Research Article

Research Article

Harm To the Sense of Self from Deference Obligations in Aging Services

Sonia Salari*

Department of Family and Consumer Studies University of Utah and Fellow, Gerontology Society of America, USA

Sonia Salari, Department of Family and Consumer Studies University of Utah and Fellow, Gerontology Society of America, USA.

Received Date:January 13, 2023; Published Date:February 03, 2023

Abstract

The aging of the population in pandemic times will require a redefinition of services to accommodate the public health, physical and psychological needs of older adults. When institutional goals supersede the individual, adults lose status from inappropriate environments and behavior. Data from 420 hours of observations and 74 insider interviews from 10 formal settings (2 residence, 5 adult day and 3 multi-purpose senior centers) were collected and analyzed over several years. A salient theme emerged where rigid rules in institutional settings exposed clients to reprimands and punishments, as they internalized the need to ‘behave.’ Voluntary organization ‘joiners’ had little need for deference, particularly in self-governed environments. Observations documented assertive inquiry among those who retained a strong sense of self. In addition to safe activities and prevention of virus transmission, aging services have an ethical obligation to provide consumer-driven opportunities, allow maintenance of adult status, autonomy and self-continuity.

Keywords:Senior centers; Adult day centers; Person-centered care

Introduction

Under normal circumstances there has been a worldwide increase in the elder adult population. In the United States, with the aging of the baby boom cohort, those 65 and over were expected to more than double in the years between 2010 (40.3 million, 13% of population) and 2050 (83.7 million, 20.9%) [1,2]. Considering this expected growth projection of the elder adult population, the COVID-19 pandemic created excess deaths, particularly among those with advanced age or pre-existing conditions [3]. Aging services were heavily influenced by the spread of the disease, closures, stay-at-home orders and the need to social distance [4]. This pause has led to a great deal of hardship for older Americans, their caregivers and families. There is also evidence of increased isolation and vulnerability to elder mistreatment [4-9]. The virus laid bare the decades of abuse and neglect which had been occurring in long-term-care, which was catastrophic once the pandemic hit [9-11]. This manuscript builds on the infantilization literature and encourages the opportunity to redesign and retrain as we reopen the aging services and facilities as we move beyond the acute pandemic era (prior to vaccine development). An improved future will need to be ‘reset’ by avoiding pitfalls and employing best practices for retention or promotion of identity, autonomy, selfdetermination, and adult status for persons of all cognitive abilities.

How will aging services, residence facilities and voluntary organizations accommodate the demand and adapt to the personal and social needs of older adults beyond the acute pandemic era? There are likely to be more intense conditions of acute staffing shortages and hesitance among elder adults to risk exposure in formal settings. Historically, care environments have focused attention on institutional goals, with an emphasis on efficiency to conduct tasks for the masses on a schedule [12,13]. The unintended consequence of this process has been a disregard for the adult status and the personal preferences of consumers [14-19]. Some evidence suggests voluntary aging services such as senior centers have been declining in attendance in recent decades [20-22] and will need to adapt to the desires of the baby boom cohort to remain relevant [23,24]. Even before the disruption of the pandemic, some aging services were in ‘survival mode’ desperately attempting to draw in younger seniors. What are the ethical obligations for a good psychological atmosphere to accompany opportunities for social interaction and healthcare? How can aging services strive for the familiar comforts and freedoms of adulthood, for those with all levels of cognitive or functional capabilities? Person-centered cultural changes cater to preferences regarding daily schedules, food, privacy regulations, outdoor recreational opportunities, and meaningful activities. These represent a heavier burden for institutions, and such shifts require a dedicated push to turn best practices ideology into reality. The outcome is expected to improve quality of life (QOL) for clientele with or without cognitive disabilities [25], as institutional pressures of mass conformity are overridden [26,27].

Optimal aging allows the freedom to continue our lifelong selfdevelopment, even with mental or physical challenges [25]. Selfhood involves ‘fulfillment of needs for competence, relatedness and autonomy (p. 255),” and self-continuity follows these perceptions over time, from the past to the present, and into the future [28].

Infantilization subjects’ elders and those with disabilities to child-oriented speech, behavior and environments, which can threaten the individual’s sense of self and adult social status. This problematic atmosphere permeates a variety of care settings [29,30] and trauma may be experienced as one transitions from independence to becoming reliant on a service environment. The new role may lack the choice (autonomy), meaningful activities and privacy regulation usually experienced and taken for granted in normal adulthood. This manuscript draws on data from an observational study of 10-service settings (over 420 hours), which included 74 insider interviews. Emergent themes indicated the existence of authoritarian rules, harsh enforcement, deference obligations and the struggle for maintenance of personhood among consumers. Self-preservation was possible to varying degrees and under certain circumstances.

Theoretical Background

The self-concept is shaped, in part, by influences based on others’ point of view of us, particularly if they hold a position of importance. Cooley’s looking glass self indicates we might adopt the real or imagined judgements, such as feelings of guilt or inadequacy, and respond with a petition for approval. This shows how others may influence our personalities and disrupt our equilibrium--even if temporarily or superficially [31,32]. Built on this work, arguing that modern adults monitor the self in relation to others, which influences behavior. Humans create their social lives around a fear of public shaming, based on a complex system of informal sanctions that regularly encourage conformity.

Merton’s [33] notion of self-fulfilling prophecy revolved around a false definition or prediction, which creates a new behavior, rendering the original judgement true. Child development has adopted this perspective to warn of the dangers of labeling. Gerontological research used this concept to explain the finding of subjects in mid and later life who held ageist views performed worse on memory tests, compared to controls [34]. Psychological mistreatment among elder adults is rarely reported to authorities, but represents a rather common and persistent problem, and is expected to increase as the population ages [35-37] defined psychological abuse as “the infliction of mental anguish, e.g., treated as a child...humiliated, intimidated, threatened or isolated.” These forms of abuse in later life can undermine self-confidence and even encourage dependency [38,39]. Persons using services designed to accommodate disabilities may adopt the cultural cues from the staff and environment, in a self-fulfilling prophecy. If the cues are infantilizing, this process runs counter to healthy adult development [18]. In contrast, least restrictive environments [40,41], with adult levels of autonomy, privacy regulation, productive activities and choice, allow service users to better maintain adult status [16-18].

Some have argued our surroundings also play a role in shaping our sense of self [42] in aging environments [43] and services [44-46]. When the physical setting does not fit the individual’s competencies, it can create discomfort or ‘press’ and lead to maladaptive behaviors [43]. Environments can have place rules [47], which can be explicit (no breakfast served after 7:30 am) or implicit (sleepers discouraged during mandatory activities). The perspective of looking-glass self could include the social and physical setting as a source of judgement on an individual. Subordination requirements by a service provider may cause insiders to internalize feelings of inferiority. In previous adult day center research, evidence suggested the freedom to interact and form friendships was hampered by infantilized settings. Resentment was expressed by several consumers who were subjected to childoriented games and decor, mandatory activities, baby-talk (i.e., high pitched, slow, exaggerated intonation, etc.) and nicknames [16-18]. Gerontologists have perceived this as mistreatment [48] and view those with functional and/or cognitive impairments as particularly vulnerable.

Goffman’s [49] work described infractions to the rules of conduct in public and private spaces. Formal deference obligations exist toward others as well as expectations of how others will react. Social situations typically require individuals to communicate deference to authority and adjust demeanor (presentation of self). Failure to observe the rules of conduct (rule breaking) can lead to shame and humiliation. Conveyance of deference can be symmetrical (mutual, among peers) or asymmetrical (one directional, toward a person of authority-but not vice versa).

Subordinates may be subjected to treatment which does not obey social rituals, such as intrusions to the boundaries of personal space (privacy regulation), name use, talk about client in his/her presence, surrender of possessions, forced food or medications, etc. In theory, one’s demeanor projects an image and hides unfavorable personal attributes from public scrutiny. However, control over demeanor is difficult under constant monitoring. Regular bathing may improve demeanor, but also shows deference to those nearby. An environment may make it difficult or easy to be a person, “it depends in part on the type of patient…and the type of regime the staff attempts to maintain. [49].” Negative deference (hostile outbursts) are reflections of contempt for the institutional rules of conduct and may reflect either 1) impulses from organic brain disease or 2) symbolic meaning related to resistance, but these are not mutually exclusive. Self-determination is key, to allow a person to show proper demeanor and deference in ongoing communication with others. A person restrained to a bed can neither retain positive demeanor nor show proper deference—this reduces the penalties for serious behavior, such as soiling oneself. By constricting environments and movements, the “ceremonial grounds of selfhood can be taken away… [there are] conditions that must be satisfied if individuals are to have selves [49].”

Goffman’s [12] study of mental patients in an asylum (“total institution”) examined the most serious offenders of the rules of conduct in society. He illustrated the processes whereby individuals respond to pressures of “self-mortification,” where they are stereotyped as incompetent and stripped of their identity. In this condition, they were required to ask or bargain for the most basic requests, such as a drink of water. To resist deference obligations is to be labeled as a troublemaker. Marson and Powell [29] applied Goffman’s perspectives on social interaction to the existence of infantilization “scripts” in the care of older persons. They suggest the targets of these child-oriented interactions may adopt a more reserved demeanor, resulting in further isolation and feelings of incompetence, which may be reversible with staff training.

These issues continue in modern day caregiving relationships where those with less power are expected to show deference to the powerful, to prevent strain in caregiving relationships. Deference obligations may reflect a self-fulfilling prophecy where service users adopt the child status assigned to them. Bowing to the interests of more powerful entities (staff, caregivers), subordinates adopt status assigned to avoid conflict, rather than lose face in a confrontation [50].

Tom Kitwood’s work promoted recognition of the subjective experiences among those with cognitive impairment. Namely, negative treatment could create interpretations and reactions among those with dementia, and their perspectives are worthy of consideration [25,51]. In his book, Dementia Reconsidered: The person comes first, Kitwood envisioned an isolated world shaped by dementia which had become chaotic and cold:

As soon as people with dementia are seen as merely “behaving” (having meaningless movements or verbalizations) an essential feature of their personhood is lost (p. 87)... Prevalent and insidious...there are subtle ways of demeaning and discounting the person… incorporated into ordinary interaction: tiny remarks tinged with mockery or cruelty; exercises of social power; subtle manipulations; insinuations the other is inadequate; avoidances of direct emotional contact [25].

Isolation surrounds the person with dementia with a malignant social psychology which dehumanizes and invalidates the personhood of the individual and may even accelerate the course of neuro-pathological processes [52]. Ultimately the target of this behavior will become defensive and wary of others and will learn to stifle his or her social expression. As an alternative, positive social development and interaction can encourage humane care where those with disabilities can have the confidence to “live their lives as social beings [51],” with a long-standing personality, style and life story. Rather than blame caregivers, the goal is to encourage a conscious effort to include humane socialization and treatment options to promote the maintenance of personhood over time. The introduction of the person-centered culture with a focus on the least restrictive environment for services and long-term care, has been important, even for those with dementia.

Institutions (Total and Partial) and Community-based Aging Services

This manuscript contributes evidence collected over the course of a gerontological career from a multitude of observed settings. Residence facilities are restrictive environments (total institutions) because social interactions take place in the same environment, under the same rules and authority day after day. However, settings can vary in the interactive culture, environments and behaviors [30]. Validated tools have been used to evaluate person-centered facilities, but the hard evidence of improved quality of life is elusive [53].

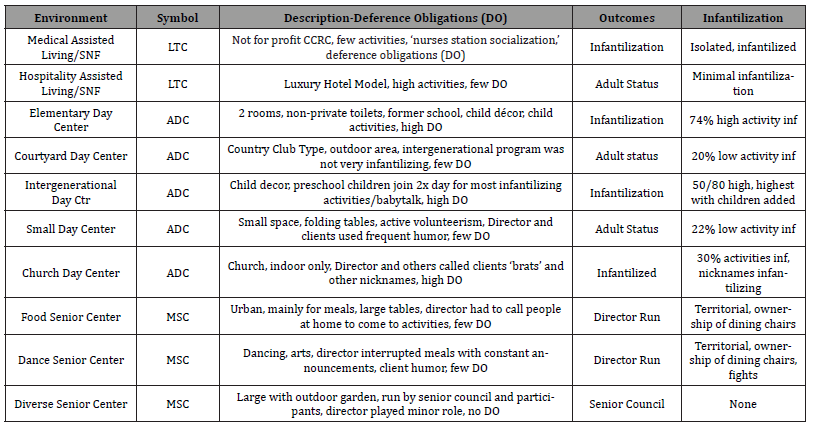

The term partial institutions [19] was first utilized to describe adult day centers where clients with functional or cognitive impairment were only confined on a part-time basis. After hours, they retreated to a private home life where restoration of the psychological and emotional balance may have been possible. Positive effects of adult day service have been observed to lower stress on family caregivers who reported better sleep and fewer behavioral problems among persons with dementia after using adult day services [54]. The 5 adult day centers (ADC) observed in this research were found to have varying levels of mistreatment in the form of infantilization. High levels of child-oriented treatment led to adaptations by clients, such as “challenge” behavior (sometimes aggressive, lack of cooperation) or “withdrawal” (sleeping, low participation) [18]. For example, two women in a facility (Intergenerational ADC) described anticipatory withdrawal, where they planned ahead and moved to the back of the room to avoid the visiting children and baby-talk activities. Maintenance of adult status was possible as they had conversations together to resist the negative effects of infantilization Table 1 [30].

Table 1:Ten Aging Service Environments: Descriptions, Deference Obligations and Infantilization.

Multi-purpose senior centers (MSC) are voluntary organizations commonly utilized by “joiners,” who can come and go freely. Therefore, these organizations compete for members and are not in a position to require deference toward authority. The three MSC in this study had very little infantilized behavior toward users, but there were differences in the director’s use of power. Specifically, territoriality and conflicts over dining chairs existed among participants in two of the centers (Food and Dance MSC), with low levels of control among participants. Diverse MSC exhibited no infantilization or territoriality because the director relinquished authority of the schedule and activities over to users, the results found positive reactions [18].

This manuscript concentrates on the themes which emerged surrounding place rules, deference obligations and the maintenance of personhood in 10 environments for elder adults. Readers will become familiar with the hallmarks of institutional goals, adherence to rigid rules and the behavioral options and consequences for the sense of self among those targeted to comply. And finally, distinctions in aging environments will indicate the how some avoided strict place rules and deference requirements, for a more consumer driven option.

Methods

Qualitative inquiry is recommended for optimal study of environments aimed to serve the elderly population [13,18] and to help bridge the gap between knowledge and practice [55]. This study represents a comparative ethnography of 10 aging service cultures, including 5 adult day centers (ADC, 220 hours; 24 interviews), 2 residence long term care facilities (assisted living and skilled nursing) (LTC, 80 hours; 20 interviews), and 3 multipurpose senior centers (MSC, 120 hours; 30 interviews). Each setting was observed for at least 40 hours, and ours was among the first to include insiders’ perspectives regarding their role, the activities, staff and service setting. Human subjects’ approval was obtained from both the university IRB and state area agencies on aging (for the multipurpose senior centers). In the case of LTC and ADC, both informant and family member consent were obtained. The sample size was constrained in some rare cases, when family members opted out. Removal of identifying information meant site locations were omitted, and client/staff names were replaced by pseudonyms. A research statement was read out loud and posted publically for the duration of the study. Trained observers in each setting employed minimally obtrusive techniques and took field notes for detailed recollection. A “busywork” technique prevented eye contact with staff to discourage conversations or recruitment for tasks, etc. Our team of researchers were not participant observers.

Observation field notes were transcribed on-site or soon after each session. Similarly, we conducted formal interviews across service categories. These data came from a career-long span of time over multiple settings. Elementary ADC was part of a pilot study conducted in 1989 and had only one interview. The remaining conducted between 1996 and 2002, included a purposive sample of men and women interviewed to a point of ‘data saturation’ (new information was unlikely from additional interviews). Dementia did not exclude a participant, as long as there was some lucidity and conversational ability. The interview questionnaire included semistructured and open-ended questions about quality of life (QOL), friendships, conversations, activity choices, the environment and interactions with staff members. Interviews were conducted in a private area for about 45 minutes to 1-hour. Audiotapes were transcribed with identifiers removed. Weekly research team meetings discussed field notes and interview transcripts. Grounded theory was utilized with a reiterative process [55,56] of data analysis focused on recognition of service culture, coding of concepts and the emergence of themes which were confirmed by inter-rater agreement. Selection of quotes from observations and interviews are evidence of these research products.

Results

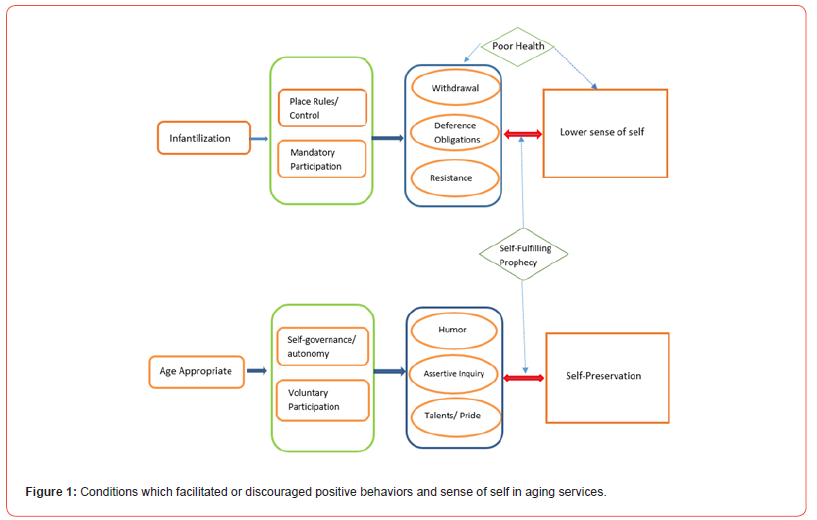

The model illustrated in Figure 1 represents a guide to the results. Infantilized settings had rigid rules and institutional control, as well as harsh enforcement of mandatory activities. Client responses were to withdrawal, show deference to authority or resist (aggressive or challenge behavior). Losses to the sense of identity or sense of self among clientele were evident from the quotes reported. Poor cognitive or physical health could be a contributor to some of these outcomes. The double-sided arrows represent self-fulfilling prophecy. The reactions to rigid rules led to a loss of identity/self, and caused further withdrawal, deference and resistance. Age-appropriate settings allowed for the maintenance of autonomy and choice regarding attendance and participation in activities. Confidence was evident as participants often approached the researcher with assertive inquiries as to his/her purpose. They also conveyed a strong sense of humor and happiness, with frequent laughter. Pride was another attribute, as they were able to show off talents or describe their own higher education achievements. Selfpreservation was a result, and this in turn reinforced the positive reactions noted in step 3 Figure 1.

Residential Facilities

The Medical LTC (long term care) model residence facility had a positive reputation in the community, due in part to housing provided with charitable standards of payment (religious affiliation). Observations found structural conditions resulted in lack of meaningful activities for residents. The Activity Director’s office was located behind the scenes, inaccessible to residents. The schedule of events was often cancelled (with or without official notice). One observation had a tape-recorded message, with no live facilitator. Music programs were held with visiting performers, who used baby-talk, nicknames (babies, etc.) and referred to residents as “cute.” A nurse was observed to ask residents “Are you behaving yourself?” One replied, “No not really.”

Without frequent formal activities, there were long periods

when as many as 10 residents hung out in the hallway near where

staff were located. This nurse’s station socialization [30] was not

fulfilling and often met with verbal expressions of dissatisfaction.

Nurses were observed to ignore or avoid these residents. One

suggested the researcher move away from Ms. T because she “will

bug you the whole time.” Later, in front of residents, the head nurse

explained what she considered problematic behavior:

Head Nurse: It’s called sun-downing. It brings out their

bitchiness, shortness with each other. Watch Ms. T. People don’t

change. She has been catered to her whole life, so now she’s real

demanding.

Male Nurse: They get like little babies, they wake up and cry

(rubbed eyes), eat, play and take naps.

Head Nurse They are like 2-year-olds. But don’t treat them like

that. If they don’t get the attention they are used to, they fuss

until they do. Yesterday was crazy.

Negative reputations were publicly discussed in front of the

observing researcher, other nurses and the residents. So-called,

“bad” behavior often revolved around staff control. The head nurse

described her need for organization, with a priority plan. Resident

behaviors outside of these institutional goals were ignored or

met with staff resistance. A new resident, Ms. C, was a friend of

observing researcher’s mother. She attempted to approach but

was confronted by a nurse “Sit down in the chair.” Ms. C became

defensive and almost pushed the nurse who stood in her way.

Her voice was stern “Stop telling me what to do!” This assertive

confrontation of authority was not at all common among the other

long-term residents. They gathered at the nurse’s station, but often

nodded off to sleep in their chairs. Occasionally they would make a

comment, which was left without follow-up or criticized by nurses.

Ms A appeared on scene and seemed confused. She attempted to

engage the staff, but was unsuccessful, so she asked the researcher

“Am I on the right floor?” She asked the aide “You’ll let me stay? I

behaved?” On a later occasion, others reflected similar sentiment to

the researcher as they filed past her to leave the dining room.

Ms. V Did we pass muster?

Ms. R Have we behaved ourselves?

Ms. S: What are you writing about? Are we behaving ourselves?

I had a hard time when I came…I could have gone out and killed

myself the first day. One day you are taking care of yourself

and the next…you’re nothing. You’re just existing and you’re

nothing. It is really hard… I have gotten kind of used to it, but

I haven’t accepted it at all. I know, you can call your paper ‘the

last stomping grounds.’ Write something good about us.

Asking if we ‘behaved’ and describing the perceived drop in status with institutionalization –the negative process of becoming “nothing” indicated a perceived loss of self. Independence was also lost in the Medical LTC. Ramps constructed between new and old building construction meant that staff had to help people with mobility limitations get from point A to point B. Interviews confirmed instances where residents ate in their rooms, due to an environment considered too difficult to negotiate.

Rather than relying on sterile medical hallways, the Hospitality LTC model floorplan resembled décor in a luxury hotel. While some struggled with assistive devices through the tight dining table arrangements, few other physical barriers stood in the way of mobility. The resident-staff interactions were observed to be more age appropriate than Medical LTC. Formal organized social interaction was encouraged, as two activity directors had offices visible and available to residents (one per floor). Activity programs were publicized and carried out as scheduled. Most interviews indicated positive aspects of Hospitality LTC, but Ms. J felt “out of my life,” from the effects of institutionalization. She perked up to describe the happy hour program with alcohol.

Ms. J: “You get one glass and a second. If you were a good girl, you get a second (laughs). Not very good wine…but…people are quite conversational…makes them feel a little lifted up.”

She seemed to have internalized the requirement of abiding by the rules during the activity, along with referring to behavior requirements to be a ‘good girl.’

Another interview Mr. P reported Scottish ancestry and a recent stroke last year. After the health crisis, he described a period of self-imposed isolation, including eating meals in his room. His conversation centered around concerns about his adult son, who intervened on his behalf.

Mr. P: My son, I can’t believe him… He seems to think he is the father (laugh). He’s got this little kid to take care of…I tell him something up here I don’t like…geez…The next thing I know, it is all straightened out…He’ll go right to the Administrator… Don’t rub him the wrong way.

This behavior resulted in feelings of loss of control over his own affairs. During observations, we noted a staff member kept Mr. P thinking positively, asking him if he was “still a celebrity” (referring to a television news interview he did about a presidential speech). His answer gained energy.

Mr. P “A woman asked me if I wanted to answer a few questions… there were all these cameras, lights and the next thing you know they were attaching a microphone to my shirt. I just can’t get over it…He is the most…powerful man on earth, and they want my opinion on the speech…I get to bragging and I feel good. It brings me back to normal. I have a father-son relationship with my son. He is the father, and I am now the son. This [interview] brings me back to normal again. I’m lively and I feel good.”

Local fame allowed Mr. P to feel self-assured and independent as an adult, in relation to his health, the institution and his son.

Another man in the Hospitality LTC preserved his sense of importance with a narrative.

Mr. L: The guy that I bunk with…we are businessmen…we like doing our own thing…But this place, they recently got a supervisor guy who…looks after everything people do here… But I’m silent. I’m a maverick…One of the [staff]…makes a regular thing out of whether I change my clothes every day or not…it just drives me crazy…People...who give us showers…are good people and they try to be reasonable, but sometimes they really get carried away and say ‘You’ve got to do this, you’ve got to do that.’ And I don’t go for that… When I pay my bill… They…put themselves financially in charge of me and I hate it…I have my own bank account and I pay my own bills, and I’m as independent as they ever came. I believe it is how the supervisors like it. They don’t want me to be responsible for anything…[Later] If I’m not doing it the way they want, they’ll speak out and I’ll speak right back…he’s not gonna yell at me… That is why they call me maverick.”

When asked about other residents and staff treatment, he

responded:

Mr. L: About 50% of them [residents] are …limited…And they

try to talk to me like I’m one of the limited ones. I say, no I’m a

businessman… [It makes me] feel like a has-been…I sometimes

tell them a little bluntly that I’m not a stupid idiot...and I like to

do things.”

To Mr. L, defining himself as a businessman conveyed a measure of professionalism to counter the notion that his hygiene and finances should be controlled by the facility.

Adult Day Centers

Partial institutions had deference obligations related to the degree of infantilization in the settings. Two centers had the highest levels of infantilized activities Elementary ADC (74%) and Intergenerational ADC (50%). In addition, there were childoriented environments, the use of baby-talk, central mandatory activities (with no escape options), nicknames, and a lack of autonomy. Church ADC had a moderate level of infantilized activities (30%), but the overall atmosphere was extremely childoriented, with frequent use of personal derogatory nicknames and harsh reprimands (mostly from the management). Two other centers (Small and Courtyard ADC) had a minority of activities deemed infantilizing (20-22%). These two settings were most likely to provide age-appropriate speech, behavior, environments and activities (See Salari, 2006) and had the fewest signs of deference obligations in the adult day centers studied.

To begin with the most infantilized partial institution setting, Elementary ADC environment was located in a former school classroom, with few attempts to upgrade the décor [19]. Acute infantilization was related to the lack of privacy regulation and having clients spoken about, as if they were absent. The medical conditions of participants were regularly described in front of the group as if they were not in the room.

Director: Some are high functioning, and others are not. For example, W. We don’t really know what he knows. He doesn’t have Alzheimer’s…. He was in a construction accident, and a girder fell on his head. He suffered brain damage…. Some days he seems to know what is going on in the news...

Mr. W ‘checked out’ of central mandatory activities by sleeping in his chair. Unfortunately, in observations he was repeatedly woken abruptly by staff. His response was sometimes aggressive. Given there were child-oriented, central mandatory activities, others were woken in similar fashion. Free movement outside of staff plan was discouraged. On several occasions Mr. ML attempted to approach the researcher to talk about his family member’s graduate work. He was typically intercepted by the staff who asked if he needed a tissue or to use the restroom.

Toileting rituals exposed clients to public scrutiny, as their bathroom stalls were located between the two former classrooms. Rather than being discrete, staff members made loud, humiliating comments while clients were toileting [18,19]. Whenever someone in the center stood up, it was usually assumed they needed to use the restroom. Mr. P stood up and female Staff W asked, “Do you need any help?” He replied to no. She remained and said, “I will stand here and help.” Similar treatment was provided to Mr. M because of his reputation for having “vulgar habits,” which were described out loud by Staff H. Our observational notes indicated none of these habits ever took place during our study.

The need to ‘behave’ was conveyed during staff-client conversations, such as a discussion of a party attended by two clients. After Ms. Mar described a child’s birthday party attended by Mr. J, Staff K asked, “Did Jim behave himself at the party?” Staff B chimed in “He was a good boy.” Ms. D then responded to the questioning and said she didn’t do much over the weekend. She added “I behaved myself.”

During his interview, Mr. T commented on the low levels of education and limited cognition among other clients and suggested “I’m better off than the people who run this place... Some (mean face) errrr! That one woman, J, doesn’t like me, I said something to her, and she snapped at me.” Although he reported he gets along with most people, he had a distinct lack of interest in attending the Elementary ADC, because “the things they do are just like children’s things…I would rather be someplace else.”

Intergenerational ADC had good intentions by combining

generations, but the pre-school children were treated as status

equals and brought into the room twice daily. These practices

made adult status difficult to maintain [16]. Joint activities were

characterized by baby-talk aimed at both generations. A game

where children searched for a penny in the hand of a “grandma

or grandpa” resulted in high-pitched commentary “Hold your

hands like this honey, that’s a good girl.” Worse were the frequent

reprimands observed. Two clients (Ms. R and Mr. B) tapped other’s

leg during exercise class. Without warning, they were separated as

punishment. After the reprimand, Mr. B slept, and Ms. R frowned

and ceased any further participation. Later that day, Ms. R was

again reprimanded as she requested a snack. Staff 1 said “Just BEHAVE

R!” she replied, “I’m trying to, just leave me alone.” All day,

child-oriented labels, judgements, and physical isolation in “time

out” were observed. A memory exercise focused on trouble:

Staff 5: What’s your hiding place Ms. RU?

Ms. RU: I didn’t hide any place.

Staff 4: Where you a good girl that you didn’t have to hide? (Ms.

RU didn’t answer)

Staff 5: Mr. H, what places did you get stuck in? (He didn’t

respond)

Ms. RU: He got stuck in a girl! (She received hard looks from

staff)

Later, after the trivia exercise was over, Staff 1 said “I’m done.”

And Ms. RU yelled “Good!” The following observation repeated

a code word for ‘troublemaker’ and showed client adoption.

Staff 4: She is being very ornery.

Ms. RU: I am ornery today.

Staff 4: She even admits she is ornery!

Later…

Staff 5: How are you Mr. A?

Mr. A: Mean and ornery.

Staff 4: Are you being ornery today?

Mr. A: Yes, I am.

Clients were split into groups –Ms. RU was assigned to work

on a puzzle, against her will. So, she stared at Staff 2 and moved

some of the puzzle pieces around. Staff 2 said “Ms. RU you are just

determined not to participate in the puzzle game.” Irritated, Staff 2

relocated RU’s wheelchair to the middle of the kitchen with the lock

on. After 2-minutes she was asked if she wanted to rejoin the group.

She said no. Eventually she changed her mind but maintained she

does not like puzzles.

Staff 2: What would you like to do?

Ms. RU: Just sit here. (She flicked the puzzle pieces)

Staff 2: Come on Ms. RU we are leaving. You’re not being nice.

Her wheelchair was returned to the kitchen, where she attempted to stand up in protest. Ms. RU tried to signal Mr. A and whispered to him “Staff 2 is mean.” Staff 2 repeated “She is ornery today.” During this observation Ms. RU attempted to stand and staff agreed she might fall.

‘Ornery’ and other words like “grumpy” were adopted to refer to themselves. Staff 2’s strategy to control Ms. RU isolated her, against her will, but she was defiant when asked if she would like to return (major deference obligations, denied). There were no alternative activities offered. Ultimately, Ms. RU was required to show deference to rejoin the group. By asserting her preferences, she was considered a troublemaker. Staff 2 predicted the researcher would have many notes, since Ms. RU was “ornery…and being so bad.” Similar control tactics were utilized as they colored Father’s Day ties in a subsequent observation. Ms. L swore in frustration when she couldn’t successfully replace the lids on her markers. Staff 5 said “There is no swearing in here, we will put the markers away if you can’t behave.” The situation escalated and she attempted to get up out of her seat, but the staff asked her to sit back down. She swore again. Staff 5 placed her hands on Ms. L’s shoulders and said, “If you don’t stop cussing, I will have to put you in time out.”

In another incident, Ms. P shouted at Ms. R for swearing during an activity. In a reflection of the culture, she demanded Ms. R be placed separately from the group. Staff asserted authority by separating both women from the group. Deference requirements seemed to be contagious, turning clients against one another, relying on punishments to isolate the offender.

Mr. X was pre-emptively warned early in the day “You better be good today or you can’t stay here…We only like people that are good in here.” The researcher heard staff refer to his negative reputation, but no examples were observed to warrant this action. Observations noted food rewards were also denied for “being bad today” or provided “for being a good boy.”

Similar to Elementary ADC, non-participation in central

mandatory activities was a source of reprimands. Ms. L dozed

off to sleep, when she was awoken to participate. She reacted by

sticking out her tongue at Staff 2. The response required deference

obligations.

Staff 2: You need to start behaving like an adult, you’re not going

home now so you need to start behaving.

The activity to make cow puppets from small paper bags was conducted in baby-talk. Ms. M opted out and stood by the window to wait for her ride. She was mocked by Staff F “She’s acting like a little kid, when their parents are picking them up. Are you a grown kid?” Ms. M acquiesced by saying “yes.” Opting out of a childoriented activity was criticized by staff, but she knew her time there was temporary, and escape was inevitable.

In the Church ADC the director conducted central mandatory

activities, which were often child oriented. For example, asking

clients to spell their own name. Mr. W objected to the game. Director

“Oh spell it you brat!” and she skipped his turn as punishment.

Participants were under stress to defer to this authority. Staff

regularly used ‘reality’ exercises to spur past memories.

Staff 1: L, did you ever get in trouble? (Client responded no) …

(to Mr. S) I heard you got in a fight; did you ever get in trouble?

(He said no) …Did anyone ever play hooky?

Later that day

Director: Who got in trouble at school?

Mr. D: I have, oh yes. …

Director: You mean the rest of you didn’t get in trouble?

Ms. F: I was scared of my parents...

Director: Has anyone ever had a bully in their life?

Another day

Director: Why don’t you come sit over here C

Ms. C: I like this rocking chair.

Director: Well, we try to keep everybody together …What kind

of mom did you have?

Ms. D: My mother was a real pain…and she was always telling

me what to do.

Director: Who had siblings? Did they beat up on you? Did you

ever talk back to your mom?

These punishment themes keep clients stuck in a child-oriented state of mind, along with the fears of being “in trouble” or punished. Interestingly, their responses found a way to object to being told what to do. Ms. A yelled out loud “We’d better be good!”

On a daily basis there were additional inappropriate comments made in front of clients. A staff member described why safety measures were needed around visiting children.

Staff 2: If you had an older person with a walker and you knocked them down, they’ll break a hip. Then you might as well shoot them.

This comment reduced the human value of the entire group down to a burden to be euthanized. Given the reprimand atmosphere, punishment was a concern reflected in Ms. C’s interview as she internalized the cues and attempted to stay out of trouble and make the best of the situation.

Ms. C: As long as I don’t get in trouble. I love it here, they are very good to me and I behave myself… Are you sure you won’t get me in trouble?... That is the one thing I don’t like is trouble…I don’t give [staff] any trouble. They don’t complain about me, because I don’t bother anybody…Now, are you sure this isn’t going to get me in trouble?

An age-appropriate visiting movement therapist VMT brought the participants in Church ADC to a different level, as she was age appropriate and encouraged song requests. Resistant at first, and fearing humiliation, Ms. L. said, “I don’t want to pick a song because they will all shame me.” Later she agreed “that was really, really nice” Ms. T added “We need to do some more of that song.” On another day Ms. A said “You have really livened up this crowd, you give us new life…VMT responded “I think we give each other life.” In 40 hours of observation, she was the only facilitator who received positive client feedback. Afterward, participants seemed relaxed, and humor surfaced as they played mini putt and Ms. F joked about being married to Tiger Woods, “I could relieve him of some of his money!” Staff and clients laughed and played along as they referred to her as Tiger Wood’s Wife when it was her turn to putt.

The other two adult day centers (Small and Courtyard ADC) were more adult oriented and had fewer central mandatory activities. Both had visits from visiting movement therapist VMT about 6 times per month. Courtyard ADC had 68 people on the books, but we saw between 30 and 41 attend at one time. The property was relatively large, and the environment included an expansive fenced lawn with a walking track, a beautician and a country club type atmosphere. The director described it as a therapeutic, recreational-based program with activities designed to provide physical, mental and social stimulation. A screening process excluded clients with aggressive or combative behaviors and those who developed incontinence. There was very little public disclosure of client conditions by the staff in Courtyard ADC. In a private meeting with the director, she estimated 10% of clients were low functioning-and could not participate in most activities. Those with greater cognitive ability were encouraged to help with tasks, such as the lunchroom. Friendships were common, and some higher functioning clients helped those with greater needs. Occasionally those with Alzheimer’s disease were known to sound delusional, become agitated, swear or yell out. Usually, staff reactions were not punitive. Discrete bathroom assistance was obtained without humiliation or public disclosure. “What’s his situation?” was staff code for –does he need help toileting? Observations only identified two staff who used infantilizing names for clients, such as “sweetie” or “the kids.” These were senior volunteers and sometimes referred to themselves as “mom.” One of the younger brain injured participants told the researcher he calls her mom as a term of endearment because she helped him with his seizures. The philosophy of this center was to use “minimal control, the majority of the time.” They seemed to have a good balance of autonomy and security. However, one of our observations noted two men had escaped the grounds—a very serious situation. They were later found, scared but in good condition.

Clients were invited to design and participate in activities, and

they could decline (force was never used). Those who were tired

or overstimulated could excuse themselves to a private area with

a bed. The activity schedule included day trips off campus and

invited performers. Observations occasionally heard these visitors

using baby-talk voice to clients. Visiting Movement Therapist VMT

came several times and was never observed to infantilize. The term

“behave” was used once or twice among clients to tease each other.

Given the typical freedoms, participants were sometimes intolerant

of a controlling request by staff members. A volunteer asked clients

to clear the aisle and go sit down in a chair. Mr. F mumbled “I’m

sick of this shit.” Another client had a known history of symptoms

including mild aggression, violent thoughts and delusions. Staff

were told to “smother her with kindness” to counter difficult

behavior. Out of the blue Ms. A said,

Ms. A: Are you suggesting I’m a murderer? …You are not

protecting me…you think you’re funny, don’t you?

Volunteer Staff 1 (VS1): Are you in a bad mood?

Ms. A: You scavenger.

VS1: That’s right, I’m a scavenger.

Ms. A: Scoot over so I can have a little bit of room (on the bench)

VS1: Will you be quiet? How much more room do you need?

Volunteer Staff 2 (VS2): Gosh she’s being nasty.

VS1 Yea, she’s being nasty today. (Ms. A hit a client) Hey, hey,

no hitting!

VS2 I think we better put her in the back room. No hitting.

Ms. A: I’m just making a statement (grumbling)

VS1: Shh! Pretend you are in the library or church.

Ms. A: Do you think that is funny? (Walks across the room) If I

should die, you guys would all be happy. (She said something to

Male Staff 1)

MS1: Ms. A, why are you so mean to me?

VS1: Why is she mean to all of us?

Female Staff 2: Do you need a hug today? (To Ms. A)

Ms. A: Well, that isn’t what I was going to talk to you about.

Female Staff 2 requested to look at researcher’s field notes and the observer showed her the handwritten memory prompts. After that incident, Ms. A was never seen in the center again. Humor and laughing were much more common in the relaxed atmosphere of Courtyard ADC. Male Staff 1 yawned and Ms. C joked “Do you get paid for that?” He laughed and agreed. Ms. C then threatened to send a picture to his mother. Clients with high function occasionally asked about the researcher’s studies.

Mr. W: I’m doing pretty good for an old guy. Some of the people here are totally out of it and others are fine. Like me, I have Parkinson’s disease …my body is starting to deteriorate, but my mind is still strong. Others here are not so lucky. Guess how old I am?..72.”

Small center was constrained by size, and dining took place on fold out tables. Outdoor options were limited to a group walk in the parking lot. Otherwise, 8-10 people interacted in one multipurpose room, with some child-oriented items, such as a doll and a dead rubber chicken. Volunteerism was part of the productive culture in Small ADC. The setting appeared homey, but with occasional holiday or activity-oriented décor. Activities were 22% infantilizing. Orientation exercise was too basic (“what state are we in?”) and they played a game where they give a little spank on the rear if someone bent over. Overall, the atmosphere and majority of activities were age appropriate. Upon entre, the director said “We are all family here. Sometimes we have nicknames for our clients, and they have nicknames for us. They aren’t degrading, it just shows how close we are.” We observed one use of a nickname (Smiley) and no reprimands used in Small ADC. Activities were scheduled, but usually optional and sometimes clients slept in chairs, or on a daybed, undisturbed. Unscheduled time to relax was common. Staff A to researcher “This is …our one-on-one time, so don’t think we are boring.” The Director described a screening process (clients must feed and toilet themselves, with no ‘word spaghetti’ and they are given a 3-day trial period). She also strategically moved lunch to 1pm, to allow for meal volunteerism and to “prevent sun-downing” in the afternoon. Repetitive activities included state bingo and bean bag toss, which sometimes lasted more than one hour. While playing high quality Velcro darts, the director used humor as she advised clients to try swearing at the board as you throw—for good luck. Obviously, a departure from the infantilized settings, where swearing would result in punishment, such as “time-out.” We observed a loud music exercise where one over-stimulated client shouted, “settle down!” When it continued, she took a break in the restroom for a while.

An interview of Ms. S from Small ADC asked about the staff, she said “Umm, they’re friendly. They try really hard. I think they … are a little critical.” She later pointed out that the activities are a bit repetitive, but “I go along with it.” All of the interviewees felt they had close friendships and interactions. Ms. B described losses in her life (money management, driver license, health crisis, co-residence with daughter). Regarding Small ADC she said “I have people tell me that I am doing better than I did…I feel better about myself too. I’m getting more confident all the time.” Mr. T, a former auctioneer described why he attends “I can’t just sit around and twiddle my thumbs.” He believes he helps others “I sing the songs…I push wheelchairs [on walks] …bring a few jokes.” In addition, he was a major contributor to the set and clean-up of meals, which is not unlike his behavior at home where he does yardwork and shovels snow for needy neighbors.

The only time ‘behave’ was mentioned was when Mr. R’s wife arrived, she put her hands on another client Mr. M’s shoulders. Staff A said, “Mr. M never behaves.” And she responded, “I know he doesn’t.” Staff A and R’s wife stepped out to the hall and talk about him, looking at him from the doorway. Ms. S asked Mr. R if that was his wife and he joked, no “It’s my mother.”

Clients in Small ADC felt free to approach the observer and have

a conversation, which occurred 19 times in 40 hours.

Ms. S: That’s great you’re coming to learn more about us old

people. We are neat…it is important that people watch us.

Ms. H: Learning how to act when you are old? (laughs).

Ms. K What are you doing now? I [also] like watching amusing

people who don’t know they are being amusing.

Ms. M: Some are ½ here, and some are ¾ here. Did you write

that down? Write that I am all here…Are you all here?

Sense of humor was frequently observed, with almost continuous laughter in Small ADC. One day, between activities Staff A said, “Make some noise.” Mr. T barked like a dog and told a joke “UPS and FedEx join forces; the new name is FedUp.” Mr. C laughed loudly. There were several instances of ‘potty humor’ and when Staff C tried to keep it quiet, Ms. M corrected her “Oh we’re all adults here.” Staff C later joked about it.

Multipurpose Senior Centers

Moving the discussion to voluntary organizations, the multi-purpose senior center (MSC) clientele was healthier and more independent than other services. They were ‘joiners’ and attendance and/or participation were voluntary. With looser rules, we did not observe instances of reprimands or deference obligations. There were, however, managerial differences which led directors to be more controlling in Food and Dance MSCs, compared to the self-governed Diversity MSC. In the latter, participants were encouraged by the senior council to make decisions and run the desired programs themselves [18].

In the 40 hours of observation in Food MSC, the researcher was

approached 17 times by participants who sometimes joked and

monitored her work.

Mr. TA: (approached 3 times) I’m going to censure everything

you write. Everything.

Mr. BA: What do you know today? You’re supposed to take your

smart pills!

Mr. J (joked) “Is she grading me? …I’m gonna flunk! Then can I

get kicked out of here?

Ms. Lo: Well, yes, you better behave!

Ms. P: Are you writing notes about us old ladies? You tell them

we are a bunch of racy, sexy, old ladies. I don’t care what people

think!

The Dance MSC had a stage with music for dancing, the primary

activity. Lunchtime was dominated by the director’s inappropriate

announcements and jokes, preventing dialog among participants.

Interviews specifically indicated a level of resentment toward

that management style, due to interrupted conversations. Dining

seat territoriality was a major theme, with disruptions caused by

someone sitting in the wrong seat [18]. The number of participants

attending meals was typically 26-32, but special programs drew

100. Clients approached the researcher 36 times, with assertive

inquiry or advice. Examples include:

Ms. N: I want to know what you are tediously doing? [senior

centers] are the best thing that ever happened for the elderly…

mature people.

Ms. S (dance instructor participant) You look like a student

who is doing a study on older women dancing (gave an orientation

about MSC participants). You know what you ought to do? Have us

perform and you’d get an A! I got my master’s in social work …they

told me the older you get you should slow down. Here are ladies in

their 70s and 80s who aren’t slowing down. We are fighting it. I’m

going to tell everyone what you are doing.

Mr. A: You writing a story? … ‘What I saw in the old folk’s

center?’ I could teach you everything you need to know about

anyone here in two seconds.

Mr. AN See we’re not old, that’s right, he’s just half dead!

(Laughing).

Two dancer women joked “Did we pass?” and “Taking notes about how bad we are?” Overall, there was a sense of humor among participants and a lack of deference obligations noted. The observer made no attempt to shelter her notes, so clients were able to see them as they passed.

The Diverse MSC was located in a spacious building with several

rooms to interact, do crafts and exercises. Self-governance meant

control was in the hands of participants. Officers had prominent

pictures in the front foyer, for recognition. Activities were voted

on and implemented by participants. Daily decisions were made

regarding all aspects of social and financial decision-making. The

director was available for consultation but remained backstage.

The researcher was approached 28 times by participants. On the

most populated days there were between 90 and 100 in attendance.

Territoriality was absent from this center, as participants controlled

larger programs and did not need to reserve and fight over dining

chairs (See Salari et al, 2006). The participants were inquisitive

about the researcher’s purpose as an observer.

Mr. I: You getting a lot of information for your articles, with us

as guinea pigs?

Mr. CA: Can I read what you are writing?

Mr. M: What are you doing here? They send you down here to do

the work... How old is your professor? Young professor, sending

down someone younger to see what older people want.

Ms. D (regarding her tap-dancing group) We’re booked for a lot

of performances over Christmas, this center is one of the most

active…You should join us (Tai Chi).

These quotes reflected critiques, research advice and pride associated with sharing talents. All illustrated a high level of confidence from the consumers and the sense of self was intact.

Discussion and Conclusions

The COVID-19 virus public health emergency which initially devastated the older population required extra-ordinary closures, isolation and social distancing in aging services and residence facilities. Evidence suggests the coronavirus led to increased isolation and a greater vulnerability to mistreatment within families and long-term care. This era of recovery from this dark collective experience provides a unique ability to restart these services and come back better than they were in the past. New attention to the sanitary conditions, practices and rules about staying home if one has symptoms of a contagious illness have been prevalent with reopening. I would argue we take this time to change the psychological treatment as well, abolishing deference requirements and infantilization among adults in aging services.

This comparative ethnography of three types of aging services analyzed data collected across 10 formal environments and included 420 hours of observation and 74 insider interviews. This has been the first comparative analysis of all these settings together. The themes discussed here were associated with place rules, deference requirements and the sense of self. Voluntary organizations included 3 multi-purpose senior centers (MSC) with ‘joiner’ participants, who were relatively healthy and socially active. Assistance needs were most intense in the total and partial institutions, with observations of 2 long term care facilities (LTC) and 5 adult day centers (ADC). The latter two types were settings containing consumers most vulnerable to infantilization, restrictive place rules and requirements of deference. In the most severe cases, staff members kept tight control in the environment, sometimes even limiting social interaction and friendship formation. These were the locations where ‘inmates’ sense of self was in jeopardy as they dealt with three behavioral choices: 1) withdrawal, 2) show deference or 3) challenge staff with aggression (negative deference). These will be explained in more detail below. Rather than revisiting services one by one, the discussion will address concepts and themes—beginning with the most oppressive environments.

Goffman [12,49] introduced the notion of a total institution, as a confining setting without opportunities for normal discourse, therefore making it challenging for ‘inmates’ to retain their identities. Partial institutions [19] are also at-risk for harm to the sense of self. This research found some settings made it hard to be a person. Environments exerted their own level of press, and personenvironment congruence became more strained when consumers had dementia and/or physical limitations [43]. Poor health increased the vulnerability in controlled settings, as it exposed consumers to reprimands and humiliation—but Kitwood [25] and Salari [16,18] have argued for humane treatment, no matter the cognitive status. Punitive treatments should be reduced as a management technique, as loss of self can be prevented through the provision of least restrictive environments.

Evidence supported the notion, that, in the most restrictive settings, consumers were required to comply with the rules and demands of caregivers, or risk being considered a troublemaker [13]. Offenders included some but not all residential facilities and partial institutions. Public punishments and humiliations are a daily reality for some settings, but adults are thought to organize their lives around avoiding these experiences [32]. Symptoms of dementia may include a decline in inhibitions, which interferes with mechanisms that would normally warn us to be polite and sociable. Misinformed or untrained staff members were observed to press down harder to ‘teach’ consumers the place rules—with an added level of shame for transgressions that forgot the norms of public behavior. Deference displays represented subtle attempts to prevent reprimands among those who feared ‘troublemaker’ shaming, in a setting that was already hyper-sensitive to this exposure. Reprimands, combined with child-oriented environments, erected barriers to healthy autonomy. A message of subordination was sent to the individual, requiring deference to avoid costly conflicts. Some infantilized persons showed challenge behaviors toward staff and institutional goals, but these were met with negative repercussions. Public punishments of one person socialized others in the group with the need to ‘behave.’

Goffman [49] would argue the total institution is the most restrictive, due to full-time exposure. We did find Medical LTC fit into the practices that would lead to self-mortification, including the lack of social activities and the dull existence surrounding the nurses’ station. Staff culture included agreement among nurses to reprimand or ignore ‘troublemakers.’ References to ‘sun-downing’ reflected the belief that behavioral problems were biological and thus inevitable. Self-continuity including adult status was difficult to maintain on the inside. We observed a new resident who was introduced to Medical LTC with immediate eruptions of conflict. She was not yet accustomed to authoritarian orders to ‘sit down” and physical barriers to her goal achievement. Other residents with more long-term exposure seemed to be numb, as they asked the observing researcher “have we behaved?”

Partial institutions Elementary, Intergenerational and Church ADCs were more inhumane than Hospitality LTC, so we will return to discuss that residence facility later. All three ADCs mentioned here were among the most restrictive environments, as they forced participation, used frequent reprimands and repeated the need to ‘behave.’ The language was both judgmental and infantilizing when nicknames such as brat, bad girl/bad boy and ornery were repeatedly bestowed upon consumers. The use of the term ‘girl’ or ‘boy’ has historically been a mechanism for discrimination and denying adult status. The repeated reference to adults in this manner was reminiscent of how African Americans have been treated in the public discourse (particularly in the U.S. Deep South region). The effects on the person targeted were not insignificant. We saw people adopt some of these terms to refer to themselves, suggestive of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Insider interviews were helpful to gather insight from consumers about damage done to the sense of self with the harsh enforcement of place rules and other infantilizing experiences. For example, Ms. C (Church ADC) repeated (several times) her need to remain on the correct side of the staff opinions. Consumers probably absorbed the practice of assigning reputations for others’ misbehavior in these environments and feared they would be next. Reputations as a “bad” actor were not easily shaken, as the institutional memory held a long-term grudge, even without corresponding evidence to warrant the reaction. These labels reduced the ability for consumers to socialize freely or express opinions.

These three offending ADC environments utilized repetitive maladaptive activities to place clients in child-oriented memories, as though they were teaching a “moral lesson” to socialize compliance with place rules. Participation was mandatory, and rewards were based on being “good.” Those who asserted their preferences not to participate were viewed as troublemakers and punishments included pressure to sit down and even placement in ‘time-out.’

This comparative ethnography indicated removal of access to positive demeanor pushed those confined individuals into a spot where could only 1) show deference (and try not to be a troublemaker), 2) withdrawal or 3) challenge the staff and environment. Typically, deference was shown to be asymmetric, one-way directionally from consumers to staff. However, there were instances observed in constrained environments where forced deference was contagious, as peers attempted to enforce rules on each other (symmetric deference) [49]. Relevant forces shaping the sense of self included the perceived opinions of others--staff, family or society, which viewed certain consumers as bad, ornery or needing to behave. A self-fulfilling prophecy was adopted—in ways that could be both seen and heard.

Two of the adult day centers were typically free of reprimands and had little or no use of the word “behave.” As a result, we can point to their brand of service as more ethical and adult oriented. Our evidence does not condemn all adult day centers, as only the most infantilized settings conveyed the message to show asymmetric deference. As an example, swearing was an offense to place someone in time-out in Intergenerational ADC, but in Small ADC, consumers were encouraged to swear for good luck as they threw Velcro ‘darts at a dartboard. While some may obsess over the vulgarity in the second environment, the constant conflicts and humiliations in the first could be seen by others as equally or more offensive. Similarly, “sun-downing” was a problem for the most controlled settings (Medical LTC). However, tricks such as moving lunch one hour later allowed Small ADC director to provide volunteer activities in order to suppress afternoon fatigue and behavioral problems.

Unlike, Medical LTC, Hospitality LTC activities were reliable and accessible. Residents considered the activity directors their friends. Interviews indicated a few staff members might be imposing their values (such as bathing), but consumers used strategies to survive, with the sense of self still intact. Insiders fought to adapt and retain images of their worth, independence, social connections and contributions (i.e., maverick/businessman, the TV news celebrity and the happy hour attendee). The definition of a maverick includes an independent minded person, a dissenter “someone who refuses to conform to an established set of standards of conduct [57].” When staff attempted to impose controls, the maverick reacted to “speak right back.” To save face, he also attempted to distance himself from the group—particularly those he viewed as “limited.” The reasons for separating his identity from theirs was because some staff spoke to him as though he was limited. Health problems and institutional living knocked down these respondents’ selfconcept, but they were able to articulate what they did and did not appreciate in the setting. Aging environments must ask themselves; do we have excessive rules? And are the participants expected to show deference to staff in order to avoid being labeled a troublemaker? Ultimately, the freedom to interact, be creative and form friendships in the setting can be encouraged or discouraged [16,17]. The structure of activities needs to be consumer motivated and taken seriously, with voluntary participation instead of central mandatory activities. Escape mechanisms are important for preserving adult status.

Voluntary organizations were different from full and partial

institutions in several ways. First, participants lived independently

in the community and had fewer cognitive and physical health

limitations. Second, these services compete for participants, giving

more incentive to provide adult status, meaningful activities and

displays of talent and skill (competence). Third, “joiners” were less

likely to feel pressured to follow rules or “behave” because they had

other options. A Diverse MSC member interview described a center

he had once attended in the past with a controlled environment and

an overbearing director.

Mr. F: We didn’t like it…We didn’t like the people running it. The

gal…says “We’re gonna do it our way or we’re not gonna do it at

all” …Well about half of us quit…I didn’t go anywhere for a long

time. Here [Diverse MSC] I’ve had a good experience. I love to

come here…You have a choice to go do what you want.

This represents the benefit of voluntary participation and choices of other outlets for interaction. Those consumers enjoyed the freedom to go elsewhere and could explore another location for self-preservation. In appropriate environments, participants feel empowered. When given the choice to be a joiner, retention of personal power is part of the decision-making process and consumers are in a beneficial position. To be a “joiner” means you can also “unjoin” if the management style does not suit your needs. Retention of a strong sense of self in this study was evidenced by assertive inquiry, as MSC participants questioned the observing researcher and felt compelled to give advice about what types of things she could study and what happens to her results. This was also a time for prideful recounts of their own educational achievements and the role they played in the MSC. We also witnessed a healthy sense of humor in these environments. In the most self-directed MSC, there was no conflict surrounding dining chair territoriality, but instead friendships formed through mutual ownership of the entire center [18]. Negative reputations were never observed among voluntary organization participants—but we did see the potential for star power among some who shared talents instructing a dance group or facilitating an art class.

Voluntary organizations had within group differences noted as MSCs with an overbearing director, tended to foster a lowered participation, and displays of dining seat territoriality and conflicts. For example, Food MSC had very few who would voluntarily participate, so the director had to call consumers at home to persuade them to attend her book club, etc. Those in attendance watched as the director made all the choices about books and told them what to think about the selection. Participation was forced and attendees were disenfranchised. Withdrawal (almost catatonic) was the most common response to the boredom.

On the other hand, when a strong senior council self-governed the center (Diverse MSC), participants could tailor activities to their interests and run the programs. These were the environments least likely to require adherence to strict authoritarian rules. Perhaps because they are voluntary, joiners picked those programs that gave the greatest amount of autonomy and freedom. Volunteerism in that center gave participants the freedom to choose what they do with their time, without feeling controlled, belittled or reprimanded.

This research has both strengths and limitations. The results are not intended to be generalizable, but instead provided a discussion platform for similar aging environments. These observations and interviews were conducted in the 1990s and early 2000s— hopefully, infantilization is reduced with privacy policies such as HIPAA and the recent advancements in person-centered culture. There is more transparency with facility evaluations publicly posted online in long-term care. However, surveying these postings point to several institutions with chronic and persistent offences to quality of living. Unfortunately, there could also be roll-backs to the modern progress with the disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic as these settings were placed into survival mode. Decades of neglect were uncovered as emergency responders stepped in to assist with the fallout from the pandemic. This research had the benefit of many diverse settings, with 10 separate cultures examined. More recently in 2010, the author observed 72 hours in two skilled nursing and one hospice facility for another project. Those environments seemed more evolved than the primitive daily experiences observed in the most infantilized settings of the original study. In facilities, specialized dementia units now separated the severely impaired from those who could benefit from greater cognitive challenges. These changes are mutually beneficial and represent efforts to provide autonomy and security without physical or chemical restraints (to prevent wandering off campus or other dangerous outcomes). However, even in the modern facilities, there were struggles noted, such as extreme staff-resident conflict which surrounded bathing rituals (based on screaming and fighting noises coming from showers). These were challenging tasks, because a lack of bathing becomes a public problem, and one simply cannot go long stretches without. Technology has assisted, but clearly there are needs for more improvement. It should also be noted, the follow-up study had planned to include observations from an additional SNF with 104 beds. Unfortunately, the facility director refused to grant the researcher admission. This may have been related to a very poor ranking on the published nursing home quality indicators, which cited ‘multiple deficiencies,’ as well as concerns about elder abuse and neglect. In other words, it is likely that we continue to have modern settings similar to those described here.

Services must adapt to the needs of baby boomers and provide humane and ethical social solutions. Expectations of this cohort (and beyond) will require a more person-centered philosophy beyond the acute pandemic era, where aging services consider public health conditions, reduce rigid rules and listen to the preferences of consumers. Unfortunately, the changes spurred from the global pandemic have included difficulties finding employees to fill positions in aging services. This may result in overburdened staff, and the person-centered ideals may be put on hold.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to R. Carboni, J. Eaton, M.Rich, G. Towsley, and D. Uriona for research assistance. University of Utah Research Grant funded the observation of multipurpose senior centers and some of the adult day centers in this study. Funding for the comparison sample described in the discussion was obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau.

Conflict of interests

None.

References

- Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H (2014) An Aging Nation: The older population in the United States. Current Population Reports, Census.gov P: 25-1140.

- West LA, Cole S, Goodkind D, He W (2014) 65+ in the United States: 2010. Current Population Reports U.S. Bureau of Census, census.gov P23-212.

- Shiels Meredith S, Almeida Jonas S, García-Closas, Montserrat (2020) Impact of Population Growth and Aging on Estimates of Excess U.S. Deaths During the COVID-19 Pandemic, March to August. Ann Intern Med.

- Johns Hopkin’s University 2021. The Impact of Covid 19 on Older Adults (Accessed 2/27/2021).

- D’Cruz Margita, Banergee Debanjan (2020) ‘An invisible human rights crisis’: The marginalization of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic – An advocacy review Psychiatry Research 292: 113369.

- Duke Han, Mosqueda Laura (2020) Elder Abuse in the Covid -19 Era Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 68(7): 1386-1387.

- Elman Alyssa, Breckman Risa, Clark Sunday, Gottesman Elaine, Rachmuth Lisa, et al. (2020) Effects of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Elder Mistreatment, Journal of applied gerontology 39(7): 690-699.

- Makaroun Lena K, Bachrach Rachel L, Rosland Ann-Marie (2020) Elder Abuse in the Time of COVID-19 Increased Risks for Older Adults and their Caregivers 28(8): 876-880.

- RM Werner, AK Hoffman, NB Coe (2020) Long-term Care Policy After Covid-19 Solving the Nursing Home Crisis, New England Journal of Medicine 383(10): 903-905.

- Sedenski Matt and Condon Bernard Public Broadcasting System PBS (2020) As Covid Deaths Soar, Nursing Home Deaths Caused by Neglect Surge in the Shadows.

- Viera Paul (2020) Coronavirus Lays Bare Poor Conditions in Canada’s Nursing Homes, Wall Street Journal 6.24.2020.

- Goffman E (1961) Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. NY, Doubleday.

- Gubrium J (1976) Living and Dying at Murray Manor, New York, St. Martin’s Press 76(8): 1337.

- Kane R (2001) Long-term Care and Good Quality of Life: Bringing them closer together. The Gerontologist 41(3): 293-304.

- Liou C, Salari, S (2020) East and West Ethnography in Adult Day Services: Lessons from Taiwan and the United States, Paper presentation Gerontological Society of America Annual Meeting 4(Issue Supplement 1): 516.

- Salari S (2002) Intergenerational Partnerships in Adult Day Centers: Importance of age-appropriate environments and behaviors. The Gerontologist 42(3): 321-333.

- Salari S (2005) Infantilization as Elder Mistreatment: Evidence from five adult day centers, Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect 17(4): 53-91.

- Salari S, Brown B, Eaton J (2006) Conflicts, Friendship Cliques and Territorial Displays in Senior Center Environments, Journal of Aging Studies 20(3): 237-252.

- Salari S, Rich M (2001) Social and Environmental Infantilization of Aged Persons: Observations from two adult day centers. Int’l Journal Aging & Human Development 51(2): 115-134.

- Malonebeach EE, KL Langeland (2011) Boomers’ Prospective Needs for Senior Centers and Related Services: A survey of persons 50-59. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 54(1): 116-130.

- Pardasani Manoj (2019) Senior centers: if you build will they come? Educational Gerontology 45(2): 120-133.

- Wick Jeannette Y (2012) Senior centers: traditional and evolving roles. Consult Pharm 27(9): 664-667.

- Chambré SM, Netting FE (2018) Baby Boomers and the Long-Term Transformation of Retirement and Volunteering: Evidence for a Policy Paradigm Shift. Journal of Applied Gerontology 37(10): 1295-1320.

- Eaton J, Salari S (2006) Environments for Lifelong Learning in Senior Centers, Educational Gerontology 31(6): 461-480.

- Kitwood T (1997a) Dementia Reconsidered: The person comes first. McGraw-Hill, Maidenhead UK.

- Edwardson E, Innes A (2010) Measuring Person Centered Care: A critical comparative review of published tools. The Gerontologist 50(6): 834-846.

- United States Senate (2009) Person Centered Care: Reforming services and bringing older citizens back to the heart of society. Hearing Special Committee on Aging, Washington, D.C. 110th Congress, 2008. Serial Number 110-133.

- Sedikides C, Wildschut T, Grouzet F (2018) On the Temporal Navigation of Selfhood: The role of self-continuity, Self and Identity 17(3): 255-258.

- Marson SM, Powell RM (2014) Goffman and the Infantilization of Elderly Persons: A theory development. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 41(4): 143-158.

- Uriona D, Salari S (2002) Hospitality vs. Traditional Environments and Behaviors in Assisted Living, Gerontological Society of America Annual Meeting November Boston.