Research Article

Research Article

Drowning Incidents Among Older Adults in Spain (2013-2025): Epidemiological Patterns and Risk Factors

Luis-Miguel Pascual-Gomez1* and Diego García-Saiz2

1Escuela Segoviana de Socorrismo, Segovia Lifesaving School, Spain

2Department of Computing Engineering, Universidad de Cantabria, Spain

Luis Miguel Pascual-Gomez, Escuela Segoviana de Socorrismo, Segovia Lifesaving School, Spain

Received Date:June 06, 2025; Published Date:June 13, 2025

Abstract

Background: This cross-sectional epidemiological study characterises drowning incidents and associated fatalities in Spain between 2013 and

April 2025, with a particular focus on the population aged 65 and older.

Methods: This prospective analysis uses data collected as part of a long-term research initiative that systematically tracks fatal and non-fatal

drowning incidents in Spain. Sources include online media, emergency service reports, and social media. We examined trends in fatalities, victim

demographics, and location-based risks, with a focus on the population aged 65 and above. We identify demographic risk profiles, the most common

causes, high-risk activities, location and seasonality of events, and the dynamics of detection and intervention within this vulnerable age group.

Results: A total of 2,561 victims aged 65 and older were involved in 2,377 drowning incidents, resulting in 1,827 deaths. The data reveal a high

case fatality rate (CFR) in this age group. Males consistently represented a higher proportion of both victims and fatalities. Location type significantly

influenced outcomes, with rivers and seas being particularly lethal environments. Notably, October 2024 saw a spike in deaths due to an unusual

meteorological event (DANA) that resulted in flooding in some regions of West and Southern Spain, accounting for 235 deaths, of which 128 were

aged 65 and older.

Conclusion: Older adults, especially men, constitute a highly vulnerable group, accounting for a significant proportion of incidents and exhibiting

an elevated mortality rate. Factors such as pre-existing medical conditions, accidental falls, and inadequate supervision in the aquatic environment

emerge as crucial. The study also highlights the notable proportion of non-Spanish victims and identifies variations in fatality rates across different

water-related environments. These findings are vital for developing targeted preventive and educational strategies to enhance aquatic safety among

the elderly and diverse populations, particularly in natural water bodies and during adverse weather events. They provide actionable guidance for

public health officials, caregivers, and individuals to improve aquatic safety and prevent drownings among older adults.

Keywords:Drowning; Epidemiology; Elderly Health; Injury Prevention; Aquatic Safety; Spain; Foreign Nationals

List of Abbreviations:ALS: Advanced Life Support; CFR: Case Fatality Rate; CPR: Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation; DANA (Spanish meteorological acronym for “Depresión Aislada en Niveles Altos”, isolated depression at high levels); EMS: Emergency Medical Service; ESS: Escuela Segoviana de Socorrismo (Segovia Lifesaving School); GCS: Glasgow Coma Scale; INE: Instituto Español de Estadística (Spanish Statistical Institute); NCIS: National Coronial Information System (Australia)

Introduction

Drowning is recognised globally as a significant public health issue and is a leading cause of injury-related mortality [1-4]. Worldwide, it accounts for approximately 360,000 deaths annually [2]. Historically, drowning prevention efforts have often concentrated on children and young adults, who represent a large portion of the burden [1,4]. However, understanding the characteristics and risk factors of drowning incidents is crucial for designing effective prevention strategies tailored to specific populations and age groups [5,6]. In recent years, older adults aged 65 years and older have emerged as an increasingly important demographic concerning drowning risk [1,3]. The estimated number of drowning deaths among older adults globally nearly doubled between 1990 and 2017 [1]. In some high-income countries, such as Canada, older adults now have the highest drowning death rate of any age group [1]. This trend highlights the need for a better understanding of drowning among this cohort to develop more effective prevention strategies [3,7].

Several key factors are associated with drowning incidents in older adults, including the location of the drowning, risk factors related to the aquatic environment, personal factors, and underlying medical conditions [1,3,8,9,10]. While drowning can occur in various places, studies have highlighted the significance of specific settings for older adults. For instance, bathing is a notable activity leading to drowning in older adults, with a considerable proportion of bath-related drownings occurring among victims aged 65 and over [5]. Research also indicates that aquatic-specific design features, such as ramps and pool lifts, can help older adults safely participate in water activities. [11,12]. The presence of regulations related to open-water swimming sites has also been associated with lower drowning rates [13]. Pre-existing medical conditions play a substantial role in drowning deaths among older people [3,8,10,14,15,16]. In some cases, a chronic medical condition was known to be present in the majority of older adults who drowned [8,16]. Older adults who drowned commonly had multiple comorbidities [8]. Heart disease is frequently the leading medical condition observed in older adults who drown, often followed by conditions such as dementia, diabetes, physical disability, respiratory disorders, and mental illness [8]. Physical disability and mobility issues can create difficulties with entering and exiting water safely [11,12]. The potential impact of medication use, including polypharmacy, implicated in an increased likelihood of falls, on drowning risk warrants further exploration [17-19].

Given the prevalence of medical conditions like heart disease and stroke in the older adult population [17,20,21], understanding how these conditions contribute to drowning is crucial for prevention efforts [17]. Experts suggest educating healthcare providers about existing diseases that increase drowning risk in older adults [22]. Advice for individuals with pre-existing health conditions may include limiting aquatic activities to areas with lifeguard services or where companions received training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Lifeguard supervision is a commonly identified preventive strategy in itself. [23]. Regarding outcomes, elderly drowning patients are more likely to experience severe consequences compared to younger adults [24]. Studies indicate that older adults aged 65 and over are more likely to experience cardiac arrest at the time of arrival at the emergency department, hypothermia, admission to the intensive care unit, and mortality following a drowning incident than adults aged 18-64 [24]. For example, mortality rates were significantly higher in the elderly group compared to the adult group in one study [24]. Factors such as submersion time, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, and central body temperature upon arrival can also influence prognosis [25-28]. Analysing drowning data using counts, proportions, and rates is essential for understanding the scope of the problem and identifying at-risk groups. While elderly patients constitute a smaller count of total drowning cases in some settings (e.g., approximately 1/10 of cases in one study [24,30]), their higher proportion among fatalities and greater severity of outcomes emphasise their vulnerability [24].

Understanding the unique risk factors and clinical characteristics associated with drowning in older adults is essential for developing targeted and effective prevention strategies and improving the prognosis for victims [3,5,7,31,32]. Spain, with its growing ageing population and extensive coastline and inland waters, provides a relevant setting for studying this problem. A thorough epidemiological characterisation of drowning in this age group is essential for identifying risk patterns, developing specific prevention strategies, and improving response to these incidents. This study aims to characterise the epidemiology of drowning incidents in Spain between 2013 and 2025, focusing on epidemiological aspects relevant to the older population, including the profile of victims (age, sex, and nationality), the circumstances of the incident, causes, associated risk factors, high-risk activities, and intervention effectiveness.

Materials and Methods

Spain does not have a centralised data system that collects information on all deaths reported by a coroner in the country (such as the Australian NCIS, for example). The Spanish Statistical Institute (INE) publishes annual figures on the number of deaths and their causes. However, there is no easy way to obtain qualitative or forensic data on those who die by drowning, as the information is distributed across several very different areas, organisations and administrations (EMS, hospitals, courts, etc.), and personal and medical-related data have strong legal protection. This study utilises data from an extensive, ongoing research project initiated in 2008 by ESS (Escuela Segoviana de Socorrismo). The project has systematically compiled information on drowning incidents in Spain since 2013. Data collection involves setting up predefined Google Alerts for public sources, including traditional and online media outlets, communications from state and regional emergency services and social media.

ESS meticulously integrates information from these sources into a relational database, which is managed entirely by ESS. The database comprehensively includes all available drowning incidents that have occurred in aquatic environments within Spain, recording 35 predefined data points per incident (20 for the incident itself and 15 for each involved victim). ESS experts are responsible for the proper extraction, review, pre-processing, and loading of all data. As of the time of writing this article, the overarching project database comprised a total of 8,777 drowning incidents involving 11,596 victims and resulting in 5,170 fatalities across all age groups and types of incidents.

For this specific article, we extracted a subset of this comprehensive dataset, focusing exclusively on records where the victims were aged 65 years or older. This targeted extraction yielded a specific dataset comprising 2,377 incidents (27.08%) involving 2,561 victims (22.08%) and 1,827 fatalities (35.33%). The analysis conducted was a descriptive prospective study utilising the extracted dataset from January 1, 2013, to the available data as of the end of April 2025. The database includes detailed information on the victim (age, sex, nationality, medical history), the incident (location, time, aquatic environment conditions, activity performed, cause, risk factors, victim’s background), and the response (who detected, first responder, extraction, resuscitation manoeuvres, prognosis). The analysis included both non-fatal and fatal incidents within the elderly group.

It is important to note that data for the years 2021 and 2022 (as the data for these two years was still reviewed at the time of exporting, only the already cleaned data were used) and 2025 (data from January to April) are considered incomplete at the time of analysis. Furthermore, an exceptional meteorological event, the DANA (Isolated Depression at High Levels) of October 2024, which resulted in a total of 235 drowning fatalities, of which 128 were over 65 years old, was identified and considered in context to avoid distorting general annual trends (see Table 1).

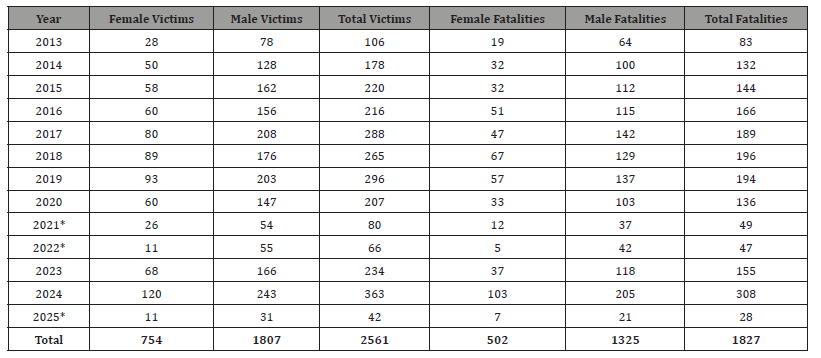

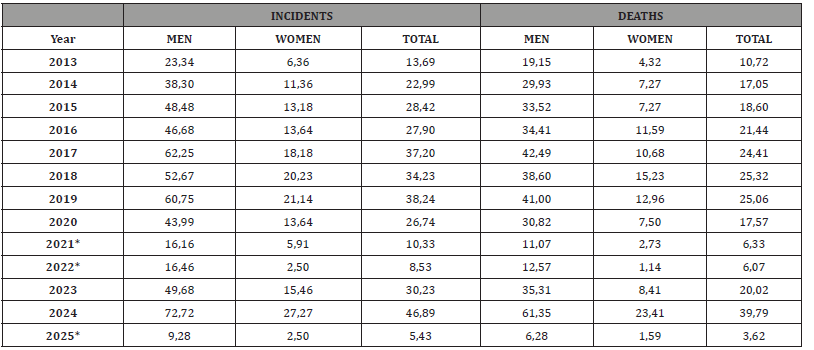

Table 1:Number of Victims and Fatalities by Year of Occurrence and Sex.

Note: Totals for victims and fatalities in this table reflect the specific breakdowns by year and sex available in the source data. * Years with incomplete data.

Results

General Overview of Incidents and Mortality

During the study period (2013-2025), focusing on the extracted dataset of victims aged 65 and over, a total of 2,561 drowning victims were identified in 2,377 incidents. Of these, 1,827 had a fatal outcome, representing an overall fatality rate of 71.34% for this specific age group. Annual incidence has shown variations, with peaks in certain years and a marked influence from the October 2024 DANA event, which alone accounted for 128 fatalities in that year.

Demographic Profile of Victims: Age, Sex, and Nationality

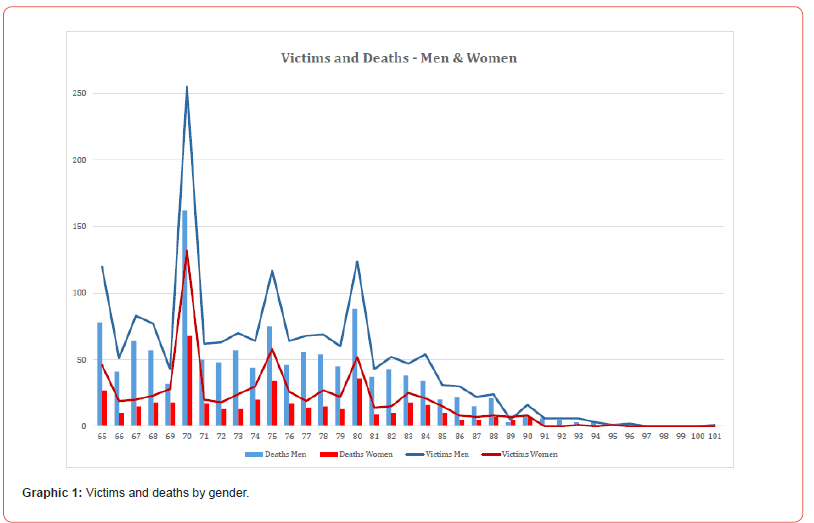

Analysis by sex revealed a marked male predominance within the elderly group. Men constituted 70.56% (1,807) of all victims and 72.52% (1,325) of fatal drownings among those aged 65+. (see Graphic 1)

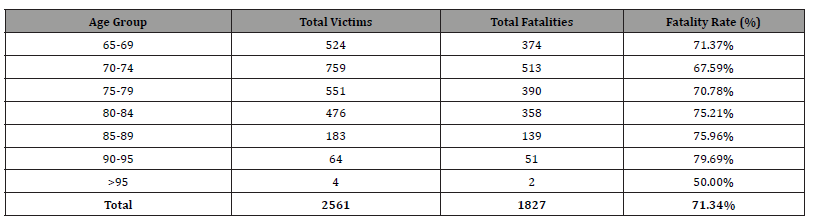

The fatality rate was slightly higher in men (73.33%) compared to women (66.58%). The population aged 65 and older, by definition the focus of this study, represented 22.08% (2,561) of the total victims (11,596) in the broader project database (though this specific study extracted only 65+ victims, this calculation is contextual) and an alarming 35.33% (1,827) of all fatal drownings in the broader project database (5,170). Within the 65+ group itself, the fatality rate is exceptionally high (see Table 1), with an average of 71.34% (79.69% for the 90-95 age range) (see Table 2). Regarding nationality, non-Spanish nationals accounted for 84.34% (2,160) of all drowning victims and 85.05% (1,554) of fatal drownings. The fatality rate among foreign nationals was slightly lower at 68.08% compared to Spanish nationals at 71.94%.

Table 2:Proportion of Fatalities by Victim Age Group (All Ages).

Note: The “Total Victims” column reflects the sum of victims in the 65+ age group (2561) used for this study. The “Total Fatalities” column reflects the sum of fatalities within the age groups presented (1827).

Geographical Distribution and Seasonality

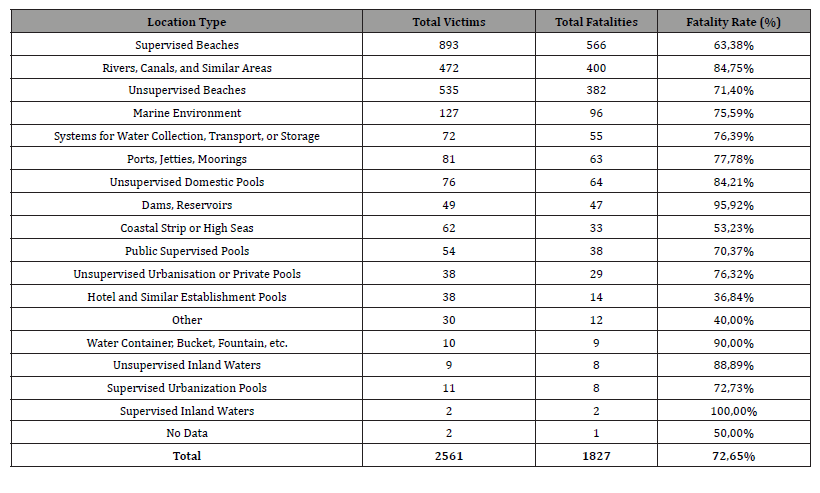

The most frequent locations for incidents were supervised

beaches (893 victims), rivers, canals, and similar areas (472 victims),

and unsupervised beaches (535 victims). The fatality rates

varied significantly by location type (see Table 3).

• Supervised beaches: 63.38% (566 fatal out of 893 total incidents).

• Unsupervised beaches: 71.40% (382 fatal out of 535 total incidents).

• Rivers, canals, and similar areas: 84.75% (400 fatal out of 472

total incidents).

• Marine environments: 75.59% (96 fatal out of 127 total incidents).

• Ports, jetties, and moorings: 77.78% (63 fatal out of 81 total

incidents).

• Dams, Reservoirs: 87.76% (43 fatal out of 49 total incidents).

Insert Table 3 here

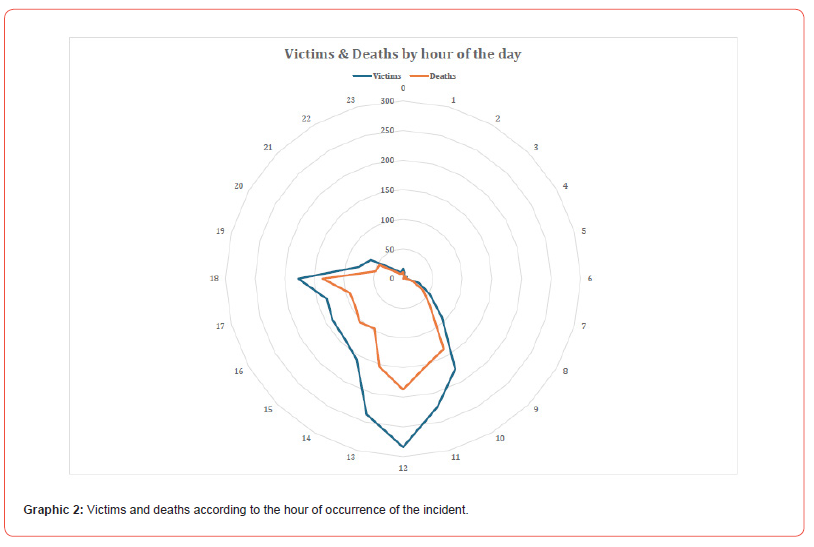

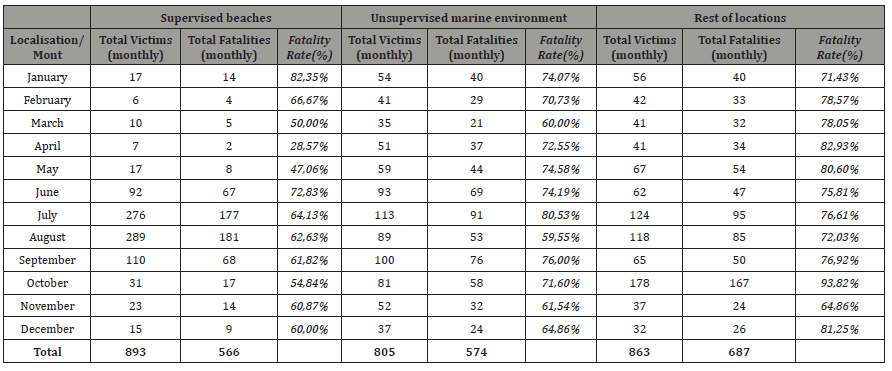

Mid-day hours (approximately between 10:00 and 20:00) also concentrate the majority of incidents. (See Graphic 2). Seasonality is pronounced, with the majority of incidents occurring during the summer months. July (279) and August (289) are consistently the months with the highest number of drownings, followed by September (110).

Table 4 details the monthly distribution of total drowning victims and fatalities among individuals aged 65 and over across three key location categories: Supervised Beaches, Unsupervised Marine Environment, and Rest of Locations. It reveals a pronounced seasonality, with significant peaks in both victims and fatalities during the summer months (July-August) across all environments. The data consistently highlight the lower fatality rates on Supervised Beaches, underscoring the critical role of vigilance. Conversely, the ‘Rest of Locations’ category exhibits the highest overall fatality rates, with a notable spike in October, suggesting particularly severe incidents or specific hazards in these diverse environments (also accounting for the October 2024 DANA event).

Table 3:Number of Victims and Fatalities by Location Type.

Table 4:Monthly Victim and Fatality Counts for Selected Locations.

Causes and Risk Factors

The most frequent causes of incidents identified (excluding the “No data” category, which has the most significant number of records at 1,238, when the leading cause of the incident could not be determined from the available information.) are “Accidental fall or dive” (452; 17.64%) and “Illness heart attack or stroke” (275; 10.73%). The latter is particularly relevant for the elderly population. The victims of October 2024 DANA (128) illustrate the significant impact that extreme meteorological events can have. Victims with dementia or mental illness (38 victims, 30 fatal; fatality rate of 78.94%), physical disability (28 victims, 24 fatal; fatality rate of 85.71%), and heart disease (47 victims, 35 fatal; fatality rate of 74.46%) show elevated mortality rates. These data highlight the need for special considerations for these groups, emphasising the impact of comorbidities and functional status on aquatic safety.

High-Risk Activities

“Recreational swimming” (1,490; 58.18%) is by far the most frequent activity associated with drowning incidents. It is followed by “Activity near water” (653; 25.50%), which often involves accidental falls. “Fishing from beach or rocks” (86; 3.32%) and “Vehicle circulation” (83; 3.25% -including cases from the DANA-) also represent significant risks.

Incident Circumstances and Intervention

More than half of the incidents (60.17%, 1,541 cases) occur in unsupervised areas, underscoring the lack of supervision as a critical risk factor. Even under “Good meteorological or water conditions or Green Flag”, 295 (11.51%) incidents were recorded, suggesting that the perception of safety can be misleading and that intrinsic risk or individual factors persist. The initial detection of the incident is performed mainly by citizens (1,390; 54.27%), followed by on-duty lifeguards (597; 11.59%) and companions, family, or friends (414; 16.16%). Similarly, the first responders are often citizens (1,452; 56.69%) or lifeguards (585; 22.84%). Regarding resuscitation manoeuvres, basic CPR and Advanced Life Support (ALS) by EMS (Emergency Medical Services) were the most frequently performed interventions (787; 30.73%). However, “Body recovery” (739; 28.85%) and the absence of resuscitation (“No Resuscitation” (339; 13.13%) indicate a high number of fatal incidents or delayed detection.

Table 5:Drowning incidents and deaths ratio per million inhabitants.

Drowning incidents and deaths ratio per million inhabitants. Source: Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE) - Figures as of January 1, 2020. Note: Totals for victims and fatalities in this table reflect the specific breakdowns by year and sex available in the source data. * Years with incomplete data.

Discussion

The findings of this study emphasise the elevated and growing concern for drowning in Spain, with a disproportionate burden on the population aged 65 and over, characterised by high morbidity and exceptionally high mortality, underscoring their extreme vulnerability once a drowning incident occurs. The male predominance in drowning incidents is consistent with international literature. However, in the context of advanced age, this may be intertwined with lifestyle, activity patterns, and a higher prevalence of comorbidities. The significant involvement of non-Spanish nationals in drowning incidents, coupled with a slightly higher fatality rate, strongly suggests the need for culturally sensitive and multilingual prevention campaigns. Tourists and immigrants may face challenges and different perceptions of water safety, suggesting vulnerabilities that are possibly related, such as unfamiliarity with local aquatic environments, language barriers in understanding safety warnings, differing perceptions of water safety, or varying safety behaviours.

The varying fatality rates across different aquatic environments, with rivers and similar areas, as well as dams and reservoirs, posing the highest risk, underscore the need for targeted safety measures and awareness campaigns specific to each type of location. The concentration of incidents on beaches and rivers during the summer months, along with the high incidence in unsupervised areas, underscores the importance of public education on risks in these environments and the need for improved supervision. Causes such as accidental falls and, crucially, acute medical events like heart attacks are particularly relevant for the older population, suggesting that acute medical events can precipitate drowning. These findings, coupled with the high presence of “Age, Illness, Mental Illness” as a risk factor and the high fatality rates in victims with a history of dementia, physical disability, or heart disease, demand a comprehensive, multi-factorial preventive approach as the victim’s personal medical history plays a crucial role in the prognosis. Awareness campaigns should not only focus on general aquatic safety but also on the importance of assessing individual risks based on health status and physical capacity.

For older adults, recreational swimming and activities near water (such as walking or fishing) are particularly relevant given their leisure patterns and potential mobility limitations. Leisure activities such as recreational swimming and water-related activities are predominant, suggesting that even seemingly low-risk activities can pose hazards to this vulnerable population. The fact that drowning incidents happen even under good meteorological or “green flag” water conditions suggests that the perception of safety can be misleading and that intrinsic risk or individual factors persist. Ultimately, the prominent role of citizens as first responders underscores the importance of community training in basic life support and CPR. However, the high rate of “Body recovery” and “No Resuscitation” indicates that, in many cases, detection or intervention occurs too late. In light of an ageing population, the study’s results highlight the critical need for proactive urban aquatic planning and the design of water-based activities to prioritise the safety and accessibility of older adults.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of the study of drownings in Spain -and therefore of this study- is the lack of access to forensic data that could delve deeper into the process and causes of the incidents, as well as the lack of follow-up of non-fatal victims, for example, through personal interviews with victims and witnesses and reports from lifeguard and emergency services that could provide crucial data for understanding the genesis and development of drowning and, in the case of older people, the role of pre-existing health conditions.

Other limitations of this study include the potential incompleteness of data for the most recent years (2021, 2022, and 2025), which could affect the representation of annual trends. Notably, the exceptional DANA event of October 2024, which resulted in 128 drowning fatalities, was included in the overall dataset but considered a contextual anomaly to prevent it from skewing general annual trends, thus recognising its unique and significant, though unrepresentative, contribution to the 2024 figures. The presence of “No data” categories in several important variables (causes, medical history, aquatic risk) limits the depth of some analyses. The observed alignment between total victim and fatality counts in many monthly entries within this detailed breakdown also indicates a strong focus on fatal outcomes in the media reporting for these specific categories.

Conclusion

Age is a critical risk factor. Drowning in Spain is a significant

public health issue with a disproportionate impact on the population

aged 65 and over, characterised by high morbidity and exceptionally

high mortality. Older men with pre-existing medical

conditions or disabilities and non-Spanish nationals who engage in

recreational aquatic activities in unsupervised environments, especially

during summer months, constitute the highest risk profiles.

Prevention strategies must be multifaceted, encompassing:

1. Education and Awareness: Targeted campaigns for older

adults and their caregivers about specific risks associated with

age, comorbidities, and the aquatic environment, and culturally

appropriate messaging for non-Spanish populations.

2. Vigilance and Safety: Improvement and expansion of supervision

in beaches and pools and clear, multilingual signage for

unsupervised risk areas.

3. First Aid and CPR: Promotion of community-level training in

basic life support and CPR to improve bystander response.

4. Activity Adaptation: Encouraging the adaptation of aquatic

activities to individual capabilities, with emphasis on supervision

and the use of flotation aids when necessary.

A comprehensive understanding of drowning risk factors is crucial for designing more effective and targeted preventive strategies, thereby alleviating the burden of aquatic incidents across diverse populations, including older people. Our data specifically underscore the necessity for tailored approaches that account for the significant influence of comorbidities and functional status on aquatic safety. These insights translate directly into practical recommendations for public health officials, caregivers, and individuals, enabling them to enhance water safety protocols and actively prevent drownings in older adults.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the use of Gemini 2.5 for the initial treatment of the raw data, based on author-provided outlines and data, and Notebook LM for reference management, initial drafting of the introduction, and table preparation. Additionally, Grammarly AI was used to refine the English language and check grammar. All AI-generated content was reviewed and edited by the authors, who are ultimately responsible for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict of interest.

References

- Masayuki Murayama, Yoichiro Takahashi, Rie Sano, Kaho Watanabe, Keiko Takahashi, et al. (2015) Characterization of five cases of suspected bathtub suicide. Legal Medicine 17(6): 576-578.

- Takahisa Okuda, Zhuo Wang, Sheldon Lapan, David R Fowler (2015) Bathtub drowning: an 11-year retrospective study in the state of Maryland. Forensic Science International 253: 64-70.

- Hideto Suzuki, Akio Shigeta, Tatsushige Fukunaga (2013) Accidental death of elderly persons under the influence of chlorpheniramine. Legal Medicine 15(5):253-255.

- Naofumi Yoshioka, Takashi Chiba, Misa Yamauchi, Taeko Monma, Katuaki Yoshizaki (2003) Forensic consideration of death in the bathtub. Legal Medicine 5 Suppl 1: S375-S381.

- LD Budnick, DA Ross (1985) Bathtub-related drownings in the United States, 1979-81. American Journal of Public Health. 75(6): 630-633.

- (2018) Canadian Drowning Prevention Coalition. Canadian Drowning Prevention Plan.

- Cornall P (2006) Building Regulation, Health And Safety-Drowning Chapter.

- Sharon Elliott, Jane Painter, Suzanne Hudson (2009) Living alone and fall risk factors in community-dwelling middle age and older adults. Journal of Community Health 34(4): 301-310.

- Élvio R Gouveia, José A Maia, Gaston P Beunen, Cameron J Blimkie, Ercília M Fena, et al. (2013) Functional fitness and physical activity of Portuguese community-residing older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity 21(1): 1-19.

- World Health Organization (2014) Global report on drowning: Preventing a leading killer. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Clemens T, Peden AE, Franklin RC (2021) Exploring a Hidden Epidemic Drowning Among Adults Aged 65 Years and Older. Journal of Aging and Health 33(10): 828-837.

- Mahony AL, Peden AE, Franklin RC, Pearn J, Scarr J (2017) Fatal, unintentional drowning in older people: an assessment of the role of preexisting medical conditions. Healthy Aging Research 6(1): 1-8.

- Pearn J, Peden AE, Franklin RC (2019) The influence of alcohol and drugs on drowning among victims of senior years. Safety 5(1): 8.

- Park H, Satoh H, Miki A, Urushihara H, Sawada Y (2015) Medications associated with falls in older people: Systematic review of publications from a recent 5-year period. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 71(12): 1429-1440.

- Imoisili OE, Goodman AB, Thorpe PG, Reagan-Steiner S, Hong Y (2024) Prevalence of stroke-United States, 2011-2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 73(20): 449-455.

- Lee DH, Park JH, Choi SP, Oh JH, Wee JH (2019) Clinical characteristics of elderly drowning patients. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 37(6): 1091-1095.

- Ballesteros MA, López Hoyos M, Muñoz P, Marin MJ, Miñambres E (2009) Prognosis in Drowning Adults. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 53(7): 935-940.

- Peden AE, Franklin RC, Queiroga AC (2017) Epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for the prevention of global unintentional fatal drowning in people aged 50 years and older: a systematic review. Injury Prevention 24(3): 240-247.

- Justine E Leavy, Corie Gray, Malena Della Bona, Nicola D'Orazio, Gemma Crawford (2023) Review of Interventions for Drowning Prevention Among Adults. Journal of Community Health 48(3): 539-556.

- Weimin Zhu, Xiaxia He, Renfei San, Nanjin Chen, Tingfen Han, et al. (2023) Global, regional, and national drowning trends from 1990 to 2021: Results from the 2021 global burden of disease study. Academic Emerg. Med 30(1): 37-48.

- Smith GS, Keyl PM, Hadley JA, Bartley CL, Foss RD, et al. (2001) Drinking and Recreational Boating FatalitiesA Population-Based Case-Control Study. JAMA 286(23): 2974-2980.

- Mitchell RJ, Williamson AM, Olivier J (2010) Estimates of drowning morbidity and mortality adjusted for exposure to risk. Inj. Prev. 16(4): 261-266.

- Peden AE, Franklin RC, Leggat PA (2018) Preventing river drowning deaths: Lessons from coronial recommendations. Health Promot. J. Aust 29(2): 144-152.

- Ahlm K, Saveman B-I, Björnstig U (2013) Drowning deaths in Sweden with emphasis on the presence of alcohol and drugs-A retrospective study, 1992-2009. BMC Public Health 13: 216.

- Lunetta P, Smith GS, Pentilã A, Sajantila A (2004) Unintentional drowning in Finland 1970–2000: A population-based study. Int. J. Epidemiol 33(5): 1053-1063.

- Haakon H Eilertsen, Peer K Lilleng, Bjørn O Mæhle, Inge Morild (2007) Unnatural death in the elderly: A forensic study from western Norway. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 3(1): 23-31.

- Global Burden of Disease 2013 Cause-of-Death Collaborators (2015) Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Lancet 385(9963): 117-171.

- Tyler MD, Richards DB, Reske-Nielsen C, Saghafi O, Morse EA, et al. (2017) The epidemiology of drowning in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 17(1): 413.

- L Rosella, C Bowman, B Pach, S Morgan, T Fitzpatrick, et al. (2016) The development and validation of a meta-tool for quality appraisal of public health evidence: Meta Quality Appraisal Tool (MetaQAT). Public Health 136: 57-65.

- Quan L, Bennett E, Moran K, Bierens JJLM (2012) Use of a consensus-based process to develop international guidelines to decrease recreational open water drowning deaths. Int J Health Promot Educ. 50(3): 135-144.

- Justine E Leavy, Gemma Crawford, Linda Portsmouth, Jonine Jancey, Francene Leaversuch, et al. (2015) Recreational drowning Prevention Interventions for adults, 1990-2012: a review. J Community Health 40(4): 725-735.

- Guay M, D'Amours M, Provencher V (2019) When bathing leads to drowning in older adults. Journal of Safety Research 69: 69-73.