Research Article

Research Article

Frailty Screening of Older Adults in the Context of Primary Health Care

Hajar Ziaeefar1*, Abolghasem Pourreza2, Maryam Tajvar3, Hoseein Matlabi4 and Mehdi Yaseri5

1Healthcare Management PhD. Dept. of Health Management and Economics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2Professor. Dept. of Health Promotion and Education, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Assistant Professor of Healthcare Management. Dept. of Health Management and Economics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences,Tehran, Iran

4Research Centre for Integrative Medicine in Ageing, Ageing Research Institute, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

5Associate Professor Biostatistics. Dept. of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Hajar Ziaeefar, Healthcare Management PhD. Dept. of Health Management and Economics, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Received Date:October 10, 2022; Published Date:October 26, 2022

Abstract

Background: Older adults are high risk to chronic diseases that lead to increased frailty and mortality as well as increased pressure on the

health system, through screening and early detection of frail older adults in primary healthcare, the associated complications as well as mortality

can be reduced. The aim of this study is frailty screening of older adults based on chronic diseases.

Method: This quantitative cross-sectional study was conducted in Tehran (Iran) in 2019. A two-stage cluster sampling method was employed.

Level of frailty were screened by the PRIZMA-7 questionnaire. The Questionnaire was piloted with18 respondents. The test-retest reliability score

for the questionnaire was r=0.82, p<0.001. Data analysis of the questionnaire was conducted using nonparametric tests and Logistic Regression

model by SPSS software Version 22.

Results: frailty level of 76 ≤ years’ old people were 12.59 times higher than people aged 65-60 years. Frailty level of men was 0.97 times higher

than women, which was not statistically significant. Median (Q1-Q3) frailty of 99 older adults who suffer from cardio diseases was 1(1-2) and it was,

1(0-2) for older adults who did not. Median (Q1-Q3) frailty was 2 (0-4) for 149 older adults with bone disease and 1 (0-1) for people who did not.

According to Mann-Whitney test, these difference for both diseases were statistically significant (p-value <0.001).

Conclusion: Early detection of older adults in the age group of 76≤ years and the older adults who suffering from cardiovascular and bone

disease can be more effective to decrees frailty consecutions.

Keywords:Frailty; Brief screening; Older adults; Chronic disease; Primary care

Introduction

Older adults’ people are a highly heterogeneous group. Their life courses of health and functional status vary substantially, depending on their genetic, biological, and environmental backgrounds as well as other physical, psychological, and social factors. Therefore, individuals with the same chronological age can have different biological ages [1].

Besides aging, chronic diseases and frailty occur that represent the clinical expressions of the accumulations of biological deficits.

However, when addressing chronic diseases, the evaluation of frailty is yet far to be part of routine clinical practice. Frailty and chronic diseases are often treated as different identities. However, the two concepts are related and present a certain amount of overlap and the presence of chronic diseases contributes to the onset of frailty. Frailty is a good descriptor of complexity found in older age [2]. Also has been viewed as a cornerstone of geriatric medicine and a platform of biological vulnerability to a host of other geriatric syndromes and adverse health outcomes [3].

Frailty can begin before 65 years of age, but the onset escalates in those aged 70 years and over [4]. Its estimates that a quarter to a half of people aged 85 are considered frail [5]. Frailty as an age-related state decrease physiological reserves that characterize by a weakened response to stressors. it contributes to the dynamic progression from robustness to functional decline. Because of this, it is frequently defined in terms of absence of resilience that predisposes to disability and dependency on others for daily life activities, and that leads to hospitalization and institutional placement [6,7].

The incidence of frailty has been estimated at 71.8/1000 person years in the Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS),3 22.5 to 38.7/1000 person years in the Precipitating Events Project,9 and as high as 191/1000 person years in women from among the onethird most disabled living in the community in the Women’s Health and Aging Study I [2]. Therefore, Frail older adults are at increased risk of premature death and various negative health outcomes, including falls, fractures, disability, and dementia, all of which could result in poor quality of life and increased cost and frequently use of health care resources, such as emergency department visits, hospitalization, and institutionalization. Multiple studies using cohorts of community-dwelling older adults have showed that the health care costs of frail individuals are sometimes several-fold higher than those of non-frail counterparts [1].

These consequences of frailty imply ‘ageing in place’, which corresponds to the preference of older people to grow old in their own homes. Due to ageing in place, GPs and other primary care professionals become mainly responsible for the care for this growing number of frail older people. This means that the degree of complexity of the patient population in primary care is increasing. Primary care professionals struggle with this complexity and the quality of care is under pressure [4-9].

It is crucial to be able to identify patients earlier, so interventions such as brief “risk screening” tools and Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) is needed [10]. Time investment is a major limitation in applying a full CGA in a busy practice. In order to fit into primary care physicians’ tight schedule, several combinations of short instruments to identify geriatric conditions have been proposed. One of these is PRISMA-7, being an abbreviation for

‘Program of Research to Integrate Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy’. Researchers developed PRISMA-7 as part of a large Canadian study and used it as a case-finding instrument to identify frail older adults in the community. PRISMA-7 is a questionnaire with seven dichotomous questions each scoring 0 or 1 point. A score of ≥3 is considered indicative of frailty [9-12].

Frailty screening of the older adults provides valuable and necessary data for planning and implementing intervention strategies to maintain functional status or control the progression of the adverse and inevitable outcome of aging [9-13].

In view of the above, the aim of this study was to screen Frailty and chronic disease of older adults in the context of primary health care which to identify frail older adults based on their chronic diseases.

Materials and Methods

This quantitative cross-sectional study was performed among older adults’ people across primary health care centers located in three districts of Tehran (North, Northwest and South) in 2019, Iran. Inclusion criteria for the setting and the older adults were as follows: Primary health care centers which are affiliated to TUMS1 and IUMS2. The sample older adult’s age was 60 years old or above who had active health records in primary health care centers, they were also able to communicate and answer the questionnaire items by phone. The exclusion criteria were the 60-year-old or above older adults with active health records but unable to communicate or answer the questionnaire items by phone.

The sampling was based on a two-stage cluster sampling. The first stage was proportional sampling clusters (PHC centers) and the second stage was the systematic random sampling of the older adults of the clusters.550 older adults were willing to participate in the study. Since the contact information of participants were available in the primary health care centers, the data were collected by phone call and also obtaining their consent.

The PRISMA-7 questionnaire was translated to Persian language; after agreeing to Persian translation, the text was translated back to English. The translation was compared with the original text. After agreement on the translation, questionnaire was piloted in 18 older adults. The final form has been applied in this study. Data of the 18 piloted older adults has not been included into the dataset. The test-retest reliability score of questionnaires was calculated. Using Pearson correlation coefficient, the correlation coefficient between before and after scores was 0.82, which was statistically significant (r = 0.82, p <0.001).

To present the data values we used Mean, Standard Deviation (SD), Median (first quarter-third quarter) and Range, frequency and percentage. The core statistical analysis was based on Mann– Whitney U test, Kruskal–Wallis test, and Logistic Regression by IBM-SPSS version 22, the level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

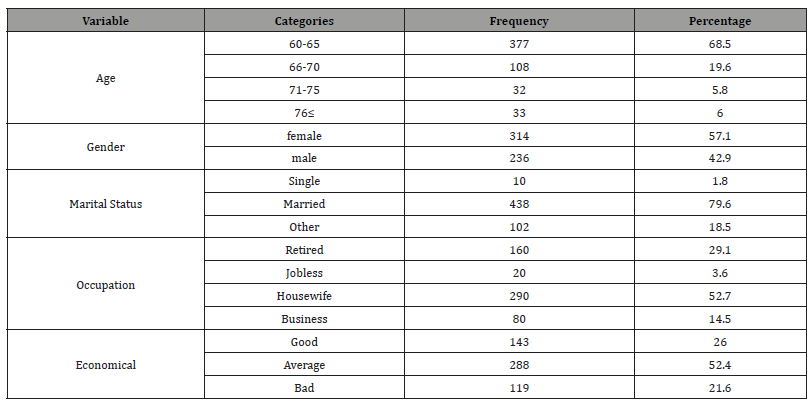

In this study, the number of older women was 314 (57.1%)

and 236 (42.9%) were male. The highest age group of the subjects

was 60-65 years (65.5%). Table 1 shows the other demographic

characteristics of the participants in the study.

• Tehran university of medical science

• Iran university of medical science

Table 1:General characteristics of older adult’s people.

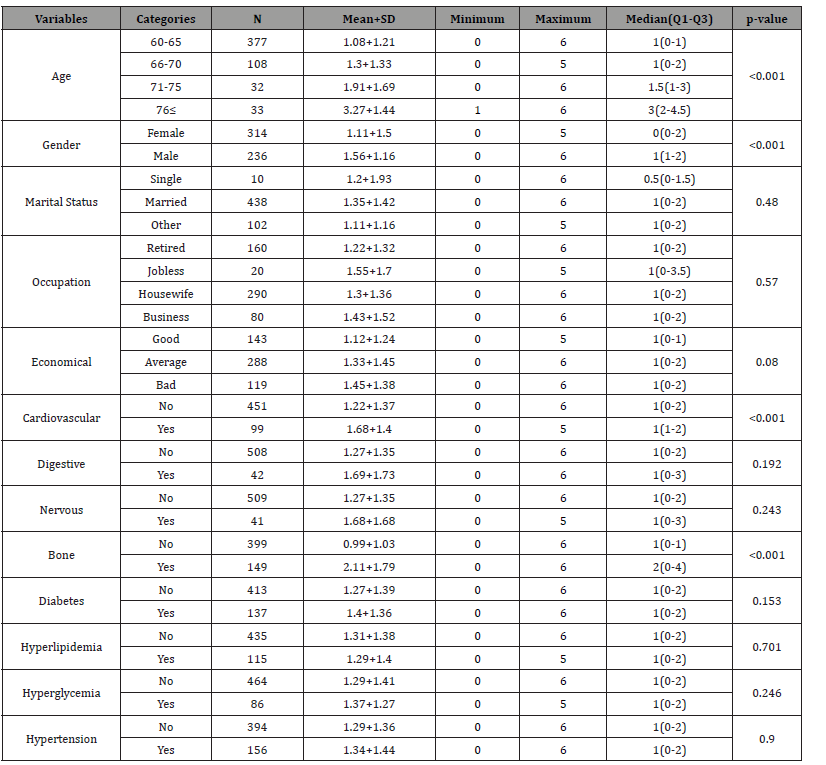

The Mean (SD) of the total frailty score for the participants was 1.30 (1.38). Also, the Median (Q1-Q3) frailty score was (2-0) 1. Table 2 shows the Mean and Median frailty score of the older adults based on socio-demographic characteristics and types of chronic diseases and pro-factors of chronic diseases (hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia and hypertension).

Table 2:General characteristics of older adult’s people.

According to Kruskal-Walli’s test, there was a significant relationship between frailty score in the older adults age categories (p-value <0.001), 76≤ years old older adults had the highest frailty and 60-65 years had the lowest frailty.

Median (Q1-Q3) frailty of men and women were 1 (1-2) and 0 (0-2), respectively. According to Mann-Whitney test, this difference was statistically significant (p-value <0.001).

Based on Kruskal-Walli’s test, no significant relationship was observed between frailty score in the older adults and their marital status (p-value = 0.48), occupation (p-value = 0.57), economic status (p-value = 0.08).

Median (Q1-Q3) frailty of 99 older adults who suffer from cardio diseases was1 (1-2) and for older adults who did not, was1 (0-2). Median (Q1-Q3) frailty was 2 (0-4) for 149 older adults with bone disease and 1 (0-1) for people who did not. According to Mann- Whitney test, this difference for both diseases were statistically significant (p-value <0.001).

Median (Q1-Q3) frailty was 1 (0-3) for older people who suffer from Digestive (42 older adults) and nervous disease (41 older adults) and also was 1 (0-2) for older people who did not. According to Mann-Whitney test, this difference was not statistically significant for Digestive disease (P-value = 0.192) and nervous disease (P-value = 0.243). Median (Q1-Q3) frailty of 137 people who suffer of diabetes was 1 (0-2) and for older people who did not, was1 (0-2). According to Mann-Whitney test, these differences was not statistically significant. (P-value = 0.153).

Median (Q1-Q3) frailty of chronic disease pre-factors of 115 older adults with hyperlipidemia, 84 older adults with hyperglycemia, and 156 older adults with hypertension was1 (0-2) and Median (Q1-Q3) frailty of older adults who did not was 1 (0-2). According to Mann-Whitney test, this difference was not statistically significant for hyperlipidemia (P-value = 0.701), hyperglycemia (P-value = 0. 246), hypertension (P-value = 0. 90).

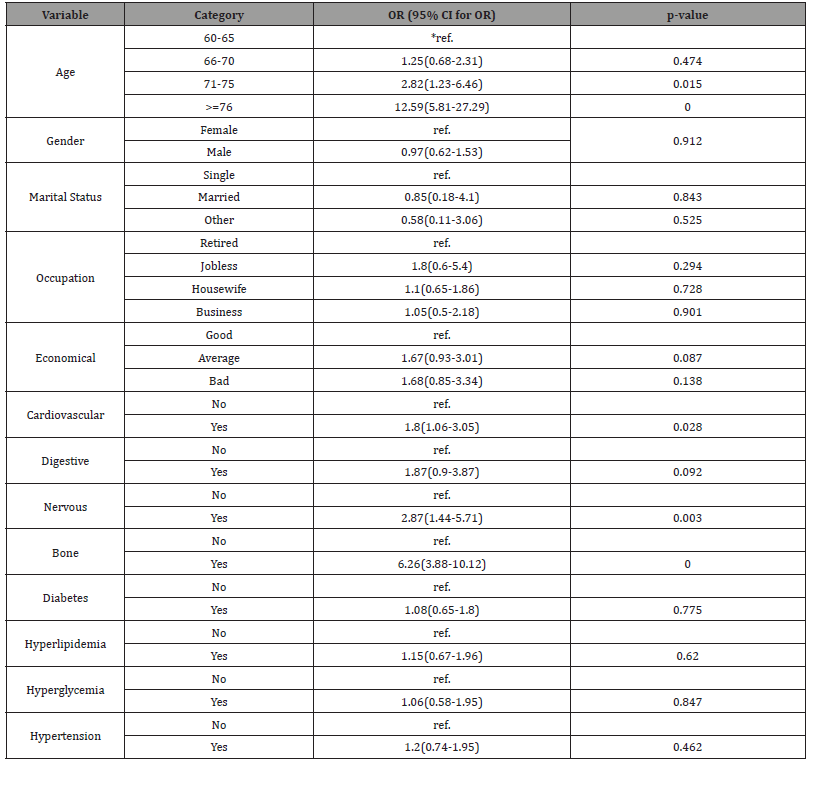

In the study, 92 older adults (16.7%) out of 550 identified as frail ones. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the effect of risk factors on the prevalence of frailty. The results of regression modeling are shown in Table (3).

According to Table 3, frailty level of people older than 76 years was 12.59 times higher than people aged 65-60 years. Frailty level of men was 0.97 times higher than women, which was not statistically significant.

Table 3:Logistic regression analysis of frailty in participant by demographic characteristics and chronic diseases.

*The first category of each group in the categories was considered as the reference group.

Frailty level of older adults with Cardio disease was1.8, Digestive disease 1.87, Nervous disease 2.87, Bone 6.26, Diabetic 1.08 times higher than compared to the older adults who did not suffer of these diseases.

In comparison, frailty level of older adults with Hyperlipidemia 1.15, Hyperglycemia 1.06, and hypertension 1.2 times was higher than the older adults who did not suffer from chronic disease pre factors.

Discussion

The findings of frailty screening showed less frailty (Mean=1.30) among older people in this study. It’s notable that 68.5% of participant were in the age range of 60-65 years old that maybe affected the mean of frailty. A previous study which used prizma-7 showed high frailty in the older adults of 65 years old and over [14]. Higher age demonstrated higher frailty in the older adult’s people [15]. It consists with findings of this study that the level of frailty increase eventually with aging. This study showed the higher frailty level increasing in age group of 75≤ years old people that is 12.59 times higher than of reference group (60-65 years).

According to the Mann Whitney U test, the gender and frailty has statistical relationship with frailty (p-value <0.001) but in regression logistic model frailty level of men was higher than of women. In a European study, the frailty-free years of women were significantly fewer than those of men, influenced by both biological and socio-economic factors [16]. And also, other study is found the prevalence of frailty to be greater in women [17].

A systematic review of 11 studies carried out in 2012 showed the prevalence of frailty in women was 9.6%, which was higher than that in men (2.5%) [18].

Frailty level of older adults’ people who suffer of chronic disease is higher than of the older adults who did not that is consist of the pervious findings [19, 20]. Our study revealed that suffering of cardiovascular and bone diseases have statistical relationship with frailty (p-value <0.001). A same study represented that the frailty prevalence of hypertension (53.1%), Osteoarthritis (70.8%), coronary heart disease (41.5%), Diabetes mellitus (25%), Congestive heart failure (13%) was respectively [2].

Our study stated that the hypertension has not statistical relationship with frailty (p-value = 0.9) that is in contrast of another study [21].

In a study, high rates of comorbidities (cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, and diabetes) were found to be associated with frailty [22]. Another study showed that chronic diseases were associated with frailty. The older adults who had history of falls over the past year were also more frail [23]. That it consists of our findings that showed the highest frailty in the older adults who suffer of bone disease among studied diseases (OR (95% CI for OR) = 6.26(3.88-10.12).

Conclusion

Our study concluded that it would be better to prioritize frailty screening of 75≤ year’s old older adults and the older adults people who suffer of Cardiovascular and Bone diseases. In addition, conducting the effective strategies such as older adult’s education to increase their knowledge and awareness of decreasing frailty ways in PHC centers is highly recommended. Notably, the findings demonstrated less frailty. Therefore, it is suggested to conduct similar studies to evaluate the components among 75-year-andover older adults to accurately identify target older adults’ people. Generally, the findings of this study can be considered by policy makers, healthcare providers, and older adult’s people.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the research ethics committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences under license ID IR.TUMS. SPH.REC.1396.4208. Informed consent was obtained from all the people who participated in the study.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Financial support and sponsorship This research was funded by Tehran University of Medical Sciences and health Services grant No 96-10–23-40540.

Acknowledgments:

We really appreciate deputy of research and technology for their valuable supports. We also are most grateful for the assistance given by the facilitators, all participants, and their family members.

Conflict of interest:

There is no conflict of interest. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article. None of the authors has received support for this work that influenced its outcome.

References

- Kojima G, Liljas A, Iliffe S (2019) Frailty syndrome: Implications and challenges for health care policy. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy.

- Weiss C (2011) Frailty and Chronic Diseases in Older Adults. Clinics in geriatric medicine 27: 39-52.

- Walston J, Buta B, Xue Q-L (2018) Frailty Screening and Interventions: Considerations for Clinical Practice. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 34: 25-38.

- Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, L Woodhouse, L Rodríguez-Mañas, et al. (2019) Physical Frailty: ICFSR International Clinical Practice Guidelines for Identification and Management. The journal of nutrition, health & aging 23(9): 771-787.

- Gee SB, Cheung G, Bergler U, Jamieson H (2019) There’s More to Frail than That: Older New Zealanders and Health Professionals Talk about Frailty. Journal of Aging Research.

- Apóstolo J, Holland C, Campos E, Silvina Santana, Maura Marcucci, et al. (2017) Predicting risk and outcomes for frail older adults- an umbrella review of frailty screening tools.

- Marcucci M, Damanti S, Germini F, Joao Apostolo, Elzbieta Bobrowicz-Campos, et al. (2019) Interventions to prevent, delay or reverse frailty in older people: a journey towards clinical guidelines. BMC Medicine 17(1).

- Carvalho V, Rossato S, Fuchs F, Erno Harzheim, Sandra C Fuchs, et al. (2013) Assessment of primary health care received by the elderly and health related quality of life: A cross-sectional study. BMC public health 13: 605.

- Nutakor JA, Gavu AK (2020) Frailty Screening Tools: Frail Detection to Primary Assessment. Elderly Health Journal 6(1): 64-9.

- Jang I-Y, Lee H, Lee E (2019) Frailty and Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment. Journal of Korean Medical Science 35(3): e16.

- Hoffmann Sarah, Wiben Amalie, Kruse Marie, Katja Kemp Jacobsen, Lembeck Maurice A, et al. (2020) Predictive validity of PRISMA-7 as a screening instrument for frailty in a hospital setting. BMJ Open 10(10): e038768.

- Raîche M, Hebert R, Dubois M-F (2008) PRISMA-7: A case-finding tool to identify older adults with moderate to severe disabilities. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics 47: 9-18.

- Sternberg S, Schwartz A, Karunananthan S, Howard Bergman, A Mark Clarfield, et al. (2011) The Identification of Frailty: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 59: 2129-38.

- Yaman H, Ünal Z (2018) The validation of the PRISMA-7 questionnaire in community-dwelling elderly people living in Antalya, Turkey. Electronic physician 10(9): 7266-7272.

- Zhang Q, Guo H, Gu H, Zhao X (2018) Gender-associated factors for frailty and their impact on hospitalization and mortality among community-dwelling older adults: a cross-sectional population-based study. PeerJ 6: e4326.

- Romero-Ortuno R, Fouweather T, Jagger C (2014) Cross-national disparities in sex differences in life expectancy with and without frailty. Age Ageing 43(2): 222-8.

- Muscedere J, Waters B, Varambally A, Sean M Bagshaw, J Gordon Boyd, et al. (2017) The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Medicine 43(8): 1105-1122.

- Hoogendijk E, Hout H, Heymans M, Henriëtte E van der Horst, Dinnus H M Frijters, et al. (2014) Explaining the association between educational level and frailty in older adults: Results from a 13-year longitudinal study in the Netherlands. Annals of Epidemiology 24(7): 538-44.e2.

- Ganz DA, Bao Y, Shekelle PG, Rubenstein LZ (2007) Will my patient fall? Jama 297(1): 77-86.

- Setiati S, Aryana S, Seto E, Sunarti, N. Widajanti, et al. (2017) Frailty status and its associated factors among indonesian elderly people. Innovation in Aging 1(1).

- Mousavi sisi M, Shamshirgaran SM, Rezaeipandari H, Matlabi H, et al. (2019) Multidimensional Approach to Frailty among Rural Older People: Applying the Tilburg Frailty Indicator. Elderly Health Journal 5(2): 92-101.

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, AB Newman, C Hirsch, et al. (2001) Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A 56(3): M146-M56.

- Moreira V, Lourenço R (2013) Prevalence and factors associated with frailty in an older population from the city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: The FIBRA-RJ Study. Clinics (São Paulo, Brazil) 68(7): 979-85.

-

Hajar Ziaeefar*, Abolghasem Pourreza, Maryam Tajvar, Hoseein Matlabi and Mehdi Yaseri. Frailty Screening of Older Adults in the Context of Primary Health Care. Glob J Aging Geriatr Res. 2(1): 2022. GJAGR.MS.ID.000526.

-

Frailty, Brief screening, Older adults, Chronic disease, Primary care

-

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.