Neogi T, Dagfinrud H, Hammer Hb, Pettersen Ps, et al. (2023) Comorbidities in people with hand oa and their associations with pain severity and sensitization: data from The Longitudinal Nor-Hand Study. Osteoarthr Cartil Open 5(3): 100367.

-

Ray Marks*.Review of Osteoarthritis Depressive Associations 2024-2025 and Their Implications. Glob J Aging Geriatr Res. 3(4): 2025. GJAGR. MS.ID.000569.

-

Osteoarthritis, Health Challenges, Knee Surgery, Depression, Aging Adults, Therapy

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.